Published online Sep 15, 2022. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v14.i9.1823

Peer-review started: April 19, 2022

First decision: May 11, 2022

Revised: May 14, 2022

Accepted: August 14, 2022

Article in press: August 14, 2022

Published online: September 15, 2022

Processing time: 143 Days and 2.4 Hours

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been widely used in the treatment of early gastric cancer (EGC). A personalized and effective prediction method for ESD with EGC is urgently needed.

To construct a risk prediction model for ulcers after ESD for EGC based on LASSO regression.

A total of 196 patients with EGC who received ESD treatment were prospectively selected as the research subjects and followed up for one month. They were divided into an ulcer group and a non-ulcer group according to whether ulcers occurred. The general data, pathology, and endoscopic characteristics of the groups were compared, and the best risk predictor subsets were screened by LASSO regression and tenfold cross-validation. Multivariate logistic regression was applied to analyze the risk factors for ulcers after ESD in patients with EGC. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to estimate the predic

One month after the operation, no patient was lost to follow-up. The incidence of ulcers was 20.41% (40/196) (ulcer group), and the incidence of no ulcers was 79.59% (156/196) (non-ulcer group). There were statistically significant differences in the course of disease, Helicobacter pylori infection history, smoking history, tumor number, clopidogrel medication history, lesion diameter, infiltration depth, convergent folds, and mucosal discoloration between the groups. Gray's medication history, lesion diameter, convergent folds, and mucosal discoloration, which were the 4 nonzero regression coefficients, were screened by LASSO regression analysis. Further multivariate logistic analysis showed that lesion diameter [Odds ratios (OR) = 30.490, 95%CI: 8.584-108.294], convergent folds (OR = 3.860, 95%CI: 1.060-14.055), mucosal discoloration (OR = 3.191, 95%CI: 1.016-10.021), and history of clopidogrel (OR = 3.554, 95%CI: 1.009-12.515) were independent risk factors for ulcers after ESD in patients with EGC (P < 0.05). The ROC curve showed that the area under the curve of the risk prediction model for ulcers after ESD in patients with EGC was 0.944 (95%CI: 0.902-0.972).

Clopidogrel medication history, lesion diameter, convergent folds, and mucosal discoloration can predict the occurrence of ulcers after ESD in patients with EGC.

Core Tip: In recent years, with the development of endoscopic techniques, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been widely used in the treatment of early gastric cancer (EGC). Nevertheless, it is difficult to determine the presence of histological ulcers before ESD, and the presence of ulcers in EGCs is closely related to their depth of invasion and lymphatic invasion. In this study, we aimed to build a personalized prediction model for EGC patients after ESD.

- Citation: Gong SD, Li H, Xie YB, Wang XH. Construction and analysis of an ulcer risk prediction model after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2022; 14(9): 1823-1832

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v14/i9/1823.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v14.i9.1823

Gastric cancer is a common, widespread cancer. According to the "2020 Latest Global Cancer Burden" released by the World Health Organization, there were 1.089 million new gastric cancer cases and 768000 deaths worldwide, of which 478000 new cases and 373000 deaths were in China, accounting for nearly half of the cases, equivalent to 1022 Chinese people dying every day due to gastric cancer[1]. The prognosis of early gastric cancer is significantly better than that of advanced gastric cancer due to the low rate of lymphatic metastasis and distant metastasis[2].

In recent years, with the development of endoscopic techniques, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been widely used in the treatment of early gastric cancer (EGC)[3,4]. Compared to previous treatments, the scope of ESD treatment is expanded, the resection rate is improved, the residual lesion is reduced, the recurrence rate is reduced, and the cure rate of digestive tract lesions is improved[5]. Therefore, ESD is currently the main endoscopic resection treatment for early gastric cancer; however, due to the wide range of ESD peeling, deep lesion peeling, difficult operations, and relatively high risk of complications such as bleeding and perforation[6-8], personalized and effective methods to predict the outcome are urgently needed in clinical practice.

The Japanese Gastric Cancer Association proposed that the absolute indications for ESD for EGC radical resection initially included non-ulcerative, well-differentiated mucosal lesions ≤ 2 cm in diameter. However, the absolute indications are so strict that unnecessary surgery may be performed. Subsequently, after a rigorous investigation of surgical specimens, the indications for ESD were expanded to include a larger diameter, undifferentiated mucosal lesions, and differentiated lesions with mild submucosal infiltration[9,10].

A recent meta-analysis showed that the postoperative ulcer risk was relatively low in patients who met the absolute indications, suggesting that if radical endoscopic dissection is accurately predicted based on histopathology, it may be possible to avoid intraoperative specimen excision[11]. Nevertheless, it is difficult to determine the presence of histological ulcers before ESD, and the presence of ulcers in EGCs is closely related to their depth of invasion and lymphatic invasion. Ruptures are considered ulcers, which undoubtedly overestimate the disease and lead to unnecessary surgery[12,13]. In addition, an endoscopy study reported that EGC ulcers might heal spontaneously without mucosal rupture. The presence of an ulcer is critical in deciding on the treatment modality[14].

In our study, LASSO regression was performed to screen the factors influencing the risk of ulcers in EGC patients after ESD. Based on the differential indicators, we aimed to build a personalized prediction model that may provide a theoretical basis for the prevention of ulcers in EGC patients after ESD.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital. After signed informed consent was obtained, 196 EGC patients who received ESD treatment in our hospital from March 2019 to March 2021 were enrolled in our study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Met the diagnostic criteria for early gastric cancer confirmed by pathological examination; (2) the depth of invasion was limited to the mucosa and submucosa without lymph node metastasis; and (3) all patients provided informed consent and signed the consent form. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) gastric cancer combined with tumors in other parts; (2) epithelial tumor, adenocarcinoma or gastric adenoma; and (3) received radiotherapy, chemotherapy and/or surgery before ESD[15]. The occurrence of postoperative ulcers was evaluated 1 mo after ESD. At the same time, according to previous literature reports and clinical references, the baseline data and endoscopic characteristics of patients before ESD treatment were collected, and the factors influencing postoperative ulcers were discussed. A risk prediction model for ulcers after ESD in patients with early gastric cancer was constructed, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were drawn to verify the effectiveness of the prediction model.

General intravenous anesthesia was performed on all patients during ESD in our study. The size and scope of the lesions were determined by endoscopy before surgery, and the depth of invasion of the lesions was determined to exclude the possibility of lymph node metastasis. The detailed scheme of EDS treatment was as follows: (1) Marking: the periphery of the lesion was marked by electrocoagulation at a distance of 5.0 mm from the outer edge of the lesion by subion coagulation; (2) submucosal injection: indigo rouge injection (Southwest Pharmaceuticals; batch no. H50021944; 10 mL: 40 mg) for multipoint submucosal injection to ensure that the lesion mucosa was uplifted; (3) circular incision: a needle knife was used to cut the outer edge of the lesion along the marked point of the lesion edge; (4) mucosal peeling: repeated submucosal injection and separation to strip and excise the lesion from the submucosa; (5) wound treatment: thermal biopsy forceps and titanium clips were used to treat the postoperative bleeding points and lesion edges; and (6) postoperative treatment: the size of the lesion was measured, it was fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution and sent for histopathology to clarify the nature of the lesion.

The data collection included the general information of the patients, their pathological features and the endoscopic features. The general information of the patients included age, sex (male/female), course of disease, body mass index [weight (kg)/height (m2)], history of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, family history of gastric cancer, lesion site, comorbid diseases (hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease), residence (rural, urban), smoking history, drinking history, and drug history (aspirin, clopidogrel). The pathological features included lesion diameter, pathological type (differentiated carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma), number of tumors (single, multiple), depth of invasion (submucosal, muscularis mucosa), and vascular invasion. The endoscopic features included the lesion site (upper 1/3 of the stomach, middle 1/3 of the stomach, lower 1/3 of the stomach), lesion surface (convex, flat, depressed), mucosal rupture (regardless of the depth of invasion, any mucosal defect represents the presence of mucosal ruptures), mucosal discoloration (discoloration of any part of the lesion or the entire lesion contrasts with that of the surrounding mucosa, indicating a color change), and converging folds (the presence of any centripetal folds in the lesion indicates converging folds).

Data quality control was performed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which were strictly implemented to ensure the authenticity of the patient data. Specialized personnel collected and checked the general data of the patients, and the data were double-entered in parallel into EpiData software to ensure accuracy.

Follow-up and observation were performed for one month. Endoscopic review within 1 mo after the operation, local anesthesia and gastroscopic observation of the patient's lesions were performed. Then, 500 mL of 400% degassed distilled water was injected into the stomach, and endoscopic examination was performed under immersion. The occurrence of ulcers after ESD in the patients was recorded. The criteria for ulceration were mucosal defects involving the submucosa, muscularis propria malformation, or fibrosis in the submucosa or deeper layers under endoscopy[16,17].

SPSS 22.0 statistical software was used in our study. The measurement data were first tested for normality; the normally distributed data are expressed as the mean ± SD, and two independent samples t-tests were used for comparisons between groups. Count data are given as n (%), and differences between groups were compared using the χ2 test. Based on R software (glmnet package), LASSO regression was performed, and the tenfold cross-validation method was used to screen the best risk predictor subset. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the odds ratio. ROC analysis was performed to evaluate the effectiveness of the prediction model. A Z score test was performed to compare the ROC curves of the different indicators. A P value less than 0.05 represents a significant difference.

One month after the operation, no cases were lost to follow-up, the incidence of ulcers was 20.41% (40/196) (ulcer group), and the incidence of no ulcers was 79.59% (156/196) (non-ulcer group). There was no significant difference in age, sex, body mass index, drinking history, family history of gastric cancer, number of tumors, comorbidities, residence, or aspirin medication history between the two groups (P > 0.05). There were significant differences in the course of disease (P = 0.032), history of H. pylori infection (P = 0.041), smoking history (P = 0.045), and proportion of clopidogrel medication history (P < 0.001) between the two groups (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

| General Information | Ulcer group (n = 40) | Non-ulcer group (n = 156) | t/χ2 value | P value |

| Sex | 0.83 | 0.362 | ||

| Male | 26 (65.00) | 89 (57.05) | ||

| Female | 14 (35.00) | 67 (42.95) | ||

| Age | 48.98 ± 8.23 | 47.11 ± 9.02 | 1.257 | 0.213 |

| BMI | 22.25 ± 2.01 | 21.83 ± 1.98 | 1.183 | 0.242 |

| Course of disease (yr) | 2.85 ± 0.48 | 2.66 ± 0.52 | 2.195 | 0.032 |

| History of H. pylori infection | 7 (17.50) | 11 (7.05) | 4.168 | 0.041 |

| Family history of GC | 8 (20.00) | 22 (14.10) | 0.854 | 0.355 |

| Drinking history | 9 (22.50) | 26 (16.67) | 0.739 | 0.39 |

| Smoking history | 24 (60.00) | 66 (42.31) | 4.013 | 0.045 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 9 (22.50) | 26 (16.67) | 0.739 | 0.39 |

| Diabetes | 6 (15.00) | 22 (14.10) | 0.021 | 0.885 |

| Coronary heart disease | 7 (17.50) | 23 (14.75) | 0.187 | 0.666 |

| Residence | 0.116 | 0.733 | ||

| Rural | 25 (62.50) | 102 (65.38) | ||

| Town | 15 (37.50) | 54 (34.62) | ||

| Medication history | ||||

| Aspirin | 12 (30.00) | 28 (17.95) | 2.847 | 0.092 |

| Clopidogrel | 19 (47.50) | 27 (17.31) | 16.158 | < 0.001 |

The pathological features in the ulcer group (n = 40) and non-ulcer group (n = 156) were compared. There was no significant difference in pathological type or vascular invasion between the two groups (P > 0.05), but there were statistically significant differences in lesion diameter (P < 0.001), the number of tumors (P = 0.041), and infiltration depth (P = 0.046) between the two groups (Table 2).

| Pathological features | Ulcer group (n = 40) | Non-ulcer group (n = 156) | t/χ2 value | P value |

| Lesion diameter (cm) | 4.40 ± 0.97 | 2.97 ± 0.62 | 8.871 | < 0.001 |

| Number of tumors | 4.185 | 0.041 | ||

| Single shot | 18 (45.00) | 98 (62.83) | ||

| Multiple | 22 (55.00) | 58 (37.18) | ||

| Pathological type | 0.268 | 0.605 | ||

| Differentiated carcinoma | 19 (47.50) | 67 (42.95) | ||

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 21 (52.50) | 89 (57.05) | ||

| Infiltration depth | 3.988 | 0.046 | ||

| Submucosa | 21 (52.50) | 55 (35.26) | ||

| Mucosal layer | 19 (47.50) | 101 (64.74) | ||

| Vascular invasion | 2 (5.00) | 6 (3.85) | 0.108 | 0.742 |

The endoscopic features in the ulcer group (n = 40) and non-ulcer group (n = 156) were compared. There was no significant difference in lesion site or lesion surface between the two groups (P > 0.05), but there were statistically significant differences in mucosal discoloration (P < 0.001) and convergent folds (P < 0.001) between the two groups, as shown in Table 3.

| Endoscopic features | Ulcer group (n = 40) | Non-ulcer group (n = 156) | χ2 value | P value |

| Lesion site | 2.132 | 0.344 | ||

| Upper 1/3 of stomach | 12 (30.00) | 61 (39.10) | ||

| 1/3 of stomach | 20 (50.00) | 76 (48.72) | ||

| Lower 1/3 of stomach | 8 (20.00) | 19 (12.18) | ||

| Mucosal discoloration | 28 (70.00) | 63 (40.38) | 11.227 | < 0.001 |

| Convergence folds | 28 (60.00) | 49 (31.41) | 19.877 | < 0.001 |

| Lesion surface | 1.105 | 0.576 | ||

| Bulge | 11 (27.50) | 52 (33.33) | ||

| Flat | 15 (37.50) | 62 (39.74) | ||

| Sag | 14 (35.00) | 42 (26.93) |

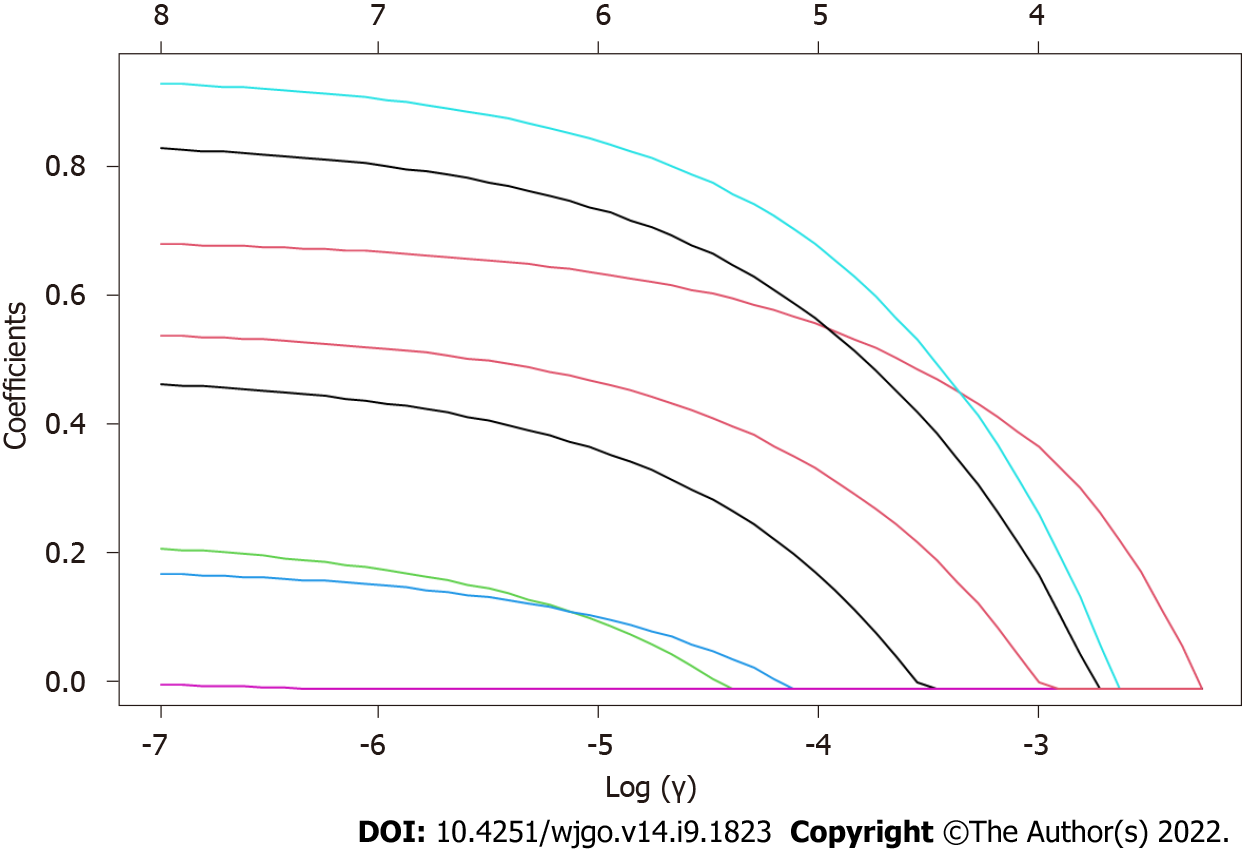

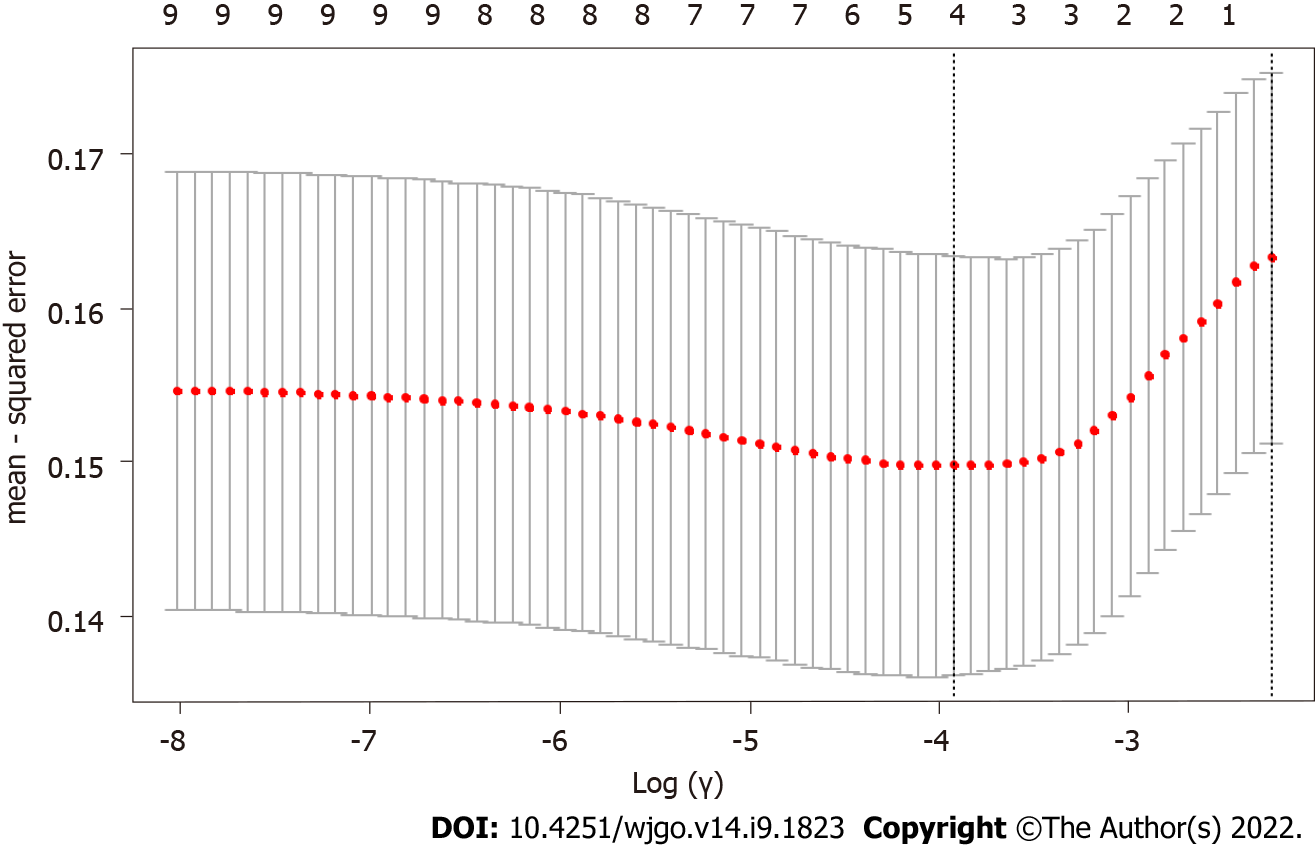

After the differential information of the patients, pathological features and endoscopic features was obtained, LASSO regression analysis was performed on the above independent variables (the course of disease, history of H. pylori infection, smoking history, clopidogrel medication history, lesion diameter, number of tumors, infiltration depth, mucosal discoloration, and convergent folds) (Figure 1). With the change in the penalty coefficient λ, the coefficients of the independent variables initially included in the model were gradually compressed, and finally, the coefficients of some independent variables were compressed to 0. Then, the 10-fold cross-validation method was used to validate the independent variables. After validation, clopidogrel medication history, lesion diameter, convergent folds, and mucosal discoloration were the 4 independent variables that predicted postoperative ulceration (Figure 2).

Taking the occurrence of ulcers as the dependent variable (ulcer occurrence = 1, no ulcer occurrence = 0), the above variables with statistically significant differences were used as independent variables for logistic regression analysis, and variable selection was performed by the stepwise method (α in = 0.05, α out = 0.1). Multivariate logistic analysis showed that lesion diameter [Odds ratios (OR)= 30.490, 95%CI: 8.584-108.294], convergent folds (OR = 3.860, 95%CI: 1.060-14.055), mucosal discoloration (OR = 3.191, 95%CI: 1.016-10.021) and clopidogrel medication history (OR = 3.554, 95%CI: 1.009-12.515) were independent risk factors for ulcers after ESD in EGC patients (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

| Related indicator | β | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Lesion diameter | 3.417 | 0.647 | 27.927 | < 0.001 | 30.490 | 8.584 | 108.294 |

| Clopidogrel medication history | 1.268 | 0.642 | 3.899 | 0.048 | 3.554 | 1.009 | 12.515 |

| Convergent folds | 1.351 | 0.659 | 4.195 | 0.041 | 3.860 | 1.060 | 14.055 |

| Mucosal discoloration | 1.160 | 0.584 | 3.950 | 0.047 | 3.191 | 1.016 | 10.021 |

ROC curve analysis showed that the area under the curve (AUC) of the risk prediction model for ulcers after ESD in patients with EGC was 0.916 (95%CI: 0.865-0.967). In addition, ROC curves of the lesion diameter, convergent folds, mucosal discoloration and clopidogrel medication history for ulcer occurrence after ESD in EGC patients were also evaluated. Among the four indicators alone, the AUC of the lesion diameter was the best, 0.885 (95%CI: 0.814-0.955), and the AUCs of convergent folds, mucosal discoloration and clopidogrel medication history were 0.651 (95%CI: 0.549-0.753), 0.648 (95%CI: 0.554-0.742) and 0.693 (95%CI: 0.601-0.785), respectively. Compared to the four indicators alone, the combined prediction model should significantly increase the accuracy of the prediction of ulcer occurrence after ESD in EGC patients (Table 5).

| Indicator | AUC | SD | P value | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Lesion diameter | 0.885 | 0.036 | < 0.001 | 0.814 | 0.955 |

| Clopidogrel medication history | 0.651 | 0.052 | 0.003 | 0.549 | 0.753 |

| Mucosal discoloration | 0.648 | 0.048 | 0.004 | 0.554 | 0.742 |

| Convergent folds | 0.693 | 0.047 | < 0.001 | 0.601 | 0.785 |

| Prediction model | 0.916 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.865 | 0.967 |

With advances in endoscopic techniques, ESD has become widely used in EGC treatment. ESD can provide a higher quality of life than surgical resection in terms of long-term outcomes[18]. To select ESD patients who may benefit from this treatment, personalized prediction of the outcome of EGC treatment is needed; therefore, previous studies have analyzed various clinicopathological factors and imaging modalities for personalized prediction[19]. Compared with non-ulcer EGCs, the incidence of lymph node micro-metastases in ulcerative EGC is significantly increased, so the presence or absence of ulcers has been identified as the key to a personalized treatment strategy for EGC.

However, currently, the presence of ulcers in the current ER criteria does not refer to endoscopic ulcers but to histological ulcers, which are based on data from surgically resected specimens. It is difficult to assess histological ulcers from biopsy specimens prior to treatment. Although the histological appearance of ulcers is considered to be an important factor in EGC treatment decisions and ESD curability, they should also be distinguished from biopsy-derived scars[20,21]. Mucosal rupture cannot be defined as an ulcer alone, but some clinicians believe that it could be described as an endoscopic ulcer, which may lead to overestimation of ulcerative EGC. To avoid unnecessary surgery, careful examination and personalized assessment of the ulcer under endoscopy is urgently needed in clinical practice[22].

In terms of endoscopic features, a previous study of endoscopic images of EGC patients showed that the diagnostic accuracy was 28.2% in the case of superficial mucosal ruptures without converging folds; in cases with confluent folds without mucosal ruptures and in patients with pathological ulcerative lesions, the diagnostic accuracy was only 35.9%[23]. The reason for this may be that most endoscopists tend to consider sunken lesions or lesions with mucosal ruptures as endoscopic ulcers. In another study[24], the lesion surface was irregular, and concentric folds of the diseased tissue were observed during the postoperative healing process of mixed EGC.

Converging folds of the EGC being a risk factor for ulceration was confirmed in our study. We believe that converging folds may originate from previous ulcers during the healing process, which indicates the presence of histological ulcers, and the presence of ulcer scars is negatively related to the effect of ESD. If converging folds are observed during endoscopy, it should be concluded that the lesion is accompanied by ulcer scars, and the probability of postoperative ulceration is high, so the procedure should be handled by a skilled endoscopist.

In addition, a recent study reported that white discoloration was associated with undifferentiated histology of EGC[25]. It was also shown that well-differentiated or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma tumors have abundant and dense blood vessels, while low-grade adenocarcinoma tumors have sparse and loose blood vessels[26]. These findings are associated with cancerous mucosal redness in well-differentiated or moderately differentiated adenocarcinomas and pallor in undifferentiated carcinomas. A retrospective study showed that a color change (OR = 2.33) was an independent factor for predicting histological ulcers[27]. These results were also confirmed in our study.

The relationship between clinicopathological features and postoperative ulceration is also a hot topic in various studies, and previous studies have confirmed that the diameter of the lesion is a predictor of ulceration after ESD[28], because the larger the tumor diameter is, the greater the resection range. The larger the size, the longer the treatment time, which was also observed in this study.

In addition, some studies identified antithrombotic therapy as an independent risk factor for ESD ulcers[29]. A history of clopidogrel use was associated with the occurrence of ulcers after ESD[30]. In our study, a history of clopidogrel medication was also an independent risk factor for ulcers after ESD in EGC patients. The reason may be that the long-term use of clopidogrel before surgery may lead to changes in the patients' coagulation function and increase the risk of postoperative ulcers. However, it is worth noting that aspirin and clopidogrel are both antithrombotic drugs, and aspirin does not increase the risk of postoperative ulcers, which may be related to the relatively small sample size of this study, so the relationship between aspirin and the risk of postoperative ulcers should be examined in a future study.

However, there are still some shortcomings in our study. First, our study was a single-center study, which may have selection bias in the collection of clinical case data. A multicenter study should be performed in the future. Second, the sample size was relatively small, and the predictive model of ulcers after ESD in EGC patients needs to be confirmed in a much larger study. Third, although a risk prediction model for EGC was built, the model was not validated. A prospective study should be performed to further confirm these results.

In summary, clopidogrel medication history, lesion diameter, convergent folds, and mucosal discoloration can predict the occurrence of ulcers after ESD in patients with EGC. The LASSO regression-based ulcer risk prediction model for EGC may be feasible and meaningful, and its clinical application value can effectively help clinicians identify high-risk groups for ulcers after ESD for EGC and provide targeted treatment measures.

With the development of endoscopic techniques, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been widely used in the treatment of early gastric cancer (EGC); however, due to the wide range of ESD peeling, deep lesion peeling, difficult operations, and relatively high risk of complications such as bleeding and perforation, a personal predictive model of the outcome is necessary.

A personalized and effective prediction method of the outcomes of ESD for EGC is urgently needed in clinical practice.

This study aimed to build a personalized prediction model that may provide a theoretical basis for the prevention of ulcers among EGC patients after ESD.

A total of 196 EGC patients who received ESD treatment in our hospital from March 2019 to March 2021 were enrolled in our study. The general information of the patients, pathological features and endoscopic features were analyzed, and multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate their predictive value.

After LASSO regression analysis and validation, clopidogrel medication history, lesion diameter, convergent folds, and mucosal discoloration were the 4 independent variables that predicted postoperative ulceration. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis showed that the AUC of the risk prediction model for ulcers after ESD in patients with EGC was 0.916 (95%CI 0.865-0.967). Compared to each of the four indicators alone, their combined prediction model should have significantly increased accuracy for the prediction of ulcer occurrence after ESD for EGC patients.

A LASSO regression-based ulcer risk prediction model that included clopidogrel medication history, lesion diameter, convergent folds, and mucosal discoloration was built for EGC.

A large sample size should be used to validate the prediction model in future studies.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Albillos A, Spain; McDowell HR, United Kingdom; Shroff RT, United States S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JL

| 1. | Jin G, Lv J, Yang M, Wang M, Zhu M, Wang T, Yan C, Yu C, Ding Y, Li G, Ren C, Ni J, Zhang R, Guo Y, Bian Z, Zheng Y, Zhang N, Jiang Y, Chen J, Wang Y, Xu D, Zheng H, Yang L, Chen Y, Walters R, Millwood IY, Dai J, Ma H, Chen K, Chen Z, Hu Z, Wei Q, Shen H, Li L. Genetic risk, incident gastric cancer, and healthy lifestyle: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies and prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1378-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Machlowska J, Baj J, Sitarz M, Maciejewski R, Sitarz R. Gastric Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Genomic Characteristics and Treatment Strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 897] [Cited by in RCA: 856] [Article Influence: 171.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shiotsuki K, Takizawa K, Ono H. Indications of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Undifferentiated Early Gastric Cancer: Current Status and Future Perspectives for Further Expansion. Digestion. 2022;103:76-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nishizawa T, Yahagi N. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection: technique and new directions. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33:315-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yanai Y, Yokoi C, Watanabe K, Akazawa N, Akiyama J. Endoscopic resection for gastrointestinal tumors (esophageal, gastric, colorectal tumors): Japanese standard and future prospects. Glob Health Med. 2021;3:365-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim GH, Jung HY. Endoscopic Resection of Gastric Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2021;31:563-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yu J, Zhang Y, Qian J. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in the treatment of patients with early colorectal carcinoma and precancerous lesions. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;11:911-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen Z, Dou L, Zhang Y, He S, Liu Y, Lei H, Wang G. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection for metachronous early cancer or precancerous lesions emerging at the anastomotic site after curative surgical resection of colorectal cancer. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:1411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M, Matsui T. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Uedo N, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Fujimoto K. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer (second edition). Dig Endosc. 2021;33:4-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 77.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zheng Z, Yin J, Li Z, Ye Y, Wei B, Wang X, Tian Y, Li M, Zhang Q, Zeng N, Xu R, Chen G, Zhang J, Li P, Cai J, Yao H, Zhang Z, Zhang S. Protocol for expanded indications of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer in China: a multicenter, ambispective, observational, open-cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shimozato A, Sasaki M, Ogasawara N, Funaki Y, Ebi M, Tamura Y, Izawa S, Hijikata Y, Yamaguchi Y, Kasugai K. Risk Factors for Delayed Ulcer Healing after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection of Gastric Neoplasms. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2017;26:363-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tao J, Wang Y. Antithrombotic drug use effect in the treatment of early gastric cancer by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2017;30:1157-1164. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ariyoshi R, Toyonaga T, Tanaka S, Abe H, Ohara Y, Kawara F, Ishida T, Morita Y, Umegaki E, Azuma T. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms extending to the cervical esophagus. Endoscopy. 2018;50:613-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cai MY, Zhu Y, Zhou PH. [Endoscopic minimally invasive treatment--from inside the lumen to outside the lumen, from the superficial layer to the deep layer]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2019;22:601-608. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Chen H, Li B, Li L, Vachaparambil CT, Lamm V, Chu Y, Xu M, Cai Q. Current Status of Endoscopic Resection of Gastric Subepithelial Tumors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:718-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Takizawa K, Ono H, Muto M. Current indications of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2019;49:797-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tao M, Zhou X, Hu M, Pan J. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for patients with early gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim JW, Lee H, Min YW, Min BH, Lee JH, Sohn TS, Kim JJ, Kim S. Oncologic Safety of Endoscopic Resection Based on Lymph Node Metastasis in Ulcerative Early Gastric Cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2019;29:1105-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mahmoud M, Holzwanger E, Wassef W. Gastric interventional endoscopy. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33:461-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dohi O, Hatta W, Gotoda T, Naito Y, Oyama T, Kawata N, Takahashi A, Oka S, Hoteya S, Nakagawa M, Hirano M, Esaki M, Matsuda M, Ohnita K, Shimoda R, Yoshida M, Takada J, Tanaka K, Yamada S, Tsuji T, Ito H, Aoyagi H, Shimosegawa T. Long-term outcomes after non-curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer according to hospital volumes in Japan: a multicenter propensity-matched analysis. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:4078-4088. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Barola S, Fayad L, Hill C, Magnuson T, Schweitzer M, Singh V, Chen YI, Ngamruengphong S, Khashab MA, Kalloo AN, Kumbhari V. Endoscopic Management of Recalcitrant Marginal Ulcers by Covering the Ulcer Bed. Obes Surg. 2018;28:2252-2260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Park SM, Kim BW, Kim JS, Kim YW, Kim GJ, Ryu SJ. Can Endoscopic Ulcerations in Early Gastric Cancer Be Clearly Defined before Endoscopic Resection? Clin Endosc. 2017;50:473-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shichijo S, Uedo N, Kanesaka T, Ohta T, Nakagawa K, Shimamoto Y, Ohmori M, Arao M, Iwatsubo T, Suzuki S, Matsuno K, Iwagami H, Inoue S, Matsuura N, Maekawa A, Nakahira H, Yamamoto S, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Fukui K, Ito Y, Narahara H, Ishiguro S, Iishi H. Long-term outcomes after endoscopic submucosal dissection for differentiated-type early gastric cancer that fulfilled expanded indication criteria: A prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:664-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cheng J, Xia J, Zhuang Q, Xu X, Wu X, Wan X, Wang J, Zhou H. A new exploration of white globe appearance (WGA) in ulcerative lesions. Z Gastroenterol. 2020;58:754-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ryu DG, Choi CW, Kang DH, Kim HW, Park SB, Kim SJ, Nam HS. Predictive factors to diagnosis undifferentiated early gastric cancer after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee J, Kim BW, Huh CW, Kim JS, Maeng LS. Endoscopic Factors that Can Predict Histological Ulcerations in Early Gastric Cancers. Clin Endosc. 2020;53:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Guo Z, Miao L, Chen L, Hao H, Xin Y. Efficacy of second-look endoscopy in preventing delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:3855-3862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kawasaki K, Nakamura S, Kurahara K, Nagasue T, Yanai S, Harada A, Yaita H, Fuchigami T, Matsumoto T. Continuing use of antithrombotic medications for patients with bleeding gastroduodenal ulcer requiring endoscopic hemostasis: a case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:948-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yang SC, Wu CK, Tai WC, Liang CM, Yao CC, Wu KL, Hsu CN, Chuah SK. Risks of adverse events for users of proton-pump inhibitors plus aspirin or clopidogrel in patients with aspirin-related ulcer bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:1828-1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |