Published online Dec 15, 2018. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i12.487

Peer-review started: September 11, 2018

First decision: October 5, 2018

Revised: October 15, 2018

Accepted: November 7, 2018

Article in press: November 8, 2018

Published online: December 15, 2018

Processing time: 95 Days and 1.4 Hours

To compare the outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for gastric neoplasms using Clutch Cutter (ESD-C) or other knives (ESD-O).

This was a single-center retrospective study. Gastric neoplasms treated by ESD between April 2016 and October 2017 at Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center were reviewed. Multivariate analyses and propensity score matching were used to reduce biases. Covariates included factors that might affect outcomes of ESD, including age, sex, underlying disease, anti-thrombotic drugs use, tumor location, tumor position, tumor size, tumor depth, tumor morphology, tumor histology, ulcer (scar), and operator skill. The treatment outcomes were compared among two groups. The primary outcome was ESD procedure time. Secondary outcomes were en bloc, complete, and curative resection rates, and adverse events rates including perforation and delayed bleeding.

A total of 155 patients were included in this study; 44 pairs were created by propensity score matching. Background characteristics were quite similar among two groups after matching. Procedure time was significantly shorter for ESD-C (median; 49 min) than for ESD-O (median; 88.5 min) (P < 0.01). However, there was no significant difference in treatment outcomes between ESD-C and ESD-O including en bloc resection rate (100% in both groups), complete resection rate (100% in both groups), curative resection rate (86.4% vs 88.6%, P = 0.730), delayed bleeding (2.3% vs 6.8%, P = 0.62) and perforation (0% in both groups).

ESD-C achieved shorter procedure time without an increase in complication risk. Therefore, ESD-C could become an effective ESD option for gastric neoplasms.

Core tip: Propensity score matching was performed to compare the outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for gastric neoplasms using Clutch Cutter or other knives in this single-center retrospective study. Forty-four pairs were matched in this study. ESD using Clutch Cutter achieved shorter procedure time without an increase in complication risk (median procedure time; 49 min vs 88.5 min, P < 0.01). Therefore, ESD using Clutch Cutter could become an effective ESD option for gastric neoplasms.

- Citation: Hayashi Y, Esaki M, Suzuki S, Ihara E, Yokoyama A, Sakisaka S, Hosokawa T, Tanaka Y, Mizutani T, Tsuruta S, Iwao A, Yamakawa S, Irie A, Minoda Y, Hata Y, Ogino H, Akiho H, Ogawa Y. Clutch Cutter knife efficacy in endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2018; 10(12): 487-495

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v10/i12/487.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v10.i12.487

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is the standard treatment for gastrointestinal tract tumors including gastric neoplasms, achieving a higher rate of en bloc resection and low rates of local recurrence even for large and ulcerated lesions, as compared with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)[1]. However, more advanced technical skills and greater experience are needed in ESD because of the longer procedure time and high risk of complications including bleeding and perforation[1]. Although various types of endo-knife including needle-type knife and insulated-tip knife were invented and used in ESD, this remains a challenging procedure and there is no consensus on the best knife to be used[2-5].

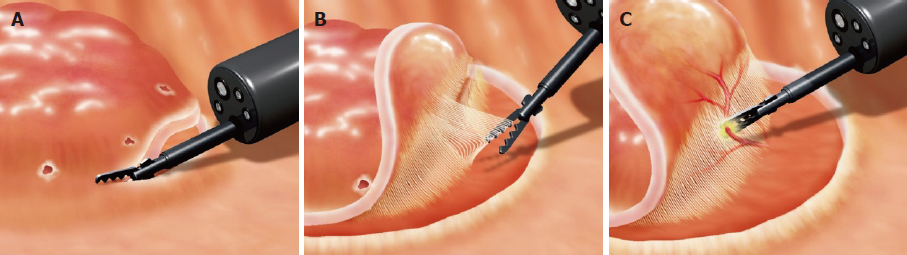

Clutch Cutter (DP2618DT, Fujifilm Medical, Tokyo, Japan; Figure 1) was invented as a scissor-type device for ESD, which allows for grasping of the targeted tissue and its subsequent cut with an electrosurgical unit[6]. This procedure is similar to the technique of a standard bite biopsy, which is a common procedure during routine endoscopy. Furthermore, Clutch Cutter allows re-grasping of the tissue anytime during ESD, which may prevent miscutting and perforation. Therefore, Clutch Cutter may contribute to easier and safer ESD than other endo-knives. ESD with Clutch Cutter (ESD-C) may then become an option of endo-knife for ESD. Favorable outcomes of ESD-C have been reported, including in a large single-center study with single arm trial[7-9]. However, few reports exist showing the comparison between scissors-type and non-scissors-type knives in the technical outcomes of ESD, which have been limited to non-experts in inclusion criteria[10,11]. The advantage of scissor-type knife in ESD is controversial at present because comparative studies are still lacking.

We retrospectively compared the technical outcomes of ESD-C for gastric neoplasms with those of ESD with other knives (ESD-O) by using propensity score matching analysis, which compensated for differences in extraneous factors including baseline characteristics[2]. We hypothesize that the outcomes using ESD-C will be superior to those of ESD-O.

This was designed as a retrospective, observational cohort study, which was conducted based on the ESD databases at a single-center, Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center (Fukuoka, Japan). These cases represented a consecutive and unselected cohort. The protocol of this study was developed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center on November 2017 (No. 201711050).

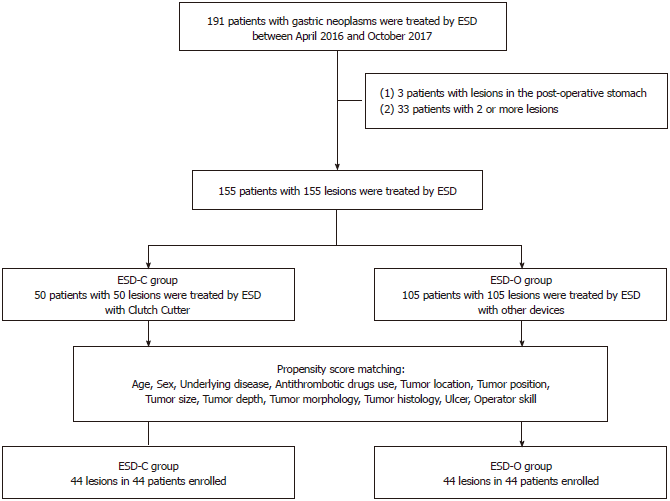

We enrolled 191 consecutive patients with gastric neoplasms treated by ESD between April 2016 and October 2017 at the Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center. Three patients were excluded from analysis for previously having undergone gastric surgery. Furthermore, 33 patients were excluded because two or more lesions were simultaneously resected. Finally, 155 patients were analyzed in this study. We classified the patients into two groups: one group included patients treated by ESD-C and the other group included patients treated by ESD-O. Either IT Knife2 (KD-611L, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or Splash M-Knife (DN-D2718A; HOYA Corp., Pentax, Tokyo, Japan) was mainly used in the patients enrolled between April 2016 and March 2017, while Clutch Cutter was mainly used in the patients enrolled between April 2017 and October 2017. The flow chart of the patients enrolled in the present study is shown in Figure 2.

All patients were admitted at Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center. All ESD procedures were carried out using a GIF-Q260J (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a CO2 insufflation system. VIO 300D (ERBE Elektromedizin, GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) was used as the electrical power source. The ESD procedure was described in detail in previous reports[7,12,13]. In brief, marking dots were made 2 mm outside the lesion. A mixture of 4% hyaluronic acid and normal saline with a small amount of indigo carmine and epinephrine (0.001 mg/mL) was injected into the submucosa. After lifting the lesion, mucosal incision was conducted circumferentially using cutting and coagulation (Figure 3A). Once the circumferential mucosal incision was completed, submucosal dissection of the lesion was performed using cutting and coagulation (Figure 3B). Injection was added during dissection when needed. Prophylactic coagulation for visible vessels or hemostasis for active bleeding was conducted using endo-knives or hemostatic forceps (Figure 3C). When using Clutch Cutter, cutting was conducted by Endo Cut Mode (effect 1, duration 4, interval 1), while coagulation was conducted by Soft Coagulation Mode (80-100 W, effect; 5-6 in VIO300D) or Forced Coagulation Mode (30 W, effect 2). In this study, operators with an experience of performing at least 50 ESD procedures were defined as experts, while those who had performed less than 50 ESD procedures were defined as trainees. As a result, 4 operators were defined as experts and 5 as trainees in this study. All experts were familiar with using each device since they had used each device at least 10 times before this study.

ESD specimens were immediately stretched and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. The specimens were serially sectioned perpendicularly at 2-3 mm intervals. Then, histological type, depth of invasion, tumor size, lymphatic/vascular invasion, and resection margin were assessed. The pathological curability of the specimens was evaluated based on the Japanese Gastric Cancer Classification[14].

The primary outcome of this study was the procedure time during ESD, which was defined as the time from the start of marking to the completion of dissection. En bloc resection rate, complete resection rate, curative resection rate, and the rate of complications (delayed bleeding and perforation) were evaluated as secondary outcomes. En bloc resection was defined as resection in one piece. Complete resection was defined as en bloc resection with the lateral and vertical resection margins free of neoplasm. Curative resection was evaluated according to the guideline[15]. Delayed bleeding was defined as clinical evidence of bleeding after ESD, requiring endoscopic hemostasis or blood transfusion. Perforation was diagnosed if mesenteric fat or the intra-abdominal space was observed during ESD procedure or free air was detected on chest and abdominal radiographs or computed tomography scans after ESD. All patients were given a proton pump inhibitor or potassium competitive acid blocker for a minimum of 4 wk.

Background characteristics were not equal among two groups. Previous studies have reported some factors associated with the difficulty or complication of the ESD procedure, which may affect outcomes of this study[16-22]. Therefore, we adopted propensity score matching analysis to reduce bias. Logistic regression of the following factors with ESD device (Clutch Cutter vs other endo-knives) and calculation of propensity score were conducted: age (≥ 75 vs < 75 years old), sex (male vs female), underlying disease (presence vs none), anti-thrombotic drugs use (continuation vs not receiving or discontinuation), tumor location (upper third of the stomach vs middle or lower third), tumor position (lessor curvature of the stomach vs others), tumor size (> 20 mm vs ≤ 20 mm), tumor depth (mucosa vs submucosa), tumor morphology (flat or depressed vs others), tumor histology (differentiated type vs undifferentiated type), ulcer (scar) (presence vs absence), and operator skill (expert vs trainee). Underlying disease included cardiomyopathy, liver cirrhosis, and chronic kidney disease. Nearest neighbor matching in a 1:1 ratio from the ESD-C and ESD-O groups was made in calipers (0.12) with a width equal to 0.25 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score. Baseline characteristics and outcomes were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test for categorial data, the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data with non-normal distributions, and a t test for continuous data with normal distribution. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro13.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, i.e., C statistic, was estimated to be 0.681, which indicated good predictive power. Propensity score matching created 44 pairs in this study. We compared two groups by using the absolute standardized differences (ASD) before and after matching to assess the propensity score balance. After matching, all ASDs ranged within 1.96√2/n, indicating that the characteristics were well-balanced[23].

The background characteristics of 155 patients enrolled in this study are shown in Table 1. Patients in the ESD-C group had a significantly higher rate of undifferentiated adenocarcinoma than those in the ESD-O group (10.0% vs 0.95%; P = 0.014). The median tumor size of patients in ESD-C group was significantly smaller than that of patients in the ESD-O group (13.5 mm vs 18.0 mm; P = 0.027).

| ESD-C n = 50 | ESD-O n = 105 | P value | ASD | |

| Age, yr | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 73.1 ± 8.55 | 72.75 ± 8.04 | 0.8062 | 0.0422 |

| Median (range) | 74.0 (46–91) | 73.0 (52–91) | 0.5803 | |

| Sex (n) | ||||

| Male | 39 | 71 | 0.2561 | 0.2350 |

| Female | 11 | 34 | ||

| Underlying disease, positive, n (%) | 18 (36.0) | 29 (27.6) | 0.3501 | 0.1810 |

| Anti-thrombotic drugs (n) | ||||

| None or discontinuation | 48 | 102 | 0.6581 | 0.0623 |

| Continuation | 2 | 3 | ||

| Tumor location (n) | ||||

| Upper third | 9 | 17 | 0.8201 | 0.0481 |

| Middle or lower third | 41 | 88 | ||

| Tumor position (n) | ||||

| Lessor | 21 | 57 | 0.7311 | 0.2670 |

| Others | 29 | 48 | ||

| Morphology (n) | ||||

| Flat or depressed | 29 | 63 | 0.8621 | 0.0407 |

| Others | 21 | 42 | ||

| Histology (n) | ||||

| Undifferentiated | 5 | 1 | 0.01414 | 0.4060 |

| Others | 45 | 104 | ||

| Tumor size (mm) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 16.89 ± 12.65 | 20.90 ± 13.30 | 0.0762 | 0.3090 |

| Median (range) | 13.5 (3–67) | 18.0 (3–82) | 0.02734 | |

| Tumor depth (n) | ||||

| Mucosa | 44 | 91 | 1.0001 | 0.0401 |

| Submucosa | 6 | 14 | ||

| Ulceration positive, n (%) | 7 (14.0) | 22 (21.0) | 0.3811 | 0.1840 |

| Operator skill | ||||

| Experts | 34 | 73 | 0.8541 | 0.0329 |

| Trainees | 16 | 32 | ||

Matching factors between two groups after propensity score matching are shown in Table 2. No significant differences were found in any matching factors.

| ESD-C n = 44 | ESD-O n = 44 | P value | ASD | |

| Variable matching between groups | ||||

| Age, yr; mean ± SD | 73.16 ± 8.59 | 71.11 ± 8.81 | 0.2732 | 0.2360 |

| Sex: Male/female | 8/36 | 6/38 | 0.7721 | 0.1250 |

| Underlying disease: No/yes | 28/16 | 29/15 | 11 | 0.0476 |

| Anti-thrombotic drugs: No/yes | 2/42 | 3/41 | 11 | 0.0983 |

| Tumor location: Upper third/others | 7/37 | 2/42 | 0.2501 | 0.3810 |

| Tumor position: Lessor/others | 19/25 | 21/23 | 0.8311 | 0.0914 |

| Morphology: Flat or depressed/others | 25/19 | 28/16 | 0.6631 | 0.1400 |

| Histology: Undifferentiated/others | 0/44 | 0/44 | - | 0 |

| Tumor size, mm: mean ± SD | 16.89 ± 12.65 | 20.90 ± 13.30 | 0.0762 | 0.3090 |

| Tumor depth: Mucosa/submucosa | Jun-38 | Jun-38 | 11 | 0 |

| Ulceration, positive | 6 (13.6%) | 4 (9.1%) | 0.7391 | 0.1440 |

| Operator skill: Expert/trainee | 14/30 | 14/30 | 11 | 0 |

Treatment outcomes after matching are shown in Table 3. A significantly shorter procedure time was observed for ESD-C than for ESD-O in the adjusted comparison (49.0 min vs 88.5 min; P < 0.001). En bloc resection rates and complete resection rates were 100% in both groups. All ESDs were completed without perforation. Curative resection rates were similar between the two groups. The delayed bleeding rates of ESD-C tended to be lower than those of ESD-O, but these rates did not reach statistical significance (2.3% vs 6.8%, P = 0.62).

The present study is the first to show that the technical outcomes of ESD-C are superior to those of ESD-O for the endoscopic treatment of gastric neoplasms regardless of technical expertise, as shown by the propensity score matching analysis.

Currently, a wide variety of ESD devices is available. These devices are roughly classified into two types: scissor-type knives or non-scissor-type knives. The scissor-type knives commonly used in ESD include Clutch Cutter, SB knife, and SB knife Jr, while non-scissor-type knives mainly include IT Knife2, Dual knife, Flush knife, and Splash M-Knife. However, it is yet to be determined which type of knife is superior, scissor-type or non-scissor-type.

It has been reported that the scissor-type knives reduced the technical difficulty of gastrointestinal ESD for unexperienced as well as expert endoscopists[24,25]. Rescue usage of the SB Jr knife has been reported to increase the self-completion rate of ESD of colorectal neoplasms using the Flush knife (63% in the SB Jr knife group vs 39% in the Flush knife only group; P = 0.03), without increasing the procedure time (59 min vs 51 min; P = 0.14)[11]. In other studies, however, ESD-C was reported to be a time-consuming procedure compared with ESD with non-scissor-type knives, especially when performed by unexperienced endoscopists[26,27]. Therefore, we carried out this study using a propensity score matching analysis to determine which was superior, ESD-C or ESD-O. We found that ESD-C achieved significantly shorter procedure time than ESD-O, indicating that ESD-C is a time-saving rather than a time-consuming procedure. Clutch Cutter might reduce the technical difficulties in gastric ESD similarly to those in colorectal ESD, which might have contributed to the reduction in procedure time. The scissors-type knives were invented several years after the invention of non-scissors-type knives[4-6]. In general, ESD experts tended to use non-scissors-type knives rather than scissors-type knives. In previous studies on the usefulness of ESD-C, the ESD-C procedures were conducted mainly by trainees rather than experts. In this study, however, ESD procedures were performed by 4 experts and 5 trainees. After propensity score matching, up to 68.2% of ESD procedures were conducted by experts, which might explain the discrepancy in the outcomes between the present and previous studies. ESD with scissor-type knives is being widely used not only by trainees but also by experts.

Both delayed bleeding and perforation are major complications of ESD. In the present study, delayed bleeding occurred in only 1 case with ESD-C while in 3 cases with ESD-O after propensity score matching, although the results were not statistically significant. Moreover, the delayed bleeding rate was 2.0% in ESD-C before propensity score matching (data not shown), which was lower than previously reported delayed bleeding rates[15]. Although it was unknown why delayed bleeding occurs, during ESD-C, hemostasis was conducted by grasping and coagulation, similar to the procedure by hemostatic forceps, which may contribute to the reduction in the delayed bleeding rate. On the other hand, no perforation occurred in ESD-C before propensity score matching in this study. By contrast, perforation occurred in one case of ESD-O before matching (data not shown), although this case was excluded after propensity score matching. Although the number of patients undergoing ESD-C was smaller than that of patients undergoing ESD-O, ESD-C might be a safer procedure than ESD-O. In ESD-C, tissue grasping and lifting were conducted before coagulation or cutting, which could reduce heat conduction to the muscular layer, contributing to the decreased risk of perforation. In terms of safety, it was reported that ESD-C could be preferred over ESD-O for elderly patients with some comorbidities[28]. In the present study, over 90% (46/50 before matching, 41/44 after matching) of patients were aged 65 years or older; furthermore, over 40% (22/50 before matching, 20/44 after matching) of patients were aged 75 years or older. No patient experienced worsening of general condition or developed any severe complications. However, further studies are required to clarify whether ESD-C is safer than ESD-O. In addition, ESD-C has been recently used not only for ESD but also for other endoscopic procedures such as endoscopic treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum and endoscopic necrosectomy for pancreatic necrosis[29-31]. In the future, Clutch Cutter could be widely applied in additional endoscopic procedures.

This study had several limitations. First, this was a single-center retrospective study. Therefore, the sample size was relatively small. There might be a selection bias because lesions in the ESD-C group were significantly smaller than those in the ESD-O group and had significantly higher rate of undifferentiation in histology evaluation. Second, only 9 endoscopists conducted ESD. Therefore, a multicenter trial should be carried out to validate this outcome. Third, in some ESD procedures conducted by trainees, experts occasionally assisted in the procedure, which might affect the outcomes of this study. Fourth, we grouped other devices together, including needle-type and insulated-tip knives, for comparison with Clutch Cutter. Future studies are needed to compare each knife individually with Clutch Cutter. Fifth, there was a possibility of an institutional learning curve. We cannot compensate for this bias because the Clutch Cutter was used mainly in the latter phase of this study; other devices were used mainly in former phase of this study, which may also affect outcomes.

In conclusion, ESD-C achieved shorter procedure time than ESD-O without an increase in complication rates. Therefore, ESD-C could become one of the best endoscopic procedure options in ESD for gastric neoplasms.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is the standard treatment for early gastric neoplasms with negligible lymph node metastasis. However, it is a complex and difficult procedure. Many types of endo-knives have been invented and developed to improve the ESD procedure.

The Clutch Cutter is a novel scissor-type endo-knife, which may contribute to facilitating the ESD procedure. However, few studies have compared the technical outcomes of each knife.

The aim of this study was to compare the technical outcomes between ESD with the Clutch Cutter and ESD with other devices.

Patients with early gastric neoplasms treated by ESD at Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center between April 2016 and October 2017 were reviewed. ESD was performed using the Clutch Cutter (ESD-C group) or other devices (ESD-O group). Propensity score matching analysis was conducted to compensate for confounding differences between the two groups that may affect the outcomes. After matching, the technical outcomes of ESD were compared among the two groups.

A total of 155 patients were included and 44 pairs were matched. ESD with the Clutch Cutter achieved a significantly shorter procedure time (median, 49 min vs 88.5 min, P < 0.001). The other technical outcomes and complication rates were similar among the two groups.

The Clutch Cutter contributed to shortening the ESD’s procedure time. ESD with the Clutch Cutter could be an effective option in ESD with endo-knives for early gastric neoplasms.

This was a single-center, retrospective study with a relatively small number of ESD cases. Therefore, further large-scale, randomized, prospective studies are needed.

We thank Shuichi Itonaga and Kota Bussaka (Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center) for their assistance in data collection.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ciocalteu A, Tanabe S S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Park YM, Cho E, Kang HY, Kim JM. The effectiveness and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2666-2677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Esaki M, Suzuki S, Hayashi Y, Yokoyama A, Abe S, Hosokawa T, Ogino H, Akiho H, Ihara E, Ogawa Y. Splash M-knife versus Flush Knife BT in the technical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bhatt A, Abe S, Kumaravel A, Vargo J, Saito Y. Indications and Techniques for Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:784-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kodashima S, Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, Ichinose M, Omata M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasia: experience with the flex-knife. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2006;69:224-229. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ohkuwa M, Hosokawa K, Boku N, Ohtu A, Tajiri H, Yoshida S. New endoscopic treatment for intramucosal gastric tumors using an insulated-tip diathermic knife. Endoscopy. 2001;33:221-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Akahoshi K, Akahane H, Murata A, Akiba H, Oya M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection using a novel grasping type scissors forceps. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1103-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Akahoshi K, Motomura Y, Kubokawa M, Gibo J, Kinoshita N, Osada S, Tokumaru K, Hosokawa T, Tomoeda N, Otsuka Y. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Cancer using the Clutch Cutter: a large single-center experience. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E432-E438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Akahoshi K, Kubokawa M, Gibo J, Osada S, Tokumaru K, Yamaguchi E, Ikeda H, Sato T, Miyamoto K, Kimura Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric adenomas using the clutch cutter. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;9:334-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akahoshi K, Honda K, Motomura Y, Kubokawa M, Okamoto R, Osoegawa T, Nakama N, Kashiwabara Y, Higuchi N, Tanaka Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection using a grasping-type scissors forceps for early gastric cancers and adenomas. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:24-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nagai K, Uedo N, Yamashina T, Matsui F, Matsuura N, Ito T, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K. A comparative study of grasping-type scissors forceps and insulated-tip knife for endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E654-E660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yamashina T, Takeuchi Y, Nagai K, Matsuura N, Ito T, Fujii M, Hanaoka N, Higashino K, Uedo N, Ishihara R. Scissor-type knife significantly improves self-completion rate of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: Single-center prospective randomized trial. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:322-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Akahoshi K, Akahane H, Motomura Y, Kubokawa M, Itaba S, Komori K, Nakama N, Oya M, Nakamura K. A new approach: endoscopic submucosal dissection using the Clutch Cutter® for early stage digestive tract tumors. Digestion. 2012;85:80-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamamoto H, Kawata H, Sunada K, Satoh K, Kaneko Y, Ido K, Sugano K. Success rate of curative endoscopic mucosal resection with circumferential mucosal incision assisted by submucosal injection of sodium hyaluronate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:507-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yokoyama T, Kamada K, Tsurui Y, Kashizuka H, Okano E, Ogawa S, Obara S, Tatsumi M. Clinicopathological analysis for recurrence of stage Ib gastric cancer (according to the second English edition of the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:372-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chung IK, Lee JH, Lee SH, Kim SJ, Cho JY, Cho WY, Hwangbo Y, Keum BR, Park JJ, Chun HJ. Therapeutic outcomes in 1000 cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: Korean ESD Study Group multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1228-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 429] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim JH, Nam HS, Choi CW, Kang DH, Kim HW, Park SB, Kim SJ, Hwang SH, Lee SH. Risk factors associated with difficult gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: predicting difficult ESD. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:1617-1626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Imagawa A, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Kato J, Kawamoto H, Fujiki S, Takata R, Yoshino T, Shiratori Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: results and degrees of technical difficulty as well as success. Endoscopy. 2006;38:987-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Libânio D, Costa MN, Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Risk factors for bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:572-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Choi IJ, Kim CG, Chang HJ, Kim SG, Kook MC, Bae JM. The learning curve for EMR with circumferential mucosal incision in treating intramucosal gastric neoplasm. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:860-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yoshida M, Kakushima N, Mori K, Igarashi K, Kawata N, Tanaka M, Takizawa K, Ito S, Imai K, Hotta K. Learning curve and clinical outcome of gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection performed by trainee operators. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3614-3622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hong KH, Shin SJ, Kim JH. Learning curve for endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:949-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083-3107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3915] [Cited by in RCA: 4389] [Article Influence: 274.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Akahoshi K, Akahane H. A new breakthrough: ESD using a newly developed grasping type scissor forceps for early gastrointestinal tract neoplasms. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Oka S, Tanaka S, Takata S, Kanao H, Chayama K. Usefulness and safety of SB knife Jr in endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Dig Endosc. 2012;24 Suppl 1:90-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Akahoshi K, Okamoto R, Akahane H, Motomura Y, Kubokawa M, Osoegawa T, Nakama N, Chaen T, Oya M, Nakamura K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early colorectal tumors using a grasping-type scissors forceps: a preliminary clinical study. Endoscopy. 2010;42:419-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yamamoto S, Uedo N, Ishihara R, Kajimoto N, Ogiyama H, Fukushima Y, Yamamoto S, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Iishi H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer performed by supervised residents: assessment of feasibility and learning curve. Endoscopy. 2009;41:923-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Otsuka Y, Akahoshi K, Yasunaga K, Kubokawa M, Gibo J, Osada S, Tokumaru K, Miyamoto K, Sato T, Shiratsuchi Y. Clinical outcomes of Clutch Cutter endoscopic submucosal dissection for older patients with early gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;9:416-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 29. | Ishaq S, Sultan H, Siau K, Kuwai T, Mulder CJ, Neumann H. New and emerging techniques for endoscopic treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum: State-of-the-art review. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:449-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | González N, Debenedetti D, Taullard A. Endoscopic retreatment of Zenker’s diverticulum using novel endoscopic scissors - The Clutch Cutter device. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2017;109:669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Neumann H, Löffler S, Rieger S, Kretschmer C, Nägel A. Endoscopic therapy of Zenker’s diverticulum using a novel endoscopic scissor - the Clutch Cutter device. Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1 UCTN:E430-E431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |