Published online Sep 10, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i12.1070

Peer-review started: April 12, 2015

First decision: June 4, 2015

Revised: July 22, 2015

Accepted: August 13, 2015

Article in press: August 26, 2015

Published online: September 10, 2015

Processing time: 153 Days and 20.5 Hours

AIM: To examine the efficacy of non-magnifying narrow-band imaging (NM-NBI) imaging for small signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC).

METHODS: We retrospectively analyzed 14 consecutive small intramucosal SRCs that had been treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and 14 randomly selected whitish gastric ulcer scars (control). The strength and shape of the SRCs and whitish scars by NM-NBI and white-light imaging (WLI) were assessed with Image J (NIH, Bethesda).

RESULTS: NM-NBI findings of SRC showed a clearly isolated whitish area amid the brown color of the surrounding normal mucosa. The NBI index, which indicates the potency of NBI for visualizing SRC, was significantly higher than the WLI index (P = 0.001), indicating SRC was more clearly identified by NM-NBI. Although the NBI index was not significantly different between SRCs and controls, the circle (C)-index, as an index of circularity of tumor shape, was significantly higher in SRCs (P = 0.001). According to the receiver-operating characteristic analysis, the resulting cut-off value of the circularity index (C-index) for SRC was 0.60 (85.7% sensitivity, 85.7% specificity). Thus a lesion with a C-index ≥ 0.6 was significantly more likely to be an SRC than a gastric ulcer scar (OR = 36.0; 95%CI: 4.33-299.09; P = 0.0009).

CONCLUSION: Small isolated whitish round area by NM-NBI endoscopy is a useful finding of SRCs which is the indication for ESD.

Core tip: Intramucosal signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC) ≤ 2 cm in diameter, for which endoscopic submucosal dissection is indicated, is very difficult to identify by white-light imaging (WLI) endoscopy. However, little is known regarding non-magnifying narrow-band imaging (NM-NBI) findings of early SRC. The strength and shape of the SRCs by NM-NBI and WLI were assessed with Image J. NM-NBI findings of SRC showed a clearly isolated whitish area amid the brown color of the surrounding normal mucosa. The NBI index, which indicates the potency of NBI for visualizing SRC, was significantly higher than the WLI index (P = 0.001).

- Citation: Watari J, Tomita T, Ikehara H, Taki M, Ogawa T, Yamasaki T, Kondo T, Toyoshima F, Sakurai J, Kono T, Tozawa K, Ohda Y, Oshima T, Fukui H, Hirota S, Miwa H. Diagnosis of small intramucosal signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach by non-magnifying narrow-band imaging: A pilot study. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(12): 1070-1077

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i12/1070.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i12.1070

Gastric cancer ranks as the fourth most common cancer and the second most frequent cause of death from cancer in the world[1]. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is considered to be a main risk factor for the development of gastric cancer of either intestinal or diffuse type[2]. However, according to recent reports, the H. pylori infection rate has decreased over the last 40-50 years in both Asia and Western countries, with an overall decline in H. pylori seroprevalence[3,4]. In Japan, the prevalence of H. pylori-negative gastric cancer is extremely low; therefore, the prevalence of gastric cancer may continue to decrease substantially as the H. pylori infection rate continues to decrease[5,6]. The pathological characteristics of H. pylori-negative gastric cancer are different from those of H. pylori-positive gastric cancer; histologically, the diffuse type is dominant, especially signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC) (60%)[6]. Commonly, SRC of the stomach is thought to arise in the mucosa without metaplastic change and is typically confined to the glandular neck region in the original proliferation zone[7]. It is considered, therefore, that early-stage SRCs can be present beneath a flat, intact mucosal surface epithelium, and may be very difficult to identify by white-light imaging (WLI) endoscopy due to their slightly whitish discoloration.

Recently, magnifying narrow-band imaging (NBI) has been reported to be useful for the accurate diagnosis of gastric cancers, even for small, depressed gastric mucosal cancers[8-11]. Several studies have demonstrated an association between the histology, i.e., differentiated vs undifferentiated type, and magnified NBI appearance[8,11-13]. In cases of SRC, the cancer-specific findings and identifiable demarcation line of the lesion may not be identified even by magnifying NBI endoscopy or chromoendoscopy[12,13]. We have found intramucosal SRCs by non-magnifying NBI (NM-NBI) endoscopy that we failed to detect by WLI endoscopy. Nonetheless, there has been little research into NM-NBI findings focused strictly on intramucosal SRCs.

It has been reported that patients with SRC caught at an early stage can expect a better prognosis than they might with other gastric cancers[14] and SRC is not a prognostic factor in early cancer[15]. The prognosis of those at the advanced stage is still controversial; a report by Otsuji et al[14] from Japan showed no significant difference in 5-year survival rates between patients with SRC and those with other histological types of gastric cancer, while other studies from the West[16-18] have found that SRC has a worse prognosis due to specific characteristics such as high rate of lymph node metastasis and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Clearly, it is best to discover gastric SRC early, but the early detection of lesions located beneath a preserved surface epithelium may be very difficult.

Although NBI is increasingly available in endoscopy units, only a limited number of cases are subjected to magnifying NBI endoscopy, even in hospitals specializing in gastroenterology. Many gastroenterologists or endoscopists use a conventional NM-NBI endoscope lacking a magnification function to screen for gastric cancer. In the present study, we (1) retrospectively investigated endoscopic findings of SRC by NM-NBI endoscopy and WLI endoscopy; and (2) compared the NBI findings of SRC and whitish gastric ulcer scars, in order to clarify the NM-NBI features of SRC.

Between January 2011 and May 2014 in our department, 322 early gastric cancers or adenomas in 301 patients were treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). The indications for ESD of intramucosal gastric cancer or adenoma, included the following[19]: (1) intramucosal differentiated-type adenocarcinoma of any size without ulceration; (2) intramucosal differentiated-type adenocarcinoma with an ulcer scar and measuring ≤ 3 cm in diameter; and (3) intramucosal undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma, including poorly differentiated cancer or SRC, of less than 2 cm without an ulcer scar. In all cases, the histology, tumor location, macroscopic classification, and depth of invasion fulfilled the criteria of the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer[20]. Among these cases treated with ESD, 14 (4.3%) were diagnosed histologically as intramucosal SRC (≤ 2 cm) without any other findings of adenocarcinoma. During the same period, 14 patients with whitish gastric ulcer scars that were histologically confirmed by biopsy were randomly selected as controls.

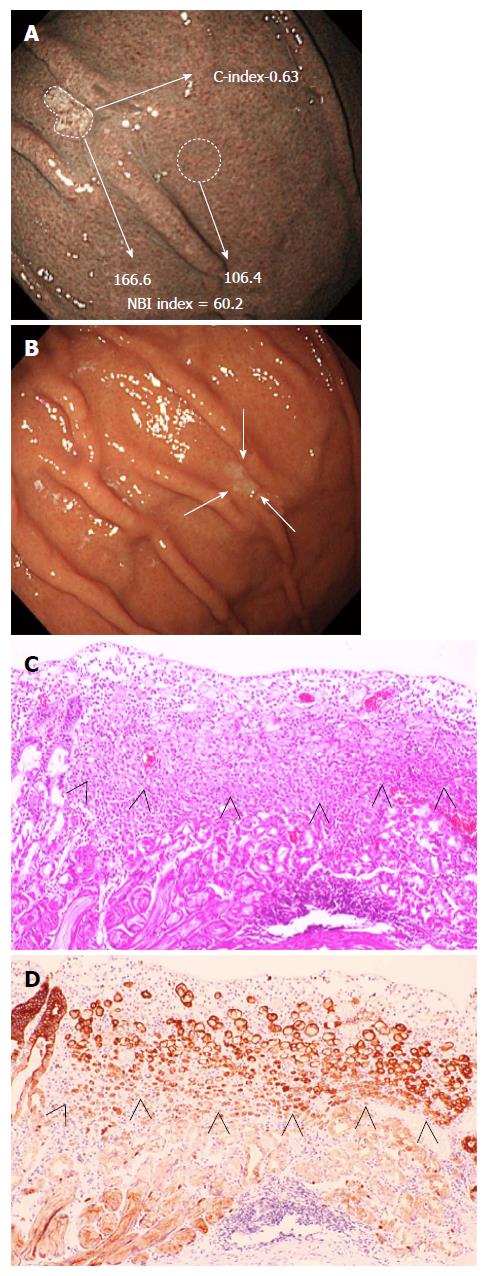

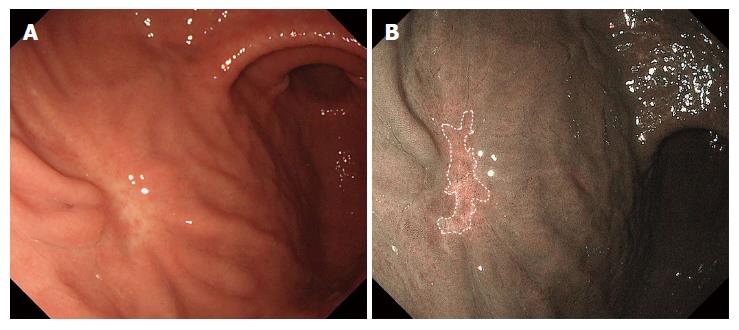

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients who underwent a routine endoscopic examination and ESD, and this study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients underwent NM-NBI endoscopy by an endoscope (GIF-Q260) or high-vision endoscope (H260, H260Z, H290 and HQ290) with an electronic endoscopic system (Evis Lucera CV-260 SL or Elite CV-290; Olympus Medical Systems, Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The strengths of the NM-NBI and WLI images of 14 consecutive gastric SRCs undergoing ESD and the strength of the NM-NBI images of gastric ulcer scars (controls) were quantified with an image-analytical software program. Briefly, NBI images were converted into joint photographic experts group pictures; then the cancer or ulcer scar area on the pictures was manually traced with an image-analytical software program (ImageJ ver. 1.48; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Using the default tool “Measure” under the “Analyze” menu, the mean gray value (MGV) of the cancer or ulcer area was calculated, and the MGV of a region of similar area of the perilesional normal mucosa was also measured. The MGV of the cancer or ulcer scar area minus that of the perilesional area was defined as the NBI index (Figure 1; note, a brighter image has a higher MGV). In addition, the values for several shape descriptors of the SRCs and gastric ulcer scars were also calculated to assess their shapes. Briefly, using the default tool “Measure” under the “Analyze” menu, “Circ.” was adopted as the circularity index (C-index). The C-index value of a perfect circle is 1; as the shape deviates from perfectly circular, the C-index value decreases (Figure 2). The WLI strength was calculated as well as the NM-NBI index, and was measured by “RGB Measure (R + G + B/3)” tool under the “Analyze” menu in “Plugins”. The quantification was performed by an endoscopist who was not involved in the patients’ original diagnoses or treatments.

To assess H. pylori infection, biopsy specimens, two from each site, were taken from the greater curvature of the antrum and body of the stomach. H. pylori status was analyzed in each patient by two methods: Giemsa staining and serum H. pylori-IgG antibody with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit using the E plate test (Eiken Kagaku, Tokyo, Japan). A patient was regarded as positive for H. pylori if at least one of these tests was positive.

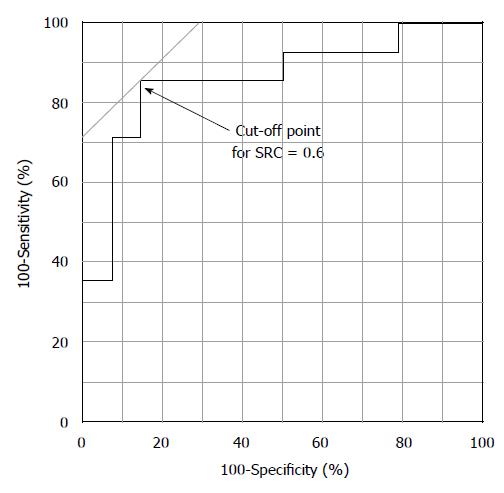

The data were assessed by the Mann-Whitney U-test for comparisons between two independent groups and the Fisher’s exact test for comparisons between two proportions. NM-NBI findings including the NBI-index and C-index were included as potential malignant features for SRC in univariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify significant predictive NBI findings. Odds ratios and 95%CIs were used to assess the statistical significance at the conventional level of 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with StatView version 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated for the highest diagnostic performance in terms of the shape of SRCs (C-index), and then the curve was plotted using JMP 10 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The area under the ROC curve and the optimal thresholds using the Youden index were calculated from ROC analysis[21].

