Published online Oct 10, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i14.1135

Peer-review started: April 30, 2015

First decision: July 25, 2015

Revised: July 31, 2015

Accepted: September 7, 2015

Article in press: September 8, 2015

Published online: October 10, 2015

Processing time: 175 Days and 6.3 Hours

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has become an important therapeutic modality for biliary and pancreatic disorders. Perforation is one of the most feared complications of ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy. A MEDLINE search was performed from 2000-2014 using the keywords “perforation”, “ERCP” and “endoscopic sphincterotomy”. All articles including more than nine cases were reviewed. The incidence of ERCP-related perforations was low (0.39%, 95%CI: 0.34-0.69) with an associated mortality of 7.8% (95%CI: 3.80-13.07). Endoscopic sphincterotomy was responsible for 41% of perforations, insertion and manipulations of the endoscope for 26%, guidewires for 15%, dilation of strictures for 3%, other instruments for 4%, stent insertion or migration for 2% and in 7% of cases the etiology was unknown. The diagnosis was made during ERCP in 73% of cases. The mechanism, site and extent of injury, suggested by clinical and radiographic findings, should guide towards operative or non-operative management. In type I perforations early surgical repair is indicated, unless endoscopic closure can be achieved. Patients with type II perforations should be treated initially non-operatively. Non-operative treatment includes biliary stenting, fasting, intravenous fluid resuscitation, nasogastric drainage, broad spectrum antibiotics, percutaneous drainage of fluid collections. Non-operative treatment was successful in 79% of patients with type II injuries, with an overall mortality of 9.4%. Non-operative treatment was sufficient in all patients with type III injuries. Surgical technique depends on timing, site and size of defect and clinical condition of the patient. In conclusion, diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion and clinical and radiographic findings. Whilst surgery is usually indicated in patients with type I injuries, patients with type II or III injuries should be treated initially non-operatively. A minority of them will finally require surgical intervention.

Core tip: Perforation is one of the most feared complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic sphincterotomy. The incidence of ERCP-related perforations is low (0.39%) with an associated mortality of 7.8%. Endoscopic sphincterotomy is responsible for 41% of perforations and endoscope manipulations for 26%. The mechanism, site and extent of injury, suggested by clinical and radiographic findings, should guide towards operative or non-operative management. Classification into types permits a tailored approach to management. Whilst surgery is usually indicated in patients with type I injuries, patients with type II or III injuries should be treated initially non-operatively. A minority of them will finally require surgical intervention.

- Citation: Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Polydorou A. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related perforations: Diagnosis and management. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(14): 1135-1141

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i14/1135.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i14.1135

In the era of minimally invasive therapy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with endoscopic sphincterotomy has become an important therapeutic modality for the treatment of biliary and pancreatic disorders. Although considered as a safe procedure, it is associated with complications such as pancreatitis, bleeding and perforation. The incidence of ERCP-related complications is 5%-10% and the overall mortality 0.1%-1%[1-5].

Perforation is one of the most feared complications of ERCP and sphincterotomy. In a review of 21 prospective studies[6], addressing ERCP complications, between 1987-2003, perforations occurred in 101 patients (0.6%, 95%CI: 0.48-0.72) with a perforation related mortality of 9.90% (95%CI: 3.96-15.84).

Traditionally, the standard treatment for iatrogenic duodenal perforations has been early surgical repair. Recently, non operative management of ERCP-related perforations has increased. However, it is difficult to evaluate the efficacy of different treatments, because of the rarity of the complication and there is no consensus for optimal management.

This review aims to evaluate the incidence, diagnosis and treatment of ERCP-related perforations.

A MEDLINE search was performed from 2000-2014 using the keywords “perforation”, “ERCP” and “endoscopic sphincterotomy”. All articles including more than nine cases were reviewed. No randomized controlled trial could be identified.

There are two proposed classifications of ERCP-related perforations. In 1999, Howard et al[7] classified perforations into three distinct types: type I, guidewire perforation; type II, periampullary perforation; type III, duodenal perforation remote from the papilla. In 2000 Stapfer et al[8] classified ERCP-related perforations into four types, based on the mechanism, anatomical location and severity of injury, which may predict the need for surgery. The Stapfer classification is the most commonly used and it divides perforations into: Type I, lateral or medial wall duodenal perforation; type II, perivaterian injuries; type III, distal bile duct injuries related to guidewire-basket instrumentation and type IV, retroperitoneal air alone. Type IV is questionable and it is not a true perforation. Due to the excess compression of air in the duodenum, air bubbles can leak through the sphincterotomy area outside the duodenal lumen, into the retroperitoneal space. The presence of retroperitoneal air is a common finding after endoscopic sphincterotomy. CT scan, when used routinely after ERCP and sphincterotomy, may detect retroperitoneal air in 13% to 29% of patients[9,10]. In the absence of symptoms, it has no clinical significance and these patients do not require any further intervention.

Reviewing 18 studies[8,11-27], between 2000-2014 (mainly retrospective), addressing only ERCP-related perforations, including 142847 patients, the incidence was 0.39% (95%CI: 0.34-0.69). According to Stapfer classification, type I counted 25%, type II 46% and type III 22%. The overall mortality was 7.8% (95%CI: 3.80-13.07) (Table 1).

| Ref. | Design | n | Perforations (%) | Types1 | Mortality (%) | |||||

| I | II | III | IV | |||||||

| Assalia et al[11], 2007 | Prosp | 3104 | 22 | (0.70) | 2 | 17 | 2 | 1 | (4.5) | |

| Avgerinos et al[12], 2009 | Retro | 4358 | 15 | (0.34) | 9 | 3 | 1 | 3 | (20) | |

| Dubecz et al[13], 2012 | Retro | 12232 | 11 | (0.08) | 7 | 3 | 1 | 2 | (18) | |

| Enns et al[14], 2002 | Case control | 9314 | 33 | (0.35) | 5 | 13 | 15 | 1 | (3) | |

| Fatima et al[15], 2007 | Retro | 12427 | 75 | (0.60) | 8 | 26 | 35 | 6 | 5 | (6.6) |

| Jin et al[16], 2013 | Retro | 22998 | 59 | (0.26) | 17 | 36 | 6 | 5 | (8.4) | |

| Kayhan et al[17], 2004 | Retro | 3124 | 17 | (0.54) | 2 | 15 | - | - | ||

| Kim et al[18], 2011 | Retro | 7638 | 13 | (0.17) | 4 | 5 | 4 | 0 | (0) | |

| Kim et al[19], 2012 | Retro | 11048 | 68 | (0.61) | 13 | 31 | 22 | 4 | (5.8) | |

| Knudson et al[20], 2008 | Retro | 4919 | 32 | (0.65) | 6 | 11 | 7 | 0 | (0) | |

| Kwon et al[21], 2012 | Retro | 8381 | 53 | (0.63) | 21 | 24 | 8 | 3 | (5.6) | |

| Li et al[22], 2012 | Retro | 8504 | 16 | (0.45) | 7 | 5 | 4 | 0 | (0) | |

| Mao et al[23], 2008 | Retro | 2432 | 9 | (0.37) | 8 | 1 | 0 | (0) | ||

| Miller et al[24], 2013 | Retro | 1638 | 27 | (1.60) | 5 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 9 | (33) |

| Morgan et al[25], 2009 | Retro | 12817 | 24 | (0.18) | 12 | 12 | 1 | (4.1) | ||

| Polydorou et al[26], 2011 | Retro | 9880 | 44 | (0.44) | 7 | 30 | 5 | 2 | 2 | (4.5) |

| Stapfer et al[8], 2000 | Retro | 1413 | 14 | (0.99) | 5 | 6 | 3 | 2 | (14) | |

| Wu et al[27], 2006 | Retro | 6620 | 30 | (0.45) | 5 | 11 | 7 | 5 | (16) | |

| Total | 142847 | 562 | (0.39) | 143 (25%) | 261 (46%) | 124 (22%) | 43/545 | (7.8) | ||

A multivariate analysis to reveal risk factors was performed in two studies[4,14]. Precut, Billroth II gastrectomy and intramural injection of contrast medium were significant risk factors for retroperitoneal duodenal perforation by Loperfido et al[4]. In Enns et al[14]’s study, factors existing prior to ERCP which predicted perforation included sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and a dilated common bile duct. Predictive factors related to ERCP itself included duration of procedure, biliary stricture dilation and performance of a sphincterotomy. Precut didn’t reach statistical significance in that study.

The mechanism of injury is mentioned in 573 patients from 18 studies[8,11-15,17-23,25-29] (Table 2). Endoscopic sphincterotomy was responsible for 41% of perforations, insertion and manipulations of the endoscope for 26%, guidewires for 15%, dilation of strictures for 3%, other instruments for 4%, stent insertion or migration for 2% and in 7% of cases the etiology was unknown.

| Ref. | Endo scope | ES | Guide wire | Dilation of strictures | Other instruments | Stent insertionor migration | Unknown |

| Alfieri et al[28], 2013 | 6 | 15 | 1 | 8 | |||

| Assalia et al[11], 2007 | 2 | 17 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Avgerinos et al[12], 2009 | 9 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Dubecz et al[13], 2012 | 7 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Enns et al[14], 2002 | 5 | 13 | 13 | 2 | |||

| Fatima et al[15], 2007 | 8 | 11 | 24 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 11 |

| Krishna et al[29], 2011 | 11 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Kayhan et al[17], 2004 | 2 | 15 | |||||

| Kim et al[18], 2011 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |||

| Kim et al[19], 2012 | 13 | 25 | 23 | 2 | 5 | ||

| Knudson et al[20], 2008 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 8 | ||

| Kwon et al[21], 2012 | 21 | 24 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Mao et al[23], 2008 | - | 8 | 1 | ||||

| Li et al[22], 2012 | 7 | 5 | 4 | ||||

| Morgan et al[25], 2009 | 12 | 12 | |||||

| Polydorou et al[26], 2011 | 7 | 30 | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Stapfer et al[8], 2000 | 5 | 6 | 3 | ||||

| Wu et al[27], 2006 | 5 | 11 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Total (%) | 130 (25) | 213 (41) | 84 (16) | 15 (3) | 25 (5) | 11 (2) | 42 (8) |

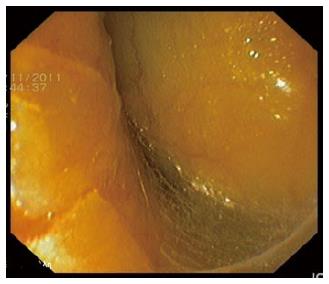

Early diagnosis and prompt treatment during the endoscopic procedure are vital for a better outcome[7,30]. ERCP-related perforations can usually been diagnosed during ERCP, from the endoscopic view or using fluoroscopy. In a review of 437 cases from 15 studies[8,12-15,17-24,26,27] the diagnosis was made during ERCP in 73% of cases (Table 3). The definition of delayed diagnosis was inconsistent between studies, but it was considered to be associated with worst prognosis[11,16,22]. Type I perforations can be diagnosed from direct visualization of the retroperitoneal space (Figure 1) or the abdominal cavity. In doubtful cases with bleeding and not clear endoscopic view, the use of fluoroscopy with or without contrast injection can confirm the diagnosis. Type II perforations can be suspected after a large or wrong direction sphincterotomy and can be confirmed by fluoroscopy. Fluoroscopy will reveal the presence of retroperitoneal air, especially around the right kidney with delineation of kidney margin (Figure 2) and occasionally the outlining of psoas muscle. The injection of contrast can also show leaking from the sphincterotomy site. Type III perforations can be diagnosed by the unusual passage of the guide wire or by the injection of contrast.

| Ref. | During ERCP (%) | After ERCP |

| Avgerinos et al[12], 2009 | 4 (26) | 11 |

| Dubecz et al[13], 2012 | 5 (45) | 6 |

| Enns et al[14], 2002 | 28 (84) | 5 |

| Fatima et al[15], 2007 | 45 (60) | 30 |

| Kayhan et al[17], 2004 | 17 (100) | 0 |

| Kim et al[18], 2011 | 10 (77) | 3 |

| Kim et al[19], 2012 | 46 (95) | 2 |

| Knudson et al[20], 2008 | 11 (34) | 21 |

| Kwon et al[21], 2012 | 39 (73) | 14 |

| Li et al[22], 2012 | 16 (100) | 0 |

| Mao et al[23], 2008 | 8 (88) | 1 |

| Miller et al[24], 2013 | 18 (66) | 9 |

| Polydorou et al[26], 2011 | 42 (95) | 2 |

| Stapfer et al[8], 2000 | 13 (93) | 1 |

| Wu et al[27], 2006 | 19 (63) | 11 |

| Total | 321(73) | 116 |

At the end of every endoscopic procedure, thorough control for any possible perforation should be performed. The endoscopist should inspect the circumference of the duodenum carefully and check the X-ray for the presence of retroperitoneal air. This concern is especially true when the procedure is technically difficult; needle-knife precut has been performed; there are variations in the usual anatomy due to previous operative interventions; strictures are dilated. If there is high suspicion contrast medium can be infused through the endoscope to facilitate identification of the injury.

Patients with undetected leaks can present hours after the ERCP with pain, fever and leukocytosis. In cases of intraperitoneal type I perforations, the diagnosis is usually obvious with severe pain and signs of peritonitis. When a patient experiences severe pain after ERCP, a differential diagnosis between acute pancreatitis and perforation should be made. In cases of retroperitoneal perforations the diagnosis is not so obvious. The patient may complain of mild epigastric pain but signs of peritonitis may develop after several hours or may not develop at all, depending on the size of the leak. The presence of subcutaneous emphysema may be evident from the first hours, especially at right abdominal wall, back or even cervix. Tachycardia is a constant finding, but it can be caused by other factors including pain. Leukocytosis and fever are often seen 12 h or more after completion of the procedure. A mild elevation of serum amylase levels is caused from the absorption of pancreatic fluid from the retroperitoneal space.

In cases with suspicion of perforation, a CT scan with oral contrast should be obtained. The presence of retroperitoneal air can also be detected by plain films, but CT scan is more sensitive[10,31], it may demonstrate the leak and the presence of fluid collections.

After the recognition of an ERCP-related perforation, the first dilemma is conservative treatment or surgery. That depends on the mechanism of injury, site and degree of leak and patient condition[28,32]. Endoscope related perforations (type I) should be referred for immediate surgery, unless endoscopic closure can be achieved. Endoscopic closure using fibrin glue, endoloops and endoclips or an over the scope clipping device has been described[33-36].

In cases of endoscopic sphincterotomy related perforations (type II), when diagnosed during the procedure, biliary drainage is essential in order to prevent leakage of bile into the perforation site. In Enns study[14], 5/13 patients with type II injuries were managed successfully either with plastic biliary stents or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. In Alfieri et al[28]’s study, 12/30 patients with early diagnosis were successfully treated conservatively with nasobiliary drainage.

Several case series have reported the use of fully covered self expandable metallic stents (SEMS) in sphincterotomy related perforations. SEMS have the advantage of covering the laceration and permit free flow of bile into the duodenum instead of into the retroperitoneal space. It seems better to use a covered SEMS because plastic stents or nasobiliary drains may not prevent bile flow into the perforation site completely. SEMS can also be used later with a repeat ERCP when the leak persists[37-40]. The advantages and disadvantages of different types of stents are shown in Table 4.

| Technical success | Biliary drainage | Covering the perforation | Repeat ERCP for removal | Cost | |

| SEMS | +++ | +++ | +++ | Y | +++ |

| Plastic biliary stents | +++ | ++ | + | Y | + |

| Nasobiliary drain | +++ | + | _ | N | + |

When a sphincterotomy related perforation is diagnosed after the procedure it should be assessed by a CT scan with contrast orally to demonstrate the degree of leak. Major contrast leak is an indication for immediate surgery, whilst minimal or no leak can be treated non-operatively[30,32]. Non-operative treatment includes nil by mouth, nasogastric tube, intravenous fluid resuscitation, broad spectrum antibiotics, repeat endoscopy for stenting in selected cases, and radiologic interventions for percutaneous drainage of fluid collections. Total parenteral nutrition is recommended in undernourished patients or when adequate enteral feeding will be impeded for at least seven days[41]. Generally, indications for surgery are: Major contrast leak; sepsis despite non-surgical treatment; presence of peritonitis or retroperitoneal fluid collections not amenable to percutaneous drainage; unsolved problems like stones or retained hardware (baskets)[28,30,32,41]. The clinical condition of the patient should be the key factor determining the mode of treatment[14,28,42]. Knudson et al[20] devised a clinical index score to predict the need for operative intervention. This 4-point scoring system assigned 1 point for each of the following: fever, tachycardia, guarding on examination and leukocytosis. The odds ratio for requiring operative management in patients with a score of greater than or equal to 3 was 40 (5.3-303.1, P < 0.001). In two studies[15,26] applying multivariate logistic regression analysis only ASA score and site of perforation remained significant for predicting operative treatment.

Reviewing 11 studies[8,11,14,18,21-27], after initial non-surgical treatment, surgery was required in 29/137 (21%) of patients with type II perforations, with an overall mortality of 9.4% (Table 5). The mortality of patients who required surgery was high (38%). Non-surgical management was successful in all patients with type III perforations (Table 4). In a recent review[32] conservative management was successful in 92.9% of patients with both types of injuries, treated initially non-operatively, with a final mortality of 0.6%.

| Ref. | Type II | Type III | |||||

| n | Surgery(%) | Mortality (%) | n | Surgery (%) | Mortality (%) | ||

| After surgery | Overall | ||||||

| Assalia et al[11], 2007 | 17 | 2 (11) | 1 (50) | 1 (6) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Enns et al[14], 2002 | 13 | 2 (15) | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Kim et al[18], 2011 | 3 | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Kwon et al[21], 2012 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Li et al[22], 2012 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mao et al[23], 2008 | 8 | 3 (37) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Miller et al[24], 2013 | 9 | 7 (77) | 5 (71) | 6 (66) | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Morgan et al[25], 2009 | 12 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Polydorou et al[26], 2011 | 30 | 6 (20) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Stapfer et al[8], 2000 | 5 | 3 (60) | 1 (33) | 1 (20) | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Wu et al[27], 2006 | 11 | 5 (45) | 4 (80) | 4 (36) | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 137 | 29 (21) | 11 (38) | 13 (9.4) | 53 | 0 | 0 |

In the available literature there are no prospective comparative studies between surgical techniques for ERCP-related perforations. Surgical technique depends on site and size of defect, timing of surgery and clinical condition of the patient.

The main goal of immediate surgery is to repair the perforation and diversion of bile and gastric fluid, if required. Endoscope related duodenal perforations (type I) can be closed primarily in one or two layers, following debridement of devitalized tissue. The closure should be oriented transversely in order to avoid compromising the duodenal lumen. In cases with large defects the options are jejunal serosal patch closure or tube duodenostomy. Leak from the duodenal closure line is a major concern and duodenal diversion should be suggested in large defects or delayed diagnosis. The rationale is to divert the gastrointestinal content and proteolytic enzymes from the duodenal repair site. In sphincterotomy related perforations (type II), a non-operative approach is successful in nearly 80% of cases. When the clinical condition of the patient or the size of the leak requires immediate surgery, a transduodenal approach and repair, by performing sphincteroplasty within 24 h, has been described with good results[43].

The main goals of delayed surgery are to control sepsis, to repair the perforation if possible, and diversion, if required[28,30,32,43,44]. Delayed surgery is performed in patients who remain septic despite non-operative treatment, and debridement and drainage of the retroperitoneal space is required. That can be achieved by an extraperitoneal approach (right posterior laparostomy)[28] or transperitoneal approach when cholecystectomy, common bile duct exploration with T-tube placement or diversion techniques are required. The perforation site cannot be found in 16% to 80% in delayed surgery[24,27,44] or the tissues are too edematous for primary repair. The transduodenal approach is not indicated for delayed surgery.

Diversion of gastric and duodenal fluid is mandatory and can be achieved by: placement of a nasogastric or nasoduodenal tube; tube duodenostomy; pyloric exclusion and gastrojejunostomy; gastrojejunostomy alone; T-tube placement for bile diversion; duodenal diverticulization[7,8,11,12,15,20,23,25,27,29]. Duodenal diverticulization consists of Billroth II gastrectomy, placement of a decompressive catheter into the duodenum, closure of duodenal wound and drainage[45]. The main drawback of duodenal diverticulization is that it is an extensive procedure which may be inappropriate in septic, unstable patients. Pyloric exclusion is a less invasive alternative. This procedure consists of duodenal wound repair, closure of the pylorus with a running suture or by stapling and gastrojejunostomy. Pyloric exclusion is a less extensive procedure, less time consuming, causes less physiological disturbances and it is advocated by most clinicians, when duodenal diversion is required.

In conclusion, ERCP-related perforation is uncommon (0.39%), but it is associated with an overall mortality of 7.8%. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential for a better outcome. The mechanism, site and extent of injury, suggested by clinical and radiographic findings, should guide towards conservative or surgical management. In type I perforations early surgical repair is indicated, unless endoscopic closure can be achieved. Patients with type II perforations should be treated initially non-operatively. Non-operative treatment is successful in 79% of patients with an overall mortality of 9.4%. Non-operative treatment is sufficient in all patients with type III injuries. Surgical technique depends on size and site of defect, timing and clinical condition of the patient.

P- Reviewer: Chen CH, Changela K, Tantau A S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:721-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1690] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A, Dinelli M, Minoli G, Crosta C, Comin U, Fertitta A. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F, De Berardinis F, De Bernardin M, Ederle A, Fina P, Fratton A. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Williams EJ, Taylor S, Fairclough P, Hamlyn A, Logan RF, Martin D, Riley SA, Veitch P, Wilkinson ML, Williamson PR. Risk factors for complication following ERCP; results of a large-scale, prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:793-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G, Niro G, Valvano MR, Spirito F, Pilotto A, Forlano R. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: a systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1781-1788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 669] [Cited by in RCA: 772] [Article Influence: 42.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Howard TJ, Tan T, Lehman GA, Sherman S, Madura JA, Fogel E, Swack ML, Kopecky KK. Classification and management of perforations complicating endoscopic sphincterotomy. Surgery. 1999;126:658-663; discussion 664-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stapfer M, Selby RR, Stain SC, Katkhouda N, Parekh D, Jabbour N, Garry D. Management of duodenal perforation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. Ann Surg. 2000;232:191-198. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Genzlinger JL, McPhee MS, Fisher JK, Jacob KM, Helzberg JH. Significance of retroperitoneal air after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1267-1270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | de Vries JH, Duijm LE, Dekker W, Guit GL, Ferwerda J, Scholten ET. CT before and after ERCP: detection of pancreatic pseudotumor, asymptomatic retroperitoneal perforation, and duodenal diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:231-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Assalia A, Suissa A, Ilivitzki A, Mahajna A, Yassin K, Hashmonai M, Krausz MM. Validity of clinical criteria in the management of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography related duodenal perforations. Arch Surg. 2007;142:1059-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Avgerinos DV, Llaguna OH, Lo AY, Voli J, Leitman IM. Management of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: related duodenal perforations. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:833-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dubecz A, Ottmann J, Schweigert M, Stadlhuber RJ, Feith M, Wiessner V, Muschweck H, Stein HJ. Management of ERCP-related small bowel perforations: the pivotal role of physical investigation. Can J Surg. 2012;55:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Enns R, Eloubeidi MA, Mergener K, Jowell PS, Branch MS, Pappas TM, Baillie J. ERCP-related perforations: risk factors and management. Endoscopy. 2002;34:293-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fatima J, Baron TH, Topazian MD, Houghton SG, Iqbal CW, Ott BJ, Farley DR, Farnell MB, Sarr MG. Pancreaticobiliary and duodenal perforations after periampullary endoscopic procedures: diagnosis and management. Arch Surg. 2007;142:448-54; discussion 454-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jin YJ, Jeong S, Kim JH, Hwang JC, Yoo BM, Moon JH, Park SH, Kim HG, Lee DK, Jeon YS. Clinical course and proposed treatment strategy for ERCP-related duodenal perforation: a multicenter analysis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:806-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kayhan B, Akdoğan M, Sahin B. ERCP subsequent to retroperitoneal perforation caused by endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:833-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim BS, Kim IG, Ryu BY, Kim JH, Yoo KS, Baik GH, Kim JB, Jeon JY. Management of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related perforations. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81:195-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim J, Lee SH, Paik WH, Song BJ, Hwang JH, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yoon YB. Clinical outcomes of patients who experienced perforation associated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3293-3300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Knudson K, Raeburn CD, McIntyre RC, Shah RJ, Chen YK, Brown WR, Stiegmann G. Management of duodenal and pancreaticobiliary perforations associated with periampullary endoscopic procedures. Am J Surg. 2008;196:975-81; discussion 981-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kwon W, Jang JY, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yoon YB, Kang MJ, Kim SW. Proposal of an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related perforation management guideline based on perforation type. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;83:218-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li G, Chen Y, Zhou X, Lv N. Early management experience of perforation after ERCP. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:657418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mao Z, Zhu Q, Wu W, Wang M, Li J, Lu A, Sun Y, Zheng M. Duodenal perforations after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: experience and management. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:691-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Miller R, Zbar A, Klein Y, Buyeviz V, Melzer E, Mosenkis BN, Mavor E. Perforations following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a single institution experience and surgical recommendations. Am J Surg. 2013;206:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Morgan KA, Fontenot BB, Ruddy JM, Mickey S, Adams DB. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography gut perforations: when to wait! When to operate! Am Surg. 2009;75:477-483; discussion 483-484. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Polydorou A, Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Katsarelias D, Vagianos C, Polymeneas G. A tailored approach to the management of perforations following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2211-2217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wu HM, Dixon E, May GR, Sutherland FR. Management of perforation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): a population-based review. HPB (Oxford). 2006;8:393-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Alfieri S, Rosa F, Cina C, Tortorelli AP, Tringali A, Perri V, Bellantone C, Costamagna G, Doglietto GB. Management of duodeno-pancreato-biliary perforations after ERCP: outcomes from an Italian tertiary referral center. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2005-2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Krishna RP, Singh RK, Behari A, Kumar A, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography perforation managed by surgery or percutaneous drainage. Surg Today. 2011;41:660-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Preetha M, Chung YF, Chan WH, Ong HS, Chow PK, Wong WK, Ooi LL, Soo KC. Surgical management of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related perforations. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:1011-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kuhlman JE, Fishman EK, Milligan FD, Siegelman SS. Complications of endoscopic retrograde sphincterotomy: computed tomographic evaluation. Gastrointest Radiol. 1989;14:127-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Machado NO. Management of duodenal perforation post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. When and whom to operate and what factors determine the outcome? A review article. JOP. 2012;13:18-25. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Mutignani M, Iacopini F, Dokas S, Larghi A, Familiari P, Tringali A, Costamagna G. Successful endoscopic closure of a lateral duodenal perforation at ERCP with fibrin glue. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:725-727. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Nakagawa Y, Nagai T, Soma W, Okawara H, Nakashima H, Tasaki T, Hisamatu A, Hashinaga M, Murakami K, Fujioka T. Endoscopic closure of a large ERCP-related lateral duodenal perforation by using endoloops and endoclips. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:216-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Buffoli F, Grassia R, Iiritano E, Bianchi G, Dizioli P, Staiano T. Endoscopic “retroperitoneal fatpexy” of a large ERCP-related jejunal perforation by using a new over-the-scope clip device in Billroth II anatomy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1115-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Doğan ÜB, Keskın MB, Söker G, Akın MS, Yalaki S. Endoscopic closure of an endoscope-related duodenal perforation using the over-the-scope clip. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2013;24:436-440. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Jeon HJ, Han JH, Park S, Youn S, Chae H, Yoon S. Endoscopic sphincterotomy-related perforation in the common bile duct successfully treated by placement of a covered metal stent. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E295-E296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Park WY, Cho KB, Kim ES, Park KS. A case of ampullary perforation treated with a temporally covered metal stent. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:177-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Nastos C, Yiallourou A, Polydorou A, Voros D. Closure of a persistent sphincterotomy-related duodenal perforation by placement of a covered self-expandable metallic biliary stent. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4539-4541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lee SM, Cho KB. Value of temporary stents for the management of perivaterian perforation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:689-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Paspatis GA, Dumonceau JM, Barthet M, Meisner S, Repici A, Saunders BP, Vezakis A, Gonzalez JM, Turino SY, Tsiamoulos ZP. Diagnosis and management of iatrogenic endoscopic perforations: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy. 2014;46:693-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Chung RS, Sivak MV, Ferguson DR. Surgical decisions in the management of duodenal perforation complicating endoscopic sphincterotomy. Am J Surg. 1993;165:700-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Sarli L, Porrini C, Costi R, Regina G, Violi V, Ferro M, Roncoroni L. Operative treatment of periampullary retroperitoneal perforation complicating endoscopic sphincterotomy. Surgery. 2007;142:26-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ercan M, Bostanci EB, Dalgic T, Karaman K, Ozogul YB, Ozer I, Ulas M, Parlak E, Akoglu M. Surgical outcome of patients with perforation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Berne CJ, Donovan AJ, White EJ, Yellin AE. Duodenal “diverticulization” for duodenal and pancreatic injury. Am J Surg. 1974;127:503-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |