Published online Apr 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i4.169

Revised: December 20, 2012

Accepted: January 23, 2013

Published online: April 16, 2013

Processing time: 178 Days and 15.6 Hours

AIM: To summarize the magnitude and time trends of endoscopy-related claims and to compare total malpractice indemnity according to specialty and procedure.

METHODS: We obtained data from a comprehensive database of closed claims from a trade association of professional liability insurance carriers, representing over 60% of practicing United States physicians. Total payments by procedure and year were calculated, and were adjusted for inflation (using the Consumer Price Index) to 2008 dollars. Time series analysis was performed to assess changes in the total value of claims for each type of procedure over time.

RESULTS: There were 1901 endoscopy-related closed claims against all providers from 1985 to 2008. The specialties include: internal medicine (n = 766), gastroenterology (n = 562), general surgery (n = 231), general and family practice (n = 101), colorectal surgery (n = 87), other specialties (n = 132), and unknown (n = 22). Colonoscopy represented the highest frequencies of closed claims (n = 788) and the highest total indemnities ($54 093 000). In terms of mean claims payment, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) ranked the highest ($374 794) per claim. Internists had the highest number of total claims (n = 766) and total claim payment ($70 730 101). Only total claim payments for colonoscopy and ERCP seem to have increased over time. Indeed, there was an average increase of 15.5% per year for colonoscopy and 21.9% per year for ERCP after adjusting for inflation.

CONCLUSION: There appear to be differences in malpractice coverage costs among specialties and the type of endoscopic procedure. There is also evidence for secular trend in total claim payments, with colonoscopy and ERCP costs rising yearly even after adjusting for inflation.

- Citation: Hernandez LV, Klyve D, Regenbogen SE. Malpractice claims for endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(4): 169-173

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i4/169.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i4.169

Endoscopies are being performed at an increasing rate for the last decade[1]. Endoscopic procedures are also becoming more complicated as interventional techniques are used more widely. Despite increasing national awareness of medical errors, and the high costs of associated malpractice, there is a lack of data sources from which to understand the incidence and trends of errors resulting in major injuries during endoscopic procedures.

Traditionally, the main source of information on endoscopy-related errors comes from institutional morbidity and mortality conferences. However, this and other self-reporting methods are known to underestimate the true incidence of complications[2]. In general and vascular surgery, the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program has become a platform for validated, risk-adjusted outcome comparisons between institutions, however, only a select minority of hospitals have implemented the program, and similar registries have not been as widely accepted in other interventional subspecialties.

Aligned with value-based purchasing by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the American College of Gastroenterology and the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy have advocated for measuring endoscopy quality indicators. As preventing errors is linked to quality, endoscopists increasingly are recognizing the importance of understanding and benchmarking endoscopic errors at a national level.

Claims in malpractice litigation offer an opportunity to study major iatrogenic injuries. In a study by Studdert et al[3], trained reviewers examined 1500 closed claims of alleged medical injuries from negligence and found that 97% of closed claims involved injury, of which 63% resulted from error. In another study of surgical claims[4], technical errors accounted for about half of the cases. A study by Conklin et al[5] focusing on gastroenterologists showed that 25% of claims were due to improper performance of an endoscopic procedure, but further information such as type of endoscopies were not described. In addition, endoscopies in the United States are also performed by non-gastroenterologists, and there have been no studies to our knowledge that have looked into malpractice information in this population.

Our aim is to provide a synopsis of the magnitude and time trends of endoscopy-related claims and to compare total malpractice indemnity according to specialty and procedure.

We obtained summary-level data from a comprehensive database of closed claims against physicians who are members of the Physicians Insurers Association of America (PIAA), which is a trade association of professional liability companies owned by physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers. PIAA, which has the largest database of malpractice claims in the nation, insures over 300 000 doctors and 1300 hospitals, representing over 60% of United States doctors and underwrites 46% or $5.2 billion of the total medical liability industry premium. The closed claims represented data from all 50 states from January 1985 up to December 2008.

Due to confidentiality agreements with member companies, the PIAA is unable to provide specific geographic information. The de-identified data is therefore not traceable to the provider. PIAA collects data based on information provided by the member liability insurance company which covered the physician. The professional coder from the liability insurance company codes the condition, care rendered, and outcome by complying with PIAA guidelines. Inclusion criteria were all endoscopic procedures (esophagogastroduodenoscopy, EGD; colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy; rigid proctosigmoidoscopy; endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, ERCP; and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, PEG) that resulted in closed claims during the study period. There was no identifiable code available for endoscopic ultrasound at the time of the study.

Etiologies of claims were categorized by PIAA coders according to a priori definition of errors. Improper performance is defined as an endoscopic procedure that was done incorrectly. An example is an ERCP with improperly placed stent that led to a fatal complication. Diagnosis error is resulted from failure to diagnose or providing an incorrect diagnosis. Data on total and average payment to plaintiffs for claims were provided according to specialty but not to type of procedure.

A claim is a written demand for compensation for medical injury within the statute of limitations of a jurisdiction. A claim can be closed in one of four possible ways: (1) at the end of a trial by final judgment; (2) at any point before the end of the trial when the case is settled with a payment; (3) when the case is voluntarily dropped by the plaintiff; or (4) if the defendant successfully files a motion to dismiss the case when there is a valid legal basis to do so. Thus, a claim may be closed with or without indemnity payment, which is defined as the sum of money paid in compensation for injury.

Total payments by procedure and year were calculated, and were adjusted for inflation (using the consumer price index) to 2008 dollars. We then focused on time series analysis to see how the total value of claims for each type of procedure changed over time. Two models were used: a linear least-squares regression model, which will show the average absolute growth in total claims (in adjusted dollars) per year; and an exponential least-squares regression model, which will derive the average percent growth. The ability of these models to describe the data is captured in the value of R2. A value of zero means that the model has no explanatory power, while a value of one indicates that the total claim value can be perfectly deduced from the year.

There were 1901 endoscopy-related closed claims against all providers from 1985 to 2008. The specialties include: internal medicine (n = 766), gastroenterology (n = 562), general surgery (n = 231), general and family practice (n = 101), colorectal surgery (n = 87), other specialties (n = 132), and unknown (n = 22). Over 98% resulted in physical injury, which was generally severe (25.8% resulted in deaths and 40.7% resulted in significant or major disability). Close to 70% of all cases were dropped by the plaintiff or dismissed by the court before the trial was concluded. An additional 5% of cases were won by the defendant at trial.

Closed claims against gastroenterologists from 1985 to 2006 that involve endoscopies are shown in Table 1. The majority resulted from improper performance of an endoscopic procedure, followed by diagnosis error. Right and left-sided colon cancers were almost equally represented. Closed claims involving colon cancer according to location were as follows: cecum (n = 3), hepatic flexure (n = 2), transverse colon (n = 2), rectosigmoid junction (n = 6), rectum (n = 3), and unspecified location (n = 5).

| Etiology of claims | Frequency (n = 341) |

| Improper performance | 175 (51.3) |

| Diagnosis error (failure, incorrect) | 59 (17.3) |

| Meritless (no clear evidence) | 35 (10.3) |

| Failure to supervise or monitor | 17 (4.9) |

| Not indicated/contraindicated | 14 (4.1) |

| Failure to recognize complication | 12 (3.5) |

| Failure to communicate with patient | 6 (1.8) |

| Delay in performance | 4 (1.2) |

| Others | 19 (5.6) |

Colonoscopy, followed by sigmoidoscopy (flexible and rigid) represented the highest frequencies of closed claims and the highest total indemnities (Table 2). In terms of average cost per claim, ERCP ranked the highest.

| Procedure | Closed claims | Total paid claims | Total claim payments ($) | Mean claim payments ($) |

| Colonoscopy | 788 | 216 | 54 093 000 | 250 430.56 |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | 513 | 182 | 28 674 000 | 157 549.45 |

| ERCP | 217 | 67 | 25 207 000 | 376 223.88 |

| Rigid proctoscopy | 125 | 51 | 15 726 000 | 308 352.94 |

| EGD | 209 | 47 | 9 666 000 | 205 659.57 |

| PEG | 49 | 7 | 2 598 000 | 371 142.86 |

| Internal medicine | 766 | - | 70 730 101 | 261 963 |

| Gastroenterology | 562 | - | 30 841 008 | 250 740 |

| General surgery | 231 | - | 13 305 060 | 187 395 |

| General/family practice | 101 | - | 7 288 674 | 186 889 |

| Colorectal surgery | 87 | - | 6 593 000 | 286 652 |

| Other specialties | 154 | - | 7 206 157 | 163 776 |

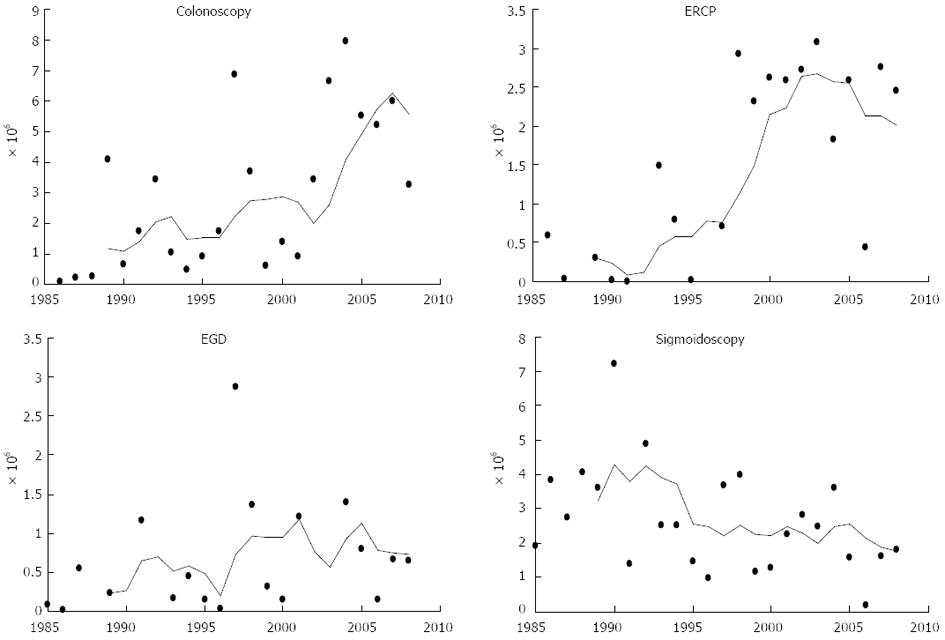

Table 2 shows the average and total indemnity comparing the various specialties that perform endoscopies. Internists had the highest number of total claims and total claim payment. Figure 1 shows the total claim payments over time according to procedure. For procedures such as EGD which sometimes have only one or two closed claims per year, one very large payment can skew these averages. Colonoscopy and ERCP have had many more paid claims, and for these procedures there is a clear increase in average claim payment. Indeed, there appears to have been an average increase of 15.5% per year for colonoscopy and 21.9% per year for ERCP after adjusting for inflation.

In the time period covered, closed claims for PEG procedures were recorded during only six of the years studied, thus there was insufficient data for analysis. For the other procedures, an exponential model fit the data better than a linear model in three of the four cases. Table 3 shows both the absolute and percentage increase (in real dollars) of the average value of claims. Of note, the total sigmoidoscopy claims have been declining on average since 1985. The data from which these regression figures were calculated is shown in Figure 1.

| Linear increase/yr ($) | Model R2 | Expon increase/yr, % | Model R2 | |

| Colonoscopy | 229 000 | 0.3976 | 12.59 | 0.4874 |

| ERCP | 122 000 | 0.5098 | 19.06 | 0.4076 |

| EGD | 23 000 | 0.0567 | 7.53 | 0.1697 |

| Sigmoidoscopy | -93 000 | 0.1873 | -4.6 | 0.1938 |

Our study shows that from the standpoint of insurers, internists who perform endoscopies had the highest total claim payment, costing over twice than gastroenterologists in terms of compensation for negligence. The largest total indemnities resulted from colonoscopies and sigmoidoscopies, but only colonoscopy and ERCP have been increasing over time. This could reflect the increasing number of colonoscopies performed per year and the increasing number of endoscopists who perform ERCPs.

The annual cost of the United States medical liability system is estimated to be $55.6 billion[6]. According to the United States Government Accountability Office, the primary driver in medical liability insurance industry economics is the rising average cost of indemnity, which leads to rising premiums that has affected gastroenterologists and non-gastroenterologists alike. Although the specialty of gastroenterology has always been viewed as low-risk for medical malpractice lawsuit, a recent seminal study[7] has shown that gastroenterology ranks six out of 25, before obstetrics and gynecology, in terms of proportion of physicians facing malpractice claims.

Our data have several limitations. PIAA produces summary data making us unable to cross-reference variables and to assess inter-relationships between any predictors. There is no information on individuals who do not sue. However, these claims represent the most significant injuries that merit attention. Also, no chart validation studies were performed to confirm robustness of findings. The denominator, or the total number of physicians per specialty who perform endoscopies is unknown, so our data reflect frequencies and not proportions. Internists had higher cost per claim, but we do not know if there is higher cost per insured internist because the denominator is not available. It is possible that gastroenterologists were misclassified as internists, but sued doctors self-classified themselves, of which the PIAA coders used in data collecting. Thus, we believe a gastroenterologist would have no incentive to classify him or herself as an internist.

There are also several factors other than legal merit that determines whether claims are paid in litigation, such as severity of injury. Thus, we realize that the legal definition of negligence (or failure to use reasonable care) is not necessarily synonymous with genuine error in all instances. Typically, there is a hierarchy as to what people consider preventable injury-there are those caused by error, of which some involved negligence, but usually all negligence involves error.

However despite our limited data resource, our study provides useful, unprecedented information on litigations related to endoscopy. All closed claims are likely captured by the collaborative PIAA database. Because of the economics of litigation, these cases typically represent those involving serious injuries.

In summary, closed malpractice claims data yielded important information on alleged injuries resulting from endoscopy. We found discrepancies in malpractice costs among specialties and the type of procedure. There is also evidence for secular trend in total claim payments, with colonoscopy and ERCP costs rising yearly after adjusting for inflation.

Malpractice insurers might use this information to scale their premiums according to both specialty and type of endoscopy performed, allowing a risk differential payment structure. They may also incentivize simulation training, credentialing, or other regulatory strategies, and to sponsor safety improvement efforts to reduce their exposure. Gastroenterologists are to be held accountable for managing risks of errors[8] in endoscopy by adhering to standards of practice, especially when performing ERCP[9,10] (adequate training and yearly volume) or colonoscopy[11] (minimize colon cancer miss rates and ensure proper documentation). The limitations of our retrospective data highlight the need for a comprehensive, perhaps even a prospective, nationwide database at an individual level to capture the incidence rates of major adverse events and errors, and to design interventions that can reduce iatrogenic injuries resulting from substandard endoscopy.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Atul Gawande of the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) in Boston, MA who facilitated our collaboration at HSPH. We also thank Ms. Jacque Dresen for assisting in the manuscript.

Little is known about major endoscopy-related errors categorized by procedure and specialty, and time trends.

In general and vascular surgery, the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program has become a platform for validated, risk-adjusted outcome comparisons between institutions, however only a select minority of hospitals have implemented the program, and it has not been highly developed for other fields that involve procedures.

Authors obtained summary-level data from a comprehensive database of closed claims against physicians who are members of the Physicians Insurers Association of America (PIAA), which is a trade association of professional liability companies owned by physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers.

Their study provides useful, unprecedented information on litigations related to endoscopy. All closed claims are likely captured by the collaborative PIAA database. Because of the economics of litigation, these cases typically represent those involving serious injuries.

In this study the investigators compare and contrast major endoscopy-related errors for which insurance claims were filed, categorized by procedure and specialty, and time trends. They also compared total malpractice indemnity by specialty and procedure. The data was acquired from a database of closed claims from a trade association of professional liability insurance carriers, and covers approximately 60% of United States physicians in all 50 states. A total of 1901 endoscopy-related closed claims were found against all providers from 1985 to 2008. Colonoscopy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) had highest dollar value per claim. Internists had the highest number of total claims and total claim payment. Corrected for inflation, only total claim payments for colonoscopy and ERCP seem to have increased over time. The study was retrospective and showed rates, not proportions.

P- Reviewers Vivas S, Ciaccio EJ S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db32.htm. |

| 2. | Hutter MM, Rowell KS, Devaney LA, Sokal SM, Warshaw AL, Abbott WM, Hodin RA. Identification of surgical complications and deaths: an assessment of the traditional surgical morbidity and mortality conference compared with the American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:618-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, Gandhi TK, Kachalia A, Yoon C, Puopolo AL, Brennan TA. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2024-2033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 558] [Cited by in RCA: 457] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Regenbogen SE, Greenberg CC, Studdert DM, Lipsitz SR, Zinner MJ, Gawande AA. Patterns of technical error among surgical malpractice claims: an analysis of strategies to prevent injury to surgical patients. Ann Surg. 2007;246:705-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Conklin LS, Bernstein C, Bartholomew L, Oliva-Hemker M. Medical malpractice in gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:677-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1569-1577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:629-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 738] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Floyd TK. Medical malpractice: trends in litigation. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1822-1825, 1825.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Baron TH, Petersen BT, Mergener K, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffinan B, Jacobson BC, Petrini JL, Safdi MA. Quality indicators for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:892-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cotton PB. Analysis of 59 ERCP lawsuits; mainly about indications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:378-382; quiz 464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:873-885. [PubMed] |