Published online Sep 15, 2023. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v15.i9.1616

Peer-review started: June 30, 2023

First decision: July 24, 2023

Revised: July 24, 2023

Accepted: August 4, 2023

Article in press: August 4, 2023

Published online: September 15, 2023

Processing time: 75 Days and 0 Hours

The multidisciplinary team (MDT) has been carried out in many large hospitals now. However, given the costs of time and money and with little strong evidence of MDT effectiveness being reported, critiques of MDTs persist.

To evaluate the effects of MDTs on patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases and share our opinion on management of synchronous colorectal liver metastases.

In this study we collected clinical data of patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases from February 2014 to February 2017 in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital and subsequently divided them into an MDT+ group and an MDT- group. In total, 93 patients in MDT+ group and 169 patients in MDT- group were included totally.

Statistical increases in the rate of chest computed tomography examination (P = 0.001), abdomen magnetic resonance imaging examination (P = 0.000), and preoperative image staging (P = 0.0000) were observed in patients in MDT+ group. Additionally, the proportion of patients receiving chemotherapy (P = 0.019) and curative resection (P = 0.042) was also higher in MDT+ group. Multiva

These results proved that MDT management did bring patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases more opportunities for comprehensive examination and treatment, resulting in better outcomes.

Core Tip: Synchronous colorectal liver metastases usually predict a poor prognosis. Nevertheless, given the costs of time and money and with little strong evidence of multidisciplinary team (MDT) effectiveness being reported, critiques of MDTs still persist. This study demonstrates that MDT management brings patients more opportunities for aggressive examination and treatment. Retrospective clinical data shows that the population of patients assessed by MDT meetings has higher 1-year and 5-year overall survival.

- Citation: Li H, Gu GL, Li SY, Yan Y, Hu SD, Fu Z, Du XH. Multidisciplinary discussion and management of synchronous colorectal liver metastases: A single center study in China. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2023; 15(9): 1616-1625

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v15/i9/1616.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v15.i9.1616

Colorectal cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer, with an estimated 1.78 million cases occurring in 2020[1]. About 50% of patients with colorectal cancer will suffer distant metastases; the liver is the most common site. In particular synchronous liver metastases account for 15%-25% of colorectal liver metastases[2]. Synchronous colorectal liver metastases are usually defined as liver metastases detected at or before primary colorectal cancer. Curative resection is identified as the most effective method for curing synchronous colorectal liver metastases. However, data showed only 5%-15% patients with synchronous liver metastases were curable with resection[3,4], 5-year survival rates of patients with unresectable liver metastases were starkly lower, at less than 5% respectively[5].

The multidisciplinary team (MDT) originated in the United Kingdom in the 1960s and 1970s[6] and is defined as a regularly scheduled discussion of patients, especially those diagnosed with cancer, comprising professionals from different specialties[7]. After years of development, MDTs have been used in most large hospitals and are recommended by most guidelines on cancer therapy[8]. Nevertheless, given the costs of time and money and with little strong evidence of MDT effectiveness being reported, critiques of MDTs persist[9,10].

On a positive note, many retrospective and prospective studies have already provided clinical evidence in favor of MDT meetings with regard to diagnosis, tumor staging, treatment strategy, and oncological outcomes of cancer including colorectal cancers[11-13]. However, few reports have shown the impact of MDT meetings on synchronous colorectal liver metastases. In this study, we undertook a retrospective analysis of the impact of MDT meetings on the clinical data of patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases, and we provide our insights on management of synchronous colorectal liver metastases in an MDT model.

This retrospective study incorporated patients who were diagnosed with synchronous colorectal liver metastases from February 2014 to February 2017 in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital. All patients in the MDT group (MDT+) were discussed by the gastrointestinal cancer MDT of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital and had thorough records in minutes of the meetings. Patients without discussion at MDT meetings (MDT-) were treated by doctors with equivalent qualifications of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital. This study received approval from the ethics commission of the General Hospital of People’s Liberation Army.

Patients with uncertain diagnoses and medical records were excluded, as were patients suffering from extrahepatic metastases or other severe disease that might affect survival time seriously. These patients were followed up for 66 mo in this study. A total of 169 patients in MDT- group (80 men and 89 women; mean age: 60.15 years) and 93 patients in MDT+ group (53 men and 40 women; mean age: 59.19 years) were ultimately included in this study.

To analyze the impact of MDT on overall survival (OS), we compiled the following items in our data collection according to previous studies[14-17]: (1) Demographic data: Age, gender, body mass index; (2) Cancer characteristics: Site of primary tumor, primary lymph node (LN) involvement, multiple liver metastases, extrahepatic metastases; (3) Baseline examination including imaging data and serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels; (4) Detailed data about chemotherapy and surgery; and (5) Clinical data of follow-up until patients’ death or the end of the follow-up period (August 2022). Data were mainly collected from the Electronic Medical Record of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital, and those unavailable in the Electronic Medical Record were obtained from patients, in the form of copied records, imaging and laboratory data.

Continuous data are presented as median (range) unless indicated otherwise. Comparisons of differences in continuous variables between the two groups were performed with student’s t test. Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact method were carried out for categorical data. In the analysis of event-specific rates, patients were considered to be at risk of the studied event until death or the end of follow-up. Cumulative survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method and statistically compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate survival analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model, with results presented as a hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Univariate and multivariate logistic analysis was performed using the likelihood ratio test, with results presented as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95%CI. Multivariate analysis included items with univariate analysis results of P < 0.20. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences 26.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

A total of 262 patients were included in this study. The clinical characteristics of patients are detailed in Table 1. In MDT+ group, a significant 80.65% of patients (75 out of 93) were diagnosed with liver metastases at more than one site. Interestingly, the proportion of patients in MDT- group was 79.88% (P = 0.989). No significant differences in demographic data and cancer characteristics were observed between these two groups.

| Characteristics | MDT+ (n = 93) | MDT- (n = 169) | P value |

| Age (yr), mean (min-max) | 59.19 (28.00-89.00) | 60.15 (25.00-92.00) | 0.605 |

| Male/female, n | 40/53 | 89/80 | 0.172 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (min-max) | 24.83 (17.29-33.82) | 23.62 (16.06-33.5) | 0.221 |

| KPs score ≥ 60 | 89/12 | 150/19 | 0.095 |

| Adenocarcinoma/mucinous adenocarcinoma, n | 83/10 | 143/26 | 0.393 |

| Poor differentiation, n (%) | 16 (17.20) | 21 (12.43) | 0.380 |

| Primary tumor category ≥ T3, n (%) | 67 (72.04) | 135 (79.88) | 0.197 |

| Primary LN involvement, n (%) | 60 (64.52) | 118 (69.82) | 0.458 |

| Multiple liver metastases, n (%) | 75 (80.65) | 134 (79.29) | 0.920 |

The rate of chest computed tomography (CT) examination in patients in MDT+ group was significantly higher than that in MDT- group (100% vs 82.84%, P = 0.001). This trend was mirrored in the rate of abdomen magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (100% vs 73.96%, P = 0.000). As radiological tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging was routinely required in our gastrointestinal cancer MDT meeting, all patients in MDT+ group had been diagnosed with TNM staging. However, only 20.12% of patients were evaluated with radiological TNM staging in MDT- group (P = 0.000). No significant difference in positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) between the two groups was observed (P = 0.906). Baseline imaging exami

| MDT+ (n = 93) | MDT- (n = 169) | P value | |

| Chest CT, n (%) | 93 (100) | 140 (82.84) | 0.001 |

| Abdomen MRI, n (%) | 89 (95.70) | 125 (73.96) | 0.000 |

| PET-CT, n (%) | 22 (23.66) | 47 (27.81) | 0.906 |

| TNM staging, n (%) | 93 (100) | 34 (20.12) | 0.000 |

Of 17 patients in MDT+ group were diagnosed with initial resectable synchronous colorectal liver metastases. 77 patients in the MDT+ group and 116 patients in MDT- group received chemotherapy (82.80% vs 68.64%, P = 0.0191). Approximately 10% of these chemotherapy patients were successfully converted to be radically resectable after several chemotherapy cycles. At the end of the follow-up period, 30 patients in MDT+ group and 35 patients in MDT- group had undergone curative resection (32.29% vs 20.71%, P = 0.0415). Statistical differences were not observed in the proportion of initial resectable liver metastases, and successful conversion chemotherapy between the two groups. Oncology treatment and surgery is outlined in Table 3.

| MDT+ (n = 93) | MDT- (n = 169) | P value | |

| Initial resectable, n (%) | 17(18.285) | 21 (12.43) | 0.270 |

| Successful conversion chemotherapy, n (uninitial resectable, n) | 13 (761) | 14 (1481) | 0.148 |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | 77 (82.80) | 116 (68.64) | 0.019 |

| Curative resection, n (%) | 30 (32.29) | 35 (20.71) | 0.042 |

| Simultaneous resection, n (%) | 29 (97.63) | 19 (55.88) | 0.001 |

| RFA, n (%) | 5 (16.67) | 15 (44.12) | 0.036 |

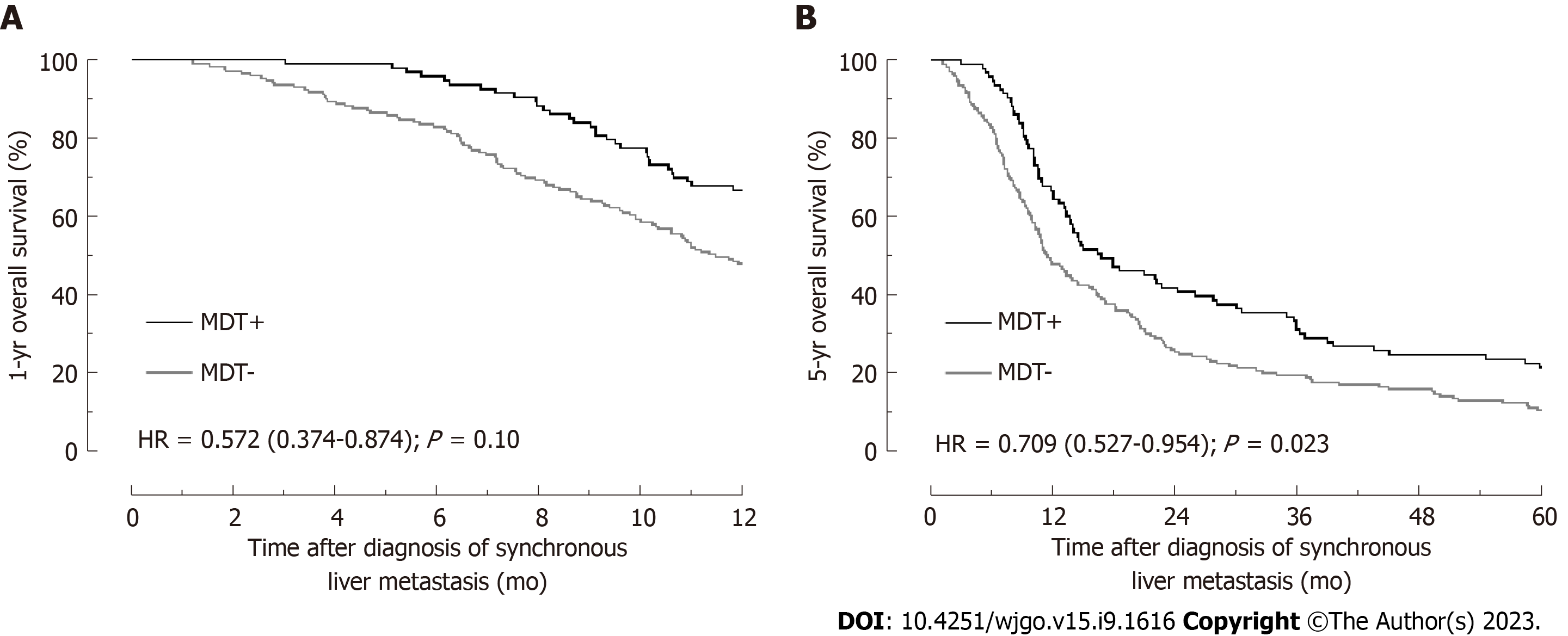

The 1-year OS rate of all 262 patients was determined to be 54.58%. There was a significant difference between the two groups, with patients in MDT+ group demonstrating statistically higher 1-year OS rates than those in MDT- group (66.67% vs 47.93%; P = 0.0036, Figure 1). Univariate analysis employing the Cox proportional hazards model, age > 75 years, CEA > 5 ng/mL, primary LN involvement, multiple liver metastases, extrahepatic metastases, curative resection, MDT, and chemotherapy were associated with 1-year OS rates at P < 0.20 (Table 4).

| n (%) | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Age > 75 | 61 (23.28) | 3.533 | 2.44-5.11 | 0.000 | 2.065 | 1.257-3.393 | 0.004 |

| Sex (male) | 133 (50.76) | 0.845 | 0.590-1.211 | 0.358 | |||

| BMI > 28 | 46 (17.56) | 0.765 | 0.468-1.250 | 0.285 | |||

| CEA > 5 ng/mL | 125 (47.71) | 7.296 | 4.674-11.391 | 0.000 | 5.308 | 3.262-8.638 | 0.000 |

| Colon primary | 118 (45.04) | 1.283 | 0.896-1.838 | 0.174 | 1.058 | 0.724-1.544 | 0.772 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 36 (13.74) | 0.863 | 0.502-1.482 | 0.593 | |||

| Poor differentiation | 37 (14.12) | 1.282 | 0.793-2.073 | 0.311 | |||

| Primary tumor category ≥ T3 | 202 (77.10) | 1.284 | 0.820-2.009 | 0.274 | |||

| Primary LN involvement | 178 (67.94) | 3.336 | 2.061-5.400 | 0.000 | 1.948 | 1.156-3.281 | 0.012 |

| Multiple liver metastases | 210 (80.15) | 13.97 | 4.44-43.97 | 0.000 | 4.747 | 1.470-15.333 | 0.009 |

| MDT | 93 (35.50) | 0.53 | 0.353-0.801 | 0.003 | 0.572 | 0.374-0.874 | 0.010 |

| chemotherapy | 193 (73.66) | 0.239 | 0.166-0.344 | 0.000 | 0.874 | 0.539-1.418 | 0.587 |

| Curative resection | 67 (25.57) | 0.016 | 0.002-0.114 | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.004-0.227 | 0.001 |

Subsequent multivariate analysis illuminated that age > 75 years (HR = 2.276, 95%CI: 1.419-3.649, P = 0.001), CEA > 5 ng/mL (HR = 5.139, 95%CI: 3.093-8.539, P = 0.000), Primary LN involvement (HR = 1.828, 95%CI: 1.073-3.116, P = 0.027), multiple liver metastases (HR = 5.300, 95%CI: 1.627-17.262, P = 0.006), and extrahepatic metastases (HR = 6.187, 95%CI: 3.702-10.339, P = 0.0001) were high-risk factors. In contrast, MDT (HR = 0.608, 95%CI: 0.398-0.931, P = 0.022, Figure 1A) and curative resection (HR = 0.024, 95%CI: 0.003-0.177, P = 0.000) emerged as protective factors. During our analyses of 5-year OS rates, we found that despite the complexity of variables, MDT remained an independent protective factor (HR = 0.694, 95%CI: 0.515-0.937, P = 0.017, Table 5 and Figure 1B).

| n (%) | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Age > 75 | 61 (23.28) | 3.471 | 2.532-4.758 | 0.000 | 2.040 | 1.322-3.149 | 0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 133 (50.76) | 0.938 | 0.721-1.221 | 0.938 | |||

| BMI > 28 | 46 (17.56) | 0.951 | 0.679-1.331 | 0.769 | |||

| CEA > 5 ng/mL | 125 (47.71) | 2.446 | 1.872-3.195 | 0.000 | 2.516 | 1.847-3.428 | 0.000 |

| Colon primary | 118 (45.04) | 1.349 | 1.035-1.757 | 0.027 | 0.828 | 0.622-1.102 | 0.195 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 36 (13.74) | 0.792 | 0.529-1.184 | 0.256 | |||

| Poor differentiation | 37 (14.12) | 1.102 | 0.758-1.603 | 0.611 | |||

| Primary tumor category ≥ T3 | 202 (77.10) | 0.969 | 0.710-1.322 | 0.841 | |||

| Primary LN involvement | 178 (67.94) | 1.567 | 1.175-2.088 | 0.002 | 1.143 | 0.835-1.566 | 0.404 |

| Multiple liver metastases | 210 (80.15) | 3.852 | 2.592-5.725 | 0.000 | 2.563 | 1.671-3.932 | 0.000 |

| MDT | 93 (35.50) | 0.667 | 0.504-0.884 | 0.005 | 0.709 | 0.527-0.954 | 0.023 |

| Chemotherapy | 193 (73.66) | 0.203 | 0.147-0.281 | 0.000 | 0.591 | 0.388-0.900 | 0.014 |

| Curative resection | 67 (25.57) | 0.091 | 0.058-0.144 | 0.000 | 0.111 | 0.069-0.178 | 0.000 |

In MDT+ group, a significant majority of patients underwent a chest CT examination (100% vs 82.84%, P = 0.001). A SEER-based study including 46027 colorectal cancer patients found that about 20% of patients with colorectal liver metastasis were diagnosed with lung metastases simultaneously[16]. Furthermore, resection of liver and lung metastases brings better oncological outcomes than resection of liver metastases only[18]. Thus, the high frequency of chest CT examinations observed in the MDT+ group aligns with the need for comprehensive diagnostics in the management of patients with synchronous colorectal liver cancer. Moreover, the rate of abdomen MRI examination was significantly higher in MDT+ group compared to the MDT- group (P = 0.000), indicating a greater focus on identifying patients with questionable or curatively resectable liver metastases[19,20]. Most cancer therapy guidelines and clinical research underscore the importance of TNM staging in informing treatment strategies, reinforcing the value of accurate preoperative radiological TNM staging in treatment planning and monitoring clinical efficacy. Moreover, researchers have also proved that preoperative tumor staging increased cancer-specific endpoints[21]. Therefore, the increased likelihood of comprehensive baseline examination in patients under the MDT model can significantly contribute to more effective cancer treatment planning. For patients with synchronous liver metastases, PET-CT examination was frequently selected as the diagnostic modality of choice[22]. Notably, a substantial 80% of patients in the MDT+ group received chemotherapy (P = 0.019). A study from Phelip et al[23] indicated that a multidisciplinary meeting was the only factor independently associated with administration of chemotherapy.

Within the MDT+ group, patients were categorized into two subgroups: Those initially deemed resectable and those considered potentially resectable. Despite ongoing controversies surrounding the use of neo-adjuvant therapy for patients with initially resectable synchronous liver metastases[24-28], several benefits of neo-adjuvant therapy can be identified. Firstly, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy provides a “window period” that allows for the observation of any new unresectable liver metastases, thereby preventing unnecessary operations[29]. Secondly, neo-adjuvant therapy can potentially increase the chances of R0 surgery and the volume of residual liver post-surgery[30,31]. Thirdly, combining neo-adjuvant chemotherapy with adjuvant chemotherapy may enhance the outcomes of patients undergoing curative surgery[32,33]. Given these benefits, we often advocate for neo-adjuvant therapy, especially for patients with large liver metastases and large number of liver metastases or suspicious LN metastases. However, the status of the primary tumor lesion, patient willingness, chemotherapy toxicity and risk of disease progression should still be considered[26].

Successful conversion is an important goal for potentially resectable patients, while the symptoms and tumor burden usually influence the treatment strategy for unresectable patients. Large clinical trials have reported that the rates of successful conversion of unresectable liver metastases were about 4%-15%[34,35]. We observed a similar proportion (17.11% in MDT+ group and 9.46% in MDT- group) in our study. Research showed that the resection margin width of liver metastases was independently associated with OS rates[36]. However, complete radiological response only contributed 15%-70% of complete pathological response, and even among patients with a complete pathological response, long-term remission occurred in only 20%-50% of those treated with systemic therapy[37]. For patients who convert to be curatively resectable, we advocate for immediate curative resection, given the hepatotoxicity and potential for decreased chemosensitivity associated with prolonged chemotherapy. As the macroscopic disease disappears on preoperative imaging, an excision extension according to the baseline imaging data is recommended.

Despite the significantly higher 5-year OS rates of resectable colorectal liver metastasis (37%-49%) in contrast to unresectable liver metastases(2%-4%)[5,38,39], only about 10% of patients in our study were diagnosed as initially resectable. Given these stark contrasts, the pursuit of resectability remains crucial. We typically discourage palliative excision of liver metastases, yet for patients who lose the opportunity for curative resection due to primary tumor complications, we do advocate for the R0 resection of liver metastases[40]. Over 90% of patients underwent simultaneous combined laparoscopic resection in MDT+ group. Simultaneous liver and colorectal resections for metastatic colorectal cancer are associated with similar long-term cancer outcomes compared with staged procedures[41,42]. Considering factors such as operation duration, blood loss, hospital stay, and morbidity[43,44], patients can benefit much more from simultaneous operations. While long-term outcomes like overall survival, progression-free survival, and local recurrence after excision radio frequency ablation (RFA) remain contentious[45,46], we usually prefer excision unless specialists in our MDT meeting agree that excision is a great risk or complete ablation of liver metastases with RFA is possible. In our MDT, intraoperative RFA was performed by doctors from the department of intraoperative ultrasound. And only 5 of 30 patients in MDT+ group received RFA.

In the last part of this study, after adjusting for variables like age, primary LN involvement, multiple liver metastases, extrahepatic metastases, and curative resection, we discovered that MDT meetings were a protective factor for 1-year OS (HR = 0.608, 95%CI: 0.398-0.931, P = 0.022, Table 4) and 5-year OS (HR = 0.694, 95%CI: 0.515-0.937, P = 0.017, Table 5). Patients may achieve this via the improvement of patients’ treatment compliance, accurate radiological TNM staging, and an increased proportion of curative resection and systemic therapy in the MDT model.

The successful operation of a MDT necessitates fixed members, consistent meeting time, and location, an academic secretary with a medical background, and chat software enabling constant communication among team members. An MDT can help mitigate incomplete decisions made by individual doctors. Nonetheless, further evidence is still needed to confirm these benefits and assess the clinical benefits in light of the time and financial costs.

Multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) have been implemented in numerous large hospitals; however, critiques persist due to the high costs and limited strong evidence of their effectiveness.

The motivation behind this article is to provide further evidence on the application of MDTs in the field of colorectal liver metastasis. By conducting this research, we aim to contribute to the existing knowledge base and enhance the under

The objective of this study is to evaluate the effects of MDTs on patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases and provide insights and recommendations on the management of synchronous colorectal liver metastases.

This retrospective study investigated the influence of MDT involvement on clinical data of patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases at the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital.

The analysis revealed significant statistical increases in the rates of chest computed tomography examination (P = 0.001), abdomen magnetic resonance imaging examination (P = 0.000), and preoperative image staging (P = 0.0000) among patients in the MDT+ group. Furthermore, a higher proportion of patients in the MDT+ group received chemotherapy (P = 0.019) and underwent curative resection (P = 0.042). Multivariable analysis demonstrated that patients assessed through MDT meetings had higher 1-year overall survival [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.608, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.398-0.931, P = 0.022] and 5-year overall survival (HR = 0.694, 95%CI: 0.515-0.937, P = 0.017).

The findings of this study provide evidence that MDT management offers patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases increased access to comprehensive examinations and treatments, ultimately leading to improved outcomes.

This study conducted from the perspective of surgeons through a retrospective analysis of clinical records, observed that MDT management offers increased opportunities for comprehensive examinations and treatments in patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases, consequently leading to improved treatment outcomes. This further validates the benefits of MDT management.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: Chairman, Colorectal Anal Surgery Professional Committee, Chinese Research Hospital Society; Member of Colorectal Surgery Group, Surgery Society of Chinese Medical Association; Standing member of the General Surgery Committee of the PLA.

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Billeter A, Germany; Tanabe M, Japan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 63874] [Article Influence: 15968.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (174)] |

| 2. | McMillan DC, McArdle CS. Epidemiology of colorectal liver metastases. Surg Oncol. 2007;16:3-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C, Coatmeur O, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2006;244:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 1005] [Article Influence: 52.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Giannis D, Sideris G, Kakos CD, Katsaros I, Ziogas IA. The role of liver transplantation for colorectal liver metastases: A systematic review and pooled analysis. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2020;34:100570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stewart CL, Warner S, Ito K, Raoof M, Wu GX, Kessler J, Kim JY, Fong Y. Cytoreduction for colorectal metastases: liver, lung, peritoneum, lymph nodes, bone, brain. When does it palliate, prolong survival, and potentially cure? Curr Probl Surg. 2018;55:330-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Grass C, Umansky R. Problems in promoting the growth of multi-disciplinary diagnostic and counseling clinics for mentally retarded children in nonmetropolitan areas. Am J Public Health. 1971;61:698-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kurpad R, Kim W, Rathmell WK, Godley P, Whang Y, Fielding J, Smith L, Pettiford A, Schultz H, Nielsen M, Wallen EM, Pruthi RS. A multidisciplinary approach to the management of urologic malignancies: does it influence diagnostic and treatment decisions? Urol Oncol. 2011;29:378-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Taylor C, Munro AJ, Glynne-Jones R, Griffith C, Trevatt P, Richards M, Ramirez AJ. Multidisciplinary team working in cancer: what is the evidence? BMJ. 2010;340:c951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thornton S. Time to review utility of multidisciplinary team meetings. BMJ. 2015;351:h5295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chinai N, Bintcliffe F, Armstrong EM, Teape J, Jones BM, Hosie KB. Does every patient need to be discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting? Clin Radiol. 2013;68:780-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pillay B, Wootten AC, Crowe H, Corcoran N, Tran B, Bowden P, Crowe J, Costello AJ. The impact of multidisciplinary team meetings on patient assessment, management and outcomes in oncology settings: A systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;42:56-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | MacDermid E, Hooton G, MacDonald M, McKay G, Grose D, Mohammed N, Porteous C. Improving patient survival with the colorectal cancer multi-disciplinary team. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:291-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ye YJ, Shen ZL, Sun XT, Wang ZF, Shen DH, Liu HJ, Zhang WL, Chen YL, Zhou J, Poston GJ, Wang S. Impact of multidisciplinary team working on the management of colorectal cancer. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012;125:172-177. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Gobbi PG, Rossi S, Comelli M, Ravetta V, Rosa LL, Brugnatelli S, Corbella F, Delfanti S, Abumalouh I, Dionigi P. The Prognosis of Patients with Liver Metastases from Colorectal Cancer still Depends on Anatomical Presentation more than on Treatments. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2015;15:511-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schmidt T, Strowitzki MJ, Reissfelder C, Rahbari NN, Nienhueser H, Bruckner T, Rahäuser C, Keppler U, Schneider M, Büchler MW, Ulrich A. Influence of age on resection of colorectal liver metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:729-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Qiu M, Hu J, Yang D, Cosgrove DP, Xu R. Pattern of distant metastases in colorectal cancer: a SEER based study. Oncotarget. 2015;6:38658-38666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lan YT, Jiang JK, Chang SC, Yang SH, Lin CC, Lin HH, Wang HS, Chen WS, Lin TC, Lin JK. Improved outcomes of colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases in the era of the multidisciplinary teams. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:403-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Andres A, Mentha G, Adam R, Gerstel E, Skipenko OG, Barroso E, Lopez-Ben S, Hubert C, Majno PE, Toso C. Surgical management of patients with colorectal cancer and simultaneous liver and lung metastases. Br J Surg. 2015;102:691-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bipat S, van Leeuwen MS, Ijzermans JN, Comans EF, Planting AS, Bossuyt PM, Greve JW, Stoker J. Evidence-base guideline on management of colorectal liver metastases in the Netherlands. Neth J Med. 2007;65:5-14. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Zech CJ, Korpraphong P, Huppertz A, Denecke T, Kim MJ, Tanomkiat W, Jonas E, Ba-Ssalamah A; VALUE study group. Randomized multicentre trial of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI versus conventional MRI or CT in the staging of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2014;101:613-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Palmer G, Martling A, Cedermark B, Holm T. Preoperative tumour staging with multidisciplinary team assessment improves the outcome in locally advanced primary rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1361-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Moulton CA, Gu CS, Law CH, Tandan VR, Hart R, Quan D, Fairfull Smith RJ, Jalink DW, Husien M, Serrano PE, Hendler AL, Haider MA, Ruo L, Gulenchyn KY, Finch T, Julian JA, Levine MN, Gallinger S. Effect of PET before liver resection on surgical management for colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1863-1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Phelip JM, Molinié F, Delafosse P, Launoy G, Trétarre B, Bara S, Buémi A, Velten M, Danzon A, Ganry O, Bouvier AM, Grosclaude P, Faivre J. A population-based study of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage-II and -III colon cancers. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:144-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Adam R, de Gramont A, Figueras J, Kokudo N, Kunstlinger F, Loyer E, Poston G, Rougier P, Rubbia-Brandt L, Sobrero A, Teh C, Tejpar S, Van Cutsem E, Vauthey JN, Påhlman L; of the EGOSLIM (Expert Group on OncoSurgery management of LIver Metastases) group. Managing synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:729-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 39.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Gruenberger T, Beets G, Van Laethem JL, Rougier P, Cervantes A, Douillard JY, Figueras J, Gruenberger B, Haller DG, Labianca R, Maleux G, Roth A, Ducreux M, Schmiegel W, Seufferlein T, Van Cutsem E. Treatment sequence of synchronously (liver) metastasized colon cancer. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:1119-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhu C, Ren X, Liu D, Zhang C. Oxaliplatin-induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. Toxicology. 2021;460:152882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tepelenis K, Pappas-Gogos G, Ntellas P, Tsimogiannis K, Dadouli K, Mauri D, Glantzounis GK. The Role of Preoperative Chemotherapy in the Management of Synchronous Resectable Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Meta-Analysis. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:4499-4511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bonney GK, Coldham C, Adam R, Kaiser G, Barroso E, Capussotti L, Laurent C, Verhoef C, Nuzzo G, Elias D, Lapointe R, Hubert C, Lopez-Ben S, Krawczyk M, Mirza DF; LiverMetSurvey International Registry Working Group. Role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable synchronous colorectal liver metastasis; An international multi-center data analysis using LiverMetSurvey. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:716-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cleary JM, Tanabe KT, Lauwers GY, Zhu AX. Hepatic toxicities associated with the use of preoperative systemic therapy in patients with metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma to the liver. Oncologist. 2009;14:1095-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tanaka K, Adam R, Shimada H, Azoulay D, Lévi F, Bismuth H. Role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of multiple colorectal metastases to the liver. Br J Surg. 2003;90:963-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Leonard GD, Brenner B, Kemeny NE. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy before liver resection for patients with unresectable liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2038-2048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mentha G, Majno P, Terraz S, Rubbia-Brandt L, Gervaz P, Andres A, Allal AS, Morel P, Roth AD. Treatment strategies for the management of advanced colorectal liver metastases detected synchronously with the primary tumour. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33 Suppl 2:S76-S83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, Poston GJ, Schlag PM, Rougier P, Bechstein WO, Primrose JN, Walpole ET, Finch-Jones M, Jaeck D, Mirza D, Parks RW, Collette L, Praet M, Bethe U, Van Cutsem E, Scheithauer W, Gruenberger T; EORTC Gastro-Intestinal Tract Cancer Group; Cancer Research UK; Arbeitsgruppe Lebermetastasen und-tumoren in der Chirurgischen Arbeitsgemeinschaft Onkologie (ALM-CAO); Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG); Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD). Perioperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX4 and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC Intergroup trial 40983): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1007-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1478] [Cited by in RCA: 1434] [Article Influence: 84.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Falcone A, Ricci S, Brunetti I, Pfanner E, Allegrini G, Barbara C, Crinò L, Benedetti G, Evangelista W, Fanchini L, Cortesi E, Picone V, Vitello S, Chiara S, Granetto C, Porcile G, Fioretto L, Orlandini C, Andreuccetti M, Masi G; Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest. Phase III trial of infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan (FOLFOXIRI) compared with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: the Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1670-1676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 830] [Cited by in RCA: 887] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Souglakos J, Androulakis N, Syrigos K, Polyzos A, Ziras N, Athanasiadis A, Kakolyris S, Tsousis S, Kouroussis Ch, Vamvakas L, Kalykaki A, Samonis G, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V. FOLFOXIRI (folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin and irinotecan) vs FOLFIRI (folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan) as first-line treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer (MCC): a multicentre randomised phase III trial from the Hellenic Oncology Research Group (HORG). Br J Cancer. 2006;94:798-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sadot E, Groot Koerkamp B, Leal JN, Shia J, Gonen M, Allen PJ, DeMatteo RP, Kingham TP, Kemeny N, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR, DʼAngelica MI. Resection margin and survival in 2368 patients undergoing hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: surgical technique or biologic surrogate? Ann Surg. 2015;262:476-85; discussion 483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bischof DA, Clary BM, Maithel SK, Pawlik TM. Surgical management of disappearing colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1414-1420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Valdimarsson VT, Syk I, Lindell G, Sandström P, Isaksson B, Rizell M, Norén A, Ardnor B, Sturesson C. Outcomes of Simultaneous Resections and Classical Strategy for Synchronous Colorectal Liver Metastases in Sweden: A Nationwide Study with Special Reference to Major Liver Resections. World J Surg. 2020;44:2409-2417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lordan JT, Karanjia ND, Quiney N, Fawcett WJ, Worthington TR. A 10-year study of outcome following hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases - The effect of evaluation in a multidisciplinary team setting. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:302-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hwang M, Jayakrishnan TT, Green DE, George B, Thomas JP, Groeschl RT, Erickson B, Pappas SG, Gamblin TC, Turaga KK. Systematic review of outcomes of patients undergoing resection for colorectal liver metastases in the setting of extra hepatic disease. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1747-1757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Lykoudis PM, O'Reilly D, Nastos K, Fusai G. Systematic review of surgical management of synchronous colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2014;101:605-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wang LJ, Wang HW, Jin KM, Li J, Xing BC. Comparison of sequential, delayed and simultaneous resection strategies for synchronous colorectal liver metastases. BMC Surg. 2020;20:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gavriilidis P, Sutcliffe RP, Hodson J, Marudanayagam R, Isaac J, Azoulay D, Roberts KJ. Simultaneous versus delayed hepatectomy for synchronous colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2018;20:11-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Tian ZQ, Su XF, Lin ZY, Wu MC, Wei LX, He J. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open liver resection for colorectal liver metastases. Oncotarget. 2016;7:84544-84555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lee WS, Yun SH, Chun HK, Lee WY, Kim SJ, Choi SH, Heo JS, Joh JW, Choi D, Kim SH, Rhim H, Lim HK. Clinical outcomes of hepatic resection and radiofrequency ablation in patients with solitary colorectal liver metastasis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:945-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ko S, Jo H, Yun S, Park E, Kim S, Seo HI. Comparative analysis of radiofrequency ablation and resection for resectable colorectal liver metastases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:525-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |