Published online Jun 15, 2018. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i6.137

Peer-review started: March 12, 2018

First decision: April 10, 2018

Revised: April 26, 2018

Accepted: May 30, 2018

Article in press: May 30, 2018

Published online: June 15, 2018

Processing time: 94 Days and 21 Hours

To evaluate the feasibility and safety of trans-anal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) from single institute in China.

A retrospective review was conducted for patients with rectal neoplasia, who underwent TAMIS using single incision laparoscopic surgery-Port from January 2013 till January 2016 by a group of colorectal surgeons from Gastrointestinal Center Unit III, Peking University Cancer Hospital. Patients’ demographic data, surgical related information, post-operational pathology, as well as peri-operative follow-up were all collected.

Twenty-five patients with rectal neoplasia were identified consequently. Complete full-thickness excision was achieved in all cases without conversion. 22 (88%) cases had rectal malignancies [6 were adenocarcinomas and 16 were neuroendocrine tumors (NET)], while 3 patients had adenomas. Mean surgical duration was 61.3 min, and mean post-operative stay were 2.7 d. Post-operational examination demonstrated 5 cases had positive resection margin: 2 adenocarcinoma cases and 1 NET case with positive lateral margin, and the other 2 NET cases with positive basal margin. The curve of operation time for TAMIS cases suggested a minimum of 10 cases for a laparoscopic surgeon proficient with this technique.

TAMIS was demonstrated to be reproducible and safe, with a relatively short learning process for laparoscopic surgeons in selected cases for rectal neoplasia. Long-term oncological outcome needs to be determined by further investigation.

Core tip: Local excision was regarded as the conversional treatment for early stage rectal neoplasia. Recent evidence, however, revealed certain disadvantages. Minimally invasive surgery has been adopted in treating rectal cancer. This study was the first well-documented retrospective trail demonstrating the safety and feasibility of trans-anal minimally invasive surgery. Short-term follow-up showed no serious post-operative complications (over grade IIIa by CD classification), meanwhile, lateral resection margin should be evaluated pathologically and surgeons proficient for laparoscopic surgery would be confident over the learning curve regarding 10 cases.

- Citation: Chen N, Peng YF, Yao YF, Gu J. Trans-anal minimally invasive surgery for rectal neoplasia: Experience from single tertiary institution in China. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2018; 10(6): 137-144

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v10/i6/137.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v10.i6.137

As a challenging area, low rectum has drawn significant attention and caution due to anatomic features. The rates of sphincter-preserving surgery have largely increased, due to the application of neoadjuvant chemoradiation as well as the laparoscopic approach, or both. It, however, is still the fact that colostomy or temporary ileostomy might be necessary in around 10%-30% of the patients with neoplasia in the mid-low third of the rectum[1]. For benign neoplasia or early-stage malignancy located in mid-low rectum, a variety of treatments might be available. Tran-anal local excision is commonly recommended. This approach, however, should be limited to well-selected patients since high-quality oncological excision could not be guaranteed due to exposure and visibility[2,3]. Another meaningful technique might be trans-anal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM), first introduced by Buess et al[4] and considered as an alternative approach, providing acceptable oncological outcome with less postoperative complications and better function, compared with radical excision. Nevertheless, TEM is embedded with certain disadvantages, such as high cost, complexity of the instruments, rather steep learning curve and limited indications, resulting in failure of widespread adoption[5]. Marked advances in instrumental innovation (single port) and technical expertise (laparoscopy) led to the creation of trans-anal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS). At present, two well-designed platforms for TAMIS, the GelPOINT Path and the single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) Port have gained the approval of Food and Drug Administration for use[6,7]. Previous literature has demonstrated that TAMIS might be an alternative choice for rectal lesions, offering several technical advantages compare with TEM: Firstly, with the widespread of laparoscopic surgery, laparoscopic instruments which has been already available could easily be applied in the TAMIS setting, meanwhile the unique apparatus employed by TEM could not be compatible with laparoscopic platform; secondly, the soft platform-SILS Port could provide safer trans-anal access as well as less sphincter traction, compared with rigid channel employed by TEM.

In the present study, SILS Port platform was applied using a standard laparoscopic setting, and the characteristics of patients underwent TAMIS were collected as well as the short-term outcome, aiming to demonstrating the utility of this TAMIS technique with both favorable and unfavorable factors.

This study population consisted of consecutive patients identified from a single institution retrospectively from January 2013 till January 2016. Data from individual patients were reviewed and analyzed. The indications for TAMIS were as follows: benign neoplasia (adenomas over 2.5 cm in diameter); low grade (G1) neuroendocrine tumors with diameter less than 2 cm, and for curative intent stage I rectal cancer with favorable histological features (mri-lymph node negative cT1, with diameter less than 3 cm, moderate to well differentiation, and no mri-lympho-vascular invasion).

Exclusion criteria were patients with certain conditions: invasive rectal tumor (over mri T2 or lymph node positivity), history of inflammatory bowel disease, severe hemorrhoids or anal stricture, fecal incontinence, or with contraindications to general anesthesia. Patients with diagnosis of malignancy underwent preoperative staging with 3-Tesla pelvic MRI or endorectal ultrasound to determine depth of invasion and status of lymph nodes. Standard preoperative imaging, such as computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and baseline blood test for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) were completed before surgical intervention. All TAMIS surgeries were performed in single high-volume tertiary hospital by trained laparoscopic colorectal surgeons under general anesthesia. Technically, TAMIS was a platform whereby standard laparoscopic instruments and cameras were used combined with disposable multi-channel port positioned trans-anally with gas insufflation of the rectum. Full mechanical bowel preparation (polyethylene glycol) was performed, and all patients received preoperative antibiotics which were continued for 1 d in all patients postoperatively.

Trans-anal minimally invasive surgeries were performed using the SILS Port (Covidien-Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN). Pnuemo-rectum was maintained with CO2 insufflation with flow set to 40 L/min and pressure set to 15 mmHg (range, 10-18 mmHg). A high-definition 30º 5 mm or 10 mm camera lens was used in combination with standard laparoscopic graspers and electrocautery or Ethicon Endo-Surgery HARMONIC ACE (Figure 1). After marking the area of resection (Figure 2A), the dissection was started around 5 mm from the lesion margins to obtain a full thickness excision (Figure 2B). The defect was closed in all patients using a running suture of Vicryl 3-0 or V-lock 3-0 (Covidien) (Figure 2C). The surgical specimen were pinned on a cork board and sent fresh for histopathological examination (Figure 2D). Liquid diet was prescribed during post-operational day 1-3. Patients were discharged routinely on the following day of surgery with prolonged stay for special patients, depending on case complexity and occurrence of complications. Data was collected retrospectively in a common database. Complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. The size of specimen, surgery duration, final pathological diagnosis and other peri-operative factors were recorded. Follow up consisted of postoperative visits at 2- and 8-wk after TAMIS, with digital rectal examination.

Summary data were presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and percentages for discrete variables. All statistical tests were two-sided and a P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. The analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM Switzerland Ltd., Zurich, Switzerland).

A total of 25 patients were enrolled in this study, baseline patient demographics and tumor characteristics were summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 51.8, 10 (40%) patients were male, with the mean body mass index 23.9 kg/m2. Five (20%) out of 25 patients had pre-TAMIS local excision before admission. Mean size of the lesions was 1.1 cm (range from 0.5 to 2 cm) in diameter, meanwhile, the mean distance from lesions to anal verge was 8.4 cm (range from 5 to 10 cm). The pathological examination revealed that 3 (12%) patients was diagnosed benign lesions (adenomas), on the other hand, 22 (88%) were malignant, among which 16 with neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and 6 patients with adenocarcinoma (5 patients pT1, and 1 pT3). Positive lymph-vascular invasion was seen in 1 patient, and resection margin was interpreted positive (less than 1 mm) in 5 patients. 18 (72%) patients had their surgeries performed in the Lloyd-Davies position, meanwhile, 7 patients in jackknife position in terms of anterior lesions. There was no intra-operative conversion from TAMIS to laparoscopic radical resection, and the mean duration of TAMIS surgeries was 61.3 min (ranger from 25 to 105 min), with mean blood loss 8.2 mL (range from 5 to 20 mL). There was no operative mortality or serious complication (over grade 3 by Clavien-Dindo grading system), and the mean length of hospital stay was 2.7 d post-operatively. Patients were follow-up more than 3 mo.

| Benign (n = 3) | Malignant1 (n = 22) | All (n = 25) | |

| Mean age, yr (SD) | 55.3 (7.5) | 51.3 (13.8) | 51.8 (13.2) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1 | 8 | 10 (40%) |

| Female | 2 | 14 | 15 (60%) |

| Mean body mass index, kg/m2 (SD) | 23.9 (1.3) | 23.9 (3.0) | 23.9 (2.9) |

| Pre-TAMIS excision | 0 | 5 | 5 (20%) |

| Mean lesion size, cm (SD) | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| Mean distance from anal verge, cm (SD) | 9.3 (0.6) | 8.3 (1.6) | 8.4 (1.6) |

| Final pathology | |||

| Benign | 3 | 3 (12%) | |

| Malignant | 22 (88%) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 6 | 6 (24%) | |

| Mid-high differentiation | 6 | 6 (24%) | |

| Low differentiation | 0 | 0 | |

| T0 (no residual tumor) | 0 | 0 | |

| T1 | 5 | 5 (20%) | |

| T2-3 | 1 | 1 (4%) | |

| NET | 16 | 16 (64%) | |

| Lymph-vascular invasion | 0 | 1 | 1 (4%) |

| Positive margin | 0 | 5 | 5 (20%) |

| Position | |||

| Lloyd-Davies | 3 | 15 | 18 (72%) |

| Jackknife | 0 | 7 | 7 (28%) |

| Mean duration of surgery, min (SD) | 58.0 (37.0) | 61.8 (24.7) | 61.3 (25.5) |

| Mean blood loss, mL (SD) | 5 (0) | 8.6 (4.4) | 8.2 (4.3) |

| Mean length of post-operative stay | 2.3 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.4) |

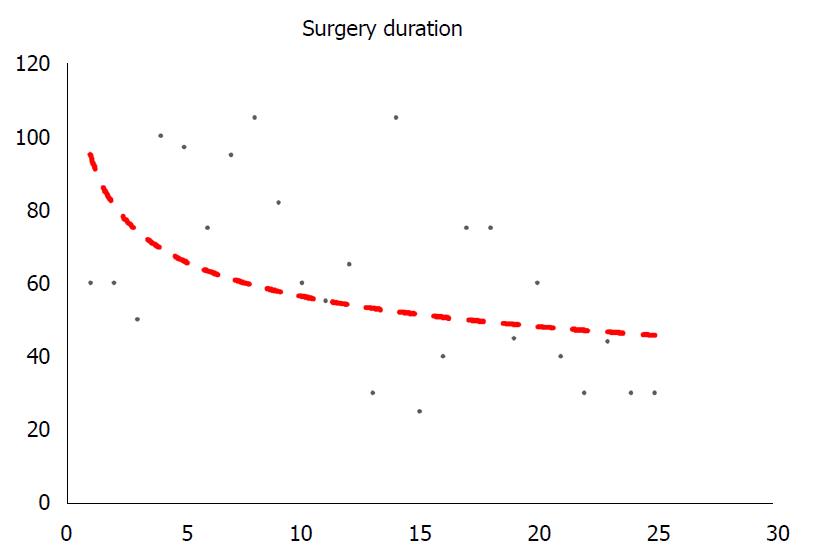

TAMIS surgeries were performed by a group of surgeons proficient with laparoscopic skills. Figure 3 demonstrated the correlation between cases and duration of TAMIS surgeries, indicating the learning curve of this technique. A trend line showed a steep decline in the surgery duration from 1 to 10 cases, and after 10 cases, this line stayed relatively steady.

In this study, we noted that 5 (20%) patients had positive resection margin (defined as less than 1 mm from the cutting edge) by post-operative pathological examination: 2 patients were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma, meanwhile the other 3 were low grade NETs (G1), as shown in Table 2. Interestingly, for cases of adenocarcinoma, positivity occurred at the lateral resection margin, while for cases of NETs, results showed 1 case had positive lateral margin and 2 cases had positive basal margin. All 5 patients with positive margin underwent MDT discussion for further treatment strategies. Finally, for the 2 patients with adenocarcinoma, 1 had curative surgery (low anterior resection), and 1 underwent post-operative chemo-radiation; for the 3 NETs patients, adjuvant imatinib were recommended by oncologists.

| Patients’ No | Age | Gender | BMI (kg/m2) | Distance from anal verge (cm) | Diameter (cm) | Surgery duration (min) | Position | Post-op stay | Type of positive margin | Pathology | Post-op treatment |

| 1 | 58 | 2 | 19.9 | 7 | 2 | 50 | Lloyd-Davies | 1 | Lateral | Adenocarcinoma | Curative surgery |

| 2 | 75 | 2 | 23.2 | 10 | 2 | 60 | Lloyd-Davies | 1 | Basal | NET-G1 | Imatinib |

| 3 | 64 | 2 | 26.1 | 6 | 1.5 | 45 | Lloyd-Davies | 4 | Basal | NET-G1 | Imatinib |

| 4 | 63 | 2 | 20.0 | 10 | 0.5 | 60 | Lloyd-Davies | 2 | Lateral | NET-G1 | Imatinib |

| 5 | 59 | 1 | 24.8 | 8 | 1.5 | 30 | Lloyd-Davies | 3 | Lateral | Adenocarcinoma | Chemo-radiation |

Local excision (LE), as an alternative approach, has been employed under certain circumstances (benign adenomas, early stage adenocarcinomas, and low grade neuroendocrine tumors) for curative intent in rectal neoplasia. However, due to the difficulties in exposure and dissection, LE has been applied only in selected cases[8,9]. Since introduced by Buess et al[4], TEM has progressively become another recommended surgical procedure in clinical practice. The application of TEM, nevertheless, has been notably slow, due to the instrumental obstacles: Surgeons were compelled to operate through a rigid rectoscope, limiting triangulation and the subsequent instrumental manipulation, compared with the standard experience laparoscopically. With the widespread of laparoscopic approach, abdominal and pelvic operations have undergone magnificent changes. Using single-port system with common laparoscopic instruments, trans-anal laparoscopic resection has recently become more accessible. TAMIS, first reported by Atallah et al[10], was a novel trans-anal platform for full-thickness local excision of rectal benign and malignant tumors. TAMIS was more than a local excision technique, based on the laparoscopic platform with curative intent, by adopting the full-thickness resection and wound-sewing under camera and grasper. Several studies with limited cases have been published, demonstrating the better exposure of operative field and easier instrumental manipulation, with the help of high-definition flexible camera and constant gas insufflation[5,7,11,12]. TAMIS settings provided a more precise resection margin and dissection plane, following the full-thickness excision principle.

This paper presented preliminary data from a single-center series of 25 consecutive patients affected by rectal neoplasia, including 22 cases malignancies (6 cases with adenocarcinomas, 16 cases with G1 neuroendocrine tumors) and 3 cases with adenomas, treated by TAMIS. All surgeries were successfully achieved without intra-operative conversion. In the first few cases, TAMIS surgeries were started with considerably better condition, like middle aged, female patients, then all patients meeting the inclusive criteria were suggested afterwards. Therefore, the mean age of enrolled patients was 51.8, and 60% were female due to the safety concerns. Five patients underwent local excision pre-operatively, with positive or unknown margins. In terms of precise orientation of the neoplastic residue or scar, all 5 patients underwent pre-TAMIS endoscopic examination with lesion clipped. Excision was done following the clips. Cases were selected based on the principle of trans-anal local excision by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline version 2017. 1[13]. Post-operational pathology revealed that 3 cases with benign adenomas, while the other 22 were malignant. Among those, 16 (64%) were G1 NETs, and 6 were adenocarcinoma, with 5 T1 tumor and 1 case T3 tumor. No lymph-vascular invasion was seen. Interestingly, for the case with pT3 tumor, pre-operative mri demonstrated T1 (mucosa invasion) while trans-anal ultrasonography showed T1-T2 (putative muscularis invasion), fortunately negative resection margin was achieved by full-thickness resection. Higher risk of recurrence and curative surgery was informed, however, this patient refused surgical intervention due to concerns of anal function, with close follow-up.

The mean diameter of rectal lesions was 1.1 cm, and mean distance from the anal verge was 8.4 cm, indicating the location of mid to high third of the rectum.For cases within 4 cm from the anal verge, retrospective studies noted trans-anal local excision might be more applicable due to several considerations: Firstly, for low rectal lesion, it seems easier for exposure with tractors instead of SILS channel; secondly, the installation of SILS required at least 2 cm normal anal mucosa, resulting in the awkward location-too close from the lesion to the port without guaranteed resection margin. Another concern for the TAMIS technique was the surgical duration, and the majority cases in our studies were finished approximately 60 min with a maximum blood loss of 20 mL, demonstrating the reproducibility of this technique. No severe post-operative complications (Clavien-Dindo 3A or over), such as bleeding or stenosis were observed during the hospital stay and short term (2 and 8 wk) follow-up. Previous literature mentioned the 3.3%-16.8% postoperative complication rate[4,14,15], such as peritoneum perforation, urinary tract infection, subcutaneous emphysema, hemorrhoid thrombosis, etc.

Previous studies of TAMIS were majorly institutional experience with a small amount of cases by retrospective nature. Maya et al[16] demonstrated that 4 cases might be necessary before the skillfulness obtaining by employing the CUSUM curve to assess competence in the surgical techniques of TAMIS. In this study, the routine protocol for TAMIS surgery were established following the literature. From the learning curve as shown above, we noted that surgery duration markedly varied within the first 10 cases and then stayed relatively stable (approximately 60 min), indicating that the proficient skills for TAMIS surgery required a minimal number of 10 cases. For surgeons with proficient laparoscopic technique, TAMIS would be easier since the share of similar instruments.

Previous studies reported that margin positivity was round 4% to 10%[12], according to the so-far largest review on TAMIS. In our study, the rate of positive margin was 20%, which seemed higher than expected. Further reviewing of the data revealed that 2 of 5 cases with positive margin occurred in the first 10 cases, indicating so-called “trial and error” period in TAMIS surgery. Among the following cases, the rates of positive margin greatly lessened. It is important to notice that full thickness resection would merely be guaranteed by dissection of fat tissue in the mesorectum or even penetration into pelvic cavity. Interestingly, it was noted that all these cases were performed with patients in the Lloyd-Davies position, with tumors located either lateral (4/5) or anterior (1/5) wall. It was plausible that patients’ position might had a significant effect on the exposure and dissection of the lesion and the Lloyd-Davies position might not be appropriate for anterior lesions due to the rotated viewing angle[17]. Additionally, correlation between types of positivity with final pathology demonstrated that for adenocarcinoma, 2 of 2 cases had lateral positive margin, while for NETs, 2 of 3 cases had basal positive margin as well as the other 1 with lateral positivity. It is believed that adenocarcinoma, originated from mucosa, would have intraluminal mucosa infiltration[13]; conversely, NET has more mysterious features with various types of infiltration[18]. The 3mm resection margin was recommended by “National Comprehensive Cancer Network” (NCCN) for the principle of local excision in terms of curative intent[19], as implemented in our study. However, trans-anal local excision was performed using a variety of other standards of resection margin, from 5 mm to 10 mm[20,21]. It is speculated that positivity of resection margin might be decreased if the 5 mm (or 10 mm) margin applied, indicating for rectal malignancy treated by the TAMIS surgery, an enlarged resection margin might be safer. On the other hand, the defect resulted from enlarged resection, might raise higher requirement for laparoscopic sewing, regarding longer incision, higher suture tension, increased probability of post-operative stricture or scarring[22]. Whether enlarged margin would result in survival benefit might still be controversial and need more high quality of evidence.

For neoplasia located on the anterior wall of upper third of rectum (above the peritoneal reflection), full-thickness resection inevitably results in the penetration into peritoneal cavity. In our study, there were 4 (16%) patients had the entering into peritoneal cavity intra-operatively with neoplasia located in the anterior wall. It is believed that full-thickness excision is mandatory when local excision performed for malignancy due to the probability containing an invasive component[23]. However, not all published literature reported[24]. It has been demonstrated that a partial thickness excision would result in a dramatic increase in the rates of positive margin[25], leading to enhanced risk of loco-regional recurrence.

Though with the well-established settings, TAMIS has its technical shortcomings. Firstly, it seems easier for instrumental manipulation compared with TEM, however, difficulties occurred with rectal masses which located over 10 cm from the anal verge, due to the existence of these transverse rectal folds as well as the physiological curvature of the pelvis. Secondly, the firm fixation of SILS Port platform to the anus required a minimal of 3-4 cm anal canal, therefore it would be difficult to get TAMIS done within 3-4 cm from the anal verge[15]. Thirdly, through the single port apparatus, laparoscopic instruments roughly oriented in parallel, resulting in the failure of triangulation, making free bending and rotating more difficult. Fourthly, general anesthesia, as applied in our TAMIS surgeries, yet had the problem of peristalsis under autonomic innervation intraoperatively, which was a disturbing factor for steady surgical fields. For better relaxation effect, additional methods, such as low sacral anesthesia might worth a try.

This study has its own limitations by its retrospective nature, relatively small cohort size and selected cases. The short-term outcome demonstrated that TAMIS might be a feasible technique in terms of full-thickness resection and minimal sphincter injury. Recent studies demonstrated that total mesorectal excision (TME) by using the platform of TAMIS was increasingly performed, leading the advance in the management of distal rectal cancer[26]. Long-term oncological safety needs to be investigated with further follow-up.

In summary, TAMIS is a feasible method of performing full thickness resection for rectal lesions with acceptable short-term outcome. Surgeon proficient with laparoscopic surgery would able to manage this technique after a training period of approximately 10 cases. TAMIS might be suggested as one of the alternative choices for the treatment of lesions located in the mid rectum of selected patients.

Local excision is regarded as the standard treatment for mid-low rectal neoplasia, including benign tumors and early-stage malignancy. Due to the disadvantages in exposure, high quality of local excision could not be well guaranteed, though trans-anal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) could merely provide solutions in certain conditions. Therefore, it is essential to call for another technique to fill the gap in-between. Recently, trans-anal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) has been introduced as an alternative choice for rectal lesions.

TAMIS surgery was reported by literature with relatively small amount of cases, however, there has been no published data on TAMIS surgery on the Chinese population. The safety and feasibility of TAMIS is still lack of evidence.

This study was designed to investigate the utility of TAMIS technique with both favorable and unfavorable factors.

TAMIS surgery was done by a standard laparoscopic platform (SILS Port). Patients’ characteristics, surgery duration, pathological diagnosis and post-operative complications (Clavien-Dindo classification) were collected.

The research findings, their contributions to the research in this field, and the problems that remain to be solved should be described in detail. Among 25 patients enrolled, 10 (40%) patients were male, with the mean age of the patients 51.8 and the mean body mass index 23.9 kg/m2. Mean diameter of the lesions was 1.1 cm (range from 0.5 to 2 cm) and the mean distance to anal verge was 8.4 cm (range from 5 to 10 cm). 3 (12%) patients was diagnosed benign lesions (adenomas), 22 (88%) were malignancies (16 with neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and 6 with adenocarcinoma (5 patients pT1, and 1 pT3). Positive resection margin (less than 1 mm) was revealed in 5 patients and lymph-vascular invasion was seen in 1 patient. Eighteen (72%) TAMIS surgeries were performed in the Lloyd-Davies position, with the rest in jackknife position. The mean duration of was 61.3 min (ranger from 25 to 105 min), with mean blood loss 8.2 mL (range from 5 to 20 mL) and no conversion to laparoscopic surgery. No operative mortality or serious complication (over grade 3 by Clavien-Dindo grading system), and the mean length of hospital stay was 2.7 d post-operatively. A laparoscopic surgeon would be proficient to perform TAMIS surgery with around 10 cases.

TAMIS could be safe and feasible technique to early stage rectal neoplasia. Laparoscopic surgeons would be proficient for TAMIS with approximately 10 cases. TAMIS might provide an alternative method with conventional laparoscopic apparatus, compared with TEM. This study demonstrated the first piece of evidence of peri-operative data and short-term outcome in patients treated with TAMIS in Chinese tertiary hospital. TAMIS is a safe method treating early stage rectal neoplasia. Surgical position might have a significant effect on the positivity of resection margin, and Lloyds-Davies position might not be appropriate for anterior lesions. TAMIS could offer full-thickness resection and minimal sphincter injury. TAMIS might be an alternative choice for patients with early stage rectal neoplasia.

TAMIS could be feasible by utilizing laparoscopic apparatus. For lesion located anteriorly, it might be better with jackknife position. It might be essential to know the rate of positivity concerning resection margin with larger number of cases prospectively; and it worth a try to use TAMIS in down-stage rectal cancer patients underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiation for re-staging and curative intent. A prospective clinical trial might be a good choice.

We greatly appreciate the following staff members who contributed to this work: Professor Ai-Wen Wu, Professor Jun Zhao, Professor Ming Li, Professor Zhong-Wu Li in Peking University Cancer Hospital.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Amin S, Facciorusso A, Musquer N S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8406] [Cited by in RCA: 8961] [Article Influence: 689.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Garcia-Aguilar J, Renfro LA, Chow OS, Shi Q, Carrero XW, Lynn PB, Thomas CR Jr, Chan E, Cataldo PA, Marcet JE, Medich DS, Johnson CS, Oommen SC, Wolff BG, Pigazzi A, McNevin SM, Pons RK, Bleday R. Organ preservation for clinical T2N0 distal rectal cancer using neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and local excision (ACOSOG Z6041): results of an open-label, single-arm, multi-institutional, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1537-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hallam S, Messenger DE, Thomas MG. A Systematic Review of Local Excision After Neoadjuvant Therapy for Rectal Cancer: Are ypT0 Tumors the Limit? Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:984-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Buess G, Theiss R, Hutterer F, Pichlmaier H, Pelz C, Holfeld T, Said S, Isselhard W. [Transanal endoscopic surgery of the rectum - testing a new method in animal experiments]. Leber Magen Darm. 1983;13:73-77. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Clancy C, Burke JP, Albert MR, O’Connell PR, Winter DC. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery versus standard transanal excision for the removal of rectal neoplasms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:254-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Noura S, Ohue M, Miyoshi N, Yasui M. Transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) with a GelPOINT® Path for lower rectal cancer as an alternative to transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM). Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;5:148-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McLemore EC, Weston LA, Coker AM, Jacobsen GR, Talamini MA, Horgan S, Ramamoorthy SL. Transanal minimally invasive surgery for benign and malignant rectal neoplasia. Am J Surg. 2014;208:372-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marijnen CA. Organ preservation in rectal cancer: have all questions been answered? Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e13-e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sugarbaker PH, Corlew S. Influence of surgical techniques on survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:545-557. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Atallah S, Albert M, Larach S. Transanal minimally invasive surgery: a giant leap forward. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2200-2205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Albert MR, Atallah SB, deBeche-Adams TC, Izfar S, Larach SW. Transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) for local excision of benign neoplasms and early-stage rectal cancer: efficacy and outcomes in the first 50 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:301-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee L, Burke JP, deBeche-Adams T, Nassif G, Martin-Perez B, Monson JRT, Albert MR, Atallah SB. Transanal Minimally Invasive Surgery for Local Excision of Benign and Malignant Rectal Neoplasia: Outcomes From 200 Consecutive Cases With Midterm Follow Up. Ann Surg. 2018;267:910-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Graham RA, Hackford AW, Wazer DE. Local excision of rectal carcinoma: a safe alternative for more advanced tumors? J Surg Oncol. 1999;70:235-238. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Atallah SB, Albert MR. Transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) versus transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM): is one better than the other? Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4750-4751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lee TG, Lee SJ. Transanal single-port microsurgery for rectal tumors: minimal invasive surgery under spinal anesthesia. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:271-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Maya A, Vorenberg A, Oviedo M, da Silva G, Wexner SD, Sands D. Learning curve for transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1407-1412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Buchs NC, Pugin F, Volonte F, Hagen ME, Morel P, Ris F. Robotic transanal endoscopic microsurgery: technical details for the lateral approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1194-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Soga J. Early-stage carcinoids of the gastrointestinal tract: an analysis of 1914 reported cases. Cancer. 2005;103:1587-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | You YN, Baxter NN, Stewart A, Nelson H. Is the increasing rate of local excision for stage I rectal cancer in the United States justified?: a nationwide cohort study from the National Cancer Database. Ann Surg. 2007;245:726-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dias AR, Nahas CS, Marques CF, Nahas SC, Cecconello I. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: indications, results and controversies. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:105-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hakiman H, Pendola M, Fleshman JW. Replacing Transanal Excision with Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery and/or Transanal Minimally Invasive Surgery for Early Rectal Cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2015;28:38-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cataldo PA, O’Brien S, Osler T. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a prospective evaluation of functional results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1366-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ramirez JM, Aguilella V, Gracia JA, Ortego J, Escudero P, Valencia J, Esco R, Martinez M. Local full-thickness excision as first line treatment for sessile rectal adenomas: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2009;249:225-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Martin-Perez B, Andrade-Ribeiro GD, Hunter L, Atallah S. A systematic review of transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) from 2010 to 2013. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:775-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bach SP, Hill J, Monson JR, Simson JN, Lane L, Merrie A, Warren B, Mortensen NJ; Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (TEM) Collaboration. A predictive model for local recurrence after transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:280-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Atallah S, Albert M, DeBeche-Adams T, Nassif G, Polavarapu H, Larach S. Transanal minimally invasive surgery for total mesorectal excision (TAMIS-TME): a stepwise description of the surgical technique with video demonstration. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:321-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |