Published online Jan 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i1.100210

Revised: October 17, 2024

Accepted: November 7, 2024

Published online: January 15, 2025

Processing time: 124 Days and 15.8 Hours

The liver is the most common site of digestive system tumor metastasis, but not all liver metastases can be traced back to the primary lesions. Although it is unusual, syphilis can impact the liver, manifesting as syphilitic hepatitis with inflammatory nodules, which might be misdiagnosed as metastasis.

This case report involves a 46-year-old female who developed right upper abdominal pain and intermittent low fever that persisted for more than three months. No definitive diagnosis of a tumor had been made in the past decades, but signs of multiple liver metastases were recognized after a computed tomo

Clinicians must be aware of the possibility that syphilis can cause hepatic inflammatory masses, especially when liver metastasis is suspected without evidence of primary lesions. A definitive diagnosis should be established in conjunction with a review of the patient’s medical history for accurate therapeutic intervention.

Core Tip: The liver is the most common metastasis site of digestive system tumor, while not all liver metastases could be traced back to the primary lesions. Syphilis is unusual and impacts the liver manifesting syphilitic hepatitis with inflammatory nodules, which might be misdiagnosed as metastasis. We presented a case showing that when multiple hepatic nodules with primary lesions are confronted, focusing on infectious or self-immune diseases based on the patient’s history might help to answer the final question.

- Citation: Wang YJ, Liu ZC, Wang J, Yang YM. Multiple liver metastases of unknown origin: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(1): 100210

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i1/100210.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i1.100210

The liver is the most common metastasis site of digestive system tumors, with malignant colorectal tumors accounting for approximately 70% of metastatic lesions[1]. Incidental identification of single or multiple solid liver lesions is not uncommon in general surgery practice, and it is important to locate the primary tumor or prevent the recurrence of previously treated lesions[2]. However, not all liver metastases can be traced back to the primary lesions. It is essential to exclude inflammatory lesions caused by viruses, bacteria, and special pathogens. Caused by the Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete has reemerged as a significant public health concern[3]. If untreated, it progresses through various stages of infection. Several weeks to months following infection, a subset of patients developed secondary syphilis, which is characterized by a distinctive rash affecting the palms and soles, lymphadenopathy, and systemic symptoms[4]. Syphilis can impact the liver during the secondary stage as syphilitic hepatitis and during the tertiary stage as gumma. The diagnosis of syphilitic hepatitis relies on the presence of abnormal liver tests in conjunction with other indications of systemic syphilis, particularly the characteristic rash[3]. Herein, we present a case of syphilis that manifested as a hepatic mass, which was initially suspected to be a malignant tumor, given the absence of a primary lesion.

The patient’s main complaints were right upper abdominal pain and intermittent low fever persisting for more than three months.

Three months earlier, a 46-year-old female experienced right upper abdominal pain without any obvious cause. It was occasionally accompanied by a slight increase in body temperature, but there were no symptoms of nausea, vomiting, jaundice, palpitation, chest tightness, or changes in bowel habits.

No definitive diagnosis of the tumor had been made in past decades. The patient denied any previous history of infection.

The patient’s family had no history of tumors.

After admission, the patient’s blood pressure was 121 mmHg/75 mmHg, heart rate was 85 beats per minute, and body temperature was 36.8 °C. Tests for abdominal tenderness, rebounding pain, muscle tension, and acute peritonitis were negative. No enlarged lymph nodes were found during the physical examination.

Blood tests revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin: 105 g/L) and an increased neutrophil percentage (82.4%) without an elevated leucocyte count. Total bilirubin was slightly elevated (20.6 μmol/L) according to the results of the biochemical analyses. Coagulation and thyroid function tests were normal. Serum tumor marker levels, including alpha-fetoprotein, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and carcinoembryonic antigen levels, were also within normal ranges. Infectious screening revealed syphilis antibody positivity, yet results of the rapid plasma reagin test were negative. The relative markers of the hepatitis virus were negative. Infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 was also excluded via polymerase chain reaction.

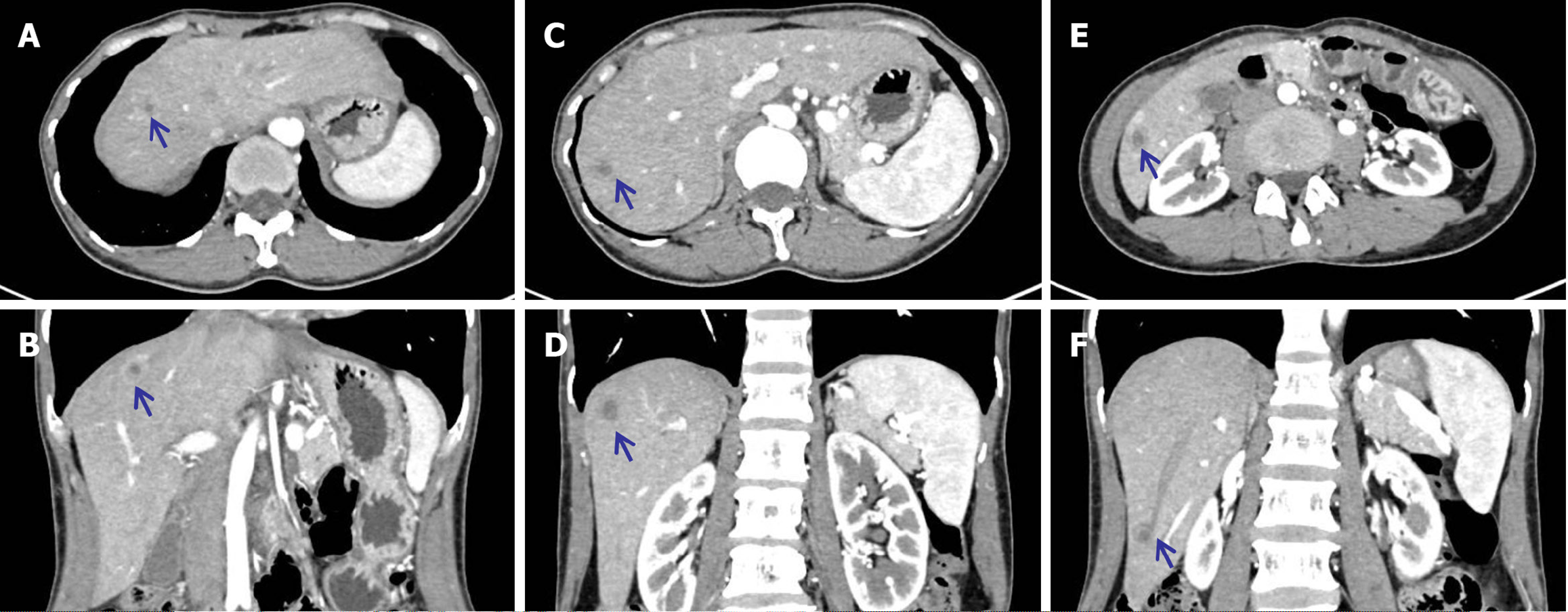

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple potential liver metastases (Figure 1, bull’s eye sign) without certain primary lesions. Due to financial constraints, the patient refused further positron emission tomography/CT scans. Unfortunately, gastrointestinal endoscopy had also been neglected.

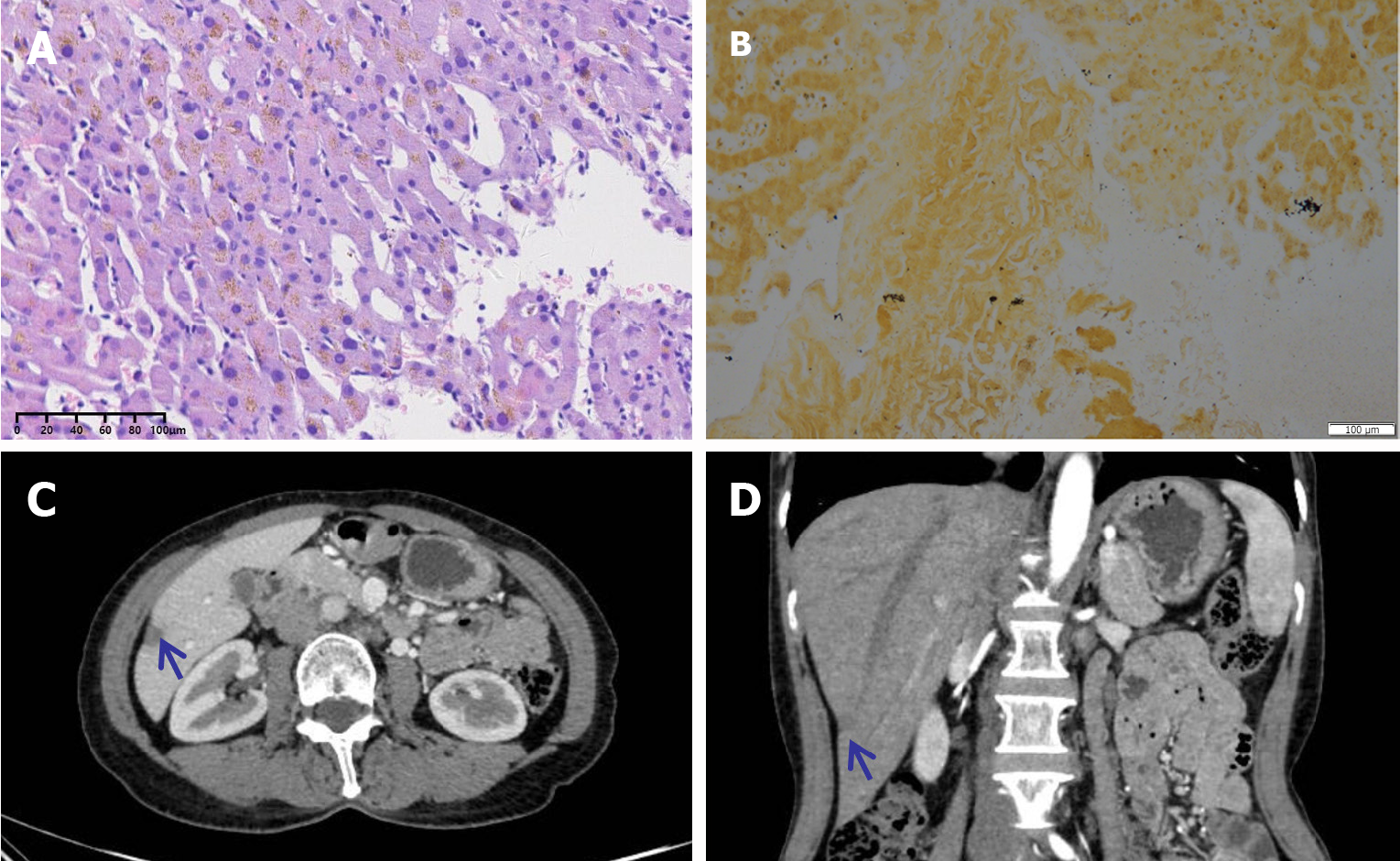

To inform a definite diagnosis, a percutaneous biopsy of the liver was performed, and radiofrequency ablation was completed incidentally. However, the final pathology was not consistent with the preoperative diagnosis. The results revealed fibrinoid necrosis and eosinophilic infiltration without any evidence of cancerous lesions. Recognizing the history of syphilis, hematoxylin-eosin and silver-impregnation staining were performed to confirm the diagnosis of the lesion, and Treponema pallidum was detected (Figure 2A and B).

Penicillin G was subsequently used to control the progression of the hepatic nodules.

A few months later, some small nodules disappeared, and medium nodules were partially reduced or controlled (Figure 2C and D, compared with the pre-treatment results shown in Figure 1E and F).

When confronting multiple liver nodules, especially the typical bull’s eye suggested by contrast-enhanced CT, we usually prefer to consider the diagnosis of liver metastases subconsciously. However, doing so may result in unforeseen complications due to a lack of evidence of a primary tumor. Currently, it is vital to review the patient’s history of infectious diseases, including those caused by bacteria, viruses, parasites, and other pathogens, such as Treponema pallidum. With respect to etiological treatment, multiple liver nodules can be effectively controlled or cured. We reviewed previously reported cases involving multiple hepatic nodules of unknown origin caused by Treponema pallidum. In the literature, 12 cases involving five female patients and seven male patients have been reported. The characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 1. Their average age was 50 years, and the primary symptom was right upper quadrant abdominal pain. The majority of syphilis patients are in stage III and are diagnosed with mucosal damage and gumma. It was evident that male patients tended to carry human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), especially those with a history of sex with men. For treatment, penicillin G was the main therapeutic regimen, and doxycycline was also used. Common outcomes of interest were a reduction in or disappearance of liver nodules and recovery of liver function.

| Ref. | Country | Gender | Age | Primary symptoms | Radiologic or ultrasonic findings | Stage of syphilis | HIV infection | Treatment | Outcome |

| Maincent et al[5], 1997 | France | Female | 56 | Right upper quadrant abdominal pain | Several low-density nodules with no contrast uptake | III | No | Penicillin G (daily for five days and weekly for six weeks) | The abdominal pain subsided, and the liver nodules disappeared |

| Peeters et al[13], 2005 | / | Female | 47 | Vision problems, pain in the right hypochondrium, one enlarged submandibular lymph node | Two hepatic lesions | III | No | Doxycyclin | The sedimentation rate and liver tests normalized, and the hepatic lesions disappeared. However, vision problems remained |

| Mahto et al[6], 2006 | United Kingdom | Male | 44 | Fever, severe persistent upper abdominal pain, weight loss, and a desquamating rash on the palms and soles | Mildly enlarged liver with multiple ill-defined hypoechoic lesions | II | Yes | Doxycycline twice daily for a month | Repeat CT at one month showed that the largest mass decreased in size, and at two months, there was near-complete resolution of the liver masses |

| Shim[7], 2010 | South Korea | Female | 65 | Intermittent abdominal pain and distension | Ascites and two hepatic nodules with peripheral enhancement | III | No | In the beginning, platinumbased combination chemotherapy for six months; after recurrence, penicillin was used | Complete response after six cycles of chemotherapy but recurrence after nine months; liver nodules disappeared followed by penicillin application |

| Hagen et al[3], 2014 | United States | Male | 51 | Follow-up with liver lesions during chemotherapy for Burkitt lymphoma | Two liver lesions on PET | I | Yes | Penicillin G for 2-3 weeks | Resolution of liver test abnormalities and 50% reduction of the liver masses size |

| Male | 53 | Right upper quadrant abdominal pain and weight loss | Multiple enhancing lesions in the liver and spleen, up to 5.7 cm | I | Yes | Liver tests resolved, but follow-up imaging was not performed | |||

| Male | 47 | Fatigue, left lower chest wall pain, fever, chills, intermittent diarrhea, and nausea | Over 50 enhancing lesions in the liver, the largest measuring 2.6 cm | I | Yes | The liver test abnormalities resolved, and virtually complete resolution of the hepatic lesions was achieved | |||

| Gaslightwala et al[11], 2014 | United States | Male | 59 | Persistent fevers, chills, night sweats, and weight loss | Multiple intensely hypermetabolic hepatic lesions on PET/CT | III | No | Penicillin G | None |

| Desilets et al[14], 2019 | Canada | Male | 54 | General deterioration, posterior rib pain, progressive weight loss | PET-scan showed multiple hypermetabolic liver nodules | II | Yes | Penicillin G | Complete interval resolution of hypermetabolic osteomedullary and liver lesions |

| Al Dallal et al[15], 2021 | United States | Female | 36 | Unresponsive with convulsions of all extremities and fever | Multiple hypoenhancing lesions | III | No | Penicillin G for only four days due to patient refusal | Liver function improved, but follow-up imaging was not performed |

| Smith et al[16], 2022 | Australia | Male | 39 | Right upper quadrant and several weeks of fluctuating tenesmus and diarrhea | Short segmental, irregular rectal wall thickening, bilateral mesorectal lymphadenopathy, and multiple hypoattenuating liver lesions | III | Yes | Penicillin G | Significant reduction in the size of a dominant lesion in the right anterior liver section, with no other appreciable lesions |

| Otsuka et al[8], 2023 | Japan | Female | 50 | Low-grade fever and nausea | Three nodules in the S3, S4, and S5 of the liver with round ring enhancement at the portal phase | III | No | Sulbactam sodium and ampicillin sodium | Marked downsizing of liver nodules |

In 1997, Maincent et al[5] reported the first case in which a 56-year-old female presented with right upper quadrant abdominal pain and several low-density liver nodules with no primary origin. Based on the patient’s history of syphilis, serum tests, and pathological evidence from biopsy, hepatic syphilis gumma was diagnosed. The patient was prescribed penicillin G daily for five days and then weekly for six weeks. As a result, not only did her abdominal pain subside but also her liver nodules disappeared. In 2006, Mahto et al[6] reported a case involving a male patient with syphilis who was coinfected with HIV. However, the diagnostic process is not always straightforward. In 2010, Shim[7] described a patient who was initially diagnosed with primary peritoneal serous carcinoma and achieved complete remission following six cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy. Two hepatic nodules subsequently developed during the follow-up period and were originally labeled hepatic metastases. Nevertheless, the pathological examination of resected hepatic nodules did not support the initial diagnosis, underscoring the importance of considering tertiary syphilis in the differential diagnosis of space-occupying lesions, even in the presence of a preexisting cancer diagnosis. Otsuka et al[8] reported a similar case in 2023, adding that syphilitic hepatitis was difficult to identify, especially because it manifested as multiple hepatic nodules with a bull’s eye sign. In terms of radiological features, the hepatic nodules caused by syphilitic hepatitis are similar to those caused by metastatic tumors. Consequently, the special abscesses and tertiary hepatic syphilis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of metastatic tumors.

The manifestations of syphilis, including intermittent low-grade fever, abdominal pain, headache, weight loss, sore throat, arthralgia, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and uveitis, are always non-specific[9,10]. The tertiary stage of syphilis occurs in approximately one-third of untreated patients. Whereas any organ can be affected, the most common manifestations of tertiary disease include gummatous lesions, cardiovascular syphilis, and neurosyphilis[4]. Syphilis can impact the liver during both the secondary and the tertiary stages of the disease. Secondary hepatic syphilis typically develops within a few weeks to a few months following the appearance of the primary chancre[7,11]. Localized gummas may form in the liver during the tertiary stage, typically arising 1 to 10 years after the initial infection[3,6,9]. Hepatic syphilis is unusual but is reported somewhat more frequently among men who have sex with men and in patients with HIV[12]. Notably, we reported a female patient with syphilis and a relatively healthy immune system. Accordingly, we speculate that the strength of the patient’s immunity might not be critical to pathogenesis and that delayed treatment with standardized anti-syphilis agents might induce multiple system injuries, including hepatic syphilis, especially inflammatory nodules.

We presented a case showing that when multiple hepatic nodules with primary lesions are confronted, focusing on infectious or self-immune diseases based on the patient’s history might help to answer the final question. A definite diagnosis should be made in conjunction with a medical history review for accurate therapeutic intervention.

| 1. | Clark AM, Ma B, Taylor DL, Griffith L, Wells A. Liver metastases: Microenvironments and ex-vivo models. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2016;241:1639-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Rashidian N, Alseidi A, Kirks RC. Cancers Metastatic to the Liver. Surg Clin North Am. 2020;100:551-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Hagen CE, Kamionek M, McKinsey DS, Misdraji J. Syphilis presenting as inflammatory tumors of the liver in HIV-positive homosexual men. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1636-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Baughn RE, Musher DM. Secondary syphilitic lesions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:205-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Maincent G, Labadie H, Fabre M, Novello P, Derghal K, Patriarche C, Licht H. Tertiary hepatic syphilis. A treatable cause of multinodular liver. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:447-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Mahto M, Mohammed F, Wilkins E, Mason J, Haboubi NY, Khan AN. Pseudohepatic tumour associated with secondary syphilis in an HIV-positive male. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17:139-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Shim HJ. Tertiary syphilis mimicking hepatic metastases of underlying primary peritoneal serous carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2010;2:362-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Otsuka Y, Minaga K, Watanabe T. An Overlooked Cause of Multiple Liver Nodules Exhibiting the Bull's-Eye Sign. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:548-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Huang J, Lin S, Wang M, Wan B, Zhu Y. Syphilitic hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Mullick CJ, Liappis AP, Benator DA, Roberts AD, Parenti DM, Simon GL. Syphilitic hepatitis in HIV-infected patients: a report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:e100-e105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Gaslightwala I, Khara HS, Diehl DL. Syphilitic gummas mistaken for liver metastases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:e109-e110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Manavi K, Dhasmana D, Cramb R. Prevalence of hepatitis in early syphilis among an HIV cohort. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23:e4-e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Peeters L, Van Vaerenbergh W, Van der Perre C, Lagrange W, Verbeke M. Tertiary syphilis presenting as hepatic bull's eye lesions. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2005;68:435-439. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Desilets A, Arsenault F, Laskine M. HIV-Infected Patient Diagnosed With Osteomedullary and Hepatic Syphilis on Positron Emission Tomography: A Case Report. J Clin Med Res. 2019;11:301-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Al Dallal HA, Narayanan S, Alley HF, Eiswerth MJ, Arnold FW, Martin BA, Shandiz AE. Case Report: Syphilitic Hepatitis-A Rare and Underrecognized Etiology of Liver Disease With Potential for Misdiagnosis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:789250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Smith MJ, Ong M, Maqbool A. Tertiary syphilis mimicking metastatic rectal cancer. J Surg Case Rep. 2022;2022:rjac093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |