Published online Nov 15, 2023. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v15.i11.1874

Peer-review started: June 24, 2023

First decision: August 8, 2023

Revised: August 20, 2023

Accepted: September 6, 2023

Article in press: September 6, 2023

Published online: November 15, 2023

Processing time: 144 Days and 3.6 Hours

The prognosis of many patients with distant metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) improved after they survived for several months. Compared with tradi

To evaluate CS of distant metastatic HCC patients.

Patients diagnosed with distant metastatic HCC between 2010 and 2015 were extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis were used to identify risk factors for overall survival (OS), while competing risk model was used to identify risk factors for cancer-specific survival (CSS). Six-month CS was used to calculate the probability of survival for an additional 6 mo at a specific time after initial diagnosis, and standardized difference (d) was used to evaluate the survival differences between subgroups. Nomograms were constructed to predict CS.

Positive α-fetoprotein expression, higher T stage (T3 and T4), N1 stage, non-primary site surgery, non-chemotherapy, non-radiotherapy, and lung metastasis were independent risk factors for actual OS and CSS through univariate and multivariate analysis. Actual survival rates decreased over time, while CS rates gradually increased. As for the 6-month CS, the survival difference caused by chemotherapy and radiotherapy gradually disappeared over time, and the survival difference caused by lung metastasis reversed. Moreover, the influence of age and gender on survival gradually appeared. Nomograms were fitted for patients who have lived for 2, 4 and 6 mo to predict 6-month conditional OS and CSS, respectively. The area under the curve (AUC) of nomograms for conditional OS decreased as time passed, and the AUC for conditional CSS gradually increased.

CS for distant metastatic HCC patients substantially increased over time. With dynamic risk factors, nomograms constructed at a specific time could predict more accurate survival rates.

Core Tip: Distant metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients demonstrate high hazard ratios for death in the first few months, which makes survival estimates at the time of initial diagnosis inaccurate. Conditional survival (CS) which takes into account changes in survival risk could be used to describe dynamic survival probabilities. We conducted a population-based study to assess CS for distant metastatic HCC patients. Compared with actual survival rate for HCC patients which gradually decreased after initial diagnosis, CS rate substantially increased over time. With dynamic risk factors, nomograms were constructed to predict more accurate CS at different time after initial diagnosis.

- Citation: Yang YP, Guo CJ, Gu ZX, Hua JJ, Zhang JX, Shi J. Conditional survival probability of distant-metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma: A population-based study. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2023; 15(11): 1874-1890

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v15/i11/1874.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v15.i11.1874

Primary liver cancer was the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide in 2020, with approximately 906 000 new cases and 830 000 deaths[1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most frequent primary liver cancer, accounting for 75%–85% of the cases. HCC represents a growing health threat with annual mortality rates increasing by 2%–3% per year from 2003 to 2012 and a 43% increase in the rate of death from 2000 to 2016 in the USA[2,3]. Due to high metastatic potential, 14.0%–36.7% of HCC patients already had extrahepatic metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis, and the incidence of distant metastases in patients with HCC was about 13.5%[4-7]. The prognosis in HCC patients with extrahepatic metastasis was poorer than the prognosis of early-stage patients. Over the past three decades, the outcome of patients with advanced HCC has substantially improved due to better selection of appropriate treatments and advances in effective treatment[8-10]. For example, the small molecule targeted drug of sorafenib has been shown to extend life expectancy by nearly 3 mo[11,12]. However, extrahepatic metastatic HCC patients still have poor survival with a median expected survival time of only 6–8 mo or a 25% survival rate at 1 year[13].

With high mortality rate and poor prognosis, distant metastatic HCC patients would demonstrate high hazard ratios for death in the first few months, which makes survival estimates at the time of initial diagnosis inaccurate. Conditional survival (CS) is a concept that takes into account changes in survival risk and could be used to describe dynamic survival probabilities[14]. Previous studies have reported CS of breast cancer, glioma, lung cancer, colorectal cancer and other cancers[15-19]. CS studies of HCC patients have also been published, but these studies did not categorize the patients according to clinical stage[20-22]. As distant metastatic HCC patients have poorer survival than those in early stage, the CS estimates would also be different. Therefore, a study of dynamic CS analysis in patients with distant metastatic HCC is meaningful.

In this study, we calculated the dynamic survival probability for patients with distant metastatic HCC using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. Moreover, nomograms were constructed to predict CS of distant metastatic HCC patients at different time after initial diagnosis.

Data of primary diagnosed HCC patients from 2010 to 2015 were retrieved from the SEER database Program 17 registries (https://seer.cancer.gov/). Data were included following these criteria: (1) Age> 18 years; (2) patients were pathologically diagnosed with stage IVB HCC; (3) HCC was the only primary cancer; and (4) complete follow-up and survival data. Patients were excluded if the diagnosis was made only at autopsy. Those patients with incomplete American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging, α-fetoprotein (AFP) expression information, and unknown death reason were all excluded. Marital status included married (married and having domestic partner), single (never married), and separated (separated, divorced or widowed). The tumor size mentioned in this study referred to the size of the primary tumor. Surgery referred to surgery of the primary site.

In this study, overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the start of randomized treatment to death due to any reason, and cancer-specific survival (CSS) was defined as the time from the start of randomized treatment to death due to a specific disease. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression model were built to evaluate associations between features and OS, while Fine–Gray competing risk regression model was used to assess associations between features and CSS. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Cumulative incidence function curves were used to describe difference of mortality probability in subgroups.

CS analysis was applied to assess the possibility of additional survival for patients who have survived for specific months. Here, an additional 6-months’ survival (CS6) was calculated as: CS6 = S(x + 6)/S(x), which means CS6 among patients who have survived 2 mo from the date of diagnosis was calculated by dividing the survival at 8 mo by the survival at 2 mo. Based on variables selected by the multivariate Cox regression model and the competing risk model, nomograms for OS and CSS were fitted to estimate the CS6 of distant metastatic HCC patients, respectively. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC) were used to evaluate the performance of these nomograms.

Differences in CS among subgroups were calculated using the standardized differences (d) method, with the formula below[23]

The value of standardized differences can be divided into four conditions: |d| < 0.1 shows no difference in each group; 0.1 ≤ |d| < 0.3 shows a small difference; 0.3 ≤ |d| < 0.5 shows a moderate difference; and |d| ≥ 0.5 shows a significant difference. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used in all analyses. The statistical analysis was conducted using R software (packages: survival, cmprsk, rms, and timeROC).

A total of 1502 patients were included in the study (Table 1). The median age of these patients was 61 years (interquartile range: 56–68 years), 81.89% were male, and 65.11% of the patients were white. About half of the patients (49.40%) were married. Most patients were diagnosed with positive AFP expression (84.29%) and had a primary tumor size > 5 cm (72.70%). For TNM staging, > 50% patients were diagnosed in the T3 stage (n = 783, 52.13%), and > 60% were diagnosed without lymph nodes metastasis (N0, n = 1031, 68.64%). Consistent with previous study, lung metastasis (n = 553, 36.82%) was more frequent than other distant metastasis sites, including bone (n = 430, 28.63%) and brain (n = 27, 1.80%). Over half of the patients received chemotherapy, while few received primary-site surgery (n = 82, 5.46%) and radiotherapy (n = 302, 20.11%). The median survival time was only 4 (range, 1–117) mo, and 1457 (97.0%) patients died during the follow-up time and 1379 (94.65%) of them died because of HCC.

| Characteristics | n | % |

| Age, yr | ||

| < 55 | 299 | 19.91 |

| 55-65 | 656 | 43.68 |

| ≥ 65 | 547 | 36.42 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1230 | 81.89 |

| Female | 272 | 18.11 |

| Race | ||

| White | 978 | 65.11 |

| Black | 237 | 15.78 |

| Other | 287 | 19.11 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 405 | 26.96 |

| Married | 742 | 49.40 |

| Separated | 355 | 23.64 |

| AFP expression | ||

| Positive | 1266 | 84.29 |

| Negative | 236 | 15.71 |

| Tumor size | ||

| ≤ 5 cm | 410 | 27.30 |

| > 5 cm | 1092 | 72.70 |

| T stage | ||

| T1 | 337 | 22.44 |

| T2 | 216 | 14.38 |

| T3 | 783 | 52.13 |

| T4 | 166 | 11.05 |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 1031 | 68.64 |

| N1 | 471 | 31.36 |

| Surgery | ||

| No | 1420 | 94.54 |

| Yes | 82 | 5.46 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| No/unknown | 691 | 46.01 |

| Yes | 811 | 53.99 |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| No/unknown | 1200 | 79.89 |

| Yes | 302 | 20.11 |

| Lung metastasis | ||

| No | 949 | 63.18 |

| Yes | 553 | 36.82 |

| Bone metastasis | ||

| No | 1072 | 71.37 |

| Yes | 430 | 28.63 |

| Brain metastasis | ||

| No | 1475 | 98.20 |

| Yes | 27 | 1.80 |

| Survival status | ||

| Alive | 45 | 3.00 |

| Other cause death | 78 | 5.19 |

| Cancer specific death | 1379 | 91.81 |

| Total | 1502 | 100 |

The 2-, 6- and 12-month OS rates were 64.14%, 32.79% and 17.48%, while the 2-, 6- and 12-month CSS rates were 65.89%, 34.77% and 19.16%, respectively (Figure 1). From the results of univariate analysis: positive AFP expression, tumor size (> 5 cm), higher T stage (T3 and T4), N1 stage, non-primary site surgery, non-chemotherapy, non-radiotherapy, and lung metastasis were risk factors for OS, and these factors were also risk factors for CSS through the Gray’s test (Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). Race was also identified to be associated with CSS through the Gray’s test. For multivariate analysis, positive AFP expression, higher T stage (T3 and T4), N1 stage, non-primary site surgery, non-chemotherapy, non-radiotherapy, lung metastasis, and bone metastasis were independent risk indicators of OS, and they were also independent risk indicators of CSS through the competing risk model (Table 2). Bone metastasis was only identified as a risk factor in multivariate analysis, which may have been influenced by radiotherapy. Patients with bone metastasis who received radiotherapy had better survival rates and less cancer-specific mortality rates before 22 mo compared with patients without bone metastasis and bone metastatic patients without radiotherapy (Supplementary Figure 3).

| Characteristics | Overall survival | Cancer-specific survival | ||

| HR | P value | HR | P value | |

| Age, yr | ||||

| < 55 | ||||

| 55-65 | 1.03 (0.89-1.19) | 0.67 | 0.98 (0.85-1.13) | 0.78 |

| ≥ 65 | 1.09 (0.94-1.26) | 0.27 | 1.02 (0.88-1.19) | 0.77 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | ||||

| Male | 1.1 (0.96-1.26) | 0.18 | 1.07 (0.93-1.24) | 0.35 |

| Race | ||||

| Black | ||||

| White | 1.03 (0.89-1.2) | 0.67 | 1.09 (0.93-1.27) | 0.29 |

| Other | 1.12 (0.93-1.34) | 0.23 | 1.2 (0.99-1.45) | 0.063 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | ||||

| Single | 1.00 (0.88-1.14) | 0.96 | 0.95 (0.83-1.08) | 0.42 |

| Separated | 0.93 (0.82-1.07) | 0.31 | 0.86 (0.75-0.99) | 0.038 |

| AFP expression | ||||

| Negative | ||||

| Positive | 1.35 (1.17-1.56) | 5.02E-05 | 1.33 (1.16-1.52) | 5.70E-05 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| > 5 cm | ||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 0.86 (0.74-1.00) | 0.057 | 0.97 (0.83-1.13) | 0.69 |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | ||||

| T2 | 1.15 (0.95-1.39) | 0.16 | 0.98 (0.8-1.2) | 0.85 |

| T3 | 1.27 (1.1-1.46) | 1.03E-03 | 1.24 (1.07-1.42) | 3.30E-03 |

| T4 | 1.27 (1.04-1.54) | 0.18 | 1.29 (1.07-1.56) | 7.30E-03 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | ||||

| N1 | 1.19 (1.06-1.33) | 3.89E-03 | 1.12 (0.99-1.27) | 0.062 |

| Surgery | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 0.42 (0.32-0.54) | 7.65E-12 | 0.51 (0.41-0.64) | 1.50E-09 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| No/unknown | ||||

| Yes | 0.59 (0.53-0.66) | 1.42E-21 | 1.39 (1.25-1.56) | 2.40E-09 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| No/unknown | ||||

| Yes | 0.71 (0.61-0.83) | 1.40E-05 | 1.25 (1.09-1.42) | 9.00E-04 |

| Lung metastasis | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 1.36 (1.22-1.52) | 9.97E-08 | 1.29 (1.15-1.45) | 1.60E-05 |

| Bone metastasis | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 1.22 (1.07-1.39) | 3.76E-03 | 1.24 (1.08-1.41) | 1.70E-03 |

| Brain metastasis | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 0.97 (0.65-1.44) | 0.89 | 0.96 (0.61-1.5) | 0.85 |

Actual OS and CSS rates since initial diagnosis and their corresponding CS are presented in Supplemen

According to d of conditional OS, risk factors could be categorized into three groups (Table 3): (1) |d| > 0.1, which means risk factors remained to be significant over time [AFP expression (negative vs positive), tumor size (> 5 cm vs ≤ 5 cm), T stage (T3 vs T1, T4 vs T1), N stage (N1 vs N0), and primary-site surgery (Yes vs No)]; (2) |d| > 0.1 → |d| < 0.1, which means the influence caused by risk factors gradually decreased [race (other race vs black race), chemotherapy (Yes vs No/unknown), and radiotherapy (Yes vs No/unknown)]; and (3) d < -0.1 → d > 0.1, which means the difference in survival caused by risk factors reversed over time [lung metastasis (Yes vs No)]. As for conditional CSS, risk factors could be also divided into three groups according to d value (Table 4): (1) |d| > 0.1, which means risk factors remained to be significant over time [AFP expression (negative vs positive), tumor size (> 5 cm vs ≤ 5 cm), T stage (T3 vs T1, T4 vs T1), N stage (N1 vs N0), and primary-site surgery (Yes vs No)]; (2) |d| > 0.1 → |d| < 0.1, which means the influence caused by risk factors gradually decreased [race (other race vs black race), chemotherapy (Yes vs No/unknown), and radiotherapy (Yes vs No/unknown)]; and (3) d < -0.1 → d > 0.1, which means the difference in survival caused by risk factors reversed over time [lung metastasis (Yes vs No)]. In addition, differences in conditional OS and CSS caused by age (55-65 vs < 55, ≥ 65 vs < 55) and gender (male vs female) gradually appeared over time (|d| < 0.1 → |d| > 0.1).

| Characteristics | Overall survival (months after diagnosis) | ||||||||

| 0 | d | 2 | d | 4 | d | 6 | d | ||

| Overall | 32.79 | 41.05 | 47.48 | 53.31 | |||||

| Age, yr | |||||||||

| < 55 | 30.69 | 42.39 | 59.26 | 64.45 | |||||

| 55-65 | 33.86 | 0.07 | 39.96 | -0.05 | 44.03 | -0.30 | 45.78 | -0.37 | |

| ≥ 65 | 32.64 | 0.04 | 41.65 | -0.02 | 49.58 | -0.19 | 56.99 | -0.15 | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 34.64 | 43.92 | 52.4 | 55.63 | |||||

| Male | 32.38 | -0.05 | 40.42 | -0.07 | 46.37 | -0.12 | 52.75 | -0.06 | |

| Race | |||||||||

| Black | 33.03 | 41.07 | 48.04 | 51.95 | |||||

| White | 34.35 | 0.03 | 42.77 | 0.03 | 48.1 | 0.001 | 54.56 | 0.05 | |

| Other | 27.17 | -0.12 | 34.55 | -0.13 | 44.34 | -0.07 | 49.06 | -0.06 | |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married | 32.59 | 40.58 | 46.51 | 54.99 | |||||

| Single | 32.99 | 0.01 | 42.24 | 0.03 | 51.3 | 0.10 | 52.08 | -0.06 | |

| Separated | 32.96 | 0.01 | 40.71 | 0.00 | 45.57 | -0.02 | 51.27 | -0.07 | |

| AFP expression | |||||||||

| Positive | 30.77 | 38.99 | 44.09 | 49.63 | |||||

| Negative | 43.69 | 0.28 | 50.46 | 0.23 | 62.1 | 0.36 | 67.32 | 0.35 | |

| Tumor size | |||||||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 38.43 | 50.31 | 62.75 | 60.63 | |||||

| > 5 cm | 30.67 | -0.17 | 37.48 | -0.26 | 39.59 | -0.46 | 49.85 | -0.22 | |

| T stage | |||||||||

| T1 | 39.82 | 49.18 | 56.84 | 60.72 | |||||

| T2 | 36.94 | -0.06 | 49.78 | 0.01 | 57 | 0.003 | 55.68 | -0.10 | |

| T3 | 28.86 | -0.23 | 34.84 | -0.29 | 41.77 | -0.30 | 49.69 | -0.22 | |

| T4 | 31.63 | -0.17 | 40.2 | -0.18 | 33.72 | -0.46 | 46.16 | -0.29 | |

| N stage | |||||||||

| N0 | 34.58 | 43.29 | 50.08 | 57.11 | |||||

| N1 | 28.87 | -0.12 | 35.65 | -0.16 | 40.76 | -0.19 | 43.26 | -0.28 | |

| Surgery | |||||||||

| No | 30.65 | 38.31 | 44.61 | 50.83 | |||||

| Yes | 69.51 | 0.83 | 73.97 | 0.73 | 74.6 | 0.60 | 71.93 | 0.42 | |

| Chemotherapy | |||||||||

| No/unknown | 21.54 | 35.16 | 46.49 | 52.55 | |||||

| Yes | 42.34 | 0.44 | 44.13 | 0.18 | 47.92 | 0.03 | 53.61 | 0.02 | |

| Radiotherapy | |||||||||

| No/unknown | 28.85 | 38.14 | 45.8 | 53 | |||||

| Yes | 48.42 | 0.42 | 49.72 | 0.24 | 50 | 0.08 | 54.05 | 0.02 | |

| Lung metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 38.7 | 44.51 | 48.12 | 51.58 | |||||

| Yes | 22.59 | -0.34 | 33.02 | -0.23 | 45.71 | -0.05 | 58.48 | 0.14 | |

| Bone metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 31.33 | 39.55 | 46.72 | 53.91 | |||||

| Yes | 36.41 | 0.11 | 44.54 | 0.10 | 49.19 | 0.05 | 51.94 | -0.04 | |

| Brain metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 32.85 | 41.08 | 47.44 | 53.15 | |||||

| Yes | 29.63 | -0.07 | 38.89 | -0.04 | 50 | 0.05 | 62.5 | 0.19 | |

| Characteristics | Cancer-specific survival (months after diagnosis) | ||||||||

| 0 | d | 2 | d | 4 | d | 6 | d | ||

| Overall | 34.77 | 42.48 | 48.6 | 55.11 | |||||

| Age, yr | |||||||||

| < 55 | 32.05 | 43.36 | 53.19 | 66.41 | |||||

| 55-65 | 36 | 0.08 | 41.63 | -0.04 | 45.44 | -0.16 | 42.52 | -0.48 | |

| ≥ 65 | 34.79 | 0.06 | 43.05 | -0.01 | 50.09 | -0.06 | 56.97 | -0.19 | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 36.67 | 45.76 | 54.64 | 58.38 | |||||

| Male | 34.35 | -0.05 | 41.77 | -0.08 | 47.24 | -0.15 | 54.33 | -0.08 | |

| Race | |||||||||

| Black | 36.22 | 43.24 | 49.22 | 55.84 | |||||

| White | 36.31 | 0.00 | 44.26 | 0.02 | 49.36 | 0.00 | 56.34 | 0.01 | |

| Other | 28.31 | -0.17 | 35.2 | -0.16 | 44.84 | -0.09 | 50.3 | -0.11 | |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married | 34.01 | 41.82 | 47.37 | 55.74 | |||||

| Single | 35.15 | 0.02 | 43.06 | 0.03 | 52.07 | 0.09 | 54.74 | -0.02 | |

| Separated | 36 | 0.04 | 43.25 | 0.03 | 47.46 | 0.00 | 54.23 | -0.03 | |

| AFP expression | |||||||||

| Positive | 32.75 | 44.94 | 45.3 | 51.21 | |||||

| Negative | 45.67 | 0.27 | 51.74 | 0.14 | 62.82 | 0.35 | 70 | 0.38 | |

| Tumor size | |||||||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 40.79 | 51.88 | 64.07 | 62.94 | |||||

| > 5 cm | 32.51 | -0.17 | 38.86 | -0.26 | 42.46 | -0.43 | 51.42 | -0.23 | |

| T stage | |||||||||

| T1 | 41.66 | 50.32 | 57.88 | 62.8 | |||||

| T2 | 40.4 | -0.03 | 51.47 | 0.02 | 59.43 | 0.03 | 57.77 | -0.10 | |

| T3 | 30.68 | -0.23 | 36.49 | -0.28 | 42.85 | -0.30 | 51.69 | -0.22 | |

| T4 | 32.82 | -0.19 | 40.66 | -0.20 | 38.16 | -0.39 | 46.15 | -0.33 | |

| N stage | |||||||||

| N0 | 36.48 | 44.7 | 51.36 | 62.39 | |||||

| N1 | 31.00 | -0.12 | 37.11 | -0.15 | 41.57 | -0.20 | 44.53 | -0.36 | |

| Surgery | |||||||||

| No | 32.69 | 39.81 | 45.84 | 52.64 | |||||

| Yes | 69.51 | 0.77 | 73.97 | 0.69 | 74.6 | 0.58 | 73.6 | 0.42 | |

| Chemotherapy | |||||||||

| No/unknown | 24.05 | 37.52 | 48.05 | 56.21 | |||||

| Yes | 43.68 | 0.41 | 45.05 | 0.15 | 48.87 | 0.02 | 54.64 | -0.03 | |

| Radiotherapy | |||||||||

| No/unknown | 30.92 | 39.7 | 47.66 | 55.55 | |||||

| Yes | 49.75 | 0.40 | 50.72 | 0.22 | 51 | 0.07 | 54.05 | -0.03 | |

| Lung metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 40.69 | 46.02 | 49.33 | 53.7 | |||||

| Yes | 24.4 | -0.34 | 34.24 | -0.24 | 46.61 | -0.05 | 59.18 | 0.11 | |

| Bone metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 33.52 | 41.03 | 48.1 | 55.99 | |||||

| Yes | 37.84 | 0.09 | 45.87 | 0.10 | 49.79 | 0.03 | 53.21 | -0.06 | |

| Brain metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 34.83 | 42.5 | 48.59 | 54.78 | |||||

| Yes | 31.91 | -0.06 | 42.48 | -0.0004 | 48.61 | 0.0004 | 64.46 | 0.19 | |

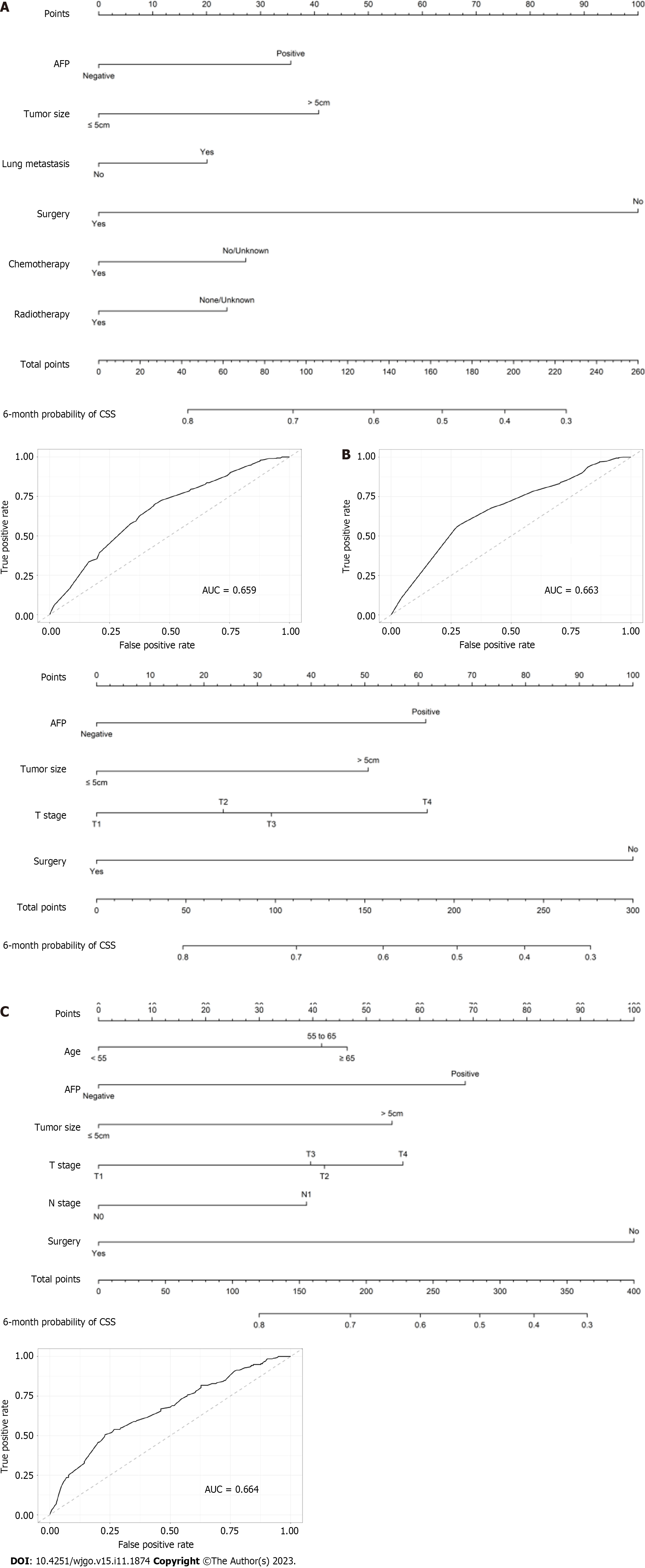

Prognostic relevance of features varied at different time since the initial diagnosis. Based on multivariate Cox regression model at different time points, three nomograms for 6-month conditional OS were fitted for patients who have lived for 2, 4 or 6 mo (Supplementary Table 4 and Figure 3). AUC for these nomograms gradually decreased over time: AUC was 0.679 for patients who survived 2 mo (Figure 3A); 0.663 for patients who survived 4 mo (Figure 3B); and 0.655 for patients who survived 6 mo (Figure 3C). The characteristics included in the nomogram changed with time, and AFP expression, tumor size, and primary-site surgery were prognostic indicators for all the three models.

Similarly, based on competing risk models at different time points, three nomograms for 6-month conditional CSS were conducted for patients who have lived for 2- 4 or 6 mo (Supplementary Table 5 and Figure 4). The value of AUC of the ROC curves gradually increased over time, and the AUCs for patients who survived 2, 4 and 6-mo were 0.659, 0.663 and 0.664, respectively (Figures 4A–C). AFP expression, tumor size, and primary-site surgery were still prognostic indicators that were included in all the models, while T stage was associated with 6-month conditional CSS for patients who lived for 2 or 4 mo.

As one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide, HCC is usually diagnosed at late and advanced stages[24]. While previous studies have concentrated on predicting prognosis for HCC patients, only a few have focused on distant metastatic HCC patients. Former studies on the prognosis of metastatic HCC have identified risk factors including older age, male gender, high T stage, low degree of tumor differentiation, N1 stage, non-primary site surgery, no chemoradiotherapy, larger tumor size, no radiotherapy, and multi-organ metastasis, while high T stage, N1 stage, non-primary site surgery, no chemotherapy, and no radiotherapy were also independent risk factors in our study[25,26].

Attributing to the characteristics of poor prognosis and high mortality rate, the predictive model that was constructed at the time of initial diagnosis would be influenced by patients who died in the first few months. Actual survival did not reflect how prognosis changed over time. Therefore, CS would provide patients with survival probabilities at a specific time since prognosis was adjusted for the time the patient had already survived[27]. There were several reports regarding CS of HCC, including a study that also used the data from SEER[22]. As reported in this study, the conditional OS improved from 8.4% to 44.1% for the AJCC stage IVB group during the first 5 years after initial diagnosis, and the conditional CSS improved from 12.1% to 66.7% in the AJCC stage IVB group. However, only 3.1% of distant metastatic HCC patients achieved a 5-year survival[28]. Thus, a 5-year CS could not reflect the survival situation for distant metastatic HCC patients and these patients should be separated from patients with early-stage HCC. Since 1 year survival rate was 17.48% for distant metastatic HCC patients in this study, we adopted a 6-month CS analysis, which was more suitable.

Compared with actual survival, which demonstrated a downward trend, conditional OS and CSS demonstrated upward trends over time. Survival rate for patients who had already lived for 6 mo to survive an additional 6 mo was 53.31%, while 12-month OS rate of the whole cohort was only 17.48% calculated at initial diagnosis. In subgroup analysis, risk factors of positive AFP expression, tumor size (> 5 cm), T stage (T3 and T4), N1 stage, and non-primary-site surgery maintained a substantial and stable effect on CS, while survival differences among races, chemotherapy groups, and radiotherapy groups decreased over time. Disparities in detection and treatment were linked to survival differences among ethnic groups, but their impact diminished over time[29]. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy were considered to be protective factors for survival at initial diagnosis, and they may provide benefit in the first few months. However, as time goes by, their influence decreases gradually. This may be due to the difference in molecular pathology and resistance that appeared 10 mo following the initial diagnosis. Also, patients who had a poorer condition could not tolerate chemo

Nomograms are useful tools combining tumor-related risk factors to estimate and predict the survival rate of different patients[36]. We constructed nomograms for 6-month CS at 2, 4 and 6 mo after initial diagnosis. These nomograms may help to predict dynamic survival for distant metastatic HCC survivors with greater accuracy. As risk indicators for survival kept changing as time passed, the features fitted in the nomograms also changed. AFP expression, tumor size, and primary-site surgery were included in all the nomograms, which was consistent with previous nomogram studies on HCC[37,38]. The value of AUC gradually decreased in nomograms for conditional OS, while the value of AUC showed a gradual and slight increase in models for conditional CSS. This may be explained by the fact that as time passes, the increased death rate for other causes led to a diminished effect of these clinicopathological factors on OS, but they kept their influence on CSS. These nomograms may help assess patients’ survival rates at different times. They can be used to remind clinicians and family members that more continued surveillance and care should be given to patients with lower CS rates. Furthermore, if patients have survived for a certain number of months, they may have a better prognosis, and the therapeutic goals and strategies can be more positive for them.

There were several limitations to our study. First, the research was a retrospective analysis with higher selection biases. Second, there was a lack of important features such as liver function, carcinoembryonic antigen, and vascular invasion that were not available in the SEER database, especially liver function, which was significant in the survival of HCC patients. Due to incomplete data, grade and fibrosis score were also not included in the analysis, which limited the ability of the nomogram to assess relevant survival. Third, the SEER database provided disease information at initial diagnosis, and so the metastasis events that occurred in the later survival time could not be recorded. We used data on HCC patients who were diagnosed from 2010 to 2015, and the treatment may have improved in the years since; for example, the occurrence of combination therapy, which includes immunotherapy and molecular targeted therapy, limited the use of our CS nomograms on these patients. For example, as the first small oral molecular targeted medicine, sorafenib successfully prolonged the OS of advanced HCC patients, and the novel programmed cell death 1 checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab could be used for patients who have disease progression or unacceptable adverse effects with sorafenib[39,40]. These are important factors that should be taken into consideration in the predictive model. We used the 7th edition of the AJCC staging system for HCC as the most up-to-date AJCC staging system for these patients was inaccessible. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer classifications for HCC was also not present in our study. Finally, although the constructed nomograms were internally validated, they also need external validation.

Positive AFP expression, higher T stage (T3 and T4), N1 stage, non-primary-site surgery, non-chemotherapy, non-radiotherapy, and lung metastasis were independent risk factors for actual OS and CSS through univariate and multivariate analysis. Actual survival rates decreased over time, while CS rates gradually increased. With dynamic risk factors, nomograms constructed at different time would provide more accurate CS.

Distant metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients have poor survival rates, while some of them who have survived for several months may have a better prognosis than the prediction at initial diagnosis. Conditional survival (CS) could provide patients with survival probabilities at a specific time since the prognosis would be adjusted for the time the patient had already survived.

In this study, we evaluated actual survival and CS of distant metastatic HCC patients.

This study aimed to evaluate the CS of distant metastatic HCC patients and construct nomograms to predict CS at different times.

We used Cox regression analysis to identify risk factors for overall survival (OS) and the competing risk model to identify risk factors for cancer-specific survival (CSS). Six-month CS was used to calculate the probability of survival for an additional 6 mo at a specific time after the initial diagnosis. We used standardized differences to evaluate the survival differences between subgroups. Nomograms were constructed to predict CS.

Using univariate and multivariate analysis, we found positive α-fetoprotein expression, higher T stage (T3 and T4), N1 stage, non-primary site surgery, non-chemotherapy, non-radiotherapy, and lung metastasis to be independent risk factors for actual OS and CSS. We found that actual survival rates decreased over time, while CS rates gradually increased. The influence of chemotherapy and radiotherapy on survival gradually disappeared over time; the influence of age and gender on survival gradually appeared; and the influence of lung metastasis reversed. The area under the curve (AUC) of nomograms for conditional OS decreased as time passed, and the AUC for conditional CSS gradually increased.

Actual survival rates decreased over time, while CS rates gradually increased. With dynamic risk factors, nomograms constructed at different time would provide more accurate CS.

CS could be used to evaluate the dynamic survival rates for distant metastatic HCC patients.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tchilikidi KY, Russia; Zimmitti G, Italy S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Zhang XD

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64628] [Article Influence: 16157.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (176)] |

| 2. | Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Altekruse SF, Ward JW, Jemal A, Sherman RL, Henley SJ, Holtzman D, Lake A, Noone AM, Anderson RN, Ma J, Ly KN, Cronin KA, Penberthy L, Kohler BA. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2012, featuring the increasing incidence of liver cancer. Cancer. 2016;122:1312-1337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 633] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 77.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Villanueva A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1450-1462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2066] [Cited by in RCA: 3173] [Article Influence: 528.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 4. | Katyal S, Oliver JH 3rd, Peterson MS, Ferris JV, Carr BS, Baron RL. Extrahepatic metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiology. 2000;216:698-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Shuto T, Hirohashi K, Kubo S, Tanaka H, Yamamoto T, Higaki I, Takemura S, Kinoshita H. Treatment of adrenal metastases after hepatic resection of a hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2001;18:294-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Elmoghazy W, Ahmed K, Vijay A, Kamel Y, Elaffandi A, El-Ansari W, Kakil R, Khalaf H. Hepatocellular carcinoma in a rapidly growing community: Epidemiology, clinico-pathology and predictors of extrahepatic metastasis. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2019;20:38-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yan B, Bai DS, Zhang C, Qian JJ, Jin SJ, Jiang GQ. Characteristics and risk differences of different tumor sizes on distant metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective cohort study in the SEER database. Int J Surg. 2020;80:94-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1485-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1196] [Cited by in RCA: 1326] [Article Influence: 82.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:589-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2184] [Cited by in RCA: 2902] [Article Influence: 483.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (17)] |

| 10. | Yang JD, Heimbach JK. New advances in the diagnosis and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. BMJ. 2020;371:544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz JF, Borbath I, Häussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J; SHARP Investigators Study Group. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9016] [Cited by in RCA: 10268] [Article Influence: 604.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Xu DZ, Hernandez S, Liu J, Huang C, Mulla S, Wang Y, Lim HY, Zhu AX, Cheng AL; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894-1905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2542] [Cited by in RCA: 4695] [Article Influence: 939.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5593] [Cited by in RCA: 6059] [Article Influence: 865.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 14. | Merrill RM, Hunter BD. Conditional survival among cancer patients in the United States. Oncologist. 2010;15:873-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Xiao M, Zhang P. Conditional cause-specific survival after chemotherapy and local treatment for primary stage IV breast cancer: A population-based study. Front Oncol. 2022;12:800813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | McNamara MG, Lwin Z, Jiang H, Chung C, Millar BA, Sahgal A, Laperriere N, Mason WP. Conditional probability of survival and post-progression survival in patients with glioblastoma in the temozolomide treatment era. J Neurooncol. 2014;117:153-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yoo JE, Han K, Shin DW, Park SH, Cho IY, Yoon DW, Cho J, Jung KW. Conditional relative survival and competing mortality in patients who underwent surgery for lung cancer: A nationwide cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:626-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nathan H, de Jong MC, Pulitano C, Ribero D, Strub J, Mentha G, Gigot JF, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Aldrighetti L, Capussotti L, Pawlik TM. Conditional survival after surgical resection of colorectal liver metastasis: an international multi-institutional analysis of 949 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:755-764, 764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Han L, Dai W, Mo S, Xiang W, Li Q, Xu Y, Cai G, Wang R. Nomogram of conditional survival probability of long-term Survival for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Real-World Data Retrospective Cohort Study from SEER database. Int J Surg. 2021;92:106013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang G, Li R, Deng Y, Zhao L. Conditional survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12:515-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee JS, Cho IR, Lee HW, Jeon MY, Lim TS, Baatarkhuu O, Kim DY, Han KH, Park JY. Conditional Survival Estimates Improve Over Time for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Analysis for Nationwide Korea Cancer Registry Database. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51:1347-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shah MM, Meyer BI, Rhee K, NeMoyer RE, Lin Y, Tzeng CD, Jabbour SK, Kennedy TJ, Nosher JL, Kooby DA, Maithel SK, Carpizo DR. Conditional survival analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cucchetti A, Piscaglia F, Cescon M, Ercolani G, Terzi E, Bolondi L, Zanello M, Pinna AD. Conditional survival after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4397-4405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang X, Zhang A, Sun H. Power of metabolomics in diagnosis and biomarker discovery of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;57:2072-2077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhan H, Zhao X, Lu Z, Yao Y, Zhang X. Correlation and Survival Analysis of Distant Metastasis Site and Prognosis in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:652768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chen L, Sun T, Chen S, Ren Y, Yang F, Zheng C. The efficacy of surgery in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a cohort study. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18:119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hieke S, Kleber M, König C, Engelhardt M, Schumacher M. Conditional Survival: A Useful Concept to Provide Information on How Prognosis Evolves over Time. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1530-1536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, Makuuchi M, Izumi N, Ichida T, Kudo M, Ku Y, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, Matsui O, Matsuyama Y. Comparison of resection and ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a cohort study based on a Japanese nationwide survey. J Hepatol. 2013;58:724-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rich NE, Hester C, Odewole M, Murphy CC, Parikh ND, Marrero JA, Yopp AC, Singal AG. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Presentation and Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:551-559.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | De Maria N, Manno M, Villa E. Sex hormones and liver cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;193:59-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kalra M, Mayes J, Assefa S, Kaul AK, Kaul R. Role of sex steroid receptors in pathobiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5945-5961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Manieri E, Herrera-Melle L, Mora A, Tomás-Loba A, Leiva-Vega L, Fernández DI, Rodríguez E, Morán L, Hernández-Cosido L, Torres JL, Seoane LM, Cubero FJ, Marcos M, Sabio G. Adiponectin accounts for gender differences in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence. J Exp Med. 2019;216:1108-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Makarova-Rusher OV, Altekruse SF, McNeel TS, Ulahannan S, Duffy AG, Graubard BI, Greten TF, McGlynn KA. Population attributable fractions of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 2016;122:1757-1765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rich NE, Murphy CC, Yopp AC, Tiro J, Marrero JA, Singal AG. Sex disparities in presentation and prognosis of 1110 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:701-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Chen L, Wang Z, Song S, Sun T, Ren Y, Zhang W, Wang M, Liu Y, Zheng C. The Efficacy of Radiotherapy in the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Distant Organ Metastasis. J Oncol. 2021;2021:5190611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Balachandran VP, Gonen M, Smith JJ, DeMatteo RP. Nomograms in oncology: more than meets the eye. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e173-e180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1119] [Cited by in RCA: 2396] [Article Influence: 239.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Liu K, Huang G, Chang P, Zhang W, Li T, Dai Z, Lv Y. Construction and validation of a nomogram for predicting cancer-specific survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10:21376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Yan B, Su BB, Bai DS, Qian JJ, Zhang C, Jin SJ, Jiang GQ. A practical nomogram and risk stratification system predicting the cancer-specific survival for patients with early hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2021;10:496-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Liu Z, Lin Y, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Li Y, Liu Z, Li Q, Luo M, Liang R, Ye J. Molecular targeted and immune checkpoint therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Peng TR, Wu CC, Chang SY, Chen YC, Wu TW, Hsu CS. Therapeutic efficacy of nivolumab plus sorafenib therapy in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;112:109223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |