INTRODUCTION

In 1842, Rokitansky described a disease phenomenon known today as amyloidosis[1]. Amyloidosis has been classified as primary or secondary, being predisposed by infection, inflammation, or systemic disease. It is a process involving the deposition of proteinaceous fibrillar material in a pattern that is typically systemic, occasionally organ-limited, and very rarely as solitary localized mass. The latter, commonly referred to as tumoral amyloidosis, can often masquerade as a neoplasm and has been reported to have occurred in nearly every organ or tissue including the brain, stomach, esophagus, jejunum, heart, cervical spine, thoracic spine, urethra, bladder, popliteal fossa, as a nodule on a lower extremity, breast, parotid gland, and submandibular gland[2-17]. Gottfried et al[18] reported amyloidoma of the trigeminal nerve mimicking as a tumor of the cavernous sinus.

Amyloidoma of the stomach was described in 1956 by Intriere and Brown[19]. In 1978 the first autopsy-proven case of tumoral amyloidosis was reported[20]. Only a few more cases have been published since then. In the case below, we describe tumoral amyloidoma confined to the stomach and duodenum in a male who had been in remission for Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL).

CASE REPORT

A 72 year-old black male with a history of NHL sought medical attention after a three day course of diffuse abdominal pain. The pain was exacerbated by seating upright. The patient also complained of early satiety and a 60-lb weight loss over the last year prior to presentation. He denied dysphagia, odynophagia, or change in bowel habits or character of stool. The patient had a colonoscopy as well as an upper endoscopy six years ago at an outside institution which he stated was unremarkable.

The patient was treated for his NHL five years ago, with six rounds of status-post six rounds of cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, prednisone chemotherapy, and currently was in remission chemotherapy, and was believed to be in remission upon presentation. There was no family history of gastrointestinal disorders or malignancy. His only medication was pregabalin which was prescribed to him for lower extremity pain and weakness. The patient had immigrated from Barbados and had been living in United States for the past 40 years. He had been a life-long smoker and consumed a moderate amount of alcohol daily.

His physical exam was pertinent for mild pallor and generalized abdominal tenderness, but no abdominal masses or adenopathy was appreciated. On laboratory evaluation, a urinalysis and culture was significant for Beta Hemolytic Strep Group B urinary tract infection, but negative for Bence Jones protein. Complete blood count and iron panel revealed anemia of chronic disease. Electrolyte and hepatic panels were unremarkable.

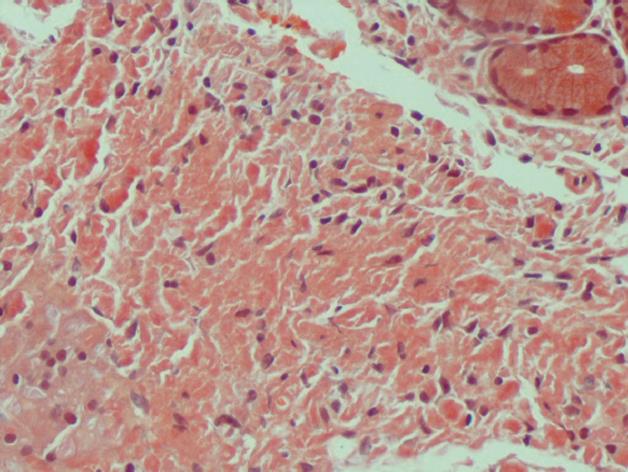

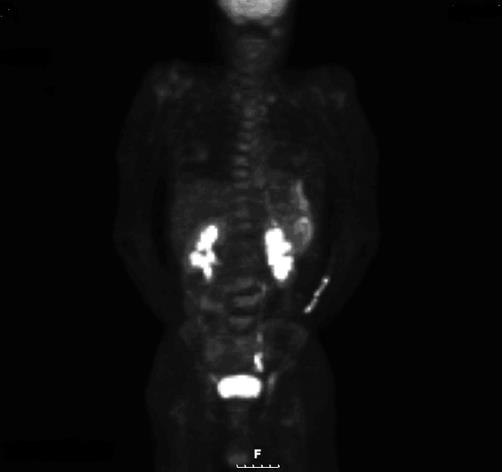

On admission, a computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed thickening and calcification of the gastric wall with associated pneumatosis, as well as a 1 cm pedunculated mass in the proximal duodenum (Figure 1). No focal hepatic masses or biliary ductal dilatations were seen. He subsequently underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), whereby a large circumferential friable, ulcerated, nodular mass was seen from the gastro-esophageal junction to the body of the stomach. A large non bleeding ulcer was appreciated in the fundus of the greater curvature. Lastly, a non-bleeding 3 cm polyp was noted in post bulbar area of the duodenum (Figure 2). Biopsies were obtained and, due to their appearance under light microscopy with Hematoxylin and Eosin stain, were stained with Congo red (Figure 3). This showed a classic green birefringence under polarized light, consistent with tumoral amyloidosis. A positron emission tomography scan revealed diffuse gastric mucosa uptake compatible with gastric malignancy but no hypermetabolic neoplastic foci elsewhere (Figure 4).

Figure 1 CAT scan of the abdomen revealed thickening and calcification of the gastric wall with associated pneumatosis, as well as a 1 cm pedunculated mass in the proximal duodenum.

Figure 2 On esophagogastroduodenoscopy, a non bleeding 3 cm polyp was noted in the post-bulbar area of the duodenum.

Figure 3 Under light microscopy, gastric biopsy appears salmon-colored when stained with Congo Red.

Figure 4 PET scan revealed diffuse gastric mucosa uptake compatible with gastric malignancy but no hypermetabolic neoplastic foci elsewhere.

After medically controlling his abdominal pain, the patient was discharged home with a plan to observe his condition periodically.

DISCUSSION

Multiple diagnostic modalities have been employed in verifying amyloidosis. The lesion, when subjected to hematoxylin-eosin stain, will appear as diffuse deposits of acellular, amorphous eosinophilic material on light microscopy. When stained with Congo red, green birefringence is observed under polarized light. Amyloid is also described as having a beta pleated sheet arrangement on radiographic diffraction.

Balázs[21] in 1981 performed the first electron microscopy study on amyloidoma biopsies from the stomach corpus. They found three dominant cells: plasma cells, fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts. Mucus secretion was impaired. The cytoplasm of mucin producing cells was filled with a filamentous substance which replaced the organelles. Myofibroblasts located within the amyloid mass were observed to show active secretion of microfilaments.

With regards to pathogenesis, the formation of amyloid was posited to result from an inadequate immune response to an antigenic stimulus resulting in decreasing mucus production in gastric mucosa while increasing the population of myofibroblasts[21]. Hamidi Asl et al[22] observed monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains as the principal composition of amyloidomas in the respiratory and urinary tract, thus implicating local monoclonal plasma cell proliferation as the underlying cause of the disease process. Regarding amyloidoma of the small bowel, Saindane et al[23] theorized that amyloid deposition into mesenteric vasculature induces a focal ischemia leading to wall thickening, edema, hemorrhage, and ulceration thus predisposing to significant amyloid deposition.

There is a paucity of cases in the literature of localized amyloid depositions in the stomach to date, and the physical descriptions of such cases varies. Amyloidosis of the stomach has been described as flat circular lesions with a fine granular appearance[24], diffuse thickening of the gastric wall with a tendency to bleed[20,25], irregularly-shaped, soft, mural tumors[21], and even as a gastric ulcer with heaped up, friable edges, masquerading as malignancy[26]. In addition, loss of rugal folds and antral narrowing have been reported[27,28]. Our patient’s amyloidoma appear as a large circumferential friable mass that was ulcerated, nodular, edematous, and bled easily on contact.

Being such a rare phenomenon, consensus on treatment and the prognosis for amyloidoma, particularly in the gut, is quite limited. In 1978, Ikeda et al[20] reported a 68 year-old female with epigastric distress who was worked up for what was believed to be a gastric tumor. The patient was eventually treated with a partial gastrectomy and Billroth I anastomosis only to be finally diagnosed with a localized amyloidosis of the stomach. The patient died ten months later of unrelated causes and, at autopsy, no amyloid deposits were found in the remnant stomach or anywhere else in her body. Another patient underwent subtotal gastrectomy and clearance of perigastric lymph nodes as this was believed to be essential in preventing postoperative recurrence of amyloid deposition[26]. Solanke et al[29] described a 48-year-old woman with progressive dysphagia and weight loss who was found to have an amyloidoma of the distal esophagus. She was treated with an esophageal bypass using a segment of colon. Suri et al[10] suggested that localized amyloidosis had a good prognosis as compared to systemic amyloidosis with treatment simply by complete resection of the lesion itself. A favorable prognosis was given also to amyloidoma of the pulmonary system[30,31].

Kahi et al[4] offered a more conservative approach of careful long-term observation alone as the management of amyloidoma of the esophagus. In one case where gastric amyloidoma presented with dyspepsia, the treatment consisted solely of a proton pump inhibitor and a prokinetic medication[24]. No further treatment was offered and the patient was asymptomatic at a 10-mo follow-up.

In regards to our patient, it is unknown whether the amyloidoma in the gut was primary or secondary to his prior history of NHL. At the time of presentation, he was in remission from NHL after receiving standard chemotherapy treatment and an EGD one year prior to diagnosis of NHL excluded any visible pathology of the stomach. Nonetheless, Krishnan et al[32] found half of their subjects with soft tissue amyloidomas had a lymphoproliferative disorder. Therefore, does our observation represent relapse of his prior disease process? No studies exist to answer this question. What implication, if any, does this have for future patients who are being surveyed for NHL relapse? Since most of the literature supports observation or at most, resection of the amyloid mass, does our patient require the same or does this case warrant future treatment? Should the re-institution of chemotherapy for NHL be considered? Only the contribution of similar cases to the literature will elucidate the matter.