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 14 SRCs in the 13 patients who underwent ESD and the controls. In addition, clinical and endoscopic data of SRCs are shown in Table 2. Out of 14 SRCs, 10 lesions were detected at other hospitals and then referred to our department for ESD treatment. Two (cases 4 and 12) of the 14 SRCs were first identified by NM-NBI endoscopy, but not by WLI endoscopy, in our department (Figure 1). In SRC patients, the mean age was 53.2 ± 14.2 years (range: 23 to 74 years), and women accounted for 46.2% (6 of 13) of the group. In contrast, the mean age of the controls was 69.1 ± 14.8 years, significantly higher than that of the SRC patients. The H. pylori-negative rate was 69.2% (9 of 13) in the SRC patients, and none of these patients had received H. pylori eradication therapy. In the control group, 4 out of 5 H. pylori-negative patients (35.7%, 5 of 14) had undergone eradication therapy previously.

| SRC | Control | P value | |

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 53.2 ± 14.2 | 69.1 ± 14.8 | 0.0008 |

| Sex, male/female | 7/6 | 10/4 | 0.44 |

| Location: upper/middle/lower | 2/7/5 | 4/8/2 | 0.36 |

| NBI finding | |||

| NBI index (mean ± SD) | 27.9 ± 21.0a | 24.8 ± 14.7 | 0.78 |

| H. pylori: positive/negative | 26.1 ± 20.5/29.0 ± 22.4 | 27.8 ± 15.4/19.3 ± 13.2 | 0.95 in SRC and 0.26 in control |

| WLI finding (mean ± SD) | |||

| WLI index | 5.3 ± 16.2a | - | 0.001a |

| H. pylori: positive/negative | 13.5 ± 16.4/0.7 ± 15.1 | - | 0.32 |

| C-index (mean ± SD) | 0.67 ± 0.13 | 0.50 ± 0.14 | 0.001 |

| Case | Age | Sex | Type | Size (mm) | Location | Location | Hp | PDE | NBI index | WLI index | C-index | Endoscopic system |

| 1 | 23 | Female | IIb | 4 | M | GC | + | - | 22.5 | 3.5 | 0.75 | CV-260 SL |

| IIc | 6 | L | GC | - | 25.6 | 16.1 | 0.67 | CV-290 | ||||

| 2 | 63 | Female | IIb | 14 | M | LC | + | + | 5.5 | 2.2 | 0.76 | CV-260 SL |

| 3 | 62 | Male | IIc | 15 | M | GC | + | - | 16.8 | 41.1 | 0.61 | CV-260 SL |

| 4 | 74 | Female | IIc | 4 | U | GC | + | + | 60.2 | 4.5 | 0.63 | CV-260 SL |

| 5 | 48 | Male | IIc | 4 | L | GC | - | - | 59.6 | 0.22 | 0.66 | CV-260 SL |

| 6 | 62 | Male | IIb | 5 | M | LC | - | + | 17.6 | -2.7 | 0.81 | CV-260 SL |

| 7 | 48 | Male | IIc | 2 | U | GC | - | - | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.33 | CV-260 SL |

| 8 | 58 | Male | IIc | 5 | L | LC | - | - | 19.5 | -33.7 | 0.88 | CV-260 SL |

| 9 | 40 | Female | IIb | 6 | M | GC | - | - | 25.6 | 12.8 | 0.77 | CV-290 |

| 10 | 69 | Female | IIb | 8 | L | PW | - | - | 68.5 | -8.5 | 0.60 | CV-290 |

| 11 | 46 | Male | IIb | 5 | M | GC | - | - | 10.8 | 9.3 | 0.63 | CV-290 |

| 12 | 60 | Male | IIb | 6 | M | GC | - | - | 19.7 | 16.3 | 0.57 | CV-290 |

| 13 | 38 | Female | IIb | 6 | L | PW | - | - | 38.2 | 8.7 | 0.69 | CV-290 |

Most SRCs were located in the middle or lower portion of the stomach (85.7%, 12 of 14) and at the greater curvature (64.3%, 9 of 14), with no significant difference in the distribution of lesions compared to the control. The average diameter of the major axis of the SRCs was 6.4 mm (range: 2 to 15 mm). Histologically, a partial defect of the foveolar epithelium was identified in only 3 cases (21.4%); thus, most SRC cells were found beneath a preserved surface epithelium. In all SRC cases, the histological growth pattern of cancer cells corresponded to the non-whole-layer type according to the definition by Okada et al[13].

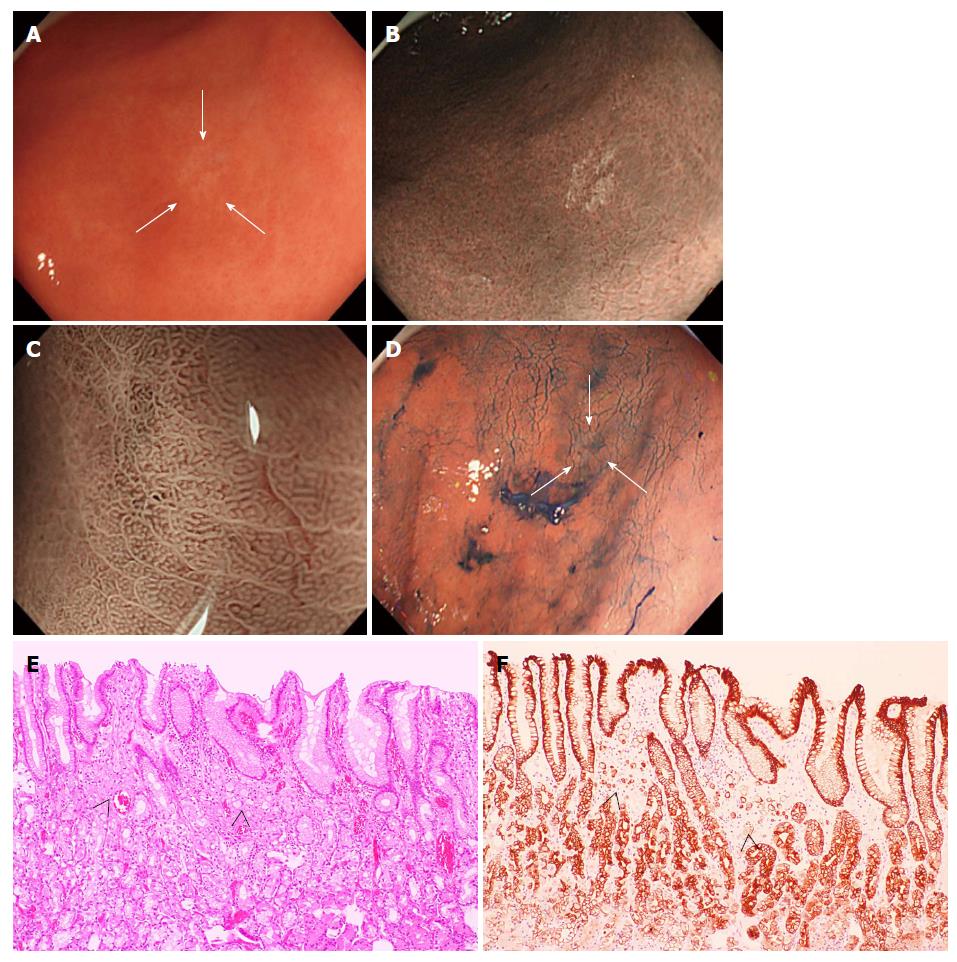

In SRCs, NBI findings showed a clearly isolated whitish area amid the brown color of the normal mucosa. The NBI index (27.9 ± 21.0) was significantly higher than the WLI index (5.3 ± 16.2) (P = 0.001), indicating that the contrast between the cancer and surrounding normal mucosa was more intense by NM-NBI than by WLI. This result indicates that the cancerous areas were more clearly captured by NM-NBI endoscopy than by WLI endoscopy (Figures 1 and 3). The overall mean NBI index was 27.9 ± 21.0; this value was not significantly different from that (24.8 ± 14.7) of the control. Moreover, the NBI indices were not significantly different between the H. pylori-positive and -negative cases in either the SRCs or controls. In addition, the WLI index of the SRCs was not significantly different between H. pylori-positive and -negative cases. In contrast, the C-index was significantly higher in SRCs (0.67 ± 0.13) than in controls (0.50 ± 0.14) (P = 0.001), indicating that SRCs are rounder in shape than ulcer scars (Table 1). The C-index was the only factor significantly associated with SRCs in the NBI findings.

The association between the shape of SRCs and C-index was evaluated using ROC curve analysis (Figure 4). According to this analysis, the resulting cut-off value of the C-index for SRC was 0.60 (sensitivity, 85.7%; specificity, 85.7%).

Based on the ROC curve analysis and optimal cut-off points of the C-index of SRC determined above, a C-index of ≥ 0.60 was used in the analysis. We investigated the strength of the association between the C-index (≥ 0.60) in the NM-NBI findings and that in the SRCs by means of a logistic regression analysis. The C-index (≥ 0.60) was found to be a significant predictor of SRCs (OR = 36.0; 95%CI: 4.33-299.09; P = 0.0009).

As the H. pylori infection rate continues to decrease, cardiac or junctional gastric cancer and histologically undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma including SRC will increase in proportion. Therefore, there is need of an easy method for detecting these cancers in an early stage by routine endoscopy. Magnifying NBI is definitely useful for the accurate diagnosis of gastric cancer or dysplasia using the criteria for gastric cancer: irregularity or disappearance of the mucosal structure or a microvascular pattern in a definite demarcation line[8-13]. However, small intramucosal SRCs (≤ 2 cm), which are best treated by ESD, have fewer of these magnifying NBI findings, because most intramucosal SRC cells are covered by a normal foveolar epithelium. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report on the NM-NBI findings and clinical features of small SRC, for which endoscopic treatment is indicated.

In a previous magnifying NBI study of undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer including SRCs[8,11-13], Okada et al[13] found that gastric cancers with a preserved but irregular surface pattern corresponded histologically to the non-whole-layer type of mucosal cancer, whereas cancers with an irregular microvascular pattern or mixed pattern upon magnifying NBI corresponded histopathologically to the whole-layer type of intramucosal cancer or submucosal invasion cancer[13]. In cases of small undifferentiated-type cancer in which cells infiltrate laterally in the lamina propria deep into the glandular neck, i.e., the non-whole-layer type, magnifying NBI cannot detect any cancer-specific irregular microvascular or microsurface pattern[9]. Therefore, it is difficult to detect undifferentiated-type cancer developing laterally within the proliferative zone and to identify the demarcation line of the cancer even by magnifying NBI, as shown in Figure 3[13]. Moreover, the extent of the lateral margin in this type of cancer becomes less detectable by chromoendoscopy (Figure 3)[12].

In the current study, however, SRCs were captured more easily by NM-NBI without the use of a magnifying endoscope than by WLI endoscopy; on NM-NBI they appeared as isolated whitish round areas. It remains unclear why the cancerous area of the SRC is whitish when compared to the surrounding normal mucosa. One possibility is that the depth of the crypt is shallow and the surface of the mucosa is planarized because of closely aggregated SRC cells in the upper to middle third of the mucosa (Figures 1 and 3). Okada et al[13] similarly presumed that both the number and heights of the gastric pits were decreased due to the extension of cancer cells in the mucosa, which eventually obliterated the architecture of the microsurface. As H. pylori infection causes extensive infiltration of inflammatory cells into the gastric mucosa, one would think this inflammation might affect the NBI index. However, no significant difference in the NBI index was seen between patients with and without H. pylori infection in either SRCs or controls. There was also no significant difference in the NBI index between the SRC and control groups themselves, while the C-index results indicated that the SRCs were significantly rounder than the gastric ulcer scars of the controls. Since the 1980s, irregular shape lesion has been known to reflect malignant finding in the diagnosis of small gastric cancers, especially those of differentiated-type[22], and thus the NM-NBI shape of small SRC might be different from that of differentiated-type cancer. In the present work, a C-index exceeding 0.60 was considered to be the most reliable factor associated with SRCs. In logistic regression analysis, as well, the C-index (≥ 0.60) was a highly significant predictor for SRC (OR = 36.0; 95%CI: 4.33-299.09; P = 0.0009). These results may suggest that NM-NBI could easily discriminate SRCs from gastric ulcer scars. However, gastric ulcer scars are histologically associated with complicated fibrosis in the submucosal layer, and thus it may not be surprising that their shape tended to be more irregular than that of SRCs.

More recently, novel electronic endoscopic systems (Evis Lucera Elite CV-290 and LASEREO, FUJIFILM Medical Co., Ltd., Tokyo) have been newly developed. These systems enable clearer and brighter NBI observation throughout the entire stomach than the existing systems (Evis Lucera CV-260 SL and Advancia, FUJIFILM Medical Co., Ltd., Tokyo). Therefore, it may be possible to identify small SRCs even from a relative distance by using a novel electronic endoscopic system. SRCs may be a form of incipient gastric cancer that may eventually develop into a linitis plastica-type cancer; hence, it is important to detect SRCs at an early stage. Our findings suggest the need to look carefully for isolated whitish round areas on NBI endoscopy, particularly in the greater curvature of the middle to lower portion of the stomach.

Nevertheless, the present study had some potential limitations. First, this was a retrospective study from a single institution with a small number of SRC cases. It will be important to perform a prospective study using the NBI criteria in order to confirm the reliability of these findings. However, the incidence of intramucosal SRC is low (4.3%) among the cases treated with ESD. Therefore, the incidence will be even lower in patients who undergo endoscopy for screening, indicating that a larger series of samples and an appreciable length of time will be required to assess the reliability. Second, ten of the SRC cases were referred to our department after biopsies at other clinics or hospitals; most lesions were biopsied prior to imaging. Thus, previous biopsy sites were covered by regenerated epithelium and might have influenced the NM-NBI findings[13]. However, the NBI index was not significantly different between biopsied and non-biopsied cases (data not shown).

In conclusion, it is best to look carefully for isolated whitish round areas by NM-NBI endoscopy for early detection of this malignancy. Here, we would like to emphasize that during an era when the incidence of H. pylori infection is decreasing, NM-NBI endoscopy should be used for the detection of small intramucosal SRCs.

As the authors described, the pathological characteristics of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-negative gastric cancer are different from those of H. pylori-positive gastric cancer; histologically, the diffuse type is dominant, especially signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC). Since early-stage SRC develops beneath a flat, intact mucosal surface epithelium, it is very difficult to identify by white-light imaging (WLI) endoscopy.

Magnifying narrow-band imaging (NBI) has been reported to be useful for the accurate diagnosis even in small gastric mucosal cancers. In cases of SRC, however, the cancer-specific findings and identifiable demarcation line of the lesion may not be identified even by magnifying NBI endoscopy or chromoendoscopy. To date, little is known regarding non-magnifying (NM)-NBI findings of small intramucosal SRC.

Intramucosal SRC could be clearly captured by NM-NBI as an isolated whitish area amid the brown color of the surrounding normal mucosa. SRCs were more clearly captured by NM-NBI endoscopy than by WLI endoscopy. Furthermore, although the NBI strengths of SRCs and whitish gastric ulcer scars were not significantly different, the two types of lesions’ indexes of circularity determined by image-analytical software were significantly different, with the SRCs being distinctly rounder in shape than the ulcer scars.

This study emphasizes that during an era when the incidence of H. pylori infection is decreasing, NM-NBI endoscopy should be used for the detection of small intramucosal SRCs, which is indicated for endoscopic submucosal dissection. It is best to look carefully for isolated whitish round areas by NM-NBI endoscopy for early detection of this malignancy.

NBI: Magnifying endoscopy with NBI is widely used in gastroscopy, especially in the diagnosis of early gastric cancer. SRC: Signet ring cell carcinoma is thought to arise in the mucosa without metaplastic change and is typically confined to the glandular neck region in the original proliferation zone; therefore, it is difficult to detect those lesions.

The manuscript is excellent with perfect language.

P- Reviewer: El Hak NG, Vieth M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893-2917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11128] [Cited by in RCA: 11836] [Article Influence: 845.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Fock KM, Ang TL. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:479-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Rahman R, Asombang AW, Ibdah JA. Characteristics of gastric cancer in Asia. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4483-4490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kato S, Matsukura N, Tsukada K, Matsuda N, Mizoshita T, Tsukamoto T, Tatematsu M, Sugisaki Y, Naito Z, Tajiri T. Helicobacter pylori infection-negative gastric cancer in Japanese hospital patients: incidence and pathological characteristics. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:790-794. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Matsuo T, Ito M, Takata S, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric cancer among Japanese. Helicobacter. 2011;16:415-419. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sugihara H, Hattori T, Fukuda M, Fujita S. Cell proliferation and differentiation in intramucosal and advanced signet ring cell carcinomas of the human stomach. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1987;411:117-127. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Nakayoshi T, Tajiri H, Matsuda K, Kaise M, Ikegami M, Sasaki H. Magnifying endoscopy combined with narrow band imaging system for early gastric cancer: correlation of vascular pattern with histopathology (including video). Endoscopy. 2004;36:1080-1084. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Yao K, Anagnostopoulos GK, Ragunath K. Magnifying endoscopy for diagnosing and delineating early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2009;41:462-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ezoe Y, Muto M, Uedo N, Doyama H, Yao K, Oda I, Kaneko K, Kawahara Y, Yokoi C, Sugiura Y. Magnifying narrowband imaging is more accurate than conventional white-light imaging in diagnosis of gastric mucosal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2017-2025.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li HY, Dai J, Xue HB, Zhao YJ, Chen XY, Gao YJ, Song Y, Ge ZZ, Li XB. Application of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging in diagnosing gastric lesions: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1124-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nagahama T, Yao K, Maki S, Yasaka M, Takaki Y, Matsui T, Tanabe H, Iwashita A, Ota A. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging for determining the horizontal extent of early gastric cancer when there is an unclear margin by chromoendoscopy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1259-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Okada K, Fujisaki J, Kasuga A, Omae M, Hirasawa T, Ishiyama A, Inamori M, Chino A, Yamamoto Y, Tsuchida T. Diagnosis of undifferentiated type early gastric cancers by magnification endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1262-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Otsuji E, Yamaguchi T, Sawai K, Takahashi T. Characterization of signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. J Surg Oncol. 1998;67:216-220. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Gronnier C, Messager M, Robb WB, Thiebot T, Louis D, Luc G, Piessen G, Mariette C. Is the negative prognostic impact of signet ring cell histology maintained in early gastric adenocarcinoma? Surgery. 2013;154:1093-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim JP, Kim SC, Yang HK. Prognostic significance of signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Surg Oncol. 1994;3:221-227. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Li C, Kim S, Lai JF, Hyung WJ, Choi WH, Choi SH, Noh SH. Advanced gastric carcinoma with signet ring cell histology. Oncology. 2007;72:64-68. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Piessen G, Messager M, Leteurtre E, Jean-Pierre T, Mariette C. Signet ring cell histology is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma regardless of tumoral clinical presentation. Ann Surg. 2009;250:878-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10-24. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Akobeng AK. Understanding diagnostic tests 3: Receiver operating characteristic curves. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:644-647. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Fuchigami T, Kuwano Y, Iwashita A, Tominaga M, Iida M, Yao T. Diagnostic problems in minute gastric cancer, chiefly from a standpoint of radiography. Stomach Intest. 1988;23:741-756 (in Japanese). |