Published online Jul 10, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i13.472

Peer-review started: March 7, 2016

First decision: April 6, 2016

Revised: April 14, 2016

Accepted: May 7, 2016

Article in press: May 9, 2016

Published online: July 10, 2016

Processing time: 117 Days and 0.8 Hours

A 52-year-old female presented to our clinic after accidentally ingesting a push-through pack (PTP). After determining that the PTP was present in the stomach, we successfully and safely removed it endoscopically by using a handmade endoscopic hood fashioned from a cut endotracheal tube. Foreign body ingestion is a common clinical problem, and most ingested foreign bodies pass spontaneously. However, the ingestion of sharp objects, such as PTPs, increases the risk of complications, and urgent endoscopy is recommended to remove such objects. Previous studies have reported the use of other devices, both commercial and handmade, for the safe endoscopic removal of foreign bodies. The novel design of our handmade hood for the removal of the PTP, which was fashioned from a cut endotracheal tube, was beneficial in terms of maintaining a wide visual field, patient safety and tolerance, and easy preparation compared to previously reported commercial and handmade devices. It may be a viable and safe device for the retrieval of PTPs and other sharp foreign bodies.

Core tip: Here, we report the successful and safe endoscopic removal of a push-through pack (PTP) from the stomach using a handmade endoscopic hood fashioned from a cut endotracheal tube. This novel design was beneficial in terms of maintaining a wide visual field, patient safety and tolerance, and easy preparation, compared to previously reported commercial or handmade devices. It may be a viable and safe device for the retrieval of PTPs and other sharp foreign bodies.

- Citation: Tateno Y, Suzuki R. Cut endotracheal tube for endoscopic removal of an ingested push-through pack. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(13): 472-476

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i13/472.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i13.472

Foreign body ingestion is commonly encountered in clinical practice, and most (≥ 80%) foreign bodies pass spontaneously without the need for intervention[1]. However, the ingestion of sharp and pointed objects, such as animal/fish bones, needles, and push-through packs (PTPs), increases the risk of perforation or obstruction by as much as 35%[1].

PTPs are commonly used in Japan[2] and South Korea[3] for the packaging of drugs. PTPs have three or four sharp edges that, when they are accidentally ingested, can perforate the small intestine[4]. Therefore, PTPs that have passed into the stomach or proximal duodenum should be immediately retrieved endoscopically, provided this procedure can be performed safely[1]. Flexible endoscopy is the ideal choice for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in the management of upper gastrointestinal foreign bodies, with a reported success rate of over 95% and minimal complications[5]. The risk of mucosal injury during retrieval can be minimized during extraction by orienting the sharp points of the object with handmade and commercial accessory instruments[1], such as an overtube[3], a latex hood over the endoscope[6], a latex glove[7], or a condom[8].

Here, we report the successful and safe endoscopic removal of a PTP from the stomach using a novel handmade endoscopic hood fashioned from a cut endotracheal tube.

A 52-year-old female with no medical history of dementia or psychological impairment presented to our clinic due to the accidental ingestion of a PTP 2 h previously. She complained of sharp intermittent pain in the substernal region. She was alert, with a temperature of 36.5 °C, blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg, regular pulse of 96 bpm, and respiration of 18 breaths/min; there were no signs of abdominal tenderness or peritoneal irritation. Abdominal computed tomography showed no signs of perforation or the presence of a PTP. These findings, coupled with the fact that she had swallowed the PTP only 2 h before presentation, led us to suspect that the PTP was lodged in her esophagus or stomach. Urgent endoscopy revealed the PTP in the stomach (Figure 1).

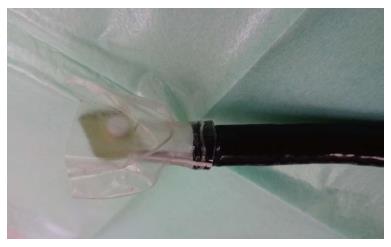

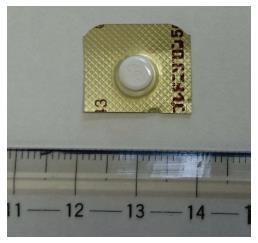

We did not possess an overtube or commercial device for the removal of foreign bodies because our clinic is located on a remote island in Japan and is not sufficiently equipped for such medical emergencies. Therefore, to remove the PTP, a handmade hood protector was fashioned from a cut endotracheal tube (Teleflex, Endosoft 8.5; Willy Rüsch GmbH, Kernen im Remstal, Germany) (Figures 2 and 3) with an internal diameter of 8.5 mm, an external diameter of 11.3 mm, and a cuff composed of polyvinyl chloride. The hood was fastened to the distal end of the endoscope (GIF-H260; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), which was 9.8 mm in diameter, without the use of rubber bands or string. The cut cuff used to cloak the PTP edges was approximately 30 mm in diameter (Figure 4). The scope was inserted without the use of general anesthesia or sedation, and the PTP was captured using biopsy forceps, pulled into the cut cuff of the handmade hood, avoiding the inside of the tube (Figure 5), and extracted. All four edges of the PTP were cloaked with the cuff during retrieval (Figure 6). The size of the impacted PTP was 19 mm × 16 mm (Figure 7). Following PTP removal, endoscopic evaluation of the esophagus showed no signs of mucosal damage, ulceration, bleeding, or perforation. The complete endoscopic procedure took only 20 min; the inspection time was thought to be acceptable without sedation. The patient was immediately discharged after endoscopy without any complications.

We successfully removed an ingested PTP from the stomach using a novel endoscopic hood fashioned from a cut endotracheal tube. A wide variety of handmade and commercial devices have been used for the endoscopic removal of foreign bodies[1,3,6,7-11], including an overtube[3], a latex protector hood fitted over an endoscope[6], a latex glove[7], and a condom[8]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of the removal of an ingested foreign body using a handmade endoscopic hood cut from an endotracheal tube.

Our novel endoscopic hood was fashioned by cutting an endotracheal tube (CET hood), which consisted of a stalk-like tube and a petal-like cuff. This characteristic shape offers some advantages in the retrieval of PTPs. First, a CET hood can maintain a good visual field and wide working space. Previous reports showed that a transparent cap and overtube improve the visual field and working space[3,12]. The CET hood contained a tube that resembled the stalk of a flower and offered advantages similar to those of a transparent cap attached to the end of the endoscope. Although we were concerned that the cuff would obscure the visual field, the tube had adequate length and sufficient hardness to resist hood collapse and maintain the visual field. Second, the CET hood was able to cloak the PTP, which had a wider diameter than the endoscope. The endoscopic removal of a PTP with a wider diameter than the internal diameter of the overtube will occasionally fail because the uncloaked edges can cause mucosal injury during retrieval[3,8]. The internal diameter of the overtube used in this case was approximately 15 mm[3]. Even if the diameter of the PTP exceeds 15 mm, as in our patient (19 mm), the flexibility of the tube may enable the operator to bend and pull the overtube[3]. However, care should be taken not to cause mucosal injury by pinching the mucosa between the PTP and overtube. A bell-shaped simple latex protector hood[6] or handmade hood constructed from a condom[8] have been reported to be more suitable devices in cases that require a wide cover hood. The CET hood used in this case also contained a wide covering protector approximately 30 mm in diameter, which offered the same advantages as these devices. Third, the level of difficulty in the insertion and removal of an endoscope fitted with a CET hood was not different from that observed with typical endoscopic inspection. Lin[8] reported the use of a condom protector hood for the successful removal of a PTP without complications, which exhibited good tolerance due to the thinness of the material. Endoscopic treatment using a CET hood minimizes patient discomfort during its insertion through a narrow segment, such as the pharynx, because the cut cuff of a CET hood is sufficiently flexible to pass through the pharynx. In addition, a CET hood is suitable for emergency endoscopy due to the simple method of preparation and availability in an inadequately equipped medical institution.

Other articles have described the use of a handmade protector or hood for the endoscopic removal of foreign bodies[1,3,6,7-11]. Handmade devices must be easily and swiftly prepared for use in emergency endoscopy[1,11]. The preparation of a CET hood is relatively simple because it requires only the cutting and fitting of the apparatus to the endoscope. Of course, commercial devices are the simplest to use and prepare[6]; however, not all medical institutions have these devices on hand. Although the ingestion of foreign bodies can occur anywhere, it is impractical for all medical institutions, especially those in developing countries or remote areas, to maintain a sufficient supply of commercial devices for the retrieval of foreign bodies. Therefore, under such circumstances, a CET hood can be easily fashioned from an endotracheal tube, which is readily available in most medical institutions.

However, the level of protection provided for the removal of sharp foreign bodies, such as needles or bones, should be determined in future studies. Further research should compare materials with varying cuff thicknesses (approximately 0.05 mm)[13] compared to surgical gloves (approximately 0.29 mm)[8] and a latex hood (2 mm), such as that manufactured by Kimberly/Ballard Medical Products (Draper, UT, United States)[8].

In conclusion, we report the successful and safe endoscopic removal of a PTP from a patient’s stomach using a handmade endoscopic hood fashioned from a cut endotracheal tube. This novel handmade device offered some advantages compared to previously reported commercial and handmade devices and may be an alternative device for the retrieval of PTPs and other sharp foreign bodies.

A 52-year-old female presented after accidentally ingesting a push-through pack (PTP).

Accidental ingestion of PTP in the stomach.

Accidental ingestion of PTP in the esophagus or small intestine.

All laboratory tests were within normal limits.

Abdominal computed tomography showed no signs of perforation or the presence of a PTP, and urgent endoscopy revealed the PTP in the stomach.

PTP was successfully and safely removed endoscopically using a handmade endoscopic hood fashioned from a cut endotracheal tube.

Previous studies reported other devices, both commercial and handmade, for safe endoscopic removal of foreign bodies.

PTPs are commonly used in Japan and South Korea for packaging of drugs. PTPs have three or four sharp edges and, when accidentally ingested, can perforate the small intestine.

The authors’ novel handmade device conveyed some advantages, as compared to previously reported commercial and handmade devices, and can be an alternative device for retrieval of PTPs and other sharp foreign bodies.

The paper is an interesting case report.

P- Reviewer: Akere A, Farhat S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Fisher LR, Fukami N. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1085-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Kumagai M, Ikeda K, Oshima T, Nakatsuka S, Takasaka T. A press-through-pack in the larynx. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1997;183:293-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Seo YS, Park JJ, Kim JH, Kim JY, Yeon JE, Kim JS, Byun KS, Bak YT. Removal of press-through-packs impacted in the upper esophagus using an overtube. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5909-5912. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Hashizume T, Tokumaru AM, Harada K. Small intestine perforation due to accidental press-through package ingestion in an elderly patient with Lewy body dementia and recurrent cardiopulmonary arrest. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015212723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yao CC, Wu IT, Lu LS, Lin SC, Liang CM, Kuo YH, Yang SC, Wu CK, Wang HM, Kuo CH. Endoscopic Management of Foreign Bodies in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract of Adults. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:658602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bertoni G, Sassatelli R, Conigliaro R, Bedogni G. A simple latex protector hood for safe endoscopic removal of sharp-pointed gastroesophageal foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:458-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kao LS, Nguyen T, Dominitz J, Teicher HL, Kearney DJ. Modification of a latex glove for the safe endoscopic removal of a sharp gastric foreign body. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:127-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lin LF. Condoms used to assist difficult endoscopic removal of impacted upper esophageal foreign bodies. Advances in Digestive Medicine. 2016;3:24-27. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ginsberg GG. Management of ingested foreign objects and food bolus impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:33-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Smith MT, Wong RK. Foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17:361-382, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chiu KW, Lu LS, Wu TC, Chiou SS. Novel low-cost endoscopic cap for esophageal foreign objects: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hyun JJ, Chun HJ, Keum B, Seo YS, Kim YS, Jeen YT, Lee HS, Um SH, Kim CD, Ryu HS. Alternative salvage technique for removing large sharp foreign body near upper esophageal sphincter. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:e48-e52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lorente L, Blot S, Rello J. New issues and controversies in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:870-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |