Published online Jun 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i6.254

Revised: February 19, 2014

Accepted: May 16, 2014

Published online: June 16, 2014

Processing time: 192 Days and 13.3 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of undiluted N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate plus methacryloxysulfolane (NBCM) as a prophylactic treatment for gastric varices (GV) bleeding.

METHODS: This prospective study was conducted at a single tertiary-care teaching hospital between October 2009 and March 2013. Patients with portal hypertension (PH) and GV, with no active gastrointestinal bleeding, were enrolled in primary prophylactic treatment with NBCM injection without lipiodol dilution. Initial diagnosis of GV was based on endoscopy and confirmed with endosonography (EUS); the same procedure was used after treatment to confirm eradication of GV. After puncturing the GV with a regular injection needle, 1 mL of undiluted NBCM was injected intranasally into GV. The injection was repeated as necessary to achieve eradication or until a maximum total volume of 3 mL of NBCM had been injected. Patients were followed clinically and evaluated with endoscopy at 3, 6 and 12 mo. Later follow-ups were performed yearly. The main outcome measures were efficacy (GV eradication), safety (adverse events related to cyanoacrylate injection), recurrence, bleeding from GV and mortality related to GV treatment.

RESULTS: A total of 20 patients (15 male) with PH and GV were enrolled in the study and treated with undiluted NBCM injection. Only 2 (10%) patients had no esophageal varices (EV); 18 (90%) patients were treated with endoscopic band ligation to eradicate EV before inclusion in the study. The patients were followed clinically and endoscopically for a median of 31 mo (range: 6-40 mo). Eradication of GV was observed in all patients (13 patients were treated with 1 session and 7 patients with 2 sessions), with a maximum injected volume of 2 mL NBCM. One patient had GV recurrence, confirmed by EUS, at 6-mo follow-up, and another had late recurrence with GV bleeding after 35 mo of follow-up; overall, GV recurrence was observed in 2 patients (10%), after 6 and 35 mo of follow-up, and GV bleeding rate was 5% (1 patient). Mild epigastric pain was reported by 3 patients (15%). No mortality or major complications, including embolism, or damage to equipment were observed.

CONCLUSION: Endoscopic injection with NBCM, without lipiodol, may be a safe and effective treatment for primary prophylaxis of gastric variceal bleeding.

Core tip: In this prospective study, a total of 20 patients with portal hypertension and gastric varices (GV) were referred for primary prophylaxis of GV bleeding with endoscopic injection of N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate plus methacryloxysulfolane (NBCM) without lipiodol dilution. Eradication of GV was observed in all patients. Overall, GV recurrence confirmed by endosonography was observed in 2 patients (10%), after 6 and 35 mo of follow-up. The prevalence of GV bleeding was 5% (1/20 patients). No major complications, such as embolism occurrence or death, were observed. Undiluted NBCM may be a safe and effective prophylactic against GV bleeding.

- Citation: Franco MC, Gomes GF, Nakao FS, de Paulo GA, Ferrari Jr AP, Libera Jr ED. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic prophylactic treatment with undiluted cyanoacrylate for gastric varices. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(6): 254-259

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i6/254.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i6.254

Gastric varices (GV) are less common than esophageal varices (EV) and are estimated to be present in approximately 20% of patients with portal hypertension (PH). Risk of rupture is lower for GV than EV, however GV rupture can be extremely severe and difficult to control, and is associated with higher mortality than EV bleeding (25%-45%)[1].

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a very sensitive tool for GV detection[2]. It is also very useful for the assessment of GV obliteration with tissue adhesive injection and predicting recurrence of varices[3,4].

Since its introduction in the 1980s, endoscopic therapy with cyanoacrylate (CYA) improved the treatment of GV bleeding, achieving hemostasis rates of 89% to 100%, and reducing the rate of recurrent bleeding to below 30%[5,6]. Treatment of GV using glue injection is a well-established procedure. The most commonly used preparation of CYA is N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl®; B. Braun, Germany) diluted with lipiodol (Lipiodol Ultra Fluid®; Guerbert Roissy, France). The adverse events associated with CYA injection are usually minor (fever and mild abdominal pain); however, treatment can be associated with major and potentially life-threatening adverse events, usually related to peripheral embolization of polymerized glue, such as pulmonary embolism, splenic vein and portal vein thrombosis, splenic infarction and recurrent sepsis[7].

Glubran 2® (GEM; Viareggio, Italy) is a preparation of N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate plus methacryloxysulfolane (NBCM). NBCM has a longer polymerization time than pure N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate and does not usually require dilution with lipiodol[8]. NBCM seems to be as safe and effective as the combination of N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate and lipiodol for GV obliteration[9].

Our study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of endoscopic injection of NBCM without lipiodol as a prophylactic treatment for GV bleeding.

This prospective study was conducted between October 2009 and March 2013 at São Paulo Hospital, Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil, a tertiary-care teaching hospital. All patients gave written informed consent before enrollment. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution and was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects.

The following outcomes were analyzed: efficacy (GV eradication); safety (adverse events related to cyanoacrylate injection); GV recurrence; GV bleeding and mortality related to GV treatment.

Patients with PH and large GV (> 10 mm) and no previous GV bleeding were eligible. Patients were followed clinically and endoscopically. Patient age varied from 18 to 75 years. Exclusion criteria were prior endoscopic treatment for GV, history of hepatocellular carcinoma, pregnancy.

Diagnosis of PH and liver disease was based on physical examination, biochemical tests, imaging studies including Doppler evaluation of the splenoportal axis and histological evidence. Patients were classified according to the Child-Pugh classification as having class A, B, or C liver disease.

All endoscopic procedures were performed under conscious sedation using the standard technique. Patients with esophageal varices who were high risk for bleeding underwent esophageal variceal eradication with endoscopic band ligation (EBL) prior to GV treatment. Sarin’s classification[1] was used to classify GV as type 1 gastroesophageal varices (GOV-1), type 2 gastroesophageal varices (GOV-2), type 1 isolated gastric varices (IGV-1) or type 2 isolated gastric varices (IGV-2); Hashizume’s schema[10] was used to classify the form of GV as tortuous (F1), nodular (F2) or tumorous (F3) and the presence of red color signs was recorded. Presence and severity of portal hypertensive gastropathy[11] were also documented. An EUS examination was performed to confirm the presence of GV.

GV puncture, preferentially at the center of the varix, was performed using a regular injection catheter (19 gauge needle), filled with distilled water. Once the intravariceal position of the needle was confirmed, 1 mL of undiluted NBCM was injected followed by enough distilled water to flush all the glue into the GV. The needle was then removed. If necessary, glue injection was repeated at a subsequent session (at 3 mo), up to a maximum injected volume of 2 mL of NBCM.

GV eradication was assessed by endoscopically detectable features, no varices, residual scar or residual hard varices - assessed by touching with closed forceps - and EUS was used to confirm that there was no blood flow into residual varices. A linear array echoendoscope (EG-530 UT; Fujinon, Saitama, Japan) with VP4400 processor (Fujinon; Saitama, Japan) or SU-7000 ultrasonic processor (Fujinon; Saitama, Japan) was used to perform EUS. Endoscopic follow-up was performed at 3-mo intervals until GV eradication was observed; subsequent reevaluations were made at 3, 6 and 12 mo. Later follow-ups were performed yearly. Any clinical suspicion of gastrointestinal bleeding prompted an endoscopic examination.

Quantitative variables were expressed as means ± SD or medians (ranges). Qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 for Windows.

A total of 20 patients with PH and large GV were included in this study. Demographic characteristics of patients are listed in Table 1. According to the Child-Pugh classification 13 (65%) patients had class A disease, and 7 (35%) class B. We attributed the higher than normal proportion of patients with Child-Pugh A to the design of the study, which selected patients for primary prophylaxis of GV bleeding. Ten patients had a history of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGB), due to EV bleeding. Eighteen (90%) patients underwent endoscopic treatment with EBL to eradicate EV before the beginning of the study; the remaining patients had no EV. Twelve patients were taking Propranolol. Most patients presented with GV type GOV1. The endoscopic characteristics of patients are listed in Table 2.

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 20) |

| Mean age in years | 47.35 ± 11.37 |

| Male | 15 (75) |

| Etiology | |

| Viral | 9 (45) |

| Alcohol | 5 (25) |

| Schistosomiasis | 2 (10) |

| Other | 4 (20) |

| Child-Pugh class | |

| A | 13 (65) |

| B | 7 (35) |

| Prior history of UGB | 10 (50) |

| Eradication of EV | 18 (90) |

| Propranolol use | 12 (60) |

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 20) |

| GV Classification | |

| GOV1 | 13 (65) |

| GOV2 | 3 (15) |

| IGV1 | 4 (20) |

| Form of GV | |

| F1 | 7 (35) |

| F2 or F3 | 13 (65) |

| PHG | |

| Mild | 16 (80) |

| Severe | 4 (20) |

| RCS | 4 (20) |

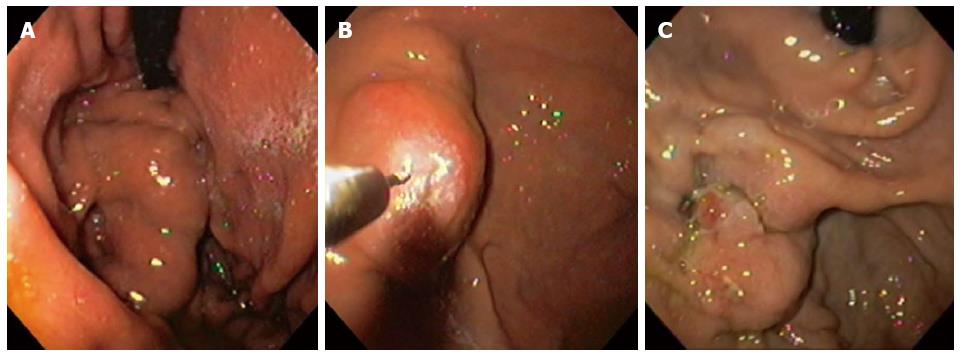

After treatment with undiluted NBCM GV eradication was observed in all patients (Table 3). GV obliteration was achieved in 1 session in 13 (65%) patients and in 2 sessions in 7 (35%) patients, with a mean NBCM volume of 1.37 mL (SD = ± 0.48) (Figure 1). Eighteen patients underwent EUS before CYA injection and GV was confirmed in all patients; 12 (66%) had perigastric collaterals, 9 (50%) had paragastric collaterals and 5 (28%) had perforating veins. Eradication of GV after treatment was confirmed in 18 patients using EUS. In two patients GV eradication was based on endoscopic criteria, without EUS evaluation. Only 1 (5%) patient experienced GV recurrence, confirmed by EUS, at 6-mo follow-up. He had hepatitis C infection (Child-Pugh A), and large (F2) type 2 gastroesophageal varices with red spots.

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 20) |

| GV eradication | 20 (100) |

| Number of sessions | |

| 1 | 13 (65) |

| 2 | 7 (35) |

| Mean volume NBCM injected in mL | 1.37 ± 0.48 |

| Recurrence rate | |

| 3 mo | 0 |

| 6 mo | 1 (5) |

| > 2 yr | 1 (5) |

| Total | 2 (10) |

| Median follow-up in months (range) | 31 (6-40) |

| Late bleeding rate | 1 (5) |

| Minor adverse events1 | 3 (15) |

| Major adverse events | 0 |

| Overall mortality rate | 0 |

A late endoscopic follow-up, at least 2 years after eradication, was performed in 16 (80%) patients. Late recurrence of GV, confirmed by EUS, was observed in one patient at a 35-mo follow-up. This patient had alcohol-related liver disease (Child-Pugh B), large (F2) type 1 gastroesophageal varices at the first endoscopic evaluation. He presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding with no significant clinical consequences, and was treated with a second CYA injection and suffered no adverse events. Four patients were lost during follow-up, although none were readmitted to our hospital with GV bleeding. Overall, the GV recurrence rate was 10% and the GV bleeding rate was 5%, over a median of 31 mo (range: 6-40 mo).

No mortality was observed during our study. Mild epigastric pain was reported by 3 patients (15%). No major adverse events (systemic embolism, sepsis or gastrointestinal bleeding due CYA injection) or damage to equipment were observed (Table 3).

Endoscopic therapies for esophageal varices, such as band ligation and injection of sclerosant agents, have also been used to treat GV bleeding. However the results in terms of hemostasis, rebleeding and GV obliteration are poor compared with CYA injection[5,12], so endoscopic CYA injection has been recommended as an initial treatment for acute GV bleeding in recent consensus and guidelines[13-15]. Treatment of GV bleeding using transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) has also been studied; although TIPS is as safe and clinically effective as CYA injection, TIPS placement is associated with higher long-term morbidity, due to increased incidence of encephalopathy, and it is also more expensive[16].

There have been recent reports of increased survival with primary and secondary prophylaxis of GV bleeding with CYA injection[17,18], but only a few studies have evaluated the safety and long-term efficacy of prophylactic CYA injection[19,20]. In this study, prophylactic GV eradication was achieved in all patients with NBCM injection. The GV recurrence rate was 10% (2/20) and the prevalence of late GV bleeding was 5% (1/20). There were no reported deaths related to GV bleeding during follow-up. These results are similar to previously published reports on prophylactic treatment of GV with Histoacryl® plus lipiodol over follow-up periods of up to 2 years. Previous studies reported eradication rates ranging from 95% to 100%; GV recurrence rates ranging from 4.3% to 14.0%; GV rebleeding rates from 4.3% to 8.0% and GV-associated mortality rates up to 4.3%[19,20].

Greater dilution of CYA with lipiodol seems to increase the risk of embolization[21]. Most reported major adverse events after CYA injection, such as distal embolization and death, occurred in patients in whom this combination was used[7,21,22].

Dhiman et al[23] reported no embolic events after switching from CYA diluted with lipiodol (1:1) to undiluted CYA injection as a treatment for GV bleeding. Similarly Kumar et al[24] reported no clinically significant embolization in 87 patients treated for GV bleeding using 261 injections of undiluted CYA.

NBCM (Glubran 2®) does not require dilution with lipiodol because it polymerizes a little more slowly than pure N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl®)[8]. One may hypothesize that after injection into the varix NBCM in contact with blood polymerizes faster than N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate diluted with lipiodol. Such fast local intravasal polymerization of undiluted NBCM might be associated with reduced incidence of embolic events. Further research is required to investigate this hypothesis as there is currently no published empirical evidence.

In our study there were no major adverse events over 27 injections of undiluted NBCM in 20 patients for GV prophylactic eradication. Saracco et al[25] reported a single fatal systemic embolism after treatment of GV bleeding with undiluted NBCM using 2 mL of NBCM in one session, in a patient with idiopathic PH. It is recommended that CYA be used as 1 mL injections per session, because larger injected volumes are associated with a higher risk of peripheral embolization[26].

We used EUS to assess GV obliteration and recurrence after treatment with NBCM injections. Flow in residual GV, which would indicate that further CYA injection were required[27], can be detected using EUS. EUS has also been used to support GV eradication by CYA injection into gastric perforating veins, a method which appears to be safe and effective, with a low recurrent bleeding rate[28].

This study is significant because there are only few reports on the efficacy and long-term safety of prophylactic CYA injection for GV[19,20]. Furthermore, this study is the first to have evaluated the feasibility, efficacy and long-term safety of NBCM as a prophylactic treatment for GV bleeding in adults.

In conclusion, although our findings are subject to some limitations (small series, patients with good liver function, one arm design in a single institution, and loss to follow up of some patients), our results suggest that endoscopic injection with NBCM, without lipiodol, may be a safe and effective primary prophylactic for gastric variceal bleeding.

Endoscopic cyanoacrylate (CYA) injection has been recommended as initial treatment for gastric varices (GV) acute bleeding. Band ligation and injection of sclerosant agents produce worse outcomes in terms of GV hemostasis and rebleeding than CYA injection. TIPS is associated with increased incidence of encephalopathy.

Although a recent publication of Mishra et al has reported reduced risk of first bleeding and lower mortality with CYN injection, compared with beta-blockers, for prophylactic treatment of large GV, only a few studies have evaluated the safety and long-term efficacy of prophylactic CYA injection.

N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate diluted with lipiodol is the most commonly used CYA preparation used for endoscopic injection into GV, however it is associated with a risk of peripheral embolization of polymerized glue. N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate plus methacryloxysulfolane (NBCM) does not usually require dilution with lipiodol for GV injection, and may be associated with a lower incidence of adverse events. This is the first study to have evaluated the feasibility, efficacy and long-term safety of NBCM as a prophylactic treatment for GV bleeding in adults.

Endoscopic treatment with CYN injection is low cost, widely available, and not hard to do.

NBCM is a preparation of N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate with methacryloxysulfolane. NBCM has a longer polymerization time than pure N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate.

It is interesting that this study was the first to determine the efficacy and safety of prophylactic treatment by undiluted N-butyl-2 Cyanoacrylate plus Methacryloxysulfolane (NBCM) for gastric varices. And the authors concluded endoscopic injection with NBCM, without lipiodol, may be a safe and effective treatment for primary prophylaxis of gastric varices bleeding.

P- Reviewers: Baba H, Thakur B S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343-1349. |

| 2. | Lee YT, Chan FK, Ching JY, Lai CW, Leung VK, Chung SC, Sung JJ. Diagnosis of gastroesophageal varices and portal collateral venous abnormalities by endosonography in cirrhotic patients. Endoscopy. 2002;34:391-398. |

| 3. | Lahoti S, Catalano MF, Alcocer E, Hogan WJ, Geenen JE. Obliteration of esophageal varices using EUS-guided sclerotherapy with color Doppler. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:331-333. |

| 4. | Irisawa A, Saito A, Obara K, Shibukawa G, Takagi T, Shishido H, Sakamoto H, Sato Y, Kasukawa R. Endoscopic recurrence of esophageal varices is associated with the specific EUS abnormalities: severe periesophageal collateral veins and large perforating veins. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:77-84. |

| 5. | Sarin SK, Jain AK, Jain M, Gupta R. A randomized controlled trial of cyanoacrylate versus alcohol injection in patients with isolated fundic varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1010-1015. |

| 6. | Rengstorff DS, Binmoeller KF. A pilot study of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate injection for treatment of gastric fundal varices in humans. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:553-558. |

| 7. | Martins Santos MM, Correia LP, Rodrigues RA, Lenz Tolentino LH, Ferrari AP, Della Libera E. Splenic artery embolization and infarction after cyanoacrylate injection for esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:1088-1090. |

| 8. | Cameron R, Binmoeller KF. Cyanoacrylate applications in the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:846-857. |

| 9. | Rivet C, Robles-Medranda C, Dumortier J, Le Gall C, Ponchon T, Lachaux A. Endoscopic treatment of gastroesophageal varices in young infants with cyanoacrylate glue: a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1034-1038. |

| 10. | Hashizume M, Kitano S, Yamaga H, Koyanagi N, Sugimachi K. Endoscopic classification of gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:276-280. |

| 11. | McCormack TT, Sims J, Eyre-Brook I, Kennedy H, Goepel J, Johnson AG, Triger DR. Gastric lesions in portal hypertension: inflammatory gastritis or congestive gastropathy? Gut. 1985;26:1226-1232. |

| 12. | Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Chen MH, Chiang HT. A prospective, randomized trial of butyl cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation in the management of bleeding gastric varices. Hepatology. 2001;33:1060-1064. |

| 13. | de Franchis R. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762-768. |

| 14. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938. |

| 15. | Qureshi W, Adler DG, Davila R, Egan J, Hirota W, Leighton J, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli R, Wheeler-Harbaugh J. ASGE Guideline: the role of endoscopy in the management of variceal hemorrhage, updated July 2005. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:651-655. |

| 16. | Procaccini NJ, Al-Osaimi AM, Northup P, Argo C, Caldwell SH. Endoscopic cyanoacrylate versus transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for gastric variceal bleeding: a single-center U.S. analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:881-887. |

| 17. | Mishra SR, Chander Sharma B, Kumar A, Sarin SK. Endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection versus beta-blocker for secondary prophylaxis of gastric variceal bleed: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2010;59:729-735. |

| 18. | Mishra SR, Sharma BC, Kumar A, Sarin SK. Primary prophylaxis of gastric variceal bleeding comparing cyanoacrylate injection and beta-blockers: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2011;54:1161-1167. |

| 19. | Martins FP, Macedo EP, Paulo GA, Nakao FS, Ardengh JC, Ferrari AP. Endoscopic follow-up of cyanoacrylate obliteration of gastric varices. Arq Gastroenterol. 2009;46:81-84. |

| 20. | Chang YJ, Park JJ, Joo MK, Lee BJ, Yun JW, Yoon DW, Kim JH, Yeon JE, Kim JS, Byun KS. Long-term outcomes of prophylactic endoscopic histoacryl injection for gastric varices with a high risk of bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2391-2397. |

| 21. | Kok K, Bond RP, Duncan IC, Fourie PA, Ziady C, van den Bogaerde JB, van der Merwe SW. Distal embolization and local vessel wall ulceration after gastric variceal obliteration with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate: a case report and review of the literature. Endoscopy. 2004;36:442-446. |

| 22. | Tan YM, Goh KL, Kamarulzaman A, Tan PS, Ranjeev P, Salem O, Vasudevan AE, Rosaida MS, Rosmawati M, Tan LH. Multiple systemic embolisms with septicemia after gastric variceal obliteration with cyanoacrylate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:276-278. |

| 23. | Dhiman RK, Chawla Y, Taneja S, Biswas R, Sharma TR, Dilawari JB. Endoscopic sclerotherapy of gastric variceal bleeding with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:222-227. |

| 24. | Kumar A, Singh S, Madan K, Garg PK, Acharya SK. Undiluted N-butyl cyanoacrylate is safe and effective for gastric variceal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:721-727. |

| 25. | Saracco G, Giordanino C, Roberto N, Ezio D, Luca T, Caronna S, Carucci P, De Bernardi Venon W, Barletti C, Bruno M. Fatal multiple systemic embolisms after injection of cyanoacrylate in bleeding gastric varices of a patient who was noncirrhotic but with idiopathic portal hypertension. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:345-347. |

| 26. | Soehendra N, Grimm H, Nam VC, Berger B. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate: a supplement to endoscopic sclerotherapy. Endoscopy. 1987;19:221-224. |

| 27. | Lee YT, Chan FK, Ng EK, Leung VK, Law KB, Yung MY, Chung SC, Sung JJ. EUS-guided injection of cyanoacrylate for bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:168-174. |

| 28. | Romero-Castro R, Pellicer-Bautista FJ, Jimenez-Saenz M, Marcos-Sanchez F, Caunedo-Alvarez A, Ortiz-Moyano C, Gomez-Parra M, Herrerias-Gutierrez JM. EUS-guided injection of cyanoacrylate in perforating feeding veins in gastric varices: results in 5 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:402-407. |