Published online May 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i5.1833

Peer-review started: December 3, 2023

First decision: January 15, 2024

Revised: January 25, 2024

Accepted: February 18, 2024

Article in press: February 18, 2024

Published online: May 15, 2024

Processing time: 158 Days and 5.7 Hours

Although the benefits of antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have been proven, researchers have not con

To investigate the efficacy of perioperative remedial antiviral therapy in patients with HBV-related HCC.

A retrospective study of patients who underwent radical resection for HBV-related HCC at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University from January 2016 to June 2019 was conducted. Considering the history of antiviral therapy, patients were assigned to remedial antiviral therapy and preoperative antiviral therapy groups.

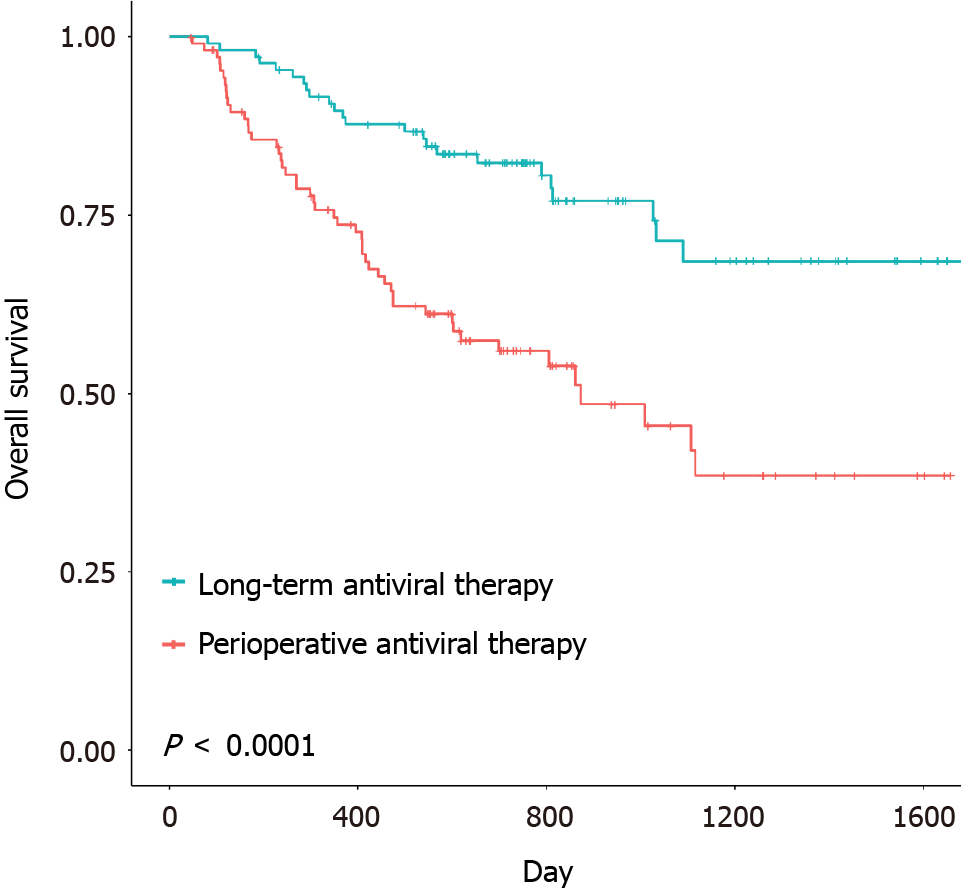

Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed significant differences in overall survival (P < 0.0001) and disease-free survival (P = 0.035) between the two groups. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that a history of preoperative antiviral treatment was independently related to improved survival (hazard ratio = 0.27; 95% confidence interval: 0.08-0.88; P = 0.030).

In patients with HBV-related HCC, it is ideal to receive preoperative long-term antiviral therapy, which helps patients tolerate more extensive hepatectomy; however, remedial antiviral therapy, which reduces preoperative HBV-DNA levels to less than 4 Log10 copies DNA/mL, can also result in improved outcomes.

Core Tip: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the seventh most common cancer in the world and is usually associated with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Radical resection and antiviral therapy are considered key clinical treatments for patients with HBV-related HCC. However, many patients have their HCC and HBV infection detected at the same time, so they receive remedial antiviral treatment beginning in the perioperative period, missing the opportunity for long-term preope

- Citation: Mu F, Hu LS, Xu K, Zhao Z, Yang BC, Wang YM, Guo K, Shi JH, Lv Y, Wang B. Perioperative remedial antiviral therapy in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma resection: How to achieve a better outcome. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(5): 1833-1848

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i5/1833.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i5.1833

Primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common malignancy worldwide and the fourth most common cause of cancer-related death[1]. Approximately half of newly diagnosed HCC cases in the world occur in China, and hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related HCC comprises the majority of cases[2]. Antiviral therapy can reduce the risk of HCC in patients with chronic hepatitis B[3], it also reduces the risk of postoperative viral reactivation and liver failure in patients undergoing radical resection for HBV-related HCC[4,5]. Previous prospective studies and meta-analyses have suggested that preoperative antiviral therapy for HBV-related HCC patients who have not received antiviral therapy has potential benefits on tumor recurrence and long-term survival after radical resection[6,7]. However, the difference in prognosis between preoperative long-term and remedial perioperative antiviral therapy for HBV-related HCC radical resection remains unclear. This retrospective study was designed to compare the effects of preoperative long-term vs. radical perioperative antiviral therapy on tumor recurrence and long-term survival after radical resection for HBV-related HCC patients.

This was a retrospective cohort study of HCC patients who underwent radical resection of HCC at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University from January 2016 to June 2019. The clinical data of these patients, including demographic features, perioperative laboratory values, surgical information, and pathological data, were collected from electronic medical records. HCC was diagnosed based on histopathology of the excised specimens. Patients who met the following inclusion criteria were enrolled: (1) Aged 18-70 years; (2) Initial resection; (3) Positive hepatitis B surface antigen results and negative results for antibodies against hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus; (4) No antitumor treatment, such as transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation-chemotherapy or radiotherapy; (5) No postoperative liver transplantation; (6) Barcelona Clinic HCC stage 0, A, or B (a few patients with stage C disease were also enrolled); (7) Negative resection margin; and (8) No other tumors. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiao Tong University, and the approval number of the institutional review board is No. XJTU1AF2021LSK-414. The study followed the standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiao Tong University. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (registry number NCT05406089).

Before resection, all patients with HCC in our hospital underwent examination for HBV infection indicators, and the results were evaluated to determine whether antiviral therapy should be administered. Preoperative long-term antiviral therapy was defined as regular antiviral treatment for at least 24 wk before radical resection (antiviral therapy continued during the perioperative period); remedial perioperative antiviral therapy was defined as initial antiviral therapy since the perioperative period of radical resection, it was received by patients who were diagnosed with HCC and whose HBV infection was first detected at the same time. For the preoperative long-term antiviral therapy group, previous antiviral treatments consisted of adefovir, entecavir, and lamivudine, all of which were given alone or in combination according to the physicians’ advice. The antivirals were distributed, and this process was supervised by dedicated personnel during hospitalization. After discharge, patients in both groups still received sustained antiviral therapy and follow-up monitoring, and patients were switched to other antiviral drugs if they developed resistance.

Intermittent interruption of the portal hepatis was adopted for hepatic inflow occlusion. The type of radical resection was defined as follows based on the removal range and difficulty of operation according to the research of Kawaguchi[8,9]: (1) Wedge hepatectomy for anterolateral or posterosuperior segment and left lateral sectionectomy; (2) Anterolateral segmentectomy and left hepatectomy; and (3) Posterosuperior segmentectomy, right posterior sectionectomy, right hepatectomy, central hepatectomy and extended left/right hepatectomy. The histologic grade of the resected tumor was classified as good, moderate, or poor differentiation. The maximal diameter of the tumor was considered to be the tumor size. We also evaluated the presence of capsulation, vascular invasion, and microsatellite lesions in the resected tumor as well as the degree of cirrhosis in the noncancerous tissue.

After surgery for HCC, all patients were followed up regularly in the outpatient clinic; the follow-up included monthly ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at an interval of 6 months. Tumor recurrence was suspected if progressively worsening abdominal symptoms occurred, the serum alpha-fetoprotein level became elevated, or imaging evidence indicated a new hepatic lesion (intrahepatic or extrahepatic). Recurrence was diagnosed based on new radiologically evident lesions by CT, MRI, and hepatic arteriography. Patients with tumor recurrence usually received chemotherapy, radiotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, or transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, and these follow-up treatments were based on the general condition of the patient and extent of the tumor.

Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to reduce the effect of confounding factors on prognosis between the two groups through the R project (r-project.org/). All the data were analyzed using SPSS version 16.0 (Chicago, IL, United States). The variable data are expressed as the mean and standard deviation or the median and range. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were compared using the independent-sample t test. Disease-free and overall survival rates were calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences in survival between groups were compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate regression analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazard model. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Significant variables in the univariate analysis were further included stepwise in the multivariate analysis.

During the study period, 494 patients underwent radical resection at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. Patients without HBV infection (n = 74), those who had hepatitis C virus infection (n = 20), those who received treatment for less than half a year (n = 78), those who failed to follow prescribed medication or stopped medication before hospitalization (n = 27), those who underwent postoperative liver transplantation (n = 6), those whose condition was complicated by other tumors (n = 2), and those who had received other treatment prior to radical resection of HCC (n = 12) were excluded from the study. A total of 275 patients met the inclusion criteria, including 154 in the preoperative long-term antiviral therapy group and 121 in the remedial perioperative antiviral therapy group. A total of 108 pairs of patients were ultimately included in the PSM analysis.

The characteristics of the 216 patients who received remedial perioperative antiviral therapy or preoperative long-term antiviral therapy are presented in Table 1. Patients in the remedial perioperative antiviral therapy group had significantly higher alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin and HBV-DNA levels (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Remedial perioperative antiviral therapy group (n = 108) | Preoperative long-term antiviral therapy group (n = 108) | P value |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Antiviral treatment | < 0.001 | ||

| Perioperative | 108 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Long-term | 0 (0.0) | 108 (100.0) | |

| Sex | 0.705 | ||

| Male | 90 (83.3) | 93 (86.1) | |

| Female | 18 (16.7) | 15 (13.9) | |

| Age | 0.067 | ||

| ≤ 60 yr | 85 (78.7) | 72 (66.7) | |

| > 60 yr | 23 (21.3) | 36 (33.3) | |

| Treatment after resection | 0.907 | ||

| TACE | 31 (70.5) | 32 (68.1) | |

| RFA | 5 (11.4) | 6 (12.8) | |

| TACE and RFA | 4 (9.1) | 6 (12.8) | |

| Radio/chemo | 4 (9.1) | 3 (6.4) | |

| Preoperative laboratory tests | |||

| ALT | 0.001 | ||

| ≤ 40 IU/L | 48 (44.4) | 72 (67.3) | |

| > 40 IU/L | 60 (55.6) | 35 (32.7) | |

| AST | 0.001 | ||

| ≤ 35 IU/L | 38 (35.2) | 64 (59.8) | |

| > 35 IU/L | 70 (64.8) | 43 (40.2) | |

| HBeAg | 1.000 | ||

| Negative | 74 (68.5) | 75 (69.4) | |

| Positive | 34 (31.5) | 33 (30.6) | |

| Hemoglobin | 0.885 | ||

| ≤ 130 g/L | 35 (32.4) | 37 (34.3) | |

| > 130 g/L | 73 (67.6) | 71 (65.7) | |

| Creatinine | 1.000 | ||

| ≤ 97 μmol/L | 107 (99.1) | 106 (98.1) | |

| > 97 μmol/L | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Platelets | 0.164 | ||

| ≤ 120 × 109/L | 37 (34.3) | 48 (44.4) | |

| > 120 × 109/L | 71 (65.7) | 60 (55.6) | |

| Leukocytes | 1.000 | ||

| ≤ 9.5 × 109/L | 101 (93.5) | 102 (94.4) | |

| > 9.5 × 109/L | 7 (6.5) | 6 (5.6) | |

| NEUT | 0.503 | ||

| ≤ 75% | 83 (76.9) | 88 (81.5) | |

| > 75% | 25 (23.1) | 20 (18.5) | |

| Bilirubin | 0.041 | ||

| ≤ 17 μmol/L | 48 (44.4) | 64 (59.8) | |

| > 17 μmol/L | 60 (55.6) | 44 (40.7) | |

| Albumin | 0.259 | ||

| ≤ 35 g/L | 29 (26.9) | 21 (19.4) | |

| > 35 g/L | 79 (73.1) | 87 (80.6) | |

| Prothrombin time | 0.592 | ||

| ≤ 13 s | 9 (8.3) | 6 (5.6) | |

| > 13 s | 99 (91.7) | 102 (94.4) | |

| International normalized ratio | 0.378 | ||

| ≤ 1.3 | 94 (87.0) | 99 (91.7) | |

| > 1.3 | 14 (13.0) | 9 (8.3) | |

| Alpha fetoprotein | 0.187 | ||

| ≤ 400 ng/mL | 70 (47.8) | 79 (79.3) | |

| > 400 ng/mL | 38 (52.2) | 29 (20.7) | |

| HBV-DNA level | < 0.001 | ||

| ≤ 10000 copies/mL | 49 (52.7) | 75 (96.2) | |

| > 10000 copies/mL | 44 (47.3) | 3 (3.8) | |

| Operation information | |||

| Type of operation | 0.192 | ||

| I (low range) | 49 (45.4) | 59 (55.1) | |

| II (middle range) | 15 (13.9) | 17 (15.9) | |

| III (high range) | 44 (40.7) | 31 (29.0) | |

| Liver fibrosis | 0.381 | ||

| No | 23 (21.3) | 17 (15.7) | |

| Yes | 85 (78.7) | 91 (84.3) | |

| Operation time | 0.674 | ||

| ≤ 3 h | 39 (36.1) | 43 (39.8) | |

| > 3 h | 69 (63.9) | 65 (60.2) | |

| Blood loss | 0.055 | ||

| ≤ 400 mL | 26 (32.1) | 35 (48.6) | |

| > 400 mL | 55 (67.9) | 37 (51.4) | |

| Resection margins | 0.388 | ||

| ≤ 1 cm | 75 (73.5) | 82 (79.6) | |

| > 1 cm | 27 (26.5) | 21 (20.4) | |

| Tumor information | |||

| Capsular invasion | 0.116 | ||

| No | 28 (26.2) | 40 (37.4) | |

| Yes | 78 (72.9) | 67 (62.6) | |

| Tumor diameter | 0.339 | ||

| ≤ 5 cm | 57 (52.8) | 64 (59.3) | |

| > 5 cm | 51 (47.2) | 44 (40.7) | |

| Tumor number | 0.879 | ||

| Single | 97 (89.8) | 101 (93.5) | |

| Numerous | 11 (10.2) | 7 (6.5) | |

| BCLC stage | 0.051 | ||

| O | 6 (5.6) | 18 (16.7) | |

| A | 87 (80.6) | 78 (72.2) | |

| B | 5 (4.6) | 2 (1.9) | |

| C | 10 (9.3) | 10 (9.3) | |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.168 | ||

| Poor | 32 (30.5) | 21 (19.6) | |

| Moderate | 70 (66.7) | 81 (75.7) | |

| High | 3 (2.9) | 5 (4.7) | |

| Portal vein invasion | 1.000 | ||

| No | 98 (90.7) | 98 (90.7) | |

| Yes | 10 (9.3) | 10 (9.3) | |

| MVI | 0.090 | ||

| 0 | 39 (36.1) | 52 (48.1) | |

| 1 | 34 (31.5) | 34 (31.5) | |

| 2 | 35 (32.4) | 22 (20.4) | |

| Satellite lesions | 0.378 | ||

| No | 94 (87.0) | 99 (91.7) | |

| Yes | 14 (13.0) | 9 (8.3) |

The disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were 14.9 months (range: 1.0-53.4 months) and 19.7 months (range: 1.6-55.3 months), respectively, in the remedial perioperative antiviral therapy group and 20.1 months (range: 1.1-57.5 months) and 27.2 months (range: 2.7-57.5 months), respectively, in the preoperative long-term antiviral therapy group. The DFS and OS of the two groups are shown in Figures 1 and 2. Significant differences in OS (P < 0.0001) and DFS (P = 0.035) were identified between the two groups. The median DFS and OS of patients in the remedial perioperative antiviral therapy group (n = 108) were 10.6 and 18.7 months, respectively, and these durations were extended to 19.2 and 25.0 months, respectively, in the preoperative long-term antiviral therapy group (n = 108). In the remedial perioperative and preoperative long-term antiviral therapy groups, the 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS rates were 73.7%, 56.0%, 45.5% and 89.7%, 82.3%, and 68.5%, respectively, while the 1-, 2-, and 3-year DFS rates were 52.7%, 39.7%, 28.9% and 62.8%, 51.4%, and 46.8%, respectively.

Univariate and multivariate analyses for the prognostic factors of OS and DFS are shown below (Table 2). Multivariate analyses revealed that the type of operation, capsular invasion, tumor number, tumor differentiation, portal vein invasion, and preoperative long-term antiviral treatment were independently associated with OS. Notably, preoperative long-term antiviral treatment was confirmed to be independently related to improved survival outcomes [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.27; 95% confidence interval: 0.08-0.88; P = 0.030]. Multivariate analyses revealed that only MVI and satellite lesions were independently associated with DFS, whereas preoperative long-term antiviral treatment was not associated with DFS.

| Factors | No. of patients | Overall survival | Disease-free survival | ||||||||||

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||||||

| HR | (95%CI) | P value | HR | (95%CI) | P value | HR | (95%CI) | P value | HR | (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Antiviral treatment | 0.370 | 0.22-0.6 | < 0.001 | 0.270 | 0.08-0.88 | 0.030 | 0.680 | 0.47-0.98 | 0.036 | 1.160 | 0.66-2.04 | 0.609 | |

| Perioperative | 108 (50.0) | ||||||||||||

| Long-term | 108 (50.0) | ||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.930 | 0.49-1.76 | 0.820 | 1.260 | 0.73-2.16 | 0.408 | |||||||

| Male | 183 (84.7) | ||||||||||||

| Female | 33 (15.3) | ||||||||||||

| Age | 1.080 | 0.65-1.8 | 0.753 | 0.820 | 0.54-1.24 | 0.338 | |||||||

| ≤ 60 yr | 157 (72.7) | ||||||||||||

| > 60 yr | 59 (27.3) | ||||||||||||

| Treatment after resection | 0.750 | 0.5-1.13 | 0.165 | 0.890 | 0.7-1.13 | 0.331 | |||||||

| TACE | 63 (69.2) | ||||||||||||

| RFA | 11 (12.1) | ||||||||||||

| TACE and RFA | 10 (11.0) | ||||||||||||

| Radio/chemo | 7 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| ALT | 1.730 | 1.09-2.75 | 0.019 | 2.360 | 0.88-6.31 | 0.088 | 1.230 | 0.86-1.77 | 0.261 | ||||

| ≤ 40 IU/L | 120 (55.8) | ||||||||||||

| > 40 IU/L | 95 (44.2) | ||||||||||||

| AST | 2.470 | 1.51-4.05 | < 0.001 | 0.250 | 0.08-0.84 | 0.244 | 1.730 | 1.19-2.5 | 0.004 | 0.720 | 0.41-1.25 | 0.239 | |

| ≤ 35 IU/L | 102 (47.4) | ||||||||||||

| > 35 IU/L | 113 (52.6) | ||||||||||||

| HBeAg | 1.720 | 1.08-2.76 | 0.023 | 1.530 | 0.62-3.77 | 0.357 | 1.170 | 0.8-1.71 | 0.425 | ||||

| Negative | 149 (69.0) | ||||||||||||

| Positive | 67 (31.0) | ||||||||||||

| Hemoglobin | 1.180 | 0.72-1.94 | 0.518 | 1.460 | 0.98-2.18 | 0.066 | |||||||

| ≤ 130 g/L | 74 (34.3) | ||||||||||||

| > 130 g/L | 144 (65.7) | ||||||||||||

| Creatinine | 0.860 | 0.12-6.17 | 0.877 | 1.280 | 0.32-5.18 | 0.730 | |||||||

| ≤ 97 μmol/L | 215 (98.6) | ||||||||||||

| > 97 μmol/L | 3 (1.4) | ||||||||||||

| Platelets | 1.040 | 0.65-1.66 | 0.870 | 1.280 | 0.88-1.86 | 0.195 | |||||||

| ≤ 120 × 109/L | 85 (39.4) | ||||||||||||

| > 120 × 109/L | 131 (60.5) | ||||||||||||

| Leukocytes | 1.440 | 0.63-3.33 | 0.390 | 1.390 | 0.68-2.85 | 0.370 | |||||||

| ≤ 9.5 × 109/L | 203 (94.0) | ||||||||||||

| > 9.5 × 109/L | 13 (6.0) | ||||||||||||

| Neutrophils | 1.110 | 0.64-1.9 | 0.716 | 1.060 | 0.69-1.64 | 0.782 | |||||||

| ≤ 75% | 171 (79.2) | ||||||||||||

| > 75% | 45 (20.8) | ||||||||||||

| Bilirubin | 2.040 | 1.27-3.27 | 0.003 | 2.010 | 0.82-4.93 | 0.127 | 1.270 | 0.88-1.82 | 0.197 | ||||

| ≤ 17 μmol/L | 112 (51.9) | ||||||||||||

| > 17 μmol/L | 104 (48.1) | ||||||||||||

| Albumin | 0.820 | 0.48-1.38 | 0.450 | 1.340 | 0.85-2.1 | 0.203 | |||||||

| ≤ 35 g/L | 50 (23.1) | ||||||||||||

| > 35 g/L | 166 (76.9) | ||||||||||||

| Prothrombin time | 1.190 | 0.48-2.95 | 0.707 | 0.980 | 0.48-2.01 | 0.955 | |||||||

| ≤ 13 s | 13 (6.0) | ||||||||||||

| > 13 s | 203 (94.0) | ||||||||||||

| International normalized ratio | 1.670 | 0.86-3.27 | 0.131 | 1.180 | 0.66-2.1 | 0.575 | |||||||

| ≤ 1.3 | 193 (89.4) | ||||||||||||

| > 1.3 | 23 (10.6) | ||||||||||||

| Alpha fetoprotein | 3.050 | 1.85-5.02 | < 0.001 | 0.620 | 0.22-1.69 | 0.348 | 2.320 | 1.56-3.44 | 0.000 | 0.920 | 0.51-1.66 | 0.790 | |

| ≤ 400 μg/L | 149 (69.0) | ||||||||||||

| > 400 μg/L | 67 (31.0) | ||||||||||||

| HBV-DNA level | 3.060 | 1.84-5.1 | < 0.001 | 1.940 | 0.67-5.61 | 0.221 | 1.440 | 0.94-2.19 | 0.091 | ||||

| ≤ 10000 copies/mL | 124 (72.5) | ||||||||||||

| > 10000 copies/mL | 47 (27.5) | ||||||||||||

| Operation information | |||||||||||||

| Type | 2.560 | 1.58-4.15 | 0.000 | 2.820 | 1-7.92 | 0.049 | 1.830 | 1.27-2.64 | 0.001 | 1.050 | 0.56-1.96 | 0.882 | |

| I (low range) | 108 (50.2) | ||||||||||||

| II (middle range) | 32 (14.9) | ||||||||||||

| III (high range) | 75 (34.9) | ||||||||||||

| Liver fibrosis | 0.610 | 0.36-1.05 | 0.073 | 0.800 | 0.52-1.25 | 0.326 | |||||||

| No | 40 (18.5) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 176 (81.5) | ||||||||||||

| Operation time | 1.630 | 0.99-2.68 | 0.054 | 1.490 | 1.01-2.18 | 0.044 | 1.280 | 0.65-2.51 | 0.475 | ||||

| ≤ 3 h | 82 (38.0) | ||||||||||||

| > 3 h | 134 (62.0) | ||||||||||||

| Blood loss | 2.350 | 1.25-4.42 | 0.008 | 1.560 | 0.55-4.42 | 0.402 | 1.930 | 1.21-3.07 | 0.006 | 1.590 | 0.85-2.99 | 0.147 | |

| ≤ 400 mL | 61 (39.9) | ||||||||||||

| > 400 mL | 92 (60.1) | ||||||||||||

| Resection Margins | 0.930 | 0.53-1.62 | 0.796 | 0.800 | 0.51-1.26 | 0.344 | |||||||

| ≤ 1 | 157 (75.8) | ||||||||||||

| > 1 | 50 (24.2) | ||||||||||||

| Tumor information | |||||||||||||

| Capsular invasion | 4.350 | 2.21-8.54 | < 0.001 | 9.560 | 2.45-37.28 | 0.001 | 2.710 | 1.71-4.29 | 0.000 | 1.540 | 0.81-2.94 | 0.185 | |

| No | 68 (31.9) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 145 (68.1) | ||||||||||||

| Tumor diameter | 4.110 | 2.5-6.75 | < 0.001 | 1.010 | 0.31-3.33 | 0.983 | 2.750 | 1.91-3.98 | 0.000 | 1.550 | 0.77-3.13 | 0.217 | |

| ≤ 5 cm | 121 (56.0) | ||||||||||||

| > 5 cm | 95 (44.0) | ||||||||||||

| Tumor number | 1.680 | 1.24-2.27 | < 0.001 | 2.640 | 1.32-5.27 | 0.006 | 1.690 | 1.21-2.38 | 0.002 | 1.260 | 0.74-2.16 | 0.400 | |

| Single | 198 (91.7) | ||||||||||||

| Numerous | 18 (8.3) | ||||||||||||

| BCLC stage | 4.930 | 2.94-8.29 | < 0.001 | 0.710 | 0.12-4.28 | 0.706 | 4.320 | 2.75-6.78 | 0.000 | 2.480 | 0.56-10.93 | 0.230 | |

| O | 24 (11.1) | ||||||||||||

| A | 165 (76.4) | ||||||||||||

| B | 7 (3.2) | ||||||||||||

| C | 20 (9.3) | ||||||||||||

| Tumor differentiation | 0.400 | 0.25-0.64 | < 0.001 | 0.130 | 0.05-0.32 | 0.000 | 0.670 | 0.45-1 | 0.051 | ||||

| Poor | 53 (25.0) | ||||||||||||

| Moderate | 151 (71.2) | ||||||||||||

| High | 8 (3.8) | ||||||||||||

| Portal vein invasion | 5.130 | 2.84-9.26 | < 0.001 | 22.850 | 2.09-249.85 | 0.010 | 4.590 | 2.78-7.59 | 0.000 | 1.230 | 0.24-6.37 | 0.803 | |

| No | 196 (90.7) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 20 (9.3) | ||||||||||||

| MVI | 2.550 | 1.52-4.28 | < 0.001 | 1.740 | 0.62-4.88 | 0.291 | 2.240 | 1.51-3.32 | 0.000 | 2.110 | 1.07-4.19 | 0.032 | |

| 0 | 91 (42.1) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 68 (31.5) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 57 (26.4) | ||||||||||||

| Satellite lesions | 2.150 | 1.13-4.09 | 0.020 | 2.130 | 0.56-8.16 | 0.268 | 3.080 | 1.87-5.08 | 0.000 | 2.330 | 1.09-4.95 | 0.028 | |

| No | 193 (10.6) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 23 (89.4) | ||||||||||||

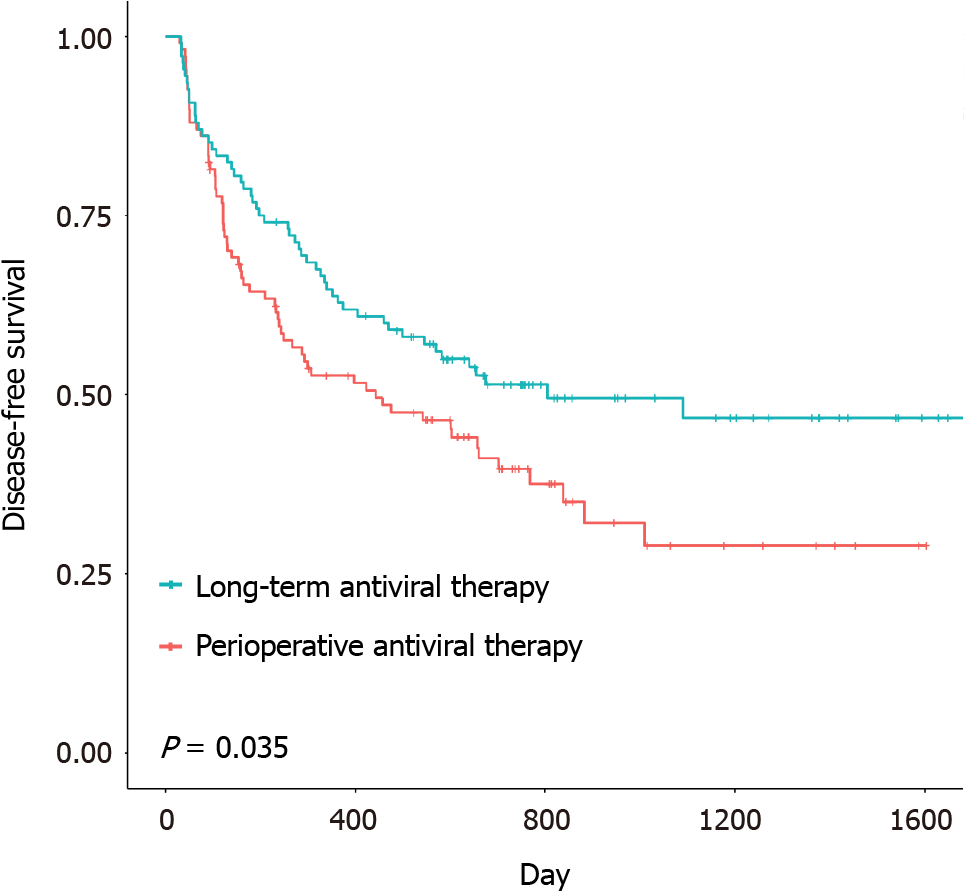

We compared DFS and OS between patients with different HBV-DNA levels in the two groups above, focusing on 4 Log10 copies/mL as the cutoff for HBV-DNA in the remedial perioperative antiviral therapy group and 2 Log10 copies/mL as the cutoff for HBV-DNA in the preoperative long-term antiviral therapy group (a few patients had HBV-DNA concentrations higher than 4 Log10 copies/mL[10]). The DFS and OS curves of the subgroups are shown in Figure 3. No significant differences were observed between the subgroups in the preoperative long-term antiviral therapy group (P value for OS = 0.97; P value for DFS = 0.46). However, when comparing patients with HBV-DNA levels higher or less than 4 Log10 copies/mL in the remedial perioperative antiviral therapy group, the log-rank test showed a significant difference (P value of OS was 0.0011), with a P value of 0.46 for DFS.

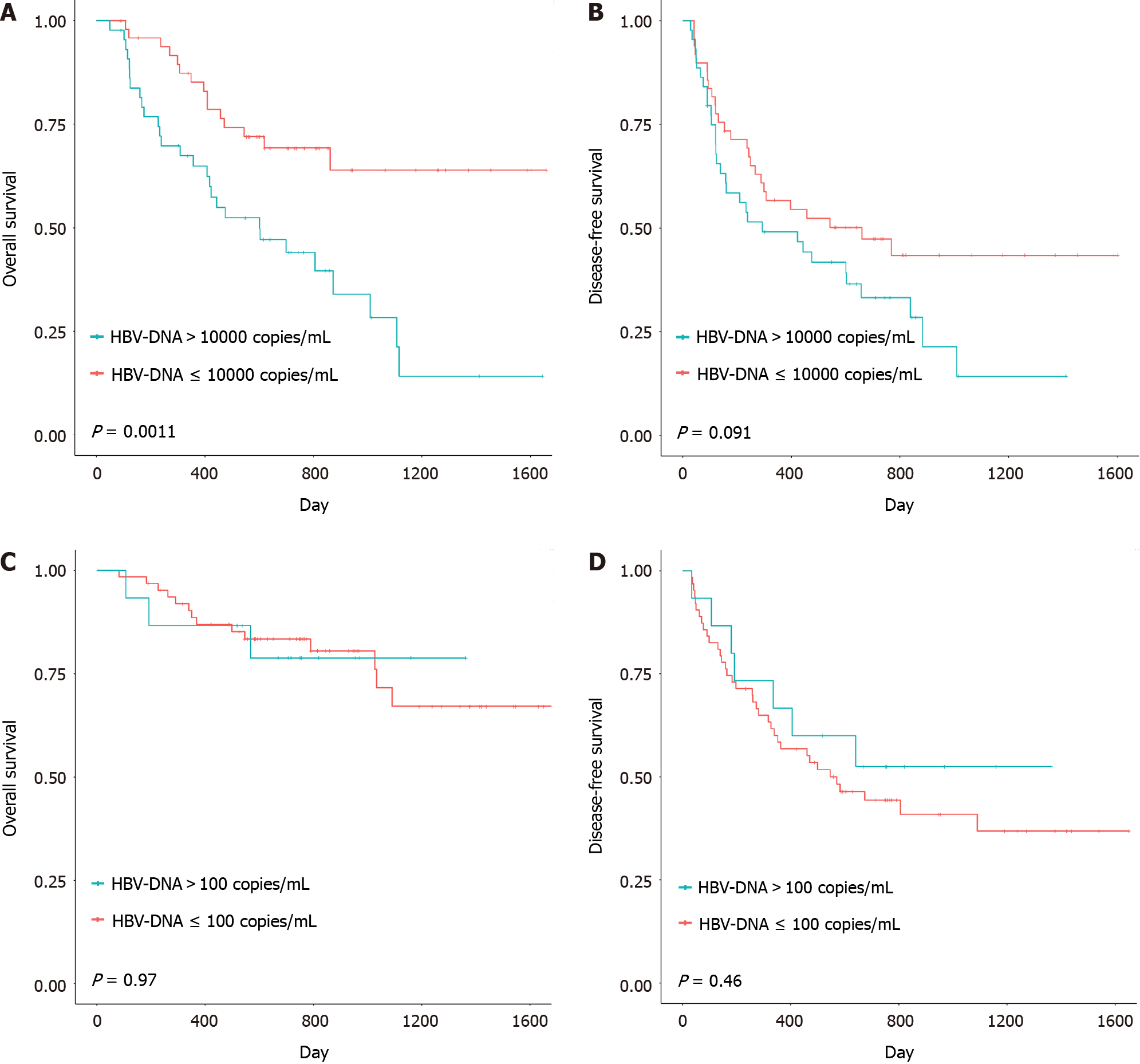

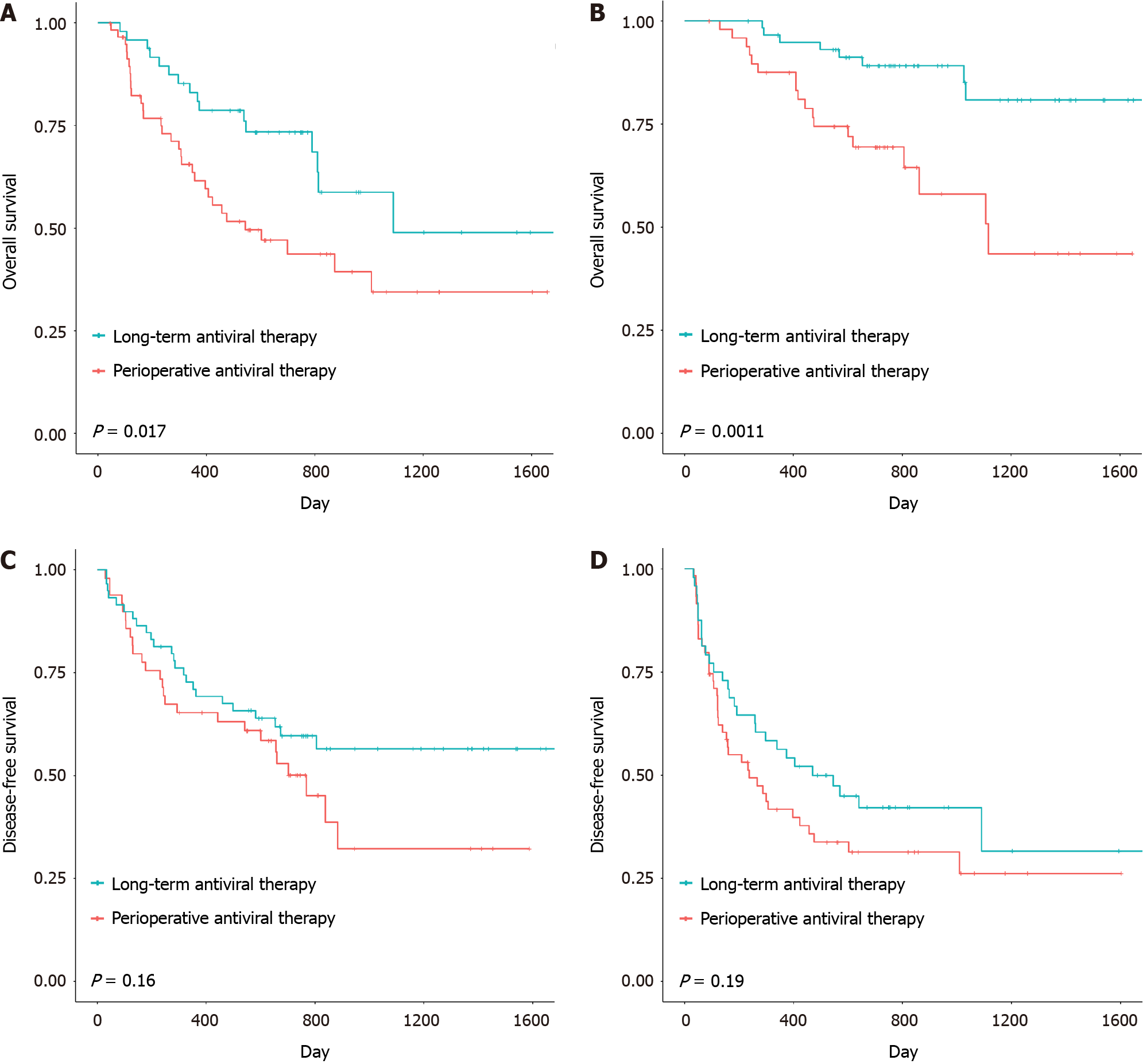

In the present study, we applied a reasonable surgical classification and explored the preoperative long-term prognosis of patients who received different surgical methods as defined for the two groups. The results showed that the OS of patients in the larger-range radical resection subgroup, which received preoperative long-term antiviral therapy, was significantly better than that of patients who received remedial perioperative antiviral therapy (P = 0.017) (Figure 4A). Moreover, the OS of patients in the wedge radical resection subgroup who received preoperative long-term antiviral therapy was significantly greater than that of patients who received remedial perioperative antiviral therapy (P = 0.0011) (Figure 4B). Moreover, there were no differences in DFS between the two groups, whether for large-range radical resection or for wedge radical resection (Figure 4C and D).

Despite recent advancements in surgical methods and equipment[11], liver resection for HCC, which is the most important treatment for HCC patients, still cannot effectively guarantee preoperative long-term survival[12]. Among patients who undergo radical surgery, the recurrence rate at 5 years is as high as 70%[13]. Antiviral therapy, including interferon and nucleotide analogs, can reduce the risk of cirrhosis and the incidence of HCC[14]. In addition, Sakamoto et al[15] reported that lack of antiviral therapy was an independent adverse prognostic factor (HR = 0.0229)[15]. However, the effect of antiviral therapy on survival and tumor recurrence after radical resection of HBV-related HCC remains controversial[16]. Moreover, some patients were found to have HCC and HBV infection at the same time; thus, antiviral therapy, which is considered a remedial treatment, was started since the perioperative period. This study was the first to evaluate the effects of preoperative long-term and remedial perioperative antiviral therapy on the prognosis after radical resection in HBV-related HCC patients. In the present study, compared with remedial perioperative antiviral therapy, preoperative long-term antiviral therapy for at least 24 wk before radical resection markedly improved survival after radical resection in HBV-related HCC patients. This phenomenon may be explained by the findings of existing studies, in which patients who received antiviral therapy and had reduced HBV-DNA levels achieved a better prognosis than those with consistently high HBV-DNA levels[17], and when patients received radical resection, those who had inferior preoperative viral loads had better outcomes[18]. Therefore, preoperative long-term antiviral therapy for at least 24 wk before radical resection may provide patients with better postoperative outcomes by decreasing preoperative HBV-DNA levels.

Previous studies have focused mainly on the difference in outcomes between patients who received perioperative antiviral therapy and patients who did not. Zhang reported that perioperative antiviral treatment improved patient safety by decreasing morbidity and accelerating recovery of postoperative liver function for HBV-related HCC resection[19]. However, the target HBV-DNA level for remedial perioperative antiviral therapy remains unknown. Hence, we stratified patient outcomes according to different HBV-DNA levels[20]. In our study, patients who had viral loads lower than 4 Log10 copies/mL in the remedial antiviral therapy group had significantly better overall survival than did those who did not (Figure 3A). Thus, remedial perioperative antiviral therapy could have potential benefits when the preoperative HBV-DNA concentration is less than 4 Log10 copies/mL.

However, in the preoperative long-term antiviral treatment group, no significant difference in survival was observed between the preoperative HBV-DNA negative subgroup and the preoperative HBV-DNA positive subgroup (Figure 3). Therefore, preoperative long-term antiviral treatment could provide a relatively better outcome regardless of whether the patient’s preoperative HBV-DNA status was positive or negative. Furthermore, the HBV-DNA load is closely related to postoperative liver function and tumor recurrence[21]. Hung reported that a preoperative viral load > 2000 IU/mL (4 Log10 copies/mL) was considered to be a risk factor for HCC recurrence after radical resection[22,23]. However, our results show that a preoperative HBV-DNA level of 4 Log10 copies/mL is not a good predictor of postoperative outcome.

In addition to reducing HBV-DNA levels, antiviral therapy can also affect patient prognosis in other ways. HBV can be reactivated by HCC treatment, thus increasing the risk of tumor recurrence[24]. In comparison with other treatments, such as radiofrequency ablation, radical resection is more likely to cause such adverse events[25]. Regardless of the radical resection approach, patients who receive preoperative long-term antiviral therapy have better outcomes than patients who receive remedial perioperative antiviral therapy (Figure 4). Preoperative long-term antiviral therapy is necessary for patients regardless of the type of radical resection procedure performed. The following reasons might explain these results. First, antiviral therapy can improve residual liver function and reduce postoperative complications, especially the incidence of liver insufficiency. The results showed that, compared with those in the remedial perioperative antiviral therapy group, patients in the preoperative long-term antiviral therapy group had better preoperative liver function. Two independent research groups also confirmed that intervention with antiviral drugs is beneficial for reducing the incidence of HBV reactivation and subsequent adverse events[26], and liver function is protected even though adverse events occur[27]. Second, this phenomenon may be related to the presence of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) in the residual liver. After hepatectomy, the residual liver is the most common site of tumor recurrence[28]. Specific to HBV-related HCC, HBV replication in noncancerous parts of the liver after hepatectomy may be related to the occurrence of new tumors[29], and cccDNA can persist in the infected liver even in the absence of detectable HBV-DNA, thereby affecting the replication of the virus in the remnant liver[30]. Although antiviral therapy is mainly intended to eliminate or silence cccDNA[31], eliminating cccDNA is difficult[32]. Fortunately, Bowden’s study showed that long-term therapy could play a role in eliminating cccDNA[33], suggesting that preoperative long-term antiviral therapy for at least 24 wk before radical resection may enable patients with chronic liver disease and marginal liver function to tolerate more extensive hepatectomy by controlling cccDNA expression and activity in the residual liver; hence, complete hepatectomy is a feasible method for improving the long-term survival rate of HCC patients.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center retrospective study, and more frequently generated or planned clinical data were not obtained for some patients. Moreover, some data were missing. Second, HBV-DNA levels were analyzed at only one time point rather than in terms of the pattern of changes in viral levels over an event range, and HBV levels at a single time point may not accurately reflect the inflammatory activity in each patient[34].

In conclusion, our study showed that preoperative long-term antiviral therapy is ideal for helping patients achieve better outcomes after radical resection of HBV-related HCC. The remedial perioperative antiviral therapy also can be helpful, especially when preoperative HBV-DNA levels are reduced to less than 4 Log10 copies/mL.

Antiviral therapy is an indispensable treatment for hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), especially for patients who need radical hepatectomy. Previous studies have focused mainly on the necessity of antiviral therapy, but there is no unified standard for perioperative antiviral therapy.

Several patients had HCC and HBV infection detected at the same time, so they received remedial treatment beginning in the perioperative period. The clinical efficacy of perioperative remedial antiviral treatment remains unclear.

This study was designed to investigate the outcome and potential influencing factors of perioperative remedial antiviral therapy in patients with operable HBV-related HCC. These results provide valuable information for the clinical treatment of HCC.

A total of 108 pairs of patients with HBV-related HCC were divided into two groups. The control group was given long-term preoperative antiviral therapy. The observation group was treated with remedial antiviral therapy. The outcome of treatment in the two groups, HBV DNA level, and surgical classification, were evaluated.

The overall survival and disease-free survival of patients in the preoperative long-term antiviral group were better than those in the perioperative remedial antiviral group, regardless of the removal range. History of preoperative antiviral treatment was independently associated with longer survival.

HBV-related HCC patients receiving preoperative long-term antiviral therapy achieve a better outcome after hepatectomy. For patients diagnosed with HCC whose HBV infection is first detected in the perioperative period, once the preoperative HBV DNA concentration decreases to less than 4 Log10 copies/mL, perioperative remedial antiviral treatment can also result in improved outcomes.

The long-term efficacy of perioperative remedial antiviral therapy, such as in the HBV DNA status and hepatitis B surface antigens, should be further studied.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Giacomelli L, Italy S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Brown ZJ, Tsilimigras DI, Ruff SM, Mohseni A, Kamel IR, Cloyd JM, Pawlik TM. Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:410-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Xie DY, Ren ZG, Zhou J, Fan J, Gao Q. 2019 Chinese clinical guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: updates and insights. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2020;9:452-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 66.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rizzo GEM, Cabibbo G, Craxì A. Hepatitis B Virus-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Viruses. 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Guan RY, Sun BY, Wang ZT, Zhou C, Yang ZF, Gan W, Huang JL, Liu G, Zhou J, Fan J, Yi Y, Qiu SJ. Antiviral therapy improves postoperative survival of patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2022;224:494-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim MN, Kim BK, Roh YH, Choi NR, Yu SJ, Kim SU. Comparable Efficacy Between Ongoing Versus Initiation of Antiviral Therapy at Treatment for HBV-related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1877-1880.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wong JS, Wong GL, Tsoi KK, Wong VW, Cheung SY, Chong CN, Wong J, Lee KF, Lai PB, Chan HL. Meta-analysis: the efficacy of anti-viral therapy in prevention of recurrence after curative treatment of chronic hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1104-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Huang G, Lau WY, Wang ZG, Pan ZY, Yuan SX, Shen F, Zhou WP, Wu MC. Antiviral therapy improves postoperative survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2015;261:56-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kawaguchi Y, Fuks D, Kokudo N, Gayet B. Difficulty of Laparoscopic Liver Resection: Proposal for a New Classification. Ann Surg. 2018;267:13-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kawaguchi Y, Hasegawa K, Tzeng CD, Mizuno T, Arita J, Sakamoto Y, Chun YS, Aloia TA, Kokudo N, Vauthey JN. Performance of a modified three-level classification in stratifying open liver resection procedures in terms of complexity and postoperative morbidity. Br J Surg. 2020;107:258-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu CJ, Huang WL, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Kao JH, Chen DS. End-of-treatment virologic response does not predict relapse after lamivudine treatment for chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3574-3578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Di Benedetto F, Magistri P, Di Sandro S, Sposito C, Oberkofler C, Brandon E, Samstein B, Guidetti C, Papageorgiou A, Frassoni S, Bagnardi V, Clavien PA, Citterio D, Kato T, Petrowsky H, Halazun KJ, Mazzaferro V; Robotic HPB Study Group. Safety and Efficacy of Robotic vs Open Liver Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:46-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lau WY, Lai EC. Hepatocellular carcinoma: current management and recent advances. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:237-257. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, Heimbach JK. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2121] [Cited by in RCA: 3237] [Article Influence: 462.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Hosaka T, Suzuki F, Kobayashi M, Seko Y, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, Akuta N, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Arase Y, Ikeda K, Kumada H. Long-term entecavir treatment reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2013;58:98-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 542] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sakamoto K, Beppu T, Hayashi H, Nakagawa S, Okabe H, Nitta H, Imai K, Hashimoto D, Chikamoto A, Isiko T, Kikuchi K, Baba H. Antiviral therapy and long-term outcome for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after curative liver resection in a Japanese cohort. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:1647-1655. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Zhou Y, Zhang Z, Zhao Y, Wu L, Li B. Antiviral therapy decreases recurrence of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection: a meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2014;38:2395-2402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim BK, Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JK, Kim KS, Choi JS, Moon BS, Han KH, Chon CY, Moon YM, Ahn SH. Persistent hepatitis B viral replication affects recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Liver Int. 2008;28:393-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yang T, Lu JH, Zhai J, Lin C, Yang GS, Zhao RH, Shen F, Wu MC. High viral load is associated with poor overall and recurrence-free survival of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:683-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang B, Xu D, Wang R, Zhu P, Mei B, Wei G, Xiao H, Zhang B, Chen X. Perioperative antiviral therapy improves safety in patients with hepatitis B related HCC following hepatectomy. Int J Surg. 2015;15:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | An HJ, Jang JW, Bae SH, Choi JY, Cho SH, Yoon SK, Han JY, Lee KH, Kim DG, Jung ES. Sustained low hepatitis B viral load predicts good outcome after curative resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1876-1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhou JY, Zhang L, Li L, Gu GY, Zhou YH, Chen JH. High hepatitis B virus load is associated with hepatocellular carcinomas development in Chinese chronic hepatitis B patients: a case control study. Virol J. 2012;9:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hung IF, Poon RT, Lai CL, Fung J, Fan ST, Yuen MF. Recurrence of hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with high viral load at the time of resection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1663-1673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huang G, Li PP, Lau WY, Pan ZY, Zhao LH, Wang ZG, Wang MC, Zhou WP. Antiviral Therapy Reduces Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence in Patients With Low HBV-DNA Levels: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2018;268:943-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huang G, Lai EC, Lau WY, Zhou WP, Shen F, Pan ZY, Fu SY, Wu MC. Posthepatectomy HBV reactivation in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma influences postoperative survival in patients with preoperative low HBV-DNA levels. Ann Surg. 2013;257:490-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Papatheodoridi M, Tampaki M, Lok AS, Papatheodoridis GV. Risk of HBV reactivation during therapies for HCC: A systematic review. Hepatology. 2022;75:1257-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lao XM, Luo G, Ye LT, Luo C, Shi M, Wang D, Guo R, Chen M, Li S, Lin X, Yuan Y. Effects of antiviral therapy on hepatitis B virus reactivation and liver function after resection or chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2013;33:595-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chong CC, Wong GL, Wong VW, Ip PC, Cheung YS, Wong J, Lee KF, Lai PB, Chan HL. Antiviral therapy improves post-hepatectomy survival in patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective-retrospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:199-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hung HH, Lei HJ, Chau GY, Su CW, Hsia CY, Kao WY, Lui WY, Wu WC, Lin HC, Wu JC. Milan criteria, multi-nodularity, and microvascular invasion predict the recurrence patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:702-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kuzuya T, Katano Y, Kumada T, Toyoda H, Nakano I, Hirooka Y, Itoh A, Ishigami M, Hayashi K, Honda T, Goto H. Efficacy of antiviral therapy with lamivudine after initial treatment for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1929-1935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Martinez MG, Boyd A, Combe E, Testoni B, Zoulim F. Covalently closed circular DNA: The ultimate therapeutic target for curing HBV infections. J Hepatol. 2021;75:706-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wong GLH, Gane E, Lok ASF. How to achieve functional cure of HBV: Stopping NUCs, adding interferon or new drug development? J Hepatol. 2022;76:1249-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Werle-Lapostolle B, Bowden S, Locarnini S, Wursthorn K, Petersen J, Lau G, Trepo C, Marcellin P, Goodman Z, Delaney WE 4th, Xiong S, Brosgart CL, Chen SS, Gibbs CS, Zoulim F. Persistence of cccDNA during the natural history of chronic hepatitis B and decline during adefovir dipivoxil therapy. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1750-1758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 691] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bowden S, Locarnini S, Chang TT, Chao YC, Han KH, Gish RG, de Man RA, Yu M, Llamoso C, Tang H. Covalently closed-circular hepatitis B virus DNA reduction with entecavir or lamivudine. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4644-4651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Yang HC, Su TH, Wang CC, Chen CL, Kuo SF, Liu CH, Chen PJ, Chen DS, Kao JH. High levels of hepatitis B surface antigen increase risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with low HBV load. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1140-1149.e3; quiz e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 445] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |