Published online Mar 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i3.101076

Revised: December 9, 2024

Accepted: January 17, 2025

Published online: March 15, 2025

Processing time: 163 Days and 19.4 Hours

Enterocutaneous (EC) fistula incidence has been increasing in China, along with increases in the volume and complexity of surgeries. The conservative treatment strategy has been analyzed to improve the treatment outcomes for patients with EC fistulas and reduce the need for reoperation.

To analyze the clinical data of patients undergoing conservative treatment for EC fistulas and identify the factors that promote self-healing. These findings provide a reference for improving the clinical cure rate of EC fistulas with conservative treatment.

The clinical data of 91 patients with EC fistulas who underwent conservative treatment were collected. The relationships between the cure rate and characteristics such as age, sex, body mass index, albumin level, primary disease, cause of the fistula, location of the fistula, number of fistulas, nature of the fistula, infection status, diagnostic methods, nutritional support methods, somatostatin therapy, growth hormone therapy, and fibrin glue therapy were analyzed.

A comparison of the basic patient characteristics between the two groups revealed statistically significant differences in primary disease (P = 0.044), location of the fistula (P = 0.006), number of fistulas (P = 0.007), and use of adhesive sealing (χ2 = 12.194, P < 0.001) between the uncured and cured groups. The use of fibrin glue was a significant factor associated with a cure for fistulas (odds ratio = 5.459, 95%CI: 1.958-15.219, P = 0.01).

The cure rate of patients with a single EC fistula can be effectively improved via conservative treatment combined with the use of biological fibrin glue to seal the fistula.

Core Tip: Enterocutaneous (EC) fistulas can cause various complications, such as infections, fluid loss, internal homeostasis imbalance, organ dysfunction, malnutrition, and other changes. This study aimed to improve treatment outcomes for patients with EC fistulas and reduce the need for reoperation. The cure rate of patients with a single EC fistula can be effectively improved via conservative treatment combined with the use of biological fibrin glue to seal the fistula.

- Citation: Zhuang ZN, Zhao R, Li YX. Retrospective analysis of factors influencing the self-healing of patients with enterocutaneous fistulas receiving conservative treatment. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(3): 101076

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i3/101076.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i3.101076

An intestinal fistula refers to an abnormal connection between the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and external digestive tract structures, including other organs, body cavities, or the skin[1]. There are two types of intestinal fistulas: Enterocutaneous (EC) fistulas and intestinal fistulas. EC fistulas can cause various complications, such as infections, fluid loss, internal homeostasis imbalance, organ dysfunction, malnutrition, and other changes[1]. The overflow of intestinal fluid, which contains a large number of bacteria, can lead to severe abdominal infections, retroperitoneal infections, and skin/soft tissue infections[2]. Additionally, the digestive enzymes in the intestinal fluid can damage the tissues of the abdominal wall, corrode blood vessels, and cause bleeding. Infection and bleeding can further lead to multiple organ dysfunction, thereby creating a vicious cycle[3].

The treatment of EC fistulas includes conservative therapy and surgical therapy. The early phase of surgical therapy has a high failure rate, with the rate being as high as 80%. This high failure rate is mainly due to the challenging con

Double cannula drainage is an effective method for controlling abdominal infections, reducing postoperative adverse reactions, and improving the success rate of surgery. Patients with EC fistulas often experience water-electrolyte imbalance, internal environment imbalance, and abdominal infections due to the loss of intestinal fluid. Emergency surgery can result in a high-risk and high-recurrence state occurring in the body[7]. Somatostatin can effectively inhibit the activities of various digestive enzymes in the GI tract, reduce the damage caused by digestive enzymes, and inhibit intestinal fluid secretion, thus improving the postoperative cure rate[8]. Proper managements involving fluid replacement, electrolyte supplementation, and enteral/parenteral nutrition can stabilize the body and ensure the success of surgery. In the later stages, the fistula gradually narrows, and the flow of intestinal fluid decreases or even stops. The injection of fibrin glue into the fistula can effectively promote closure[8].

The research population that was selected by our intestinal fistula center included patients with intestinal fistulas caused by surgeries such as GI surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, gynecological surgery, and urological surgery, and their data were subsequently analyzed. For this study, we selected 91 patients with EC fistulas who underwent conservative treatment. We collected, summarized, and analyzed their data and discussed the factors that contribute to conservative curing. All of the data for this study were obtained from a medical center specializing in the treatment of intestinal fistulas in northern China. By analyzing and presenting a conservative treatment strategy for EC fistulas, this study aims to improve the treatment outcomes for patients with EC fistulas and reduce the need for reoperation.

This study collected data from 91 patients who underwent conservative treatment for intestinal fistulas at the Department of GI Surgery of Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital from January 2016 to December 2019. All of the patients were treated for EC fistulas via a three-stage strategy. The study included 62 males (68.13%) and 29 females (31.87%), with an average age of 55.79 ± 15.90 years. The patient data that were used in this study were reviewed and approved by the hospital ethics committee, and patient privacy was protected. All of the case data were carefully collected by the attending physician and rereviewed by two or more specialists. Patients were included in the study based on a diagnosis of EC fistula, which was confirmed via clinical manifestations, laboratory/imaging findings, and intraoperative explorations.

The inclusion criterion for this study was patients who were diagnosed with EC fistulas and who were enrolled in the conservative treatment program. Specifically, these patients were EC fistula patients who were admitted to general wards for conservative treatment with double cannula drainage, without any emergency surgery. The exclusion criteria were patients who were hospitalized for less than 21 days, who died after conservative treatment, or who opted out of the treatment.

The endpoints that were considered in this study included successful self-curing of the EC fistula after conservative treatment or failure of self-curing resulting in surgery.

The EC patients gradually recovered under conservative treatment, which included double-cannula abscess drainage, liquid-electrolyte and/or acid-base balance, and enteral and/or parenteral nutritional support. Additional methods, such as somatostatin therapy, growth hormone therapy, and glue plugging, were used to achieve self-curing of the intestinal fistula. The special therapies including the uses of somatostatin, growth hormone, and fibrin glue plugging were found to be more effective in achieving a cure for EC fistulas.

Some EC fistula patients were in an emergency state upon admission. Debridement of the abdominal wound was performed for patients who required the insertion of a double cannula tube. This procedure was used to decrease abdominal infections, rectify septic shock, and correct disturbances in acid-base and/or water-electrolyte balance. The goal of emergency therapy was to stabilize patients, after which conservative treatment could be administered for 1-2 months. During the conservative treatment stage, it was necessary to evaluate the number and nature of intestinal fistulas, analyze the degree of infection, and monitor organ function. Some EC patients are able to experience self-healing as their bodies recover. If conservative treatment was unsuccessful, the patients were transferred to a surgical treatment program.

All of the data were subjected to statistical analysis using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Co. Ltd.) and R 4.0.5 (Lucent Technologies, Inc.). Normal distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, whereas homogeneity of variance was assessed using the Levene test. In this study, the quantitative data followed a normal distribution and are presented as the mean and SD. Intergroup comparisons were performed using two independent sample t-tests. Qualitative data are described as the number of cases (%), and intergroup comparisons were conducted using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact probability method. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine the influencing factors of a conservative treatment cure, and the model was visualized using forest plots. The logistic regression model included a product term to determine multiplicative interactions. Interactions were considered absent when the 95%CI of relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI), attributable proportion due to interaction (AP), odds ratio (OR), and synergy index (S) included 0 and 1. The predictive performance of the model was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, as well as analyses of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and the Jordan index. Logistic regression and forest plotting were implemented using the RMS and forest plot packages. The significance level was set at α = 0.050.

A total of 91 patients were included in this study, with 62 males (68.13%) and 29 females (31.87%). Among them, 55 patients (60.44%) achieved a cure after conservative treatment, whereas 36 patients (39.56%) did not achieve a cure. The average patient age was 55.79 ± 15.90 years. The patient characteristics included age, sex, body mass index, albumin levels, primary disease, cause and location of the fistula, number and nature of the fistulas, infection status, diagnostic methods, nutritional support methods, somatostatin therapy, growth hormone therapy, and fibrin glue therapy (Table 1).

| Category | Uncured group (n = 36) | Cured group (n = 55) | χ2 | P value |

| Age (years) | 54.64 ± 17.90 | 56.55 ± 14.56 | 0.557 | 0.579 |

| Gender | 2.552 | 0.110 | ||

| Male | 28 (77.78) | 34 (61.82) | ||

| Female | 8 (22.22) | 21 (38.18) | ||

| BMI (kg/m²) | 20.57 ± 3.76 | 21.86 ± 3.72 | 1.610 | 0.111 |

| Albumin level (g/L) | 33.95 ± 5.68 | 35.12 ± 5.59 | 0.967 | 0.336 |

| Primary disease | 0.044 | |||

| Abdominal wall mass | 1 (2.78) | 2 (3.64) | ||

| Abdominal external hernia | 1 (2.78) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Abdominal trauma | 2 (5.56) | 7 (12.73) | ||

| Gastroduodenal disease | 3 (8.33) | 8 (14.55) | ||

| Intestinal disease | 9 (25.00) | 4 (7.27) | ||

| Appendix disease | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.82) | ||

| Colorectum disease | 10 (27.78) | 25 (45.45) | ||

| Hepatobiliary/pancreatic disease | 4 (11.11) | 6 (10.91) | ||

| Acute abdominal disease | 2 (5.56) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Vascular disease | 1 (2.78) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Urological disease | 1 (2.78) | 2 (3.64) | ||

| Gynecological disease | 2 (5.56) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Fistula reason | 0.055 | |||

| Surgery | 33 (91.67) | 52 (94.55) | ||

| Trauma | 0 (0.00) | 3 (5.45) | ||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 2 (5.56) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Radio-/chemotherapy | 1 (2.78) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Fistula location | 0.006 | |||

| Esophagus/stomach | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.82) | ||

| Duodenum | 2 (5.56) | 11 (20.00) | ||

| Bile bowel/pancreatic bowel | 1 (2.78) | 1 (1.82) | ||

| Anastomosis fistula | ||||

| Intestinal fistula | 20 (55.56) | 14 (25.45) | ||

| Colorectum fistula | 13 (36.11) | 21 (38.18) | ||

| Complex fistula | 0 (0.00) | 7 (12.73) | ||

| Fistula number | 7.354 | 0.007 | ||

| Single fistula | 20 (55.56) | 45 (81.82) | ||

| Multiple fistula | 16 (44.44) | 10 (18.18) | ||

| Fistula nature | 0.277 | |||

| Tubular fistula | 33 (91.67) | 48 (87.27) | ||

| Labral fistula | 2 (5.56) | 7 (12.73) | ||

| Internal fistula | 1 (2.78) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Infection status | 0.617 | 0.432 | ||

| None | 14 (28.89) | 17 (30.91) | ||

| Yes | 22 (61.11) | 38 (69.09) | ||

| Diagnostic methods | 0.249 | |||

| Drainage fluid observation | 16 (44.44) | 31 (56.36) | ||

| Abdominal wound observation | 12 (33.33) | 13 (23.64) | ||

| DFO + AWO | 6 (16.67) | 11 (20.00) | ||

| Imaging diagnosis | 2 (5.56) | 0 (0.000 | ||

| Nutrition feeding | 1.043 | 0.307 | ||

| None | 1 (2.78) | 6 (10.91) | ||

| Yes | 35 (97.22) | 49 (89.09) | ||

| Somatostatin | 0.009 | 0.925 | ||

| None | 20 (55.56) | 30 (54.55) | ||

| Yes | 16 (44.44) | 25 (45.45) | ||

| Growth hormone | 3.376 | 0.066 | ||

| None | 25 (69.44) | 47 (85.45) | ||

| Yes | 11 (30.56) | 8 (14.55) | ||

| Fibrin glue | 12.194 | < 0.001 | ||

| None | 29 (80.56) | 24 (43.64) | ||

| Yes | 7 (19.44) | 31 (56.36) |

A comparison of the basic patient characteristics between the two groups revealed statistically significant differences in primary disease (P = 0.044), location of the fistula (P = 0.006), number of fistulas (P = 0.007), and use of adhesive sealing

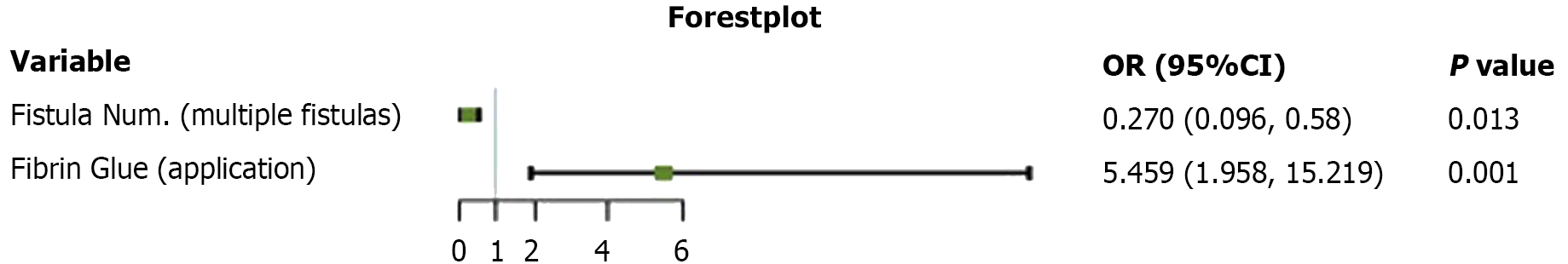

Univariate regression analysis was used to identify the independent influencing factors for the cure of fistulas, including primary disease, location of the fistula, number of fistulas, and application of fibrin glue. The results revealed that the presence of multiple fistulas (OR = 0.270, 95%CI: 0.096-0.758, P = 0.013; Table 2 and Figure 1) and the use of fibrin glue (OR = 5.459, 95%CI: 1.958-15.219, P = 0.01; Table 2 and Figure 1) were significant factors associated with a cure for fistulas.

| b | Sb | χ2 | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Constant | 0.199 | 0.319 | 0.389 | 0.533 | |

| Fistula number (multiple) | -1.309 | 0.526 | 6.179 | 0.270 (0.096, 0.758) | 0.013 |

| Fibrin glue application | 1.697 | 0.523 | 10.528 | 5.459 (1.958, 15.219) | 0.001 |

Binary regression analysis was performed to assess the presence of multiplicative interactions between fistula number and fibrin glue application. The results revealed no significant interaction (P = 0.813; Table 3).

| Category | b | Sb | χ2 | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Constant | 0.223 | 0.335 | 0.443 | 1.250 | 0.506 |

| Fistula number (multiple) | -1.402 | 0.663 | 4.472 | 0.246 (0.067, 0.903) | 0.034 |

| Fibrin glue application | 1.609 | 0.634 | 6.436 | 5.000 (1.142, 17.338) | 0.011 |

| Fistula number + fibrin glue application | 0.262 | 1.109 | 0.056 | 1.300 (0.148, 11.422) | 0.813 |

The additive interaction between fistula number and fibrin glue application was evaluated via the RERI, AP, and S parameters. There was no additive interaction observed between the number of fistulas and the application of fibrin glue, as indicated by the results of RERI = -2.646 (RERI 95%CI: -8.858 to 3.567), AP = -1.653 (AP 95%CI: -6.614 to 3.306), and S = 0.185 (S 95%CI: 0.003-11.120).

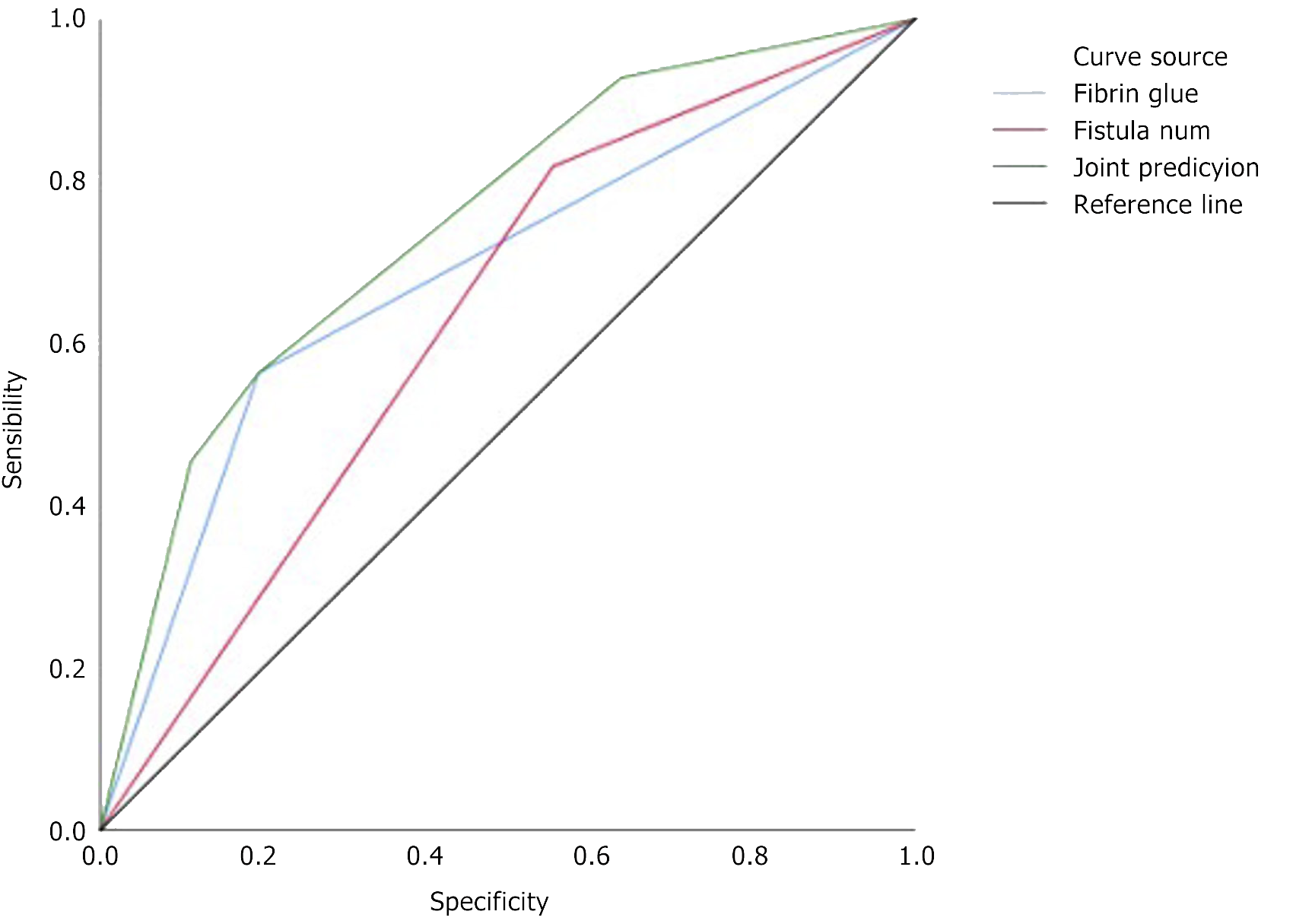

A comparison of the predictive effects of the number of fistulas, the application of fibrin glue, and the combination of the number of fistulas and fibrin glue application was performed. The results revealed a statistically significant difference in the predictive performance between the combination of the number of fistulas and fibrin glue application and any single indicator (P < 0.050; specific predictive performance results in Table 4; area under the curves of different indicators' predictions in Figure 2). The combined model of the number of fistulas and fibrin glue application had a sensitivity value of 56.36% and a specificity value of 80.56% (Table 5).

| Constant | Fistula number | Fibrin glue application | ||

| z | P value | z | P value | |

| Fistula number + fibrin glue application | -2.242 | 0.025 | -2.517 | 0.012 |

| Category | Therapeutic prediction of fistula number and fibrin glue application | |

| Uncured (n = 53) | Cured (n = 38) | |

| Outcome of conservative treatment | ||

| Uncured (n = 36) | 29 | 7 |

| Cured (n = 55) | 24 | 31 |

| Sensitivity | 56.36 | |

| Specificity | 80.56 | |

| Positive predictive value | 81.58 | |

| Negative predictive value | 54.72 | |

| Youden index | 36.92 | |

| AUC | 0.747 (0.644, 0.850) | |

The incidence of EC fistulas has been increasing in China, along with increases in the volume and complexity of surgeries. The incidence rate of EC fistulas in general surgery is approximately 1.88%[9]. National intestinal fistula treatment (NIFT) centers have been established in many countries or regions to improve the cure rate of EC fistulas. Patients with EC fistulas are recommended to be transferred to NIFT centers for specialized treatment[10]. Furthermore, the worldwide mortality rate for intestinal fistulas is nearly 10%[11], with a mortality rate of 3.9% being observed in China's NIFT centers[12].

The stable stage of EC fistulas is a critical time for patients, as self-healing is possible with effective fistula drainage and tissue recovery[13]. In our NIFT center, we use a double cannula tube for the drainage of digestive fluid from the intestinal fistula. This tube is specifically designed for EC fistulas and can be continuously rinsed with water and continuously suctioned with negative pressure; moreover, this tube prevents clogging via multiple side holes. This therapy was used in 91 stable-stage EC fistula patients, with a cure and discharge rate of 60.44% being demonstrated. Patients who did not achieve self-healing via conservative treatment were transferred for definitive surgery of the EC fistula.

We analyzed the basic characteristics of EC fistula patients under conservative treatment. The degree of self-healing of fistulas was significantly related to the primary disease, fistula location, fistula number, and fibrin glue application. The location of EC fistulas is determined by the operation area related to different primary diseases. The recurrence of anastomotic tumors is a significant factor leading to the failure of EC fistulas to self-heal. High-level fistulas are characterized by high flow leakage of digestive fluid but a lower degree of bacterial infection. These types of fistulas can undergo easier and faster self-healing with adequate drainage and nutritional supplementation. In contrast, low-level fistulas have low flow leakage and a higher degree of bacterial infections, which results in greater difficulties in self-healing or higher recurrence rates. The accurate assessment of the number of fistulas is crucial for determining the success or failure of self-healing in EC fistula patients under conservative treatment. Although most patients possess only one fistula, some may have multiple fistula sinus tracts, with a single outer opening but multiple internal openings connected by a common sinus tract. Thus, fistula angiography is essential for determining the numbers of EC fistulas and sinus tracts.

In the later stages of conservative treatment for EC fistulas, fibrin glue is used to close the sinus tracts. Some patients are unable to achieve complete closure of the sinus tract after the withdrawal of the double cannula tube, thus resulting in a small amount of tissue fluid flowing out. However, the use of fibrin glue (which is a biological protein glue) has demonstrated positive results in achieving self-healing. Each of the independent influencing factors, including primary disease, fistula location, fistula number, and fibrin glue application, was shown to be significant in relation to self-healing; however, no multiplicative interactions or additive interactions were observed between these factors.

This study aimed to evaluate the predictive effects of a two-factor combination of fistula number and fibrin glue application compared with the single factors of fistula number or fibrin glue application. The results showed that the combination of a single fistula and fibrin glue application improved the predictive performance and was more likely to achieve the goal of self-curing. However, the probability of failure significantly increased for patients with multiple fistulas under conservative treatment (whether combined with or without fibrin glue application). The combination model, which analyzed the number of fistulas and fibrin glue application, had a sensitivity of 56.36% and a specificity of 80.56%. Therefore, the accurate evaluation of the number of EC fistulas using fistula imaging technology is necessary. For patients with a single EC fistula, fibrin glue application is recommended to improve the self-curing rate in the last stage of conservative treatment when the sinus tract is contracted and the drainage fluid becomes clear.

We have summarized the strategies for cured patients in the stable stage of EC fistula. First, nutritional support therapy is recommended, as it not only increases weight and improves nutrition in patients with EC fistulas but also enhances tissue healing ability[14]. Second, the combination of somatostatin, growth hormone, and fibrin glue therapies is suggested. For patients with high-flowing fistulas, somatostatin therapy can reduce GI fluid secretion in the early stage, growth hormone therapy can significantly improve the body's self-healing ability in the middle stage, and fibrin glue therapy can improve the self-curing rate of the fistula in the later stage. Third, the accurate assessment of fistulas is crucial. Fistula angiography, abdominal computed tomography scan post angiography, and complete colonoscopy angiography are used in our center. C-reactive protein is also used to evaluate changes in EC fistulas, as it has been shown to be a useful parameter for predicting potential recurrence in EC fistulas[15]. Fourth, the use of double-tube drainage technology, which involves continuous drip irrigation and continuous negative pressure suction, is recom

Intestinal fistula is a complication that can occur after surgery. Moreover, digestive tract tumor surgery was the source of the intestinal fistula that was investigated in this study. Due to the fact that intestinal fistula is a rare complication, the patient population with respect to this disorder is not large. Therefore, our research still requires more cases concerning the confidence interval of the cure rate with a single EC fistula patient.

EC fistula can cause various complications, such as infections, fluid loss, internal homeostasis imbalance, organ dysfunction, malnutrition, and other changes. The cure rate of patients with a single EC fistula can be effectively improved through conservative treatment combined with the use of biological fibrin glue to seal the fistula.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. We are grateful for the contributions from Peng Chen, who collected the clinical data and analyzed the biostatistics. Peng Chen, Department of Biostatistics, Zhongshan Kangfang Biopharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Beijing, 100022, China.

| 1. | Dodiyi-manuel A, Wichendu PN. Current concepts in the management of enterocutaneous fistula. Int Surg J. 2018;5:1981. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Tuma F, Crespi Z, Wolff CJ, Daniel DT, Nassar AK. Enterocutaneous Fistula: A Simplified Clinical Approach. Cureus. 2020;12:e7789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bhama AR. Evaluation and Management of Enterocutaneous Fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:906-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Malangoni MA. Evaluation and management of tertiary peritonitis. Am Surg. 2000;66:157-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fan Y, Ren J, Wu X, Gu G, Wang G, Zhao K, Zhao Y, Li J. [Risk factors of surgical site infection in definitive surgery of intestinal fistulas]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015;18:646-650. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Pironi L, Arends J, Baxter J, Bozzetti F, Peláez RB, Cuerda C, Forbes A, Gabe S, Gillanders L, Holst M, Jeppesen PB, Joly F, Kelly D, Klek S, Irtun Ø, Olde Damink SW, Panisic M, Rasmussen HH, Staun M, Szczepanek K, Van Gossum A, Wanten G, Schneider SM, Shaffer J; Home Artificial Nutrition & Chronic Intestinal Failure; Acute Intestinal Failure Special Interest Groups of ESPEN. ESPEN endorsed recommendations. Definition and classification of intestinal failure in adults. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:171-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tirpude B, Borkar MM, Lokhande NN. Study of negative pressure wound therapy in management of abdominal wound dehiscence. Int Surg J. 2020;7:2195. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Gribovskaja-Rupp I, Melton GB. Enterocutaneous Fistula: Proven Strategies and Updates. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016;29:130-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tang QQ, Hong ZW, Ren HJ, Wu L, Wang GF, Gu GS, Chen J, Zheng T, Wu XW, Ren JA, Li JS. Nutritional Management of Patients With Enterocutaneous Fistulas: Practice and Progression. Front Nutr. 2020;7:564379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lundy JB, Fischer JE. Historical perspectives in the care of patients with enterocutaneous fistula. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010;23:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hollington P, Mawdsley J, Lim W, Gabe SM, Forbes A, Windsor AJ. An 11-year experience of enterocutaneous fistula. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1646-1651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zheng T, Xie HH, Wu XW, Chi Q, Wang F, Yang ZH, Chen CW, Mai W, Luo SM, Song XF, Yang SM, Zhou W, Liu HY, Xu XJ, Zhou Z, Liu CY, Ding LA, Xie K, Han G, Liu HB, Wang JZ, Wang SC, Wang PG, Wang GF, Gu GS, Ren JA. [Investigation of treatment and analysis of prognostic risk on enterocutaneous fistula in China: a multicenter prospective study]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2019;22:1041-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Visschers RG, Olde Damink SW, Winkens B, Soeters PB, van Gemert WG. Treatment strategies in 135 consecutive patients with enterocutaneous fistulas. World J Surg. 2008;32:445-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rizka H, Diyah EA. Route delivery of nutrition in patients with enterocutaneous fistula. Med J Malaysia. 2023;78:541-546. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Martinez JL, Luque-de-León E, Ferat-Osorio E, Estrada-Castellanos A. Predictive value of preoperative serum C-reactive protein for recurrence after definitive surgical repair of enterocutaneous fistula. Am J Surg. 2017;213:105-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rahbour G, Siddiqui MR, Ullah MR, Gabe SM, Warusavitarne J, Vaizey CJ. A meta-analysis of outcomes following use of somatostatin and its analogues for the management of enterocutaneous fistulas. Ann Surg. 2012;256:946-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Banasiewicz T, Borejsza-Wysocki M, Meissner W, Malinger S, Szmeja J, Kościński T, Ratajczak A, Drews M. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy in patients with large postoperative wounds complicated by multiple fistulas. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2011;6:155-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cro C, George KJ, Donnelly J, Irwin ST, Gardiner KR. Vacuum assisted closure system in the management of enterocutaneous fistulae. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:364-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Heimroth J, Chen E, Sutton E. Management Approaches for Enterocutaneous Fistulas. Am Surg. 2018;84:326-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |