Published online Apr 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i4.1453

Peer-review started: December 5, 2023

First decision: December 18, 2023

Revised: December 31, 2023

Accepted: February 2, 2024

Article in press: February 2, 2024

Published online: April 15, 2024

Processing time: 127 Days and 19.5 Hours

Radiotherapy stands as a promising therapeutic modality for colorectal cancer (CRC); yet, the formidable challenge posed by radio-resistance significantly undermines its efficacy in achieving CRC remission.

To elucidate the role played by microRNA-298 (miR-298) in CRC radio-resistance.

To establish a radio-resistant CRC cell line, HT-29 cells underwent exposure to 5 gray ionizing radiation that was followed by a 7-d recovery period. The quantification of miR-298 levels within CRC cells was conducted through quantitative RT-PCR, and protein expression determination was realized through Western blotting. Cell viability was assessed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay and proliferation by clonogenic assay. Radio-induced apoptosis was discerned through flow cytometry analysis.

We observed a marked upregulation of miR-298 in radio-resistant CRC cells. MiR-298 emerged as a key determinant of cell survival following radiation exposure, as its overexpression led to a notable reduction in radiation-induced apoptosis. Intriguingly, miR-298 expression exhibited a strong correlation with CRC cell viability. Further investigation unveiled human dual-specificity tyrosine(Y)-regulated kinase 1A (DYRK1A) as miR-298’s direct target.

Taken together, our findings underline the role played by miR-298 in bolstering radio-resistance in CRC cells by means of DYRK1A downregulation, thereby positioning miR-298 as a promising candidate for mitigating radio-resistance in CRC.

Core Tip: Our findings indicate that microRNA-298 (miR-298) is upregulated in radio-resistant colorectal cancer (CRC) cells. Overexpression of miR-298 leads to decreased human dual-specificity tyrosine(Y)-regulated kinase 1A expression, ultimately enhancing the radio-resistance of CRC cells.

- Citation: Shen MZ, Zhang Y, Wu F, Shen MZ, Liang JL, Zhang XL, Liu XJ, Li XS, Wang RS. MicroRNA-298 determines the radio-resistance of colorectal cancer cells by directly targeting human dual-specificity tyrosine(Y)-regulated kinase 1A. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(4): 1453-1464

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i4/1453.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i4.1453

Malignant lesions arising in the colorectal mucosal epithelium give rise to colorectal cancer (CRC), a pervasive and life-threatening malady worldwide. Notably, neoadjuvant irradiation confers substantial advantages to individuals afflicted with CRC in comparison to surgical intervention alone. Research has demonstrated that following a course of five brief radiotherapy sessions delivering 5 gray (Gy) each, overall survival rates ascended from 30% to 38%, accompanied by a notable drop in local recurrence rates from 26% to 9%[1,2]. While radiotherapy stands as a highly efficacious therapeutic approach, the inherent radio-resistance exhibited by tumor cells frequently emerges as a formidable impediment to its effectiveness[3].

DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) represent the gravest form of damage inflicted upon chromatin by ionizing radiation (IR). The extent of DNA damage induced by IR varies depending on factors such as radiation dosage, cellular sensitivity to radiation, and DNA repair capabilities[4,5]. The generation of DSBs within specific genomic regions triggers histone H2AX phosphorylation near the injury site, giving rise to the formation of what are commonly known as γH2AX foci[6]. Within these lesions, a complex network interconnecting various biochemical pathways has evolved in cells to neutralize permanent DSB damage, facilitating lesion removal and the restoration of DNA integrity. The principal pathways encompass canonical non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ)[7], alternative NHEJ[8], and homologous recom

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) constitute a highly conserved family of small, non-coding RNAs that post-transcriptionally control gene expression by facilitating the degradation or impeding the translation of their target mRNAs. A mounting body of evidence underscores the involvement of miRNAs in a wide spectrum of both physiological and pathological processes[14]. Accumulating evidence has linked miR-298 dysregulation to CRC development, with miR-298 overexpression demonstrated to accelerate CRC cell proliferation and metastasis through the targeting of phosphatase and tensin homolog[15]. Yet, it remains to clarify the precise role played by miR-298 in the radio-resistance of CRC cells. Herein, we generated a radio-resistant cell strain and utilized it to scrutinize the genetic alterations induced by radiation that are associated with radio-resistance. Furthermore, we investigated the involvement of miR-298 in radio-resistance and revealed that it modulates radio-resistance in CRC cells by targeting DYRK1A.

We purchased CRC HT-29 cells from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained them in a fetal bovine serum (10%; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and penicillin-streptomycin (1%)-supplemented Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a humidified atmosphere with the temperature maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in air. They were then seeded in 60 mm culture dishes and exposed to a single dose of 5 Gy radiation using a 60 CO source.

To establish a radiation-resistant CRC cell line, the parental cells underwent a series of treatments. HT-29 cells were planted in 60 mm culture dishes (4 × 103 cells/dish) for IR at a dose of 5 Gy, followed by a 7-d recovery period. This process was repeated 24 times, resulting in a cumulative radiation dose of 120 Gy.

After cellular proteins isolation using a Protease Inhibitor Cocktail and Protein Phosphatase Inhibitor (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)-supplemented Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) buffer (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific), the protein samples were loaded onto a sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel and subsequently blotted onto a PVDF membrane. Primary antibodies (Abs) were applied and incubated overnight in 5% bovine serum albumin at 4 °C. Western blotting analysis was conducted using ImageJ software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The primary Abs used were β-actin Ab (1:2000, 3700S, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), ATM Ab (1:2000, ab201022, Abcam), p-ATM Ab (1:1000, ab81292, Abcam), cleaved caspase-3 Ab (1:1500, ab32042, Abcam), cleaved caspase-9 Ab (1:1500, ab2324, Abcam), 53BP1 Ab (1:1000, ab175933, Abcam), H2AX Ab (1:1000, 7631S, Cell Signaling Technology), and p-H2AX Ab (1:500, 9718S, Cell Signaling Technology). For secondary Abs, the following were used: HRP-linked anti-mouse IgG (1:8000, 7076P2) and HRP-linked anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000, 7074P2), both from Cell Signaling Technology.

Total RNA was meticulously extracted and purified from HT-29 cells following the precise guidelines provided by TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by skillful reverse-transcription of it into cDNA at a temperature of 37 °C for 15 min, employing the PrimeScript RT Master Mix cDNA synthesis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). A highly accurate qPCR analysis was then conducted utilizing SYBR Green (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

The primers employed were as follows: miR-298-forward: 5’-GAAGCAGGGAGGTTCTC-3’; miR-298-reverse: 5’-GAACATGTCTGCGTATCTC-3’.

All transfection experiments were meticulously conducted using the highly effective Effectene Transfection Reagent (Qiagen GmbH), strictly following its meticulously detailed recommendations. The essential reagents, including DYRK1A siRNA (si-DYRK1A), miR-298 mimic, miR-298 inhibitor, and the negative control (NC), were all procured from the esteemed supplier Gene Pharma (Shanghai, China). Moreover, for the purpose of this study, the cDNA corresponding to human DYRK1A was skillfully amplified through PCR and subsequently integrated into the pcDNA3.0 empty vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to meticulously engineer the pcDNA-DYRK1A vector.

For the generation of miR-298-overexpressing HT-29 cell lines, we employed human pre-miRNA expression constructs, namely lenti-miR-298 (MI0005523), which were thoughtfully procured from System Biosciences. In addition, we used an anti-miR scramble control lentiviral vector (scramble) for control purposes. The methodology involved infecting HT-29 cells with lentiviral particles carrying the miR-298 encoding sequence. To establish stable cell lines expressing miR-298, a prudent selection process using puromycin was meticulously conducted.

We purchased 6-8 wk-old BALB/c nude mice, all males, from the Animal Experiment Center of Guangxi Medical University. These mice were meticulously maintained in a controlled laboratory environment, featuring a temperature of 23 °C ± 2 °C, humidity at 50% ± 5%, and a light/dark (10/14 h) cycle. It’s worth noting that approval has been received from the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University, and all the facilities adhered to ethical standards. To induce CRC tumors, we prepared miR-298-overexpressing HT-29 cells as well as cells transfected with scrambled control. After suspension in DMEM (200 µL), these cells were injected subcutaneously into the mouse right hind feet. Once the xenografts reached a mean size of 20 mm3, the tumor-bearing mice were randomly grouped as follows, each consisting of 5 mice: Scramble-UT: Mice in this group did not receive any treatment; rLV-miR-298-UT: Again, this group of mice did not undergo any treatment; rLV-miR-298-IR: Mice were treated with 5 Gy IR exposure on the 0, 4th d, and 8th d; rLV-miR-298-IR: Similar to the previous group, these animals were subjected to 5 Gy IR exposure on the 0, 4th d, and 8th d. Tumor size was regularly assessed by measuring dimensions with calipers on days 0, 4, 8, and 12. The tumor volume for each mouse was calculated using the formula: V (mm3) =1/6 π × length (mm) × width2 (mm2). At the conclusion of the experiment, which took place 20 days after tumor implantation, the mice were euthanized to carefully excise the tumor, which was then weighed and photographed for analysis.

HT-29 cells were initially seeded into the wells (4000-8000 cells/well) of 6-well plates. Subsequently, these cells were subjected to IR treatment. After a period of 12 d, colonies that had formed were meticulously fixed using 10% formalin at room temperature for a duration of 10 min. Following this, the colonies were stained with a 0.02% crystal violet solution for another 10 min, also at room temperature. The number of cells within each colony was then quantified under a dissection microscope. The survival fraction was subsequently determined by expressing it as the ratio of the relative plating efficiencies of irradiated cells to non-irradiated cells.

We employed a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) to determine cell viability, with the procedures conducted as per the instructions. Briefly, cells were planted into the wells of 96-well plates and allowed to grow until reaching approximately 75% confluence. After the designated treatment, MTT solution with a concentration of 5 mg/mL was introduced into each well for a 4-h cultivation at 37 °C. DMSO (50 μL) was added to each well after solution removal, followed by absorbance (490 nm) measurement utilizing a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Quantitative data, derived from a minimum of three independent experiments, are presented in the form the mean ± SD. Data obtained from these experiments were subjected to statistical analysis using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests, with SPSS 22.0 software (IBM Corp.). The presence of statistical significance is indicated by P < 0.05.

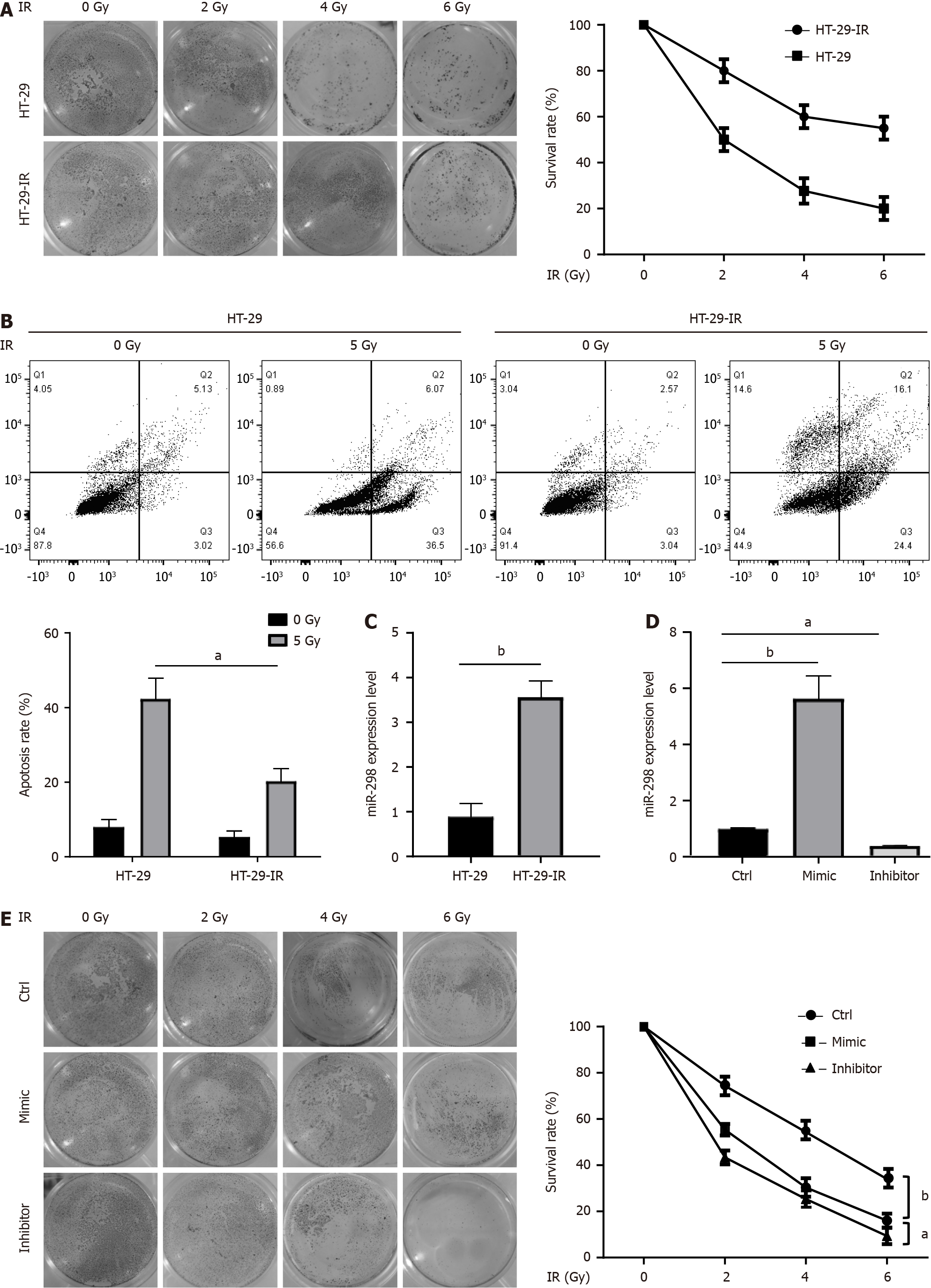

First, we generated a radio-resistant CRC cell line by exposing HT-29 cells to 120 Gy IR over a two-week treatment. In comparison to the parental cells, HT-29-IR cells exhibited an obvious increase in radio-resistance. To confirm these observed phenotypes, we assessed the survival rate through a clonogenic assay in irradiated HT-29-IR cells. The results demonstrated resistance of HT-29-IR to radiation-induced cell death in comparison to their parental counterparts (Figure 1A). Furthermore, flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis consistently indicated that HT-29-IR cells were highly resistant to radiation-induced apoptotic cell death (Figure 1B). It was found that miR-298 was upregulated in HT-29-IR, suggesting the potential involvement of miR-298 in radio-resistance of CRC (Figure 1C). To explore the role of miR-298, HT-29 cells overexpressing miR-298 and knocking down miR-298 were transfected with miR-298 mimic and miR-298 inhibitor, respectively. Overexpression or knockdown efficiency was confirmed by qPCR (Figure 1D). Notably, clono

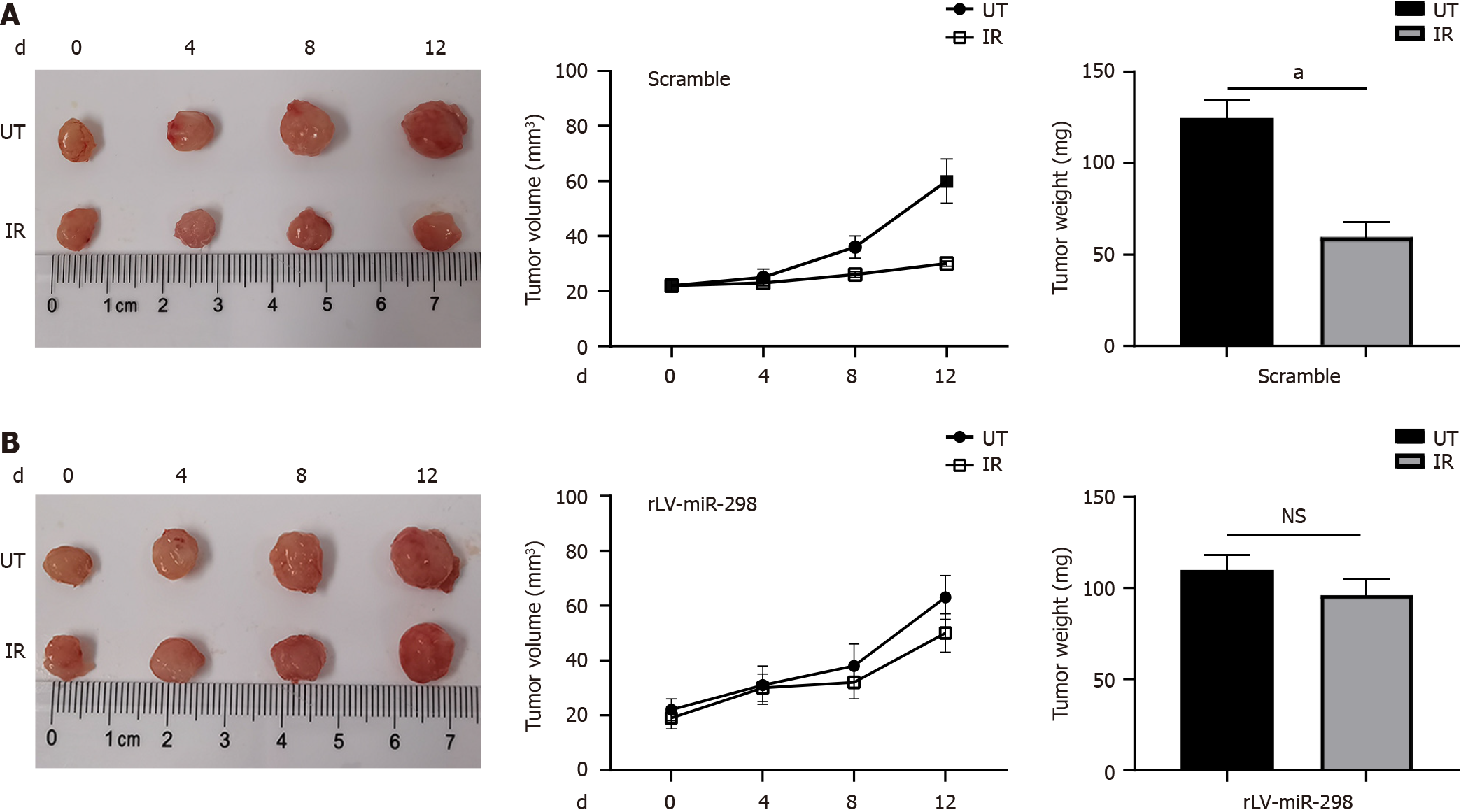

To verify the specificity of the function of miR-298 in radio-resistance, an ectopic (subcutaneous) CRC model in nude mice was generated as described previously[16]. The subcutaneous implantation of scamble-transfected cells resulted in growing tumors, which is suppressed by a single dose of local radiation (Figure 2A). However, the data of tumor size and weight showed that overexpression of miR-298 rendered xenograft more resistance to radiation treatment (Figure 2B). These findings suggested that miR-298 overexpression reduced radio-sensitivity in CRC tumors in vivo.

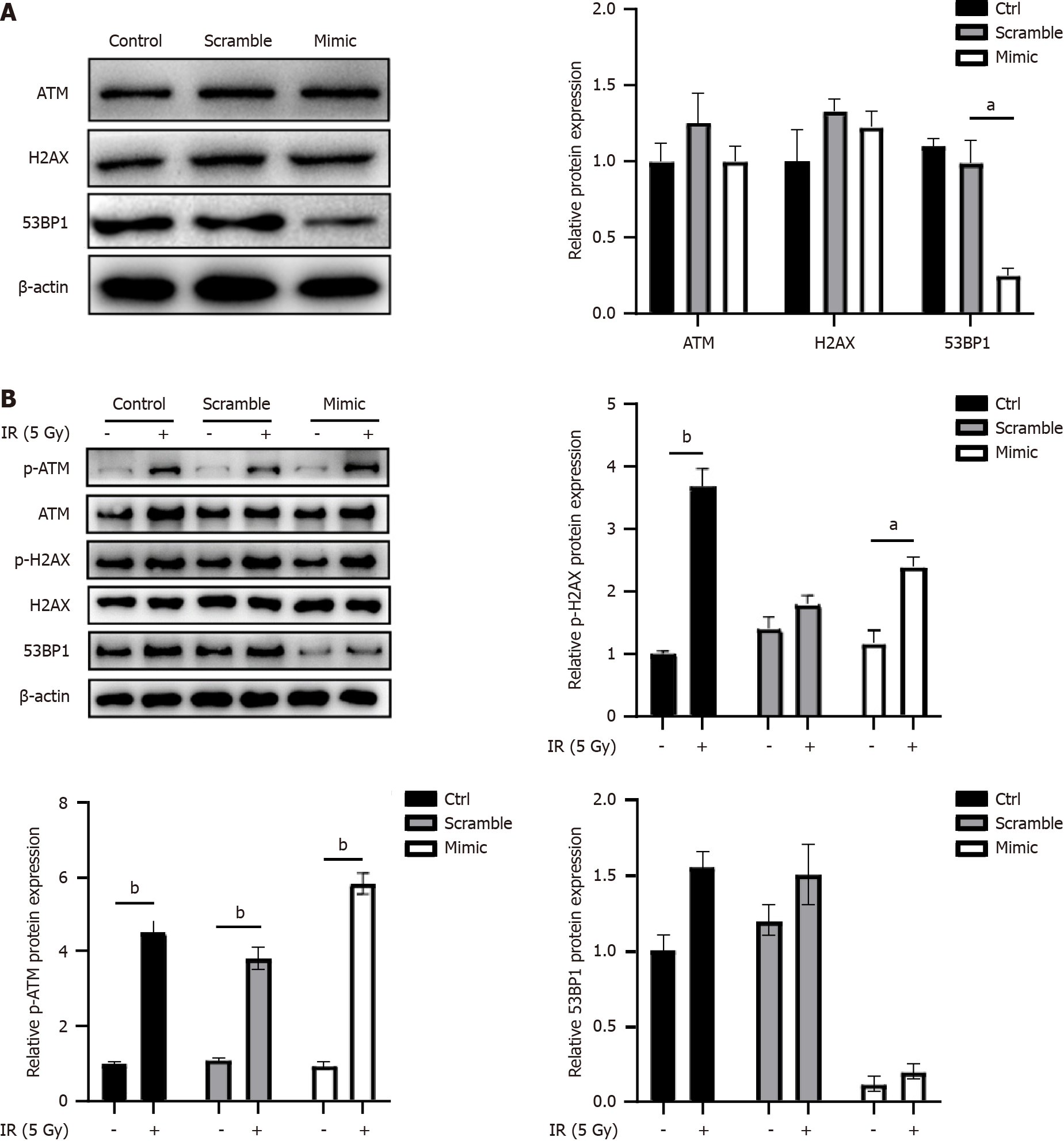

In response to radiation, DNA damage response proteins such as H2AX, ATM, and 53BP1 were recruited to the double-strand breaks sites. Subsequently, the role played by miR-298 in DNA damage was examined. As shown in Figure 3A, overexpression of miR-298 decreased 53BP1 protein levels, but did not alter the expression of H2AX and ATM. In addition, miR-298 overexpression displayed no notable effects on radiation-induced phosphorylated ATM and H2AX, but reduced 53BP1 expression (Figure 3B). This suggested that miR-298 is required for maintaining 53BP1 expression.

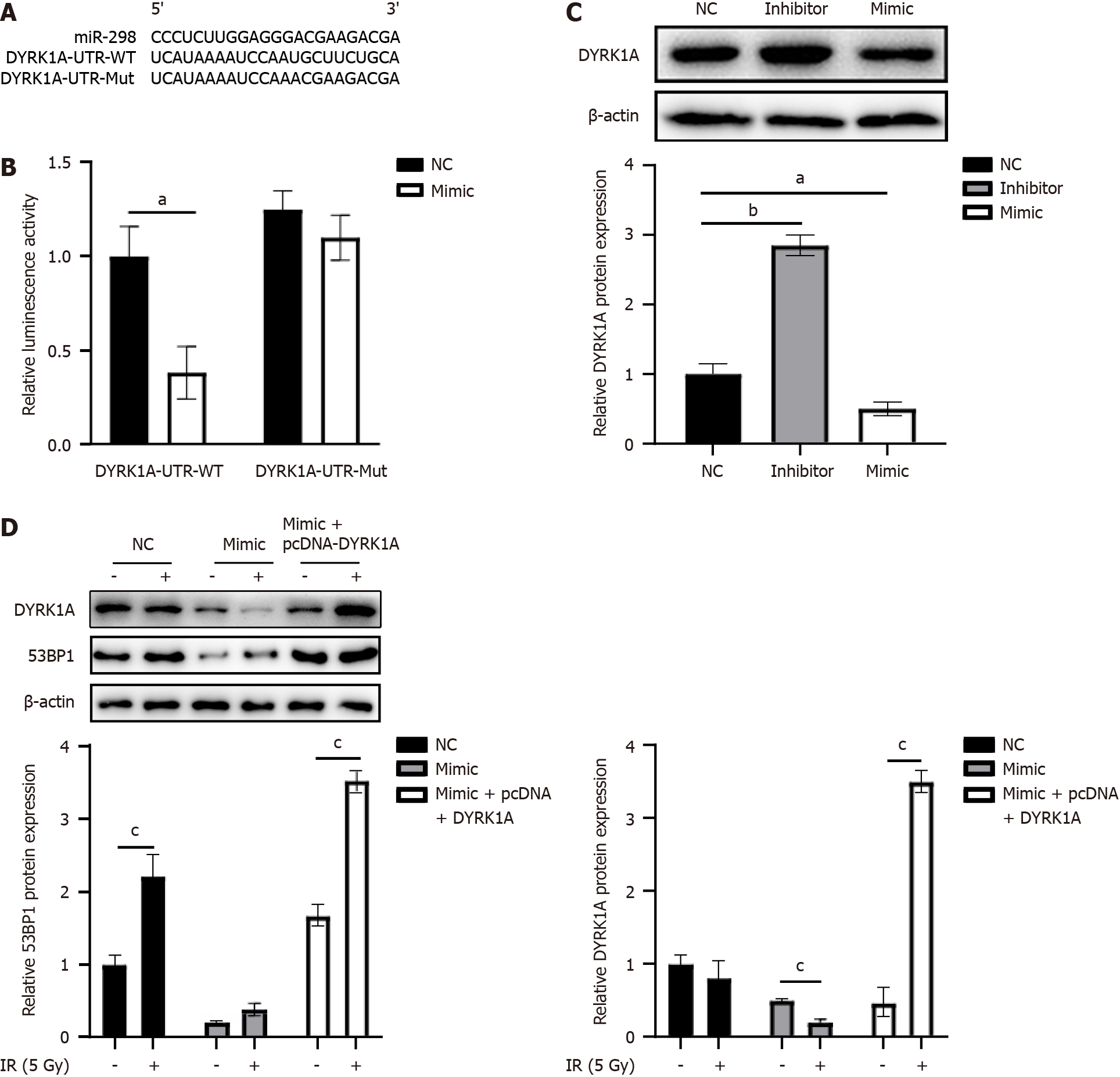

We utilized TargetScan (URL: http://www.targetscan.org) to predict miR-298’s potential target genes. The analysis results revealed that, while 53BP1 is not a direct target of miR-298, miR-298 could target DYRK1A (Figure 4A), a gene required for maintaining 53BP1 expression and its subsequent recruitment to DNA damage loci. Further, a luciferase reporter assay was carried out to assess the direct association of miR-298 with DYRK1A. HT-29 cells were co-transfected with DYRK1A-UTR-WT- or DYRK1A-UTR-Mut-containing luciferase reporters along with miR-298 mimics. The luciferase reporter assay results indicated a 51% inhibition of luciferase activity in cells transfected with miR-298 mimic fused to DYRK1A UTR, compared to the NC (Figure 4B). Additionally, DYRK1A expression was reduced in miR-298 mimic group but enhanced in miR-298 inhibitor group (Figure 4C). Compared with the NC group, the expressions of 53BP1 and DYRK1A proteins in the mimc group were significantly decreased under 5-cy treatment, while the expressions of 53BP1 and DYRK1A proteins in the mimc + pcDNA-DYRK1A group were significantly increased compared with the mimc group. Notably, pcDNA-DYRK1A vector-transfected HT-29 cells were able to rescue the decreased expression of 53BP1 induced by miR-298 overexpression (Figure 4D), suggesting that miR-298 regulates 53BP1 expression in a DYRK1A-dependent manner.

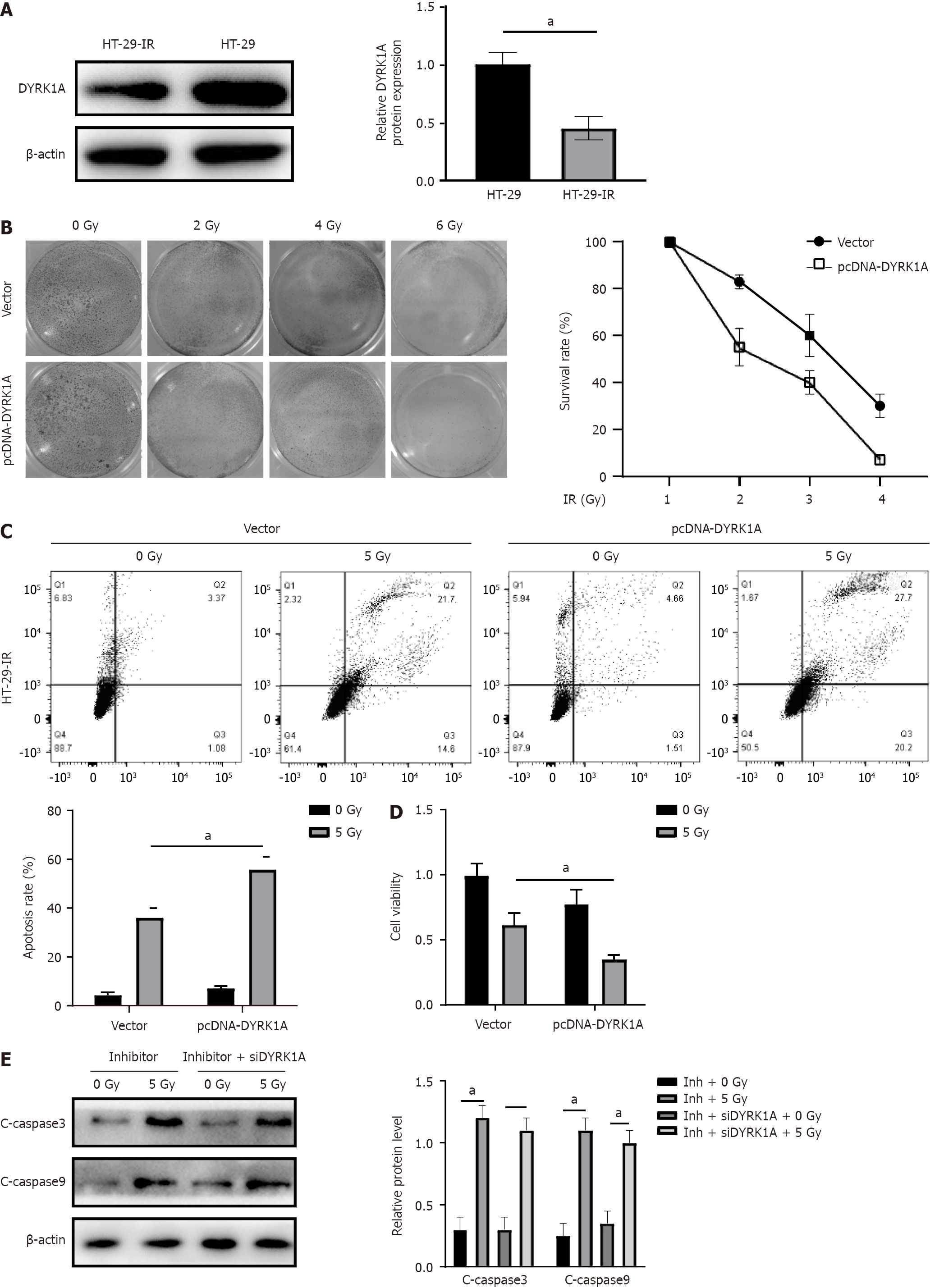

We assessed DYRK1A expression in both HT-29 and HT-29-IR cells via Western blotting analysis. Interestingly, DYRK1A was observed to be under-expressed in radio-resistant cells (Figure 5A). To investigate whether DYRK1A expression influences radiation resistance, we transfected HT-29 cells with a pcDNA-DYRK1A vector, with pcDNA empty vector-transfected cells served as controls. According to the clonogenic assay, cells characterized by DYRK1A overexpression exhibited a reduced survival rate (Figure 5B). Furthermore, flow cytometry apoptosis assay results indicated that DYRK1A-transfected HT-29-IR cells displayed increased sensitivity to radiation (Figure 5C). MTT assay identified weakened cell viability in the pcDNA-DYRK1A group versus the control group (Figure 5D), suggesting that DYRK1A may functionally enhance radio-sensitivity. Intriguingly, miR-298 downregulation in HT-29 realized through inhibitor transfection significantly enhanced radiation-induced cleaved-caspase3 and cleaved-caspase9, and this effect was counteracted by DYRK1A silencing (Figure 5E). These results imply that miR-298 reduces radiation-induced CRC cell apoptosis and radio-sensitivity by modulating DYRK1A expression.

Radiotherapy resistance is considered a conundrum to decipher in radiotherapy treatment of CRC. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the mechanism underlying radio-resistance is important to enhance radiotherapy efficacy. After radiation, some cellular processes begin to repair the damage, whereas cells that fail repair undergo death[17]. In this study, a radiation resistant HT-29 (HT-29-IR) cell strain was established, with which an in vitro model was built to study the molecular mechanisms behind radio-resistance. The results showed that caspases activity and apoptosis of HT-29-IR cells decreased after irradiation. Additionally, a connection between high miR-298 expression in tumors and CRC cell radio-resistance was determined.

Indeed, there is compelling evidence that miR-298 is essential in the regulation of various signaling transduction mediators, contributing to cell cycle regulation and tumour survival. For instance, miR-298 showed upregulated expression in prostate cancer tissues than in normal counterparts[18]. Moreover, overexpressing miR-298 reduces hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasiveness by suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin axis[19]. Furthermore, miR-298 inhibited pro-apoptotic Bcl-2-associated X (BAX) protein expression, leading to decreased gastric carcinoma cell apoptosis[20]. Upregulated miR-298 was found in radio-resistant CRC cells in the present study. Overexpressing miR-298 reduced radiation-induced apoptosis. In vitro experiment, it was also confirmed the beneficial role: MiR-298 overexpression decreased radio-sensitivity of CRC tumors. The present study showed miR-298 is required for the basal expression of 53BP1, a DNA repair protein that rapidly recruited to the DSB site following exposure to radiation[21]. 53BP1 Localization to DSBs depends on multiple chromatin changes that occur in the vicinity of DNA damage. Studies have shown that 53BP1 and di-methylation of histone H4 lysine 20 (H4K20me2) is closely related to DNA damage induced by radiation[22,23]. Besides, RNF8 and RNF168, the RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligases, are essential for 53BP1 recruitment[13,24].

According to predictions from the TargetScan database, miR-298 appears to directly target DYRK1A. Previous research has reported that the knockdown of DYRK1A reduced p53Ser-15 phosphorylation in neurons[25]. DYRK1A plays a part in regulating mitochondrial apoptotic signaling by increasing the levels of mitochondrial apoptotic proteins, including caspase-9/3. Additionally, a study by Laguna et al[26] demonstrated the ability of DYRK1A to modulate caspase-9-mediated apoptosis during retinal development. Consistent with prior reports[27], our study reveals that DYRK1A is downregulated in radio-resistant CRC cells. Lan et al[28] showed that DYRK1A is a target of radiotherapy sensitization in pancreatic cancer. Their study confirmed that DYRK1A inhibition, used in combination with radiotherapy, increases DNA double-strand breaks and impacts homologous repair, leading to more cancer cell death. Consequently, DYRK1A may function as a tumor suppressor due to its ability to promote radio-sensitivity in CRC cells. This study has shed light on the roles of miR-298 and DYRK1A in CRC cells. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of miR-298’s function, clinical analyses should be considered to assess its diagnostic and prognostic value in CRC.

In summary, our findings indicate that miR-298 is upregulated in radio-resistant CRC cells. Overexpression of miR-298 leads to decreased DYRK1A expression, ultimately enhancing the radio-resistance of CRC cells.

Radiotherapy stands as a promising therapeutic modality for colorectal cancer (CRC); yet, the formidable challenge posed by radio-resistance significantly undermines its efficacy in achieving CRC remission.

Radiotherapy can effectively inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells, but a considerable number of CRC patients are still resistant to radiotherapy, and further exploration of potential drug resistance targets is needed to provide a theoretical basis for developing effective treatment strategies to improve response rate.

To analyze the role of microRNA-298 (miR-298) in the radioresistance of CRC and its molecular mechanism. MiRNAs are involved in a wide range of physiological and pathological processes, and the dysregulation of miR-298 has been shown to be related to the development of CRC. However, the exact role that miR-298 plays in the radioresistance of CRC cells remains to be elucidated.

This study established a radiation-resistant CRC cell line, which exposes HT-29 cells to 5 gray ionizing radiation, followed by a 7-d recovery period. The miR-298 expression level and the biological behavior of HT-29 cells were examined before and after radiotherapy. To explore the radiosensitivity and the expression of downstream target genes in ectopic CRC model tumors after overexpressing miR-298. Dual-luciferase reporter assay for the binding site of DYRK1A with miR-298. Knockdown of miR-298 observed DYRK1A expression and radiation-induced apoptosis were improved in HT-29 cells.

We observed a significant upregulation of miR-298 in radioresistant CRC cells. MiR-298 emerged as a key determinant of cell survival after radiation exposure, as its overexpression resulted in a significant reduction in radiation-induced apoptosis. Interestingly, there was a strong correlation between miR-298 expression and CRC cell viability. Further studies revealed DYRK1A as a direct target of miR-298. Taken together, our results highlight the role that miR-298 plays in enhancing radioresistance in CRC cells by downregulation of DYRK1A, thereby positioning miR-298 as a promising candidate gene.

This study revealed an important target of CRC resistance to radiotherapy, miR-298, an effect of DYRK1A to enhance radioresistance in CRC cells. This study provides proof of principle for the development of a protocol based on radiotherapy + targeting for CRC.

Cancer radiotherapy resistance remains a major challenge for cancer patients. To improve patient outcomes, we need to further understand the mechanisms by which tumor ecosystem tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and migration under the induction of continuous therapy. Analysis of the targets of radiotherapy sensitive/resistant to tumors will help to discover new therapeutic opportunities.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ahn KS, South Korea; Buhrmann C, Germany S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Folkesson J, Birgisson H, Pahlman L, Cedermark B, Glimelius B, Gunnarsson U. Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial: long lasting benefits from radiotherapy on survival and local recurrence rate. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5644-5650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 564] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Häfner MF, Debus J. Radiotherapy for Colorectal Cancer: Current Standards and Future Perspectives. Visc Med. 2016;32:172-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wu QB, Sheng X, Zhang N, Yang MW, Wang F. Role of microRNAs in the resistance of colorectal cancer to chemoradiotherapy. Mol Clin Oncol. 2018;8:523-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Falk M, Hausmann M, Lukášová E, Biswas A, Hildenbrand G, Davídková M, Krasavin E, Kleibl Z, Falková I, Ježková L, Štefančíková L, Ševčík J, Hofer M, Bačíková A, Matula P, Boreyko A, Vachelová J, Michaelidesová A, Kozubek S. Determining Omics spatiotemporal dimensions using exciting new nanoscopy techniques to assess complex cell responses to DNA damage: part A--radiomics. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2014;24:205-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jezkova L, Zadneprianetc M, Kulikova E, Smirnova E, Bulanova T, Depes D, Falkova I, Boreyko A, Krasavin E, Davidkova M, Kozubek S, Valentova O, Falk M. Particles with similar LET values generate DNA breaks of different complexity and reparability: a high-resolution microscopy analysis of γH2AX/53BP1 foci. Nanoscale. 2018;10:1162-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858-5868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3946] [Cited by in RCA: 4140] [Article Influence: 153.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chang HHY, Pannunzio NR, Adachi N, Lieber MR. Non-homologous DNA end joining and alternative pathways to double-strand break repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:495-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 828] [Cited by in RCA: 1168] [Article Influence: 146.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iliakis G, Murmann T, Soni A. Alternative end-joining repair pathways are the ultimate backup for abrogated classical non-homologous end-joining and homologous recombination repair: Implications for the formation of chromosome translocations. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2015;793:166-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jasin M, Rothstein R. Repair of strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a012740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 657] [Cited by in RCA: 636] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Birchler JA, Riddle NC, Auger DL, Veitia RA. Dosage balance in gene regulation: biological implications. Trends Genet. 2005;21:219-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Korbel JO, Tirosh-Wagner T, Urban AE, Chen XN, Kasowski M, Dai L, Grubert F, Erdman C, Gao MC, Lange K, Sobel EM, Barlow GM, Aylsworth AS, Carpenter NJ, Clark RD, Cohen MY, Doran E, Falik-Zaccai T, Lewin SO, Lott IT, McGillivray BC, Moeschler JB, Pettenati MJ, Pueschel SM, Rao KW, Shaffer LG, Shohat M, Van Riper AJ, Warburton D, Weissman S, Gerstein MB, Snyder M, Korenberg JR. The genetic architecture of Down syndrome phenotypes revealed by high-resolution analysis of human segmental trisomies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12031-12036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tejedor FJ, Hämmerle B. MNB/DYRK1A as a multiple regulator of neuronal development. FEBS J. 2011;278:223-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Menon VR, Ananthapadmanabhan V, Swanson S, Saini S, Sesay F, Yakovlev V, Florens L, DeCaprio JA, Washburn MP, Dozmorov M, Litovchick L. DYRK1A regulates the recruitment of 53BP1 to the sites of DNA damage in part through interaction with RNF169. Cell Cycle. 2019;18:531-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Qin X, Wang X, Wang Y, Tang Z, Cui Q, Xi J, Li YS, Chien S, Wang N. MicroRNA-19a mediates the suppressive effect of laminar flow on cyclin D1 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3240-3244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arabsorkhi Z, Gharib E, Yaghmoorian Khojini J, Farhadieh ME, Nazemalhosseini-Mojarad E, Zali MR. miR-298 plays a pivotal role in colon cancer invasiveness by targeting PTEN. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:4335-4350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang Y, Zhao M, Zhao H, Cheng S, Bai R, Song M. MicroRNA-940 restricts the expression of metastasis-associated gene MACC1 and enhances the antitumor effect of Anlotinib on colorectal cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:2809-2822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hill MA. Radiation damage to DNA: the importance of track structure. Radiat Meas. 1999;31:15-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Krell J, Stebbing J, Carissimi C, Dabrowska AF, de Giorgio A, Frampton AE, Harding V, Fulci V, Macino G, Colombo T, Castellano L. TP53 regulates miRNA association with AGO2 to remodel the miRNA-mRNA interaction network. Genome Res. 2016;26:331-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cao N, Mu L, Yang W, Liu L, Liang L, Zhang H. MicroRNA-298 represses hepatocellular carcinoma progression by inhibiting CTNND1-mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:483-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhao H, Zhao D, Tan G, Liu Y, Zhuang L, Liu T. Bufalin promotes apoptosis of gastric cancer by down-regulation of miR-298 targeting bax. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:3420-3428. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Zimmermann M, de Lange T. 53BP1: pro choice in DNA repair. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:108-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Botuyan MV, Lee J, Ward IM, Kim JE, Thompson JR, Chen J, Mer G. Structural basis for the methylation state-specific recognition of histone H4-K20 by 53BP1 and Crb2 in DNA repair. Cell. 2006;127:1361-1373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 784] [Article Influence: 43.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pei H, Zhang L, Luo K, Qin Y, Chesi M, Fei F, Bergsagel PL, Wang L, You Z, Lou Z. MMSET regulates histone H4K20 methylation and 53BP1 accumulation at DNA damage sites. Nature. 2011;470:124-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Faustrup H, Melander F, Bartek J, Lukas C, Lukas J. RNF8 ubiquitylates histones at DNA double-strand breaks and promotes assembly of repair proteins. Cell. 2007;131:887-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 862] [Cited by in RCA: 909] [Article Influence: 50.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Park J, Oh Y, Yoo L, Jung MS, Song WJ, Lee SH, Seo H, Chung KC. Dyrk1A phosphorylates p53 and inhibits proliferation of embryonic neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:31895-31906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Laguna A, Aranda S, Barallobre MJ, Barhoum R, Fernández E, Fotaki V, Delabar JM, de la Luna S, de la Villa P, Arbonés ML. The protein kinase DYRK1A regulates caspase-9-mediated apoptosis during retina development. Dev Cell. 2008;15:841-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zou Y, Yao S, Chen X, Liu D, Wang J, Yuan X, Rao J, Xiong H, Yu S, Zhu F, Hu G, Wang Y. LncRNA OIP5-AS1 regulates radioresistance by targeting DYRK1A through miR-369-3p in colorectal cancer cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2018;97:369-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lan B, Zeng S, Zhang S, Ren X, Xing Y, Kutschick I, Pfeffer S, Frey B, Britzen-Laurent N, Grützmann R, Cordes N, Pilarsky C. CRISPR-Cas9 Screen Identifies DYRK1A as a Target for Radiotherapy Sensitization in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |