Published online Oct 15, 2022. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v14.i10.1933

Peer-review started: May 21, 2022

First decision: July 13, 2022

Revised: July 23, 2022

Accepted: September 12, 2022

Article in press: September 12, 2022

Published online: October 15, 2022

Processing time: 145 Days and 20 Hours

As a proteoglycan, VCAN exists in the tumor microenvironment and regulates tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, but its role in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has not yet been elucidated.

To investigate the expression and potential mechanism of action of VCAN in HCC.

Based on The Cancer Genome Atlas Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma dataset, we explored the correlation between VCAN expression and clinical features, and analyzed the prognosis of patients with high and low VCAN expression. The potential mechanism of action of VCAN was explored by Gene Ontology analysis, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analysis, and gene set enrichment analysis. We also explored immune cell infiltration, immune checkpoint gene expression, and sensitivity of immune checkpoint [programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4)] inhibitor therapy in patients with different VCAN expression. VCAN mRNA expression and VCAN meth

VCAN was highly expressed in HCC tissues, which was associated with a poor prognosis in HCC patients. No significant difference was found in VCAN mRNA expression in blood between patients with HBV-related cirrhosis and those with HCC, but there was a significant difference in VCAN methylation between the two groups. The correlation between VCAN and infiltrations of several different tumor immune cell types (including B cells, CD8+ T cells, and eosinophils) was significantly different. VCAN was strongly related to immune checkpoint gene expression and tumor mutation burden, and could be a biomarker of sensitivity to immune checkpoint (PD1/CTLA4) inhibitors. In addition, VCAN mRNA expression was associated with hepatitis B e antigen, HBV DNA, white blood cells, platelets, cholesterol, and coagulation function.

High VCAN level could be a possible biomarker for poor prognosis of HCC, and its immunomodulatory mechanism in HCC warrants investigation.

Core Tip: VCAN expression is significantly higher in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tumor tissue than in adjacent tissue, and high VCAN level may be a possible biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of HCC. VCAN is associated with hepatitis B e antigen in hepatitis B virus infected patients. VCAN may play a role in HCC through the extracellular matrix signaling pathway and inflammatory immune response, and is a potential biomarker for immune checkpoint (programmed cell death protein 1/cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4) inhibitors.

- Citation: Wang MQ, Li YP, Xu M, Tian Y, Wu Y, Zhang X, Shi JJ, Dang SS, Jia XL. VCAN, expressed highly in hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma, is a potential biomarker for immune checkpoint inhibitors. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2022; 14(10): 1933-1948

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v14/i10/1933.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v14.i10.1933

According to the GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates, the number of new liver cancer cases in China (410038) accounted for 45.7% of the global total (905077), and the fatality rate ranks second among malignant tumors in China[1,2]. In contrast to Western countries, 92.6% of liver cancer in China is caused by chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection [86% pure HBV infection and 6.7% coinfection of HBV and hepatitis C virus (HCV)], which often occurs with cirrhosis and has a worse prognosis[3].

Due to a strong correlation between the occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and the continuous immune inflammatory response, it is necessary to explore whether and how the tumor microenvironment (TME) acts on the progression of HCC[4]. The TME is where tumor cells exist and includes the extracellular matrix (ECM), fibroblasts, blood vessels, and various immune cells[5]. The ECM supports the structure of connective tissues and regulates cell functions, which consists of fibers, proteoglycans, hyaluronic acid, and glycoproteins[6]. In the TME, nonmalignant cells can help tumor cells proliferate, invade, and metastasize[7]. The TME in HCC plays an important role in promoting tumor progression and inhibiting antitumor immunity. For example, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are important immune cells involved in the microenvironment of HCC, and the low presence of CD86+ TAMs and high presence of CD206+ TAMs are significantly associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes, poor overall survival (OS), and shortened recurrence time[8]. The use of various targeted TME drugs for advanced unresectable HCC has been written into the guidelines[9-11]. VCAN is a proteoglycan that exists in the ECM of the TME, binds to integrins and integrin receptors or other ECM components on the cell surface, interacts with various cells in the TME, and participates in the adhesion, proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis of tumor cells[12]. VCAN promotes the invasion and metastasis of HCC in cell experiments[13,14], but the mechanism is still unclear. In addition, VCAN mRNA expression in human liver cancer tissues is higher than that in adjacent tissues[15], but whether VCAN could be a marker for the early diagnosis of HCC needs confirmation.

This study enrolled 100 patients with HBV-related liver diseases, including 50 with HCC and 50 with liver cirrhosis. VCAN mRNA expression and DNA methylation in serum were detected to analyze their correlation with clinical features. By using public datasets, we explored VCAN mRNA expression in HCC patients, the impact of VCAN on the clinical characteristics of patients, and the possible immune mechanism of VCAN in HBV-related HCC. Figure 1 more clearly describes the content of our study. We hope that this research will help to clarify the role of VCAN in HCC.

The RNA expression profiles and corresponding clinicopathological information of The Cancer Genome Atlas Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA-LIHC) were downloaded from TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/repository?facetTab=cases) on May 30, 2021. The transcriptome data of 374 cancer tissues and 50 paracancer tissues were annotated to extract the expression of VCAN.

VCAN mRNA expression in different cancer types was analyzed online with TIMER[16] (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/). R3.6.1 was used to perform differential analysis of VCAN mRNA in tumor tissues and adjacent tissues of patients from TCGA-LIHC. The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to evaluate the correlation between VCAN expression and the clinical characteristics of TCGA-LIHC patients. The OS of HCC patients with high and low expression of VCAN was compared by Kaplan-Meier analysis and the log-rank test with the survival package in R3.6.1.

During September 2021 to April 2022, 100 hospitalized HBV-related patients (50 with HCC and 50 with liver cirrhosis) were enrolled in the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. Patients with HCC and liver cirrhosis had to meet the diagnostic criteria of Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Liver Cancer in China (2019 edition)[17] and The Guidelines of Prevention and Treatment for Chronic Hepatitis B (2019 version)[18]. Among 50 HBV-related HCC patients, we collected ten pairs of tumor tissues and adjacent tissues of patients who underwent surgical therapy, and tumor-adjacent tissues were used as a control group to perform immunohistochemistry. The study was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University (Approval No. 2019-1093). Informed consent was required from all participants.

Total RNA was extracted from the mononuclear cells of collected peripheral blood with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, United States). Using total RNA as a template, cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription, and then real-time fluorescent quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II kit (Takara, Japan). The primer sequences of VCAN (primers synthesized by the Shanghai Shenggong Biological Engineering Co. Ltd.) are: Forward, 5’-TGGCATGAGAATGGCCAGTGGA-3’ and reverse, 5’- AAGCCAGAGACCCTCCCCCA-3’. OAZ1 was used as the internal reference. The primer sequences of OAZ1 (primers synthesized by the Shanghai Shenggong Biological Engineering) are: Forward, 5’-AGCAAGGACAGCTTTGCAGTTCTC-3’ and reverse, 5’- GATGCCCCGGTCTCACAATC-3’. The final Ct value of the target gene was the average of the Ct values of three replicate wells. The relative expression of VCAN mRNA was calculated according to the following formula: Relative expression of the target gene = 2-ΔCt, ΔCt = Ct(VCAN) - Ct(OAZ1).

The peripheral venous blood of the participants was collected, and genomic DNA was extracted with a blood DNA extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The extracted genomic DNA was treated with bisulfite using an EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo, Irvine, CA, United States) and then subjected to high-throughput sequencing after PCR amplification to obtain DNA methylation results.

Tissue samples were boiled in Tris/EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) for antigen retrieval, and immunohistochemistry was performed with primary antibody (EPR12277; Abcam, The United Kingdom), according to the SP Rabbit HRP Kit instructions (CE2035S, CWBIO, China).

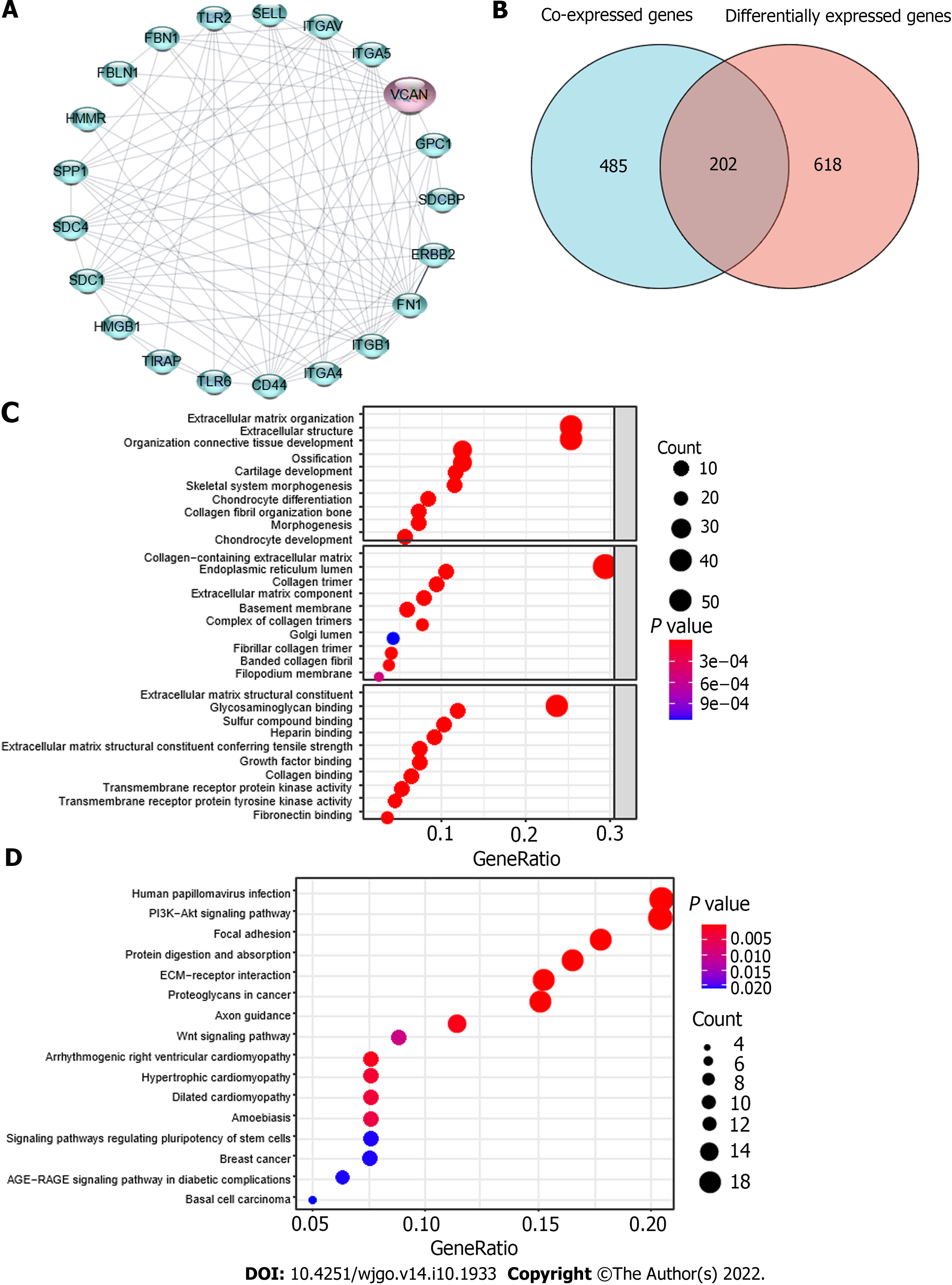

VENNY 2.1.0 (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html) was used to draw a Venn diagram containing coexpressed genes of VCAN (P < 0.05, r > 0.6), and differentially expressed genes between the high VCAN group and low VCAN group (median cut off, |log2 Fold change| >2, P < 0.05). These intersection genes were strongly related to the potential immune mechanism of VCAN in HCC, which were considered as VCAN-related genes. VCAN-related genes were annotated by Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEEG) gene set function using the clusterProfiler package of R3.6.1.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed on the group with high and low expression (median as the cutoff) of VCAN in TCGA-LIHC using GSEA 4.0.3. KEGG gene set (c2.cp.kegg. v7.4.symbols.gmt) was applied to explore the potential signaling pathway of VCAN in HCC (false discovery rate < 0.05)[19]. The proteins that may interact with VCAN were obtained with STRING (https://www.string-db.org/), and a corresponding protein-protein interaction (PPI) network diagram was drawn.

TME immune score and stroma score of TCGA-LIHC liver cancer tissues were calculated based on estimated algorithm using the R3.6.1 package estimate. Different algorithms (ssGSEA, CIBERSORTx, and TIMER) were used to evaluate intratumoral immune cell composition in patients with high and low expression of VCAN in TCGA-LIHC[16,20,21]. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) was calculated using the TCGA mutations package of R3.6.1. An immune checkpoint genes list was obtained from the published literature[22]. These gene expression data were extracted from transcripts of TCGA-LIHC to perform correlation analysis with VCAN expression.

All analyses and image preparation were performed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad, United States), Origin 2021b (OriginLab, United States), and R3.6.1. Normally distributed measurement data are represented by the mean ± SD, and those with a skewed distribution by the median (25%, 75%). Numerical data are represented by the number of cases. The means of two groups were compared by the t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and those of multiple groups were compared by analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test. The rates of multiple groups were compared by the χ2 test. P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

VCAN was highly expressed in a variety of tumor tissues, including breast cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, colon cancer, esophageal cancer, glioma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, renal chromophore cell carcinoma, renal papillary cell carcinoma, HCC, lung adenocarcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, gastric cancer, and thyroid cancer (Figure 2A). VCAN was significantly overexpressed in tumors in both paired and independent samples for patients from TCGA-LIHC (Figures 2B and C).

The patients were divided into two groups by the median of VCAN mRNA expression, and Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that the survival rate of the low VCAN expression group was significantly higher than that of the high-VCAN expression group in patients from TCGA-LIHC (Figure 2D). Univariate regression analysis showed that high level of VCAN was a marker of poor prognosis in HCC patients (Figure 3). There were significant differences in VCAN mRNA according to age, gender, pathological stage, and a-fetoprotein level of patients from TCGA-LIHC (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Low VCAN | High VCAN | P value |

| n | 187 | 187 | |

| Age, n (%) | 0.020 | ||

| 60 | 77 (20.6) | 100 (26.8) | |

| > 60 | 110 (29.5) | 86 (23.1) | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.015 | ||

| Female | 49 (13.1) | 72 (19.3) | |

| Male | 138 (36.9) | 115 (30.7) | |

| Pathologic stage, n (%) | 0.042 | ||

| I & II | 138 (39.4) | 122 (34.8) | |

| III & IV | 41 (11.7) | 45 (14.0) | |

| Histologic grade, n (%) | 0.090 | ||

| G1 | 34 (9.2) | 21 (5.7) | |

| G2 | 88 (23.8) | 90 (24.4) | |

| G3 | 54 (14.6) | 70 (19) | |

| G4 | 8 (2.2) | 4 (1.1) | |

| AFP (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 9 (3.5, 140) | 23 (5, 419) | 0.039 |

The clinical characteristics and relevant VCAN mRNA levels in the HBV-related HCC and cirrhosis patients are shown in Table 2. The baseline data including age, sex, antiviral therapy within 6 mo, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and Child-Pugh class were not significantly different between the two groups. There was no significant difference in VCAN mRNA between the two groups (Figure 4A), but there was a significant difference in VCAN methylation (Figure 4B). The methylation levels of each CpG site in the two groups of patients are shown in Figure 4C, which indicates that cg82767790, cg82767780, and cg82768850 differed significantly (P < 0.05). The correlation analysis between VCAN mRNA expression and the methylation levels of each site is shown in Figure 4D, which indicates that VCAN mRNA expression was not significantly related to any CpG sites of VCAN.

| Clinical feature | HCC (n = 50) | Liver cirrhosis (n = 50) | P value |

| Age | 57.55 ± 1.80 | 54.05 ± 2.22 | 0.227 |

| Sex (male/female) | 8/32 | 30/10 | 0.705 |

| Anti-virus treatment (yes/no) | 26/14 | 20/20 | 0.337 |

| HBeAg (+/-) | 7/33 | 6/34 | 0.144 |

| HBV-DNA (IU/mL): ≤ 102/> 102 | 22/18 | 11/29 | 0.100 |

| Child-Pugh: A/B&C | 28/17 | 8/32 | 0.168 |

| VCAN mRNA (%) | 4.45 ± 0.56 | 3.83 ± 0.61 | 0.147 |

| VCAN methylation | 0.056 ± 0.009 | 0.047 ± 0.005 | 0.022 |

According to the immunohistochemical results in the Human Protein Atlas (HPA)[23], VCAN is mainly expressed in the ECM in liver tumor tissues (Figure 5A). Immunohistochemical results of hepatocellular and adjacent tumor tissue showed that VCAN was expressed more in tumor tissue than in adjacent tissue, and VCAN was mainly distributed in the ECM (Figure 5B), which was similar to the result in the HPA (Figure 5A).

The participants were divided into either a group of patients with high VCAN mRNA expression or a group of patients with low VCAN mRNA expression in blood using the median as the cutoff. Comparison of clinical characteristics between the two groups showed that the expression of VCAN was associated with HBeAg, HBV DNA, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein-cholesterol, white blood cells, platelets, and prothrombin activity (Table 3).

| Variable | VCAN RNA expression (median as cutoff) | P value | |

| Low | High | ||

| Age | 56.60 ± 8.45 | 55.00 ± 9.82 | 0.552 |

| Male/female | 39/11 | 38/12 | 0.705 |

| Anti-viral treatment/no treatment | 23/27 | 35/15 | 0.110 |

| HBeAg (+)/(-) | 21/29 | 5/45 | 0.028 |

| HBV-DNA (IU/mL): ≤ 102/> 102 | 13/37 | 34/16 | 0.025 |

| Child-Pugh: A/B&C | 35/15 | 31/19 | 0.490 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 11.59 (3.47, 135.68) | 21.43 (1.84, 210.88) | 0.698 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 26.37 (18.70, 50.25) | 16.26 (11.47, 29.14) | 0.035 |

| Direct bilirubin (μmol/L) | 8.44 (6.64, 27.92) | 5.28 (3.51, 13.96) | 0.043 |

| Indirect bilirubin (μmol/L) | 17.21 (12.23, 22.83) | 10.51 (6.78, 13.39) | 0.007 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.90 ± 0.82 | 3.56 ± 0.81 | 0.015 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.74 ± 0.59 | 2.25 ± 0.59 | 0.009 |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 3.54 ± 1.40 | 6.12 ± 2.40 | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 58.69 ± 13.24 | 57.31 ± 14.48 | 0.302 |

| Platelet (× 109/L) | 76.60 ± 49.14 | 172.6 ± 87.01 | < 0.001 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 11.85 (10.85, 15.55) | 11.15 (10.43, 11.83) | 0.030 |

| Prothrombin activity (%) | 75.64 ± 21.15 | 89.37 ± 12.74 | 0.018 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 186.00 ± 49.53 | 267.55 ± 111.17 | 0.006 |

The PPI network diagram (Figure 6A) consists of proteins potentially interacting with VCAN, which are mainly proteoglycan molecules, ECM molecules, and inflammatory factors. After co-expression analysis and differential expression analysis of high and low expression of VCAN, we obtained 687 VCAN co-expressed genes and 820 differentially expressed genes; 202 intersection genes (VCAN-related genes) are listed in Figure 6B.

The 202 intersection genes were subjected to functional annotation (Figure 6C). These genes mainly participate in biological processes involved in ECM organization, extracellular structure organization, and connective tissue development. VCAN-related genes participate in the formation of cellular components including collagen-containing ECM, endoplasmic reticulum lumen, collagen trimer, and basement membrane, and they performed molecular functions such as ECM structural constituents, glycosaminoglycan binding, and sulfur compound binding. KEGG analysis and GSEA showed that VCAN-related genes were mainly enriched in the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, focal adhesion, protein digestion and absorption, ECM-receptor interaction, and proteoglycans in cancer (Table 4, Figure 6D).

| Name | Size | ES | NES | NOM P value | FDR Q value |

| KEGG_FC_GAMMA_R_MEDIATED_PHAGOCYTOSIS | 96 | -0.739 | -2.154 | < 0.001 | 5.13E-04 |

| KEGG_PATHOGENIC_ESCHERICHIA_COLI_INFECTION | 56 | -0.720 | -2.046 | < 0.001 | 5.91E-04 |

| KEGG_ECM_RECEPTOR_INTERACTION | 84 | -0.716 | -2.162 | < 0.001 | 8.55E-04 |

| KEGG_AXON_GUIDANCE | 129 | -0.695 | -2.191 | < 0.001 | 0.0015376 |

| KEGG_DILATED_CARDIOMYOPATHY | 90 | -0.680 | -2.112 | < 0.001 | 4.91E-04 |

| KEGG_APOPTOSIS | 87 | -0.678 | -2.042 | < 0.001 | 6.26E-04 |

| KEGG_CHEMOKINE_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 188 | -0.678 | -2.127 | < 0.001 | 3.83E-04 |

| KEGG_LEUKOCYTE_TRANSENDOTHELIAL_MIGRATION | 116 | -0.677 | -2.187 | < 0.001 | 7.69E-04 |

| KEGG_FOCAL_ADHESION | 199 | -0.675 | -2.148 | < 0.001 | 4.28E-04 |

| KEGG_HYPERTROPHIC_CARDIOMYOPATHY_HCM | 83 | -0.673 | -2.128 | < 0.001 | 4.30E-04 |

| KEGG_CELL_ADHESION_MOLECULES_CAMS | 131 | -0.663 | -2.076 | < 0.001 | 7.01E-04 |

| KEGG_REGULATION_OF_ACTIN_CYTOSKELETON | 213 | -0.659 | -2.158 | < 0.001 | 6.42E-04 |

| KEGG_GAP_JUNCTION | 90 | -0.656 | -2.052 | < 0.001 | 6.23E-04 |

| KEGG_ENDOCYTOSIS | 181 | -0.656 | -2.084 | < 0.001 | 8.02E-04 |

| KEGG_MELANOGENESIS | 101 | -0.630 | -2.129 | < 0.001 | 4.92E-04 |

| KEGG_VASCULAR_SMOOTH_MUSCLE_CONTRACTION | 114 | -0.629 | -2.097 | < 0.001 | 7.21E-04 |

| KEGG_CYTOKINE_CYTOKINE_RECEPTOR_INTERACTION | 264 | -0.625 | -2.119 | < 0.001 | 3.44E-04 |

| KEGG_PATHWAYS_IN_CANCER | 325 | -0.621 | -2.111 | < 0.001 | 4.50E-04 |

| KEGG_MAPK_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 267 | -0.602 | -2.080 | < 0.001 | 7.48E-04 |

| KEGG_CALCIUM_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 177 | -0.582 | -2.057 | < 0.001 | 6.60E-04 |

The results of three different algorithms showed that immune cell infiltration was significantly different between the high and low VCAN expression groups (Figures 7A-C). The stromal score, immune score, and tumor purity of TCGA-LIHC tumor tissues were significantly different between the two groups (Figures 8A and B). VCAN was significantly correlated to all 47 immune checkpoint genes (Figure 8C). In addition, TMB in the low VCAN group was significantly higher than that in the high VCAN group (Figure 8D). Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) were significantly related to VCAN mRNA expression (Figure 8E). Based on the significant correlation between VCAN and immune checkpoint genes and TMB[24], VCAN is possible to predict sensitivity to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy in HCC.

Our study found no significant difference in VCAN mRNA in serum mononuclear cells between HBV-related patients and controls, but the analysis based on BBCancer database showed that VCAN in HCC patients was significantly higher than that in normal controls (Supplementary Figure 1A). The possible reasons were as follows: The public database detected VCAN expression levels in extracellular vesicles in serum, while we detected VCAN expression levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, considering that VCAN is mainly expressed on the cell surface. Exosomes are vesicles secreted by a variety of living cells, which contain a variety of components such as protein and RNA. Tumor-derived or tumor-related exosomes play an important role in the regulation of tumor development, especially through the TME, so the result would have been different if we had collected plasma exosomes from patients to measure VCAN RNA levels[25]. The reason why we made the assumption that VCAN methylation was significantly lower in HCC patients’ blood, which is consistent with the result from TCGA-LIHC, was that VCAN is highly expressed in tumor tissue.

VCAN is highly expressed in tumor tissues, but especially higher in tumor tissues of HCC associated with viruses (Liver Cancer-RIKEN, Japan Project from International Cancer Genome Consortium) compared with HCC secondary to alcohol consumption and adiposity (ICGA-LICA-FR, Supplementary Figures 1B-D). In addition, when there is cirrhosis of the liver, viral hepatitis (including HBV and HCV) is more likely to progress to liver cancer than fatty hepatitis (including alcoholic and nonalcoholic), but when there is no cirrhosis of the liver, the opposite is true[26], which suggests that different causes have different mechanisms of progression from liver cirrhosis to cancer. VCAN expression in serum mononuclear cells is related to the characterization of HBeAg, which has been confirmed to promote the progression of HCC. This also proves that VCAN may promote the occurrence of liver cancer through interaction with HBeAg.

To investigate why VCAN is highly expressed in HCC tumor tissue or how it works, we also predicted VCAN-interacting proteins. The proteins that may interact with VCAN obtained by STRING online (Figure 5A) include three main types: Decorin, biglycan, and other ECM components mainly involved in collagen production, physiological activities such as cell adhesion, apoptosis, and cellular immunity; Toll-like receptor (TLR)1 and TLR2, factors involved in immune response and inflammatory response; and integrin/integrin receptors and various protein kinases, which participate in angiogenesis and cell adhesion. A similar conclusion was drawn by the GO analysis, KEGG analysis, and the GSEA of patients with high VCAN expression (Figures 5C and D, Table 4), which showed that VCAN affects the occurrence of HCC mainly through ECM-related signaling pathways and the immune inflammatory response.

To explore the role of VCAN in immunoregulation of liver cancer, we analyzed the correlation between VCAN expression and tumor immune cell infiltration of TCGA-LIHC (Figures 6A-C), which indicated that VCAN plays a role in T-cell regulation in HCC. PD-1 regulates the immune system and promotes tolerance by inhibiting T-cell inflammatory activity. Clinical trials of nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and atezolizumab (PD-1 inhibitors) have shown they prolong OS of HCC patients and delay tumor progression[27-29], and tremelimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor) has shown similar results[30]. Several guidelines recommend ICIs in combination with antiangiogenic agents as first-line therapy for advanced HCC[9-11]. The efficacy of ICIs can be predicted by TMB and immune checkpoint gene expression levels[31,32]. In our study, differential expression of PD-1 and CTLA-4 in the high and low VCAN groups, as well as significantly different TMB, showed that VCAN could be a potential biomarker of sensitivity to ICIs in HCC. However, only transcription data of a cohort of HCC patients treated with ICIs could directly explain whether VCAN could be a biomarker for the efficacy of such immunotherapy.

In addition, CD44 deserves attention when studying the role of VCAN in immunoregulation of liver cancer. PPI shows that CD44 is the most likely immune-related protein to interact with VCAN. Both VCAN and CD44 are involved in the adhesion and migration of T cells through the ECM, and both of their intermediate molecules are hyaluronic acid[33]. The immune cells in the TME of HCC interact with effector molecules to alter the immune system and promote or inhibit the growth of HCC[34]. Immunotherapy has been listed as a fourth-line treatment after surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, and has been promoted as a first-line treatment for advanced unresectable liver cancer. Immune checkpoints block T-cell activation and promote T-cell failure to regulate immune escape in cancer[35]. ICIs have been widely used in melanoma, nonsmall cell lung cancer, etc. Immune and inflammatory responses play a key role in the development and progression of HCC, so ICIs are supposed to be effective in HCC. Several clinical trials of PD-1/CTLA4 inhibitors in HCC are under way, and have proved their efficacy[27-29]. VCAN deserves attention due to its potential prediction of sensitivity to PD-1/CTLA4 inhibitors.

In this study, we found that VCAN was highly expressed in HCC tumor tissues and could possibly be a biomarker of prognosis and sensitivity to ICIs in HCC patients. Our study had the following limitations: Due to the lack of follow-up for HCC patients, survival data were not available for analysis. In addition, we did not extract exosomes from patients’ serum for detection. We will further study the effects of the above defects on VCAN and its related genes in HBV-related liver diseases.

We analyzed VCAN expression and corresponding clinical features of patients from the public database and our HBV-related patients, and concluded that VCAN may affect the occurrence of liver cancer and the prognosis of HCC patients through ECM signaling pathways and inflammatory immune response signaling pathways. In addition, VCAN may be a biomarker for sensitivity to ICIs, which needs to be verified.

Existing studies have shown that chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, including VCAN, is a key component in the tumor microenvironment and may play an important role in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

The role of VCAN in HCC has not yet been elucidated, especially in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related HCC.

This study aimed to investigate the expression and potential mechanism of action of VCAN in HCC.

We tested VCAN expression in serum of patients with HBV-associated HCC and cirrhosis, and explore the underlying mechanism of VCAN in HCC by bioinformatics methods.

VCAN may be a possible biomarker for the prognosis of HCC. VCAN was associated with HBV e antigen in HBV infected patients. VCAN may play a role in HCC through the extracellular matrix signaling pathway and inflammatory immune response.

High VCAN level could be a possible biomarker for the poor prognosis of HCC, and its immunomodulatory mechanism in HCC deserves attention.

Future studies will be conducted to explore the immune mechanism of VCAN in HBV-associated HCC.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gupta T, India; Yao YQ, China S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64668] [Article Influence: 16167.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (176)] |

| 2. | Zheng RS, Sun KX, Zhang SW, Zeng HM, Zou XN, Chen R, Gu XY, Wei WW, He J. [Report of cancer epidemiology in China, 2015]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2019;41:19-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang M, Wang Y, Feng X, Wang R, Zeng H, Qi J, Zhao H, Li N, Cai J, Qu C. Contribution of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus to liver cancer in China north areas: Experience of the Chinese National Cancer Center. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;65:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Affo S, Yu LX, Schwabe RF. The Role of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Fibrosis in Liver Cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2017;12:153-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zeltz C, Primac I, Erusappan P, Alam J, Noel A, Gullberg D. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in desmoplastic tumors: emerging role of integrins. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;62:166-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Paolillo M, Schinelli S. Extracellular Matrix Alterations in Metastatic Processes. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lu C, Rong D, Zhang B, Zheng W, Wang X, Chen Z, Tang W. Current perspectives on the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: challenges and opportunities. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 50.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dong P, Ma L, Liu L, Zhao G, Zhang S, Dong L, Xue R, Chen S. CD86⁺/CD206⁺, Diametrically Polarized Tumor-Associated Macrophages, Predict Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patient Prognosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gordan JD, Kennedy EB, Abou-Alfa GK, Beg MS, Brower ST, Gade TP, Goff L, Gupta S, Guy J, Harris WP, Iyer R, Jaiyesimi I, Jhawer M, Karippot A, Kaseb AO, Kelley RK, Knox JJ, Kortmansky J, Leaf A, Remak WM, Shroff RT, Sohal DPS, Taddei TH, Venepalli NK, Wilson A, Zhu AX, Rose MG. Systemic Therapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:4317-4345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 83.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Greten TF, Abou-Alfa GK, Cheng AL, Duffy AG, El-Khoueiry AB, Finn RS, Galle PR, Goyal L, He AR, Kaseb AO, Kelley RK, Lencioni R, Lujambio A, Mabry Hrones D, Pinato DJ, Sangro B, Troisi RI, Wilson Woods A, Yau T, Zhu AX, Melero I. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sun HC, Zhou J, Wang Z, Liu X, Xie Q, Jia W, Zhao M, Bi X, Li G, Bai X, Ji Y, Xu L, Zhu XD, Bai D, Chen Y, Dai C, Guo R, Guo W, Hao C, Huang T, Huang Z, Li D, Li T, Li X, Liang X, Liu J, Liu F, Lu S, Lu Z, Lv W, Mao Y, Shao G, Shi Y, Song T, Tan G, Tang Y, Tao K, Wan C, Wang G, Wang L, Wang S, Wen T, Xing B, Xiang B, Yan S, Yang D, Yin G, Yin T, Yin Z, Yu Z, Zhang B, Zhang J, Zhang S, Zhang T, Zhang Y, Zhang A, Zhao H, Zhou L, Zhang W, Zhu Z, Qin S, Shen F, Cai X, Teng G, Cai J, Chen M, Li Q, Liu L, Wang W, Liang T, Dong J, Chen X, Wang X, Zheng S, Fan J; Alliance of Liver Cancer Conversion Therapy, Committee of Liver Cancer of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association. Chinese expert consensus on conversion therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (2021 edition). Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2022;11:227-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wu YJ, La Pierre DP, Wu J, Yee AJ, Yang BB. The interaction of versican with its binding partners. Cell Res. 2005;15:483-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhangyuan G, Wang F, Zhang H, Jiang R, Tao X, Yu D, Jin K, Yu W, Liu Y, Yin Y, Shen J, Xu Q, Zhang W, Sun B. VersicanV1 promotes proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma through the activation of EGFR-PI3K-AKT pathway. Oncogene. 2020;39:1213-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xia L, Huang W, Tian D, Zhang L, Qi X, Chen Z, Shang X, Nie Y, Wu K. Forkhead box Q1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by transactivating ZEB2 and VersicanV1 expression. Hepatology. 2014;59:958-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Naboulsi W, Megger DA, Bracht T, Kohl M, Turewicz M, Eisenacher M, Voss DM, Schlaak JF, Hoffmann AC, Weber F, Baba HA, Meyer HE, Sitek B. Quantitative Tissue Proteomics Analysis Reveals Versican as Potential Biomarker for Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2016;15:38-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu JS, Li B, Liu XS. TIMER: A Web Server for Comprehensive Analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e108-e110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2728] [Cited by in RCA: 4092] [Article Influence: 511.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Department of Medical Administration, National Health and Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. [Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer in China (2019 edition)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2020;28:112-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases; Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. [The guidelines of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B (2019 version)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2019;27:938-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545-15550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27252] [Cited by in RCA: 37503] [Article Influence: 1875.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Newman AM, Steen CB, Liu CL, Gentles AJ, Chaudhuri AA, Scherer F, Khodadoust MS, Esfahani MS, Luca BA, Steiner D, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. Determining cell type abundance and expression from bulk tissues with digital cytometry. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:773-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1098] [Cited by in RCA: 2716] [Article Influence: 452.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Barbie DA, Tamayo P, Boehm JS, Kim SY, Moody SE, Dunn IF, Schinzel AC, Sandy P, Meylan E, Scholl C, Fröhling S, Chan EM, Sos ML, Michel K, Mermel C, Silver SJ, Weir BA, Reiling JH, Sheng Q, Gupta PB, Wadlow RC, Le H, Hoersch S, Wittner BS, Ramaswamy S, Livingston DM, Sabatini DM, Meyerson M, Thomas RK, Lander ES, Mesirov JP, Root DE, Gilliland DG, Jacks T, Hahn WC. Systematic RNA interference reveals that oncogenic KRAS-driven cancers require TBK1. Nature. 2009;462:108-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1822] [Cited by in RCA: 2696] [Article Influence: 168.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xu D, Liu X, Wang Y, Zhou K, Wu J, Chen JC, Chen C, Chen L, Zheng J. Identification of immune subtypes and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma based on immune checkpoint gene expression profile. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;126:109903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist PH, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Pontén F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7696] [Cited by in RCA: 10540] [Article Influence: 1054.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chan TA, Yarchoan M, Jaffee E, Swanton C, Quezada SA, Stenzinger A, Peters S. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: utility for the oncology clinic. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:44-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1568] [Cited by in RCA: 1878] [Article Influence: 313.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Seo N, Akiyoshi K, Shiku H. Exosome-mediated regulation of tumor immunology. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:2998-3004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mittal S, El-Serag HB, Sada YH, Kanwal F, Duan Z, Temple S, May SB, Kramer JR, Richardson PA, Davila JA. Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Absence of Cirrhosis in United States Veterans is Associated With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:124-31.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 492] [Article Influence: 54.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Yau T, Kang YK, Kim TY, El-Khoueiry AB, Santoro A, Sangro B, Melero I, Kudo M, Hou MM, Matilla A, Tovoli F, Knox JJ, Ruth He A, El-Rayes BF, Acosta-Rivera M, Lim HY, Neely J, Shen Y, Wisniewski T, Anderson J, Hsu C. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Previously Treated With Sorafenib: The CheckMate 040 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:e204564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 908] [Cited by in RCA: 970] [Article Influence: 194.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Merle P, Kudo M, Bouattour M, Lim HY, Breder V, Edeline J, Chao Y, Ogasawara S, Yau T, Garrido M, Chan SL, Knox J, Daniele B, Ebbinghaus SW, Chen E, Siegel AB, Zhu AX, Cheng AL; KEYNOTE-240 investigators. Pembrolizumab As Second-Line Therapy in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:193-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1365] [Cited by in RCA: 1341] [Article Influence: 268.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sonbol MB, Riaz IB, Naqvi SAA, Almquist DR, Mina S, Almasri J, Shah S, Almader-Douglas D, Uson Junior PLS, Mahipal A, Ma WW, Jin Z, Mody K, Starr J, Borad MJ, Ahn DH, Murad MH, Bekaii-Saab T. Systemic Therapy and Sequencing Options in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:e204930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Duffy AG, Ulahannan SV, Makorova-Rusher O, Rahma O, Wedemeyer H, Pratt D, Davis JL, Hughes MS, Heller T, ElGindi M, Uppala A, Korangy F, Kleiner DE, Figg WD, Venzon D, Steinberg SM, Venkatesan AM, Krishnasamy V, Abi-Jaoudeh N, Levy E, Wood BJ, Greten TF. Tremelimumab in combination with ablation in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;66:545-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 640] [Article Influence: 80.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ott PA, Bang YJ, Piha-Paul SA, Razak ARA, Bennouna J, Soria JC, Rugo HS, Cohen RB, O'Neil BH, Mehnert JM, Lopez J, Doi T, van Brummelen EMJ, Cristescu R, Yang P, Emancipator K, Stein K, Ayers M, Joe AK, Lunceford JK. T-Cell-Inflamed Gene-Expression Profile, Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression, and Tumor Mutational Burden Predict Efficacy in Patients Treated With Pembrolizumab Across 20 Cancers: KEYNOTE-028. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:318-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 713] [Cited by in RCA: 669] [Article Influence: 111.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, Shah M, Shapira-Frommer R, Nakagawa K, Chung HC, Kindler HL, Lopez-Martin JA, Miller WH Jr, Italiano A, Kao S, Piha-Paul SA, Delord JP, McWilliams RR, Fabrizio DA, Aurora-Garg D, Xu L, Jin F, Norwood K, Bang YJ. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1353-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1756] [Cited by in RCA: 1628] [Article Influence: 325.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Evanko SP, Potter-Perigo S, Bollyky PL, Nepom GT, Wight TN. Hyaluronan and versican in the control of human T-lymphocyte adhesion and migration. Matrix Biol. 2012;31:90-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Oura K, Morishita A, Tani J, Masaki T. Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Immunosuppressive Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 71.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Abril-Rodriguez G, Ribas A. SnapShot: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:848-848.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |