Published online Dec 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i12.4738

Revised: October 5, 2024

Accepted: October 22, 2024

Published online: December 15, 2024

Processing time: 104 Days and 11.9 Hours

Pancreatic mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNENs) are rare malignancies affecting the pancreas. The World Health Organization defines MiNENs as neoplasms composed of morphologically recognizable neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components, each constituting 30% or more of the tumor volume. Adenocarcinoma-neuroendocrine carcinoma is the most fre

Here we report a rare case with intermingled components of ductal adenocarcinoma and grade 1 well-differentiated NET in the pancreas. The two tumors show distinct histology and significant differentiation discrepancy (poorly differentiated high grade adenocarcinoma and well-differentiated low grade NET), and also present as metastases in separate lymph nodes. Next generation sequencing of the two components demonstrates KRAS and TP53 mutations in the ductal adenocarcinoma, but no genetic alterations in the NET, suggesting divergent origins for these two components. Although tumors like this meet the diagnostic criteria for MiNEN, clinicians often find the diagnosis and staging confusing and impractical for clinical management.

Mixed NET/non-NET tumors with distinct histology and molecular profiles might be better classified as collision tumors rather than MiNENs.

Core Tip: Pancreatic mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNENs) are rare malignancies affecting the pancreas, recognized by the World Health Organization as neoplasms composed of morphologically recognizable neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components, each constituting ≥ 30% of the tumor volume. However, whether the tumor should be classified as a MiNEN or collision tumor when there is clear divergence in histology and molecular profiles for each component is still debatable. This paper reports a rare case with high grade adenocarcinoma admixed with low grade neuroendocrine tumor in pancreas, which are demonstrated to have distinct molecular profiles. We discuss the potential impacts of tumor classification on staging and clinical management, hoping to encourage more discussions and studies on this rare entity.

- Citation: Zhao X, Bocker Edmonston T, Miick R, Joneja U. Mixed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(12): 4738-4745

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i12/4738.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i12.4738

Pancreatic mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNENs) are rare malignancies affecting the pancreas. They are defined as neoplasms composed of morphologically recognizable neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components, each constituting ≥ 30% of the tumor volume[1]. Though the adenocarcinoma-neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) association is the most frequent, previously termed as mixed adeno-NEC (MANEC) in 2010[1], the spectrum of this entity is wide, and encompasses variable combinations between neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and NECs, and other epithelial tumors of the pancreas (acinar cell carcinoma, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, and serous cystic neoplasm)[1]. Among these, a high grade neuroendocrine component, either small or large cell type, is present in the majority of cases[2], and low grade NET is rarer. Limited molecular studies suggest a clonal relationship between the non-neuroendocrine and neuroendocrine components in these cases[1]. We present a case of mixed ductal adenocarcinoma intermingled with grade 1 well-differentiated NET with discussion of histologic and staging difficulties, molecular profiles, and origins.

A 64-year-old female presented to the emergency department with a three-day history of intermittent abdominal pain.

The patient endorsed stinging left-sided flank pain rated at 10/10 on the pain scale. The patient also reported nausea, vomiting, fevers, and chills. Fever was recorded as high as 40.6 C (105 F) at home. Patient denied chest pain or shortness of breath.

The patient has a past medical history of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus, with long-term current use of insulin.

Other personal history includes fatty liver disease, tobacco use of 1-2 packs a day for about 50 years. No significant family history is noted.

Physical examination revealed a female with normal appearance, not in acute distress, with stable vital signs. There was abdominal tenderness, without guarding or rebound.

Laboratory tests revealed an elevated serum glucose (up to 377 mg/dL, reference range: 70-110 mg/dL), elevated hemoglobin A1c (11.2%, reference range: 4.8%-5.6%), and elevated carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) of 1474 U/mL (reference range: 0-35 U/mL). Pancreatic amylase was within normal limits (40 U/L, 28-100 U/L).

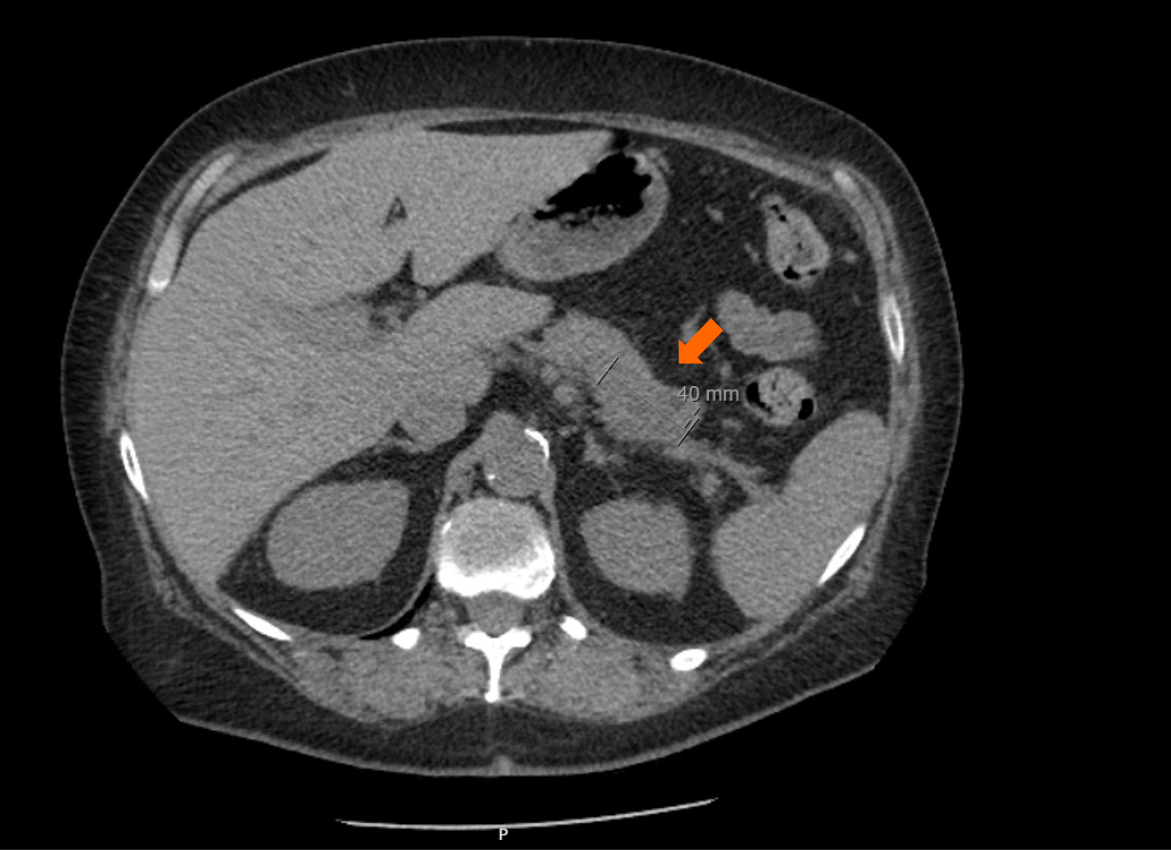

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed a 4.0 cm × 2.0 cm ill-defined, infiltrating mass involving the distal pancreatic body and tail (Figure 1). The mass was diffusely hypoenhancing and demonstrated mild T2 hyperintensity, likely representing central necrosis. The mass encased and occluded the splenic artery and abutted and narrowed the splenic vein which appeared grossly patent. The hepatic arteries, portal vein, and gastroduodenal artery were patent. The findings were highly suspicious for pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and there was no evidence of mesenteric vascular involvement.

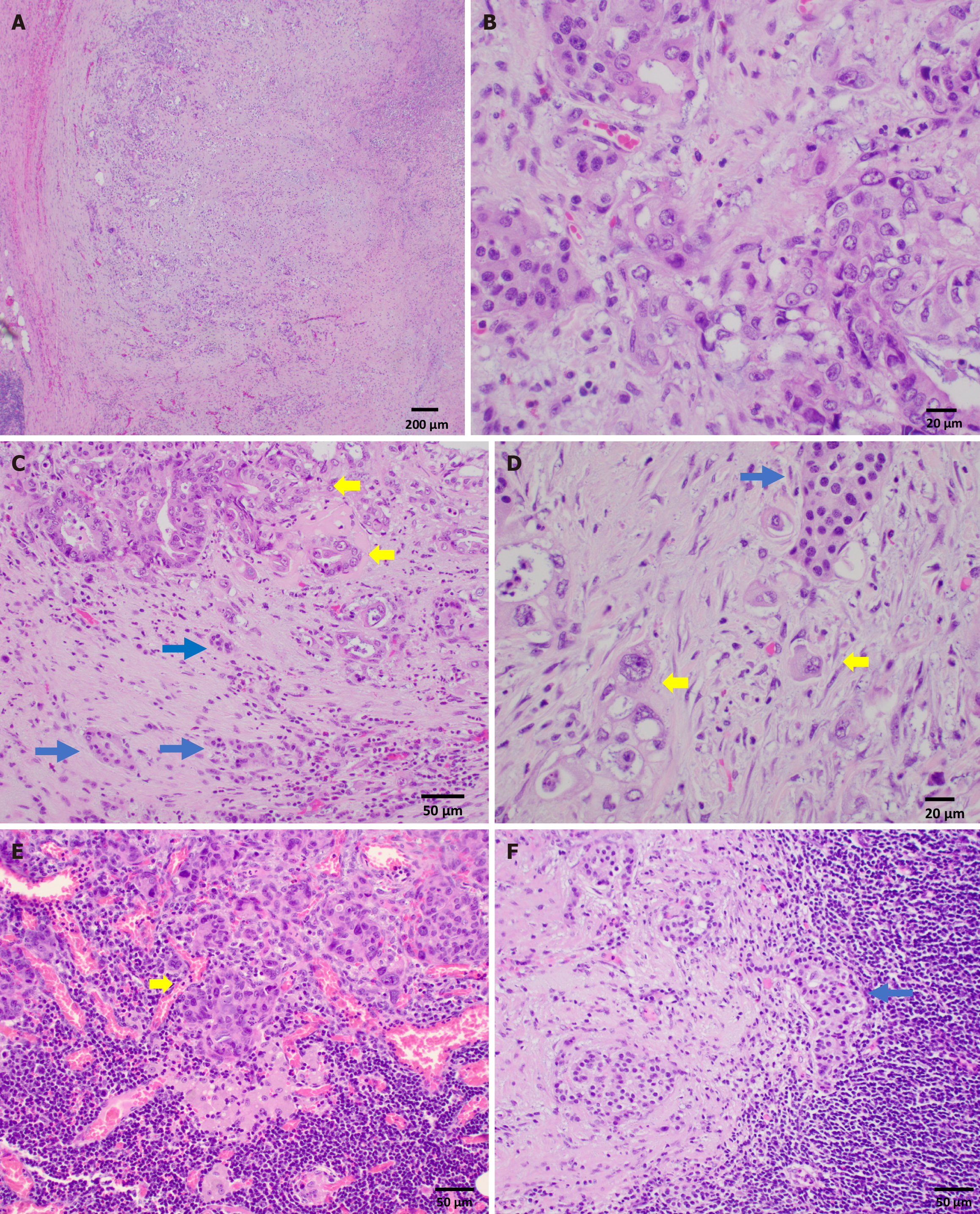

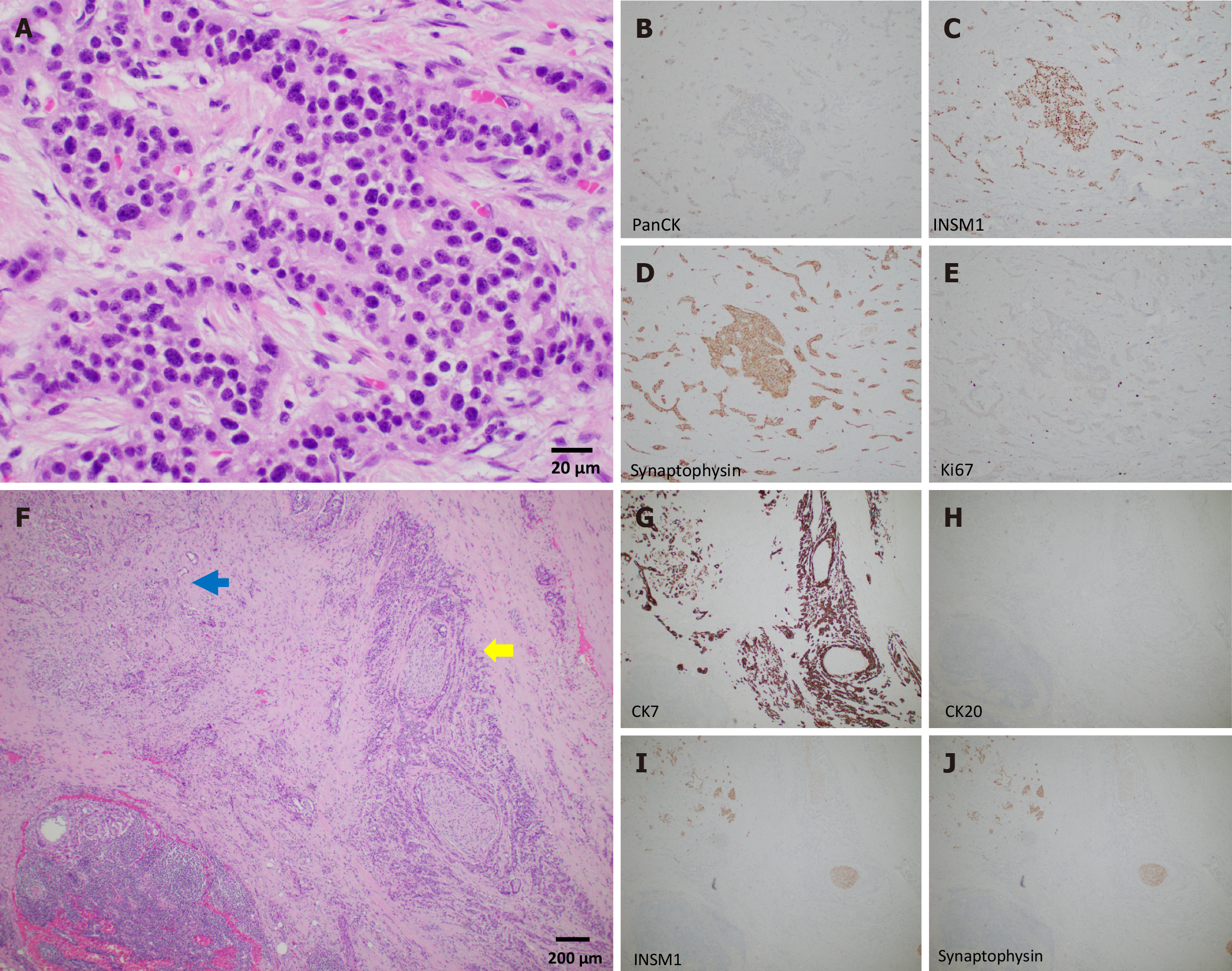

On distal pancreatectomy, a pale-tan ill-defined mass was identified in the pancreatic tail grossly, measuring 3.5 cm × 2.0 cm × 1.5 cm. Histopathologic examination showed a tumor composed of two morphologically distinct yet intermingled components: A moderately to poorly differentiated ductal adenocarcinoma and a low grade well-differentiated NET, grade 1. The ductal adenocarcinoma consisted of cells with high nuclear/cytoplasm ratio, marked nuclear pleomorphism, and vesicular chromatin with prominent nucleoli (Figure 2A and B). Mitotic figures were brisk. Perineural and intravascular invasions were evident. The adenocarcinoma constituted approximately 60% of the tumor mass volume. The neuroendocrine component was comprised of monotonous bland tumor cells with round nuclei, salt-and-pepper chromatin, and abundant cytoplasm arranged in tubules and nests, constituting approximately 40% of the tumor volume (Figure 3A). No mitotic figures were evident in this component. The neuroendocrine component was positive for pan-cytokeratin AE1/AE3, INSM1, and synaptophysin, and Ki67 was < 3% (Figure 3B-E). The overall findings were consistent with a grade 1 well-differentiated NET component (WDNET). In contrast, the adenocarcinoma component was positive for CK7 and negative for CK20, INSM1, and synaptophysin (Figure 3F-J). Regions of intermingled neuroendocrine and ductal components were present (Figure 2C and D; Figure 3F-J). Examination of the lymph nodes revealed adenocarcinoma involving three lymph nodes and metastatic well- differentiated NET in one of a total of twenty-two lymph nodes (Figure 2E and F).

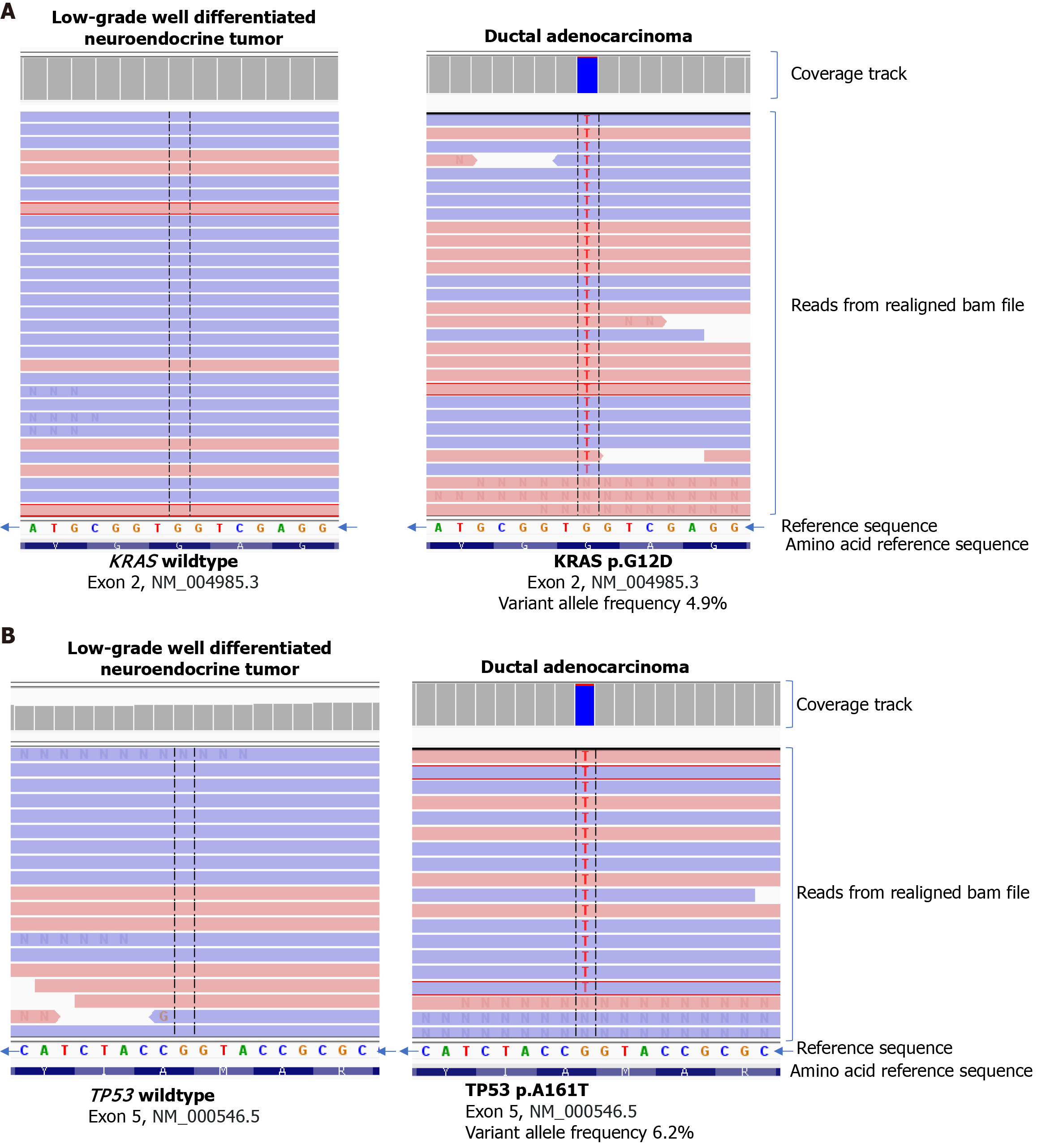

Next generation sequencing of the two different histologic components was performed after microdissection to determine and compare their molecular profiles. The TruSight Tumor 170 panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) analyzes tumor DNA for Single Nucleotide Variants and insertion/deletions in 151 genes and for amplifications of 59 genes and analyzes tumor RNA for fusions and splice variants of 55 genes using the NextSeq 550 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). KRAS exon 2 p.G12D (variant frequency 4.9%) and TP53 exon 5 p.A161T (variant frequency 6.2%) were identified in the adenocarcinoma component. No variants of clinical significance, including KRAS and TP53, were identified for the WDNET (Figure 4). The DNA mismatch repair status by immunohistochemistry in the adenocarcinoma component was intact.

The patient underwent distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy and celiac lymph node dissection, as well adjuvant chemotherapy.

The patient’s postoperative course was remarkable for uncontrolled diabetes, but otherwise uneventful. CA19-9 was trending down from preop level of 1474 U/mL but remained high above 600 U/mL one-month post-surgery and remained persistently elevated. The patient underwent adjuvant chemotherapy for two months.

CT of the chest before surgery demonstrated three small right lung nodules and bilateral groundglass opacities, which have been closely followed. No definitive distant disease was identified on positron emission tomography/CT. After one month into chemotherapy, CT of chest and abdomen revealed enlargement of lung nodules, as well as a new 22 mm hypoechoic intense lesion and two smaller ring-enhancing hypodense lesions in liver. CT-guided fine needle aspiration of one of the liver lesions was consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of pancreatic origin.

The diagnosis of MiNEN, especially a mixed ductal adenocarcinoma and well-differentiated NET, can be difficult to assess histologically. The infiltrative ductal adenocarcinoma glands can cause distortion and isolation of native islet cells that can mimic NET. In our case, the distinguishing feature that lent support to the diagnosis of a superimposed low grade NET component was growth of nests and tubules of monotonous neuroendocrine cells that showed a different morphology than native islets cells. Additionally, the neuroendocrine component was also present in lymph node further confirming their neoplastic nature and metastatic potential. Both tumor components comprised ≥ 30% of the tumor volume and were easily identifiable on routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, meeting the World Health Organization definitional criteria of MiNEN[1].

The pathogenesis of MiNENs represents a matter of open debate amongst pathologists and clinicians. Three main theories have been proposed for MiNENs of the gastrointestinal tract[3,4]: (1) The neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components originate from separate precursor cells independently, either in a synchronous or metachronous manner, and then merge; (2) The two components derive from a common pluripotent stem cell progenitor, then acquires biphenotypic differentiation during carcinogenesis[5-7], supported by findings that common genetic alterations are exhibited in both components; and (3) The two components share a common monoclonal origin but hypothesizes that the neuroendocrine differentiation develops from an initially non-neuroendocrine cell phenotype[4]. Of note, most of these theories were proposed based on studies of mixed neoplasms composed of adenocarcinoma and NEC from gastrointestinal tract. When the endocrine and exocrine tumor components show significant differentiation discrepancies, as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma intermingled with well-differentiated grade 1 NET as in our case, it is of interest to determine whether these two components share the same pluripotent stem cell origin.

In our case, the adenocarcinoma component showed KRAS exon 2 p.G12D and TP53 exon 5 p.A161T mutations, which are well known mutations associated with pancreatic adenocarcinoma carcinogenesis and progression[8,9]. KRAS mutation is believed to be an early event as it is also present in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), and acquisition of mutation in TP53 is associated with PanIN progression and development into invasive adenocarcinoma[10]. The absence of these alterations in the well-differentiated NET in our case suggests that the ductal adenocarcinoma and well-differentiated NET more likely developed from separate origins. Perhaps they are just incidental collision tumors. Few other studies have reported cases of mixed adenocarcinoma and well-differentiated NETs[11-13]; however, most of these studies lack molecular profiling data and no studies have been able to prove any clonal relationship between the two components thus far. Of note, one study showed a case of mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and NET that showed similar molecular alterations in both components (KRAS, GNAS, and CDKN2A mutations, and amplification of CCND1 gene)[14].

The terminology of MiNEN vs collision tumors is very confusing as it is utilized in the current literature. Given that both have overlapping histologic features, it is worth studying whether the difference between MiNENs and collision tumors is that shared molecular profiles are present in MiNENs while not in the latter. This can also create issues during pathologic staging of these tumors. Currently, MiNENs are staged as one tumor type, but it is imperative to mention in the report the individual components present as the spectrum of disease, treatment and prognosis can be wide. Providing percent composition of individual components may also be helpful. While pathologic staging of MiNENs with combined adenocarcinoma and NECs as one T stage based on the size of the whole composite tumor may work just fine, such a system might not be always ideal. For cases like ours, since the more aggressive adenocarcinoma component would be the focus of treatment regimen, perhaps two different tumor templates (pancreas exocrine and endocrine) should be utilized with separate T and N staging for the adenocarcinoma and the low grade NET components. Size determination of these tumors tends to be a challenge because of overlapping morphologic areas and size determination is an important criterion in T-stage determination in both tumor types. Cohort studies with more cases and clinical correlations may provide further information in this arena.

The ductal adenocarcinoma component of our case had several histological features associated with aggressive clinical outcomes, including lymphovascular and perineural invasion, and metastasis to lymph nodes. Although the patient underwent aggressive adjuvant chemotherapy, disease progression with distant metastases occurred sooner than expected for typical pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cases. Whether the presence of the well-differentiated NET played a role in the process of disease progression and/or treatment resistance, either through modifying the tumor microenvironment or crosstalk between tumors, is unknown, and warrants further investigation.

Our case of mixed ductal adenocarcinoma and well-differentiated NET adds to the repertoire of published cases of this entity; however, our case is one of the few that try to address the question of clonal relatedness of the two different histologic components. In contrast to another case report[14], the molecular data shows that the two components in our case have varying molecular profiles based on a 170 gene panel suggesting that these tumors are perhaps best classified as collision tumors rather than MiNENs even though they meet definitional criteria for both. Data from additional cases will benefit the studies of clinical behavior, proper pathologic reporting, as well as optimal therapy of such cases.

| 1. | La Rosa S, Klimstra DS. Pancreatic MiNENs. WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Digestive system tumours. 5th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2019: 370-372. |

| 2. | La Rosa S, Marando A, Sessa F, Capella C. Mixed Adenoneuroendocrine Carcinomas (MANECs) of the Gastrointestinal Tract: An Update. Cancers (Basel). 2012;4:11-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Frizziero M, Chakrabarty B, Nagy B, Lamarca A, Hubner RA, Valle JW, McNamara MG. Mixed Neuroendocrine Non-Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: A Systematic Review of a Controversial and Underestimated Diagnosis. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Bazerbachi F, Kermanshahi TR, Monteiro C. Early precursor of mixed endocrine-exocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: histologic and molecular correlations. Ochsner J. 2015;15:97-101. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Rawdon BB, Andrew A. Origin and differentiation of gut endocrine cells. Histol Histopathol. 1993;8:567-580. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Andrew A, Kramer B, Rawdon BB. The origin of gut and pancreatic neuroendocrine (APUD) cells--the last word? J Pathol. 1998;186:117-118. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Furlan D, Cerutti R, Genasetti A, Pelosi G, Uccella S, La Rosa S, Capella C. Microallelotyping defines the monoclonal or the polyclonal origin of mixed and collision endocrine-exocrine tumors of the gut. Lab Invest. 2003;83:963-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1039-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1500] [Cited by in RCA: 1706] [Article Influence: 155.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Collisson EA, Bailey P, Chang DK, Biankin AV. Molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:207-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 525] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 98.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Taherian M, Wang H, Wang H. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Molecular Pathology and Predictive Biomarkers. Cells. 2022;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang F, Lou X, Qin Y, Xu X, Yu X, Huang D, Ji S. Mixed neuroendocrine nonneuroendocrine neoplasms of the pancreas: a case report and literature review of pancreatic mixed neuroendocrine nonneuroendocrine neoplasm. Gland Surg. 2021;10:3443-3452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nießen A, Schimmack S, Weber TF, Mayer P, Bergmann F, Hinz U, Büchler MW, Strobel O. Presentation and outcome of mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2021;21:224-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Varshney B, Bharti JN, Varshney VK, Yadav T. Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNEN) of pancreas: a rare entity-worth to note. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schiavo Lena M, Cangi MG, Pecciarini L, Francaviglia I, Grassini G, Maire R, Partelli S, Falconi M, Perren A, Doglioni C. Evidence of a common cell origin in a case of pancreatic mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm-neuroendocrine tumor. Virchows Arch. 2021;478:1215-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |