Published online Aug 15, 2023. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v15.i8.1349

Peer-review started: January 14, 2023

First decision: March 14, 2023

Revised: March 29, 2023

Accepted: June 25, 2023

Article in press: June 25, 2023

Published online: August 15, 2023

Processing time: 207 Days and 18.8 Hours

There is an intimate crosstalk between cancer formation, dissemination, treatment response and the host immune system, with inducing tumour cell death the ultimate therapeutic goal for most anti-cancer treatments. However, inducing a purposeful synergistic response between conventional therapies and the immune system remains evasive. The release of damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) is indicative of immunogenic cell death and propagation of established immune responses. However, there is a gap in the literature regarding the impor

To investigate the effects of conventional therapies on DAMP expression and to determine whether OAC is an immunogenic cancer.

We investigated the levels of immunogenic cell death-associated DAMPs, calreticulin (CRT) and HMGB1 using an OAC isogenic model of radioresistance. DAMP expression was also assessed directly using ex vivo cancer patient T cells (n = 10) and within tumour biopsies (n = 9) both pre and post-treatment with clinically relevant chemo(radio)therapeutics.

Hypoxia in combination with nutrient deprivation significantly reduces DAMP expression by OAC cells in vitro. Significantly increased frequencies of T cell DAMP expression in OAC patients were observed following chemo

In conclusion, OAC expresses an immunogenic phenotype with two distinct subgroups of high and low DAMP expressors, which correlated with tumour regression grade and lymphatic invasion. It also identifies DAMPs namely CRT and HMGB1 as potential promising biomarkers in predicting good pathological responses to conventional chemo(radio)therapies currently used in the multimodal management of locally advanced disease.

Core Tip: The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of conventional therapies on damage associated molecular patterns expression and we determined oesophageal adenocarcinoma is an immunogenic cancer and is a viable target for immunotherapeutics.

- Citation: Donlon NE, Davern M, Sheppard A, O'Connell F, Moran B, Nugent TS, Heeran A, Phelan JJ, Bhardwaj A, Butler C, Ravi N, Donohoe CL, Lynam-Lennon N, Maher S, Reynolds JV, Lysaght J. Potential of damage associated molecular patterns in synergising radiation and the immune response in oesophageal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2023; 15(8): 1349-1365

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v15/i8/1349.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v15.i8.1349

The fundamental purpose of radiotherapy is the induction of maximal local tumour cell death and the abrogation of clonogenic survival, with minimally killing of normal cells[1]. In contemporaneous terms, radiotherapy remains a pillar of cancer treatment in the curative and neoadjuvant setting for oesophageal cancer[2] and moreover it has become appa

One of the most promising effects of radiotherapy is immunologic cell death and the release damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are able to activate immune cells and other cells within the tumour microenvironment (TME), which can then induce suppression or promotion of tumour growth[6]. One of the essential effects of DAMPs is the activation of dendritic cells (DC’s). The exposure of DCs to some DAMPs leads to maturation of primed DCs, leading to their activation and successful presentation of antigens to CD8+ T cells[7]. The activation of CD8+ T cells, known as cytotoxic T lymphocytes can directly kill tumour cells, trigger the recruitment of additional anti-tumour cells, release anti-cancer cytokines and inhibit tumour growth[8]. Calreticulin, one of the most studied DAMPs and is an endoplasmic reticulum resident protein with different roles including chaperone activity and maintenance of Ca2+ homeostasis and functionally regulates protein synthesis, cell proliferation, adhesion, invasion and nuclear transport[9,10].

High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is another well-known DAMP molecule and binds to toll-like receptor 4 on DCs, promoting antigen cross-presentation on the surface of T cells[11]. Enhanced release of HMGB1 and increased calreticulin expression are important for priming antigen-specific T-cell responses, thereby promoting synergistic effect between radiation and immunotherapy[12]. However the expression of DAMPs including HMGB1 and CRT by T cells themselves has not been studied to date, to the best of the author’s knowledge. T cell DAMP expression could be indicative of T cell exhaustion, suppression or death within the hostile tumour microenvironment but this could also lead to the activation of other immune cells within the tumour. The ultimate outcome of T cell DAMP expression post chemotherapy or radiotherapy is an area that requires further study.

The role of the TME in cancer progression is evolving and garnering increased interest in the field where anti-tumour functions are downregulated, fundamentally in response to tumour-derived signals[13]. Simultaneously, immune cells in the tumour microenvironment fail to exercise anti-tumour effector functions, and are often co-opted to promote tumour growth[14]. The TME consists of an abundance of cancer cells of different metabolic phenotypes, reflecting fluctuating nutrient availability, to ensure their viability and propagation[15]. Indeed, hypoxia is a common feature of tumour development and progression of solid tumours, and is largely due to the rapid growth of tumour cells. Therefore, cancer and stromal cells often have restricted access to nutrients and oxygen[16]. Most solid tumours have regions either permanently or transiently subjected to hypoxia because of dysregulated vascularisation and inconsistent supply[17]. Often, hypoxia leads to immune and stromal cell dysregulation in a way that supports cancer growth: fibroblasts can be transformed into tumour-prone cancer-associated fibroblasts, ECM remodelling supports metastases, vascularisation process facilitates cancer progression, and anti-tumour immune function becomes generally suppressed[13]. Glucose and glutamine are central metabolites for catabolic and anabolic metabolism, which is under investigation for diagnostic methodology and therapeutic potentials to overcome the often prevailing precarious immunosuppressive microenvironment[18]. In the same vein, hypoxia may institute a number of events in the tumour microenvironment that can lead to the expansion and propagation of aggressive clones from heterogeneous tumour cells and thereby promote a lethal phenotype[19]. It must also be borne in mind tumour antigens need to be made accessible to the immune system, and the presence of adjuvants facilitating the recruitment, differentiation, and activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the microenvironment is essential for the successful priming of anti-tumour immunity[20]. To this end, the orchestration of immunogenic forms of tumour cell death are known to release DAMPs, including calreticulin and HMGB1, promoting the recruitment and maturation of APCs[21]. The mode of cell death resulting from ionizing irradiation is not congruent and is dependent on the irradiation dose, the fractionation regimen, and the genetic repertoire of the irradiated cells, many of which remain yet to be elucidated[22]. A number of studies have examined the initial steps of anti-tumour immune priming by fractionated and bolus radiation delivery (20 Gy, 4 Gy × 2 Gy, 2 Gy, 0 Gy) with cell lines of triple-negative breast cancer in vitro and in vivo[20].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of fractionated and bolus dosing regimen radiotherapy and conditions of the tumour microenvironment on DAMP expression both in vitro using radiosensitive and radioresistant oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC) cells and to also investigate the impact of conventional treatment modalities on DAMP expression using ex vivo OAC patient blood and tumours both pre and post-treatment by immune and non-immune cells. Finally, we endeavoured to draw meaningful clinical correlations with DAMP expression on patient samples.

Ethical approval was granted from the Beacon and Tallaght/St James’s Hospital Ethics Committees. Informed written consent was obtained for all sample and data collection, which was carried out using best clinical practice guidelines. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Patient samples were pseudonymised to protect privacy.

All patients who consented to fresh specimen collection were enrolled between 2018-2021. Tumour biopsies were obtained from oesophageal adenocarcinoma patients prior to treatment at St James’s Hospital, Dublin. A total of 9 biopsies and 10 whole blood samples were used for analysis with all patient samples being treatment naïve prior to having neoadjuvant therapies to ensure clinical relevance of the study population. All patients had locally advanced disease and were T2/3Nany.

Biopsies were enzymatically digested to perform OAC cell phenotyping. Briefly, tissue was minced using a scalpel and digested in collagenase solution [2 mg/mL of collagenase type IV (sigma) in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (GE healthcare) supplemented with 4% (v/v) foetal bovine serum] at 37 °C and 1500 rpm on an orbital shaker. Tissue was filtered and washed with FACs buffer (PBS containing 1% foetal bovine serum and 0.01% sodium azide). Cells were then stained for flow cytometry.

Human OAC cell lines OE33 were purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures, established from a poorly differentiated stage IIA adenocarcinoma of the lower oesophagus of a 73-year old female patient. An in-house isogenic radioresistant model was generated[23]. Parental (OE33P) and radioresistant (OE33R) cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (Gibco) and supplemented with 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin (50 U/mL penicillin 100 μg/mL streptomycin) and 10% (v/v) foetal bovine serum (Gibco) and maintained in a humidified chamber at 37 °C 5% CO2. Cell lines were tested regularly to ensure mycoplasma negativity.

In a separate set of experiments OE33 cells were cultured in complete RPMI (cRPMI, 10% FBS, 1% P/S), glucose-free RPMI [Gibco (11560406), 10% FBS, 1% P/S], glutamine-free and serum deprived RPMI (Gibco, 10% FBS, 1% P/S) under normoxic conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2, 21% atmospheric O2) or hypoxic conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2, 0.5% O2) for 48 h using the H35 Don Whitley hypoxia station (Don Whitley Scientific).

Cell lines were irradiated using the X-Ray generator RS225 system (Gulman Medical, United Kingdom). The instrument was upper-heated for 45 min prior to irradiation and irradiated with bolus dosing of 2 Gy, 10 Gy, 20 Gy, fractionated dosing 3 Gy × 2 Gy, 3 Gy × 4 Gy, 3 Gy × 8 Gy, or mock irradiated (cells were placed into the irradiator but not irradiated). For irradiation of the hypoxic plates, these were placed in mini hypoxia chambers and transferred to the irradiator and subsequently transferred back after receiving the appropriate dose of radiation.

OE33 cells were trypsinised and stained with zombie aqua viability (Biolegend, United States) dye. Antibodies used for OAC cell lines included: Calreticulin-FITC and HMGB1-PE. OE33P and OE33R cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde solution and acquired using BD FACs CANTO II (BD Biosciences) using Diva software and analysed using FlowJo v10 software (TreeStar Inc.).

Tumour tissue biopsies were stained with zombie aqua viability dye (Biolegend, United States) as per manufacturer’s recommendations and the following cell surface antibodies: HMGB1-PE, CD8-BV421 (BD Biosciences, United States), calreticulin-FITC, CD3-APC (Miltenyi, United States) and CD4-PerCpCy5.5 (eBiosciences, United States). Cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde solution (Santa Cruz, United States), washed and resuspended in FACs buffer and acquired using BD FACs CANTO II (BD Biosciences) using Diva software version 10 and analysed using FlowJo v10 software (TreeStar Inc.).

Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA, United States) software and was expressed as mean values ± SEM. Statistical differences between two treatments in a particular cell line were analysed using a paired parametric t-test. To compare the statistical differences between two different cell lines an unpaired parametric t-test was conducted. To compare differences between paired treatments of patient samples, Wilcoxon signed rank test was conducted. Statistical significance was determined as P ≤ 0.05.

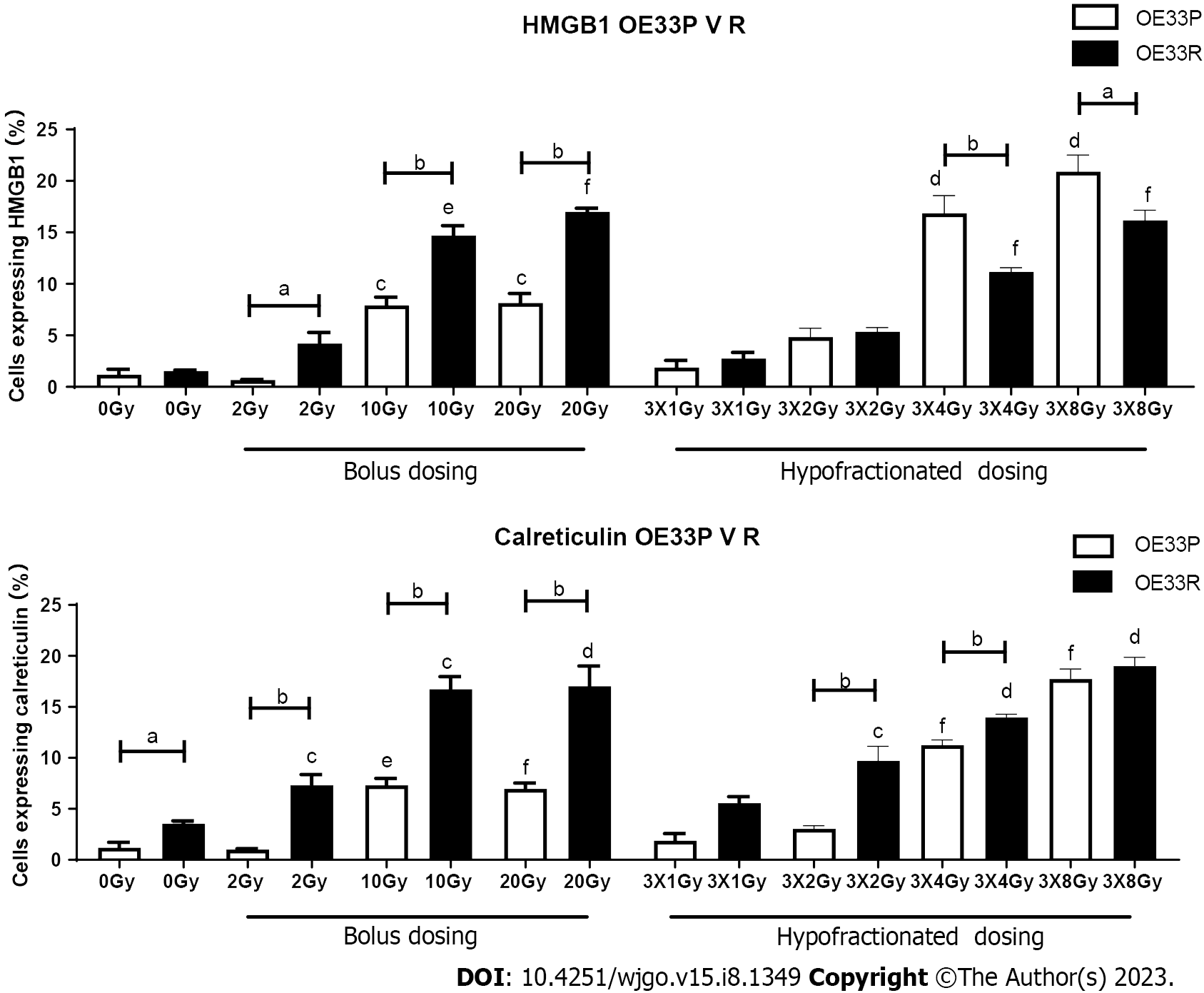

In order to ascertain basal DAMP expression levels on a radiosensitive (OE33P) and a radioresistant (OE33R) oesophageal adenocarcinoma as well as the effects of different doses of radiation, cells were stained with antibodies for the DAMPs HMGB1 and calreticulin and assessed by flow cytometry.

In the OE33P cell line, there was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 10 Gy (7.93+/-0.79), 20 Gy (8.16+/

In the OE33P cell line, there was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin by 10 Gy (7.33+/-0.66), 20 Gy (6.96+/

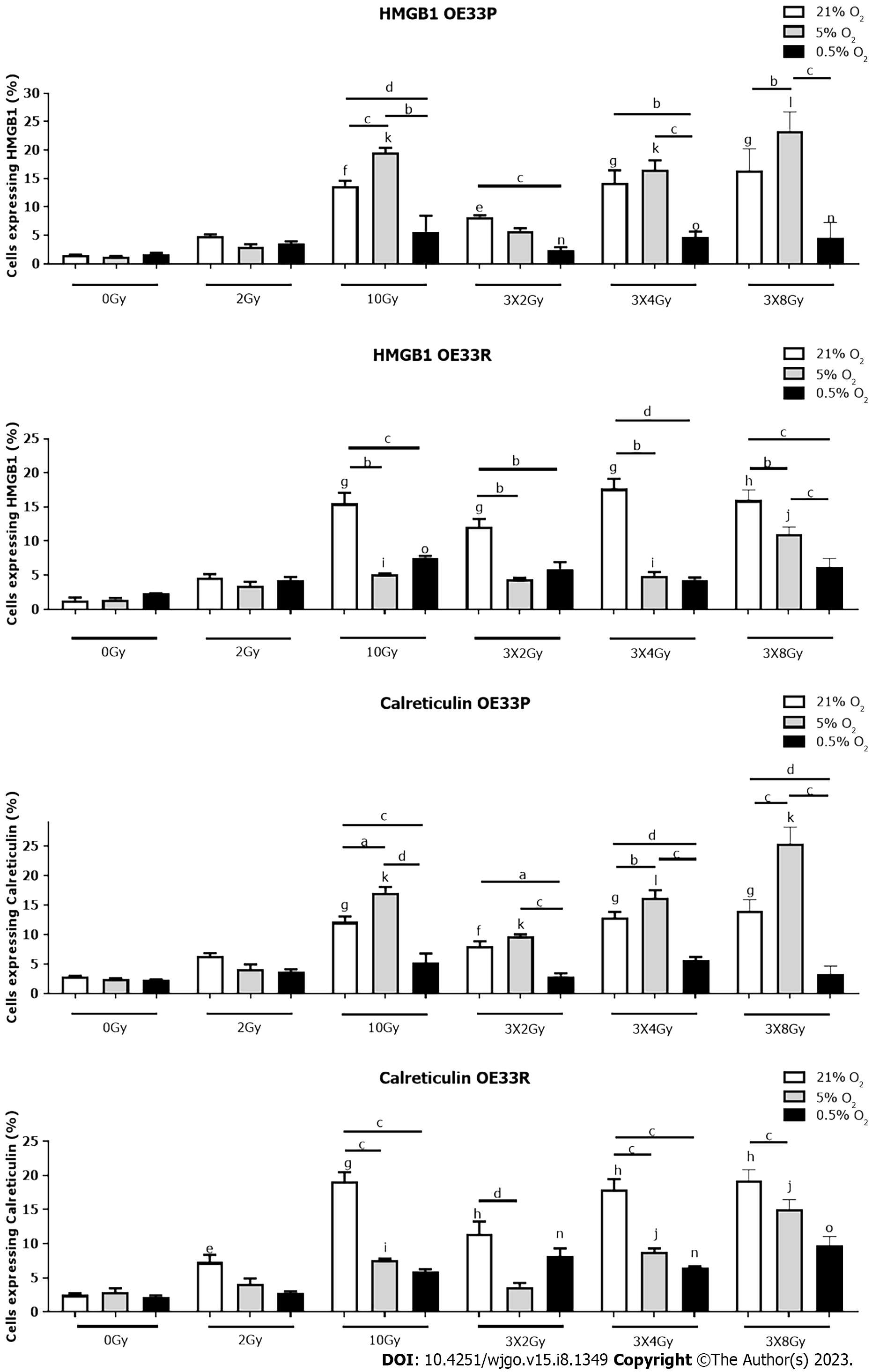

The development of a hypoxic milieu is as a consequence of the imbalance triggered by increased oxygen consumption by rapidly proliferating tumour cells and propagated by tumour angiogenesis. The overall impact is to diminish immune function and the focus of these experiments is to determine the effect on DAMP expression in the presence of differing levels of hypoxia.

In the radiosensitive OE33P cell line there was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy normoxia (13.73 ± 0.86), 3 Gy × 2 Gy normoxia (8.26+/-0.28), 3 Gy × 4 Gy normoxia (14.23 ± 2.2), 3 Gy × 8Gy normoxia (16.4 ± 2.2) compared to 0 Gy normoxia (1.51 ± 0.12) P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.001, P < 0.001 respectively. There was also a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 10 Gy 5% O2 (19.6 ± 0.82), 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 (16.6 ± 1.59), 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 (23.2 ± 1.97) compared to 0 Gy 5% O2 (1.33 ± 0.05) P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001. There is a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 2 Gy 0.5% O2 (2.36 ± 0.55), 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% O2 (4.68 ± 1.01) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 (4.65 ± 1.52) compared to 0 Gy 0.5% O2 (1.67 ± 0.26) P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.01 respectively. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 10 Gy 5% O2 (19.6 ± 0.82) compared to 10 Gy normoxia (13.73 ± 0.86) P < 0.001 and 10 Gy 0.5% O2 (5.64 ± 2.83) P < 0.001. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 2 Gy normoxia (8.26 ± 0.28) compared to 3 Gy × 2 Gy 0.5% O2 (2.36 ± 0.55) P < 0.001. There was also a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 4 Gy normoxia (14.23 ± 2.2) and 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 (16.6 ± 1.59) compared to 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% O2 (4.68 ± 1) P < 0.01, P < 0.001 respectively. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 (23.3 ± 1.97) compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy normoxia (16.4 ± 2.2) P < 0.01 and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 (4.65 ± 1.52) P < 0.001 (Figure 2).

In the OE33R cell line, there was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy (15.53 ± 1.55), 3 Gy × 2 Gy (12.07 ± 1.17), 3 Gy × 4 Gy (17.7 ± 1.42) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy (16 ± 0.86) compared to 0 Gy normoxia (1.32 ± 0.43) P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001 respectively. There is a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy 5% O2 (5.11 ± 0.44), 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 (4.92 ± 0.55) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 (11 ± 0.61) compared to 0 Gy 5% O2 (1.45 ± 0.2) P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.01 respectively. There was also a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 10 Gy 0.5% O2 (7.59 ± 0.24) compared to 0 Gy 0.5% O2 (2.32 ± 0.3) P < 0.01. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy normoxia (15.53 ± 1.55) compared to 10 Gy 5% O2 (5.11 ± 0.14) P < 0.01 and 10 Gy 0.5% O2 (7.59 ± 0.24) P < 0.001. There was also a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 2 Gy normoxia (12.07 ± 1.17) compared to 3 Gy × 2 Gy 5% O2 (4.42 ± 0.19) P < 0.01 and 3 Gy × 2 Gy 0.5% O2 (5.91 ± 1.02) P < 0.01. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 4 Gy normoxia (17.7 ± 1.42) compared to 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 (4.92 ± 0.55) P < 0.001 and 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% O2 (4.35 ± 0.31) P < 0.001. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 8 Gy normoxia (16 ± 0.86) compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 (11 ± 0.61) P < 0.001 and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 (6.24 ± 0.69) P < 0.001 (Figure 2).

In the OE33P cell line, there was a significant increase in expression of calreticulin in response to 10 Gy irradiation (12.13 ± 0.92), fractionated dosing 3 Gy × 2 Gy (8.05 ± 0.81), 3 Gy × 4 Gy (12.86 ± 0.98) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy (14 ± 1.11) compared to non-irradiated cells (2.34 ± 0.87) P < 0.001, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.001 respectively. There was a significant increase in expression of calreticulin with 10 Gy at 5% O2 (5.21 ± 1.58), 3 Gy × 2 Gy at 5% O2 (9.73 ± 0.29), 3 Gy × 4 Gy at 5%O2 (16.23 ± 1.27), 3 Gy × 8 Gy at 5% O2 (25.47 ± 1.61) compared to 0 Gy 5% O2 (2.49 ± 0.11) P < 0.001, P < 0.01, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 respectively. There was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin in response to 10 Gy 5% O2 (17.13 ± 0.93) compared to 10 Gy (12.13 ± 0.93) with normal oxygen concentrations P < 0.05, and 10 Gy 0.5% O2 (5.21 ± 1.58) P<0.001 and 10 Gy 5% O2 compared to 10 Gy 0.5% O2P < 0.001. There was a significantly increased expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 2 Gy under normal oxygenation (8.05 ± 0.81) compared to 3 Gy × 2 Gy 5% O2 (9.72 ± 0.29) P < 0.001) and 3 Gy × 2 Gy 5% O2 compared to 3 Gy × 2 Gy 0.5% O2 (2.94 ± 0.48) P < 0.001. There was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 4 Gy normoxia (12.86 ± 0.98) compared to 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 (16.23 ± 1.27) P < 0.01 and 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% O2 (5.67 ± 0.52) P < 0.001 and a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 compared to 0.5% O2P < 0.001. There was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 8 Gy normal oxygenation (14 ± 1.11) compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 (25.47 ± 1.61) P < 0.001, 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 compared to 0.5% O2 (3.28 ± 0.77) P < 0.001, and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2P < 0.001 (Figure 2).

In the OE33 R cell line there was a significant increase in expression of calreticulin in response to 2 Gy irradiation (7.32 ± 1.03), 10 Gy irradiation (19.13 ± 2.32), fractionated dosing 3 Gy × 2 Gy (11.44 ± 1.82), 3 Gy × 4 Gy (17.9 ± 1.55) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy (19.23 ± 0.93) compared to non-irradiated cells (0 Gy) (2.3 ± 0.25) P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001 respectively. There was a significant increase in expression of calreticulin in response to 10 Gy at 5% O2 (7.59 ± 0.24), 3 Gy × 4 Gy at 5% O2 (8.8 ± 0.52), 3 Gy × 8 Gy at 5% O2 compared to 0 Gy 5% O2 (2.95 ± 0.54) P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.01 respectively. There was a significant increase in expression of calreticulin with 3 Gy × 2 Gy at 0.5% O2 (8.2 ± 1.13), 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% O2 (6.55 ± 0.14) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 (9.71 ± 0.78) compared to 0 Gy 0.5% O2 (2.15 ± 0.27) P < 0.01, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 respectively. There was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin in response to 10Gy with normal oxygen concentrations (19.13 ± 2.32) compared to 10 Gy 5% O2 (7.59 ± 0.24) P < 0.001, and 10 Gy 0.5% O2 (5.9 ± 0.36) P < 0.001. There was a significantly increased expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 2 Gy under normal oxygenation (11.44 ± 1.82) compared to 3 Gy × 2 Gy 5% O2 (3.68 ± 0.59) P < 0.001). There was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 4 Gy normoxia (17.9 ± 1.55) compared to 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 (8.8 ± 0.52) P < 0.001 and 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% O2 (6.55 ± 0.14) P < 0.001. There was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin in response to 3 Gy × 8 Gy normal oxygenation (19.23 ± 0.93) compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 (15.1 ± 0.78) P < 0.001 (Figure 2).

In summary, severe hypoxia in combination with higher bolus doses of radiation or hypofractionated doses reduces the expression of DAMPs on OAC cells irrespective of radiosenstivity. This likely reflects the reduced immune surveillance and activation which occurs under severe hypoxia. Treatments combining radiation with immunotherapy would need to address the hypoxic tumour microenvironment in order to optimise responses rates.

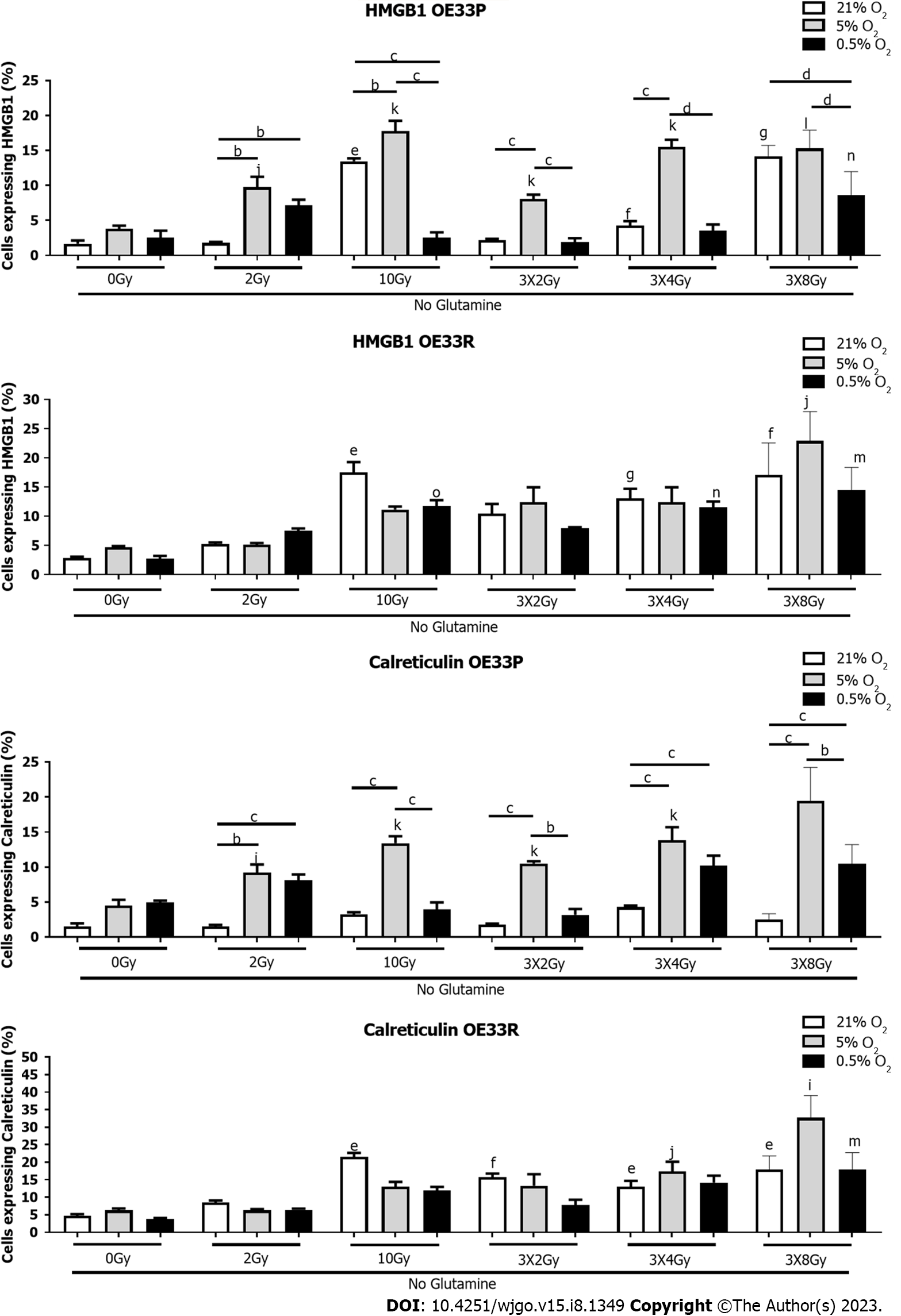

Both glutamine and glucose are essential for T cell activation and are essential for their differentiation, proliferation, and overall function. Cancer cells induce a highly metabolic state and preferentially utilise all nutrients available therefore limiting any potential nutrient supply to cells involved in anti-tumour immunity, propagating a pro-tumourigenic milieu. Here we look at both these important elements of the TME in isolation.

In the OE33P cell line, there was a significantly increased expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy normoxia no glucose (12.23 ± 0.27), 3 Gy × 2 Gy (13.33 ± 1.11), 3 Gy × 4 Gy (15.17 ± 1.52) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy (13.44 ± 2.18) compared to 0 Gy normoxia no glucose (4.95 ± 1.25) P < 0.05, P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001 respectively. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy 5% O2 no glucose (22.4 ± 2.94), 3 Gy × 2 Gy 5% O2 no glucose (10.28 ± 1.53), 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 no glucose (18.7 ± 1.6) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 no glucose (14.97 ± 2.28) P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.01 respectively. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy 5% O2 no glucose (22.4 ± 2.94) compared to 10 Gy normoxia no glucose (12.23 ± 0.27) P < 0.01 and 10 Gy 0.5% O2 no glucose (2.86 ± 0.41) P < 0.001. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 2 Gy normoxia no glucose (13.33 ± 1.11) compared to 3 Gy × 2 Gy 0.5% O2 no glucose (4.95 ± 0.47) P < 0.01. There was a significantly lower expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 no glucose (2.81 ± 0.95) compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy normoxia no glucose (13.44 ± 2.18) P < 0.001 and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 no glucose (14.97 ± 2.28) P < 0.01 (Figure 3).

In the OE33R cell line there was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy normoxia no glucose (22.17 ± 2.31), 3 Gy × 2 Gy (13.33 ± 1.11), 3 Gy × 4 Gy (23.8 ± 2.71) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy (41.53 ± 3.28) compared to 0 Gy normoxia no glucose (2.83 ± 0.71) P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, P < 0.001 respectively. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 10 Gy normoxia no glucose (22.17 ± 2.31) compared to 10 Gy 5% O2 no glucose (10.77 ± 0.78) P < 0.001, and 10 Gy 0.5% O2 no glucose (6.03 ± 0.59) P < 0.001. Additionally, there was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy 5% O2 no glucose (10.77 ± 0.78) compared to 10 Gy 0.5% O2 no glucose (6.03 ± 0.59) P < 0.01. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 2 Gy normoxia no glucose (13.33 ± 1.11) compared to 3 Gy × 2 Gy 5% O2 no glucose (8.08 ± 0.74) P < 0.01. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 8 Gy normoxia no glucose (41.53 ± 3.28) compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 no glucose (15.1 ± 3.25) P < 0.001 and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 no glucose (11.56 ± 1.93) P < 0.0001 (Figure 3).

In the OE33P cell line there was a significant increase in expression of calreticulin in response to 10 Gy at 5% O2 (14.07 ± 1.33), 3 Gy × 2 Gy at 5% O2 (11.68 ± 1.54), 3 Gy × 4 Gy at 5% O2 (15.7 ± 1.33), 3 Gy × 8 Gy at 5% O2 (14.77 ± 1.39) compared to 0 Gy 5% O2 (6.55 ± 0.99) P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 respectively. There was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin in response to 2 Gy 5% O2 (8.82 ± 0.95) compared to 2 Gy 0.5% O2 (5.49 ± 0.27) P < 0.01, 10 Gy 5% (14.07 ± 1.33) compared to 10 Gy 0.5% O2 (6.18 ± 0.43) P < 0.01, 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% (15.7 ± 1.33) compared to 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% (8.85 ± 1.74) P < 0.05, and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% (14.77 ± 1.39) compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 (5.18 ± 1.49) P < 0.01 (Figure 3).

In the OE33R cell line there was a significant increase in expression of calreticulin in response to 10 Gy (25.13 ± 1.96), 3 Gy × 2 Gy (12.5 ± 1.04), 3 Gy × 4 Gy (25.13 ± 2.07), and 3 Gy × 8 Gy (41.23 ± 1.02) compared to non-irradiated cells (6.55 ± 1.3), P < 0.05. There was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 (14.93 ± -1.94), 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 (20.3 ± 1.29) compared to non-irradiated cells at 5% O2 (10.42 ± 2.44) P < 0.05. There was also a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% O2 (15.93 ± 0.97), 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 (20.6 ± 1) compared to non-irradiated cells (6.78 ± 1.94) P < 0.01. There was also a significantly higher expression of calreticulin in response to 10 Gy normoxia (25.13 ± 1.96) compared to 10 Gy 5% O2 (15 ± 0.3) P < 0.01 and 10 Gy 0.5% O2 (10.77 ± 0.78) P < 0.001. There was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 4 Gy normoxia (25.13 ± 2.07) compared to 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 (14.93 ± 1.94) P < 0.05 and 3 Gy × 8 Gy normoxia (41.23 ± 1.02) compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 (10.77 ± 0.78) P < 0.05 (Figure 3).

In summary, severe hypoxia in combination with high dose radiation or hypofractionation under glucose deprivation appears to reduce DAMP expression. Interestingly, under mild hypoxia in combination with glucose deprivation, there is an increase in HMGB1 and CRT expression in the radiosensitive cell line but not the radioresistant cell line, suggesting that under glucose deprivation, tumour cell radiosensitivity is also a consideration for combination immunotherapy in order to enhance immunogenicity of the dying tumour cells.

In the OE33P cell line there was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy normoxia no glutamine (13.47 ± 0.41) and 3 Gy × 4 Gy normoxia no glutamine (4.26 ± 0.62) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy normoxia no glutamine (14.2+/-0.89) compared to 0 Gy normoxia no glutamine (1.68 ± 0.46) P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 respectively. There was significantly increased expression of HMGB1 in response to 2 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (9.76 ± 1.49), 10 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (17.8 ± 1.46), 3 Gy × 2 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (8.09 ± 0.61), 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (15.5 ± 1.06) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (15.3 ± 1.5) P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001 respectively. There was also increased expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (8.65 ± 1.63) compared to 0 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (2.56 ± 0.96) P < 0.01. There was increased expression of HMGB1 at 2 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (9.79 ± 1.49) compared to 2 Gy normoxia no glutamine (1.78 ± 0.17) P < 0.01 and 2 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (7.15 ± 0.82) P < 0.01. There was increased expression of HMGB1 at 10 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (17.8 ± 1.46) compared to 10 Gy normoxia no glutamine (13.47 ± 0.41) P < 0.01 and 10 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (2.54 ± 0.76) P < 0.001. There was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 2 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (8.09 ± 0.61) compared to 3 Gy × 2 Gy normoxia no glutamine (2.15 ± 0.21) P < 0.001 and 3 Gy × 2 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (1.91 ± 0.55) P < 0.001 and 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (15.5 ± 1.06) compared to 3 Gy × 4 Gy normoxia no glutamine (4.26 ± 0.65) P < 0.001 and 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (3.51 ± 0.92) P < 0.001. There was significantly less HMGB1 expressed at 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (8.65 ± 1.93) compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (15.3 ± 1.5) P < 0.001 and 3 Gy × 8 Gy normoxia no glutamine (14.2 ± 0.89) P < 0.001 (Figure 4).

In the OE33 R cell line, there was significantly higher expression of HMGB1 in response to 10 Gy normoxia no glutamine (17.53 ± 1.76), 3 Gy × 4 Gy normoxia no glutamine (13.05 ± 1.65), 3 Gy × 8 Gy normoxia no glutamine (17.1 ± 3.16) compared to 0 Gy normoxia no glutamine (2.85 ± 0.22) P < 0.05, P < 0.001, P < 0.01 respectively. There was significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (22.9 ± 2.9) compared to 0 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (4.66 ± 0.23) P < 0.05. There was significantly higher expression of HMGB1 at 10 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (11.7 ± 1.06), 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% no glutamine (11.57 ± 0.97) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (14.5 ± 2.25) compared to 0 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (2.75 ± 0.46) P < 0.001, P < 0.01, P < 0.05 respectively (Figure 4).

In the OE33P cell line there was a significant increase in expression of calreticulin no glutamine with 2 Gy at 5% O2 (9.18 ± 1.19), 10 Gy at 5% O2 (13.4 ± 1), 3 Gy × 2 Gy at 5% O2 (10.5 ± 0.32), 3 Gy × 4 Gy at 5% O2 (13.83 ± 1.86), compared to 0 Gy 5% O2 (4.46 ± 0.86) P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P < 0.001 respectively. There is a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 2 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (9.18 ± 1.19) and 2 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (8.1 ± 0.85) compared to 2 Gy normoxia (1.53 ± 0.22) P < 0.01, P < 0.001 respectively. There is a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 10 Gy 5% O2 (13.4 ± 1) compared to 10 Gy normoxia (3.22 ± 0.33) P < 0.001 and 10 Gy 0.05% O2 (3.94 ± 1.1) P < 0.001. There is a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 2 Gy 5% O2 (10.4 ± 0.32) compared to 3 Gy × 2 Gy normoxia (1.75 ± 0.17) P < 0.01 and 3 Gy × 2 Gy 0.5% O2 (3.18 ± 0.82) P < 0.001. The expression of calreticulin is significantly higher with 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (13.83 ± 1.86) and 3 Gy × 4 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (10.21 ± 1.42) compared to 3 Gy × 4 Gy normoxia (4.27 ± 0.24) P < 0.001. There was also a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (19.43 ± 2.76) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (10.48 ± 1.58) compared to 3 Gy × 8 Gy normoxia no glutamine (2.56 ± .44) P < 0.001 (Figure 4).

In the OE33R cell line there was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin in response to 10 Gy no glutamine (21.5 ± 1.19), 3 Gy × 2 Gy no glutamine (15.73 ± 1.04), 3 Gy × 4 Gy no glutamine (13.05 ± 1.65) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy no glutamine (17.7 ± 2.83) compared to 0 Gy no glutamine (4.68 ± 0.49) P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.05 respectively. There was a significantly higher expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 4 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (17.5 ± 2.75) and 3 Gy × 8 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (32.7 ± 3.67) compared to 0 Gy 5% O2 no glutamine (6.25 ± 0.58) P < 0.01, P < 0.05 respectively. There was an increased expression of calreticulin at 3 Gy × 8 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (17.87 ± 2.83) compared to 0 Gy 0.5% O2 no glutamine (3.76 ± 0.35) P < 0.05 (Figure 4).

In summary, similar to glucose deprivation there was significantly higher expression of HMGB1 and CRT under mild hypoxia and glutamine deprivation with higher bolus doses of radiation or hypofractionation in the radiosensitive cell line compared to the radioresistant cell line. Interestingly this was more pronounced under glutamine deprivation than glucose deprivation for these cells. In the radioresistant cells, there was similar expression of both HMGB1 and CRT irrespective of hypoxia severity or radiation dose.

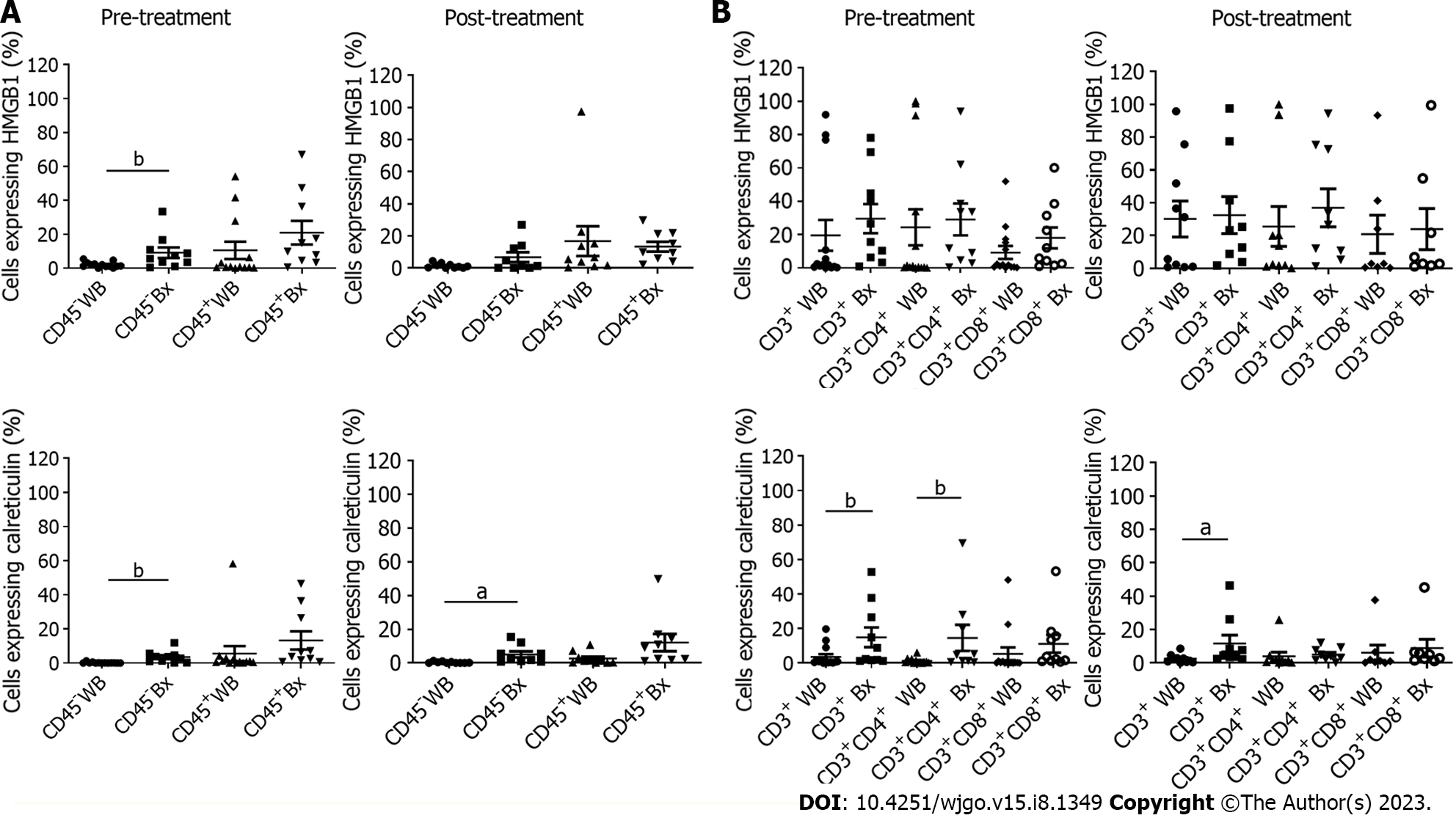

In order to determine the basal expression of DAMPs in ex vivo patient samples, blood and tumour biopsies were taken pre-conventional chemo(radio)therapy, the current standard of care in OAC. In order to determine the source of DAMP expression, CD45 was used to differentiate cells of the hematopoietic system from epithelial and endothelial cells within the tumour tissue. There was a higher expression of CD45+ HMGB1 in tumour tissue (20.95+/-6.99) compared to whole blood (10.56+/-5.09). There was a significantly higher expression of CD45- HMGB1 in tumour tissue (9.18+/-3.1) compared to whole blood (2+/-0.45) P < 0.01. There was a higher expression of CD45+ calreticulin in tumour tissue (13.29+/-5.31) compared to whole blood (5.6+/-4.4) and a significantly higher expression of CD45– calreticulin in tumour tissue (3.52+/-1.11) compared to whole blood (0.22+/-0.1) P < 0.01 (Figure 5A).

In the post-treatment samples, 7 of which were matched from pre-treatment samples, DAMP expression was assessed to determine if chemo(radiotherapy) induced immunogenic cell death. There was a higher expression of CD45+ HMGB1 in whole blood (16.83+/-9.24) compared to tumour tissue (13.35+/-3.1), with a higher expression of CD45- HMGB1 in tumour tissue (6.78+/-3.08) compared to whole blood (1.44+/-0.47). There was a higher expression of CD45+ calreticulin in tumour tissue (12.08+/-5.09) compared to whole blood (2.61+/-1.13) and also a significantly higher expression of CD45– calreticulin in tumour tissue (5.06+/-1.77) compared to whole blood (0.36+/-0.15) P < 0.05 (Figure 5A).

As the CD45+ populations were staining positive for these DAMPs, expression of DAMPs by T cells was explored, which to the author’s best knowledge has not been reported in OAC before. For pre-treatment samples, the expression of CD3+ HMGB1 was higher in tumour tissue (29.56+/-8.76) than in whole blood (19.58+/-9.23). There was also an increased expression of CD3+ CD4+ HMGB1 in tumour tissue (29.1+/-9.56) compared to whole blood (24.42+/-10.76). There was also a higher expression of CD3+ CD8+ HMGB1 in tumour tissue (18.01+/-6.28) compared to whole blood (9.24+/-3.91) (Figure 5B). The expression of CD3+ calreticulin was significantly higher in tumour tissue (18.26+/-5.78) compared to whole blood (3.56+/-1.61) P < 0.01. CD3+ CD4+ calreticulin was significantly higher in tumour tissue (14.59+/-7.59) than in whole blood (1.26+/-0.46) P < 0.01. There was also a higher expression of CD3+ CD8+ calreticulin in tumour tissue (11.15+/-5.14) compared to whole blood (5.33+/-3.66) (Figure 5B). For post-treatment samples, there was a higher expression of CD3+ HMGB1 in tumour tissue (32.44+/-11.28) compared to whole blood (30.11+/-10.97), CD3+CD4+ HMGB1 in tumour tissue (36.83+/-11.61) compared to whole blood (25.49+/-12.14) and CD4+ CD8+ HMGB1 in tumour tissue (23.91+/-12.57) compared to whole blood (20.75+/-11.62). There was a significantly higher expression of CD3+ calreticulin in tumour tissue (11.68+/-2.68) compared to whole blood (2.47+/-0.81) P < 0.05 (Figure 5B). There was a higher expression of CD3+ CD4+ calreticulin in tumour tissue (5.04+/-1.3) compared to whole blood (3.97+/-2.46) and also CD4+ CD8+ calreticulin in tumour tissue (8.87+/-5.25) compared to whole blood (6.15+/-4.57) (Figure 5B).

In summary, significantly higher levels of DAMPs are expressed in the tumour tissue compared to blood and this holds true for calreticulin post-treatment. Interestingly, T cells were found to express high levels of both HMGB1 and calreticulin. While CD3+ T cell expression of calreticulin is significantly higher in the tumour tissue compared to blood both pre- and post-treatment, CD3+ CD4+ T cells lose calreticulin expression post treatment. The impact of immunogenic cell death of T cells within the tumour microenvironment or the expression of DAMPs by T cells is unknown and this intriguing finding warrants further investigation.

In order to determine if conventional treatment strategies induce immunogenic cell death, matched pre and post patient whole blood (n = 5) was compared. CD45 is a critical regulator of signalling thresholds in immune cells and is moving rapidly back into the spotlight as a drug target and central regulator involved in autoimmunity and antiviral immunity. In this section the expression of DAMPs was assessed on CD45+ and CD45- cells in pre- and post-treatment samples (Figure 6A). There was a higher expression of CD45+ HMGB1 on post-treatment whole blood (30+/-17.09) compared to pre-treatment (12.55+/-10.41) and a higher expression of CD45- HMGB1 (1.99+/-0.92) on post-treatment whole blood compared to pre-treatment samples (0.27+/-0.19) (Figure 6A). Similarly, there was a higher expression of CD45+ calreticulin post-treatment (0.99+/-0.57) compared to pre-treatment samples (0.49+/-0.15). There was also an increased expression of CD45- calreticulin on post-treatment whole blood (0.55+/-0.26) compared to pre-treatment samples (0.16+/-0.09) (Figure 6A).

As we again observed higher expression of HMGB1 and calreticulin on CD45+ immune cells, we assessed whether standard of care regimens could affect expression of DAMPs on T cells.

There was a significantly increased expression of CD3+ HMGB1 in whole blood post-treatment (66.46+/-11.25) compared to pre-treatment samples (2.82+/-2.02) P < 0.05 (Figure 6B). The expression of CD3+ CD4+ HMGB1 was higher in post-treatment whole blood (64.66+/-19.55) compared to pre-treatment samples (3.16+/-2.53). There was a significantly higher expression of CD4+ CD8+ HMGB1 in post-treatment whole blood (59.5+/-10.1) compared to pre-treatment (5.66+/-4.8) P < 0.01. There was a higher expression of T cell calreticulin in post-treatment whole blood compared to pre-treatment but this was not significant (Figure 6B).

In summary, the chemoradiotherapy regimen CROSS induces HMGB1 and calreticulin expression by T cells, suggesting that T cells may be undergoing immunogenic cell death as a result, the ultimate outcome of immune cell death in this setting is unknown as to whether the balance is tipped in favour of immune stimulation or suppression.

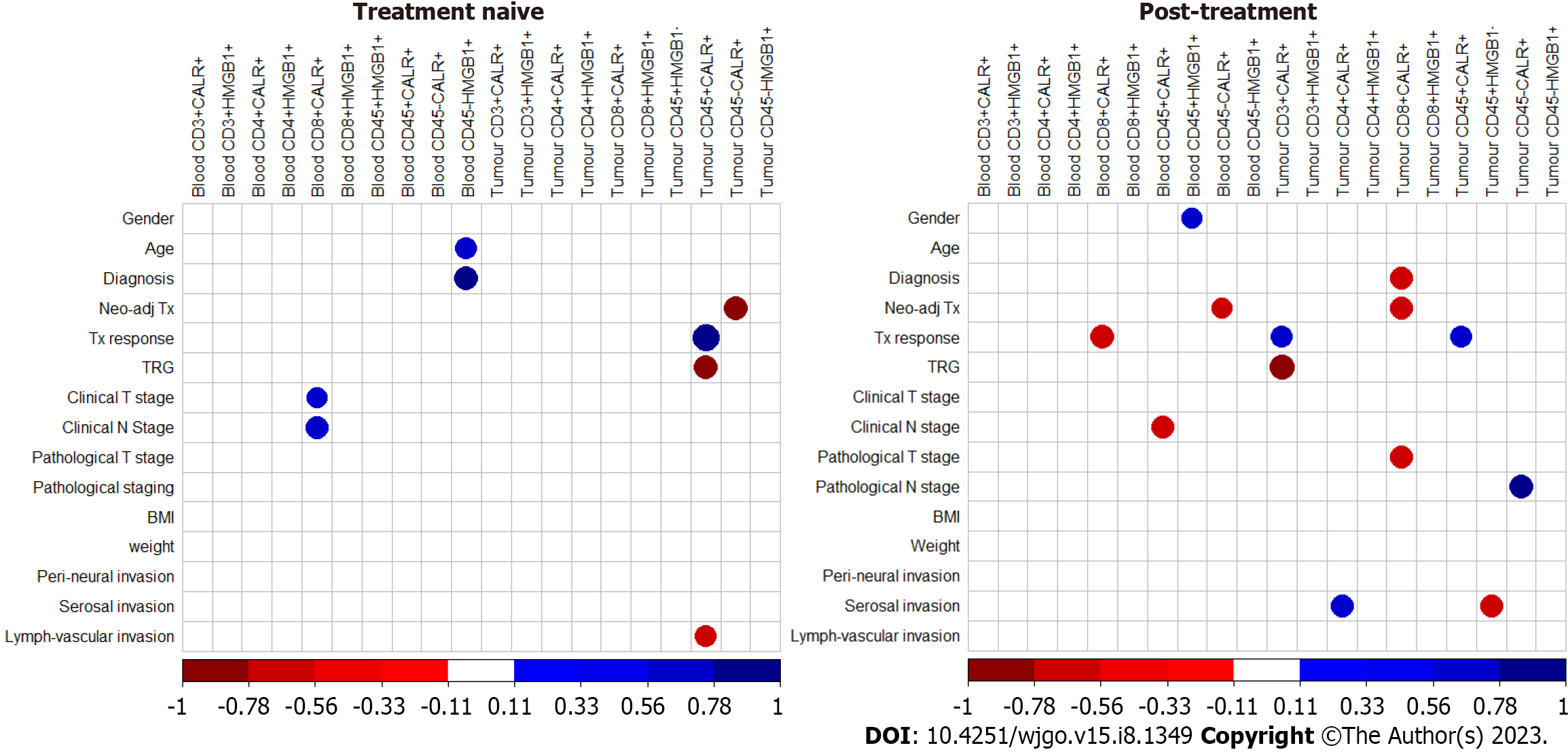

In order to determine if DAMP expression by haematopoietic cells or non- haematopoietic cells correlated with clinical outcome, correlations were performed with clinical measures. The expression of CD45+ calreticulin (CALR) on treatment naïve tumour tissue positively correlates with the tumour regression grade (TRG) and also with lymphovascular invasion. The expression of CD45- calreticulin positively correlates with the neoadjuvant treatment modality received pre-operatively (Figure 7). Tumour CD8+ calreticulin+ positively correlated with tumour overall clinical stage, neoadjuvant treatment modality pathological T stage and tumour CD45+ HMGB1- positively correlates with serosal invasion. Tumour CD3+ calreticulin+ positively correlated with TRG (Figure 7).

There remains significant difficulties in synergising the effects of radiation with adequate ongoing immune responses, despite both demonstrating significant efficacy in isolation. The introduction of immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, have made significant inroads in capitalising on the immunostimulatory role of radiation in cancer patients but these gains remain small. Radiation is known to induce immunostimulatory tumour cell death and the defining molecular hallmark of this immunogenic cell death (ICD) is the release of host-derived, immune-activating molecules known as DAMPs from the dying cells. These ectopically expressed DAMPs are postulated to function as signal zero to engage pattern recognition receptors on professional antigen-presenting cells (e.g., dendritic cells) and other innate immune cells. Solid neoplasms are highly heterogenous and develop, progress and respond to local and systemic therapies in the context of intricate crosstalk with the host immune system[24]. It must be borne in mind that distinct phenotypic and behavioural features generally co-exist, and often multiple non-transformed cells are co-opted by growing cancers to support their needs. There is accumulating evidence that the efficacy of most chemo- and radiotherapeutic agents commonly employed in the clinic are dependent on the propagation of anti-tumour immune responses[25]. Consequently, conventional therapeutics such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy can evoke a therapeutically relevant, adaptive immune response against malignant cells leading to immunogenic cell death. Alterations in the phenotype and microenvironment of tumour cells after exposure to irradiation, chemotherapeutic agents and immune modulating agents renders the tumour more immunogenic, with the induction of abscopal effects and this varies widely with the model systems and the radiation or pharmacological regimen utilized[26]. There have been previous studies in the literature suggesting interactions and synergies of radiation therapy that are essentially dependent on the induction of type-I interferons (produced by the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator of interferon genes axis), which consequently promote maturation of antigen presenting cells and priming and mobilisation of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells to the TME. High single doses of radiation such as 10-20 Gy have been shown to induce such effects[27]. However, on the contrary a recent study suggests that fractionated dosing such as 3 Gy × 8 Gy may be optimal[28]. In reality, clinically abscopal tumour lesion responses remain elusive and exceedingly rare, likely because comparable hypofractionation (fractions of > 5 Gy) are rarely used in the radiotherapeutic routine in patients. However, it has been demonstrated that in the tumour microenvironment, DAMPs can be ligands for toll-like receptors (TLRs) expressed on immune cells and induce cytokine production and T-cell activation[29]. Moreover, DAMPs released from tumour cells can directly activate tumour-expressed TLRs that induce chemoresistance, migration, invasion, and metastasis[29].

Our findings of significantly higher calreticulin expression following radiation treatment in the radioresistant OE33R tumour cells when compared to the radiosensitive OE33P cell line suggests an immunogenic type of cell death induced by radiation in the radioresistant cell line providing a foundation for immune modulating agents to enhance the established anti-tumour response, particularly with adverse biology such as radioresistance. There were similar findings for HMGB1 with a higher expression of HMGB1 in the OE33R cell line with bolus dosing, however, there was a significantly higher expression of HMGB1 with fractionated dosing regimens in the OE33P radiosensitive cell line. The increased expression of both DAMPS post radiotherapy in vivo and ex vivo is promising in the OAC setting, indicating that OAC may be an immunogenic tumour-type and therefore a potential target for systemic immunotherapies in combination with radiotherapy. In addition to this, the increased expression of calreticulin and HMGB1 post radiation with hypoxia, notably 5% O2 and nutrient deprivation in OE33P cell line, represent further exciting data and suggest that oesophageal cancer may be a viable phenotype for enhancing the anti-tumour immune response. On the contrary, it is also important to note that the properties of the intrinsic tumour microenvironment, such as hypoxia or nutrient deprivation, endemic of tumours, could alter the action of ICD stressors and modulate the immunomodulatory properties of DAMPs[30]. Furthermore, it was previously demonstrated that hypoxia leads to HMGB1 release, which can contribute to tumour invasiveness[31]. DAMPs are released from cells under stress due to these harsh conditions of the tumour microenvironment including nutrient deprivation and hypoxia, or secondary to treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and when released can have a double-edged sword activating innate immunity, providing a pathway to a systemic inflammatory response or can be manipulated in regulating inflammation in the tumour microenvironment, promoting angiogenesis and increasing autophagy with immune evasion and resistance to apoptotic tumour cell death, facilitating progression and or dissemination[32].

The use of immune checkpoint blockade to shift the balance in favour of anti-tumour immunity is a promising approach, however the effects of this harsh micro-environment on the expression of DAMPs is yet to be determined. Our findings demonstrated that the increased expression of DAMPs in vitro under conditions of the TME is intriguing and may indicate that immunogenic cell death is still occurring in the harsh TME which could be a mechanism to enhance anti-tumour immunity in an immunosuppressive milieu.

There is evidence in the literature of high calreticulin levels in cancer cells correlating with favourable disease outcome in a cohort of 68 neuroblastoma patients as a consequence of radiation therapy inducing immunogenic cell death and also in a cohort of lung cancer patients[33]. In addition to this, increased calreticulin expression by cancer cells has been associated with tumour infiltration by CD45RO+ memory T cells and improved 5-year overall survival in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma[34]. HMGB1 has been demonstrated to have both pro and anti-tumour modulating effects and is overexpressed in precancerous states such as liver cirrhosis and gastric dysplasia[35], as well as in a wide range of tumours and may induce inflammatory responses that promote tumourigenesis and/or progression[35,36]. HMGB1 triggers the recruitment of neutrophils, subsequent inflammation and amplification of injury in multiple injury models[37]. In one study, high levels of HMGB1 expression in cancer cells have been shown to correlate with improved overall survival in 88 patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma subjected to neo-adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgical resection, as well as in 76 subjects with resectable gastric adenocarcinoma[38]. However, in colorectal cancer, elevated HMGB1 in serum correlated with incidence, progression or unfavourable disease outcome in a cohorts 219 colorectal cancer patients demonstrating the diverse prognostic or predictive value of high intratumoural and circulating levels of HMGB1[34]. Interestingly, in our study, there were two distinct subgroups with high and low expressors of DAMPs, and this correlated with tumour regression grade and lymphatic invasions. Patients who were high expressors of HMGB1 had a significantly better TRG (1-2) compared to low expressors. In the same vein, patients who had an increase in calreticulin post treatment had a better TRG (1-2), which may indicate a potential prognostic utility for these DAMPs in OAC.

One of the key findings of this work is the increase in expression of calreticulin and HMGB1 following conventional therapies by CD45+ cells and CD3+ T cells, which may indicate ICD of immune cells as a consequence of systemic and local treatment modalities. This could have immunostimulatory effects or have a direct effect on dampening immune function by T cell killing. The ultimate outcome of this on anti-tumour immunity is unknown but clearly warrants more research. Despite advances in our knowledge on the impact of conventional therapies on anti-tumour responses, there are many unknown effects of radiation on T cells and how this could impact response to radiation-induced anti-tumour immunity. HMGB1 is involved in various intracellular (transcription, autophagy) and extracellular (inflammation, autoimmunity) processes with paradoxical and conflicting results in the literature and it is still unclear whether HMGB1 mainly acts as an oncogene or a tumour suppressor[39]. Mechanistically, intracellular HMGB1 induces radiation tolerance in tumour cells by promoting DNA damage repair and autophagy. Extracellular HMGB1 plays a more intricate role in radiation-related immune responses, wherein it not only stimulates the anti-tumour immune response by facilitating the recognition of dying tumor cells but is also involved in maintaining immunosuppression. Factors that potentially affect the role of HMGB1 such as chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in the context of OAC may also have a role in the context of possible therapeutic applications, to develop effective and targeted radio-sensitization therapies[40].

A sentinel study also demonstrated that suppression of dendritic cells by HMGB1 is associated with lymph node metastasis of human colon cancer The 8 nodal metastasis-positive cases showed higher nodal HMGB1 concentrations in lymph node tissues and lower CD205-positive nodal dendritic cell numbers than those in the 8 metastasis-negative cases[41]. Furthermore, soluble HMGB1 is a promising biomarker for prediction of therapy response and prognosis in advanced NSCLC patients with high concentrations of HMGB1 at cycles 2 and 3 associated with shorter overall survival in NSCLC patients[42].

Similarly, there is a gap in research knowledge on how radiotherapy can affect T cells responding to immune checkpoint inhibitors and this is the first paper to specifically look at DAMP expression by T cells in OAC patients in the context of conventional therapeutic strategies.

A deeper understanding of the diverse roles of DAMPs and the implications of DAMP expression on T cells is needed to fully exploit therapeutic strategies, and it is postulated that these therapeutic approaches might incorporate both activation and inhibition of DAMP signalling pathways. In addition to this, approaches that may combined with signature-based proxies of hypoxia to further dissect the turbulent hypoxia and nutrient deprivation-immune relationship to elicit symbiotic responses between radiation and ICB are warranted. Furthermore, drawing conclusions about the clinical applicability of DAMP expression on T cells as biomarkers is currently still restricted by the small size of these studies, heterogeneous patient populations (i.e., disease stage), and treatment differences such as chemoradiotherapy combinations and dosing and therefore further work is needed to elucidate mechanistic and therapeutic potentials. Notwithstanding, our body of work shows promise in predicting tumour regression grade and tumour responses in OAC. Similarly, these findings suggest the potential of DAMPs in synergising radiation and propagating an established immune response in OAC.

The incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC) is increasing exponentially annually as a consequence of obesity. The current therapeutics remain chemo(radio)therapy with mixed responses. The purpose of this work is to determine baseline damage associated molecular pattern (DAMP) expression in OAC patients as well as the effects of chemo

To identify new therapeutic strategies in OAC.

This study aims to interrogate OAC DAMP expression.

Patient tumour and serum samples were assessed for DAMP expression as well as tumour cell lines to mimic the tumour microenvironment.

Conventional therapies increase DAMP expression.

OAC is an immunogenic cancer and must be exploited to harness immune mediated anti tumour responses.

This is the first study of its kind in esophageal cancer looking at the baseline expression of DAMPs which is viewed as a surrogate marker of immunogenicity. Furthermore, it looks at the effects of conventional therapies on the immunogenicity of OAC.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Immunology

Country/Territory of origin: Ireland

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Guo Z, United States; Mohamed SY, Egypt S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Chen HHW, Kuo MT. Improving radiotherapy in cancer treatment: Promises and challenges. Oncotarget. 2017;8:62742-62758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP, Richel DJ, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Hospers GA, Bonenkamp JJ, Cuesta MA, Blaisse RJ, Busch OR, ten Kate FJ, Creemers GJ, Punt CJ, Plukker JT, Verheul HM, Spillenaar Bilgen EJ, van Dekken H, van der Sangen MJ, Rozema T, Biermann K, Beukema JC, Piet AH, van Rij CM, Reinders JG, Tilanus HW, van der Gaast A; CROSS Group. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3288] [Cited by in RCA: 4028] [Article Influence: 309.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sato H, Demaria S, Ohno T. The role of radiotherapy in the age of immunotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2021;51:513-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Olivares-Urbano MA, Griñán-Lisón C, Marchal JA, Núñez MI. CSC Radioresistance: A Therapeutic Challenge to Improve Radiotherapy Effectiveness in Cancer. Cells. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fucikova J, Moserova I, Urbanova L, Bezu L, Kepp O, Cremer I, Salek C, Strnad P, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Spisek R. Prognostic and Predictive Value of DAMPs and DAMP-Associated Processes in Cancer. Front Immunol. 2015;6:402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ashrafizadeh M, Farhood B, Eleojo Musa A, Taeb S, Najafi M. Damage-associated molecular patterns in tumor radiotherapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;86:106761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Spel L, Boelens JJ, Nierkens S, Boes M. Antitumor immune responses mediated by dendritic cells: How signals derived from dying cancer cells drive antigen cross-presentation. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e26403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gogolák P, Réthi B, Hajas G, Rajnavölgyi E. Targeting dendritic cells for priming cellular immune responses. J Mol Recognit. 2003;16:299-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gold LI, Eggleton P, Sweetwyne MT, Van Duyn LB, Greives MR, Naylor SM, Michalak M, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Calreticulin: non-endoplasmic reticulum functions in physiology and disease. FASEB J. 2010;24:665-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Michalak M, Corbett EF, Mesaeli N, Nakamura K, Opas M. Calreticulin: one protein, one gene, many functions. Biochem J. 1999;344 Pt 2:281-292. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Grover A, Troudt J, Foster C, Basaraba R, Izzo A. High mobility group box 1 acts as an adjuvant for tuberculosis subunit vaccines. Immunology. 2014;142:111-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Walle T, Martinez Monge R, Cerwenka A, Ajona D, Melero I, Lecanda F. Radiation effects on antitumor immune responses: current perspectives and challenges. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758834017742575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Petrova V, Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli M, Melino G, Amelio I. The hypoxic tumour microenvironment. Oncogenesis. 2018;7:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 480] [Cited by in RCA: 715] [Article Influence: 102.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Whiteside TL. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008;27:5904-5912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1334] [Cited by in RCA: 1714] [Article Influence: 100.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Corrigendum for de Oliveira Otto et al. Serial measures of circulating biomarkers of dairy fat and total and cause-specific mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2018;108:476-84. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108:643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Emami Nejad A, Najafgholian S, Rostami A, Sistani A, Shojaeifar S, Esparvarinha M, Nedaeinia R, Haghjooy Javanmard S, Taherian M, Ahmadlou M, Salehi R, Sadeghi B, Manian M. The role of hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment and development of cancer stem cell: a novel approach to developing treatment. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 93.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Muz B, de la Puente P, Azab F, Azab AK. The role of hypoxia in cancer progression, angiogenesis, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Hypoxia (Auckl). 2015;3:83-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 842] [Cited by in RCA: 1376] [Article Influence: 137.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gkiouli M, Biechl P, Eisenreich W, Otto AM. Diverse Roads Taken by (13)C-Glucose-Derived Metabolites in Breast Cancer Cells Exposed to Limiting Glucose and Glutamine Conditions. Cells. 2019;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lambert AW, Pattabiraman DR, Weinberg RA. Emerging Biological Principles of Metastasis. Cell. 2017;168:670-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2147] [Cited by in RCA: 2145] [Article Influence: 268.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Krombach J, Hennel R, Brix N, Orth M, Schoetz U, Ernst A, Schuster J, Zuchtriegel G, Reichel CA, Bierschenk S, Sperandio M, Vogl T, Unkel S, Belka C, Lauber K. Priming anti-tumor immunity by radiotherapy: Dying tumor cell-derived DAMPs trigger endothelial cell activation and recruitment of myeloid cells. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1523097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhou J, Wang G, Chen Y, Wang H, Hua Y, Cai Z. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy: Present and emerging inducers. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:4854-4865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 485] [Article Influence: 80.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Adjemian S, Oltean T, Martens S, Wiernicki B, Goossens V, Vanden Berghe T, Cappe B, Ladik M, Riquet FB, Heyndrickx L, Bridelance J, Vuylsteke M, Vandecasteele K, Vandenabeele P. Ionizing radiation results in a mixture of cellular outcomes including mitotic catastrophe, senescence, methuosis, and iron-dependent cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lynam-Lennon N, Reynolds JV, Pidgeon GP, Lysaght J, Marignol L, Maher SG. Alterations in DNA repair efficiency are involved in the radioresistance of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Radiat Res. 2010;174:703-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z. Roles of the immune system in cancer: from tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes Dev. 2018;32:1267-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 765] [Cited by in RCA: 1388] [Article Influence: 198.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Carvalho HA, Villar RC. Radiotherapy and immune response: the systemic effects of a local treatment. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018;73:e557s. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Derer A, Deloch L, Rubner Y, Fietkau R, Frey B, Gaipl US. Radio-Immunotherapy-Induced Immunogenic Cancer Cells as Basis for Induction of Systemic Anti-Tumor Immune Responses - Pre-Clinical Evidence and Ongoing Clinical Applications. Front Immunol. 2015;6:505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Storozynsky Q, Hitt MM. The Impact of Radiation-Induced DNA Damage on cGAS-STING-Mediated Immune Responses to Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Habets TH, Oth T, Houben AW, Huijskens MJ, Senden-Gijsbers BL, Schnijderberg MC, Brans B, Dubois LJ, Lambin P, De Saint-Hubert M, Germeraad WT, Tilanus MG, Mottaghy FM, Bos GM, Vanderlocht J. Fractionated Radiotherapy with 3 x 8 Gy Induces Systemic Anti-Tumour Responses and Abscopal Tumour Inhibition without Modulating the Humoral Anti-Tumour Response. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jang GY, Lee JW, Kim YS, Lee SE, Han HD, Hong KJ, Kang TH, Park YM. Interactions between tumor-derived proteins and Toll-like receptors. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:1926-1935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yan W, Chang Y, Liang X, Cardinal JS, Huang H, Thorne SH, Monga SP, Geller DA, Lotze MT, Tsung A. High-mobility group box 1 activates caspase-1 and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma invasiveness and metastases. Hepatology. 2012;55:1863-1875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tsung A, Klune JR, Zhang X, Jeyabalan G, Cao Z, Peng X, Stolz DB, Geller DA, Rosengart MR, Billiar TR. HMGB1 release induced by liver ischemia involves Toll-like receptor 4 dependent reactive oxygen species production and calcium-mediated signaling. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2913-2923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 455] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Boone BA, Lotze MT. Targeting damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs) and DAMP receptors in melanoma. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1102:537-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Garg AD, Elsen S, Krysko DV, Vandenabeele P, de Witte P, Agostinis P. Resistance to anticancer vaccination effect is controlled by a cancer cell-autonomous phenotype that disrupts immunogenic phagocytic removal. Oncotarget. 2015;6:26841-26860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Fahmueller YN, Nagel D, Hoffmann RT, Tatsch K, Jakobs T, Stieber P, Holdenrieder S. Immunogenic cell death biomarkers HMGB1, RAGE, and DNAse indicate response to radioembolization therapy and prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2349-2358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Chung HW, Lee SG, Kim H, Hong DJ, Chung JB, Stroncek D, Lim JB. Serum high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) is closely associated with the clinical and pathologic features of gastric cancer. J Transl Med. 2009;7:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Brezniceanu ML, Völp K, Bösser S, Solbach C, Lichter P, Joos S, Zörnig M. HMGB1 inhibits cell death in yeast and mammalian cells and is abundantly expressed in human breast carcinoma. FASEB J. 2003;17:1295-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Huebener P, Pradere JP, Hernandez C, Gwak GY, Caviglia JM, Mu X, Loike JD, Schwabe RF. The HMGB1/RAGE axis triggers neutrophil-mediated injury amplification following necrosis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:539-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Suzuki Y, Mimura K, Yoshimoto Y, Watanabe M, Ohkubo Y, Izawa S, Murata K, Fujii H, Nakano T, Kono K. Immunogenic tumor cell death induced by chemoradiotherapy in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3967-3976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hubert P, Roncarati P, Demoulin S, Pilard C, Ancion M, Reynders C, Lerho T, Bruyere D, Lebeau A, Radermecker C, Meunier M, Nokin MJ, Hendrick E, Peulen O, Delvenne P, Herfs M. Extracellular HMGB1 blockade inhibits tumor growth through profoundly remodeling immune microenvironment and enhances checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Liao Y, Liu S, Fu S, Wu J. HMGB1 in Radiotherapy: A Two Headed Signal Regulating Tumor Radiosensitivity and Immunity. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:6859-6871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Kusume A, Sasahira T, Luo Y, Isobe M, Nakagawa N, Tatsumoto N, Fujii K, Ohmori H, Kuniyasu H. Suppression of dendritic cells by HMGB1 is associated with lymph node metastasis of human colon cancer. Pathobiology. 2009;76:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Handke NA, Rupp ABA, Trimpop N, von Pawel J, Holdenrieder S. Soluble High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) Is a Promising Biomarker for Prediction of Therapy Response and Prognosis in Advanced Lung Cancer Patients. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |