Published online Jan 15, 2020. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i1.101

Peer-review started: August 30, 2019

First decision: October 14, 2019

Revised: October 25, 2019

Accepted: October 31, 2019

Article in press: October 31, 2019

Published online: January 15, 2020

Processing time: 123 Days and 2.3 Hours

Primary gastric adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) is an exceedingly rare histological subtype. Gastric signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC) is a unique subtype with distinct tumor biology and clinical features. The prognosis of gastric ASC vs SRC has not been well established to date. We hypothesized that further knowledge about these distinct cancers would improve the clinical management of such patients.

To investigate the clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of gastric ASC vs SRC.

A cohort of gastric cancer patients was retrospectively collected from the Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program database. The 1:4 propensity score matching was performed among this cohort. The clinicopathological features and prognosis of gastric ASC were compared with gastric SRC by descriptive statistics. Kaplan-Meier method was utilized to calculate the median survival of the two groups of patients. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to identify prognostic factors.

Totally 6063 patients with gastric ASC or SRC were identified. A cohort of 465 patients was recruited to the matched population, including 370 patients with SRC and 95 patients with ASC. Gastric ASC showed an inferior prognosis to SRC after propensity score matching. In the post-matching cohort, the median cancer specific survival was 13.0 (9.7-16.3) mo in the ASC group vs 20.0 (15.7-24.3) mo in the SRC group, and the median overall survival had a similar trend (P < 0.05). ASC and higher tumor-node-metastasis stage were independently associated with a poor survival, while radiotherapy and surgery were independent protective factors for improved prognosis. Subgroup survival analysis revealed that the prognosis of ASC was inferior to SRC only in stages I and II patients.

ASC may have an inferior prognosis to SRC in patients with stages I and II gastric cancer. Our study supports radiotherapy and surgery for the future management of this clinically rare entity.

Core tip: The prognosis of gastric adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) vs signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC) has not been well established to date. Our study used both propensity score matching method and multivariate Cox regression analysis to adjust the potential bias caused by the imbalanced distribution of confounding factors. We found that ASC may have an inferior prognosis to SRC in patients with stages I and II gastric cancer. Radiotherapy and surgery were proved to be independent protective factors for improving their prognosis.

- Citation: Chu YX, Gong HY, Hu QY, Song QB. Adenosquamous carcinoma may have an inferior prognosis to signet ring cell carcinoma in patients with stages I and II gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2020; 12(1): 101-112

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v12/i1/101.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v12.i1.101

Gastric cancer (GC) is still the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide[1]. It is also the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and was responsible for over 1000000 new cases in 2018 and an estimated 783000 deaths globally[2]. GC has increasingly been recognized as a heterogeneous disease, each histologic subtype of GC differs in its biology, especially in its metabolic profiles[3], so histology is very important in individualized evaluation of patients with GC. Among the various histologic types of GC, signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC) is a unique subtype with distinct tumor biology and clinical features, so it should be analyzed separately[4]. By contrast, adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) in GC is relatively rare. ASC accounts for only 0.2%-0.4% of all gastric carcinomas[5]. According to the World Health Organization international histological classification of tumors, SRC is defined as a tumor with only intracellular mucin pools[6]. Comparatively, the diagnosis of ASC requires coexistence of both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in the primary tumor, and squamous component should exceed 25% of the primary tumor[7].

Previous studies revealed that primary gastric ASC exhibited early tumor progression and a worse prognosis than some typical gastric carcinomas[8]. There have been two major proposed mechanisms to explain the poor prognosis of ASC in GC. First, this rare subtype may have more extensive tumor depth and higher frequencies of lymphatic and vascular permeations of the carcinoma cells[9]. Second, adenocarcinoma predominate histology may be associated with a higher risk of metastatic disease compared to squamous carcinoma predominate histology[10]. Due to the rare incidence, most of the literature about gastric ASC is described in case reports. The study on gastric ASC with large series is still lacking. The prognosis of ASC vs SRC has not been well established to date. Actually, a variety of issues about gastric ASC are still unresolved.

In this study, we utilized the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to extract a large cohort of patients to investigate the survival differences between ASC and SRC. Cancer-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS) were comprehensively compared between the two groups of patients. We sought to clarify the clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of gastric ASC vs SRC based on a large population analysis. Our study may intensify the current knowledge about these tumors and provide additional guidance for their management.

All the data in this study were extracted from SEER 18 registries Custom Data (with additional treatment fields). The SEER database comprises 18 cancer registries and covers approximately 30% of the United States population. The patients were selected using SEER Stat version 8.3.5 software directly. The patient information in SEER database is completely de-identified and publicly available, so this study was exempt from ethical approval from human study subcommittee. We initiated the following inclusion criteria to select eligible patients: (1) All patients were diagnosed from 2004 to 2015; (2) Primary site was the stomach; (3) Behavior recode for analysis was malignant; (4) Primary gastric cancer was the first or only cancer diagnosis; (5) Histological types were confined only to SRC (ICD-03, 8490/3) and ASC (ICD-03, 8560/3); and (6) The follow-up data were complete. The diagnosis was not gained from any death certificate or autopsy. Those patients with unknown information about table variables were excluded.

The following variables were extracted for each patient: Age at diagnosis, gender, race, marital status, tumor size, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, tumor depth, LN metastasis, distant metastasis, radiation, surgery, histological type, survival months, CSS, and OS. CSS was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to the date of death caused by gastric cancer. OS was defined as the duration from diagnosis to death from any cause. In our study, CSS was the primary endpoint, and OS was the secondary endpoint.

The patients were divided into patients with gastric SRC vs those with ASC. Given that the two cohorts dichotomized above were not randomized, unbalanced variables might engender selection bias, so we utilized a 1:4 propensity-score matching (PSM) method to control the non-random assignment of patients. A logistic regression model that predicts the likelihood of being assigned to ASC was constructed and set as the propensity score. The propensity scores were calculated according to unbalanced covariates. The PSM adopted nearest-neighbor matching algorithm. The caliper width was 0.01. No replacement was allowed, and all patients were matched only once. The baseline characteristics were compared in both matched and unmatched cohorts by chi-square tests. The survival curves of each histologic group were compared by Kaplan-Meier plots with log-rank test. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to identify prognostic factors in the post-matching cohort. Variables with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis were further adjusted through multivariate analysis. PSM was conducted with R version 3.5.3. Statistical analyses were completed with SPSS statistical software, version 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Preliminarily, 10646 patients with gastric ASC or SRC were collected, but 4583 cases were excluded because of any missing data or unknown of table variables. Finally, a total of 6063 eligible patients were included in this study. Among the unmatched cohort, 5968 (98.4%) patients had SRC and 95 (1.6%) patients had ASC. The distributions of age, gender, race, marital status, LN metastasis, and radiation were significantly different between the two groups (P < 0.05). Compared with those SRC patients, the ASC patients were more likely to have age > 60 years old (66.3% vs 52.7%), be male (74.7% vs 52.7%) while less female (25.3% vs 47.3%), had a relatively higher proportion of white population (77.9% vs 69.5%), and be married (77.9% vs 61.7%). As for LN metastasis, the ASC patients showed more N1 (48.4% vs 34.9%) and N2 (16.8% vs 15.5%). With respect to radiation, more ASC patients received radiotherapy (35.8% vs 23.7%). No differences were observed in terms of tumor size, TNM stage, tumor depth, distant metastasis, or surgery (P > 0.05). The patients’ characteristics before PSM are summarized in Table 1.

| Characteristic | SRC | ASC | Total | P value |

| n = 5968 (98.4) | n = 95 (1.6) | n = 6063 (100) | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.008 | |||

| ≤ 60 | 2823 (47.3) | 32 (33.7) | 2855 (47.1) | |

| > 60 | 3145 (52.7) | 63 (66.3) | 3208 (52.9) | |

| Gender | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 3146 (52.7) | 71 (74.7) | 3217 (53.1) | |

| Female | 2822 (47.3) | 24 (25.3) | 2846 (46.9) | |

| Race | 0.045 | |||

| White | 4147 (69.5) | 74 (77.9) | 4221 (69.6) | |

| Black | 725 (12.1) | 13 (13.7) | 738 (12.2) | |

| Others | 1096 (18.4) | 8 (8.4) | 1104 (18.2) | |

| Marital status | 0.001 | |||

| Not married | 2287 (38.3) | 21 (22.1) | 2308 (38.1) | |

| Married | 3681 (61.7) | 74 (77.9) | 3755 (61.9) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | 0.220 | |||

| ≤ 50 | 2271 (38.1) | 42 (44.2) | 2313 (38.1) | |

| > 50 | 3697 (61.9) | 53 (55.8) | 3750 (61.9) | |

| TNM Stage | 0.299 | |||

| I | 1595 (26.7) | 21 (22.1) | 1616 (26.7) | |

| II | 888 (14.9) | 20 (21.1) | 908 (15.0) | |

| III | 1129 (18.9) | 15 (15.8) | 1144 (18.9) | |

| IV | 2356 (39.5) | 39 (41.1) | 2395 (39.5) | |

| Tumor depth | 0.139 | |||

| T1 | 1398 (23.4) | 16 (16.8) | 1414 (23.3) | |

| T2 | 2177 (36.5) | 45 (47.4) | 2222 (36.6) | |

| T3 | 1384 (23.2) | 18 (18.9) | 1402 (23.1) | |

| T4 | 1009 (16.9) | 16 (16.8) | 1025 (16.9) | |

| LN metastasis | 0.011 | |||

| N0 | 2472 (41.4) | 31 (32.6) | 2503 (41.3) | |

| N1 | 2080 (34.9) | 46 (48.4) | 2126 (35.1) | |

| N2 | 926 (15.5) | 16 (16.8) | 942 (15.5) | |

| N3 | 490 (8.2) | 2 (2.1) | 492 (8.1) | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.966 | |||

| No | 4197 (70.3) | 67 (70.5) | 4264 (70.3) | |

| Yes | 1771 (29.7) | 28 (29.5) | 1799 (29.7) | |

| Radiotherapy | 0.006 | |||

| No | 4553 (76.3) | 61 (64.2) | 4614 (76.1) | |

| Yes | 1415 (23.7) | 34 (35.8) | 1449 (23.9) | |

| Surgery | 0.231 | |||

| No | 2047 (34.3) | 27 (28.4) | 2074 (34.2) | |

| Yes | 3921 (65.7) | 68 (71.6) | 3989 (65.8) |

A 1:4 PSM was initiated. The logit of propensity score for histological type was derived from other covariates. Totally 465 patients were matched, including 95 ASC patients and 370 SRC patients. After the PSM, all covariates were well balanced with no significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05). The patients’ characteristics categorized by histology after PSM are displayed in Table 2.

| Characteristic | SRC | ASC | Total | P value |

| n = 370 (79.6) | n = 95 (20.4) | n = 465 (100) | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.754 | |||

| ≤ 60 | 131 (35.4) | 32 (33.7) | 163 (35.1) | |

| > 60 | 239 (64.6) | 63 (66.3) | 302 (64.9) | |

| Gender | 0.809 | |||

| Male | 272 (73.5) | 71 (74.7) | 343 (73.8) | |

| Female | 98 (26.5) | 24 (25.3) | 122 (26.2) | |

| Race | 0.845 | |||

| White | 290 (78.4) | 74 (77.9) | 364 (78.3) | |

| Black | 44 (11.9) | 13 (13.7) | 57 (12.3) | |

| Others | 36 (9.7) | 8 (8.4) | 44 (9.5) | |

| Marital status | 0.901 | |||

| Not married | 84 (22.7) | 21 (22.1) | 105 (22.6) | |

| Married | 286 (77.3) | 74 (77.9) | 360 (77.4) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | 0.828 | |||

| ≤ 50 | 159 (43.0) | 42 (44.2) | 201 (43.2) | |

| > 50 | 211 (57.0) | 53 (55.8) | 264 (56.8) | |

| Stage | 0.365 | |||

| I | 94 (25.4) | 21 (22.1) | 115 (24.7) | |

| II | 55 (14.9) | 20 (21.1) | 75 (16.1) | |

| III | 77 (20.8) | 15 (15.8) | 92 (19.8) | |

| IV | 144 (38.9) | 39 (41.1) | 183 (39.4) | |

| Tumor depth | 0.598 | |||

| T1 | 77 (20.8) | 16 (16.8) | 93 (20.0) | |

| T2 | 156 (42.2) | 45 (47.4) | 201 (43.2) | |

| T3 | 84 (22.7) | 18 (18.9) | 102 (21.9) | |

| T4 | 53 (14.3) | 16 (16.8) | 69 (14.8) | |

| LN metastasis | 0.151 | |||

| N0 | 151 (40.8) | 31 (32.6) | 182 (39.1) | |

| N1 | 134 (36.2) | 46 (48.4) | 180 (38.7) | |

| N2 | 69 (18.6) | 16 (16.8) | 85 (18.3) | |

| N3 | 16 (4.3) | 2 (2.1) | 18 (3.9) | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.840 | |||

| No | 257 (69.5) | 67 (70.5) | 324 (69.7) | |

| Yes | 113 (30.5) | 28 (29.5) | 141 (30.3) | |

| Radiotherapy | 0.786 | |||

| No | 232 (62.7) | 61 (64.2) | 293 (63.0) | |

| Yes | 138 (37.3) | 34 (35.8) | 172 (37.0) | |

| Surgery | 0.883 | |||

| No | 108 (29.2) | 27 (28.4) | 135 (29.0) | |

| Yes | 262 (70.8) | 68 (71.6) | 330 (71.0) |

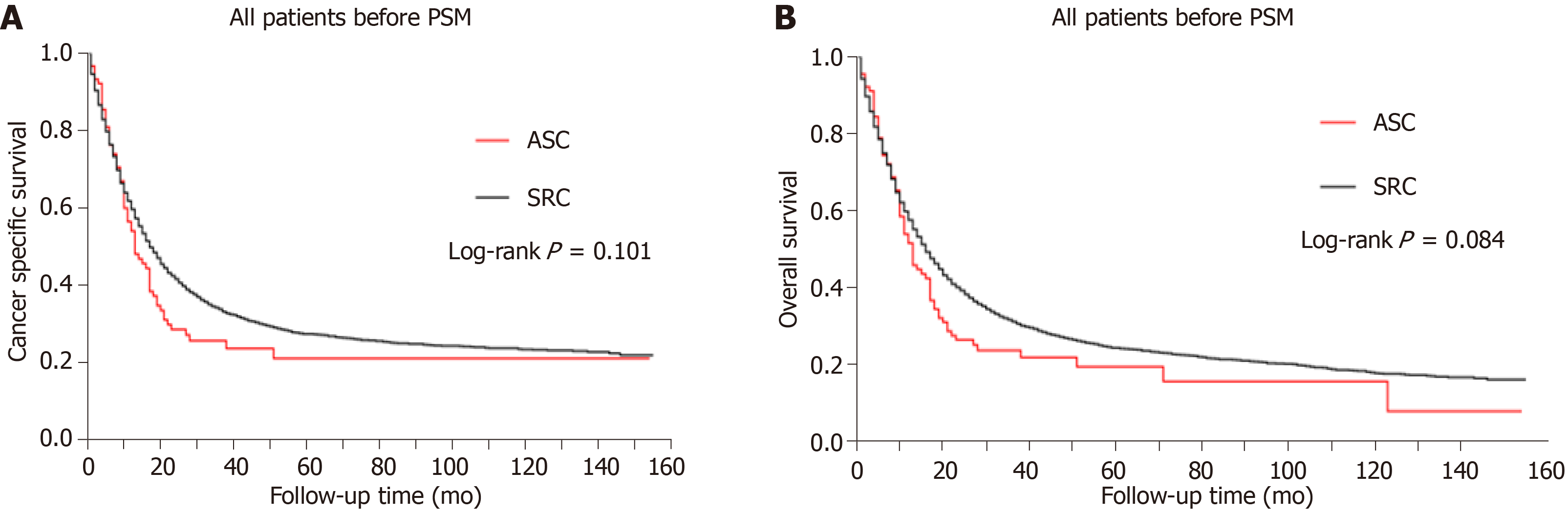

As for the 6063 patients finally enrolled, 4560 patients were dead at the end of the last follow-up. Moreover, 4160 patients were dead from gastric cancer specifically. The prognosis of gastric SRC vs ASC before PSM was compared. The Kaplan-Meier plots showed that the prognosis of SRC was comparable to that of ASC in both CSS and OS curves (Figure 1, P > 0.05). The median CSS of the SRC group was 16.0 (15.2-16.8) mo, while that of the ASC group was 13.0 (9.7-16.3) mo (P = 0.101; Table 3). Similarly, the median OS of the SRC group was not significantly different from that of the ASC group (P = 0.084; Table 3). Hence, the results indicated the prognosis was not statistically different between gastric SRC and ASC before PSM.

| Patients, n | Median CSS 95%CI, mo | Median OS 95%CI, mo | |

| Before PSM | |||

| SRC | 5968 | 16.0 (15.2-16.8) | 15.0 (14.3-15.7) |

| ASC | 95 | 13.0 (9.7-16.3) | 12.0 (9.5-14.5) |

| P value | 0.101 | 0.084 | |

| After PSM | |||

| SRC | 370 | 20.0 (15.7-24.3) | 19.0 (14.9-23.1) |

| ASC | 95 | 13.0 (9.7-16.3) | 12.0 (9.5-14.5) |

| P value | 0.027 | 0.017 |

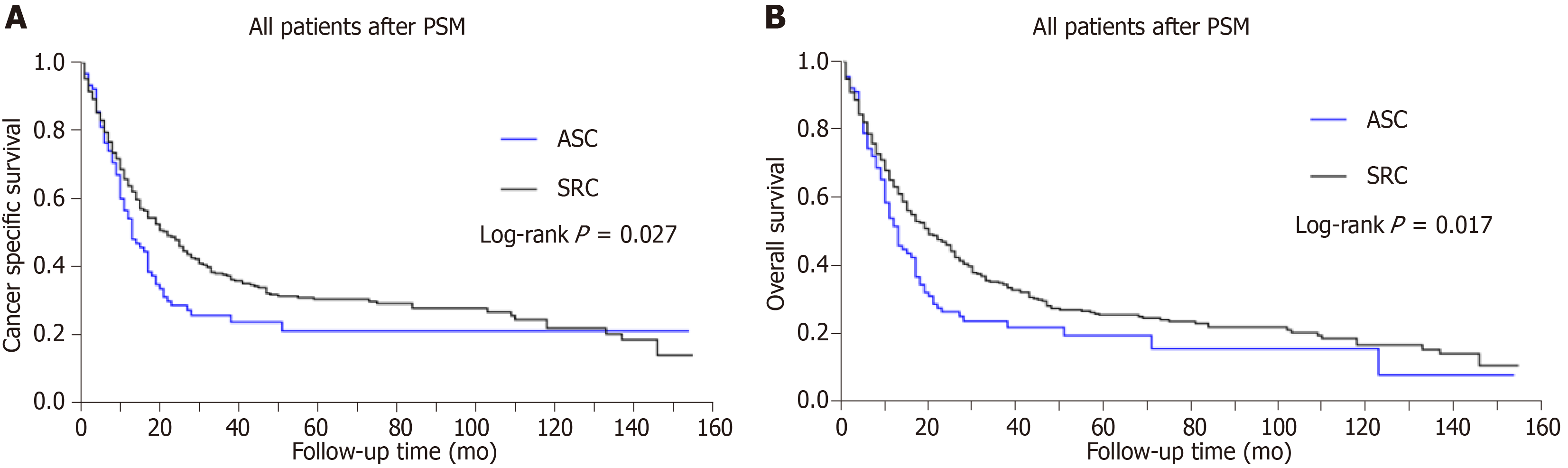

We initiated a 1:4 (ASC:SRC) matched case-control analysis by PSM, in order to adjust the baseline characteristic differences between the two groups. The PSM analysis resulted in a balanced cohort including the ASC group (n = 95) and the SRC group (n = 370). As for the cohort after PSM, statistically significant differences appeared in both CSS and OS, dejecting the ASC group compared with the SRC group (P < 0.05 for both endpoints; Figure 2). Furthermore, the median CSS was 13.0 (9.7-16.3) mo in ASC vs 20.0 (15.7-24.3) mo in SRC group (P = 0.027; Table 3). In parallel, the median OS of the ASC group was also inferior to that of the SRC group (Table 3, P = 0.017). The survival curves of CSS and OS after PSM are exhibited in Figure 2. Obviously, the ASC patients had an inferior prognosis to SRC patients in matched groups.

The Cox proportional hazard models were constructed to evaluate the impact of clinicopathological factors on CSS of the post-matching cohort (Table 4). In univariate analysis, the variables significantly associated with CSS were histological type, marital status, tumor size, TNM stage, tumor depth, distant metastasis, radiation, and surgery (P < 0.05). ASC was found to be a risk factor for poor prognosis [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.343, 95%CI = 1.029-1.752, P < 0.05]. All the significant variables mentioned above were subsequently included to the multivariate Cox regression analysis. Multivariable analysis confirmed some of the prognostic factors identified in univariate analysis. After adjusting for other confounding predictors, histological type and TNM stage were proved to be independent risk factors for poor survival (HR > 1, P < 0.05), while radiotherapy and surgery were independent protective factors for favorable prognosis (HR < 1, P < 0.05). Anyway, ASC was still associated with an inferior prognosis to SRC (HR = 1.316, 95%CI = 1.004-1.726, P < 0.05). The detailed results are available in Table 4.

| Characteristic | Univariate Cox | Multivariate Cox | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Histological type | ||||

| SRC | Reference | Reference | ||

| ASC | 1.343 (1.029-1.752) | 0.030 | 1.316 (1.004-1.726) | 0.047 |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| ≤ 60 | Reference | NI | ||

| > 60 | 1.027 (0.819-1.288) | 0.815 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Reference | NI | ||

| Female | 0.952 (0.740-1.223) | 0.698 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | NI | ||

| Black | 1.199 (0.870-1.652) | 0.268 | ||

| Others | 0.883 (0.597-1.304) | 0.531 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Not married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Married | 0.768 (0.593-0.994) | 0.045 | 0.709 (0.540-0.932) | 0.014 |

| Tumor size (mm) | ||||

| ≤ 50 | Reference | Reference | ||

| > 50 | 1.994 (1.587-2.503) | <0.001 | 1.217 (0.947-1.564) | 0.125 |

| Stage | ||||

| I | Reference | Reference | ||

| II | 1.482 (0.993-2.212) | 0.054 | 1.564 (1.021-2.394) | 0.040 |

| III | 2.472 (1.714-3.564) | < 0.001 | 2.460 (1.601-3.780) | < 0.001 |

| IV | 5.179 (3.739-7.175) | < 0.001 | 2.884 (1.665-4.997) | < 0.001 |

| Tumor depth | ||||

| T1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| T2 | 0.962(0.705-1.312) | 0.805 | 1.296 (0.923-1.821) | 0.135 |

| T3 | 1.478(1.051-2.077) | 0.025 | 1.482 (0.986-2.228) | 0.058 |

| T4 | 1.801 (1.243-2.609) | 0.002 | 1.070 (0.699-1.638) | 0.757 |

| LN metastasis | ||||

| N0 | Reference | NI | ||

| N1 | 0.978(0.760-1.258) | 0.863 | ||

| N2 | 1.218 (0.901-1.647) | 0.200 | ||

| N3 | 1.642 (0.985-2.737) | 0.057 | ||

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 4.303 (3.397-5.451) | < 0.001 | 1.278 (0.778-2.100) | 0.333 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.484(0.383-0.612) | < 0.001 | 0.587 (0.444-0.776) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.244(0.192-0.311) | < 0.001 | 0.450 (0.319-0.635) | < 0.001 |

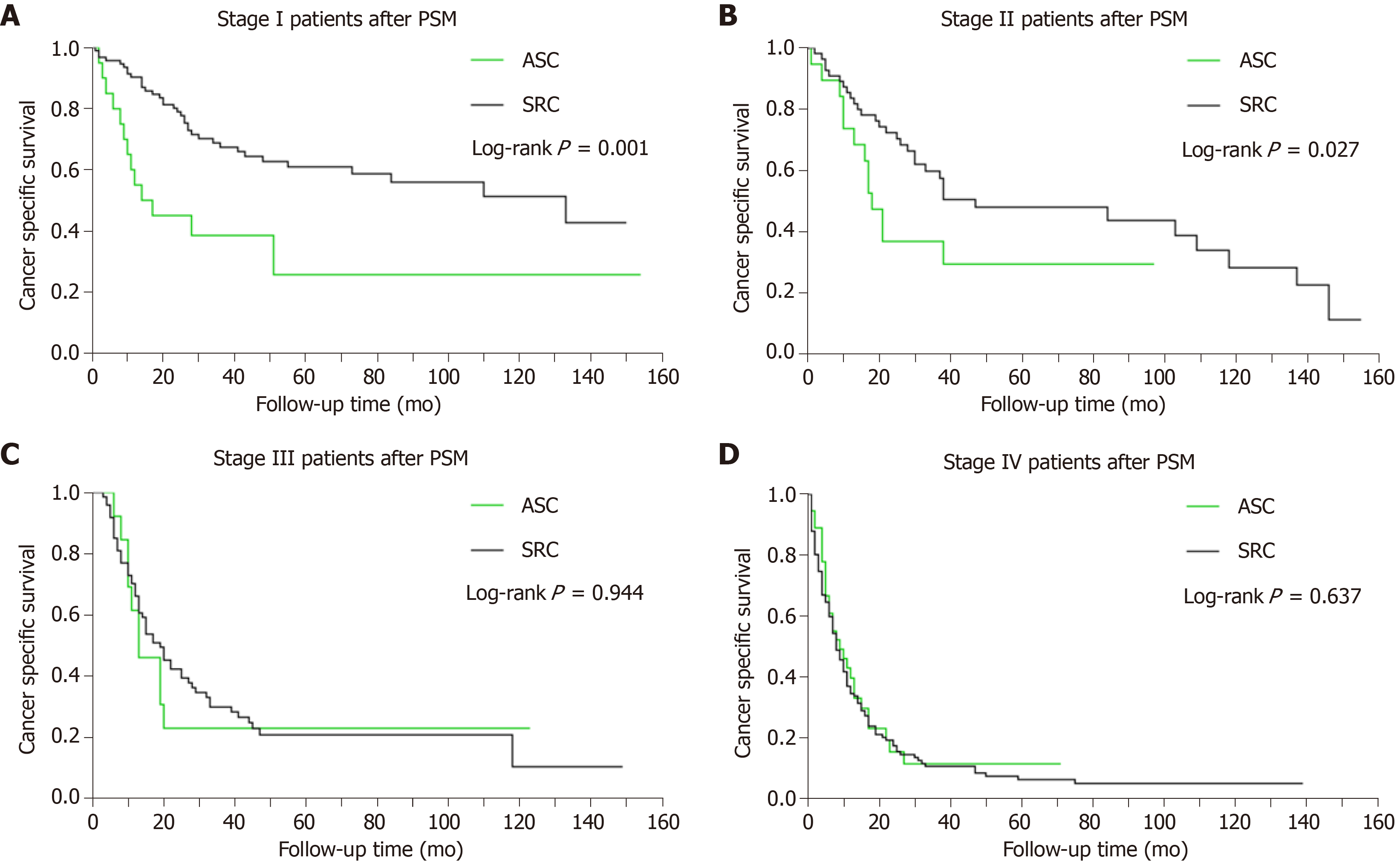

Given that TNM stage is also independently associated with the patients’ survival after PSM, we performed a subgroup analysis to highlight the impact of histological type on the prognosis of patients. The Kaplan-Meier plots revealed that the CSS of gastric ASC was worse than that of gastric SRC in both stages I (P < 0.001) and II (P < 0.05) patients. However, no significant survival difference was found for ASC vs SRC in either stage III or IV (P > 0.05). Thus, the prognosis of ASC was inferior to SRC only in stages I and II patients. The survival curves of CSS stratified by TNM stage are illustrated in Figure 3.

Primary gastric ASC is an extremely rare subtype[11]. The clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of gastric ASC are still poorly understood. Based on a large cohort from the SEER database, we utilized PSM analysis to evaluate the prognosis of ASC vs SRC for patients with gastric cancer. Moreover, we also used Cox proportional hazard regression models to identify prognostic factors for the post-matching population. The overall results suggest that ASC had an inferior survival to SRC in patients with gastric cancer. ASC and higher TNM stages were independently associated with a poor prognosis.

The clinicopathological features and prognosis of gastric ASC have been reviewed by several previous studies. Based on the National Cancer Database analysis, a recent original research has reported the clinical features and outcomes of gastric squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and ASC. They collected 61215 patients with primary gastric cancer. ASC only accounted for 0.5%. The median OS was 9.9 mo in ASC vs 13.2 mo in adenocarcinoma. On multivariate analysis, ASC histology was still associated with a worse survival compared to adenocarcinoma[12]. Furthermore, another study reported the clinical features and outcomes of 167 gastric ASC cases. Only 109 cases with R0 resection were recruited in survival analysis. Their results revealed that the median OS time was 17 mo for patients with gastric ASC receiving R0 resection. They also found that the prognosis of gastric ASC was significantly poorer than that of gastric adenocarcinoma[13]. Quan et al[14] also reported that the median OS of gastric ASC was 12 mo, and 87.5% of the patients survived for less than 24 mo after diagnosis. In our present study, we compared the survival outcomes of gastric ASC with SRC. As for our matched cohort, the median OS was 12.0 (9.5-14.5) mo in ASC vs 19.0 (14.9-23.1) mo in SRC group. In parallel, the median CSS of ASC was also significantly worse than that of SRC. Consistently, the prognosis of ASC was inferior to that of SRC after PSM analysis.

When it comes to the prognostic factors for gastric ASC, we found that the histological type ASC and higher TNM stage were independent risk factors for poor survival (HR > 1, P < 0.05), while radiotherapy (HR = 0.587; 95%CI: 0.444-0.776, P < 0.001) and surgery were independent protective factors for favorable prognosis (HR < 1, P < 0.05). So far, surgery remains the optimal treatment for gastric cancer without distant metastasis[15]. So the survival advantage of gastrectomy has been further confirmed by our study. Additionally, radiotherapy has been reported to be an effective adjuvant treatment for improving the OS in patients with gastric cancer after resection[16]. Considering that squamous cell carcinoma is generally sensitive to radiation therapy, the squamous component of gastric ASC may specifically benefit from radiotherapy[17]. Therefore, our study has provided evidence to support radiotherapy for patients with gastric ASC.

In addition to histological type, other confounders such as tumor TNM stage may also account for the potentially important survival differences. In order to further adjust the confounding factors, we performed subgroup survival analysis by TNM stage. Our results revealed that the CSS of gastric ASC was significantly worse than that of SRC in stages I and II patients, whereas no significant survival difference was found for stages III and IV patients. A recent study revealed that half of gastric ASC cases were diagnosed at advanced stages, and most patients had lymph node metastasis[18]. These results suggest that gastric ASC has an aggressive clinical course compared with conventional gastric cancer. The prognosis of stages I and II ASC patients should be concerned.

In terms of the prognosis for patients with gastric SRC, a recent review has indicated that early SRC had a better clinical outcome, but advanced SRC was generally considered to have a worse prognosis. Therapeutic strategies are still controversial for these patients[19]. Consistently, our study also revealed that stages I and II SRC patients had better survival curves than ASC patients. Their median CSS was 20.0 (15.7-24.3) mo, and median OS was 19.0 (14.9-23.1) mo. Our Cox proportional hazard regression models identified radiotherapy and surgery as independent protective factors for improving their prognosis (HR < 1, P < 0.05). Hence, our results may improve the therapeutic recommendations for these patients.

There are several limitations in our study. First, the retrospective nature of the current study could not exclude the possibility of selection bias. Although we could balance known covariates by PSM analysis, there may be unmeasured confounders not addressed in propensity matching. Hence, the results of our study should be interpreted cautiously. Second, the constituent ratio of adenocarcinoma and SCC components varied among different primary tumors. The prognostic value of constituent ratio on the survival of gastric ASC could not be evaluated. Third, there were limited data about cancer recurrence and subsequent involved sites in SEER database, so the patterns of recurrence and corresponding impact on the prognosis of patients remain unclear. In spite of the limitations stated above, SEER registry data usually have high completeness and are representative of the real-world patient population. Thus, the results of our study are still considerably convincing.

The major strength of our study is that we used both PSM method and multivariate Cox regression analysis to adjust the potential bias caused by the imbalanced distribution of confounding factors. This doubly robust estimation combines two approaches to evaluate the causal effect of exposures on outcomes, which will encourage researchers to more fully interpret their findings on both scales[20].

In summary, gastric ASC differs significantly from gastric SRC in terms of clinicopathological characteristics. ASC may have an inferior prognosis to SRC in patients with stages I and II gastric cancer, so greater attention should be paid to these patients. Histological type ASC and higher TNM stage are associated a poor survival, but radiotherapy and surgery are independent protective factors for improving their prognosis. Our study supports radiotherapy and surgery for the future management of this clinically rare entity.

Adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) is a rare entity in gastric cancer, which exhibits early tumor progression and a poorer prognosis than other typical gastric adenocarcinoma. Gastric signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC) is a unique subtype with distinct tumor biology and clinical features. We hypothesized that further knowledge about these distinct cancers would improve the clinical management of such patients.

Given the relative rarity of these two subtypes in gastric cancer, the study on gastric ASC with large series is still lacking. The clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of ASC vs SRC has not been well established to date. The current study adopted a large cohort of such patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Study on the clinicopathological features, treatment, and prognosis of such patients may bring deeper knowledge on these tumors and provide additional assistance for their treatment.

The goal of our study was to evaluate the clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of ASC vs SRC based on a large cohort from the SEER database. Achieving this objective may provide additional assistance for their management.

We conducted a retrospective study using a large cohort from the SEER database. The clinicopathological features of patients with ASC vs SRC were comprehensively compared by chi-square tests. We used both propensity-score matching (PSM) method and multivariate Cox regression analysis to adjust the potential bias caused by the imbalanced distribution of confounding factors. Clinical outcomes including cancer-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS) were also compared by the Kaplan-Meier method. The prognostic factors were identified.

A total of 6063 eligible patients were collected. After PSM, 370 patients with SRC and 95 patients with ASC were analyzed. In the post-matching cohort, gastric ASC showed an inferior prognosis to SRC in both CSS and OS. ASC and higher TNM stage were independently associated with a poor survival (HR > 1, P < 0.05), while radiotherapy (HR = 0.587; 95%CI: 0.444-0.776, P < 0.001) and surgery were independent protective factors for favorable prognosis (HR < 1, P < 0.05). Subgroup survival analysis revealed that the inferior prognosis was most significant in stages I and II patients.

ASC may have an inferior prognosis to SRC in patients with stages I and II gastric cancer, so greater attention should be paid to these patients. Our study supports radiotherapy and surgery for the future management of this clinically rare entity. Improved clinical and biological understanding of ASC vs SRC may lead to more individualized therapy for such patients.

Our study shows that gastric ASC has an inferior prognosis to SRC in stages I and II patients. Precautions should be taken to such patients. Radiotherapy and surgery have the potential to improve their clinical outcomes. Future long-term prospective studies are warranted to validate our findings.

Manuscript Source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Imaeda H, Koch TR S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Li Q, Zou J, Jia M, Li P, Zhang R, Han J, Huang K, Qiao Y, Xu T, Peng R, Song Q, Fu Z. Palliative Gastrectomy and Survival in Patients With Metastatic Gastric Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis of a Large Population-Based Study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Di Sibio A, Romano L, Giuliani A, Varrassi M, De Donato MC, Iacopino A, Perri M, Schietroma M, Carlei F, Di Cesare E, Masciocchi C. Nerve root metastasis of gastric adenocarcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;61:9-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yuan LW, Yamashita H, Seto Y. Glucose metabolism in gastric cancer: The cutting-edge. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2046-2059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chon HJ, Kim C, Cho A, Kim YM, Jang SJ, Kim BO, Park CH, Hyung WJ, Ahn JB, Noh SH, Yun M, Rha SY. The clinical implications of FDG-PET/CT differ according to histology in advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:113-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ebi M, Shimura T, Yamada S, Hirata Y, Tsukamoto H, Okamoto Y, Mizoshita T, Tanida S, Kataoka H, Kamiya T, Inagaki H, Joh T. A patient with gastric adenosquamous carcinoma with intraperitoneal free cancer cells who remained recurrence-free with postoperative S-1 chemotherapy. Intern Med. 2012;51:3125-3129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington MK, Carneiro F, Cree IA. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2019;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2428] [Article Influence: 485.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 7. | Shirahige A, Suzuki H, Oda I, Sekiguchi M, Mori G, Abe S, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Sekine S, Kushima R, Saito Y, Fukagawa T, Katai H. Fatal submucosal invasive gastric adenosquamous carcinoma detected at surveillance after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4385-4390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Faria GR, Eloy C, Preto JR, Costa EL, Almeida T, Barbosa J, Paiva ME, Sousa-Rodrigues J, Pimenta A. Primary gastric adenosquamous carcinoma in a Caucasian woman: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mori M, Iwashita A, Enjoji M. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the stomach. A clinicopathologic analysis of 28 cases. Cancer. 1986;57:333-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen YY, Li AF, Huang KH, Lan YT, Chen MH, Chao Y, Lo SS, Wu CW, Shyr YM, Fang WL. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the stomach and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2015;21:547-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bae HI, Seo AN. Early Gastric Adenosquamous Carcinoma Resected Using Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2019;13:165-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Akce M, Jiang R, Alese OB, Shaib WL, Wu C, Behera M, El-Rayes BF. Gastric squamous cell carcinoma and gastric adenosquamous carcinoma, clinical features and outcomes of rare clinical entities: a National Cancer Database (NCDB) analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:85-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Feng F, Zheng G, Qi J, Xu G, Wang F, Wang Q, Guo M, Lian X, Zhang H. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of gastric adenosquamous carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Quan J, Zhang R, Liang H, Li F, Liu H. The clinicopathologic and prognostic analysis of adenosquamous and squamous cell carcinoma of the stomach. Am Surg. 2013;79:E206-E208. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Alsina M, Miquel JM, Diez M, Castro S, Tabernero J. How I treat gastric adenocarcinoma. ESMO Open. 2019;4:e000521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stumpf PK, Amini A, Jones BL, Koshy M, Sher DJ, Lieu CH, Schefter TE, Goodman KA, Rusthoven CG. Adjuvant radiotherapy improves overall survival in patients with resected gastric adenocarcinoma: A National Cancer Data Base analysis. Cancer. 2017;123:3402-3409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Moro K, Nagahashi M, Naito T, Nagai Y, Katada T, Minagawa M, Hasegawa J, Tani T, Shimakage N, Usuda H, Gabriel E, Kawaguchi T, Takabe K, Wakai T. Gastric adenosquamous carcinoma producing granulocyte-colony stimulating factor: a case of a rare malignancy. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Miyake H, Miyasaka C, Ishida M, Miki H, Inoue K, Tsuta K. Simultaneous gastric adenosquamous carcinoma and gastric carcinoma with lymphoid stroma: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2019;11:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pernot S, Voron T, Perkins G, Lagorce-Pages C, Berger A, Taieb J. Signet-ring cell carcinoma of the stomach: Impact on prognosis and specific therapeutic challenge. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11428-11438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 20. | Antonelli J, Cefalu M, Palmer N, Agniel D. Doubly robust matching estimators for high dimensional confounding adjustment. Biometrics. 2018;74:1171-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |