Published online Mar 15, 2021. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v13.i3.174

Peer-review started: December 10, 2020

First decision: December 31, 2020

Revised: January 9, 2021

Accepted: February 1, 2021

Article in press: February 1, 2021

Published online: March 15, 2021

Processing time: 89 Days and 1.1 Hours

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is widely accepted for early gastric cancer (EGC) without lymph node metastasis, although ESD is challenging, even for small lesions, in the greater curvature (GC) of the upper (U) and middle (M) thirds of the stomach. Grasping forceps-assisted endoscopic resection (GF-ER) is a type of endoscopic mucosal resection that is performed via a double-channel endoscope.

To investigate the safety and efficacy of GF-ER vs ESD in the GC of the stomach’s U and M regions.

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 506 patients who underwent ER of 522 EGC lesions in the stomach’s U and M regions in three institutions between January 2016 and May 2020. Nine lesions from eight patients who underwent GF-ER for EGC (the GF-ER group) were compared to 63 lesions from 63 patients who underwent ESD (the ESD group). We also performed a subgroup analysis of small lesions (≤ 10 mm) in 6 patients (7 lesions) from the GF-ER group and 20 patients (20 lesions) from the ESD group.

There were no statistically significant differences between the GF-ER and ESD groups in the en bloc resection rates (100% vs 100%) and the R0 resection rates (100% vs 98.4%). The median procedure time in the GF-ER group was shorter than that in the ESD group (4.0 min vs 55.0 min, P < 0.01). There were no adverse events in the GF-ER group, although five perforations (8.0%) and 1 case of postoperative bleeding (1.6%) were observed in the ESD group. When we only considered lesions that were ≤ 10 mm, the median procedure time in the GF-ER group was still shorter than that in the ESD group (4.0 min vs 35.0 min, P < 0.01). There were no adverse events in the GF-ER group, although 1 case of perforation (1.6%) were observed in the ESD group.

These findings suggest that GF-ER may be an effective therapeutic option for small lesions in the GC of the stomach’s U and M regions.

Core Tip: Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is widely accepted for early gastric cancer (EGC), although ESD is challenging, even for small lesions, in the greater curvature of the upper and middle thirds of the stomach. The major discoveries and findings in this study are; we found that grasping forceps-assisted endoscopic resection achieved en bloc and R0 resections with significantly shorter procedure times (vs ESD), without any adverse events. Although ESD is considered the first-line treatment for EGC, it is not always necessary to treat lesions in all areas using ESD, and endoscopic mucosal resection is a feasible option if en bloc resection is considered possible, as it can be performed easily and quickly.

- Citation: Ichijima R, Suzuki S, Esaki M, Horii T, Kusano C, Ikehara H, Gotoda T. Efficacy and safety of grasping forceps-assisted endoscopic resection for gastric neoplasms: A multi-centre retrospective study. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2021; 13(3): 174-184

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v13/i3/174.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v13.i3.174

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was developed in Japan during the 1990s and is now widely used to treat early gastric cancer (EGC), as it allows en bloc resection of large lesions and ulcers and facilitates an accurate pathological diagnosis[1-3]. However, relative to in other regions, ESD is considered a technically challenging procedure in the upper (U) and middle (M) thirds of the stomach, especially in the greater curvature (GC). This is because intraoperative bleeding is more common in the U and M areas, which can prolong the procedural time. Furthermore, ESD in these regions is associated with increased rates of adverse events, such as perforation[4-6]. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is considered a technically simpler procedure, relative to ESD, and EMR requires less time, although it may not provide complete resection of large lesions. Despite the challenges associated with ESD, and the simplicity of EMR, almost all endoscopic resections (ERs) for gastric cancer in Japan are performed via ESD.

Grasping forceps-assisted ER (GF-ER) is an EMR procedure that uses an assistant device, which is similar to a cap or ligation device for EMR[7-10]. At the centres that were involved in this study, GF-ER was performed for lesions that fulfilled the following criteria: (1) The EGC was located in the U or M region of the stomach; (2) Small (diameter: ≤ 10 mm) or pedunculated lesions; and (3) The endoscopist judged en bloc resection feasible. Although GF-ER is a conventionally practiced technique, only a few studies have described the outcomes of GF-ER for EGC. Furthermore, since ESD has become established, no new studies have compared the therapeutic outcomes of GF-ER and ESD in the challenging U and M stomach regions. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of GF-ER and ESD in the GC of the stomach’s U and M regions.

This multi-centre, retrospective, observational cohort study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Nihon University Surugadai Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients before the ESD and GF-ER procedures. We collected and retrospectively reviewed data from the patients’ medical records.

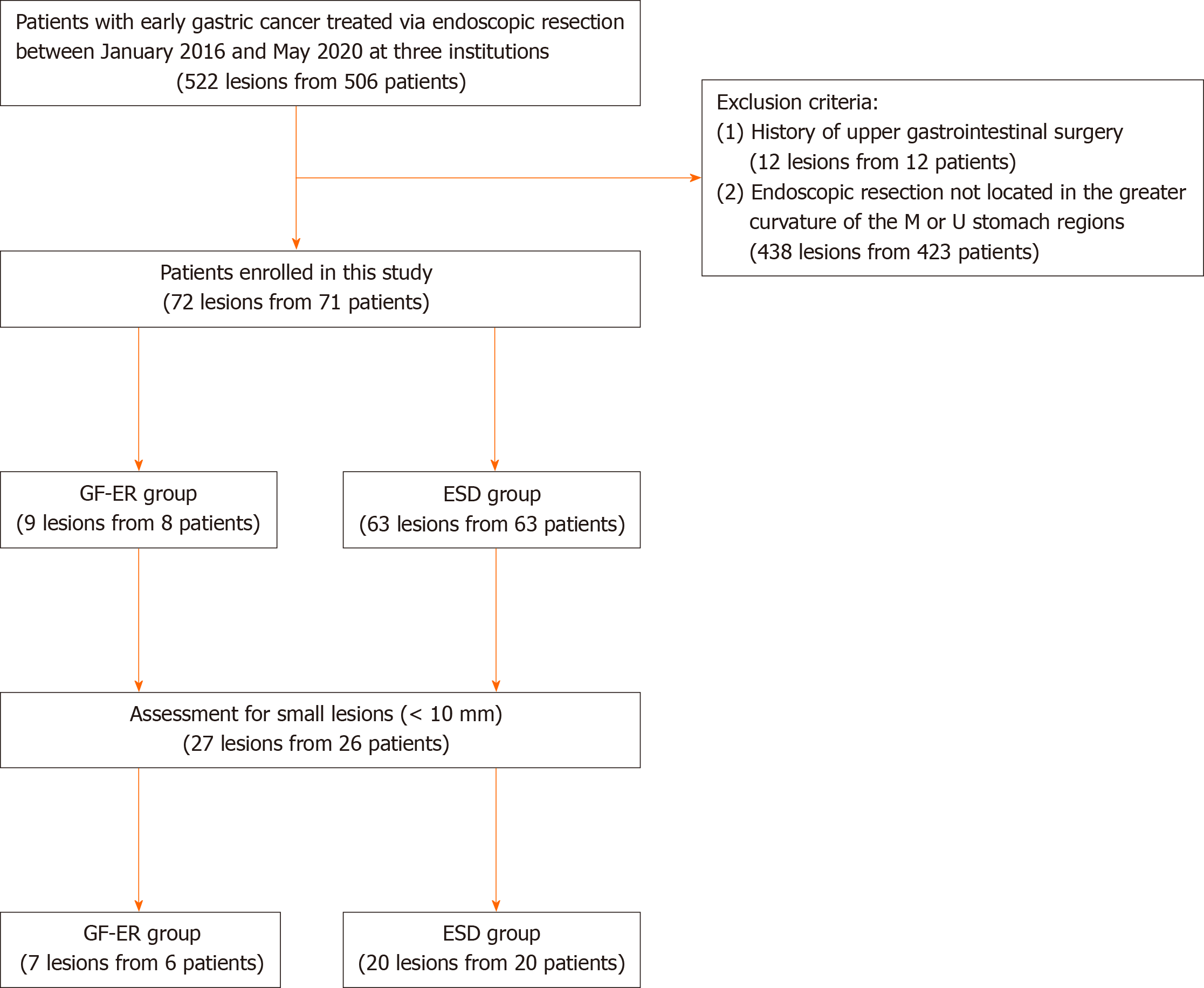

Figure 1 shows the study flowchart. A total of 506 patients underwent ER for 522 EGC lesions between January 2016 and May 2020 at three institutions (Nihon University Surugadai Hospital, Nihon University Itabashi Hospital, and Yuri-Kumiai General Hospital). Patients were excluded if they had previously undergone gastric surgery or if they had undergone ER for lesions in the lower (L) stomach region, lesser curvature, anterior side wall, or posterior side wall. Thus, we ultimately compared the safety and efficacy outcomes for 9 lesions from 8 patients who underwent GF-ER for EGC in the GC of the stomach’s U and M regions (the GF-ER group) and 63 lesions from 63 patients who underwent ESD (the ESD group). We also performed a subgroup analysis of patients with small lesions (diameter: ≤ 10 mm), which included 7 lesions from 6 patients in the GF-ER group and 20 lesions from 20 patients in the ESD group.

All GF-ER and ESD procedures were performed at the three institutions. All patients were hospitalised on the day before the GF-ER or ESD procedure and maintained a restricted diet for 2 d after the procedure. Patients were discharged at 1 wk after the procedure if they did not experience any adverse events, although discharge was delayed for patients who developed perforations or bleeding. All patients were sedated using midazolam or propofol and pentazocine. High-frequency currents produced by ERBE-ICC200 or VIO300D electrosurgical generator units (ERBE Elektromedzin, GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) were used in the Endocut mode (effect 2), at 50 W for the forced coagulation mode, and at 50 W for mucosal resection or submucosal dissection during the GF-ER and ESD procedures. Haemostasis was achieved using the soft coagulation mode at 80 W. The GF-ER procedures were performed using the GIF-Q260J endoscope and the ESD procedures were performed using the GIF2TQ260M endoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The ESD procedures were performed using the IT Knife2 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), Clutch Cutter (Fujifilm Medical, Tokyo, Japan), Dual Knife (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), or Splash M-knife (HOYA Corp., Pentax, Tokyo, Japan) based on the endoscopist’s preference. A short hood (D-201 – 13404 Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used on the endoscope tip.

The ESD procedure was started by using an argon plasma coagulation or needle knife to mark around the lesion. The surrounding submucosa was then injected with a saline solution and, once the area was sufficiently elevated, a complete circumferential incision was made approximately 5 mm outside the marking. The submucosa was then dissected to complete the en bloc resection. During ESD, the dental floss method could be used for traction assistance, based on the endoscopist’s preference[11].

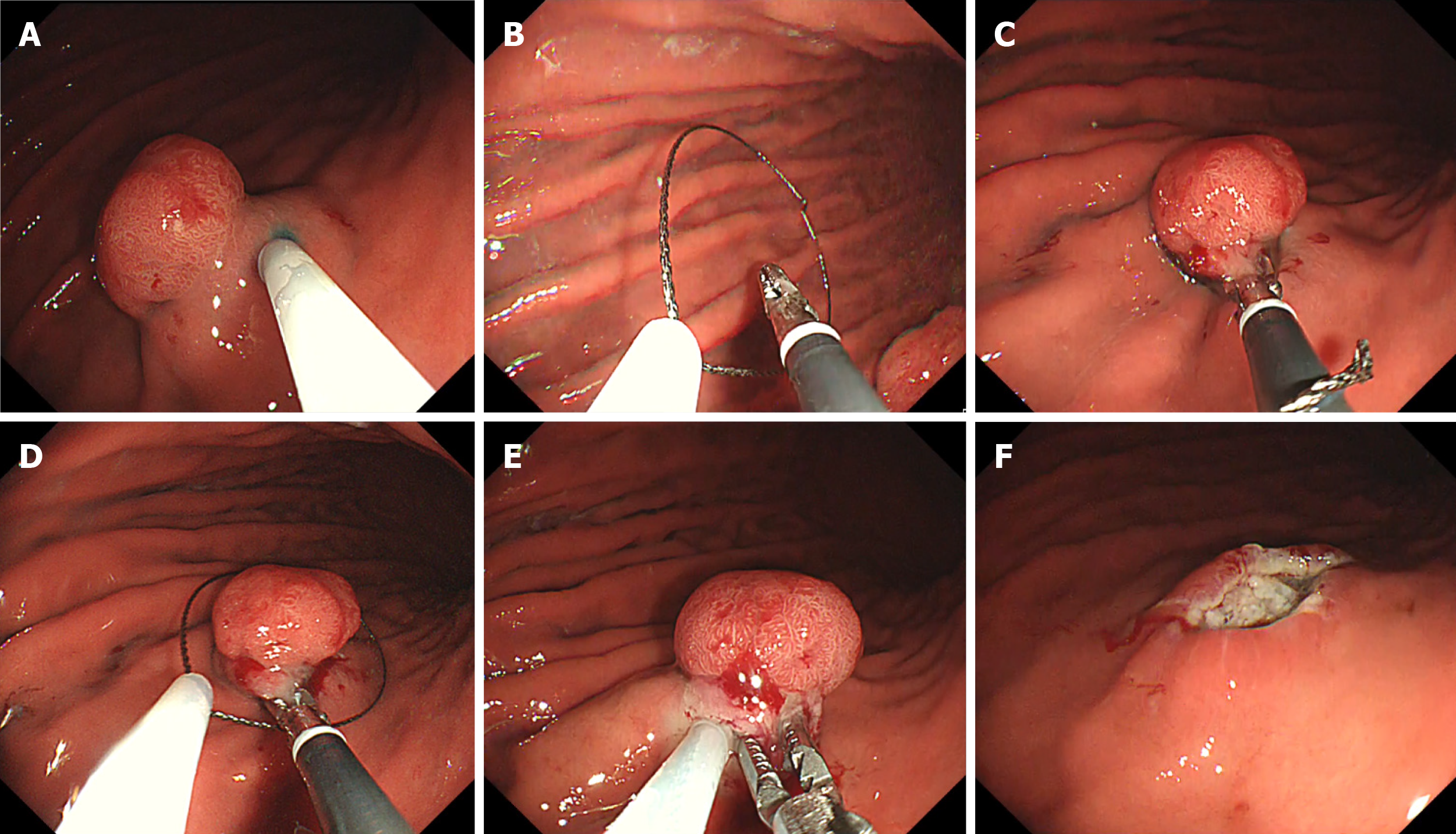

The GF-ER procedure was started by creating a mark around the lesion in the same manner as for the ESD procedure. After the marking, a saline solution was injected locally into the submucosa around the lesion to achieve sufficient elevation (Figure 2A). Next, the snare and grasping forceps were deployed from the double-channel scope (Figure 2B). The grasping forceps were used to firmly grasp the elevated mucosa (Figure 2C) and the snare was then placed around the grasped mucosa (Figure 2D). After ensuring that the entire lesion was inside the snare, the resection was performed (Figure 2E). Finally, we checked the mucosal defect for any residual tumour (Figure 2F).

Specimens resected during ESD and GF-ER were pinned, preserved in formalin, and cut into 2–3 mm sections. Histological diagnoses were performed by pathologists at the hospitals. Pathological diagnoses were made by gastrointestinal pathologists according to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Classification and the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines[12,13].

The primary outcome was the procedural time and the secondary outcomes were the rates of en bloc resection, R0 resection, and adverse events (such as postoperative bleeding and perforations). Tumour location was defined according to the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma based on the affected gastric region (U, M, or L) and gastric surface (lesser curvature, GC, anterior wall, or posterior wall)[12]. The GF-ER or ESD procedural times were defined as the times from the first submucosal injection to the resection of the lesion. En bloc resection was defined as a resection made without having to resort to a piecemeal resection. R0 resection was defined as en bloc resection that achieved negative horizontal and vertical tumour margins. Perforations were defined as intraoperative exposures of the mesenteric fat or free air, as confirmed by diagnostic imaging based on a post-procedural complaint of abdominal pain. Delayed bleeding was defined as an endoscopic or surgical haemostatic procedure performed for subjective symptoms, such as anaemia, haematemesis, or melena.

Continuous variables were reported as median (interquartile range) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. The Fisher test was used to compare categorical variables. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR software (version 1.27; Saitama Medical Centre, Jichi Medical University, Japan)[14].

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 8 patients and 9 lesions from the GF-ER group and the 63 patients and 63 lesions from the ESD group. Tumour size was significantly smaller in the GF-ER group than in the ESD group (7.0 mm vs 16.0 mm, P < 0.01). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of tumour morphology, depth, or histology. Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the patients with small lesions (diameter: ≤ 10 mm) according to their procedure. There was no significant difference in tumour size between the GF-ER and ESD groups in this subgroup.

| GF-ER | ESD | P value | |

| Age, yr | |||

| Median (IQR) | 68.0 (54-80) | 75.0 (66-82) | 0.28 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 6 (75.0) | 45 (71.4) | 1 |

| Female | 2 (25.0) | 18 (28.6) | |

| Morphology, n (%) | |||

| Flat or depressed | 5 (55.6) | 46 (73.0) | 0.43 |

| Elevated | 4 (44.4) | 17 (27.0) | |

| Ulceration, n (%) | |||

| Presence | 0 (0) | 4 (6.3) | 1 |

| Absence | 9 (100) | 59 (93.7) | |

| Tumor size, mm | |||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (4-11) | 16 (9-22) | < 0.01 |

| Tumor depth, n (%) | |||

| Mucosa | 6 (66.7) | 49 (77.8) | 0.43 |

| Submucosa | 3 (33.3) | 14 (22.2) | |

| Histology, n (%) | |||

| Differentiated | 9 (100) | 49 (77.8) | 0.31 |

| Undifferentiated | 0 (0) | 14 (22.2) |

| GF-ER | ESD | P value | |

| Age, yr | |||

| Median (IQR) | 67.5 (54-80) | 75.5 (66-79) | 0.39 |

| Sex, n | |||

| Male | 4 (66.7) | 16 (80.0) | 0.60 |

| Female | 2 (33.3) | 4 (20.0) | |

| Morphology, n (%) | |||

| Flat or depressed | 4 (57.1) | 16 (80.0) | 0.33 |

| Elevated | 3 (42.9) | 4 (20.0) | |

| Ulceration, n (%) | |||

| Presence | 0 (0) | 1 (5.0) | 1.0 |

| Absence | 7 (100) | 19 (95.0) | |

| Tumor size, mm | |||

| Median (IQR) | 6.0 (4-8) | 6.5 (5-9) | 0.45 |

| Tumor depth, n (%) | |||

| Mucosa | 4 (57.1) | 18 (90.0) | 0.09 |

| Submucosa | 3 (42.9) | 2 (10.0) | |

| Histology, n (%) | |||

| Differentiated | 7 (100) | 17 (85.0) | 1.0 |

| Undifferentiated | 0 (0) | 3 (15.0) |

The therapeutic outcomes of the GF-ER and ESD groups are compared in Table 3. The median procedure time was significantly shorter for the GF-ER group than for the ESD group [4.0 min (range: 3.0-5.0 min) vs 55.0 min (range: 30-105 min), P < 0.01]. There were no statistically significant differences between the GF-ER and ESD groups in the en bloc resection rates (100% vs 100%) and the R0 resection rates (100% vs 98.4%). In the ESD group, 5 patients (8.0%) experienced perforations and 1 patient (1.6%) experienced postoperative bleeding. No adverse events were encountered in the GF-ER group. The therapeutic outcomes for small lesions (≤ 10 mm) are shown in Table 4. In this subgroup analysis, all patients in both groups had en bloc and R0 resections. However, the median procedure time was significantly shorter in the GF-ER group than in the ESD group [4.0 min (range: 3.5-4.0 min) vs 35.0 min (range: 25-75 min), P < 0.001]. One patient (5.0%) in the ESD group experienced perforation.

| GF-ER | ESD | P value | |

| Procedure time, min | |||

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 55.0 (30-105) | < 0.01 |

| En bloc resection, n (%) | 9 (100) | 63 (100) | 1.0 |

| R0 resection, n (%) | 9 (100) | 62 (98.4) | 1.0 |

| Curative resection, n (%) | 9 (100) | 55 (87.3) | 0.54 |

| Perforation, n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (8.0) | 1.0 |

| Delayed bleeding, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 1.0 |

| GF-ER | ESD | P value | |

| Procedure time, min | |||

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 35.0 (25-75) | < 0.01 |

| En bloc resection, n (%) | 7 (100) | 20 (100) | 1.0 |

| R0 resection, n (%) | 7 (100) | 20 (100) | 1.0 |

| Curative resection, n (%) | 7 (100) | 19 (95.0) | 1.0 |

| Perforation, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.0) | 1.0 |

| Delayed bleeding, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of GF-ER and ESD for EGC in the GC of the stomach’s U and M regions. Lesions in these regions are considered relatively challenging to treat, although we found that GF-ER achieved en bloc and R0 resections with significantly shorter procedure times (vs ESD), without any adverse events. Similar results were observed in a subgroup analysis comparing GF-ER and ESD for lesions with diameters of ≤ 10 mm.

Many studies have compared EMR and ESD for EGC, and the results have indicated that ESD is superior to EMR in terms of the en bloc resection rate, while EMR is considered a shorter and safer procedure[15-17]. However, most reports included EMR for large lesions and were not limited to small lesions or lesions where en bloc was judged feasible. Furthermore, the reports often used data regarding EMR outcomes that were collected before ESD was developed, and focused on relatively stable procedures. In contrast, we compared the outcomes of ESD and GF-ER during the same period to avoid issues that might be related to improvements in endoscopic procedures over time. Our facilities also only perform GF-ER for small lesions where en bloc resection is considered feasible, which sets our findings apart from those of previous reports.

As an established endoscopic procedure, GF-ER provides advantages over other EMR methods, as it facilitates more extensive resection by using grasping forceps to pick up the lesion. Another advantage is that, because there is no aspiration step in the cap, the endoscopist can confirm that the entire lesion is within the snare before resecting it. Thus, en bloc resection is considered easier to perform and an assistant technique is unnecessary.

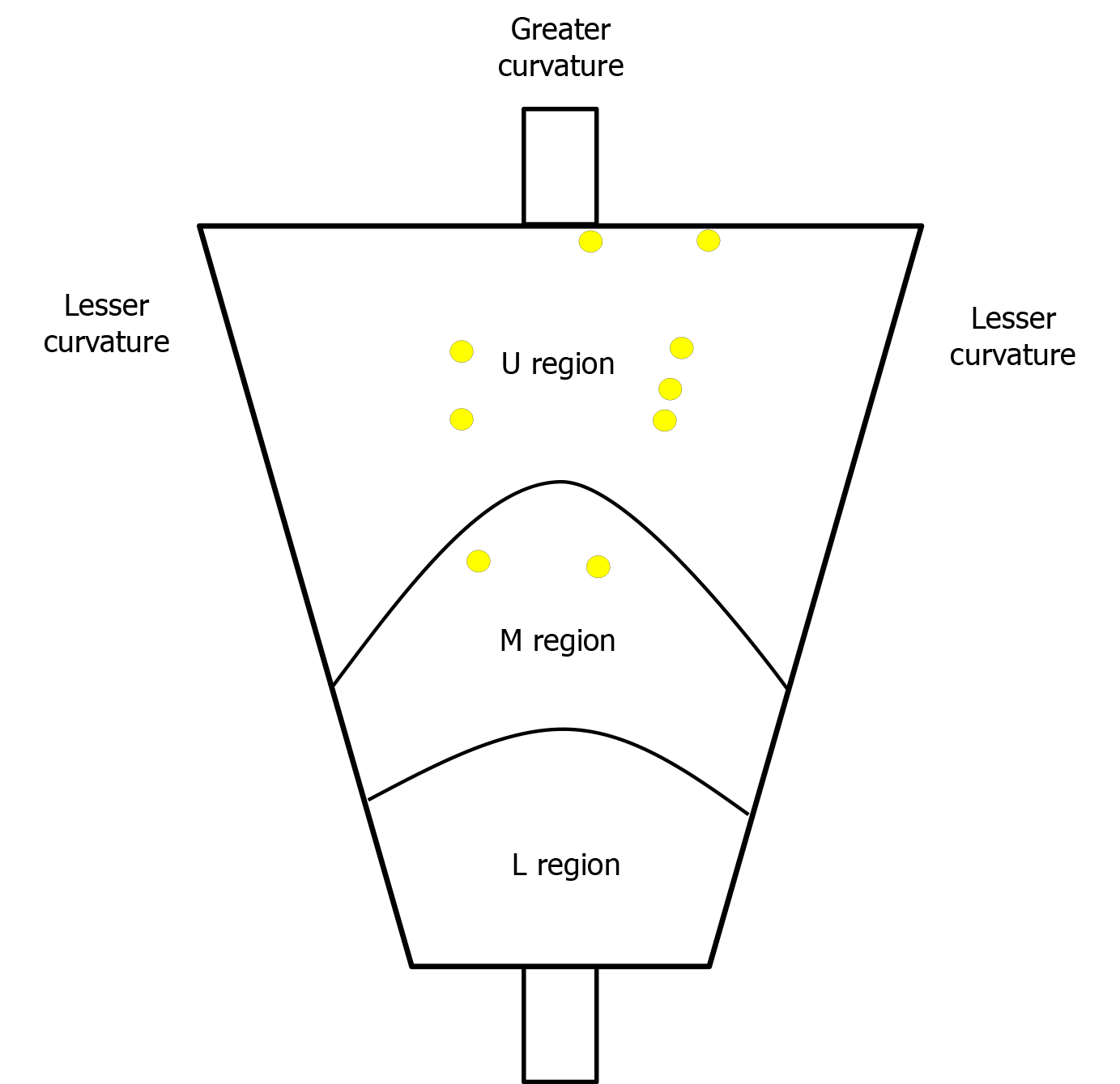

Some favourable results have been reported for GF-ER, which indicate that is has a short procedure time and en bloc resection rates of up to 82.4%-100%[18-20]. This technique can be applied in situations that would be considered particularly challenging for conventional EMR or ESD, such as in the absence of the lifting sign after the submucosal injection[18] and a large pedunculated polyp[19]. In this setting, the GF-ER might improve the procedure by directly grasping the gastrointestinal tumour, and previous reports have described areas or lesions that were considered difficult to treat using ESD. However, we are not aware of any reports directly comparing the treatment outcomes of GF-ER and ESD for gastric cancer, and we believe ours is the first report to evaluate the efficacy and safety of GF-ER and ESD for EGC. Figure 3 shows the locations of the 9 EGC lesions that were treated using GF-ER, and, despite their small size, these lesions were located in areas where ESD treatment would be considered very difficult.

Our findings suggest that GF-ER could be a useful therapeutic option in this setting, especially for small lesions located in the GC of the stomach’s U and M regions. The advantage of this technique is that it is simpler and faster to use, relative to ESD, and reducing the procedure time reduces the burden on the patient and the endoscopist. In addition, GF-ER provided comparable treatment outcomes. Furthermore, GF-ER is likely cost-effective, as the snares used in EMR are cheaper than the knives used in ESD. However, the disadvantage of GF-ER is that it requires a double-channel endoscope (GIF-2TQ260M; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), which is not commonly available, especially in Western countries. Nevertheless, it may be possible to perform this procedure via an additional accessory channel on the outside of the scope[21-23].

This study had some limitations. First, it was a retrospective study with a small sample size. Second, the operative method was not randomly assigned but was selected at the discretion of the endoscopist, which raises the possibility of selection bias. However, we exclusively performed GF-ER for lesions where en bloc resection was considered feasible via EMR. These lesions would have required a longer procedural time if ESD had selected.

In conclusion, this study revealed that GF-ER should be considered as an option for lesions in the GC of the stomach’s U and M regions, where ESD is considered a long, technically challenging, and potentially risky procedure. Although ESD is considered the first-line treatment for EGC, it is not always necessary to treat lesions in all areas using ESD, and EMR is a feasible option if en bloc resection is considered possible, as it can be performed easily and quickly. However, the indications for GF-ER limit the generalization of our findings, and a large prospective study is needed to validate our findings.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is widely accepted for early gastric cancer (EGC), although ESD is challenging, even for small lesions, in the greater curvature (GC) of the upper (U) and middle (M) thirds of the stomach.

Since ESD has become established, no new studies have compared the therapeutic outcomes of grasping forceps-assisted endoscopic resection (GF-ER) and ESD in the challenging U and M stomach regions.

To investigate the safety and efficacy of GF-ER and ESD in the GC of the stomach’s U and M regions.

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 506 patients who underwent ER of 522 EGC lesions in the stomach’s U and M regions in three institutions between January 2016 and May 2020.

En bloc resection was achieved in all patients from the GF-ER and ESD groups. The median procedure time in the GF-ER group was shorter than that in the ESD group (4.0 min vs 55.0 min, P < 0.01). There were no adverse events in the GF-ER group, although five perforations (8.0%) and 1 case of postoperative bleeding (1.6%) were observed in the ESD group. When we only considered lesions that were ≤ 10 mm, the median procedure time in the GF-ER group was still shorter than that in the ESD group (4.0 min vs 35.0 min, P < 0.01).

GF-ER should be considered as an option for lesions in the GC of the stomach’s U and M regions, where ESD is considered a long, technically challenging, and potentially risky procedure.

A large prospective study is needed to validate our findings.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: da Costa AC S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, Ohnita K, Mizuta Y, Shiozawa J, Kohno S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009;58:331-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Pyo JH, Lee H, Min BH, Lee JH, Choi MG, Lee JH, Sohn TS, Bae JM, Kim KM, Ahn JH, Carriere KC, Kim JJ, Kim S. Long-Term Outcome of Endoscopic Resection vs. Surgery for Early Gastric Cancer: A Non-inferiority-Matched Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:240-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chung IK, Lee JH, Lee SH, Kim SJ, Cho JY, Cho WY, Hwangbo Y, Keum BR, Park JJ, Chun HJ, Kim HJ, Kim JJ, Ji SR, Seol SY. Therapeutic outcomes in 1000 cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: Korean ESD Study Group multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1228-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 429] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Suzuki H, Takizawa K, Hirasawa T, Takeuchi Y, Ishido K, Hoteya S, Yano T, Tanaka S, Endo M, Nakagawa M, Toyonaga T, Doyama H, Hirasawa K, Matsuda M, Yamamoto H, Fujishiro M, Hashimoto S, Maeda Y, Oyama T, Takenaka R, Yamamoto Y, Naito Y, Michida T, Kobayashi N, Kawahara Y, Hirano M, Jin M, Hori S, Niwa Y, Hikichi T, Shimazu T, Ono H, Tanabe S, Kondo H, Iishi H, Ninomiya M; Ichiro Oda for J-WEB/EGC group. Short-term outcomes of multicenter prospective cohort study of gastric endoscopic resection: 'Real-world evidence' in Japan. Dig Endosc. 2019;31:30-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nagata S, Jin YF, Tomoeda M, Kitamura M, Yuki M, Yoshizawa H, Kubo C, Ito Y, Uedo N, Ishihara R, Iishi H, Tomita Y. Influential factors in procedure time of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer with fibrotic change. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:296-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Imagawa A, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Kato J, Kawamoto H, Fujiki S, Takata R, Yoshino T, Shiratori Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: results and degrees of technical difficulty as well as success. Endoscopy. 2006;38:987-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gotoda T. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Suzuki Y, Hiraishi H, Kanke K, Watanabe H, Ueno N, Ishida M, Masuyama H, Terano A. Treatment of gastric tumors by endoscopic mucosal resection with a ligating device. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:192-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Inoue H, Endo M, Takeshita K, Shimoju K, Yoshino K, Goseki N, Sasabe M. Endoscopic resection of carcinoma in situ of the esophagus accompanied by esophageal varices. Surg Endosc. 1991;5:182-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Karita M, Tada M, Okita K, Kodama T. Endoscopic therapy for early colon cancer: the strip biopsy resection technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:128-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Suzuki S, Gotoda T, Kobayashi Y, Kono S, Iwatsuka K, Yagi-Kuwata N, Kusano C, Fukuzawa M, Moriyasu F. Usefulness of a traction method using dental floss and a hemoclip for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: a propensity score matching analysis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:337-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in RCA: 1915] [Article Influence: 239.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2873] [Article Influence: 205.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9275] [Cited by in RCA: 13318] [Article Influence: 1109.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Oka S, Tanaka S, Kaneko I, Mouri R, Hirata M, Kawamura T, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Advantage of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:877-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 487] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Gastric Cancer Treatment Guideline, 2nd edn. (in Japanese). Kanehara, Tokyo, 2004. |

| 17. | Tao M, Zhou X, Hu M, Pan J. Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for patients with early gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | de Melo SW Jr, Cleveland P, Raimondo M, Wallace MB, Woodward T. Endoscopic mucosal resection with the grasp-and-snare technique through a double-channel endoscope in humans. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:349-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Akahoshi K, Kojima H, Fujimaru T, Kondo A, Kubo S, Furuno T, Nakanishi K, Harada N, Nawata H. Grasping forceps assisted endoscopic resection of large pedunculated GI polypoid lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:95-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Higashino K, Iishi H, Narahara H, Uedo N, Yano H, Ishiguro S, Tatsuta M. Endoscopic resection with a two-channel videoendoscope for gastric carcinoid tumors. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:269-272. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Walter B, Schmidbaur S, Krieger Y, Meining A. Improved endoscopic resection of large flat lesions and early cancers using an external additional working channel (AWC): a case series. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E298-E301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wedi E, Knoop RF, Jung C, Ellenrieder V, Kunsch S. Use of an additional working channel for endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR +)of a pedunculated sessile serrated adenoma in the sigmoid colon. Endoscopy. 2019;51:279-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Meier B, Wannhoff A, Klinger C, Caca K. Novel technique for endoscopic en bloc resection (EMR+) - Evaluation in a porcine model. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:3764-3774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |