Published online Nov 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i11.4424

Revised: September 17, 2024

Accepted: September 29, 2024

Published online: November 15, 2024

Processing time: 70 Days and 15.3 Hours

Hyperplastic polyps, which represent 30%-93% of all gastric epithelial polyps, are the second most common type of gastric polyps after fundic gland polyps. They were previously considered to have no risk of neoplastic transformation. Recently, an increasing number of cases of gastric hyperplastic polyps (GHPs) combined with neoplastic changes have been reported; however, the specific mechanism underlying their transformation has not been thoroughly explored.

To investigate the clinical, endoscopic, and pathological characteristics of the neoplastic transformation of GHPs and explore the risk factors.

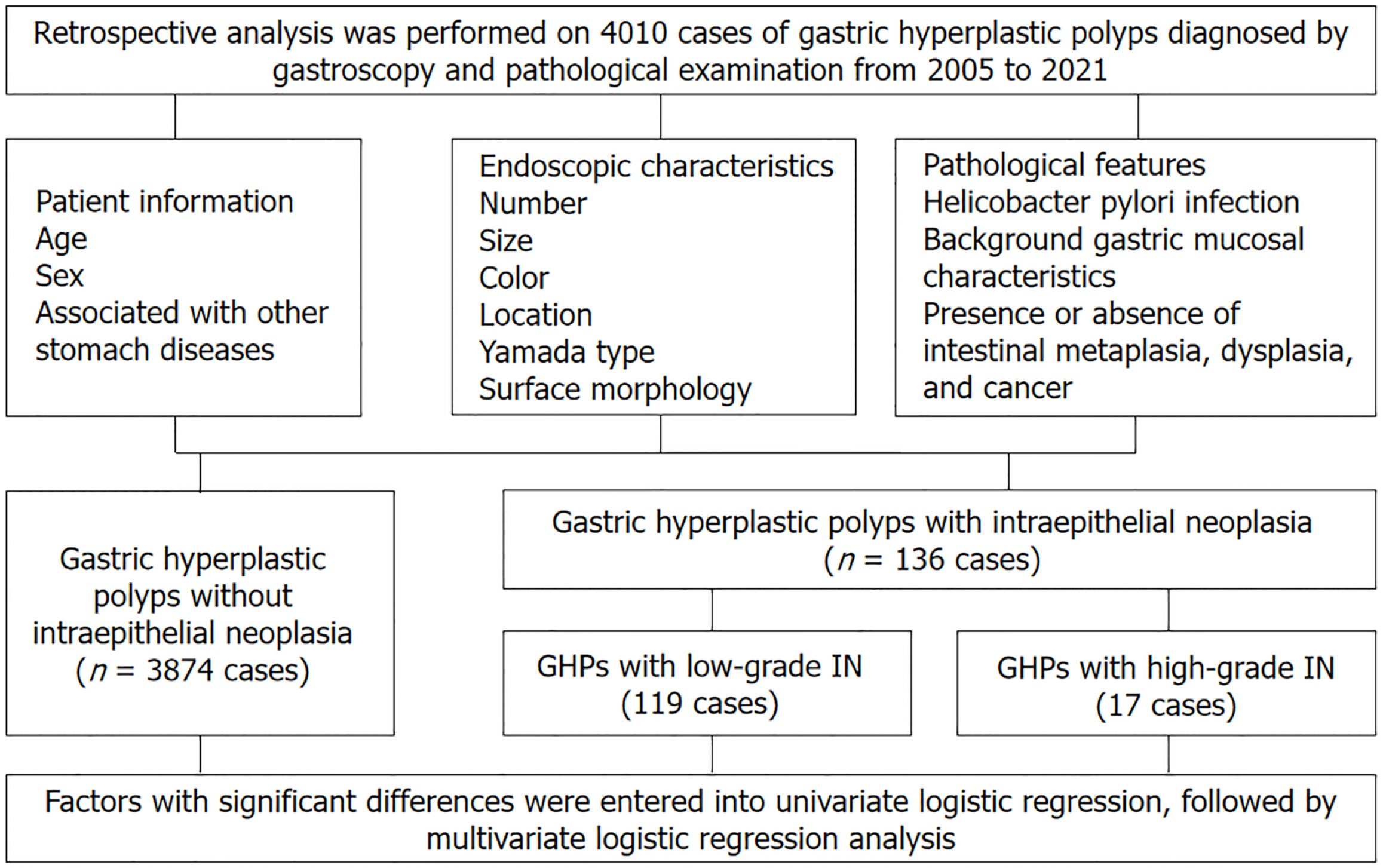

A retrospective analysis was performed on 4010 cases of GHPs diagnosed by ga

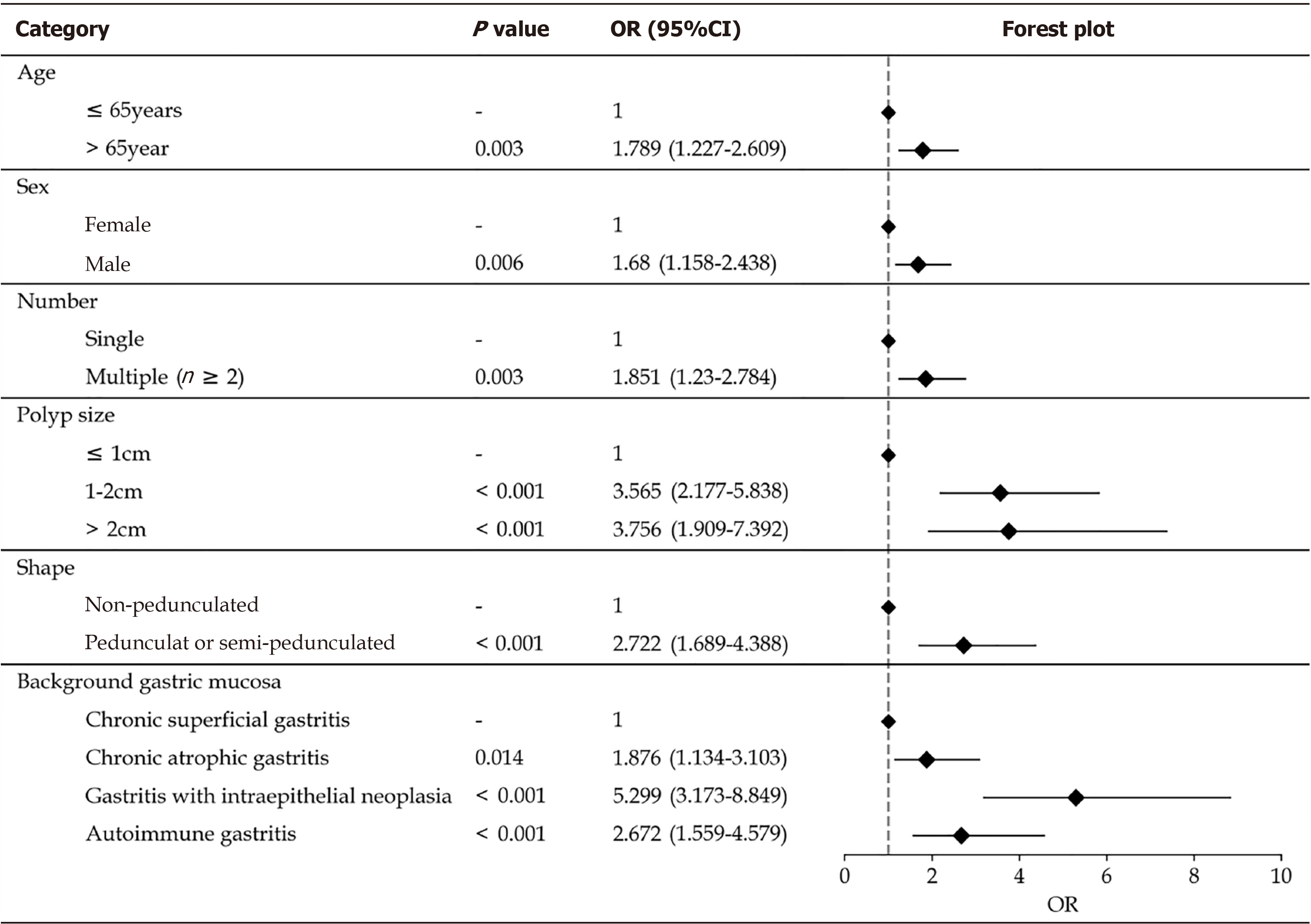

Univariate analysis revealed diameter, multiple polyp presence, redness, rough surface, lobulation, erosion, Yamada classification, location, and gastric mucosa were risk factors for neoplastic transformation. Multivariate analysis showed that age > 65 years [odds ratio (OR) = 1.789; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.227-2.609; P = 0.003], male sex (OR = 1.680; 95%CI: 1.158-2.438; P = 0.006), multiple polyps (OR = 1.851; 95%CI: 1.230-2.784; P = 0.003), pedunculated or semi-pedunculated shape (OR = 2.722; 95%CI: 1.689-4.388; P < 0.001), and polyp diameter were significantly associated with GHPs that demonstrated neoplastic transformation. Compared with chronic superficial gastritis, autoimmune gastritis, atrophic gastritis, and gastritis with IN were independent risk factors for neoplastic transformation [(OR = 2.672; 95%CI: 1.559-4.579; P < 0.001), (OR = 1.876; 95%CI: 1.134-3.103; P = 0.014), and (OR = 5.299; 95%CI: 3.173–8.849; P < 0.001), respectively].

Male sex, age > 65 years, multiple polyps, pedunculated or semi-pedunculated shape, polyp size > 1 cm, and specific background gastric mucosa are key indicators for predicting neoplastic transformation of GHPs.

Core Tip: Our results show that larger diameter, the presence of multiple polyps, pedunculated or semi-pedunculated shape, and specific background gastric mucosa were risk factors for neoplastic transformation. Furthermore, age > 65 years and male sex were important indicators for predicting the risk of malignant transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps. Our findings suggest that for polyps with the abovementioned endoscopic and pathological features, clinicians should be alert to the possibility of neoplastic transformation to improve the diagnosis rate of the neoplastic transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps. Additionally, our study showed that Helicobacter pylori infection was not associated with the risk.

- Citation: Zhang DX, Niu ZY, Wang Y, Zu M, Wu YH, Shi YY, Zhang HJ, Zhang J, Ding SG. Endoscopic and pathological features of neoplastic transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps: Retrospective study of 4010 cases. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(11): 4424-4435

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i11/4424.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i11.4424

Gastric hyperplastic polyps (GHPs) are the second most common type of gastric polyps after fundic gland polyps[1]. They typically do not cause obvious clinical symptoms and were previously considered to have no risk of neoplastic transformation. Recently, an increasing number of reports have emerged on GHPs combined with neoplastic change; however, the specific mechanism has not been thoroughly explored[2,3]. While our understanding of the neoplastic transformation mechanism of GHPs remains limited, knowledge regarding this condition is continuously advancing. Further research will contribute to a better understanding of the development of GHPs and provide more accurate dia

This was a retrospective, single-centre study conducted at Peking University Third Hospital from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2021. All patients were treated by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), or endoscopic forceps removal and were pathologically diagnosed as hyperplastic polyps. The inclusion criteria for patients were age ≥ 18 years, polyp diagnosis based on gastroscopy morphology, and hyperplastic polyp diagnosis based pathology. In contrast, the exclusion criteria were familial adenomatous polyposis, juvenile polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and Cronkhite–Canada syndrome. Ultimately, 4010 cases were enrolled in this study.

The Ethics Committee (No. M2023153) of the Peking University Third Hospital approved this clinical study and its protocol was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was not required from the patients due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Patient information, such as age and sex, was retrospectively collected from medical records. Detailed characteristics, including the location, presence of single or multiple polyps, size, endoscopic appearance of polyp (Yamada’s classification of polyps, mucosal erosion, lobulation, and surface roughness), and pathological features (presence or absence of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma) of polyps were examined. Background gastric mucosal characteristics (chronic superficial gastritis, chronic atrophic gastritis with or without intraepithelial neoplasia, and autoimmune gastritis) were also considered. A skilled pathologist assessed the gastric mucosal background. The location of GHPs in the stomach was classified as the lower third comprising the gastric antrum and angle; the middle third consisting of the lower and mid-body regions of the stomach; and the upper third comprising the fundus, cardia, and high-body of the stomach. Ad

Patients’ basic information, in addition to gastroscopic and histopathological data, was retrospectively analyzed. Ac

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Product and service solutions statistics for windows, version 26.0 (international business machines corporation, Armonk, NY, United States). Normally distributed measurement data are expressed as mean ± SD, and comparisons between groups were made using ordinary analysis of variance and inde

Between 2005 and 2021, 4010 cases of GHPs were confirmed based on gastroscopy and pathological examination at our hospital. Among these, 3874, 119, and 17 cases were in the groups without intraepithelial neoplasia, with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, and with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (5 cases with high-grade dysplasia and 12 with carcinogenesis), respectively. The mean ages of patients in the hyperplastic polyp, low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia groups were 57.86 ± 0.22, 64.49 ± 1.13, and 67.93 ± 2.55 years, respectively. Continuous variables were transformed into grade variables, namely age (≤ 45, 45-65, and > 65 years), revealing sig

| GHPs without IN (n = 3874) | GHPs with IN (n = 136) | χ2 test | Univariate analysis | |||

| χ2 value | P value | P value | OR (95%CI) | |||

| Age (mean ± SD), years | 57.86 ± 0.22 | 64.76 ± 1.04 | 37.178 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.761 (1.459-2.126) |

| ≤ 45 years, n (%) | 699 (18) | 9 (6) | ||||

| 45-65 years, n (%) | 1988 (51) | 54 (40) | ||||

| > 65 years, n (%) | 1187 (31) | 73 (54) | ||||

| Sex, n (%) | 9.057 | 0.011 | 0.003 | 1.672 (1.188-2.356) | ||

| Male | 1423 (37) | 67 (49) | ||||

| Female | 2451 (63) | 69 (51) | ||||

| H. pylori infection, n (%) | 782 (20) | 22 (16) | 1.865 | 0.172 | 0.174 | 0.721 (0.450-1.155) |

| Multiple polyps, n (%) | 1122 (29.4) | 62 (46) | 23.162 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 2.275 (1.614-3.207) |

| Polyp size (mean ± SD), cm | 0.66 ± 0.01 | 203.055 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 3.634 (2.948-4.478) | |

| ≤ 1 cm | 3406 (88) | 66 (48) | ||||

| 1 cm-2 cm | 374 (10) | 53 (39) | ||||

| > 2 cm | 94 (2) | 17 (13) | ||||

| Endoscopic color, n (%) | 18.626 | < 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.671 (0.472-0.972) | ||

| Normal | 2113 (55) | 53 (40) | ||||

| Red | 1488 (40) | 82 (60) | ||||

| White | 275 (5) | 1 (0) | ||||

| Mucosal erosion, n (%) | 289 (8) | 30 (22) | 38.701 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 3.538 (2.318-5.402) |

| Polyp lobulation, n (%) | 185 (5) | 25 (18) | 49.109 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 4.491 (2.840-7.102) |

| Mucosal roughness, n (%) | 864 (22) | 69 (51) | 59.494 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 3.588 (2.542-5.064) |

| Endoscopic classification, n (%) | 169.676 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 2.604 (2.210-3.067) | ||

| I | 2480 (64) | 35 (26) | ||||

| II | 1007 (26) | 42 (31) | ||||

| III | 233 (6) | 27 (20) | ||||

| IV | 155 (4) | 32 (23) | ||||

| Location, n (%) | 23.926 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.750 (1.384-2.212) | ||

| Upper third | 1457 (38) | 31 (23) | ||||

| Middle third | 1715 (44) | 60 (44) | ||||

| Lower third | 702 (18) | 45 (33) | ||||

| Background gastric mucosa, n (%) | 81.877 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.699 (1.472-1.960) | ||

| Autoimmune gastritis | 364 (9.4) | 29 (21) | ||||

| Chronic superficial gastritis | 2466 (64) | 42 (31) | ||||

| Chronic atrophic gastritis | 712 (18) | 31 (23) | ||||

| Gastritis with IN | 332 (9) | 34 (25) | ||||

| Risk factors | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Age | |||

| ≤ 65 years | 1 | ||

| > 65 year | 0.003 | 1.789 | 1.227-2.609 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1 | ||

| Male | 0.006 | 1.680 | 1.158-2.438 |

| Number | |||

| Single | 1 | ||

| Multiple (n ≥ 2) | 0.003 | 1.851 | 1.230-2.784 |

| Polyp size | |||

| ≤ 1 cm | 1 | ||

| 1 cm-2 cm | < 0.001 | 3.565 | 2.177-5.838 |

| > 2 cm | < 0.001 | 3.756 | 1.909-7.392 |

| Endoscopic color-red | 0.701 | 0.916 | 0.619-1.356 |

| Mucosal erosion | 0.271 | 0.75 | 0.454-1.255 |

| Polyp lobulation | 0.264 | 0.73 | 0.432-1.263 |

| Mucosal roughness | 0.128 | 1.38 | 0.912-2.093 |

| Shape | |||

| Non-pedunculated | 1 | ||

| Pedunculated or semi-pedunculated | < 0.001 | 2.722 | 1.689-4.388 |

| Location, n (%) | |||

| Upper third | 1 | ||

| Middle third | 0.066 | 0.609 | 0.368-1.011 |

| Lower third | 0.055 | 1.624 | 0.968-2.724 |

| Background gastric mucosa | |||

| Chronic superficial gastritis | 1 | ||

| Chronic atrophic gastritis | 0.014 | 1.876 | 1.134-3.103 |

| Gastritis with intraepithelial neoplasia | < 0.001 | 5.299 | 3.173-8.849 |

| Autoimmune gastritis | < 0.001 | 2.672 | 1.559-4.579 |

In terms of polyp size, the mean diameters of GHPs without intraepithelial neoplasia, with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, and with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia were 0.66 ± 0.01, 1.25 ± 0.07, and 2.2 ± 0.32 cm, respectively, with significant difference (P < 0.001). Continuous variables were transformed into grade variables, namely polyp size (≤ 1 cm, 1 cm-2 cm, and > 2 cm), revealing significant differences. The diameter of GHPs with intraepithelial neoplasia was significantly larger than in the GHPs group (χ2 = 203.055, P < 0.001), with 82% of GHPs with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia having a diameter of > 1 cm, which was significantly more frequent than in the low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia group (P < 0.05). Among GHPs without intraepithelial neoplasia, 70.6% were mainly single, while the pro

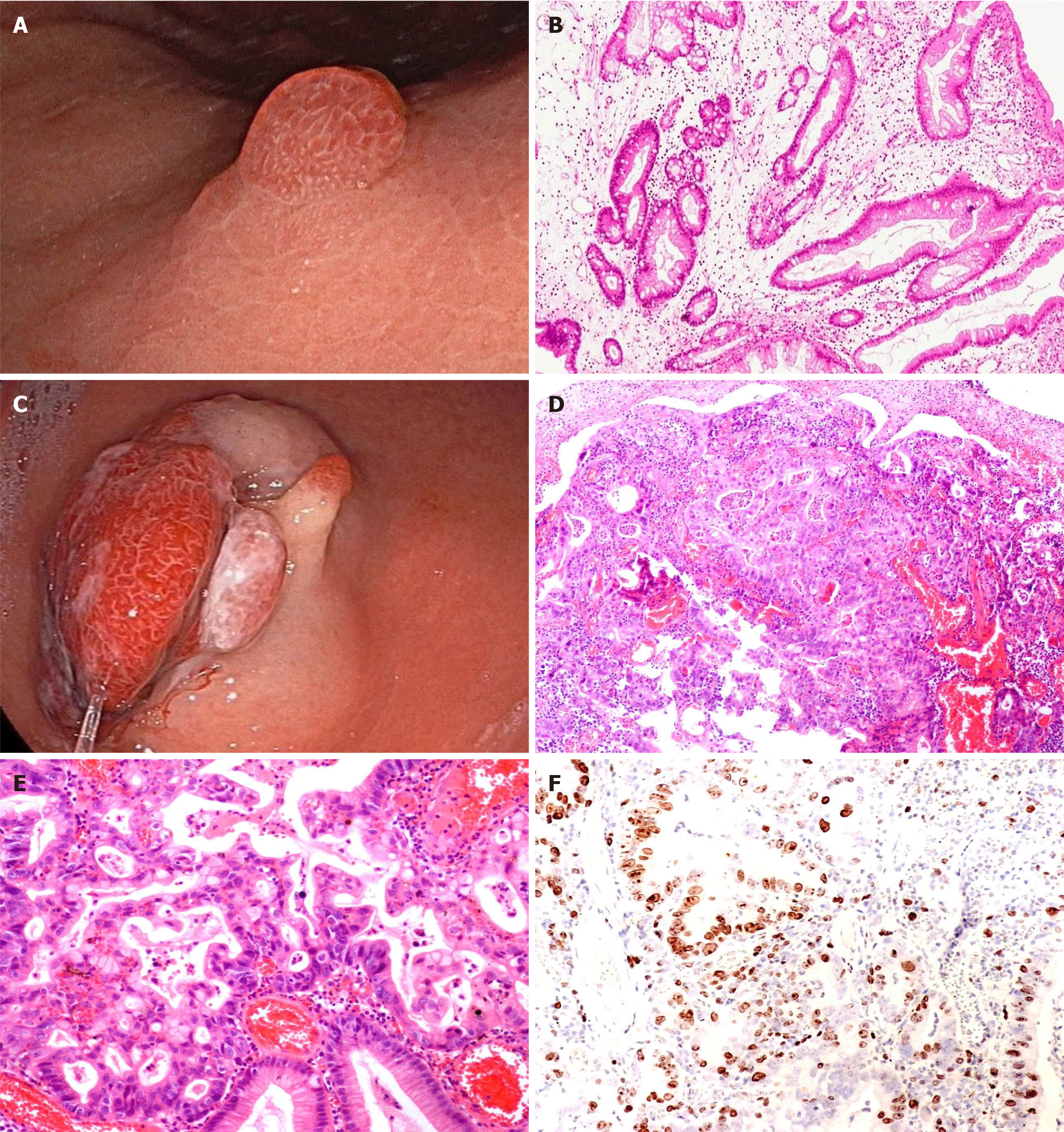

According to Yamada’s classification of polyps, simple GHPs were most commonly classified as Yamada type I (64%), while the proportion of polyps that exhibited intraepithelial neoplasia was significantly reduced, only 26% (χ2 = 169.676, P < 0.001). High-grade intraepithelial neoplasia polyps showed a difference with pedunculated or semi-pedunculated shapes, as Yamada types III and IV classifications accounted for 47% and 41% of these polyps, respectively.

GHPs without intraepithelial neoplasia were observed in the upper and middle third of the stomach (38% and 44%, respectively). Polyps with intraepithelial neoplasia were more likely to occur in the middle and lower third of the stomach (44% and 33%, respectively), with significant differences between the groups (χ2 = 23.926, P < 0.001). Ad

Regarding polyp colour, GHPs without intraepithelial neoplasia were mainly the colour of the surrounding mucosa. The proportion of polyps with redness increased with lesion progression (58% and 76% of polyps in the low-grade and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia groups, respectively), with significant differences (χ2 = 18.626, P < 0.001). Regarding endoscopic morphology, lesion progression was accompanied by mucosal erosion, increased lobulation, and greater surface roughness, with significant differences between the groups (P < 0.001). Further details are presented in Table 1.

We analyzed the pathological results of all polyps. The incidence of polyps with high-grade dysplasia and carcinogenesis was 3.1% (124/4010) and 0.3% (12/4010), respectively. In the analysis of the background gastric mucosa, significant differences were observed between the groups. The background gastric mucosa of GHPs mainly demonstrated chronic superficial gastritis, accounting for 64%. However, in the group with intraepithelial neoplasia, autoimmune gastritis, atrophic gastritis, and gastritis with intraepithelial neoplasia of the surrounding gastric mucosa were present in 21%, 23%, and 25%, respectively, with significant differences (χ2 = 81.877, P < 0.001) (Table 1). Further details are presented in Figure 2.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to explore potential associations between risk factors and the presence of neoplastic transformation in GHPs. Low-grade and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia polyps were combined into one group (GHPs with intraepithelial neoplasia group) and compared with the GHPs without intraepithelial neoplasia group. In the univariate analysis, significant differences were observed in the age and sex of patients, and diameter, endoscopic classification, location, surface morphology (mucosal erosion, lobulation, and surface roughness), and background gastric mucosa of polyps. The differences in these factors between groups were significant (P < 0.05). More specifically, male sex, larger diameter, the presence of multiple polyps, red polyps, rough surface, erosion, and lobulation in the middle third of the stomach, in addition to Yamada type III and IV classifications, with special background gastric mucosa were risk factors for neoplastic transformation. However, no significant difference was observed in terms of H. pylori infection (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Statistically significant risk factors were included in multivariate logistic regression analysis. They were categorised into two groups according to age (< 65 and ≥ 65 years), while polyps with pedunculated or semi-pedunculated shape (corresponding to Yamada type III and IV classifications) were classified into one group and others polyps were categorised into another group (corresponding to Yamada types I and II). The results showed that age > 65 years (OR = 1.789; 95%CI: 1.227-2.609; P = 0.003], male sex (OR = 1.680; 95%CI: 1.158-2.438; P = 0.006), multiple polyps (OR = 1.851; 95%CI: 1.230-2.784; P = 0.003), and pedunculated or semi-pedunculated shape (OR = 2.722; 95%CI: 1.689-4.388; P < 0.001) were significantly associated with GHPs that demonstrated neoplastic transformation. Additionally, polyp diameter was an independent risk factor for harbouring a neoplasm in GHP. Compared with a size of ≤ 1 cm, diameters of 1 cm-2 cm and > 2 cm significantly differed [(OR = 3.565; 95%CI: 2.177-5.838; P < 0.001), (OR = 3.756; 95%CI: 1.909-7.392; P < 0.001), respectively]. Multivariate analysis also showed that specific background gastric mucosa was an independent risk factor for harbouring a neoplasm in GHPs. Compared with chronic superficial gastritis, autoimmune gastritis, atrophic gastritis, and gastritis with intraepithelial neoplasia were significantly different (OR = 2.672; 95%CI: 1.559-4.579; P < 0.001), (OR = 1.876; 95%CI: 1.134-3.103; P = 0.014), and (OR = 5.299; 95%CI: 3.173-8.849; P < 0.001), respectively] (Table 2). Further details are presented in Table 2. We generated a forest map based on independent risk factors, as shown in Figure 3.

GHPs with low-grade and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia were selected for comparison and univariate regression analysis. The result showed that compared with a size of ≤ 1 cm, a diameter of 1 cm-2 cm significantly differed (OR = 6.956; 95%CI: 1.159-41.729; P < 0.05), and pedunculated or semi-pedunculated shape (OR = 7.375; 95%CI: 1.615-33.671; P < 0.05) were significantly associated with GHPs that demonstrated high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. No significant difference was found in other univariate regression analyses between GHPs with low-grade and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, as shown in Table 3.

| GHPs with low-grade IN (n = 119) | GHPs with high-grade IN (n = 17) | χ2 test | Univariate analysis | |||

| χ2 value | P value | P value | OR (95%CI) | |||

| Age (mean ± SD), years | 64.49 ± 1.13 | 67.93 ± 2.55 | 0.6621 | 0.404 | 1.461 (0.600-3.555) | |

| ≤ 45 years, n (%) | 8 (7) | 1 (6) | ||||

| 45-65 years, n (%) | 49 (41) | 5 (30) | ||||

| > 65 years, n (%) | 62 (52) | 11 (65) | ||||

| Sex (male), n (%) | 57 (48) | 10 (59) | 0.710 | 0.399 | 0.402 | 1.544 (0.554-4.355) |

| H. pylori infection, n (%) | 20 (17) | 2 (12) | 0.6541 | 0.655 | 0.702 (0.148-3.322) | |

| Multiple polyps, n (%) | 51 (43) | 11 (65) | 2.035 | 0.154 | 0.542 | 2.133 (0.741-6.145) |

| Polyp size (mean ± SD), cm | 1.25 ± 0.07 | 2.2 ± 0.32 | 16.624 | 0.024 | 0.017 | |

| ≤ 1 cm | 63 (52) | 3 (18) | - | 1 | ||

| 1 cm-2 cm | 46 (39) | 7 (41) | 0.034 | 6.956 (1.159-41.729) | ||

| > 2 cm | 10 (8) | 7 (41) | 0.490 | 1.766 (0.352-8.865) | ||

| Endoscopic color, n (%) | 3.382 | 0.184 | 0.232 | 2.455 (0.826-7.294) | ||

| Normal | 50 (42) | 4 (24) | ||||

| Red | 69 (58) | 13 (76) | ||||

| Mucosal erosion, n (%) | 23 (20) | 7 (41) | 4.403 | 0.051 | 0.224 | 2.891 (0.994-8.411) |

| Polyp lobulation, n (%) | 19 (16) | 6 (35) | 3.704 | 0.054 | 0.086 | 2.781 (0.947-8.703) |

| Mucosal roughness, n (%) | 58 (49) | 11 (65) | 1.517 | 0.218 | 0.237 | 1.928 (0.670-5.552) |

| Endoscopic classification, n (%) | 0.0201 | 0.331 | ||||

| I | 35 (29) | 0 (0) | ||||

| II | 40 (34) | 2 (12) | ||||

| III | 19 (16) | 8 (47) | ||||

| IV | 25 (21) | 7 (41) | ||||

| Shape, n (%) | 8.600 | 0.003 | ||||

| Non-pedunculated | 75 (63) | 2 (12) | - | 1 | ||

| Pedunculated or semi-pedunculated | 44 (37) | 15 (82) | 0.010 | 7.375 (1.615-33.671) | ||

| Location, n (%) | 4.451 | 0.103 | 0.302 | 0.632 (0.316-1.263) | ||

| Upper third | 27 (23) | 4 (24) | ||||

| Middle third | 49 (41) | 11 (65) | ||||

| Lower third | 43 (36) | 2 (12) | ||||

| Background gastric mucosa, n (%) | 0.5531 | 0.644 | 1.788 (0.362-8.388) | |||

| Autoimmune gastritis | 24 (20) | 5 (29) | ||||

| Chronic superficial gastritis | 39 (33) | 3 (18) | ||||

| Chronic atrophic gastritis | 26 (22) | 5 (29) | ||||

| Gastritis with IN | 30 (25) | 4 (24) | ||||

Regarding treatment, the total and curative resection rates of 17 patients with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia were 100% each. These rates are considered to be due to the fact that the cancer focus was mostly located in the polyp, the boundary was clear, and the operation was easy. The postoperative complication rate of ESD and EMR was 0, suggesting that endoscopic treatment was effective.

Gastric polyps are a simple type of stomach polyp that usually cause mucosal damage, most commonly in cases of chronic and autoimmune gastritis caused by H. pylori infection. They are generally considered benign; however, in a few cases, they may progress to dysplasia (0.2%-10%) and adenocarcinoma (0.6%-3%)[2]. The neoplastic transformation of gastric polyps is diagnosed based on the current Nakamura criteria as follows: (1) Benign and neoplastic lesions coexist in the same polyp; (2) Sufficient evidence indicates that the benign part has the characteristics of benign polyps, and (3) The neoplastic part has obvious cellular and structural atypia[3]. In this study, the tissue carcinogenesis rate of GHPs was 0.3%, and the probability of concurrent dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia occurrence was 3.1% and 5%, respectively, which is broadly consistent with previous findings[4].

Regarding clinical features, the incidence of GHPs increased with age. The mean age of the patients in this study was 58 years, of which 45-65 years were the age groups with the highest incidence (51%). Furthermore, the incidence of GHPs was higher in females (63%). We observed significant differences in the age and sex of patients among the groups. The probability of neoplastic transformation of polyps increased with older age, whereas the proportion of neoplastic tran

Regarding the endoscopic features, an increasing number of reports have recently emerged on GHPs combined with neoplastic changes. A polyp size of > 1 cm is considered a risk factor for neoplastic transformation[3]. The erosive mor

Furthermore, the relationship between H. pylori infection and GHPs remains unclear. A large database study in the United States showed that the rate of H. pylori infection in the hyperplastic polyp group was lower than that in the control group[7]. However, considering the factors influencing the background gastric mucosa and the possibility of previous eradication of H. pylori infection is essential in the treatment of hyperplastic polyps[8]. The British gastroenterological of society strongly recommends the eradication of H. pylori in patients with hyperplastic polyps and endoscopic follow-up after 3-6 months of treatment[9]. H. pylori is considered a carcinogen of gastric cancer; however, in our study on the neo

GHPs are usually associated with inflammatory lesions of the local gastric mucosal tissue, particularly long-standing H. pylori infection-associated gastritis and autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis[4], which are used as markers of an abnormal background gastric mucosa rather than an isolated pre-neoplastic lesion. According to Orlowska et al[10], the risk of developing neoplastic tumours in the gastric mucosa outside the polyps is slightly higher than that in the polyps. Markowski et al[4] reported a 7.1% chance of neoplastic transformation of the mucosa around the gastric polyp, whereas the polyp was neoplastic with a conversion rate of 2.1%.

In our study, multivariate analysis showed that specific background gastric mucosa was an independent risk factor for harbouring a neoplasm in GHPs. Compared with chronic superficial gastritis, autoimmune gastritis, atrophic gastritis, and gastritis with intraepithelial neoplasia were significantly different [(OR = 2.672; 95%CI: 1.559-4.579; P < 0.001), (OR = 1.876; 95%CI: 1.134-3.103; P = 0.014), and (OR = 5.299; 95%CI: 3.173-8.849; P < 0.001), respectively] (Table 2). In the high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia group, chronic atrophic gastritis with intraepithelial neoplasia accounted for 24% of cases (4/17), of which two were cases of gastric cancer. Autoimmune gastritis in the background gastric mucosa accounted for 29% of cases (5/17) in the high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia group, which is consistent with previous studies showing that patients with autoimmune gastritis are prone to polyp. Although the mechanism remains unclear, some studies suggest that it is related to mucosal atrophy or hypergastrinemia blood syndrome[11]. In Japan, a case of hyperplastic polyp carcinogenesis with submucosal and lymphatic invasion occurring on the basis of gastritis has been reported[12]. Therefore, the association between the background gastric mucosa and hyperplastic polyps should be emphasised in the clinical diagnosis of gastric polyps, and an adequate biopsy of the surrounding mucosa is recommended to evaluate any underlying gastric disease[13].

Studies have shown that cancers associated with GHPs are highly differentiated. Among the 17 patients in our study, except for 5 cases of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, the rest were differentiated cancers. Four cases were tubular adenocarcinoma, and one was papillary adenocarcinoma, all of which were differentiated adenocarcinomas. However, the remaining seven cases could not be conclusively diagnosed with a specific pathological type, and no poorly differentiated or undifferentiated cancers were found. These findings align with the results of previous literature and are also comparable to those reported in other studies. Of these cases, immune combination analysis revealed that two cases were caudal type homeobox (CDX)-2 (-) and one was CDX-2 (+). Currently, the exact mechanism underlying the carcinogenesis of hyperplastic polyps remains unclear. Previous studies have suggested that the most simple tissue type of hyperplastic polyps is differentiated adenocarcinoma[14]. A small number of poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas have been re

This study has some limitations. First, the overall number of carcinogenesis cases in this study was small. Therefore, further expanding the sample size is necessary for more in-depth research to explore the risk factors for neoplastic transformation. Other limitations of the study include its single-center and retrospective design. Additionally, basic experiments such as specific immunohistochemical experiments or analyses of gene expression are needed to further explore the specific mechanisms underlying the carcinogenesis of hyperplastic polyps. However, the overall sample size of this study was large, and we believe that the results will contribute to the clinical treatment of GHPs.

GHPs pose a risk of neoplastic transformation; however, the mechanism remains unclear and needs to be further ex

| 1. | Kővári B, Kim BH, Lauwers GY. The pathology of gastric and duodenal polyps: current concepts. Histopathology. 2021;78:106-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Salomao M, Luna AM, Sepulveda JL, Sepulveda AR. Mutational analysis by next generation sequencing of gastric type dysplasia occurring in hyperplastic polyps of the stomach: Mutations in gastric hyperplastic polyps. Exp Mol Pathol. 2015;99:468-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Han AR, Sung CO, Kim KM, Park CK, Min BH, Lee JH, Kim JY, Chang DK, Kim YH, Rhee PL, Rhee JC, Kim JJ. The clinicopathological features of gastric hyperplastic polyps with neoplastic transformations: a suggestion of indication for endoscopic polypectomy. Gut Liver. 2009;3:271-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Markowski AR, Markowska A, Guzinska-Ustymowicz K. Pathophysiological and clinical aspects of gastric hyperplastic polyps. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8883-8891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Hu H, Zhang Q, Chen G, Pritchard DM, Zhang S. Risk factors and clinical correlates of neoplastic transformation in gastric hyperplastic polyps in Chinese patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10:2582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | João M, Areia M, Alves S, Elvas L, Taveira F, Brito D, Saraiva S, Teresa Cadime A. Gastric Hyperplastic Polyps: A Benign Entity? Analysis of Recurrence and Neoplastic Transformation in a Cohort Study. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2021;28:328-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sonnenberg A, Genta RM. Prevalence of benign gastric polyps in a large pathology database. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:164-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nam SY, Park BJ, Ryu KH, Nam JH. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the regression of gastric polyps in National Cancer Screening Program. Korean J Intern Med. 2018;33:506-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goddard AF, Badreldin R, Pritchard DM, Walker MM, Warren B; British Society of Gastroenterology. The management of gastric polyps. Gut. 2010;59:1270-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Orlowska J, Jarosz D, Pachlewski J, Butruk E. Malignant transformation of benign epithelial gastric polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2152-2159. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hu HY, Ji M, Chen GY, Zhang ST. [The association of gastric hyperplastic polyps and autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis]. Zhonghua Xiaohuaneijing Zazhi. 2020;37:573-577. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Yamanaka K, Miyatani H, Yoshida Y, Ishii T, Asabe S, Takada O, Nokubi M, Mashima H. Malignant transformation of a gastric hyperplastic polyp in a context of Helicobacter pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Marcos-Pinto R, Areia M, Leja M, Esposito G, Garrido M, Kikuste I, Megraud F, Matysiak-Budnik T, Annibale B, Dumonceau JM, Barros R, Fléjou JF, Carneiro F, van Hooft JE, Kuipers EJ, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:365-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 712] [Cited by in RCA: 670] [Article Influence: 111.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Forté E, Petit B, Walter T, Lépilliez V, Vanbiervliet G, Rostain F, Barsic N, Albeniz E, Gete GG, Gabriel JCM, Cuadrado-Tiemblo C, Ratone JP, Jacques J, Wallenhorst T, Subtil F, Albouys J, Giovannini M, Chaussade S, Landel V, Ponchon T, Saurin JC, Barret M, Pioche M. Risk of neoplastic change in large gastric hyperplastic polyps and recurrence after endoscopic resection. Endoscopy. 2020;52:444-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Imura J, Hayashi S, Ichikawa K, Miwa S, Nakajima T, Nomoto K, Tsuneyama K, Nogami T, Saitoh H, Fujimori T. Malignant transformation of hyperplastic gastric polyps: An immunohistochemical and pathological study of the changes of neoplastic phenotype. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1459-1463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Terada T. Malignant transformation of foveolar hyperplastic polyp of the stomach: a histopathological study. Med Oncol. 2011;28:941-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |