Published online Mar 15, 2020. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i3.276

Peer-review started: October 23, 2019

First decision: November 18, 2019

Revised: November 24, 2019

Accepted: December 23, 2019

Article in press: December 23, 2019

Published online: March 15, 2020

Processing time: 136 Days and 6.2 Hours

The kinesin superfamily protein member KIF21B plays an important role in regulating mitotic progression; however, the function and mechanisms of KIF21B in cancer, particularly in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), are unknown.

To explore the role of KIF21B in hepatocellular carcinoma and its effect on prognosis after hepatectomy.

First, data on the differential expression of KIF21B in patients with HCC from The Cancer Genome Atlas database was analyzed. Subsequently, the expression levels of KIF21B in HCC cell lines and hepatocytes were detected by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, and its biological effect on BEL-7404 cells was evaluated by KIF21B knockdown. Immunohistochemical analysis was used to validate the differential expression of KIF21B in HCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues from 186 patients with HCC after hepatectomy. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to assess prognosis significance.

KIF21B expression levels were significantly higher in HCC tissues than in corresponding adjacent normal tissues. The expression levels of KIF21B in four HCC cell lines were higher than that in normal liver cells. Functional experiments showed that KIF21B knockdown remarkably suppressed cell proliferation and induced apoptosis. Moreover, immunohistochemistry results are consistent with The Cancer Genome Atlas analysis, with KIF21B expression levels being increased in HCC tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues. Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed KIF21B as an independent risk factor for overall survival and disease-free survival in patients with HCC after hepatectomy.

Taken together, our results provide evidence that KIF21B plays an important role in HCC progression and may be a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker for HCC.

Core tip: The kinesin superfamily protein member KIF21B plays an important role in regulating mitotic progression; however, the function and mechanisms of KIF21B in cancer, particularly in hepatocellular carcinoma, are unknown. We explored the role of KIF21B in hepatocellular carcinoma and elucidated its clinical significance. Our findings suggest that KIF21B may be a potential biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Citation: Zhao HQ, Dong BL, Zhang M, Dong XH, He Y, Chen SY, Wu B, Yang XJ. Increased KIF21B expression is a potential prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2020; 12(3): 276-288

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v12/i3/276.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v12.i3.276

According to the global cancer statistics in 2018, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranked sixth and third in incidence and mortality, respectively[1]. In China, its incidence and mortality ranked fourth and third, respectively[2]. Patients with HCC who are diagnosed at an early stage have a relatively favorable prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 75%[3]. However, most HCC patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, and recurrence and metastasis remain major challenges in HCC treatment, leading to an extremely poor prognosis[4]. Thus, there is an urgent need to identify novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for HCC.

Microtubule kinesin motor proteins participate in a series of cellular processes, such as mitosis, motility, and organelle transportation, and are involved in human carcinogenesis[5]. Kinesins are molecular motor proteins that move along microtubule tracks and perform various functions in intracellular transport and cell division[6]. Previous studies have reported that kinesins play critical roles in tumorigenesis and the progression of malignancies[7,8]. KIF21B, a member of the kinesin superfamily of proteins, plays an important role in regulating mitotic progression. Studies have confirmed that KIF21B was found in several types of cells, including neurons and immune cells[9-11]. Genetic alterations in the KIF21B protein have been linked with several neurodegenerative diseases[12]. KIF21B performs in excitatory synaptic transmission and silencing the expression of KIF21B inhibits its function and affects its biological behavior[13]. However, no previous studies have focused on the function and mechanisms of KIF21B in cancer, particularly in HCC. The role of KIF21B in HCC and its effect on prognosis have not yet been investigated and remain unknown.

In this study, we explored the role of KIF21B in HCC and elucidated its clinical significance. We first assessed the differential expression of KIF21B using the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Then, we measured its biological effect on BEL-7404 cells after transfection with KIF21B-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated that KIF21B was an independent risk factor for overall survival and disease-free survival in patients with HCC. KIF21B may serve as a novel prognostic marker and as a therapeutic target in the treatment of HCC.

A total of 186 HCC tissue specimens and matched adjacent normal tissues collected at Gansu Provincial Hospital between 2013 and 2018 were included in the study. In accordance with the protocol used to obtain the tissue samples, informed consent was obtained from all donors and recipients. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gansu Provincial Hospital. The characteristics of patients with HCC are summarized in Table 1. Two independent pathologists diagnosed HCC based on the World Health Organization criteria. None of the patients had received chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or transarterial chemoembolization prior to surgery. HCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues were collected, fixed with 10% formaldehyde solution, and embedded in paraffin.

| Characteristic | n | KIF21B expression | P value | |

| Low | High | |||

| Age (yr) | 0.877 | |||

| > 55 | 115 | 42 | 73 | |

| ≤ 55 | 71 | 27 | 44 | |

| Gender | 0.286 | |||

| Male | 102 | 34 | 68 | |

| Female | 84 | 35 | 49 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.229 | |||

| > 5 | 89 | 29 | 60 | |

| ≤ 5 | 97 | 40 | 57 | |

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.543 | |||

| Yes | 103 | 36 | 67 | |

| No | 83 | 33 | 50 | |

| TNM stage | 0.046a | |||

| I-II | 105 | 32 | 73 | |

| III-IV | 81 | 37 | 44 | |

| HBsAg | 0.003b | |||

| Yes | 110 | 31 | 79 | |

| No | 76 | 38 | 38 | |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 0.061 | |||

| > 400 | 112 | 40 | 72 | |

| ≤ 400 | 74 | 29 | 45 | |

| Vascular invasion | 0.012a | |||

| Yes | 117 | 35 | 82 | |

| No | 69 | 34 | 35 | |

The KIF21B expression profile and relative clinicopathologic features of patients with HCC were selected from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/legacy-archive/search/f). The database included 50 paired cancer and adjacent normal tissues, which were used to examine the differential expression of KIF21B between HCC and adjacent normal tissues. The data were standardized using the Trimmed Mean of M-values method, and biological coefficient of variation was performed for the quality control. Differentially expressed genes were accessed using the TCGA analyze-DEA function considering a log2 fold change > 1 or < −1. The fold change was the ratio of gene expression in the cancer samples to that in the adjacent normal samples. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

HCC cell lines Hep-G2, BEL7402, BEL-7404, and SMMC-7721 and the normal liver cell line Chang liver were purchased from Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). BEL7402, BEL-7404, and Chang liver cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). SMMC-7721 and HepG2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The cell lines were cultured in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2. To further probe the role of KIF21B in HCC cells, KIF21B expression in BEL-7404 cells was silenced using lentivirus-mediated siRNA. In brief, cells were transfected for 24 h with lentiviral constructs expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) specific for KIF21B (shKIF21B; Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd.) or control shRNA (shCtrl; Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd.). Green fluorescence was used to estimate the efficiency of transfection. Stable knockdown cells were selected using puromycin.

TRIzol reagent (Shanghai Pufei Biotech Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) was used to extract total RNA from BEL-7404 cells, which was used as a template for synthesis of cDNA using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega, Beijing, China). For real-time quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), cDNA was mixed with SYBR Master Mixture (TAKARA, Kyoto, Japan) and amplified using a real-time PCR thermocycler (Agilent Technologies, Beijing, China). The PCR primers used have the following sequences: KIF21B forward, 5ʹ-GGATGCCACAGATGAGTT-3ʹ and reverse, 5ʹ-TGTCCCGTAACCAAGTTC-3ʹ; GAPDH forward, 5ʹ-TGACTTCAACAGCGACACCCA-3ʹ and reverse, 5ʹ-CACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAA-3ʹ. PCR amplification was quantitated using the 2-∆∆Ct method. Each sample was amplified in triplicate, and GAPDH was used as an internal control. The KIF21B and GAPDH primers were designed by Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd.

Concentrations of proteins extracted from cells were measured using a Bicinchoninic acid Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) based on the manufacturer’s instructions. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was used to separate the total proteins, and the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, United States). The membranes were incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C followed by incubation with the corresponding secondary antibodies: Mouse-human KIF21B antibody (1:400; Sigma-Aldrich) and rabbit-human anti-GAPDH (1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, United States); goat anti-mouse IgG (1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology CA, United States) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). GAPDH was used as an internal control.

BEL-7404 cells were transfected with shKIF21B or shCtrl. Three days later, the cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2000 cells/well. The cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 5 d. The cells were counted daily using a Celigo Imaging Cytometer (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA, United States). Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Lentivirus-infected BEL-7404 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2000 cells/well, and cell viability was assessed using MTT (Genview, Beijing, China). MTT (5 mg/mL) was added to each well (20 μL) and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Dimethyl sulfoxide (Shanghai Shiyi Chemical Technology Co., LTD, Shanghai, China) was added to each well (100 μL). The MTT colorimetric assay was performed to detect cell proliferation after 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 d of incubation. Absorbance by the resulting formazan crystals (solubilized with DMSO) was read at 490 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader.

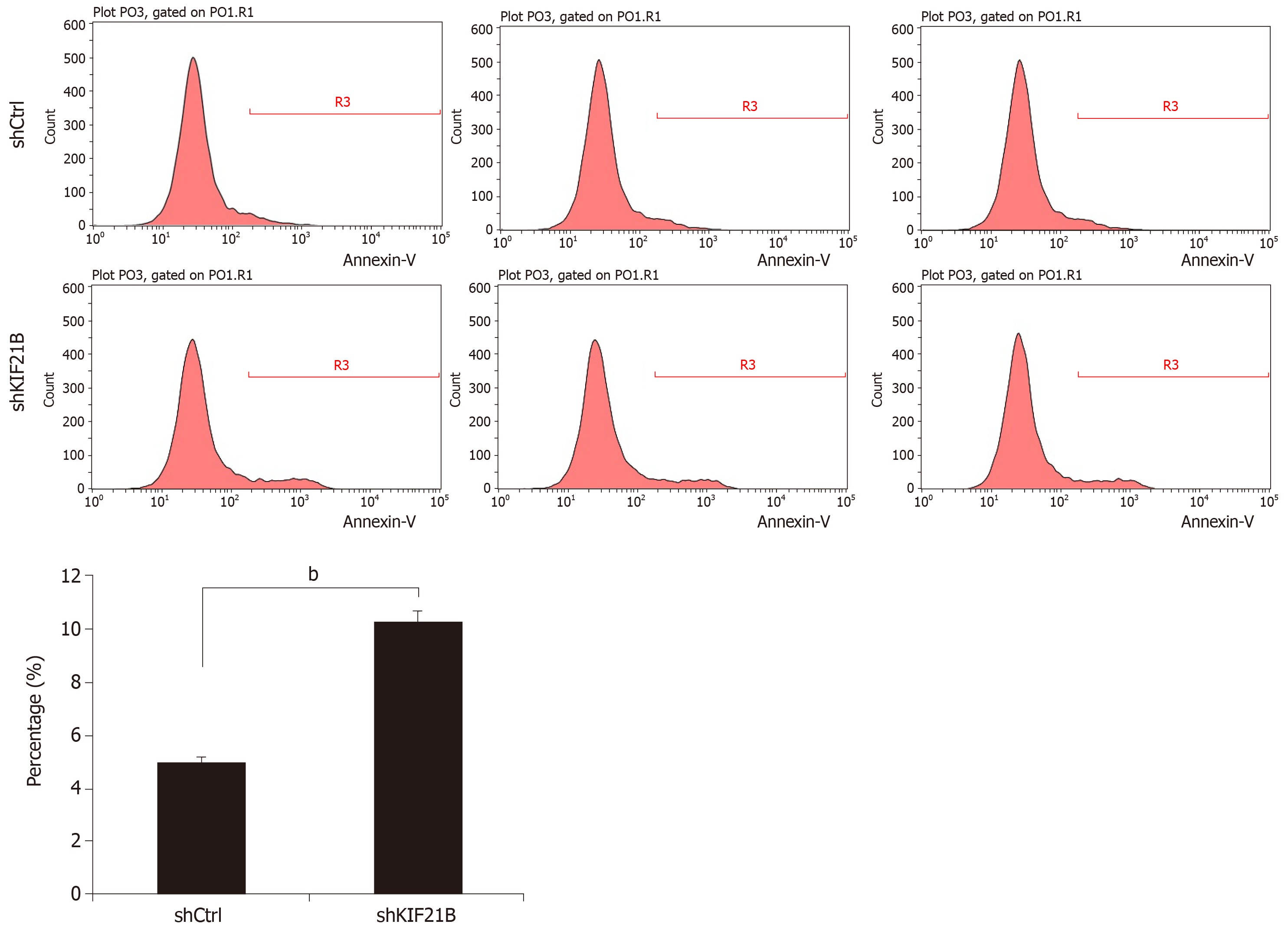

To quantify the effects of shKIF21B on cell apoptosis, the transfected cells were fixed with ice-cold 75% ethyl alcohol at 4 °C overnight. The cells were stained using an Annexin V-APC/7-AAD Kit (eBioscience, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were incubated with Annexin V–APC for 15–20 min at room temperature in the dark.

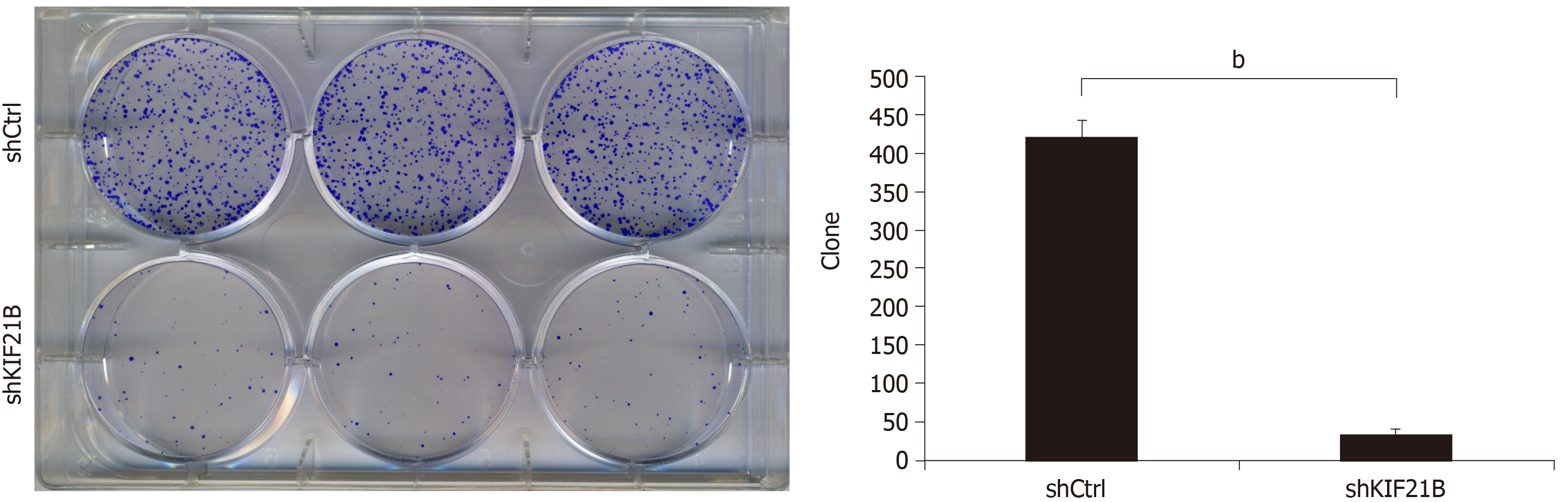

Colony formation assays were used to detect the growth of cells. BEL-7404 cells were transfected with shKIF21B or shCtrl. Three days later, 1000 cells/well were seeded into six-well plates and cultured for 14 d at 37 °C. Cell status was evaluated, and the medium replaced every 3 d. At the end of the culture period, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30–60 min. The fixed cells were washed with PBS, stained with Crystal Violet Staining Solution (Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China) for 10–20 min, and washed several times with double-distilled water. The number of colonies formed was counted using a microscope and photographed.

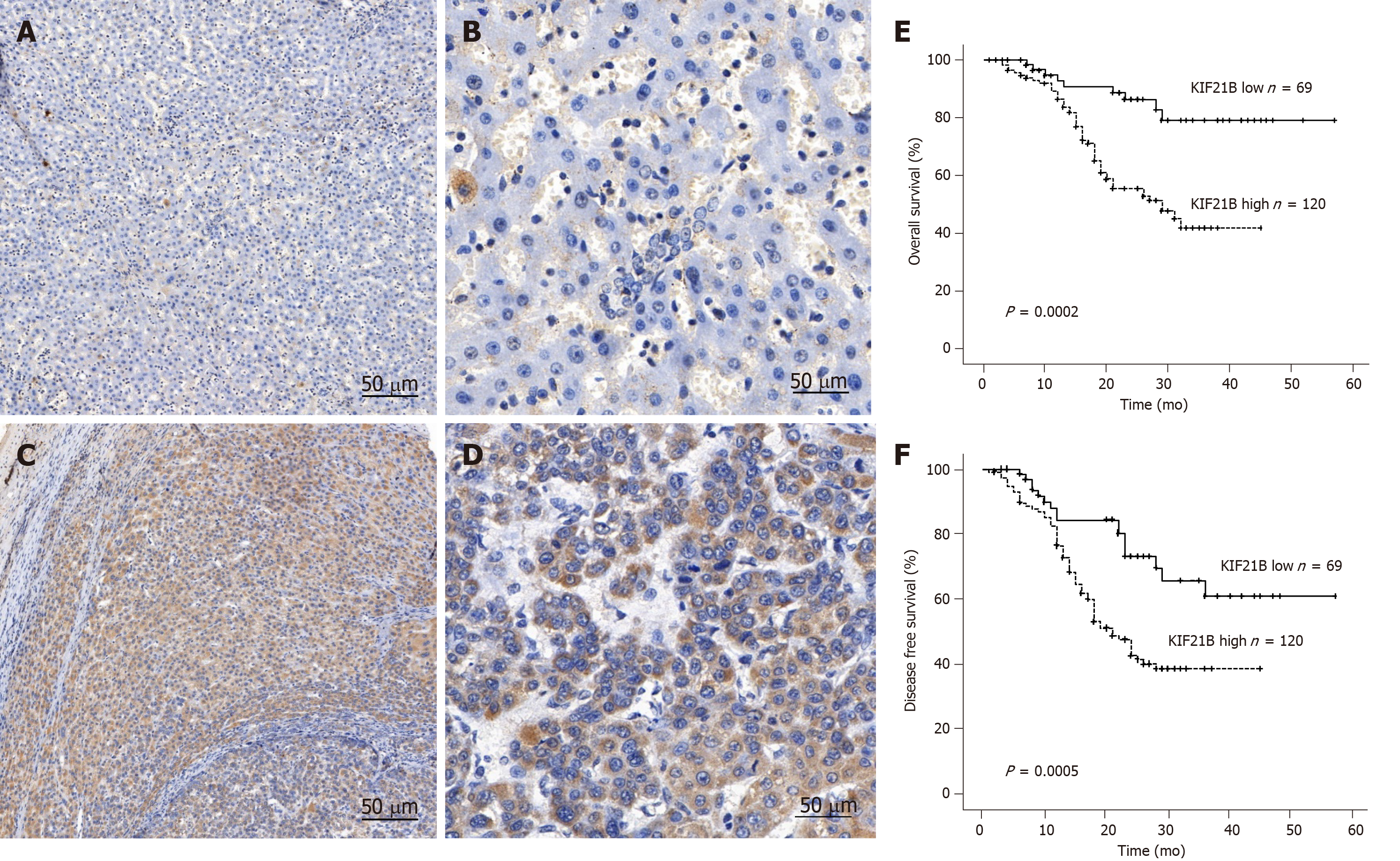

Sections of each specimen (5 μm thick) were placed on glass slides, deparaffinized, dehydrated, and boiled in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer for antigen retrieval. After inhibition of endogenous peroxidase activity by incubation for 10 min with methanol containing 0.3% H2O2, the sections were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin for 30 min and incubated overnight at 4 °C with a primary polyclonal rabbit-human KIF21B antibody (1:200; Bioss, Beijing, China). After three washes with PBS, the slides were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG for 30 min, reacted with diaminobenzidine, and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Expression of KIF21B was independently evaluated by two pathologists who were blinded to the clinical and pathological stage of the patients. Staining results were assessed by taking into consideration both the percentage of positive cells and the intensity of staining. The positive percentage of KIF21B in the cells was evaluated as follows; 0 (< 10%); 1 (10%-25%); 2 (25%-50%); 3 (50%-70%); and 4 (> 70%). Staining intensity was considered as: 0 (negative); 1 (weak); 2 (moderate); and 3 (strong). According to the overall score of the percentage of positive cells × the intensity of staining, which ranged from 0-12, we graded the staining as follows: 0 (negative); 1-4 (weak); 5-9 (moderate); 10-12 (strong). An overall score > 5 was considered as high expression.

All the data shown are the results of at least three independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SD. The differences between groups were compared using Student’s t-test. Differences between groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or χ2 test. Cumulative survival was compared using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test. A multivariate Cox proportional-hazards regression model was used to identify independent prognostic factors. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

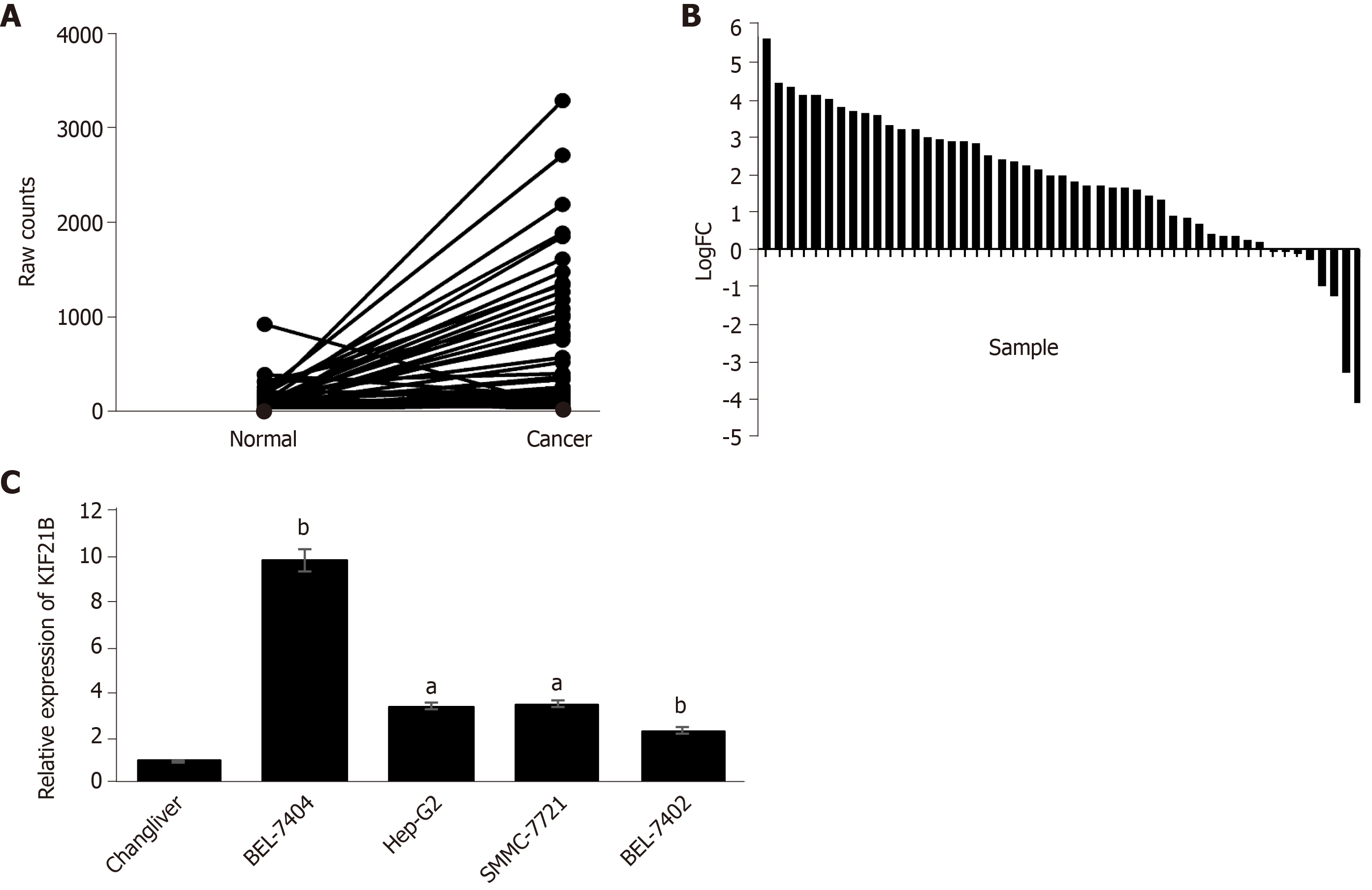

Based on the screening of the 50 pairs of HCC/adjacent normal tissues in TCGA database, KIF21B expression in HCC tissue was upregulated in 31 specimens, unchanged in 14, and downregulated in 5 compared to expression in the corresponding normal tissues (Figure 1A-B). We utilized RT-qPCR to detect the expression of KIF21B in the HCC cell lines (BEL-7404, BEL-7402, HepG2, and SMMC7721) and the normal liver cell line (Chang liver). The results showed that KIF21B mRNA expression was higher in HCC cell lines than in normal liver cells (Figure 1C). The BEL-7404 cell line was selected for use in subsequent investigations due to the KIF21B expression being at the highest level in this cell line among the five HCC cell lines evaluated.

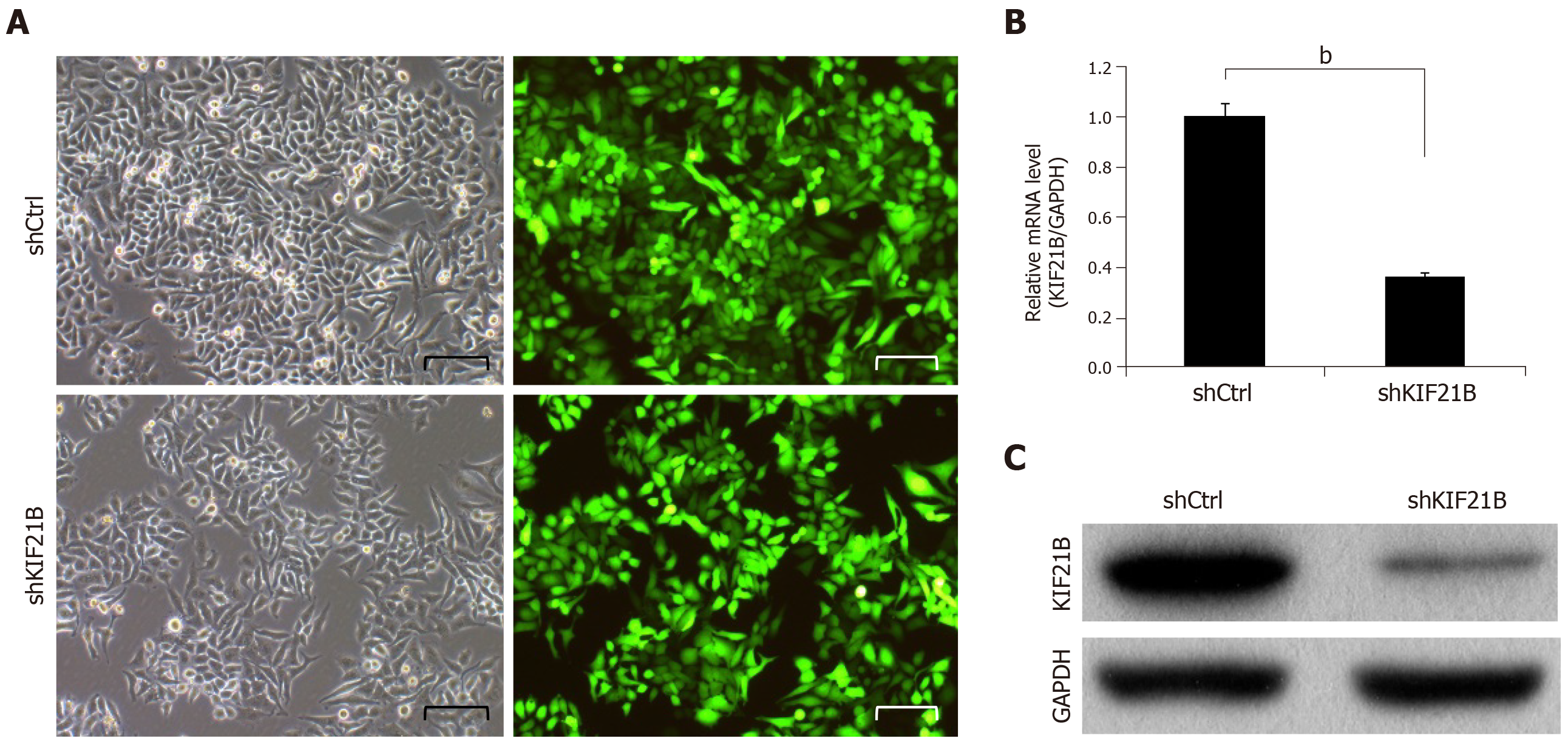

To investigate the role of KIF21B, we knocked down KIF21B expression in BEL-7404 cells using shRNA-mediated interference. As shown in Figure 2A, at 72 h after transfection, the proportion of infected cells in both the shCtrl and shKIF21B groups had reached 80%. Based on the RT-qPCR results (Figure 2B) and Western blot analysis (Figure 2C), the expression of KIF21B mRNA and KIF21B protein in the shCtrl group was significantly higher than that of the shKIF21B group.

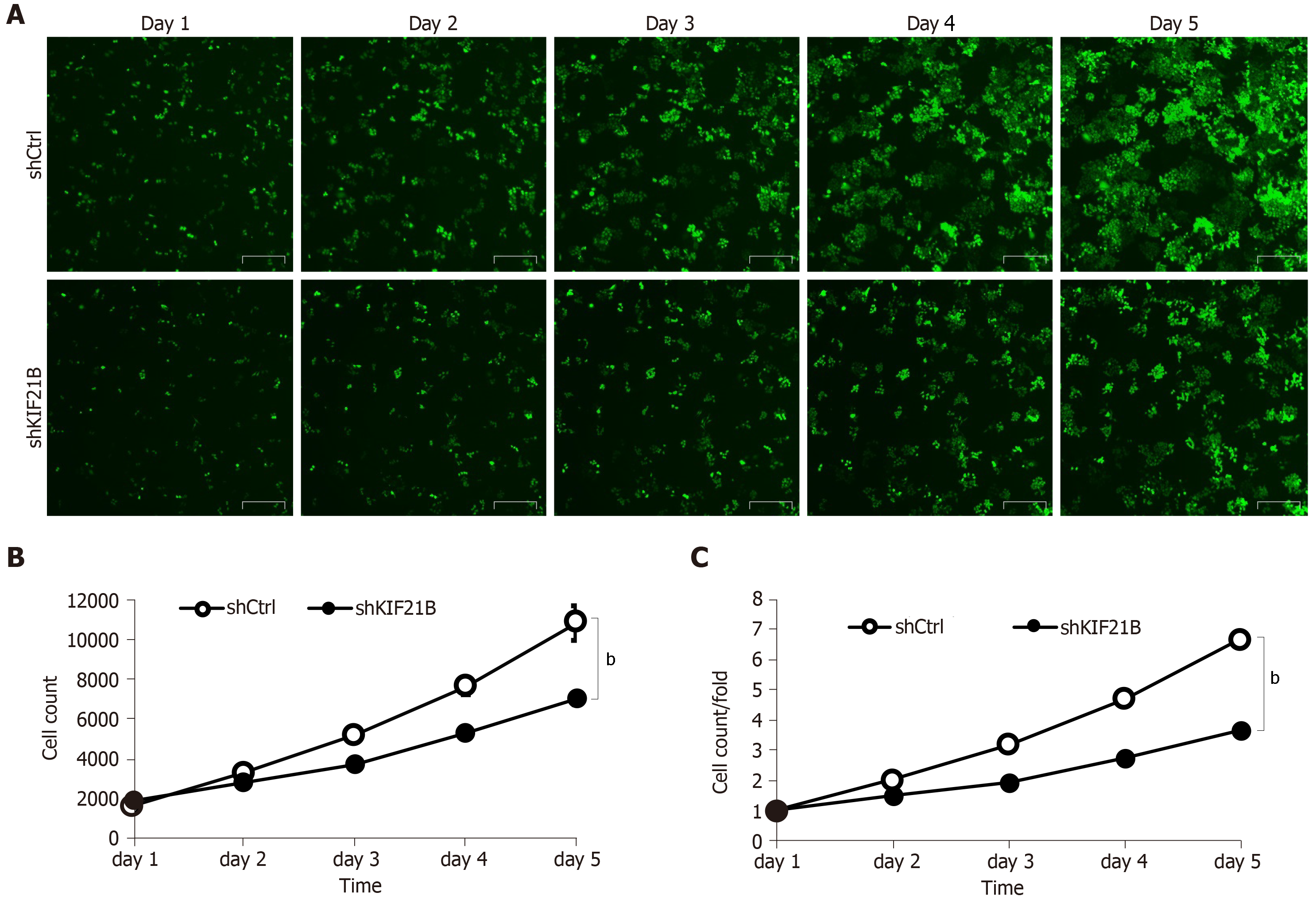

BEL-7404 cells transfected with shKIF21B or shCtrl were quantitated for 5 d using Celigo Imaging Cytometer analysis to evaluate cell growth. Silencing KIF21B significantly decreased the total number of cells and the rate of cell growth (Figure 3A-B).

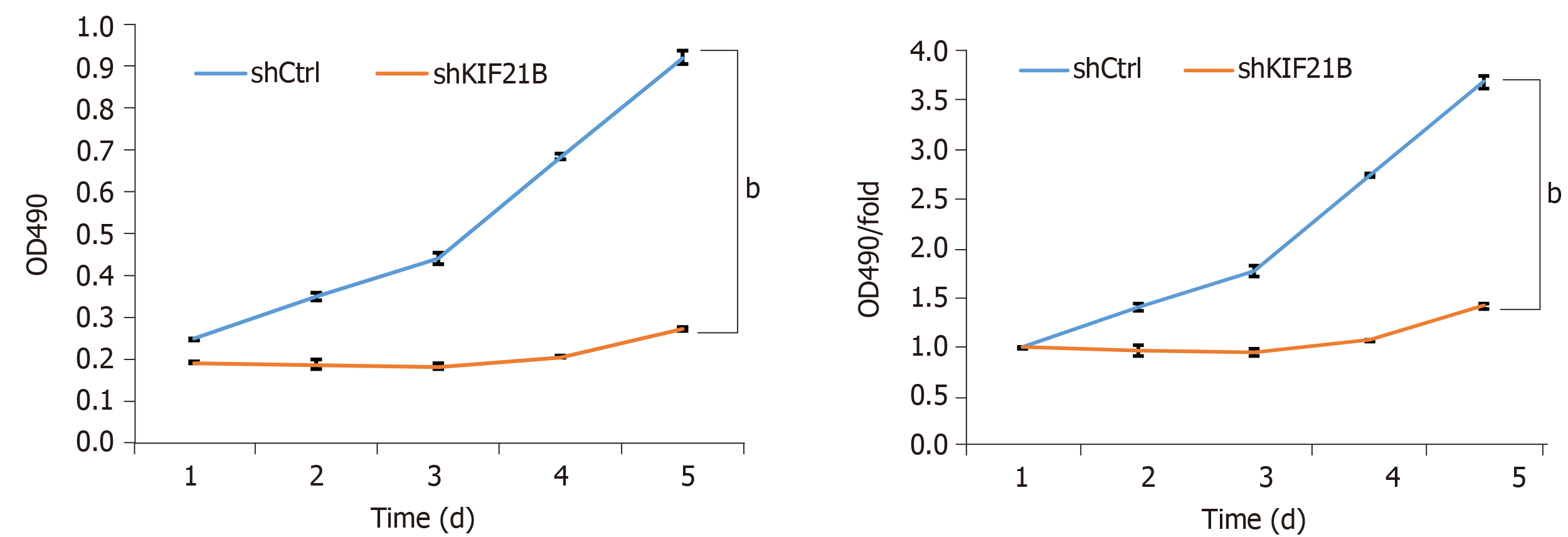

MTT analysis was used to evaluate the effect of KIF21B on cell proliferation. As shown in Figure 4, the shKIF21B group had lower cell viability compared to the shCtrl group with the difference being statistically significant at 4 d and 5 d post-transfection. Thus, silencing the expression of KIF21B inhibited cell proliferation.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was used to determine the effect of KIF21B knockdown in inducing apoptosis. The results showed that the level of apoptosis was significantly increased in shKIF21B-transfected cells compared with that of the shCtrl group. This result suggested that knockdown of KIF21B induced cell apoptosis (Figure 5).

Colony formation assay was used to confirm the effect of KIF21B knockdown on the self-renewal capacity of HCC cells. As shown in Figure 6, the results after transfection of BEL-7404 cells with shKIF21B or shCtrl demonstrated that knockdown of KIF21B significantly reduced the level of apoptosis in the shKIF21B group compared to the shCtrl group.

Immunohistochemistry was used to analyze the relationship between KIF21B expression and clinicopathological characteristics for the 186 patients with HCC. The results revealed that KIF21B was significantly higher in tumor tissues compared to adjacent normal tissue, and it exhibited cytoplasmic expression (Figure 7A-D). Moreover, the results validated the TGCA data regarding KIF21B expression in HCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues. As shown in Table 1, high expression of KIF21B correlated with vascular invasion (P < 0.05), TNM stage (P < 0.05), and HBsAg (P < 0.01). However, KIF21B expression did not correlate with gender, age, tumor size, or alpha fetoprotein (AFP) level (P > 0. 05).

Kaplan-Meier analysis of the 186 patients with HCC was performed to evaluate the relationship between KIF21B expression and prognosis. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves suggested that HCC patients with higher KIF21B expression had significantly lower OS (P = 0.0002) and DFS (P = 0.0005) after hepatectomy (Figure 7E and F). Univariate analysis showed that liver cirrhosis (P < 0.05) and KIF21B expression (P < 0.01) significantly correlated with OS while age (P < 0.05) and KIF21B expression (P < 0.01) significantly correlated with DFS (Tables 2 and 3, respectively). Multivariate analysis indicated that the level of KIF21B expression (P < 0.01) was an independent risk factor for OS (Table 2). KIF21B expression level (P < 0.01) and age were independent risk factors for DFS (Table 3). Overall, the univariate and multivariate analyses confirmed the potential of KIF21B as an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in HCC.

| Variable | Overall survival | |||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (> 55 yr vs ≤ 55 yr) | 0.489 | 0.195-1.225 | 0.293 | |||

| Gender (Male vs Female) | 0.726 | 0.291-1.809 | 0.491 | |||

| Tumor size (> 5 cm vs ≤ 5 cm) | 1.536 | 0.549-4.297 | 0.414 | |||

| Liver cirrhosis (Yes vs No) | 2.145 | 1.083-4.251 | 0.029a | 1.188 | 0.712-1.81 | 0.510 |

| TNM stage (I-II vs III-IV) | 0.718 | 0.387-1.333 | 0.294 | |||

| HBsAg (Yes vs No) | 0.844 | 0.476-1.495 | 0.560 | |||

| AFP (> 400 ng/mL vs ≤ 400 ng/mL) | 1.576 | 0.842-2.949 | 0.155 | |||

| Vascular invasion (Yes vs No) | 0.554 | 0.233-1.316 | 0.181 | |||

| KIF21B expression (low vs high) | 0.212 | 0.093-0.482 | < 0.001b | 0.264 | 0.130-0.539 | < 0.001b |

| Variable | Disease-free survival | |||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (> 55 yr vs ≤ 55 yr) | 0.413 | 0.188-0.909 | 0.028a | 0.464 | 0.284-0.759 | 0.002b |

| Gender (Male vs Female) | 0.636 | 0.281-1.439 | 0.277 | |||

| Tumor size (> 5 cm vs ≤ 5 cm) | 1.928 | 0.775-4.975 | 0.158 | |||

| Liver cirrhosis (Yes vs No) | 1.285 | 0.724-2.280 | 0.392 | |||

| TNM stage (I-IIvs III-IV) | 0.709 | 0.423-1.188 | 0.192 | |||

| HBsAg (Yes vs No) | 0.790 | 0.480-1.313 | 0.356 | |||

| AFP (> 400 ng/mL vs ≤ 400 ng/mL) | 1.116 | 0.657-1.896 | 0.684 | |||

| Vascular invasion (Yes vs No) | 0.905 | 0.410-1.997 | 0.805 | |||

| KIF21B expression (low vs high) | 0.320 | 0.168-0.611 | 0.001b | 0.373 | 0.216-0.643 | < 0.001b |

HCC is one of the most common liver malignancies worldwide, leading to extremely high incidence and mortality rates[4]. Due to continued tumor growth and metastasis, current treatment options are limited. Therefore, it is of great significance to determine the underlying mechanism of HCC to identify novel targets for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with HCC.

Kinesins are a superfamily of motor proteins that participate in mitosis, intracellular transportation, and cytoskeletal reorganization[14]. Changes in kinesins play pivotal roles in cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of cancer[15,16]. The KIFs member protein KIF21B is a microtubule motor protein that is dependent on ATP[15,17,18]. Recent studies suggest that KIF21B is not only a classic kinesin protein but also a regulator of microtubule dynamics[19-21]. In vitro reconstitution studies show that KIF21B increases the microtubule growth rate and catastrophe frequency. Moreover, the purified protein surprisingly associates primarily with depolymerizing microtubule and microtubule ends[22]. A recent study published in 2017 confirmed that KIF21B is a potential microtubule-pausing factor[21]. Microtubules and kinesins play roles in intercellular signal transduction, transport, malignant tumorigenesis, and tumor progression, invasion, and metastasis[11,23]. Therefore, in the current study we performed specific experiments to describe the role of KIF21B in HCC.

Specifically, we evaluated the differential expression of KIF21B across human cancer types by using the TCGA database. Importantly, KIF21B expression levels were found to be significantly increased in HCC tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues. In addition, compared to normal liver cells, the expression of KIF21B was significantly higher in HCC cell lines. Consistent with these observations, immunohistochemistry revealed that KIF21B expression was increased in most HCC tissues. We also measured the growth, proliferation, apoptosis, and colony formation ability of the HCC cell line BEL-7404 after transfection with KIF21B siRNA. The results showed that KIF21B qualified as an oncogene in hepatocellular cells by resisting the induction of apoptosis and by promoting cell proliferation and clone formation. Moreover, survival analysis demonstrated that HCC patients with high expression levels of KIF21B exhibited poor OS and DFS.

While the precise mechanisms of KIF21B remain unclear, to our knowledge, this study was the first to explore the biological behavior of KIF21B in HCC. We believe that the special cell lines used may allow KIF21B to decrease cell growth, proliferation, and self-renewal and to induce apoptosis. Furthermore, KIF21B may prove useful as an ideal target for gene therapy for HCC. More studies are needed to determine the effect that KIF21B may have on other tumor cell lines.

In conclusion, KIF21B plays a pivotal role in HCC carcinogenesis. The current cell culture studies confirmed that suppression of KIF21B expression by siRNA inhibited cell proliferation and induced apoptosis in BEL-7404 cells. Our results provide evidence that KIF21B may be considered as a novel prognostic biomarker and a new therapeutic molecular target for HCC.

As one of the most frequent cancers, the morbidity and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is increasing year by year. The kinesin superfamily protein member KIF21B plays an important role in regulating mitotic progression; however, the function and mechanisms of KIF21B in cancer, particularly in HCC, are unknown.

To explore the role of KIF21B in hepatocellular carcinoma and its clinical significance.

The study aimed to investigate the function of KIF21B in HCC and its effect on prognosis after hepatectomy.

First, we analyzed the differential expression of KIF21B in The Cancer Genome Atlas, and used immunohistochemical staining to validate it. Subsequently, after silencing KIF21B expression, the function of KIF21B in HCC lines was investigated by cell growth assay, MTT assay, fluorescence-activated cell sorting assay, and colony formation assay. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to assess its prognostic significance.

KIF21B expression levels were significantly higher in HCC tissues. Functional experiments showed that KIF21B knockdown remarkably suppressed cell proliferation and induced apoptosis. Statistical analyses revealed KIF21B as an independent risk factor in patients with HCC after hepatectomy.

KIF21B plays an important role in HCC progression and may be a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker for HCC.

In the future, more studies are needed to determine the effect that KIF21B may have on other tumor cell lines and to investigate the underlying mechanism.

We appreciate Professor Li-ping Wen and Professor Feng-lei Liu for their selfless help.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: El-Hawary AK, Shimizu Y S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941-1953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3585] [Cited by in RCA: 4891] [Article Influence: 698.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration. Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, Allen C, Al-Raddadi R, Alvis-Guzman N, Amoako Y, Artaman A, Ayele TA, Barac A, Bensenor I, Berhane A, Bhutta Z, Castillo-Rivas J, Chitheer A, Choi JY, Cowie B, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dey S, Dicker D, Phuc H, Ekwueme DU, Zaki MS, Fischer F, Fürst T, Hancock J, Hay SI, Hotez P, Jee SH, Kasaeian A, Khader Y, Khang YH, Kumar A, Kutz M, Larson H, Lopez A, Lunevicius R, Malekzadeh R, McAlinden C, Meier T, Mendoza W, Mokdad A, Moradi-Lakeh M, Nagel G, Nguyen Q, Nguyen G, Ogbo F, Patton G, Pereira DM, Pourmalek F, Qorbani M, Radfar A, Roshandel G, Salomon JA, Sanabria J, Sartorius B, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Sepanlou S, Shackelford K, Shore H, Sun J, Mengistu DT, Topór-Mądry R, Tran B, Ukwaja KN, Vlassov V, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wakayo T, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Yonemoto N, Younis M, Yu C, Zaidi Z, Zhu L, Murray CJL, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies From 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and National Level: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1683-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1459] [Cited by in RCA: 1495] [Article Influence: 186.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fang F, Wang X, Song T. Five-CpG-based prognostic signature for predicting survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer Biol Med. 2018;15:425-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Guo P, He Y, Chen L, Qi L, Liu D, Chen Z, Xiao M, Chen L, Luo Y, Zhang N, Guo H. Cytosolic phospholipase A2α modulates cell-matrix adhesion via the FAK/paxillin pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Med. 2019;16:377-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Huang X, Liu F, Zhu C, Cai J, Wang H, Wang X, He S, Liu C, Yao L, Ding Z, Zhang Y, Zhang T. Suppression of KIF3B expression inhibits human hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:795-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Myers SM, Collins I. Recent findings and future directions for interpolar mitotic kinesin inhibitors in cancer therapy. Future Med Chem. 2016;8:463-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nagahara M, Nishida N, Iwatsuki M, Ishimaru S, Mimori K, Tanaka F, Nakagawa T, Sato T, Sugihara K, Hoon DS, Mori M. Kinesin 18A expression: clinical relevance to colorectal cancer progression. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2543-2552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu X, Gong H, Huang K. Oncogenic role of kinesin proteins and targeting kinesin therapy. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:651-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Marszalek JR, Weiner JA, Farlow SJ, Chun J, Goldstein LS. Novel dendritic kinesin sorting identified by different process targeting of two related kinesins: KIF21A and KIF21B. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:469-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Moores CA, Milligan RA. Lucky 13-microtubule depolymerisation by kinesin-13 motors. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3905-3913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Walczak CE, Gayek S, Ohi R. Microtubule-depolymerizing kinesins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2013;29:417-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Anderson CA, Massey DC, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ, Tremelling M, Fisher SA, Gwilliam R, Jacob J, Nimmo ER, Drummond H, Lees CW, Onnie CM, Hanson C, Blaszczyk K, Ravindrarajah R, Hunt S, Varma D, Hammond N, Lewis G, Attlesey H, Watkins N, Ouwehand W, Strachan D, McArdle W, Lewis CM; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, Lobo A, Sanderson J, Jewell DP, Deloukas P, Mansfield JC, Mathew CG, Satsangi J, Parkes M. Investigation of Crohn's disease risk loci in ulcerative colitis further defines their molecular relationship. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:523-9.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Swarnkar S, Avchalumov Y, Raveendra BL, Grinman E, Puthanveettil SV. Kinesin Family of Proteins Kif11 and Kif21B Act as Inhibitory Constraints of Excitatory Synaptic Transmission Through Distinct Mechanisms. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rath O, Kozielski F. Kinesins and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:527-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Miki H, Okada Y, Hirokawa N. Analysis of the kinesin superfamily: insights into structure and function. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:467-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 541] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chandrasekaran G, Tátrai P, Gergely F. Hitting the brakes: targeting microtubule motors in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:693-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vale RD, Reese TS, Sheetz MP. Identification of a novel force-generating protein, kinesin, involved in microtubule-based motility. Cell. 1985;42:39-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1454] [Cited by in RCA: 1410] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dugas JC, Tai YC, Speed TP, Ngai J, Barres BA. Functional genomic analysis of oligodendrocyte differentiation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10967-10983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Labonté D, Thies E, Pechmann Y, Groffen AJ, Verhage M, Smit AB, van Kesteren RE, Kneussel M. TRIM3 regulates the motility of the kinesin motor protein KIF21B. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Muhia M, Thies E, Labonté D, Ghiretti AE, Gromova KV, Xompero F, Lappe-Siefke C, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Kuhl D, Schweizer M, Ohana O, Schwarz JR, Holzbaur ELF, Kneussel M. The Kinesin KIF21B Regulates Microtubule Dynamics and Is Essential for Neuronal Morphology, Synapse Function, and Learning and Memory. Cell Rep. 2016;15:968-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | van Riel WE, Rai A, Bianchi S, Katrukha EA, Liu Q, Heck AJ, Hoogenraad CC, Steinmetz MO, Kapitein LC, Akhmanova A. Kinesin-4 KIF21B is a potent microtubule pausing factor. Elife. 2017;6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ghiretti AE, Thies E, Tokito MK, Lin T, Ostap EM, Kneussel M, Holzbaur ELF. Activity-Dependent Regulation of Distinct Transport and Cytoskeletal Remodeling Functions of the Dendritic Kinesin KIF21B. Neuron. 2016;92:857-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | He M, Subramanian R, Bangs F, Omelchenko T, Liem KF, Kapoor TM, Anderson KV. The kinesin-4 protein Kif7 regulates mammalian Hedgehog signalling by organizing the cilium tip compartment. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:663-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |