Published online Jan 15, 2021. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v13.i1.87

Peer-review started: June 16, 2020

First decision: August 9, 2020

Revised: September 1, 2020

Accepted: October 11, 2020

Article in press: October 11, 2020

Published online: January 15, 2021

Processing time: 204 Days and 17.8 Hours

The incidence of carcinoma found within an internal hemorrhoid specimen is exceptionally rare. Further, the presence of primary anal canal adenocarcinoma within internal hemorrhoids is even more infrequent. We describe a case in which anal canal adenocarcinoma was found within an internal hemorrhoidectomy specimen and perform a review of the current literature.

The patient was a 79-year-old male who presented with rectal bleeding and was found to have large thrombosed internal hemorrhoids during screening colonoscopy. The patient subsequently underwent a three-column hemorrhoi-dectomy. Pathologic analysis revealed one of three specimens containing a 1.5 cm moderate-to-poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of anal origin with superficial submucosal invasion. At three-month follow up, he was taken to the operating theatre for biopsy and re-excision of his non-healing wound, which showed no recurrence. His wound has since healed and he was cancer free at ten-month follow up.

When faced with primary anal canal adenocarcinoma an interdisciplinary approach to treatment should be considered. Routine pathological analysis of hemorrhoidectomy specimens may be beneficial due to the severity of anal canal carcinomas if left undiagnosed and untreated in a timely manner.

Core Tip: The presence of primary anal canal adenocarcinoma within internal hemorrhoids is extremely rare and can be easily missed if hemorrhoidectomy specimens are not sent for routine pathology. When faced with primary anal canal adenocarcinoma an interdisciplinary approach to treatment should be considered. Routine pathological analysis of hemorrhoidectomy specimens may be beneficial due to the severity of anal canal carcinomas if left undiagnosed and untreated in a timely manner.

- Citation: Caparelli ML, Batey JC, Tailor A, Braverman T, Barrat C. Internal hemorrhoid harboring adenocarcinoma: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2021; 13(1): 87-91

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v13/i1/87.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v13.i1.87

Pathologic analysis of a hemorrhoidectomy specimen rarely results in carcinoma[1]. Current literature cites an incidence of 1%-2%; however, objective data is lacking[2-4]. Cataldo and Mackeigan[2] reviewed a data set that revealed only 1 of 21527 hemorrhoidectomies (0.0046%) contained an unsuspected carcinoma and did not specify whether this particular specimen contained adeno- or squamous cell carcinoma. Neoplasms of the anal canal are most commonly squamous cell carcinoma, followed by cloacogenic (or basaloid or transitional cell) carcinoma, and rarely adenocarcinoma[1,5]. Additionally, adenocarcinomas of the anal canal are often considered to be the result of the downward extension of a primary tumor of distal rectal origin or from the columnar epithelium in the upper anal canal, and are therefore considered to be of rectal origin and not true anal carcinomas[1]. We describe the case of an unsuspecting hemorrhoidectomy specimen that was found to contain adenocarcinoma of the anal canal.

Rectal bleeding.

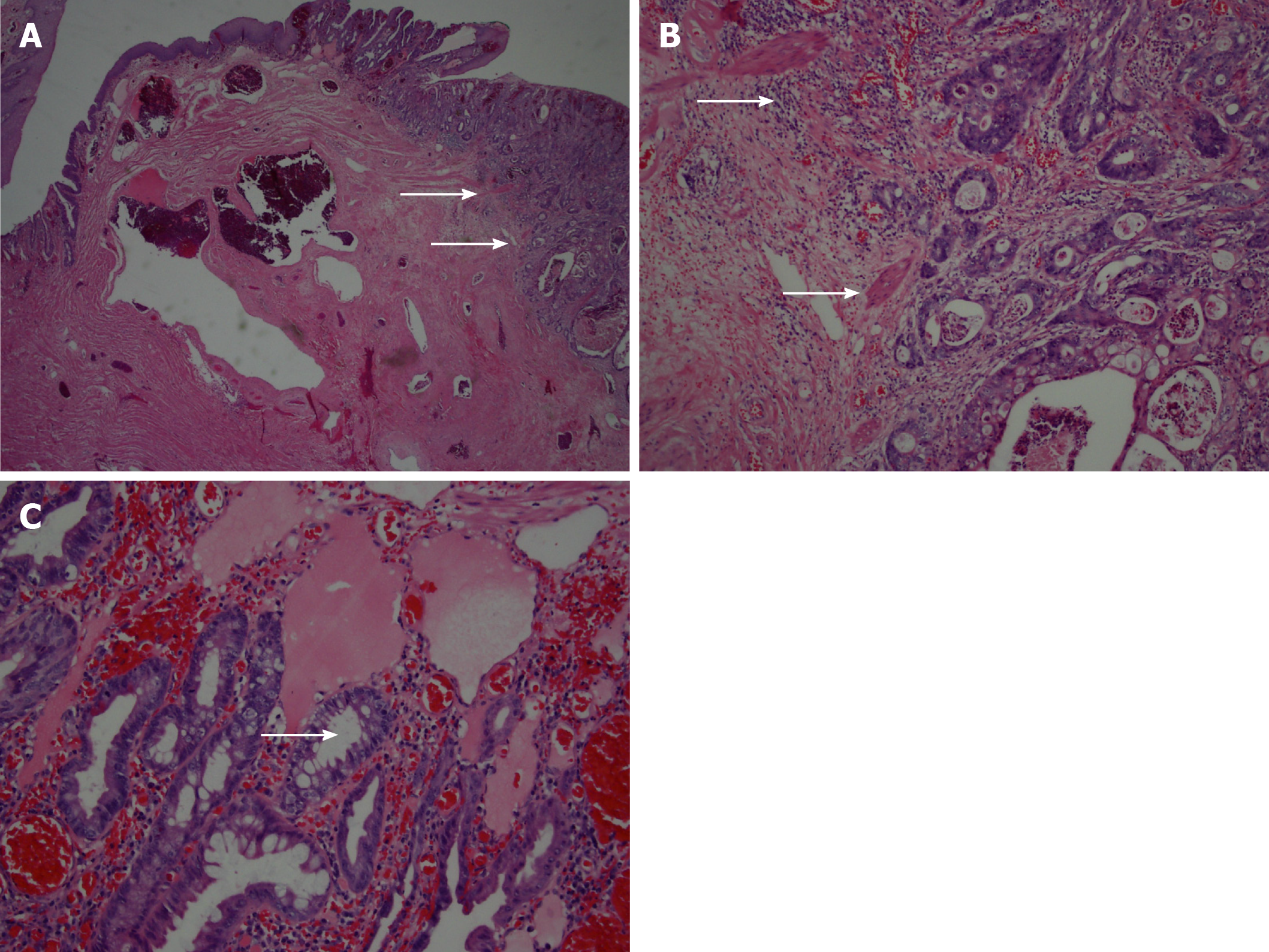

A 79-year-old male who presented with rectal bleeding and discovery of large thrombosed internal hemorrhoids during screening colonoscopy. He reported intermittent hematochezia and denied rectal pain or changes in the frequency, consistency or caliber of bowel movements. He is a self-reported never smoker who adheres to a high-fiber diet. The patient subsequently underwent an uneventful three-column hemorrhoidectomy. The internal hemorrhoids were identified, excised, and sent for routine pathologic evaluation. Pathologic analysis revealed the left lateral hemorrhoid column positive for a 1.5 cm moderate-to-poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. The tumor showed superficial invasion into the submucosa along with a focus that was suspicious for lymphatic invasion (Figure 1).

The patient has a history of atrial fibrillation, diabetes, and remote history of hemorrhoids. The patient underwent a previous laser ablation 10 years prior for bleeding internal hemorrhoids. However, there was no procedure note to denote the location of the bleeding hemorrhoid or pathology report to suggest biopsy in the electronic medical record.

Digital rectal examination prior to hemorrhoidectomy revealed one small skin tag, but was otherwise unremarkable. He had no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Anoscopy revealed a single large inflamed and prolapsing internal hemorrhoid.

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), 6.3%; and albumin, 4.4 g/dL.

Computed tomography (CT) chest/abdomen/pelvis-negative, endorectal ultrasound-negative.

The case was presented to the institution’s Interdisciplinary Tumor Board, at which time the recommendation was made to pursue wide local excision of the area.

Moderate-to-poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the anal canal.

A wide local excision of the previous left lateral hemorrhoidectomy column was pursued. The excision was carried out with a wide margin from the previous scar - at least 2 cm in either direction. The distal and proximal margins were 3 cm onto the perianal skin, and 5 cm into the anal canal and distal rectum. The lateral margins were at least 2 cm from previous scar. The deep margin was into the ischioanal fat. No frozen section was planned at the time of reoperation.

Pathologic analysis of the transanal excision specimen revealed chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and foreign body reaction with no residual neoplasm identified. The patient experienced some post-operative bleeding requiring chemical cauterization of granulation tissue, but has otherwise continued along an uncomplicated trajectory of recovery. At three-month follow up, he was taken to the operating theatre for biopsy and re-excision of his non-healing wound, which showed no recurrence. His wound has since healed and he was cancer free at ten-month follow up. It is unclear why the wound initially did not heal. The patient was a non-smoker, had well-controlled diabetes (HbA1c, 6.3%), and albumin (4.4 g/dL) at the time of operation. Close observation and surveillance will be kept, including a full colonoscopy 1 year from diagnosis of adenocarcinoma.

The incidence of a hemorrhoidectomy specimen harboring any type of malignancy is exceptionally rare. Adenocarcinoma represents approximately six percent of anal carcinomas overall and is even more rare within a hemorrhoidectomy specimen as one would expect squamous cell carcinoma to occur with higher frequency in the anal canal. It is also more common to have a primary rectal carcinoma within a hemorrhoid specimen from downward extension or metastasis than to have a hemorrhoid harboring a primary anal canal carcinoma. Additionally, there have been reports of implantation of primary rectal adenocarcinoma on a hemorrhoidectomy specimen and occurrences of metastatic rectal adenocarcinoma found within a hemorrhoid[6,7].

Our case is unique because we describe a primary anal canal adenocarcinoma within a hemorrhoidectomy specimen. To our knowledge, there have been less than ten cases reported in the literature. Our patient presented with rectal bleeding, which is consistent with anal cancer but can often be attributed to internal hemorrhoids. Interestingly, he did not experience any anorectal pain, a symptom, which occurs in approximately thirty percent of patients with anal canal cancer. Additional epidemiologic factors that contribute to anal cancers are human papillomavirus, chronic immunosuppression and smoking[8-10]. These risk factors are typically associated with anal squamous cell carcinomas, and were not demonstrated by our patient.

Due to the rarity of primary adenocarcinoma in the anal canal, staging workup follows that of a rectal adenocarcinoma[11]. This should include full colonoscopy, carcinoembryonic antigen level, CT chest/abdomen/pelvis and either endorectal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging pelvis, as would be performed for rectal adenocarcinoma. Consideration should be given to an interdisciplinary approach to treatment due to the rarity of this tumor. Our patient underwent complete evaluation and was discussed at our institution’s tumor board. The staging workup for our patient’s lesion was consistent with a T1N0M0 anal cancer. Management of adenocarcinomas arising in the anal canal typically follows the same principles as those applied to rectal cancer. Since our patient’s tumor was limited to the superficial submucosa, transanal excision was adequate and has spared the patient from the morbidity of an abdominoperineal resection (APR).

Another key point to be made in this case is that pathologic evaluation of the hemorrhoidectomy specimen was performed. It has been suggested that pathologic evaluation should be limited to patients who are at high risk of lesions with anal intraepithelial neoplasia (immunocompromised, papillomatous lesions) or if there is concern for malignancy based on preoperative, intraoperative or inspection of excised tissue[4]. This has been suggested as the cost of detecting one cancer would be uneconomic, given its rarity. Had this standard approach been followed, we would have missed a potentially life-threatening anal canal cancer, or it may have manifested months later and resulted in an APR. At our institution, hemorrhoidectomy specimens are routinely sent for pathologic analysis.

Adenocarcinoma within a hemorrhoidectomy specimen is an exceptionally rare event, but should not be overlooked. Consideration for routine pathological analysis of hemorrhoidectomy specimens may be beneficial due to the severity of anal canal carcinomas if left undiagnosed and untreated in a timely manner.

Thank you to our families, friends and colleagues who support us in our work.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Govindarajan KK S-Editor: Chen XF L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Timaran CH, Sangwan YP, Solla JA. Adenocarcinoma in a hemorrhoidectomy specimen: case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2000;66:789-792. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Cataldo PA, MacKeigan JM. The necessity of routine pathologic evaluation of hemorrhoidectomy specimens. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;174:302-304. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Lohsiriwat V, Vongjirad A, Lohsiriwat D. Value of routine histopathologic examination of three common surgical specimens: appendix, gallbladder, and hemorrhoid. World J Surg. 2009;33:2189-2193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Matalon SA, Mamon HJ, Fuchs CS, Doyle LA, Tirumani SH, Ramaiya NH, Rosenthal MH. Anorectal Cancer: Critical Anatomic and Staging Distinctions That Affect Use of Radiation Therapy. Radiographics. 2015;35:2090-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hsu TC, Lu IL. Implantation of adenocarcinoma on hemorrhoidectomy wound. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1407-1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gujral DM, Bhattacharyya S, Hargreaves P, Middleton GW. Metastatic rectal adenocarcinoma within haemorrhoids: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Frisch M, Glimelius B, van den Brule AJ, Wohlfahrt J, Meijer CJ, Walboomers JM, Goldman S, Svensson C, Adami HO, Melbye M. Sexually transmitted infection as a cause of anal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1350-1358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Penn I. Incidence and treatment of neoplasia after transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993;12:S328-S336. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Holly EA, Whittemore AS, Aston DA, Ahn DK, Nickoloff BJ, Kristiansen JJ. Anal cancer incidence: genital warts, anal fissure or fistula, hemorrhoids, and smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1726-1731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Rectal Cancer (Version 1.2019). 2019. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf. |