Published online Feb 15, 2019. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i2.172

Peer-review started: November 15, 2018

First decision: December 24, 2018

Revised: December 31, 2018

Accepted: January 28, 2019

Article in press: January 28, 2019

Published online: February 15, 2019

Processing time: 93 Days and 8.3 Hours

Anal cancers are caused by human papilloma virus (HPV). Buschke-Lowenstein tumor also known as giant anal condyloma (GCA) is a variant of giant neglected anal tumors arising from warts caused by HPV infection. HPV are a family of double-stranded DNA viruses and primarily cause sexually transmitted disease of the genitalia and oropharyngeal mucosa. These tumors are slow growing; locally destructive large verrucous masses.

We present a series of two cases with large anal tumors harboring invasive cancers and highlight their presentation and management. Tumors with high risk HPV subtypes (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33) may progress into invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Untreated GCA can attain enormous size and extend into the pelvic organs and bony structures. Some tumors show malignant degeneration into SCC and are often difficult to diagnose given the large size of the tumors. Complete surgical excision with negative margins is the treatment of choice and necessary to prevent recurrence. This is often not feasible and leaves large surgical wounds with tissue defects with delay in healing and increases post-operative morbidity. Pelvic reconstructive techniques including muscle flaps and grafts are often necessary to close the defects. Human immunodeficiency virus and immunocompromised patients generally do poorly with standard treatments.

A multidisciplinary team of colorectal and plastic surgeons, medical and radiation oncologists along with combination treatment modalities are necessary when malignant transformation occurs in GCA, for optimal outcomes.

Core tip: Large anal condylomas are generally caused by low risk human papilloma virus 6, 11, however in certain instances can be caused by high risk subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33. Malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma may occur in large neglected tumors and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients. Deep core biopsy, P16 staining and positron emission tomography computed tomography scans are necessary to diagnose carcinoma and metastases. Due to enormous size of the tumors a multidisciplinary team approach is necessary with combination of neoadjuvant chemo radiation followed by wide excision of these tumors. Large perineal and pelvic defects may need pelvic reconstructive surgery. Patients with HIV and anal cancers carry a poor prognosis.

- Citation: Shenoy S, Nittala M, Assaf Y. Anal carcinoma in giant anal condyloma, multidisciplinary approach necessary for optimal outcome: Two case reports and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2019; 11(2): 172-180

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v11/i2/172.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v11.i2.172

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the anus is an uncommon malignancy; however, it continues to show a steady increasing trend in the United States. An estimated 8560 new cases will be diagnosed (0.5% of all cancers) in United States in the year 2018 with an estimated 1160 deaths. The overall 5-year survival rate for anal cancer continues to be marginal at 67% (range of 81% for localized disease and 29% for distant disease)[1]. The majority of these tumors are caused by high risk human papilloma virus (HPV) (subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33). HPV is the most common sexually transmitted disease (STD) in the United States. An estimated 1 in 5 adults in the United States are infected with HPV[2]. HPV is a family of double-stranded DNA viruses and cause carcinoma of the genitalia and oropharyngeal mucosa[3,4].

Buschke Lowenstein tumor also known as giant anal condyloma (GCA) is a variant of anal tumors caused by HPV infection. These tumors are slow growing; locally destructive verrucous tumor that was first described by Buschke and Lowenstein on the penis, but may occur elsewhere in the anogenital region[5]. The risk factors for anal cancer caused by HPV include receptive anal intercourse, multiple sexual partners, men who have sex with men (MSM), smokers and associations with other immunosuppressive STD such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients[6]. Untreated GCA can attain large size and extend into the pelvic organs and bony structures. Some tumors show malignant degeneration and are often difficult to diagnose given the large size of the tumors. Complete surgical excision with negative margins is the treatment of choice and necessary to prevent recurrence. This often leaves large surgical wounds with delay in healing and increases post-operative morbidity. A multidisciplinary treatment is necessary for optimal outcomes. We present our clinical experience of two cases of anal carcinoma associated with giant condyloma.

Chief complaints: We treated a 70-year-old heterosexual, HIV negative male patient with a giant peri-anal cancer.

History of present illness: He presented with a neglected slow growing anal wart for many years with intermittent bleeding and pruritus.

History of past illness: There was no significant past medical history or family history of malignancies.

Physical examination upon admission: Examination showed foul smelling giant anal tumor with areas of ulceration and necrosis. The tumor extended into the left scrotal skin, left thigh crease and to the lower left inguinal area (Figure 1).

Laboratory examinations: The serum chemistries and complete blood count was normal.

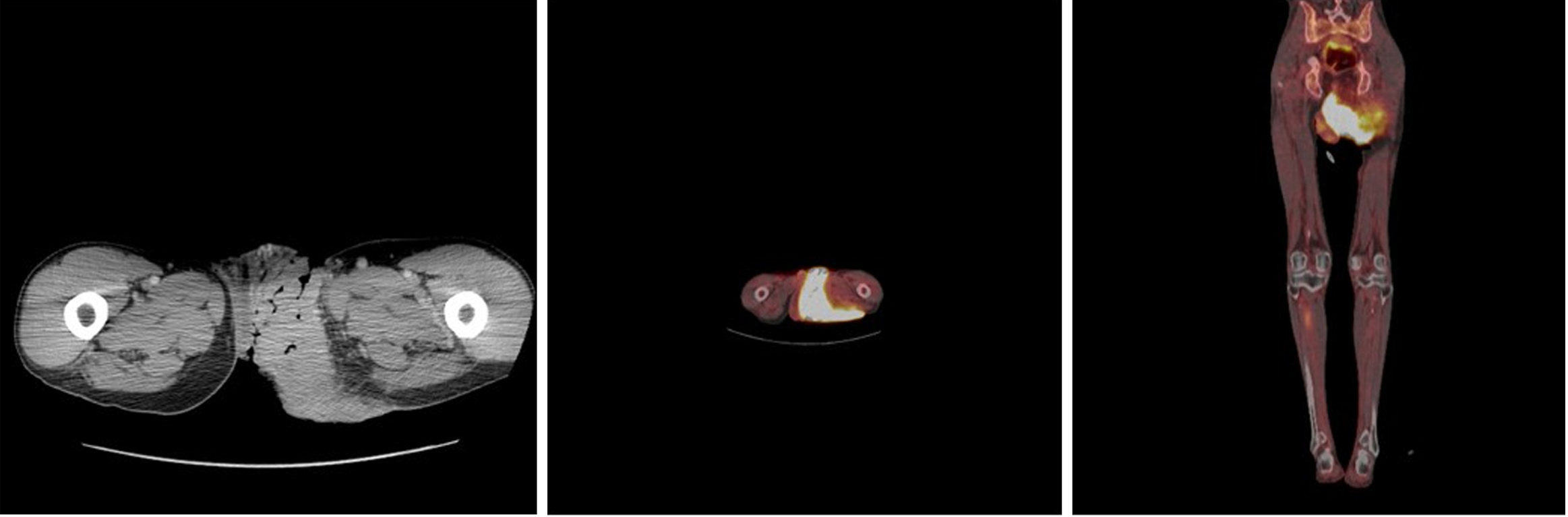

Imaging examinations: Colonoscopy was normal. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) of the ano-rectum showed no anal sphincter involvement. A deep core biopsy of the lesion confirmed SCC with p16 positivity suggestive of high risk HPV subtype. Whole body tumor positron emission tomography computed tomography (PET CT) scan confirmed a large hypermetabolic mass with an SUV max of 8.1 to 10.1 (Figure 2) without regional lymphadenopathy.

Chief complaints: A 58-year-old male, HIV positive on HAART (antiretroviral therapy) and a normal CD4 count > 1000 cells/uL and an undetectable HIV viral load presented with a large anal tumor.

History of present illness: He too presented with a neglected slow growing anal wart.

History of past illness: There was no family history of malignancies.

Physical examination upon admission: Examination confirmed a large anal mass with ulceration and necrosis. His tumor did involve the anal sphincters and the patient presented with anal incontinence.

Laboratory examinations: The serum chemistries and complete blood count was normal.

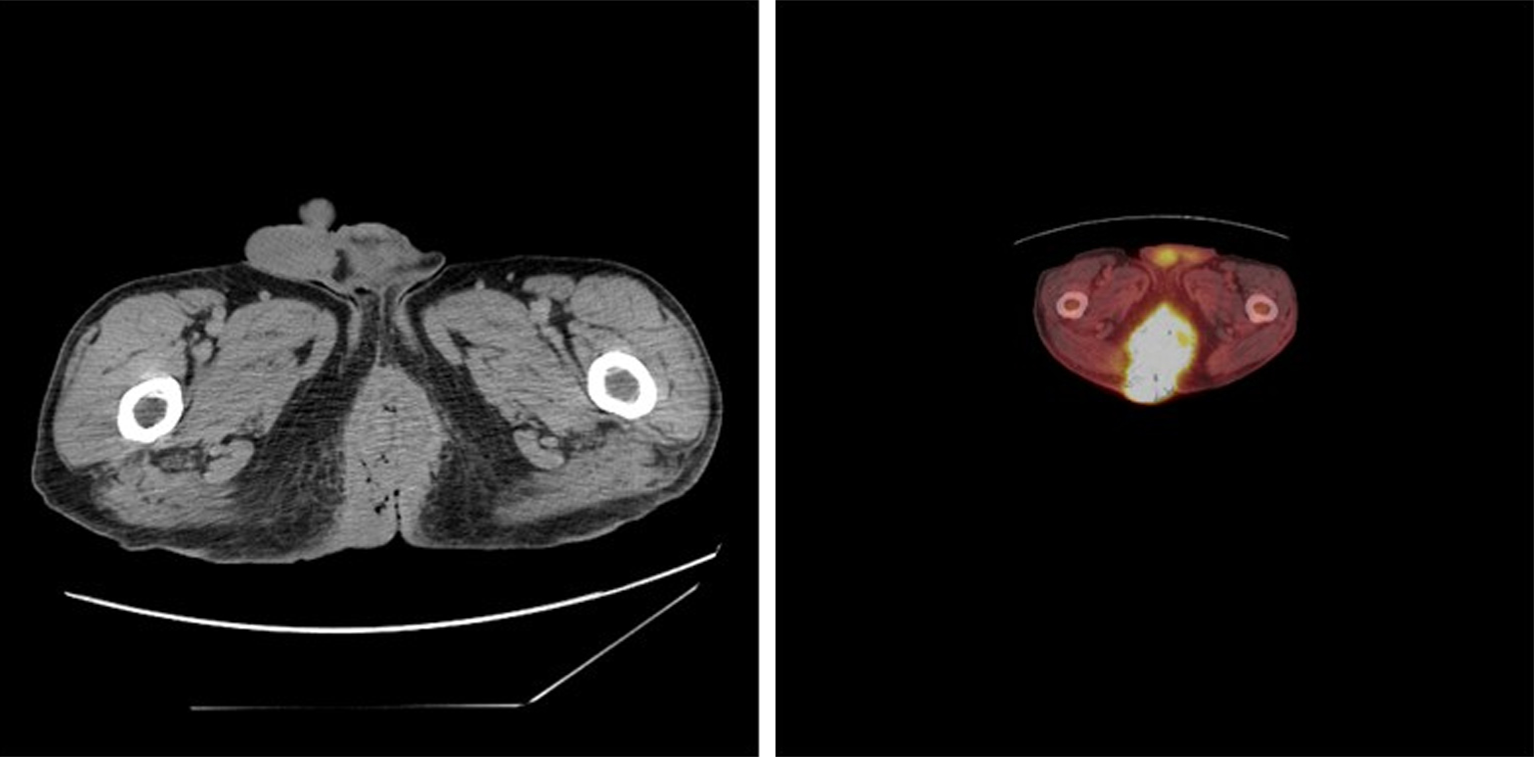

Imaging examinations: The colonoscopy exam confirmed a circumferential anal mass. EUS revealed involvement of the anal sphincters. Whole body PET CT scan confirmed the hypermetabolic anal and perianal mass with a SUV max of 8.1 (Figure 3). A deep core biopsy was performed and confirmed SCC with p16 positivity suggestive of high risk HPV subtype.

SCC of the anus, GCA, HPV positive.

SCC of the anus, GCA, HPV positive, HIV positive.

The case was discussed in institutional tumor board with surgeons, medical and radiation oncologists. Neoadjuvant chemo radiation (Nigro protocol) was administered to downsize of the tumor (Figure 4). This regimen consisted of preoperative chemotherapy, 5-fluorouracil (1000 mg/m2 per day) by continuous infusion on day 1-4 along with mitomycin C 10 mg/m2 on day 1. Radiotherapy dose of 46 GY was given in fractions over day 1-30. He tolerated the regimen well with mild irritation of the perineal skin and considerable shrinkage of the tumor. Eight weeks after the completion of chemo radiation a wide excision of the residual tumor involving the left inguinal area, left hemi-scrotectomy with left orchiectomy all the way to the perianal area was performed with simultaneous reconstruction with a Trans pelvic vertical myo-cutaneous rectus abdominis flap (VRAM flap) to cover the large perineal defect. This allowed for primary healing and accelerated rehabilitation. The residual tumor was completely excised and the patient remains free of the disease at 3 years follow up (Figure 5).

The case was discussed in institutional tumor board with surgeons, medical and radiation oncologists. A diverting sigmoid colostomy was performed due to difficulty with peri-anal care and sepsis. After which he received neoadjuvant chemo radiation (Nigro protocol) in the standard regimen and doses. This regimen consisted of preoperative chemotherapy, 5-fluorouracil (1000 mg/m2 per day) by continuous infusion on day 1-4 along with mitomycin C 10 mg/m2 on day 1. Radiotherapy dose of 46 GY was given in fractions over day 1-30. However, he continued to progress with onset of disseminated disease and succumbed to his cancer within three months of his diagnosis.

The patient improved with the multimodal therapy and remains in remission at three years follow up.

The patient tolerated chemo radiation therapy, however continued to progress with metastatic disease into adrenal glands, lungs and inguinal lymph nodes and succumbed to his disease in three months after diagnosis.

GCA is caused by HPV subtypes 6, 11 and occasionally 16, and 18[7]. Patients commonly present with pain, pruritus, bleeding and a slow growing anal mass. Untreated GCA has a propensity to grow into large grotesque masses which are locally destructive and may extend into the pelvic organs and bony structures. These tumors typically have a marked exophytic cauliflower like appearance and histological specimens show marked epidermal hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis. Keratinocytes show vacuolization with abundant cytoplasm (koilocytotic) and a nucleus with prominent nucleoli[6].

Ulcerated lesions should be biopsied to exclude invasive carcinoma. In certain instances, a deep core biopsy of the base is necessary to evaluate histologically the invasion of the basement membrane as the tumor arises in the basal layer of the epidermis infected with the HPV. Deep biopsy may be performed using an 18-gauge needle under mild sedation. This can also be done under CT guidance or endo-ultrasonography. A complete anorectal endoscopic exam is mandatory as some lesions extend proximal into the anal canal. Staging with CT scan or PET scan is useful if invasive cancer is diagnosed and to evaluate the extent of the involvement of the pelvic tissues. A magnetic resonance imaging scan with rectal contrast or endo-coil may also be useful to evaluate extent of perianal sphincter involvement and perirectal tissue involvement. Preoperative EUS may be useful to evaluate rectal and anal sphincter involvement[8]. A multidisciplinary team approach is necessary and should include medical oncologist, radiation oncologist and plastic and reconstructive surgeons. These patients often carry HPV in other muco-cutaneous areas such as penis and oropharynx and require a complete examination. Further risk for other STDs commonly HIV, HSV and Syphilis are higher[6].

Complications such as fistulization, foul odor and secondary infections are common. Large tumors may interfere with defecation; perianal hygiene and sexual activity. Individuals with genital warts from HPV have a long-term increased risk of anogenital and head and neck cancers. SCC may be present in fifty percent of the large tumors[7,9-11].

The pathophysiology of neoplastic transformation from a simple wart in certain individuals remains unclear. Although HPV is nearly ubiquitous, the virus does not cause cancer in majority of patients. Most infections are cleared by the host immune system in 24 mo. Certain host factors such as HIV positivity, smoking, immunosuppression may prevent effective clearance and this may lead to integration of the virus into the host genome. Certain events are fundamental in the neoplastic transformation and include viral persistence, deregulation of viral early gene expression, and host genomic instability[4]. Molecular studies of high risk HPV infections suggest increased expression of HPV proteins E6 and E7 inactivate the host’s tumor suppressor proteins p53 and pRb (retinoblastoma) respectively, keeping the cells in an undifferentiated, dysregulated proliferative state and thus malignant transformation[4,12]. Further these oncoproteins may induce epigenetic changes in host genome including histone modification, chromatin modelling and DNA methylation to affect cellular proliferation, inhibit host immune response and apoptosis to establish persistent infection[4,12-14]. Low risk subtypes HPV 6 and 11 do not integrate in the host genome. It is not clear if increased viral gene expression or inability of the host to mount a cytotoxic immune response changes the oncogenic potential of HPV type 6 and 11, causing progressions of small condyloma to GCA[4,12-14].

The preferred treatment of benign nonmalignant GCA is wide surgical excision with or without additional fulguration to achieve negative margins. These tumors are deep, friable masses and some could be extremely vascularized. The advantage of en bloc wide resection with a 1 cm margin is the ability to histologically examine the entire specimen to ensure clear margins and to evaluate for foci of SCC[15,16]. Surgical excision may be carried out in a single operation or as staged resection if the size of the condyloma is large (> 50% anal circumference) and if anal canal is involved for sphincter preservation. Certain reports have suggested benefits of preoperative selective angio-embolization of the sub segmental feeding branches of the internal iliac arteries to decrease the vascularity and minimize blood loss during the excision of the tumors[17].

Defects can be closed primarily, or left to heal as secondary intention with granulation tissue[16,18]. Larger wounds may require to be closed with a variety of reconstructive skin grafts[16,18]. If the patient has received radiation or anticipating radiation as adjuvant therapy then tissue flap techniques such as V-Y skin flaps, rotational gluteal flaps, and VRAM (Vertical rectus abdominis muscle) myo-cutaneous flap have a higher success rates[19-21]. Simultaneous pelvic reconstructive surgery with excision of the primary tumor decreases the length of recovery, minimizes anal stricture and has better patient satisfaction rates in terms of sexual function and anogenital function. However, reconstruction techniques in the perineum are difficult and may add to further problems with additional wounds such as hematoma, wound infection and dehiscence. Meticulous hemostasis and avoidance of tension is required for optimal outcomes[20,21].

Preoperative the patients should be encouraged to quit smoking and optimize diabetes (glycemic control) and exclude peripheral vascular disease for graft success. Radical procedures such as abdominoperineal resection for these tumors have generally fallen out of favor due to newer techniques and adjuvant therapies. However large perianal lesions with rectal involvement may need fecal diversion and a temporary colostomy[9]. This is primarily done to aid with perianal wound healing as was described in our patient (case 2).

Treatment of SCC associated with perianal GCA has not been standardized due to its rarity. Surgical resection or standard chemo radiation therapy by itself alone has a high recurrence rate. The current standard therapy of primary anal SCC is Nigro protocol consist of combined chemo radiation with mitomycin and 5-fluorouracil followed by radiation therapy[22] with salvage resection limited for residual disease .The use of modern radiotherapy methods, such as intensity modulated radiotherapy can reduce radiation dose and toxicity to normal tissue, while allowing safe administration for higher doses to the gross tumor volume[23]. This permits preservation of anorectal function with improved survival and local control compared with radical resection. This protocol has also been used with success in SCC in GCA treated with preoperative chemo-radiation and followed by radical surgery with success and no recurrences[7,24]. Our patient (case 1) was treated in a similar fashion with preoperative chemo-radiation followed by surgery. No residual cancer was detected in resected specimens and he remains disease free after three years.

Our second case (case 2) did not perform well. Immunosuppression plays a vital role in pathogenesis of anal cancer. Although this patient had a normal CD4 count, his base line immunosuppression and combined antiretroviral therapy may have played a role in rapid progression of this anal cancer. We in our institution treat HIV and non-HIV patients with anal cancer in a similar fashion of standard chemo radiation therapies with surgery reserved for residual disease. No dose reduction was made in either chemotherapy or radiation in these two immunologically different patients. The incidence of HPV induced anal cancer is higher in HIV infected population and continues to rise in the United States especially in the MSM category. It is estimated that incidence of anal cancer in this category to be 80 times higher than men in the general population. The outcomes of anal cancer treatment in HIV positive population is not clear compared to HIV negative individuals. A recent comparative analysis in (total 107 patients) HIV positive and HIV negative cohort showed that HIV positive patients experienced a significantly worse overall survival and colostomy free survival compared to HIV negative cohort. However, there was no difference in the treatment related toxicities in the two cohorts[25,26]. In another study of 142 patients (42 HIV-positive versus 100 HIV-negative) with anal cancer were treated with standard chemo radiotherapy. The outcomes from this study also showed that in the current combined antiretroviral era, tolerance and clinical outcome are similar between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with anal cancer after standard chemo radiotherapy. However, HIV-positive patients had worse 5 year cancer-specific survival[27].

Comprehensive genomic profiling of anal SCC has revealed some commonly mutated genes. These tumors have been show to harbor mutations in EGFR, PIK3CA genes and their signaling pathways could be targetable. Similarly, low mutation rates were noted for KRAS and BRAF mutations[28-30]. These facts made EGFR targeting using the monoclonal antibody (cetuximab) an attractive treatment option in anal cancer however the efficacy of targeted therapy so far is disappointing due to increased toxicities[23].

Further investigations of the role of immune cells and the tumor microenvironment in anal cancers are underway and in the future, may hold promise in the use of immune check point inhibitors alone or in combination with chemo radiation therapy for these tumors[23].

The cure rate for large condyloma with surgical excision alone is reportedly up to 60%; however, recurrence is common and unpredictable[8,9,18]. It is not possible to distinguish between relapse and new infections. All current treatments aim to clear visible lesions however HPV may persist in a latent state and may show resurgence with recurrence rates of 30% to 70% within six months of treatment[18].

Oral, topical and intra-lesional chemotherapeutic modalities have been used with mixed success as adjuvant to surgery or as treatment of recurrences. Typical agents used topically are 5-fluorouracil, Podophyllin 0.5%, trichloroacetic acid, interferon and Imiquimod 5% cream[6]. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen with topical therapy has shown a favorable response in some cases[6]. These nonsurgical modalities are useful as adjunct suppressive therapy. Close surveillance is required following primary surgical therapy as destruction of the entire condyloma cannot be ensured.

Patients with anal cancer following chemo-radiation and surgical excision should be closely monitored every 3 mo initially for local recurrences as well as distant metastases. This requires examination of the ano-rectum under anesthesia, a CT scan of abdomen and pelvis Relapses and recurrences are due to new infections, virus reactivation and failure of complete eradication.

Large anal condylomas are generally caused by low risk HPV 6, 11, however in certain instances can be caused by high risk HPV subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33. Malignant transformation to SCC may occur in large neglected tumors, HIV patients and may be difficult to diagnose. Deep core biopsy, P16 staining and imaging using PET CT scans are necessary to diagnose carcinoma. Due to large size of the tumors a multidisciplinary approach is necessary with combination of neoadjuvant chemo radiation followed by wide excision of these tumors. Large perineal and pelvic defects may need pelvic reconstructive surgery. Patients with HIV and anal cancers carry a poor prognosis. Recurrences are common and should be carefully monitored. Further investigations of the role of the immune cells and the tumor microenvironment in anal cancers are underway and in the future, may hold promise in the use of immune check point inhibitors and other targeted therapies alone or in combination with chemo radiation therapy for these tumors.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aykan NF, Grotz TE, Lin JM, Lin Q, Mastoraki A S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Bian YN

| 1. | Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Statistics at a Glance: Anal cancer. Available from: URL: http://www.seer.cancer.gov. |

| 2. | McQuillan G, Kruszon-Moran D, Markowitz LE, Unger ER, Paulose-Ram R. Prevalence of HPV in Adults Aged 18-69: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;280:1-8. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Doorbar J, Egawa N, Griffin H, Kranjec C, Murakami I. Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev Med Virol. 2015;25 Suppl 1:2-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 58.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Groves IJ, Coleman N. Pathogenesis of human papillomavirus-associated mucosal disease. J Pathol. 2015;235:527-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Steffen C. The men behind the eponym--Abraham Buschke and Ludwig Lowenstein: giant condyloma (Buschke-Loewenstein). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:526-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Assi R, Hashim PW, Reddy VB, Einarsdottir H, Longo WE. Sexually transmitted infections of the anus and rectum. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15262-15268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 7. | Hyacinthe M, Karl R, Coppola D, Goodgame T, Redwood W, Goldenfarb P, Ohori NP, Marcet J. Squamous-cell carcinoma of the pelvis in a giant condyloma acuminatum: use of neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgical resection: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1450-1453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Parikh J, Shaw A, Grant LA, Schizas AM, Datta V, Williams AB, Griffin N. Anal carcinomas: the role of endoanal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in staging, response evaluation and follow-up. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:776-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Trombetta LJ, Place RJ. Giant condyloma acuminatum of the anorectum: trends in epidemiology and management: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1878-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Blomberg M, Friis S, Munk C, Bautz A, Kjaer SK. Genital warts and risk of cancer: a Danish study of nearly 50 000 patients with genital warts. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:1544-1553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chu QD, Vezeridis MP, Libbey NP, Wanebo HJ. Giant condyloma acuminatum (Buschke-Lowenstein tumor) of the anorectal and perianal regions. Analysis of 42 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:950-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vousden KH. Regulation of the cell cycle by viral oncoproteins. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995;6:109-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Durzynska J, Lesniewicz K, Poreba E. Human papillomaviruses in epigenetic regulations. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2017;772:36-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Doorbar J, Quint W, Banks L, Bravo IG, Stoler M, Broker TR, Stanley MA. The biology and life-cycle of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine. 2012;30 Suppl 5:F55-F70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 928] [Cited by in RCA: 960] [Article Influence: 73.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Abbas MA. Wide local excision for Buschke-Löwenstein tumor or circumferential carcinoma in situ. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:313-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Guttadauro A, Chiarelli M, Macchini D, Frassani S, Maternini M, Bertolini A, Gabrielli F. Circumferential anal giant condyloma acuminatum: a new surgical approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:e49-e52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Holubar SD, Yared JE, Forauer A, Balkman J, Pettus J, Bihrle W. Preoperative angioembolization of Bushke-Löwenstein tumor: an innovative, alternative approach to reduce perioperative blood loss for exceptionally large tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:262-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Klaristenfeld D, Israelit S, Beart RW, Ault G, Kaiser AM. Surgical excision of extensive anal condylomata not associated with risk of anal stenosis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:853-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tripoli M, Cordova A, Maggì F, Moschella F. Giant condylomata (Buschke-Löwenstein tumours): our case load in surgical treatment and review of the current therapies. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:747-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mericli AF, Martin JP, Campbell CA. An Algorithmic Anatomical Subunit Approach to Pelvic Wound Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:1004-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Smith HO, Genesen MC, Runowicz CD, Goldberg GL. The rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap: modifications, complications, and sexual function. Cancer. 1998;83:510-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nigro ND. An evaluation of combined therapy for squamous cell cancer of the anal canal. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:763-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Martin D, Balermpas P, Winkelmann R, Rödel F, Rödel C, Fokas E. Anal squamous cell carcinoma - State of the art management and future perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;65:11-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Butler TW, Gefter J, Kleto D, Shuck EH, Ruffner BW. Squamous-cell carcinoma of the anus in condyloma acuminatum. Successful treatment with preoperative chemotherapy and radiation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:293-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang CJ, Sparano J, Palefsky JM. Human Immunodeficiency Virus/AIDS, Human Papillomavirus, and Anal Cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2017;26:17-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Grew D, Bitterman D, Leichman CG, Leichman L, Sanfilippo N, Moore HG, Du K. HIV Infection Is Associated With Poor Outcomes for Patients With Anal Cancer in the Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Era. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:1130-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Martin D, Balermpas P, Fokas E, Rödel C, Yildirim M. Are there HIV-specific Differences for Anal Cancer Patients Treated with Standard Chemoradiotherapy in the Era of Combined Antiretroviral Therapy? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2017;29:248-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chung JH, Sanford E, Johnson A, Klempner SJ, Schrock AB, Palma NA, Erlich RL, Frampton GM, Chalmers ZR, Vergilio J, Rubinson DA, Sun JX, Chmielecki J, Yelensky R, Suh JH, Lipson D, George TJ, Elvin JA, Stephens PJ, Miller VA, Ross JS, Ali SM. Comprehensive genomic profiling of anal squamous cell carcinoma reveals distinct genomically defined classes. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1336-1341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Casadei Gardini A, Capelli L, Ulivi P, Giannini M, Freier E, Tamberi S, Scarpi E, Passardi A, Zoli W, Ragazzini A, Amadori D, Frassineti GL. KRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA status in squamous cell anal carcinoma (SCAC). PLoS One. 2014;9:e92071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Martin V, Zanellato E, Franzetti-Pellanda A, Molinari F, Movilia A, Paganotti A, Deantonio L, De Dosso S, Assi A, Crippa S, Boldorini R, Mazzucchelli L, Saletti P, Frattini M. EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA characterization in squamous cell anal cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2014;29:513-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |