Published online Apr 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i4.1334

Peer-review started: December 18, 2023

First decision: January 4, 2024

Revised: January 15, 2024

Accepted: February 20, 2024

Article in press: February 20, 2024

Published online: April 15, 2024

Processing time: 114 Days and 23.5 Hours

This study aimed to evaluate the safety of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) in elderly patients with gastric cancer (GC).

To evaluate the safety of ERAS in elderly patients with GC.

The PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases were used to search for eligible studies from inception to April 1, 2023. The mean difference (MD), odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) were pooled for analysis. The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores. We used Stata (V.16.0) software for data analysis.

This study consists of six studies involving 878 elderly patients. By analyzing the clinical outcomes, we found that the ERAS group had shorter postoperative hospital stays (MD = -0.51, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = -0.72 to -0.30, P = 0.00); earlier times to first flatus (defecation; MD = -0.30, I² = 0.00%, 95%CI = -0.55 to -0.06, P = 0.02); less intestinal obstruction (OR = 3.24, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 1.07 to 9.78, P = 0.04); less nausea and vomiting (OR = 4.07, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 1.29 to 12.84, P = 0.02); and less gastric retention (OR = 5.69, I2 = 2.46%, 95%CI = 2.00 to 16.20, P = 0.00). Our results showed that the conventional group had a greater mortality rate than the ERAS group (OR = 0.24, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.07 to 0.84, P = 0.03). However, there was no statistically significant difference in major complications between the ERAS group and the conventional group (OR = 0.67, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.38 to 1.18, P = 0.16).

Compared to those with conventional recovery, elderly GC patients who received the ERAS protocol after surgery had a lower risk of mortality.

Core Tip: This study was the first pooling up analysis to evaluate the safety of enhanced recovery after surgery in elderly patients with gastric cancer. In conclusion, compared to those with conventional recovery, elderly gastric cancer (GC) patients who received the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol after surgery had a lower risk of mortality. The ERAS protocol was determined to be safe in elderly patients with GC.

- Citation: Li ZW, Luo XJ, Liu F, Liu XR, Shu XP, Tong Y, Lv Q, Liu XY, Zhang W, Peng D. Is recovery enhancement after gastric cancer surgery really a safe approach for elderly patients? World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(4): 1334-1343

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i4/1334.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i4.1334

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide[1,2]. It has been reported that more than 50% of GC occur in East Asian countries[3,4]. Among the various treatments available, surgery is the cornerstone of treatment for patients with GC[5-7]. Although the development of surgical techniques has advanced, postoperative complications and mortality are still high[8]. According to a previous study, the postoperative mortality rate is as high as 4%[9]. Therefore, how to reduce postoperative complications and mortality has become the focus of surgeons.

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) is primarily defined as a multimodal strategy that optimizes perioperative management to improve surgical outcomes and enhance postoperative recovery[10]. This strategy includes preoperative carbohydrate loading, early oral feeding, and early postoperative activity[11]. The ERAS protocol has been proven to reduce the rate of postoperative complications and shorten the postoperative hospital stay for patients with digestive tract cancer [12,13].

With the gradual aging of the population, the number of elderly patients with GC is also increasing[14-16]. Elderly patients usually have a poor physiological function, more comorbidities, and slower recovery after surgery. The use of the ERAS protocol in elderly patients with GC has been reported[17]. However, for elderly patients with GC, there is no convincing evidence that the ERAS protocol is a safe and effective measure. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the safety of ERAS in older patients with GC.

This study was conducted by the PRISMA statement[18].

The PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases were searched from inception to April 1, 2023. The following keywords related to ERAS were used for the search: “enhanced recovery after surgery” OR “ERAS” OR “enhanced recovery” OR “enhanced recovery protocols” OR “enhanced rehabilitation” OR “perioperative care” OR “conventional care” OR “early recovery” OR “fast track” OR “multimodal perioperative protocol” OR “standard care” OR “care standard”. As for GC, the search strategy was “gastric cancer” OR “gastric carcinoma” OR “gastric neoplasms” OR “stomach cancer” OR “stomach carcinoma” OR “stomach neoplasms”. As for older, the searching strategy was “aged” OR “older” OR “older adult” OR “older patients” OR “elderly”. Then, we combined these items with “AND”. The search was limited to title and abstract. The language available was English. And two authors performed the search independently.

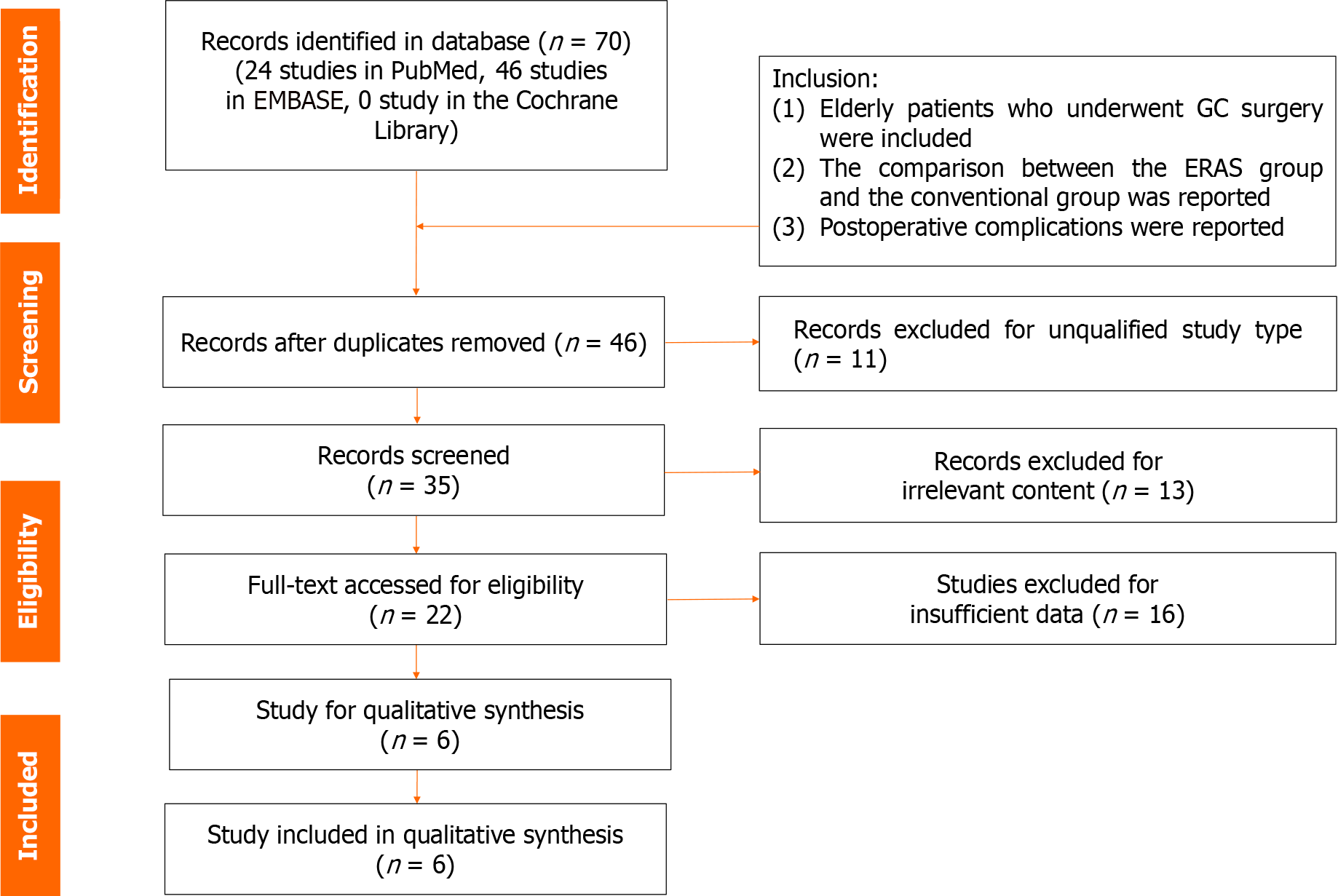

The studies were included in this study if they met the following criteria: (1) Elderly patients who underwent GC surgery; (2) the comparison between the ERAS group and the conventional group was reported; and (3) postoperative complications were reported. The exclusion criteria of this study were as follows: (1) Conferences, reviews, letters, comments, or case reports, duplicated publication data; and (2) insufficient data for analysis. All disagreements about inclusion and exclusion were solved by group discussion.

Two authors searched the database independently. First, after removing the duplicate records, and then the titles and abstracts were screened. Second, the full texts were evaluated for eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final judgment was made after the group discussion.

Postoperative complications of this study were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification and severe postoperative complications were defined as grades ≥ III[19].

The data of this study were extracted as follows: (1) Studies’ information included the publication year, the first author’s name, country, sample size, study design; (2) patients’ baseline information including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, TMN stage, type of surgery, type of reconstruction, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, cardiovascular system disease, respiratory system diseases, diabetes and renal system diseases; and (3) postoperative complications included operative time, postoperative hospital stay, blood loss, bleeding, time to first flatus(defecation), anastomotic leakage, intestinal obstruction, pulmonary related complication, cardiovascular-related complication, nausea and vomiting, gastric retention, urinary retention, incision infection, urinary tract infection, reoperation, readmission, major complications and mortality.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which had a score ranging from zero to nine points, was used to assess the quality of the enrolled studies[20]. A study with a score of nine points was considered high quality, a study with a score of seven to eight points was considered medium quality, and a study with six or fewer was considered low quality.

The mean differences (MDs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were calculated for continuous variables. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95%CIs were calculated for the postoperative complications. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by using the value of I2 and the result of the chi-squared test. If I2 > 50%, it was considered high heterogeneity, the random effect model was used and P < 0.1 was considered statistically significant[21]. The random effect model was used in this article. Funnel plots and Egger tests were also used to observe the heterogeneity of studies and publication bias. This study was performed with Stata (V.16.0).

There were 70 studies in the database. Twenty-four studies were included in PubMed, 46 studies were included in Embase, and 0 studies were included in Cochrane Library. After deleting duplicate studies and study types that not meet the requirements, 35 studies were left for record screening. Then, browsing the titles and abstracts, leaving 22 studies for full text review. Finally, there were six studies[17,22-26] were included for analysis (Figure 1).

This study consisted by six studies involving 878 participants. These studies were published from 2015 to 2022 and the study period was from 2010 to 2021. There were four retrospective studies and two prospective studies. The NOS scores and baseline characteristics of included studies were summarized in Table 1.

| Ref. | Country | Study date | Study type | Sample size | Years old | Age range | NOS | ||

| ERAS | Conventional | ERAS | Conventional | ||||||

| Xiao et al[17], 2022 | China | 2019-2021 | Prospective | 50 | 50 | 72.7 ± 2.7 | 72.3 ± 2.3 | ≥ 70 | 8 |

| Franceschilli M et al[22], 2022 | Italy | 2013-2021 | Retrospective | 23 | 21 | 69.7 ± 9.8 | 64.3 ± 6.7 | ≥ 18 | 7 |

| Weindelmayer et al[23], 2021 | Italy | 2015-2019 | Retrospective | 248 | 103 | 68 | 70 | 60-78 | 7 |

| Cao S et al[24], 2021 | China | 2014-2018 | Prospective | 85 | 86 | 70.8 ± 3.4 | 71.4 ± 3.7 | 65-85 | 7 |

| Liu et al[25], 2016 | China | 2014-2015 | Retrospective | 42 | 42 | 68.5 ± 4.5 | 69.5 ± 5.4 | ≥ 60 | 8 |

| Bu et al[26], 2015 | China | 2010-2014 | Retrospective | 64 | 64 | 80.1 ± 4.0 | 79.6 ± 3.5 | 45-90 | 8 |

By comparing the clinical characteristics, no significant differences were found in age (MD = 0.06, I2 = 46.03%, 95%CI = -0.18 to 0.30, P = 0.65), sex (OR = 0.95, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.71 to 1.26, P = 0.71), BMI (MD = -0.05, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = -0.22 to 0.12, P = 0.54), smoking (OR = 1.00, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.69 to 1.44, P = 0.98), ASA grade (≥ 2) (OR = 1.03, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.64 to 1.64, P = 0.92), Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) stage II (OR = 1.03, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.69 to 1.54, P = 0.88), TNM stage III (OR = 0.89, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.64 to 1.23, P = 0.47), distal gastrectomy (OR = 1.28, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.74 to 2.22, P = 0.38), proximal gastrectomy (OR = 1.36, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.62 to 2.98, P = 0.44), Billroth-I reconstruction (OR = 1.25, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.59 to 2.67, P = 0.56), Billroth-II reconstruction (OR = 1.17, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.62 to 2.22, P = 0.63), cardiovascular system disease (OR = 1.00, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.72 to 1.39, P = 1.00), respiratory system diseases (OR = 1.04, I2 = 15.67%, 95%CI = 0.62 to 1.73, P = 0.89), Renal system diseases (OR = 0.92, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.47 to 1.82, P = 0.82) and diabetes (OR = 0.73, I2 = 12.29%, 95%CI = 0.48 to 1.12, P = 0.15). We found that the conventional group had more neoadjuvant chemotherapy patients (OR = 2.74, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 1.64 to 4.57, P = 0.00) than the ERAS group (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Studies | Participants (ERAS/conventional) | Odds ratio/mean difference (95%CI) | Heterogeneity |

| Age (yr) | 5 | 264/263 | 0.06 (-0.18, 0.30); P = 0.65 | I2 = 46.03%; P = 0.12 |

| Sex, female | 6 | 512/366 | 0.95 (0.71, 1.26); P = 0.71 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.63 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 5 | 264/263 | -0.05 (-0.22, 0.12); P = 0.54 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.45 |

| Smoking | 2 | 333/189 | 1.00 (0.69, 1.44); P = 0.98 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.62 |

| ASA, ≥2 | 4 | 222/221 | 1.03 (0.64, 1.64); P = 0.92 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.58 |

| TNM stage | ||||

| I | 6 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| II | 6 | 263/215 | 1.03 (0.69, 1.54); P = 0.88 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.81 |

| III | 6 | 399/293 | 0.89 (0.64, 1.23); P = 0.47 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.46 |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Total | 3 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Distal | 3 | 122/126 | 1.28 (0.74, 2.22); P = 0.38 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.97 |

| Proximal | 3 | 69/72 | 1.36 (0.62, 2.98); P = 0.44 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.38 |

| Type of reconstruction | ||||

| Roux-en-Y | 2 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Billroth-I | 2 | 56/58 | 1.25 (0.59, 2.67); P = 0.56 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.40 |

| Billroth-II | 2 | 78/80 | 1.17 (0.62, 2.22); P = 0.63 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.92 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 2 | 271/124 | 2.74 (1.64, 4.57); P = 0.00* | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.45 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Cardiovascular system disease | 4 | 462/316 | 1.00 (0.72, 1.39); P = 1.00 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.86 |

| Respiratory system diseases | 4 | 462/316 | 1.04 (0.62, 1.73); P = 0.89 | I2 = 15.67%; P = 0.31 |

| Renal system diseases | 2 | 333/189 | 0.92 (0.47, 1.82); P = 0.82 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.57 |

| Diabetes | 4 | 462/316 | 0.73 (0.48, 1.12); P = 0.15 | I2 = 12.29%; P = 0.34 |

We found that the ERAS group had shorter postoperative hospital stays (MD = -0.51, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = -0.72 to -0.30, P = 0.00), earlier times to first flatus(defecation; MD = -0.30, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = -0.55 to -0.06, P = 0.02), less intestinal obstruction (OR = 3.24, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 1.07 to 9.78, P = 0.04), less nausea and vomiting (OR = 4.07, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 1.29 to 12.84, P = 0.02), less gastric retention (OR = 5.69, I2 = 2.46%, 95%CI = 2.00 to 16.20, P = 0.00). However, no significant differences were found in operative times (MD = 0.05, I2 = 25.46%, 95%CI = -0.16 to 0.26, P = 0.64), operative blood loss (OR = -0.09, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = -0.36 to 0.17, P = 0.49), postoperative bleeding (OR = 0.47, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.08 to 2.23, P = 0.39), anastomotic leakage (OR = 1.10, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.40 to 3.03, P = 0.86), pulmonary related complication (OR = 0.76, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.43 to 1.35, P = 0.35), cardiovascular-related complication (OR = 0.53, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.25 to 1.11, P = 0.09), urinary retention (OR = 0.68, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.25 to 1.88, P = 0.46), incision infection (OR = 2.26, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.49 to 10.41, P = 0.30), urinary tract infection (OR = 0.52, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.18 to 1.46, P = 0.21), reoperation (OR = 0.46, I2 = 29.68%, 95%CI = 0.07 to 3.00, P = 0.42) and readmission (OR = 1.42, I2 = 47.15%, 95%CI = 0.46 to 4.33, P = 0.54; Table 3).

| Characteristics | Studies | Participants (ERAS/conventional) | Odds ratio/mean difference (95%CI) | Heterogeneity |

| Operative time (min) | 4 | 241/242 | 0.05 (-0.16, 0.26); P = 0.64 | I2 = 25.46%; P = 0.26 |

| Postoperative hospital stays | 10 | 179/177 | -0.51 (-0.72, -0.30); P = 0.00a | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.52 |

| Operative blood loss (mL) | 2 | 108/108 | -0.09 (-0.36, 0.17); P = 0.49 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.41 |

| Postoperative bleeding | 2 | 108/107 | 0.47 (0.08, 2.23); P = 0.39 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.93 |

| Time to first flatus(defecation) | 4 | 129/127 | -0.30 (-0.55, -0.06); P = 0.02a | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.74 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 5 | 470/324 | 1.10 (0.40, 3.03); P = 0.86 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.59 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 3 | 156/156 | 3.24 (1.07, 9.78); P = 0.04a | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.91 |

| Pulmonary related complication | 6 | 512/366 | 0.76 (0.43, 1.35); P = 0.35 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.87 |

| Cardiovascular related complication | 2 | 333/189 | 0.53 (0.25, 1.11); P = 0.09 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.93 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 2 | 106/106 | 4.07 (1.29, 12.84); P = 0.02a | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.52 |

| Gastric retention | 2 | 106/106 | 5.69 (2.00, 16.20); P = 0.00a | I2 = 2.46%; P = 0.31 |

| Urinary retention | 2 | 106/106 | 0.68 (0.25, 1.88); P = 0.46 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.57 |

| Incision infection | 2 | 106/106 | 2.26 (0.49, 10.41); P = 0.30 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.83 |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 | 106/106 | 0.52 (0.18, 1.46); P = 0.21 | I2 = 0.00%; P = 0.86 |

| Reoperation | 3 | 356/210 | 0.46 (0.07, 3.00); P = 0.42 | I2 = 29.68%; P = 0.24 |

| Readmission | 5 | 470/324 | 1.42 (0.46, 4.33); P = 0.54 | I2 = 47.15%; P = 0.11 |

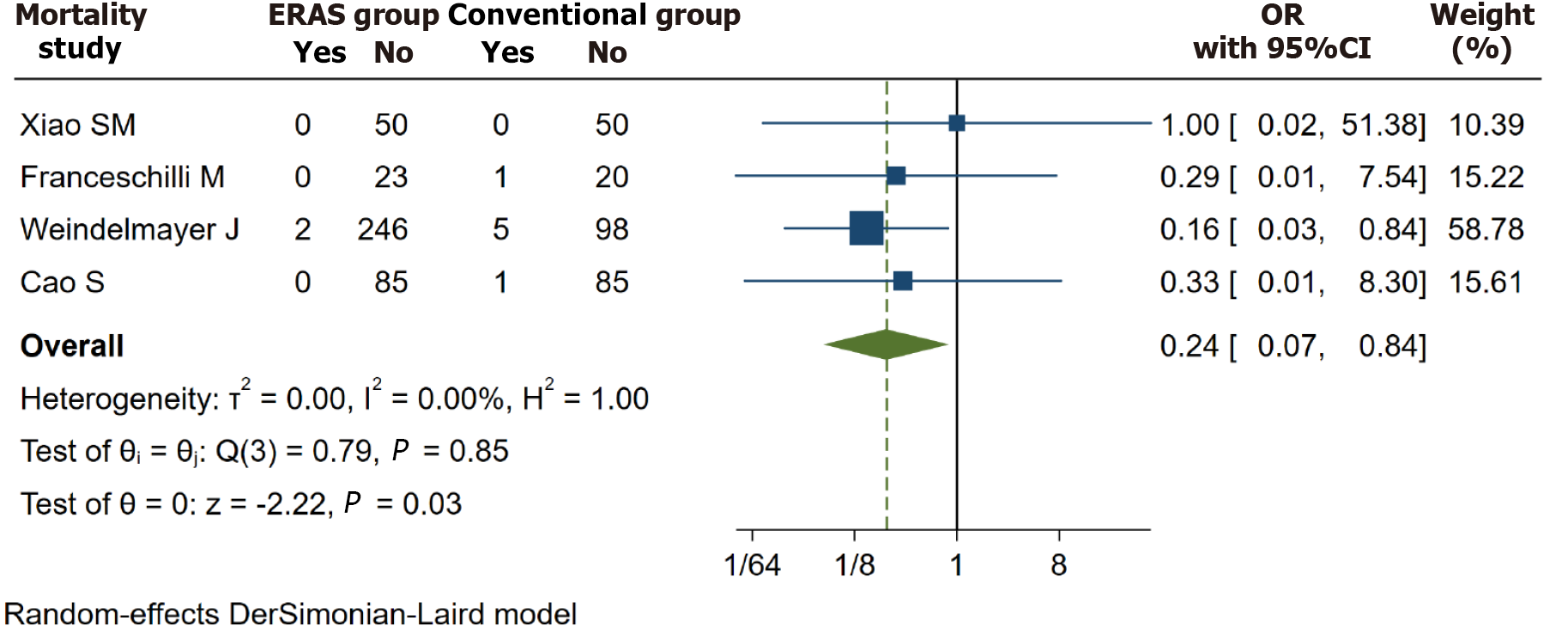

There were four studies[17,22-24] reporting the mortality. After analyzing the data, we found that the conventional group had a greater mortality rate than the ERAS group. (OR = 0.24, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.07 to 0.84, P = 0.03; Figure 2).

There were three studies[17,23,24] reported major complications in elderly patients with GC who underwent surgery. We found that there was no statistically significant difference in the major complications between the ERAS group and the conventional group (OR = 0.67, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.38 to 1.18, P = 0.16; Figure 3).

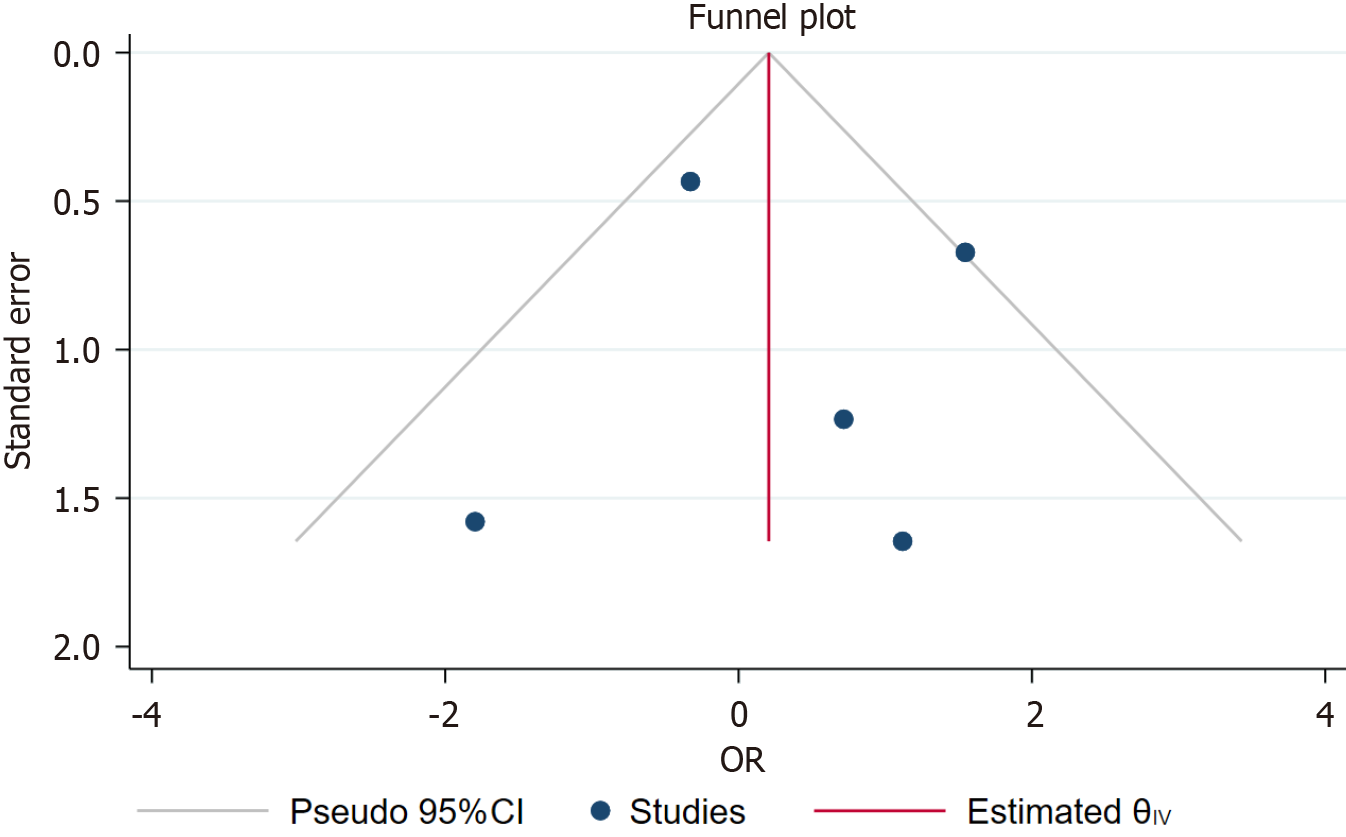

Visual inspection of symmetric funnel plots was used to analyze publication bias for the including studies. A funnel plot was established to reflect the heterogeneity of readmission rates (Figure 4).

This study consists of six studies involving 878 elderly patients who underwent GC surgery. By analyzing the clinical outcomes of the ERAS group and the conventional group, we found that the ERAS group had a lower mortality rate than the conventional group. However, there was no statistically significant difference in major complications between the two groups.

ERAS was gradually developed to strengthen perioperative management and accelerate patients’ postoperative recovery[27]. Recently, ERAS has been successfully applied to patients with a variety of cancers, including colorectal cancer, bladder cancer and GC[28-30]. Due to preexisting physical injuries or associated comorbidities, elderly patients are more likely to experience higher postoperative complication rates and mortality than relatively healthy and younger patients are[31]. For ERAS to be implemented in elderly people, surgeons first follow the principle of safety.

In recent years, many studies have reported the application of ERAS in elderly patients with GC and confirmed its positive effects[17,22-24]. However, there has been no definitive conclusion regarding postoperative mortality. Xiao et al[17] divided elderly cancer patients (aged > 70 years) who underwent GC surgery into an ERAS group and a conventional group. However, no significant difference in mortality was found between the two groups. Similarly, Cao et al[24] reported that there was no significant difference in the mortality rate between the ERAS group and the conventional group in their study. However, Weindelmayer et al[23] held the opposite view. Their research involving elderly patients with GC suggested that the mortality rate in the ERAS group was lower than that in the traditional group. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the specific effect of ERAS on older patients with GC. It was necessary for us to determine whether ERAS could be safely implemented in elderly patients.

Our study showed that the ERAS group had a shorter postoperative hospital stays; earlier time to first flatus(defecation); less intestinal obstruction; less nausea and vomiting; and less gastric retention. And the conventional group had a greater mortality rate than the ERAS group. Our research indicated that the ERAS protocol was safe for elderly patients with GC. However, there was no statistically significant difference in major complications between the two groups. This may have been because elderly patients might have a lower adherence to ERAS measures, which reduces the effectiveness of the protocol[32].

For all we know, this study was the first pooling-up analysis to evaluate the safety of ERAS for elderly patients with GC. This study has several limitations. First, this study only included six articles, which was relatively small. Second, the age range of the elderly individuals included in the study varied. Third, this study lacked certain short-term and long-term outcomes. Fourth, we could not determine the impact of ERAS on younger or ordinary aged patients. Therefore, comprehensive and high-quality randomized controlled trials should be performed to further confirm our findings.

Compared to those with conventional recovery, elderly GC patients who received the ERAS protocol after surgery had a lower risk of mortality. The ERAS protocol was determined to be safe in elderly patients with GC.

This study aimed to evaluate the safety of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) in elderly patients with gastric cancer (GC).

Elderly patients usually have a poor physiological function, more comorbidities, and slow recovery after surgery. Although the application of ERAS protocol in elderly patients with GC has been reported. For elderly patients with GC, there is no convincing evidence that the ERAS protocol is a safe and effective measure.

It was necessary for us to find out whether ERAS could be safely implemented in elderly patients.

The PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases were used to search for eligible studies from inception to April 1, 2023. The mean difference (MD), odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) were pooled for analysis. The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores. We used Stata (V.16.0) software for data analysis.

This study consists of six studies involving 878 elderly patients. By analyzing the clinical outcomes, we found that the ERAS group had shorter postoperative hospital stays (MD = -0.51, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = -0.72 to -0.30, P = 0.00); earlier times to first flatus(defecation; MD = -0.30, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = -0.55 to -0.06, P = 0.02); less intestinal obstruction (OR = 3.24, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 1.07 to 9.78, P = 0.04); less nausea and vomiting (OR = 4.07, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 1.29 to 12.84, P = 0.02); and less gastric retention (OR = 5.69, I2 = 2.46%, 95%CI = 2.00 to 16.20, P = 0.00). Our results showed the conventional group had a greater mortality rate than the ERAS group. (OR = 0.24, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.07 to 0.84, P = 0.03). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the major complications between the ERAS group and the conventional group (OR = 0.67, I2 = 0.00%, 95%CI = 0.38 to 1.18, P = 0.16).

Compared to those with conventional recovery, elderly GC patients who received the ERAS protocol after surgery had a lower risk of mortality.

Compared to those with conventional recovery, elderly GC patients who received the ERAS protocol after surgery was associated with a lower risk of mortality. ERAS protocol was safe in elderly patients with GC.

We acknowledge all of the authors whose publications are referred to in our article.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sugimura H, Japan S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941-1953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3585] [Cited by in RCA: 4893] [Article Influence: 699.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Peng D, Zou YY, Cheng YX, Tao W, Zhang W. Effect of Time (Season, Surgical Starting Time, Waiting Time) on Patients with Gastric Cancer. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1327-1333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim YG, Kong SH, Oh SY, Lee KG, Suh YS, Yang JY, Choi J, Kim SG, Kim JS, Kim WH, Lee HJ, Yang HK. Effects of screening on gastric cancer management: comparative analysis of the results in 2006 and in 2011. J Gastric Cancer. 2014;14:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rahman R, Asombang AW, Ibdah JA. Characteristics of gastric cancer in Asia. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4483-4490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in RCA: 1914] [Article Influence: 239.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Cheng YX, Tao W, Kang B, Liu XY, Yuan C, Zhang B, Peng D. Impact of Preoperative Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on the Outcomes of Gastric Cancer Patients Following Gastrectomy: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Front Surg. 2022;9:850265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Cooke D, Corvera C, Das P, Enzinger PC, Enzler T, Fanta P, Farjah F, Gerdes H, Gibson MK, Hochwald S, Hofstetter WL, Ilson DH, Keswani RN, Kim S, Kleinberg LR, Klempner SJ, Lacy J, Ly QP, Matkowskyj KA, McNamara M, Mulcahy MF, Outlaw D, Park H, Perry KA, Pimiento J, Poultsides GA, Reznik S, Roses RE, Strong VE, Su S, Wang HL, Wiesner G, Willett CG, Yakoub D, Yoon H, McMillian N, Pluchino LA. Gastric Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:167-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 957] [Article Influence: 319.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hu Y, Huang C, Sun Y, Su X, Cao H, Hu J, Xue Y, Suo J, Tao K, He X, Wei H, Ying M, Hu W, Du X, Chen P, Liu H, Zheng C, Liu F, Yu J, Li Z, Zhao G, Chen X, Wang K, Li P, Xing J, Li G. Morbidity and Mortality of Laparoscopic Versus Open D2 Distal Gastrectomy for Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1350-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 530] [Article Influence: 58.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sano T, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, Nashimoto A, Kurita A, Hiratsuka M, Tsujinaka T, Kinoshita T, Arai K, Yamamura Y, Okajima K. Gastric cancer surgery: morbidity and mortality results from a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing D2 and extended para-aortic lymphadenectomy--Japan Clinical Oncology Group study 9501. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2767-2773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002;183:630-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1195] [Cited by in RCA: 1157] [Article Influence: 50.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sugisawa N, Tokunaga M, Makuuchi R, Miki Y, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Terashima M. A phase II study of an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol in gastric cancer surgery. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:961-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Peng D, Cheng YX, Tao W, Tang H, Ji GY. Effect of enhanced recovery after surgery on inflammatory bowel disease surgery: A meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:3426-3435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 13. | Tanaka R, Lee SW, Kawai M, Tashiro K, Kawashima S, Kagota S, Honda K, Uchiyama K. Protocol for enhanced recovery after surgery improves short-term outcomes for patients with gastric cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:861-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cheng YX, Tao W, Liu XY, Yuan C, Zhang B, Zhang W, Peng D. The outcome of young vs. old gastric cancer patients following gastrectomy: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Surg. 2021;21:399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhou Y, Liu S, Wang J, Yan X, Zhang L. Changes in blood glucose of elderly patients with gastric cancer combined with type 2 diabetes mellitus after radical operation and the effect of mediation adjustment for blood glucose on the recovery of gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:4303-4308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kakeji Y, Takahashi A, Hasegawa H, Ueno H, Eguchi S, Endo I, Sasaki A, Takiguchi S, Takeuchi H, Hashimoto M, Horiguchi A, Masaki T, Marubashi S, Yoshida K, Gotoh M, Konno H, Yamamoto H, Miyata H, Seto Y, Kitagawa Y; National Clinical Database. Surgical outcomes in gastroenterological surgery in Japan: Report of the National Clinical Database 2011-2018. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2020;4:250-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xiao SM, Ma HL, Xu R, Yang C, Ding Z. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocol for elderly gastric cancer patients: A prospective study for safety and efficacy. Asian J Surg. 2022;45:2168-2171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52948] [Cited by in RCA: 47144] [Article Influence: 2946.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24805] [Article Influence: 1181.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8858] [Cited by in RCA: 12634] [Article Influence: 842.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ioannidis JP. Interpretation of tests of heterogeneity and bias in meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14:951-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 460] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Franceschilli M, Siragusa L, Usai V, Dhimolea S, Pirozzi B, Sibio S, Di Carlo S. Immunonutrition reduces complications rate and length of stay after laparoscopic total gastrectomy: a single unit retrospective study. Discov Oncol. 2022;13:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Weindelmayer J, Mengardo V, Gasparini A, Sacco M, Torroni L, Carlini M, Verlato G, de Manzoni G. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery can Improve Patient Outcomes and Reduce Hospital Cost of Gastrectomy for Cancer in the West: A Propensity-Score-Based Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:7087-7094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cao S, Zheng T, Wang H, Niu Z, Chen D, Zhang J, Lv L, Zhou Y. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery in Elderly Gastric Cancer Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy. J Surg Res. 2021;257:579-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liu G, Jian F, Wang X, Chen L. Fast-track surgery protocol in elderly patients undergoing laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:3345-3351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bu J, Li N, Huang X, He S, Wen J, Wu X. Feasibility of Fast-Track Surgery in Elderly Patients with Gastric Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1391-1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wilmore DW, Kehlet H. Management of patients in fast track surgery. BMJ. 2001;322:473-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 547] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Taupyk Y, Cao X, Zhao Y, Wang C, Wang Q. Fast-track laparoscopic surgery: A better option for treating colorectal cancer than conventional laparoscopic surgery. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:443-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mortensen K, Nilsson M, Slim K, Schäfer M, Mariette C, Braga M, Carli F, Demartines N, Griffin SM, Lassen K; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Group. Consensus guidelines for enhanced recovery after gastrectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1209-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 505] [Article Influence: 45.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhao G, Cao S, Cui J. Fast-track surgery improves postoperative clinical recovery and reduces postoperative insulin resistance after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lin JX, Yi BC, Yoon C, Li P, Zheng CH, Huang CM, Yoon SS. Comparison of Outcomes for Elderly Gastric Cancer Patients at Least 80 Years of Age Following Gastrectomy in the United States and China. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3629-3638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Liu XR, Liu XY, Zhang B, Liu F, Li ZW, Yuan C, Wei ZQ, Peng D. Enhanced recovery after colorectal surgery is a safe and effective pathway for older patients: a pooling up analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2023;38:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |