Published online Jul 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i7.2925

Revised: March 28, 2024

Accepted: April 30, 2024

Published online: July 15, 2024

Processing time: 179 Days and 15.1 Hours

Little is known about disparities in diagnosis and treatment among colorectal cancer (CRC) patients with and without disabilities.

To investigate the patterns of diagnosis, treatment, and survival for people with and without disabilities who had CRC.

We performed a retrospective analysis using the Korean National Health Insurance Service database, disability registration data, and Korean Central Cancer Registry data. The analysis included 21449 patients with disabilities who were diagnosed with CRC and 86492 control patients diagnosed with CRC.

The overall distribution of CRC stage was not affected by disability status. Subjects with disabilities were less likely than those without disabilities to undergo surgery [adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 0.85; 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 0.82-0.88], chemotherapy (aOR: 0.84; 95%CI: 0.81-0.87), or radiotherapy (aOR: 0.90; 95%CI: 0.84-0.95). The rate of no treatment was higher in patients with disabilities than in those without disabilities (aOR: 1.48; 95%CI: 1.41-1.55). The overall mortality rate was higher in patients with disabilities [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR): 1.24; 95%CI: 1.22-1.28], particularly severe disabilities (aHR: 1.57; 95%CI: 1.51-1.63), than in those without disabilities.

Patients with severe disabilities tended to have a late or unknown diagnosis. Patients with CRC and disabilities had lower rates of treatment with almost all modalities compared with those without disabilities. During the follow-up period, the mortality rate was higher in patients with disabilities than in those without disabilities. The diagnosis and treatment of CRC need improvement in patients with disabilities.

Core Tip: Little is known about disparities in diagnosis, treatment, and survival among colorectal-cancer patients with and without disabilities. The overall distribution of colorectal cancer (CRC) stage was not affected by disability status. But disability affected the timing of diagnosis, treatment, and mortality, and this trend was more severe in cases of severe disability. Further research is needed to develop guidelines to ensure equal diagnosis and treatment of CRC in disabled and non-disabled patients.

- Citation: Kim KB, Shin DW, Yeob KE, Kim SY, Han JH, Park SM, Park JH, Park JH. Disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer among patients with disabilities. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(7): 2925-2940

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i7/2925.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i7.2925

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer death in South Korea[1-5]. Timely identification and proper treatment are essential to reduce the morbidity and mortality rate of CRC[6,7].

Socially marginalized groups, like those with low income or from ethnic minorities, frequently experience delayed cancer diagnoses, receive less comprehensive or unsuitable treatment, and have shorter survival times compared to those with better social circumstances[1-5,8]. There are no clear or consistent guidelines for diagnosis and treatment, catering to patients with various disability states or cancer types[9-11].

Few studies have investigated the disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of CRC according to disability status, mainly because of a lack of information on disabilities in existing databases[11-15]. Studies conducted in the United States that used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare/Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) database examined differences in cancer stage at diagnosis and survival in patients < 65 years of age[11] and investigated disparities in treatment and survival among patients with stage I CRC[9]. Even when diagnosed at the same stage, patients with disabilities had a greater likelihood of cancer-related death compared to patients without disabilities, which was attributable to treatment differences[11].

Although the largest of its kind to date, the studies mentioned above had certain limitations: (1) The use of Medicare/SSDI status as a measure of disability may not accurately capture all individuals with disabilities (e.g., individuals with disabilities who work are not eligible for medicare/SSDI); (2) they investigated only patients < 65 years of age, which restricts the sample’s representativeness; (3) healthcare access differed according to disability status (a considerable portion of patients without disabilities are under- or uninsured); (4) analyses of treatment were limited to stage I cancer, and chemotherapy information was not available; (5) only five disabilities were analyzed (i.e., visual and hearing disabilities were not included); and (6) information on disability severity was not available.

The population of South Korea is covered by universal health insurance, and the copay for cancer work-up and treatment is only 5%, with a maximum copay for low-income individuals of approximately 1000 USD as of 2016[16]. In addition, South Korea has a national disability registration system, which defines disability type and severity according to preset criteria and medical diagnosis[17]. These are optimal conditions for examining disparities in CRC care related to disabilities. Using an administrative database, we investigated disparities in the diagnosis, treatment, and survival of patients with CRC according to disability in South Korea.

The Korean National Health Insurance Service: The Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) provides public health insurance for 97% of South Koreans, and insurance premiums are based on income level. Almost 3% of the population with the lowest income is covered by Medicaid, which is funded by general taxation. Healthcare providers primarily receive reimbursement for their medical services through a fee-for-service model. Consequently, the NHIS contains all the requisite data for reimbursement, including disease codes, diagnostic tests and treatments, and prescription medications from inpatient and outpatient services. It also encompasses demographic data (e.g., age, sex, place of residence, and income status) for all South Koreans. The NHIS database is available for research upon approval, and its data have been used in a number of epidemiological and health policy studies[18-20]. Details of the database are available elsewhere[21,22]. The NHIS provides a free biennial cardiovascular health screening, which consists of a questionnaire on past medical history and health behaviors, anthropometric measurements, and laboratory tests, to individuals > 40 years of age and all employees irrespective of age[18].

The South Korean Disability Registration System: In 1988, the South Korean government established a national registration system for people with disabilities to determine the level of welfare benefits, based on the type and severity of disability. The legislation specifies 15 types of disability: Limb, brain, visual, auditory, linguistic, facial, kidney, heart, liver, respiratory system, ostomy, epilepsy, intellectual, autistic, and mental disabilities. The severity of a disability is legally classified into six levels and is assessed based on functional loss and clinical impairment by a medical specialist[23]. In this study, disabilities were classified as: (1) Physical impairment (limb disability and facial disfigurement); (2) communication impairment (visual, auditory, or linguistic disability); (3) brain impairment; (4) mental impairment (intellectual, autistic, or mental disability); (5) cardiopulmonary impairment (heart or lung disability); and (6) other internal organ impairment (disability due to renal disease, liver disease, respiratory disease, epilepsy, or ostomy). We dichotomized disability severity into severe (grades 1-3) and mild (grades 4-6)[24].

The South Korean Cancer Registration System: The Korean Central Cancer Registry (KCCR) is a government-sponsored, nationwide cancer registry that contains data on age at diagnosis, sex, date of diagnosis, cancer site, and SEER summary stage (in situ and local, regional, distant, and unknown).

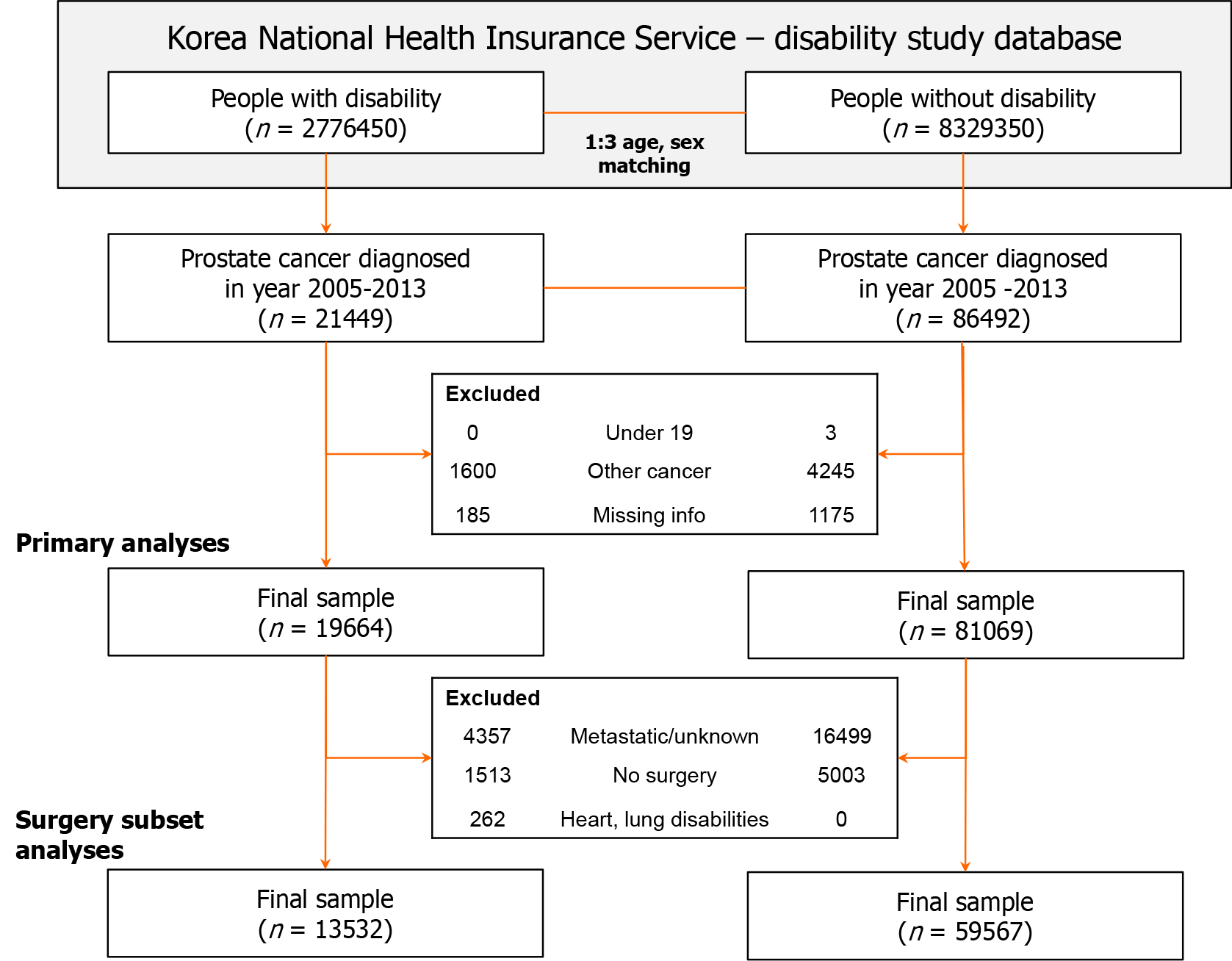

First, we linked the Korean NHIS database to national disability registration data and selected three control subjects for each patient with any registered disability, diagnosed between 2009 and 2013, by age and sex matching. Second, cancer registration data from the KCCR were linked for all subjects in the NHIS disability study dataset. The study population included all subjects diagnosed with CRC (International Classification of Disease codes C18-20 and D01) between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2013 (n = 21449 with disabilities and 86492 without disabilities). We excluded patients who were < 19 years of age at the time of diagnosis or index date (n = 0 and 3, respectively), had a history of other cancers before the diagnosis of CRC (n = 1600 and 4245, respectively), or had missing data (n = 185 and 1175, respectively). The final sample consisted of 100733 CRC patients, among whom 19664 had disabilities and 81069 did not (control subjects). Finally, we linked the dataset to mortality data from the Korean National Statistical Office; these data include the date and cause of death. To investigate the survival of CRC patients who underwent surgery with curative intent, the surgery subset comprised subjects with localized or locoregional CRC who underwent surgery. Patients with heart and lung disabilities were excluded because those disabilities may preclude surgery and could significantly affect perioperative mortality if surgery is performed. Finally, 73099 subjects (13532 with disabilities and 59567 without disabilities) comprised the surgery subset (Figure 1). Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Chungbuk National University (IRB No. CBNU-201708-BM-501-01). The requirement for informed consent was waived because this study was based on a secondary data source: An administrative database.

Summary statistics are presented according to disability status (i.e., the presence or absence of disabilities, and according to the six disability categories and disability severity). Cancer stage at diagnosis and treatment received were analyzed by chi-squared test. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy were considered binary variables because of the variety and complexity of the regimens and variable compliance. The relative probability of receiving a treatment (i.e., endoscopic removal, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy) or no treatment was assessed by logistic regression analyses with adjustments for age, sex, income level, place of residence, Charlson comorbidity index[25], and cancer stage. The correction variables we chose were based on the results of previous studies[18,20,24]. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was conducted to estimate the hazard ratios for overall and CRC-specific mortality of patients with vs those without disabilities. Survival duration was calculated from the date of CRC diagnosis until that of death (including CRC death), censoring (e.g., outmigration), or the last follow-up (December 31, 2015). The multivariate model included age, sex, income level, place of residence, Charlson comorbidity index, cancer stage, and treatment received. The analyses were repeated using the surgery subset. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (v9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). Values of P < 0.05 were considered indicative of statistical significance.

CRC patients with disabilities were comparable with the control subjects in terms of mean age (68.4 years vs 68.6 years) and sex distribution (female: 32.9% vs 33.8%). CRC patients with disabilities exhibited a higher prevalence of comorbidities and a greater mean Charlson comorbidity index score (2.4 vs 2.1). Additionally, they were more prone to lower income levels and residing in non-metropolitan areas compared to those without disabilities (Table 1).

| People without disabilities | People with disability | By disability grade | By disability type | |||||||

| Grades 1-3 | Grades 4-6 | Physical | Communication | Brain | Mental | Cardiopulmonary | Others | |||

| All subject, n | 81069 | 19664 | 6517 | 13147 | 10727 | 5267 | 2013 | 463 | 386 | 808 |

| Age, yr | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 68.6 (10.4) | 68.4 (10.5) | 67.8 (10.8) | 68.8 (10.3) | 67.3 (10.2) | 71.6 (10.4) | 70.4 (9.3) | 58.1 (11.5) | 69.2 (8.2) | 64.5 (10.7) |

| 19-40 | 700 (0.9) | 163 (0.8) | 80 (1.2) | 83 (0.6) | 81 (0.8) | 19 (0.4) | 7 (0.3) | 36 (7.8) | 0 (0) | 20 (2.5) |

| 40-65 | 27937 (34.5) | 6992 (35.6) | 2452 (37.6) | 4540 (34.5) | 4274 (39.8) | 1375 (26.1) | 533 (26.5) | 303 (65.4) | 120 (31.1) | 387 (47.9) |

| 65-75 | 31156 (38.4) | 7411 (37.7) | 2396 (36.8) | 5015 (38.1) | 4078 (38.0) | 1903 (36.1) | 872 (43.3) | 101 (21.8) | 188 (48.7) | 269 (33.3) |

| 75- | 21276 (26.2) | 5098 (25.9) | 1589 (24.4) | 3509 (26.7) | 2294 (21.4) | 1970 (37.4) | 601 (29.9) | 23 (5.0) | 78 (20.2) | 132 (16.3) |

| Female sex | 27371 (33.8) | 6460 (32.9) | 1928 (29.6) | 4532 (34.5) | 3717 (34.7) | 1612 (30.6) | 604 (30.0) | 180 (38.9) | 57 (14.8) | 290 (35.9) |

| Charlson comorbidity Score | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.0) |

| 0 | 31441 (38.8) | 5390 (27.4) | 1597 (24.5) | 3793 (28.9) | 3255 (30.3) | 1601 (30.4) | 228 (11.3) | 203 (43.8) | 33 (8.5) | 70 (8.7) |

| 1 | 20410 (25.2) | 4501 (22.9) | 1304 (20.0) | 3197 (24.3) | 2571 (24.0) | 1281 (24.3) | 395 (19.6) | 114 (24.6) | 87 (22.5) | 53 (6.6) |

| 2 | 12609 (15.6) | 3288 (16.7) | 1099 (16.9) | 2189 (16.7) | 1785 (16.6) | 900 (17.1) | 331 (16.4) | 64 (13.8) | 93 (24.1) | 115 (14.2) |

| 3 | 7370 (9.1) | 2378 (12.1) | 779 (12.0) | 1599 (12.2) | 1240 (11.6) | 596 (11.3) | 317 (15.7) | 36 (7.8) | 71 (18.4) | 118 (14.6) |

| ≥ 4 | 9239 (11.4) | 4107 (20.9) | 1738 (26.7) | 2369 (18.0) | 1876 (17.5) | 889 (16.9) | 742 (36.9) | 46 (9.9) | 102 (26.4) | 452 (55.9) |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||||

| Hypertension | 38225 (47.2) | 10902 (55.4) | 3798 (58.3) | 7104 (54.0) | 5550 (51.7) | 2832 (53.8) | 1580 (78.5) | 131 (28.3) | 241 (62.4) | 568 (70.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 19632 (24.2) | 6039 (30.7) | 2169 (33.3) | 3870 (29.4) | 3109 (29.0) | 1531 (29.1) | 776 (38.5) | 82 (17.7) | 148 (38.3) | 393 (48.6) |

| Coronary heart disease | 9014 (11.1) | 2737 (13.9) | 1046 (16.1) | 1691 (12.9) | 1343 (12.5) | 697 (13.2) | 300 (14.9) | 25 (5.4) | 143 (37.0) | 229 (28.3) |

| Stroke | 4240 (5.2) | 2377 (12.1) | 1130 (17.3) | 1247 (9.5) | 789 (7.4) | 466 (8.8) | 998 (49.6) | 24 (5.2) | 28 (7.3) | 72 (8.9) |

| COPD | 19331 (23.8) | 5691 (28.9) | 1879 (28.8) | 3812 (29.0) | 3002 (28.0) | 1585 (30.1) | 522 (25.9) | 89 (19.2) | 267 (69.2) | 226 (28.0) |

| Income | ||||||||||

| Medical aid | 3816 (4.7) | 2536 (12.9) | 1329 (20.4) | 1207 (9.2) | 1155 (10.8) | 636 (12.1) | 287 (14.3) | 254 (54.9) | 59 (15.3) | 145 (17.9) |

| 1st quartile (lowest) | 13784 (17.0) | 3430 (17.4) | 955 (14.7) | 2475 (18.8) | 2019 (18.8) | 929 (17.6) | 255 (12.7) | 51 (11.0) | 51 (13.2) | 125 (15.5) |

| 2nd quartile | 13123 (16.2) | 3067 (15.6) | 946 (14.5) | 2121 (16.1) | 1759 (16.4) | 807 (15.3) | 272 (13.5) | 46 (9.9) | 63 (16.3) | 120 (14.9) |

| 3rd quartile | 18562 (22.9) | 4177 (21.2) | 1288 (19.8) | 2889 (22.0) | 2352 (21.9) | 1081 (20.5) | 455 (22.6) | 55 (11.9) | 90 (23.3) | 144 (17.8) |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 31784 (39.2) | 6454 (32.8) | 1999 (30.7) | 4455 (33.9) | 3442 (32.1) | 1814 (34.4) | 744 (37.0) | 57 (12.3) | 123 (31.9) | 274 (33.9) |

| Place of residence | ||||||||||

| Metropolitan | 46929 (57.9) | 10620 (54.0) | 3585 (55.0) | 7035 (53.5) | 5646 (52.6) | 2825 (53.6) | 1198 (59.5) | 221 (47.7) | 210 (54.4) | 520 (64.4) |

| City | 22329 (27.5) | 6009 (30.6) | 1983 (30.4) | 4026 (30.6) | 3341 (31.1) | 1633 (31.0) | 549 (27.3) | 147 (31.7) | 120 (31.1) | 219 (27.1) |

| Rural | 11811 (14.6) | 3035 (15.4) | 949 (14.6) | 2086 (15.9) | 1740 (16.2) | 809 (15.4) | 266 (13.2) | 95 (20.5) | 56 (14.5) | 69 (8.5) |

| Type of cancer | ||||||||||

| Colon | 44269 (54.6) | 10985 (55.9) | 3711 (56.9) | 7274 (55.3) | 5876 (54.8) | 2949 (56.0) | 1182 (58.7) | 278 (60.0) | 224 (58) | 476 (58.9) |

| Rectosigmoid | 6123 (7.6) | 1591 (8.1) | 530 (8.1) | 1061 (8.1) | 860 (8.0) | 449 (8.5) | 164 (8.1) | 46 (9.9) | 24 (6.2) | 48 (5.9) |

| Rectum | 30677 (37.8) | 7088 (36.0) | 2276 (34.9) | 4812 (36.6) | 3991 (37.2) | 1869 (35.5) | 667 (33.1) | 139 (30.0) | 138 (35.8) | 284 (35.1) |

| Clinical disease status | ||||||||||

| Localized | 29934 (36.9) | 7322 (37.2) | 2283 (35.0) | 5039 (38.3) | 4201 (39.2) | 1829 (34.7) | 664 (33.0) | 123 (26.6) | 150 (38.9) | 355 (43.9) |

| Locoregional | 34636 (42.7) | 7985 (40.6) | 2617 (40.2) | 5368 (40.8) | 4319 (40.3) | 2243 (42.6) | 832 (41.3) | 193 (41.7) | 142 (36.8) | 256 (31.7) |

| Metastatic | 9387 (11.6) | 2484 (12.6) | 889 (13.6) | 1595 (12.1) | 1279 (11.9) | 681 (12.9) | 298 (14.8) | 88 (19.0) | 50 (13.0) | 88 (10.9) |

| Unknown | 7112 (8.8) | 1873 (9.5) | 728 (11.2) | 1145 (8.7) | 928 (8.7) | 514 (9.8) | 219 (10.9) | 59 (12.7) | 44 (11.4) | 109 (13.5) |

| Treatment within 6 months of diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Polypectomy, EMR, or ESD | 11527 (14.2) | 2849 (14.5) | 877 (13.5) | 1972 (15.0) | 1683 (15.7) | 677 (12.9) | 223 (11.1) | 43 (9.3) | 63 (16.3) | 160 (19.8) |

| Surgery only | 31118 (38.4) | 7611 (38.7) | 2492 (38.2) | 5119 (38.9) | 4052 (37.8) | 2132 (40.5) | 801 (39.8) | 162 (35.0) | 147 (38.1) | 317 (39.2) |

| Surgery + RT | 2959 (3.6) | 587 (3.0) | 170 (2.6) | 417 (3.2) | 347 (3.2) | 149 (2.8) | 50 (2.5) | 11 (2.4) | 15 (3.9) | 15 (1.9) |

| Surgery + Chemo | 19409 (23.9) | 4140 (21.1) | 1233 (18.9) | 2907 (22.1) | 2467 (23.0) | 1058 (20.1) | 329 (16.3) | 113 (24.4) | 68 (17.6) | 105 (13.0) |

| Surgery + CCRT | 5339 (6.6) | 1034 (5.3) | 310 (4.8) | 724 (5.5) | 617 (5.8) | 284 (5.4) | 79 (3.9) | 17 (3.7) | 20 (5.2) | 17 (2.1) |

| CCRT | 691 (0.9) | 171 (0.9) | 68 (1.0) | 103 (0.8) | 82 (0.8) | 50 (0.9) | 15 (0.7) | 4 (0.9) | 11 (2.8) | 9 (1.1) |

| Chemo only | 2023 (2.5) | 558 (2.8) | 201 (3.1) | 357 (2.7) | 300 (2.8) | 134 (2.5) | 65 (3.2) | 23 (5.0) | 12 (3.1) | 24 (3.0) |

| RT only | 557 (0.7) | 155 (0.8) | 58 (0.9) | 97 (0.7) | 82 (0.8) | 44 (0.8) | 11 (0.5) | 4 (0.9) | 5 (1.3) | 9 (1.1) |

| No treatment | 7446 (9.2) | 2559 (13.0) | 1108 (17.0) | 1451 (11.0) | 1097 (10.2) | 739 (14.0) | 440 (21.9) | 86 (18.6) | 45 (11.7) | 152 (18.8) |

| Screening subset, n | 18760 | 3866 | 856 | 3010 | 2447 | 1072 | 216 | 27 | 53 | 51 |

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Current | 5935 (31.6) | 1161 (30.0) | 267 (31.2) | 894 (29.7) | 754 (30.8) | 319 (29.8) | 58 (26.9) | 9 (33.3) | 7 (13.2) | 14 (27.5) |

| Past | 5146 (27.4) | 1054 (27.3) | 223 (26.1) | 831 (27.6) | 664 (27.1) | 290 (27.1) | 64 (29.6) | 6 (22.2) | 21 (39.6) | 9 (17.6) |

| Non | 7679 (40.9) | 1651 (42.7) | 366 (42.8) | 1285 (42.7) | 1029 (42.1) | 463 (43.2) | 94 (43.5) | 12 (44.4) | 25 (47.2) | 28 (54.9) |

| Alcohol intake | ||||||||||

| Non-drinker | 2082 (11.1) | 596 (15.4) | 151 (17.6) | 445 (14.8) | 353 (14.4) | 149 (13.9) | 47 (21.8) | 11 (40.7) | 19 (35.8) | 17 (33.3) |

| Social amount | 16096 (85.8) | 3128 (80.9) | 681 (79.6) | 2447 (81.3) | 2007 (82.0) | 873 (81.4) | 168 (77.8) | 15 (55.6) | 33 (62.3) | 32 (62.7) |

| Heavy drinker | 582 (3.1) | 142 (3.7) | 24 (2.8) | 118 (3.9) | 87 (3.6) | 50 (4.7) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||||||||

| < 18.5 | 484 (2.6) | 100 (2.6) | 39 (4.6) | 61 (2) | 52 (2.1) | 34 (3.2) | 6 (2.8) | 2 (7.4) | 6 (11.3) | 0 (0) |

| 18.5-23.0 | 6105 (32.5) | 1260 (32.6) | 314 (36.7) | 946 (31.4) | 760 (31.1) | 367 (34.2) | 77 (35.6) | 11 (40.7) | 24 (45.3) | 21 (41.2) |

| 23.0-25.0 | 5227 (27.9) | 1009 (26.1) | 201 (23.5) | 808 (26.8) | 650 (26.6) | 281 (26.2) | 49 (22.7) | 8 (29.6) | 10 (18.9) | 11 (21.6) |

| 25.0-30.0 | 6438 (34.3) | 1347 (34.8) | 270 (31.5) | 1077 (35.8) | 878 (35.9) | 358 (33.4) | 77 (35.6) | 6 (22.2) | 12 (22.6) | 16 (31.4) |

| ≥ 30.0 | 506 (2.7) | 150 (3.9) | 32 (3.7) | 118 (3.9) | 107 (4.4) | 32 (3.0) | 7 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (5.9) |

The stage distribution was similar between patients with and those without disabilities. However, patients with severe disabilities were slightly more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage (12.6% vs 11.6%) or to have an unknown stage (9.5% vs 8.8%), particularly those with mental impairment (12.7%), brain impairment (12.2%), or communication impairment (12.0%) (Table 2).

| All | By cancer stage | P value | ||||

| Localized | Locoregional | Distant | Unknown | |||

| No. of patients | 100733 | 37256 (37.0) | 42621 (42.3) | 11871 (11.8) | 8985 (8.9) | |

| People without disabilities | 81069 | 29934 (36.9) | 34636 (42.7) | 9387 (11.6) | 7112 (8.8) | < 0.0001 |

| People with disability | 19664 | 7322 (37.2) | 7985 (40.6) | 2484 (12.6) | 1873 (9.5) | |

| By disability grades | ||||||

| Severe (Grades 1-3) | 6517 | 2283 (35.0) | 2617 (40.2) | 889 (13.6) | 728 (11.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Mild (Grades 4-6) | 13147 | 5039 (38.3) | 5368 (40.8) | 1595 (12.1) | 1145 (8.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Grade 1 | 986 | 309 (31.3) | 365 (37.0) | 170 (17.2) | 142 (14.4) | |

| Grade 2 | 2402 | 872 (36.3) | 953 (39.7) | 299 (12.4) | 278 (11.6) | |

| Grade 3 | 3129 | 1102 (35.2) | 1299 (41.5) | 420 (13.4) | 308 (9.8) | |

| Grade 4 | 3531 | 1276 (36.1) | 1447 (41.0) | 470 (13.3) | 338 (9.6) | |

| Grade 5 | 4695 | 1812 (38.6) | 1888 (40.2) | 573 (12.2) | 422 (9.0) | |

| Grade 6 | 4921 | 1951 (39.6) | 2033 (41.3) | 552 (11.2) | 385 (7.8) | |

| By disability types | ||||||

| Physical | ||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 2306 | 853 (37.0) | 937 (40.6) | 293 (12.7) | 223 (9.7) | |

| Grades 4-6 | 8421 | 3348 (39.8) | 3382 (40.2) | 986 (11.7) | 705 (8.4) | |

| Communication | ||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 1423 | 464 (32.6) | 596 (41.9) | 192 (13.5) | 171 (12.0) | |

| Grades 4-6 | 3844 | 1365 (35.5) | 1647 (42.8) | 489 (12.7) | 343 (8.9) | |

| Brain | ||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 1400 | 438 (31.3) | 572 (40.9) | 219 (15.6) | 171 (12.2) | |

| Grades 4-6 | 613 | 226 (36.9) | 260 (42.4) | 79 (12.9) | 48 (7.8) | |

| Mental | ||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 463 | 123 (26.6) | 193 (41.7) | 88 (19.0) | 59 (12.7) | |

| Grades 4-6 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Cardiopulmonary | ||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 385 | 149 (38.7) | 142 (36.9) | 50 (13.0) | 44 (11.4) | |

| Grades 4-6 | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Others | ||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 540 | 256 (47.4) | 177 (32.8) | 47 (8.7) | 60 (11.1) | |

| Grades 4-6 | 268 | 99 (36.9) | 79 (29.5) | 41 (15.3) | 49 (18.3) | |

The rate of endoscopic resection differed insignificantly between subjects with and those without disabilities [14.5% vs 14.2%, respectively; adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.02, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 0.95-1.05]. However, subjects with disabilities were less likely than those without disabilities to undergo surgery (68.1% vs 72.5%), chemotherapy (30.0% vs 33.9%), or radiotherapy (9.9% vs 11.8%) [aOR (95%CI): 0.85 [0.82-0.88] for surgery, 0.84 (0.81-0.87) for chemotherapy, and 0.90 (0.84-0.95) for radiotherapy]. This trend was more evident in subjects with severe disabilities [aOR (95%CI): 0.74 (0.70-0.79) for surgery, 0.70 (0.66-0.75) for chemotherapy, and 0.87 (0.78-0.96) for radiotherapy] compared with those with mild disabilities. The rate of no treatment was higher in subjects with disabilities (13.0% vs 9.2%; aOR: 1.48, 95%CI: 1.41-1.55), including those with severe disabilities (17.0%; aOR: 2.02; 95%CI: 1.89-2.17).

Subjects with severe physical impairment were less likely to undergo surgery (aOR: 0.79; 95%CI: 0.72-0.87) or chemotherapy (aOR: 0.81; 95%CI: 0.73-0.89), but not radiotherapy or endoscopic mucosal resection compared with those without disabilities. People with severe communication impairment were less likely to receive chemotherapy compared with those without disabilities (aOR: 0.86; 95%CI: 0.73-0.89). Subjects with severe brain impairment or severe mental impairment were less likely to receive all types of treatment compared with those without disabilities. Subjects with severe cardiopulmonary impairment had a lower likelihood of undergoing surgery (aOR: 0.78; 95%CI: 0.62-0.98) but a higher likelihood of receiving radiotherapy (aOR: 1.47; 95%CI: 1.04-2.08) compared with those without disabilities (Table 3). The treatments according to stage at diagnosis are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

| Overall mortality | Total No. | Polypectomy, EMR, ESD | Surgery+ | CT+ | RT+ | No treatment | |||||||||||||||

| No | Yes | Model 1 | Model 2 | No | Yes | Model 1 | Model 2 | No | Yes | Model 1 | Model 2 | No | Yes | Model 1 | Model 2 | No | Yes | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| Disability | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-disabled patients | 81069 | 69542 | 11527 | REF | REF | 22244 | 58825 | REF | REF | 53607 | 27462 | REF | REF | 71523 | 9546 | REF | REF | 73623 | 7446 | REF | REF |

| Disabled patients | 19664 | 16815 | 2849 | 1.022 (0.978-1.069) | 0.998 (0.951-1.048) | 6292 | 13372 | 0.804 (0.777-0.831) | 0.848 (0.817-0.88) | 13761 | 5903 | 0.837 (0.81-0.866) | 0.837 (0.805-0.87) | 17717 | 1947 | 0.823 (0.782-0.867) | 0.895 (0.844-0.950) | 17105 | 2559 | 1.479 (1.410-1.552) | 1.389 (1.318-1.464) |

| By disability severity | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 6517 | 5640 | 877 | 0.938 (0.871-1.010) | 0.909 (0.839-0.986) | 2312 | 4205 | 0.688 (0.652-0.725) | 0.743 (0.700-0.789) | 4705 | 1812 | 0.752 (0.711-0.795) | 0.703 (0.660-0.749) | 5911 | 606 | 0.768 (0.705-0.837) | 0.866 (0.784-0.956) | 5409 | 1108 | 2.025 (1.891-2.170) | 1.884 (1.744-2.034) |

| Grades 4-6 | 13147 | 11175 | 1972 | 1.065 (1.011-1.121) | 1.041 (0.984-1.101) | 3980 | 9167 | 0.871 (0.837-0.907) | 0.904 (0.865-0.945) | 9056 | 4091 | 0.882 (0.848-0.918) | 0.908 (0.868-0.949) | 11806 | 1341 | 0.851 (0.801-0.904) | 0.909 (0.849-0.974) | 11696 | 1451 | 1.227 (1.156-1.302) | 1.166 (1.093-1.243) |

| Grade 1 | 986 | 879 | 107 | 0.735 (0.601-0.899) | 0.741 (0.598-0.918) | 415 | 571 | 0.520 (0.458-0.591) | 0.592 (0.513-0.684) | 756 | 230 | 0.594 (0.512-0.689) | 0.508 (0.431-0.598) | 910 | 76 | 0.626 (0.495-0.792) | 0.772 (0.594-1.004) | 731 | 255 | 3.452 (2.987-3.988) | 2.913 (2.476-3.428) |

| Grade 2 | 2402 | 2061 | 341 | 0.998 (0.889-1.121) | 0.941 (0.829-1.068) | 877 | 1525 | 0.657 (0.604-0.715) | 0.718 (0.653-0.789) | 1786 | 616 | 0.673 (0.614-0.739) | 0.655 (0.591-0.727) | 2209 | 193 | 0.655 (0.564-0.760) | 0.811 (0.686-0.959) | 1982 | 420 | 2.095 (1.881-2.334) | 1.917 (1.701-2.160) |

| Grade 3 | 3129 | 2700 | 429 | 0.959 (0.864-1.063) | 0.937 (0.838-1.049) | 1020 | 2109 | 0.782 (0.724-0.844) | 0.821 (0.755-0.894) | 2163 | 966 | 0.872 (0.807-0.942) | 0.811 (0.743-0.884) | 2792 | 337 | 0.904 (0.806-1.015) | 0.927 (0.813-1.058) | 2696 | 433 | 1.588 (1.431-1.762) | 1.555 (1.388-1.742) |

| Grade 4 | 3531 | 3038 | 493 | 0.979 (0.888-1.079) | 1.040 (0.936-1.155) | 1097 | 2434 | 0.839 (0.780-0.902) | 0.891 (0.823-0.966) | 2478 | 1053 | 0.830 (0.771-0.893) | 0.871 (0.802-0.946) | 3193 | 338 | 0.793 (0.708-0.889) | 0.893 (0.784-1.016) | 3075 | 456 | 1.466 (1.325-1.622) | 1.242 (1.113-1.385) |

| Grade 5 | 4695 | 4007 | 688 | 1.036 (0.953-1.126) | 1.018 (0.931-1.114) | 1460 | 3235 | 0.838 (0.786-0.893) | 0.889 (0.829-0.953) | 3298 | 1397 | 0.827 (0.775-0.882) | 0.896 (0.833-0.963) | 4240 | 455 | 0.804 (0.728-0.888) | 0.882 (0.788-0.986) | 4136 | 559 | 1.336 (1.220-1.464) | 1.190 (1.078-1.314) |

| Grade 6 | 4921 | 4130 | 791 | 1.155 (1.068-1.250) | 1.062 (0.975-1.157) | 1423 | 3498 | 0.930 (0.872-0.991) | 0.928 (0.866-0.994) | 3280 | 1641 | 0.977 (0.919-1.038) | 0.944 (0.881-1.011) | 4373 | 548 | 0.939 (0.857-1.029) | 0.944 (0.851-1.048) | 4485 | 436 | 0.961 (0.869-1.064) | 1.076 (0.966-1.198) |

| By disability type | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 2306 | 1968 | 338 | 1.036 (0.922-1.165) | 0.966 (0.851-1.097) | 763 | 1543 | 0.765 (0.700-0.835) | 0.791 (0.717-0.871) | 1573 | 733 | 0.910 (0.832-0.994) | 0.806 (0.729-0.891) | 2058 | 248 | 0.903 (0.790-1.032) | 0.894 (0.768-1.041) | 1997 | 309 | 1.530 (1.354-1.729) | 1.636 (1.431-1.870) |

| Grades 4-6 | 8421 | 7076 | 1345 | 1.147 (1.078-1.220) | 1.100 (1.028-1.176) | 2481 | 5940 | 0.905 (0.862-0.951) | 0.925 (0.877-0.977) | 5688 | 2733 | 0.938 (0.894-0.984) | 0.937 (0.887-0.989) | 7541 | 880 | 0.874 (0.813-0.941) | 0.895 (0.824-0.973) | 7633 | 788 | 1.021 (0.945-1.103) | 1.028 (0.946-1.116) |

| Communication | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 1423 | 1255 | 168 | 0.808 (0.687-0.950) | 0.883 (0.743-1.050) | 460 | 963 | 0.792 (0.708-0.886) | 0.888 (0.784-1.005) | 1012 | 411 | 0.793 (0.706-0.890) | 0.855 (0.751-0.973) | 1291 | 132 | 0.766 (0.640-0.917) | 0.907 (0.74-1.112) | 1193 | 230 | 1.906 (1.652-2.200) | 1.429 (1.221-1.671) |

| Grades 4-6 | 3844 | 3335 | 509 | 0.921 (0.837-1.013) | 0.967 (0.872-1.072) | 1184 | 2660 | 0.850 (0.792-0.911) | 0.899 (0.832-0.971) | 2729 | 1115 | 0.798 (0.743-0.856) | 0.883 (0.816-0.957) | 3449 | 395 | 0.858 (0.772-0.954) | 1.008 (0.893-1.138) | 3335 | 509 | 1.509 (1.371-1.662) | 1.266 (1.141-1.406) |

| Brain | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 1400 | 1260 | 140 | 0.670 (0.562-0.799) | 0.684 (0.568-0.824) | 560 | 840 | 0.567 (0.509-0.632) | 0.606 (0.537-0.685) | 1089 | 311 | 0.557 (0.491-0.633) | 0.537 (0.467-0.617) | 1295 | 105 | 0.607 (0.497-0.742) | 0.758 (0.606-0.948) | 1046 | 354 | 3.346 (2.959-3.784) | 2.935 (2.557-3.370) |

| Grades 4-6 | 613 | 530 | 83 | 0.945 (0.749-1.192) | 0.898 (0.699-1.153) | 194 | 419 | 0.817 (0.688-0.969) | 0.838 (0.695-1.012) | 436 | 177 | 0.792 (0.665-0.944) | 0.808 (0.664-0.982) | 563 | 50 | 0.665 (0.498-0.889) | 0.792 (0.573-1.093) | 527 | 86 | 1.614 (1.283-2.029) | 1.651 (1.287-2.119) |

| Mental | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 463 | 420 | 43 | 0.618 (0.451-0.846) | 0.696 (0.498-0.973) | 160 | 303 | 0.716 (0.591-0.868) | 0.773 (0.622-0.960) | 306 | 157 | 1.002 (0.826-1.215) | 0.588 (0.475-0.728) | 427 | 36 | 0.632 (0.449-0.888) | 0.627 (0.428-0.919) | 377 | 86 | 2.256 (1.782-2.854) | 2.366 (1.827-3.064) |

| Grades 4-6 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cardiopulmonary | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 385 | 323 | 62 | 1.158 (0.882-1.521) | 0.970 (0.724-1.301) | 135 | 250 | 0.700 (0.568-0.864) | 0.780 (0.620-0.981) | 274 | 111 | 0.791 (0.634-0.986) | 0.828 (0.648-1.059) | 334 | 51 | 1.144 (0.851-1.537) | 1.471 (1.039-2.081) | 340 | 45 | 1.309 (0.958-1.788) | 1.304 (0.934-1.822) |

| Grades 4-6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 0 | - | - | 1 | 0 | - | - | 1 | 0 | - | - | 1 | 0 | - | - |

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 540 | 414 | 126 | 1.836 (1.503-2.244) | 1.387 (1.111-1.731) | 234 | 306 | 0.494 (0.417-0.587) | 0.573 (0.474-0.693) | 451 | 89 | 0.385 (0.307-0.484) | 0.406 (0.317-0.520) | 506 | 34 | 0.503 (0.356-0.713) | 0.691 (0.469-1.018) | 456 | 84 | 1.821 (1.441-2.301) | 1.858 (1.441-2.396) |

| Grades 4-6 | 268 | 234 | 34 | 0.877 (0.611-1.257) | 0.659 (0.451-0.962) | 120 | 148 | 0.466 (0.366-0.594) | 0.579 (0.444-0.756) | 202 | 66 | 0.638 (0.483-0.842) | 0.579 (0.426-0.787) | 252 | 16 | 0.476 (0.287-0.789) | 0.412 (0.241-0.706) | 200 | 68 | 3.362 (2.551-4.431) | 3.286 (2.415-4.472) |

Over a mean follow-up of 6.3 years, 34.5% of the subjects died. The overall mortality risk was higher in CRC patients with disabilities than in those without disabilities [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR): 1.24; 95%CI: 1.21-1.28]. This difference was even greater among subjects with severe disabilities (aHR: 1.57; 95%CI: 1.51-1.63), but less prevalent in those with mild disabilities (aHR: 1.10; 95%CI: 1.06-1.13). Among subjects with severe disabilities, the mortality risk was markedly higher in those with internal organ (aHR: 2.43; 95%CI: 2.18-2.72), mental (aHR: 2.23; 95%CI: 1.95-2.55), or brain (aHR: 1.95; 95%CI: 1.82-2.09) impairment and was slightly higher in those with physical (aHR: 1.31; 95%CI: 1.23-1.40) or communication (aHR: 1.25; 95%CI: 1.15-1.35) impairment. Regarding CRC-specific mortality, 70.2% (24365 of 34716) of all deaths were linked to CRC. Similar values were obtained when the analysis was limited to participants of the screening program, with further adjustments for smoking, alcohol, and body mass index (aHR: 3 model) (Table 4, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

| Overall mortality | Overall mortality | Cancer-specific mortality | ||||||

| Total No. | No. of death | Incidence rate (per 1000 PY) | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | Total No. | No. of death | Incidence rate (per 1000 PY) | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | |

| Disability | ||||||||

| Non-disabled patients | 81069 | 26908 | 51.3 | REF | 81069 | 19011 | 36.3 | REF |

| Disabled patients | 19664 | 7808 | 70.9 | 1.244 (1.213-1.277) | 19664 | 5354 | 48.6 | 1.192 (1.156-1.229) |

| By disability severity | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 6517 | 3181 | 94.8 | 1.569 (1.512-1.630) | 6517 | 2091 | 62.3 | 1.430 (1.366-1.498) |

| Grades 4-6 | 13147 | 4627 | 60.5 | 1.095 (1.061-1.130) | 13147 | 3263 | 42.7 | 1.081 (1.042-1.123) |

| Grade 1 | 986 | 553 | 124.4 | 1.853 (1.702-2.017) | 986 | 408 | 91.8 | 1.831 (1.659-2.022) |

| Grade 2 | 2402 | 1260 | 105.0 | 1.731 (1.634-1.833) | 2402 | 775 | 64.6 | 1.502 (1.397-1.616) |

| Grade 3 | 3129 | 1368 | 79.9 | 1.372 (1.299-1.449) | 3129 | 908 | 53.0 | 1.259 (1.177-1.346) |

| Grade 4 | 3531 | 1415 | 72.1 | 1.202 (1.139-1.269) | 3531 | 1004 | 51.2 | 1.194 (1.120-1.272) |

| Grade 5 | 4695 | 1704 | 63.8 | 1.097 (1.044-1.152) | 4695 | 1213 | 45.4 | 1.092 (1.030-1.157) |

| Grade 6 | 4921 | 1508 | 50.0 | 1.011 (0.960-1.065) | 4921 | 1046 | 34.7 | 0.984 (0.924-1.047) |

| By disability type | ||||||||

| Physical | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 2306 | 912 | 68.3 | 1.311 (1.227-1.401) | 2306 | 649 | 48.6 | 1.290 (1.192-1.396) |

| Grades 4-6 | 8421 | 2675 | 53.0 | 1.044 (1.003-1.087) | 8421 | 1914 | 37.9 | 1.042 (0.994-1.093) |

| Communication | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 1423 | 659 | 85.9 | 1.245 (1.152-1.346) | 1423 | 446 | 58.1 | 1.170 (1.065-1.286) |

| Grades 4-6 | 3844 | 1562 | 73.0 | 1.136 (1.080-1.196) | 3844 | 1091 | 51.0 | 1.115 (1.048-1.185) |

| Brain | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 1400 | 853 | 144.7 | 1.947 (1.817-2.086) | 1400 | 601 | 101.9 | 1.897 (1.747-2.060) |

| Grades 4-6 | 613 | 275 | 88.4 | 1.490 (1.322-1.678) | 613 | 178 | 57.3 | 1.369 (1.181-1.588) |

| Mental | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 463 | 219 | 102.1 | 2.230 (1.948-2.553) | 463 | 173 | 80.6 | 2.074 (1.781-2.417) |

| Grades 4-6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cardiopulmonary | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 385 | 212 | 110.1 | 1.754 (1.532-2.008) | 385 | 107 | 55.6 | 1.257 (1.039-1.520) |

| Grades 4-6 | 1 | 1 | 740.9 | 19.971 (2.836-140.612) | 1 | 1 | 740.9 | 40.45 (5.691-287.489) |

| Others | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 540 | 326 | 126.2 | 2.434 (2.179-2.719) | 540 | 115 | 44.5 | 1.318 (1.096-1.586) |

| Grades 4-6 | 268 | 114 | 74.0 | 1.191 (0.990-1.432) | 268 | 79 | 51.3 | 1.167 (0.935-1.456) |

The overall mortality rate was higher in CRC patients with disabilities than in those with no disabilities (aHR: 1.23; 95%CI: 1.19-1.28). This difference was markedly higher among patients with severe disabilities (aHR: 1.62; 95%CI: 1.54-1.72) and slightly higher among those with mild disabilities (aHR: 1.09; 95%CI: 1.04-1.14). Among the subjects with severe disabilities, the mortality risk was significantly higher among those with internal organ (aHR: 3.22; 95%CI: 2.81-3.70), mental (aHR: 2.02; 95%CI: 1.63-2.50), or brain (aHR: 2.01; 95%CI: 1.82-2.23) impairment and was slightly higher among those with physical (aHR: 1.31; 95%CI: 1.19-1.44) or communication (aHR: 1.27; 95%CI: 1.13-1.43) impairment. Again, estimates were consistent with CRC-specific mortality when the analysis was limited to participants of the screening program (Table 5, Supplementary Tables 5 and 6).

| Overall mortality | Overall mortality | Cancer-specific mortality | ||||||

| Total No. | No. of death | Incidence rate (per 1000 PY) | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | Total No. | No. of death | Incidence rate (per 1000 PY) | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | |

| Disability | ||||||||

| Non-disabled patients | 59567 | 13842 | 32.7 | REF | 59567 | 8024 | 19.0 | REF |

| Disabled patients | 13532 | 3669 | 42.5 | 1.234 (1.189-1.280) | 13532 | 2021 | 23.4 | 1.171 (1.114-1.23) |

| By disability severity | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 4045 | 1400 | 56.3 | 1.624 (1.535-1.717) | 4045 | 733 | 29.5 | 1.453 (1.345-1.569) |

| Grades 4-6 | 9487 | 2269 | 36.9 | 1.086 (1.038-1.135) | 9487 | 1288 | 20.9 | 1.059 (0.998-1.123) |

| Grade 1 | 539 | 191 | 59.0 | 1.677 (1.452-1.936) | 539 | 116 | 35.8 | 1.698 (1.411-2.042) |

| Grade 2 | 1522 | 624 | 70.6 | 1.993 (1.837-2.162) | 1522 | 295 | 33.4 | 1.638 (1.456-1.842) |

| Grade 3 | 1984 | 585 | 45.8 | 1.349 (1.242-1.467) | 1984 | 322 | 25.2 | 1.260 (1.127-1.410) |

| Grade 4 | 2459 | 671 | 43.1 | 1.182 (1.094-1.278) | 2459 | 392 | 25.2 | 1.181 (1.067-1.308) |

| Grade 5 | 3342 | 827 | 38.7 | 1.118 (1.042-1.200) | 3342 | 476 | 22.3 | 1.104 (1.006-1.212) |

| Grade 6 | 3686 | 771 | 31.3 | 0.988 (0.918-1.062) | 3686 | 420 | 17.1 | 0.927 (0.840-1.023) |

| By disability type | ||||||||

| Physical | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 1601 | 429 | 40.8 | 1.310 (1.189-1.443) | 1601 | 251 | 23.9 | 1.303 (1.148-1.479) |

| Grades 4-6 | 6204 | 1300 | 31.8 | 1.009 (0.953-1.069) | 6204 | 756 | 18.5 | 0.995 (0.923-1.072) |

| Communication | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 940 | 299 | 49.1 | 1.270 (1.132-1.425) | 940 | 166 | 27.3 | 1.211 (1.038-1.413) |

| Grades 4-6 | 2697 | 780 | 45.6 | 1.145 (1.065-1.231) | 2697 | 434 | 25.4 | 1.113 (1.010-1.226) |

| Brain | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 844 | 376 | 81.1 | 2.014 (1.816-2.233) | 844 | 210 | 45.3 | 1.938 (1.688-2.226) |

| Grades 4-6 | 438 | 144 | 56.7 | 1.555 (1.319-1.834) | 438 | 75 | 29.5 | 1.420 (1.131-1.784) |

| Mental | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 281 | 86 | 53.5 | 2.016 (1.626-2.499) | 281 | 56 | 34.8 | 1.811 (1.387-2.365) |

| Grades 4-6 | ||||||||

| Others | ||||||||

| Grades 1-3 | 379 | 210 | 104.6 | 3.224 (2.807-3.704) | 379 | 50 | 24.9 | 1.459 (1.102-1.931) |

| Grades 4-6 | 148 | 45 | 46.3 | 1.974 (1.473-2.647) | 148 | 23 | 23.7 | 1.775 (1.178-2.674) |

To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the diagnosis, treatment, and mortality rate of CRC associated with disabilities. This study included a large, representative population, which encompassed a wide range of disabilities, and involved objective assessments of disabilities.

The distribution of CRC stage was similar between disabled and non-disabled subjects, but the more severe the mental, brain, or communication disability, the later the diagnosis. An unknown stage indicates that the patient did not undergo adequate diagnostic testing to develop an appropriate treatment plan. Disability itself does not preclude cancer treatment, suggesting that society’s attitude hampers the treatment of disabled patients with CRC.

The rates of endoscopic resection were similar for subjects with and those without disabilities, possibly because endoscopic resection requires shorter hospitalization compared with other treatments[26]. By contrast, subjects with disabilities, and particularly those with severe disabilities, undergo surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy less frequently. Subjects with disabilities, and particularly those with severe disabilities were more likely not to be treated. Subjects with physical disabilities had lower rates of surgery and chemotherapy, but similar rates of radiotherapy and endoscopic resection, compared with those without physical disabilities. Subjects with communication disabilities were unlikely to receive chemotherapy. Communication barriers can hinder effective communication with healthcare providers, making it harder to assess their condition, determine treatment options. Healthcare providers can assume that subjects with communication disabilities are unable to understand and participate in complex treatment such as chemotherapy and they cannot tolerate chemotherapy-related side effects[27]. The rates of all treatments were lower among patients with brain and mental disabilities than among those without disabilities, possibly because treatment decisions are made by medical staff and caregivers without patient involvement[28]. Compared with subjects without disabilities, those with cardiopulmonary disabilities had lower and higher rates of surgery and radiotherapy, respectively, because of concerns about postoperative morbidity and mortality.

The lower treatment rates among subjects with disabilities may have several causes. First, physical, sensory, or communication challenges may prevent individuals with disabilities from accessing healthcare facilities and services. Lack of accessibility for patients in wheelchairs, inadequate provision for those with sensory impairments, or communication difficulties could hamper access to care[29,30]. Second, healthcare professionals and personnel may have unfavorable attitudes, prejudices, and preconceptions that restrict patients with disabilities from receiving healthcare[31]. These beliefs may result in unfair treatment or presumptions about the prospects and quality of life of people with disabilities. Third, the ability of healthcare professionals to handle the medical requirements of people with disabilities may be limited[32]. This may make it difficult to offer individuals with impairments suitable alternative treatments. Fourth, access to and quality of healthcare are typically limited for people with disabilities, reducing the likelihood of receiving all required treatments[33]. Socioeconomic variables, a lack of comprehensive insurance coverage, and deficient social support networks can affect these discrepancies[34]. Finally, patients with disabilities may have trouble expressing their medical requirements, preferences, and treatment objectives[35]. This may result in poor or no treatment as a result of miscommunication or misunderstanding. To address these issues, a concerted effort is needed to increase access to healthcare, strengthen training in the provision of care to people with disabilities, and promote an equitable healthcare system. It is critical that patients with disabilities have equitable access to treatments and that medical professionals receive adequate training in the care of such patients.

In this study, the overall mortality rate was higher in CRC patients with disabilities (aHR: 1.24), particularly those with severe disabilities (aHR: 1.57), than in those without disabilities. The disparities were especially apparent among patients with internal organ disabilities (aHR: 2.43), mental impairment (aHR: 2.23), or brain impairment (aHR: 1.95). Because most deaths in this study were caused by CRC, the overall mortality and CRC mortality rates were similar. This may be because of a high rate of complications or bad health behaviors, lower rate of intensive treatment (e.g., less surgery and reduced doses of chemotherapeutics or radiation), lower rate of intensive care, poor self-management or compliance, and poor social support or living conditions. Promotion of socioeconomic support, as well as training programs for the caregivers of patients with disabilities could reduce disparities in treatment outcomes.

The overall and CRC mortality rates of patients who underwent curative surgery were higher among those with disabilities (aHR: 1.23) and significantly higher among those with severe disabilities (aHR: 1.62). Patients with physical disabilities had a significantly higher mortality rate (aHR: 3.22), indicating a higher risk of surgery or surgery because of physical function limitations, postoperative self-care or rehabilitation, and less intensive adjuvant therapy. Patients with brain (aHR: 2.01) or mental (aHR: 2.02) disabilities had high mortality rates, indicating that an inadequate understanding of the disease and self-management and/or poorly focused adjuvant therapy can hamper postoperative care. Subjects with communication disabilities did not show disproportionate treatment results. Selection of the most appropriate surgical modality, postoperative treatment (e.g., pulmonary rehabilitation and self-treatment), and adjuvant treatment would reduce the treatment discrepancies between disabled and non-disabled patients with CRC.

This study had several limitations. First, it is unclear why some patients did not undergo diagnostic testing for staging or treatment (e.g., patient or family rejection, economic/transportation problems, or clinician judgment). Second, we did not have sufficient clinical information on preoperative function, treatment intensity (e.g., chemotherapy dose or radiotherapy frequency), or compliance with postoperative care and self-care. Third, the presence or absence of children or spouses in need of care could be variables, but in the data used in this study, there were no variables that could confirm this, so correction could not be made. In future studies, we will further examine the status of caring family members (children, spouse, etc.) as data and proceed with the study using propensity score matching.

In summary, patients with CRC with disabilities, particularly those with severe disabilities, were treated less aggressively compared with those without disabilities. Disability should not interfere with diagnosis and treatment in patients with CRC. Education for medical professionals and for disabled patients and their families is needed to overcome the perception that disability has a negative impact on the diagnosis and treatment of CRC. Further research is needed to develop guidelines to ensure equal diagnosis and treatment of CRC in disabled and non-disabled patients.

| 1. | Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration, Kocarnik JM, Compton K, Dean FE, Fu W, Gaw BL, Harvey JD, Henrikson HJ, Lu D, Pennini A, Xu R, Ababneh E, Abbasi-Kangevari M, Abbastabar H, Abd-Elsalam SM, Abdoli A, Abedi A, Abidi H, Abolhassani H, Adedeji IA, Adnani QES, Advani SM, Afzal MS, Aghaali M, Ahinkorah BO, Ahmad S, Ahmad T, Ahmadi A, Ahmadi S, Ahmed Rashid T, Ahmed Salih Y, Akalu GT, Aklilu A, Akram T, Akunna CJ, Al Hamad H, Alahdab F, Al-Aly Z, Ali S, Alimohamadi Y, Alipour V, Aljunid SM, Alkhayyat M, Almasi-Hashiani A, Almasri NA, Al-Maweri SAA, Almustanyir S, Alonso N, Alvis-Guzman N, Amu H, Anbesu EW, Ancuceanu R, Ansari F, Ansari-Moghaddam A, Antwi MH, Anvari D, Anyasodor AE, Aqeel M, Arabloo J, Arab-Zozani M, Aremu O, Ariffin H, Aripov T, Arshad M, Artaman A, Arulappan J, Asemi Z, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Ashraf T, Atorkey P, Aujayeb A, Ausloos M, Awedew AF, Ayala Quintanilla BP, Ayenew T, Azab MA, Azadnajafabad S, Azari Jafari A, Azarian G, Azzam AY, Badiye AD, Bahadory S, Baig AA, Baker JL, Balakrishnan S, Banach M, Bärnighausen TW, Barone-Adesi F, Barra F, Barrow A, Behzadifar M, Belgaumi UI, Bezabhe WMM, Bezabih YM, Bhagat DS, Bhagavathula AS, Bhardwaj N, Bhardwaj P, Bhaskar S, Bhattacharyya K, Bhojaraja VS, Bibi S, Bijani A, Biondi A, Bisignano C, Bjørge T, Bleyer A, Blyuss O, Bolarinwa OA, Bolla SR, Braithwaite D, Brar A, Brenner H, Bustamante-Teixeira MT, Butt NS, Butt ZA, Caetano Dos Santos FL, Cao Y, Carreras G, Catalá-López F, Cembranel F, Cerin E, Cernigliaro A, Chakinala RC, Chattu SK, Chattu VK, Chaturvedi P, Chimed-Ochir O, Cho DY, Christopher DJ, Chu DT, Chung MT, Conde J, Cortés S, Cortesi PA, Costa VM, Cunha AR, Dadras O, Dagnew AB, Dahlawi SMA, Dai X, Dandona L, Dandona R, Darwesh AM, das Neves J, De la Hoz FP, Demis AB, Denova-Gutiérrez E, Dhamnetiya D, Dhimal ML, Dhimal M, Dianatinasab M, Diaz D, Djalalinia S, Do HP, Doaei S, Dorostkar F, Dos Santos Figueiredo FW, Driscoll TR, Ebrahimi H, Eftekharzadeh S, El Tantawi M, El-Abid H, Elbarazi I, Elhabashy HR, Elhadi M, El-Jaafary SI, Eshrati B, Eskandarieh S, Esmaeilzadeh F, Etemadi A, Ezzikouri S, Faisaluddin M, Faraon EJA, Fares J, Farzadfar F, Feroze AH, Ferrero S, Ferro Desideri L, Filip I, Fischer F, Fisher JL, Foroutan M, Fukumoto T, Gaal PA, Gad MM, Gadanya MA, Gallus S, Gaspar Fonseca M, Getachew Obsa A, Ghafourifard M, Ghashghaee A, Ghith N, Gholamalizadeh M, Gilani SA, Ginindza TG, Gizaw ATT, Glasbey JC, Golechha M, Goleij P, Gomez RS, Gopalani SV, Gorini G, Goudarzi H, Grosso G, Gubari MIM, Guerra MR, Guha A, Gunasekera DS, Gupta B, Gupta VB, Gupta VK, Gutiérrez RA, Hafezi-Nejad N, Haider MR, Haj-Mirzaian A, Halwani R, Hamadeh RR, Hameed S, Hamidi S, Hanif A, Haque S, Harlianto NI, Haro JM, Hasaballah AI, Hassanipour S, Hay RJ, Hay SI, Hayat K, Heidari G, Heidari M, Herrera-Serna BY, Herteliu C, Hezam K, Holla R, Hossain MM, Hossain MBH, Hosseini MS, Hosseini M, Hosseinzadeh M, Hostiuc M, Hostiuc S, Househ M, Hsairi M, Huang J, Hugo FN, Hussain R, Hussein NR, Hwang BF, Iavicoli I, Ibitoye SE, Ida F, Ikuta KS, Ilesanmi OS, Ilic IM, Ilic MD, Irham LM, Islam JY, Islam RM, Islam SMS, Ismail NE, Isola G, Iwagami M, Jacob L, Jain V, Jakovljevic MB, Javaheri T, Jayaram S, Jazayeri SB, Jha RP, Jonas JB, Joo T, Joseph N, Joukar F, Jürisson M, Kabir A, Kahrizi D, Kalankesh LR, Kalhor R, Kaliyadan F, Kalkonde Y, Kamath A, Kameran Al-Salihi N, Kandel H, Kapoor N, Karch A, Kasa AS, Katikireddi SV, Kauppila JH, Kavetskyy T, Kebede SA, Keshavarz P, Keykhaei M, Khader YS, Khalilov R, Khan G, Khan M, Khan MN, Khan MAB, Khang YH, Khater AM, Khayamzadeh M, Kim GR, Kim YJ, Kisa A, Kisa S, Kissimova-Skarbek K, Kopec JA, Koteeswaran R, Koul PA, Koulmane Laxminarayana SL, Koyanagi A, Kucuk Bicer B, Kugbey N, Kumar GA, Kumar N, Kumar N, Kurmi OP, Kutluk T, La Vecchia C, Lami FH, Landires I, Lauriola P, Lee SW, Lee SWH, Lee WC, Lee YH, Leigh J, Leong E, Li J, Li MC, Liu X, Loureiro JA, Lunevicius R, Magdy Abd El Razek M, Majeed A, Makki A, Male S, Malik AA, Mansournia MA, Martini S, Masoumi SZ, Mathur P, McKee M, Mehrotra R, Mendoza W, Menezes RG, Mengesha EW, Mesregah MK, Mestrovic T, Miao Jonasson J, Miazgowski B, Miazgowski T, Michalek IM, Miller TR, Mirzaei H, Mirzaei HR, Misra S, Mithra P, Moghadaszadeh M, Mohammad KA, Mohammad Y, Mohammadi M, Mohammadi SM, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Mohammed S, Moka N, Mokdad AH, Molokhia M, Monasta L, Moni MA, Moosavi MA, Moradi Y, Moraga P, Morgado-da-Costa J, Morrison SD, Mosapour A, Mubarik S, Mwanri L, Nagarajan AJ, Nagaraju SP, Nagata C, Naimzada MD, Nangia V, Naqvi AA, Narasimha Swamy S, Ndejjo R, Nduaguba SO, Negoi I, Negru SM, Neupane Kandel S, Nguyen CT, Nguyen HLT, Niazi RK, Nnaji CA, Noor NM, Nuñez-Samudio V, Nzoputam CI, Oancea B, Ochir C, Odukoya OO, Ogbo FA, Olagunju AT, Olakunde BO, Omar E, Omar Bali A, Omonisi AEE, Ong S, Onwujekwe OE, Orru H, Ortega-Altamirano DV, Otstavnov N, Otstavnov SS, Owolabi MO, P A M, Padubidri JR, Pakshir K, Pana A, Panagiotakos D, Panda-Jonas S, Pardhan S, Park EC, Park EK, Pashazadeh Kan F, Patel HK, Patel JR, Pati S, Pattanshetty SM, Paudel U, Pereira DM, Pereira RB, Perianayagam A, Pillay JD, Pirouzpanah S, Pishgar F, Podder I, Postma MJ, Pourjafar H, Prashant A, Preotescu L, Rabiee M, Rabiee N, Radfar A, Radhakrishnan RA, Radhakrishnan V, Rafiee A, Rahim F, Rahimzadeh S, Rahman M, Rahman MA, Rahmani AM, Rajai N, Rajesh A, Rakovac I, Ram P, Ramezanzadeh K, Ranabhat K, Ranasinghe P, Rao CR, Rao SJ, Rawassizadeh R, Razeghinia MS, Renzaho AMN, Rezaei N, Rezaei N, Rezapour A, Roberts TJ, Rodriguez JAB, Rohloff P, Romoli M, Ronfani L, Roshandel G, Rwegerera GM, S M, Sabour S, Saddik B, Saeed U, Sahebkar A, Sahoo H, Salehi S, Salem MR, Salimzadeh H, Samaei M, Samy AM, Sanabria J, Sankararaman S, Santric-Milicevic MM, Sardiwalla Y, Sarveazad A, Sathian B, Sawhney M, Saylan M, Schneider IJC, Sekerija M, Seylani A, Shafaat O, Shaghaghi Z, Shaikh MA, Shamsoddin E, Shannawaz M, Sharma R, Sheikh A, Sheikhbahaei S, Shetty A, Shetty JK, Shetty PH, Shibuya K, Shirkoohi R, Shivakumar KM, Shivarov V, Siabani S, Siddappa Malleshappa SK, Silva DAS, Singh JA, Sintayehu Y, Skryabin VY, Skryabina AA, Soeberg MJ, Sofi-Mahmudi A, Sotoudeh H, Steiropoulos P, Straif K, Subedi R, Sufiyan MB, Sultan I, Sultana S, Sur D, Szerencsés V, Szócska M, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Tabuchi T, Tadbiri H, Taherkhani A, Takahashi K, Talaat IM, Tan KK, Tat VY, Tedla BAA, Tefera YG, Tehrani-Banihashemi A, Temsah MH, Tesfay FH, Tessema GA, Thapar R, Thavamani A, Thoguluva Chandrasekar V, Thomas N, Tohidinik HR, Touvier M, Tovani-Palone MR, Traini E, Tran BX, Tran KB, Tran MTN, Tripathy JP, Tusa BS, Ullah I, Ullah S, Umapathi KK, Unnikrishnan B, Upadhyay E, Vacante M, Vaezi M, Valadan Tahbaz S, Velazquez DZ, Veroux M, Violante FS, Vlassov V, Vo B, Volovici V, Vu GT, Waheed Y, Wamai RG, Ward P, Wen YF, Westerman R, Winkler AS, Yadav L, Yahyazadeh Jabbari SH, Yang L, Yaya S, Yazie TSY, Yeshaw Y, Yonemoto N, Younis MZ, Yousefi Z, Yu C, Yuce D, Yunusa I, Zadnik V, Zare F, Zastrozhin MS, Zastrozhina A, Zhang J, Zhong C, Zhou L, Zhu C, Ziapour A, Zimmermann IR, Fitzmaurice C, Murray CJL, Force LM. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:420-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1180] [Cited by in RCA: 1116] [Article Influence: 372.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kang MJ, Won YJ, Lee JJ, Jung KW, Kim HJ, Kong HJ, Im JS, Seo HG; Community of Population-Based Regional Cancer Registries. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2019. Cancer Res Treat. 2022;54:330-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 71.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64229] [Article Influence: 16057.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (174)] |

| 4. | Onyoh EF, Hsu WF, Chang LC, Lee YC, Wu MS, Chiu HM. The Rise of Colorectal Cancer in Asia: Epidemiology, Screening, and Management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim SE, Paik HY, Yoon H, Lee JE, Kim N, Sung MK. Sex- and gender-specific disparities in colorectal cancer risk. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5167-5175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 6. | Hossain MS, Karuniawati H, Jairoun AA, Urbi Z, Ooi J, John A, Lim YC, Kibria KMK, Mohiuddin AKM, Ming LC, Goh KW, Hadi MA. Colorectal Cancer: A Review of Carcinogenesis, Global Epidemiology, Current Challenges, Risk Factors, Preventive and Treatment Strategies. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 463] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 135.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394:1467-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1570] [Cited by in RCA: 2985] [Article Influence: 497.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Patel A, Gantz O, Zagadailov P, Merchant AM. The role of socioeconomic disparity in colorectal cancer stage at presentation. Updates Surg. 2019;71:523-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Iezzoni LI, Kurtz SG, Rao SR. Trends in colorectal cancer screening over time for persons with and without chronic disability. Disabil Health J. 2016;9:498-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McCarthy EP, Ngo LH, Roetzheim RG, Chirikos TN, Li D, Drews RE, Iezzoni LI. Disparities in breast cancer treatment and survival for women with disabilities. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:637-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McCarthy EP, Ngo LH, Chirikos TN, Roetzheim RG, Li D, Drews RE, Iezzoni LI. Cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among persons with Social Security Disability Insurance on Medicare. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:611-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Deroche CB, McDermott SW, Mann JR, Hardin JW. Colorectal Cancer Screening Adherence in Selected Disabilities Over 10 Years. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:735-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Willis D, Samalin E, Satgé D. Colorectal Cancer in People with Intellectual Disabilities. Oncology. 2018;95:323-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shin DW, Chang D, Jung JH, Han K, Kim SY, Choi KS, Lee WC, Park JH, Park JH. Disparities in the Participation Rate of Colorectal Cancer Screening by Fecal Occult Blood Test among People with Disabilities: A National Database Study in South Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52:60-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gofine M, Mielenz TJ, Vasan S, Lebwohl B. Use of Colorectal Cancer Screening Among People With Mobility Disability. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52:789-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shin DW, Park J, Yeob KE, Yoon SJ, Jang SN, Kim SY, Park JH, Park JH, Kawachi I. Disparities in prostate cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survival among men with disabilities: Retrospective cohort study in South Korea. Disabil Health J. 2021;14:101125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim M, Jung W, Kim SY, Park JH, Shin DW. The Korea National Disability Registration System. Epidemiol Health. 2023;45:e2023053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee H, Cho J, Shin DW, Lee SP, Hwang SS, Oh J, Yang HK, Hwang SH, Son KY, Chun SH, Cho B, Guallar E. Association of cardiovascular health screening with mortality, clinical outcomes, and health care cost: a nationwide cohort study. Prev Med. 2015;70:19-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shin DW, Cho B, Guallar E. Korean National Health Insurance Database. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shin DW, Lee JW, Jung JH, Han K, Kim SY, Choi KS, Park JH, Park JH. Disparities in Cervical Cancer Screening Among Women With Disabilities: A National Database Study in South Korea. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2778-2786. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Cheol Seong S, Kim YY, Khang YH, Heon Park J, Kang HJ, Lee H, Do CH, Song JS, Hyon Bang J, Ha S, Lee EJ, Ae Shin S. Data Resource Profile: The National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:799-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 609] [Article Influence: 87.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee J, Lee JS, Park SH, Shin SA, Kim K. Cohort Profile: The National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC), South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 729] [Article Influence: 104.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ministry of Health and Welfare. Criteria for the disability grading (Korean). 2019. [cited 31 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.mohw.go.kr/eng/. |

| 24. | Shin DW, Cho JH, Noh JM, Han H, Han K, Park SH, Kim SY, Park JH, Park JH, Kawachi I. Disparities in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Lung Cancer among People with Disabilities. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:163-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nuttall M, van der Meulen J, Emberton M. Charlson scores based on ICD-10 administrative data were valid in assessing comorbidity in patients undergoing urological cancer surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:265-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim KE, Lee YJ, Lee JY, Jeong WK, Baek SK, Bae SU. Minimally invasive treatments for early colorectal cancer: comparison of endoscopic resection and laparoscopic surgery. Korean J Clin Oncol. 2022;18:47-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kwon J, Kim SY, Yeob KE, Han HS, Lee KH, Shin DW, Kim YY, Park JH, Park JH, Kawachi I. Differences in diagnosis, treatment, and survival rate of acute myeloid leukemia with or without disabilities: A national cohort study in the Republic of Korea. Cancer Med. 2020;9:5335-5344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sue K, Mazzotta P, Grier E. Palliative care for patients with communication and cognitive difficulties. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65:S19-S24. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Withers J, Speight C. Health Care for Individuals with Hearing Loss or Vision Loss: A Minefield of Barriers to Accessibility. N C Med J. 2017;78:107-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bailey R, Willner P, Dymond S. A visual aid to decision-making for people with intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:37-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | VanPuymbrouck L, Friedman C, Feldner H. Explicit and implicit disability attitudes of healthcare providers. Rehabil Psychol. 2020;65:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Satchidanand N, Gunukula SK, Lam WY, McGuigan D, New I, Symons AB, Withiam-Leitch M, Akl EA. Attitudes of healthcare students and professionals toward patients with physical disability: a systematic review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91:533-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Meade MA, Mahmoudi E, Lee SY. The intersection of disability and healthcare disparities: a conceptual framework. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:632-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Dorner TE, Mittendorfer-Rutz E. Socioeconomic inequalities in treatment of individuals with common mental disorders regarding subsequent development of mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:1015-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Agaronnik N, Campbell EG, Ressalam J, Iezzoni LI. Communicating with Patients with Disability: Perspectives of Practicing Physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1139-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |