Published online Mar 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i3.81

Revised: November 8, 2012

Accepted: January 23, 2013

Published online: March 16, 2013

AIM: To clarify the efficacy and safety of an endoscopic approach through the minor papilla for the management of pancreatic diseases.

METHODS: This study included 44 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures performed in 34 patients using a minor papilla approach between April 2007 and March 2012. We retrospectively evaluated the clinical profiles of the patients, the endoscopic interventions, short-term outcomes, and complications.

RESULTS: Of 44 ERCPs, 26 were diagnostic ERCP, and 18 were therapeutic ERCP. The most common cause of difficult access to the main pancreatic duct through the major papilla was pancreas divisum followed by distortion of Wirsung’s duct. The overall success rate of minor papilla cannulation was 80% (35/44), which was significantly improved by wire-guided cannulation (P = 0.04). Endoscopic minor papillotomy (EMP) was performed in 17 of 34 patients (50%) using a needle-knife (13/17) or a pull-type papillotome (4/17). EMP with pancreatic stent placement, which was the main therapeutic option for patients with chronic pancreatitis, recurrent acute pancreatitis, and pancreatic pseudocyst, resulted in short-term clinical improvement in 83% of patients. Mild post-ERCP pancreatitis occurred as an early complication in 2 cases (4.5%).

CONCLUSION: The endoscopic minor papilla approach is technically feasible, safe, and effective when the procedure is performed in a high-volume referral center by experienced endoscopists.

- Citation: Fujimori N, Igarashi H, Asou A, Kawabe K, Lee L, Oono T, Nakamura T, Niina Y, Hijioka M, Uchida M, Kotoh K, Nakamura K, Ito T, Takayanagi R. Endoscopic approach through the minor papilla for the management of pancreatic diseases. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(3): 81-88

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i3/81.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i3.81

The endoscopic approach through the major papilla is generally considered the most common and effective method for the management of pancreatic diseases. However, access to the main pancreatic duct (MPD) through the major papilla is sometimes impossible due to pancreas divisum, distortion of Wirsung’s duct, or other causes. When it is difficult to use a major papilla approach in diagnostic or therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), cannulation of the minor papilla is attempted as an alternative method[1]. Endoscopic treatment through the minor papilla, including endoscopic minor papillotomy (EMP) and endoscopic pancreatic stent (EPS) placement, have been developed in previous studies for patients with pancreas divisum[2-6]. For patients with pancreas divisum and recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP), endoscopic treatment through the minor papilla is considered an effective therapeutic option[1]. However, a number of problems associated with these techniques are still unresolved, including the indications for using this approach, the procedures, and the therapeutic efficacy and safety. Therefore, in this study, we reviewed patients who underwent ERCP with a minor papilla approach and evaluated whether this procedure is useful for the management of pancreatic diseases. Herein, we describe a single center experience and review the literature on the endoscopic minor papilla approach.

We retrospectively reviewed our ERCP database to find patients who underwent an endoscopic minor papilla approach at Kyushu University Hospital from April 2007 to March 2012. A total of 1418 ERCPs were performed during the study period, and 44 ERCPs using a minor papilla approach in 34 patients were included in the analysis. There were 19 men and 15 women, and the mean age was 55 (range, 13-79) years. The clinical profiles, endoscopic interventions through the minor papilla, short-term outcome, and complications associated with the endoscopic procedures were evaluated for all patients. Post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP), one of the major complications, was diagnosed on the basis of the criteria proposed by Cotton et al[7]. PEP was defined as pancreatic pain and hyperamylasemia occurring within 24 h of the procedure. Pancreatic pain was defined as persistent pain in the epigastric or periumbilical region. Hyperamylasemia was defined as an increase in serum amylase level to more than 3 times the upper normal limit[7,8]. All patients provided written informed consent for ERCP, including endoscopic treatment.

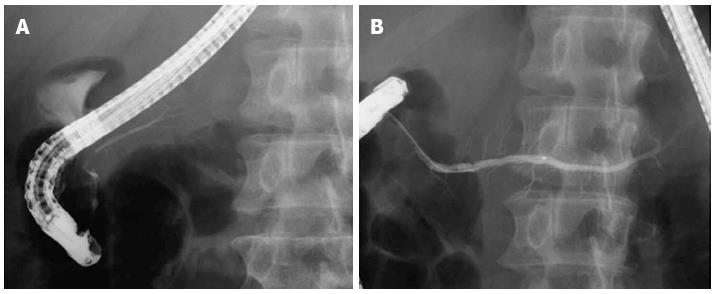

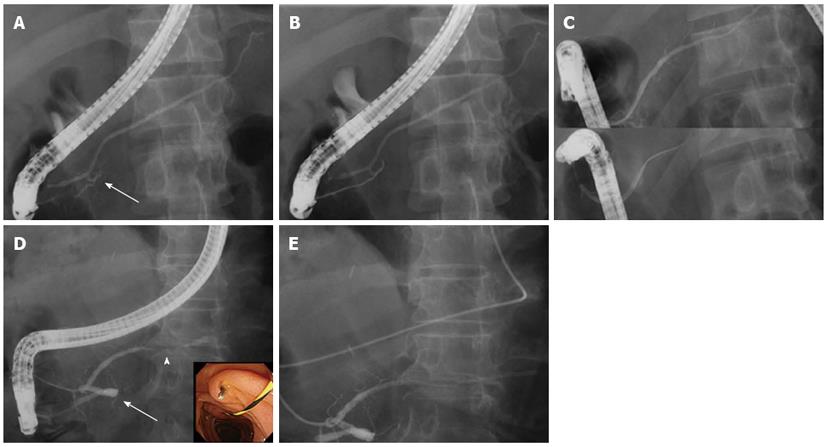

To achieve sedation and duodenal aperistalsis, patients usually received intravenous midazolam (5 mg), pentazocine (7.5 mg), and glucagon (1 mg). A side-viewing duodenoscope (JF-260V; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) was used, and the major papilla was first cannulated with a standard catheter (Tandem XL; Boston Scientific, Boston, MA). When endoscopists judged its access to the MPD through the major papilla difficult due to pancreas divisum, distortion of Wirsung’s duct, or other causes, minor papilla cannulation was attempted. For 1 patient without pancreas divisum, in whom a guidewire was passed retrograde into Wirsung’s duct via the major papilla and antegrade out of the minor papilla, a rendezvous technique was employed[9,10].

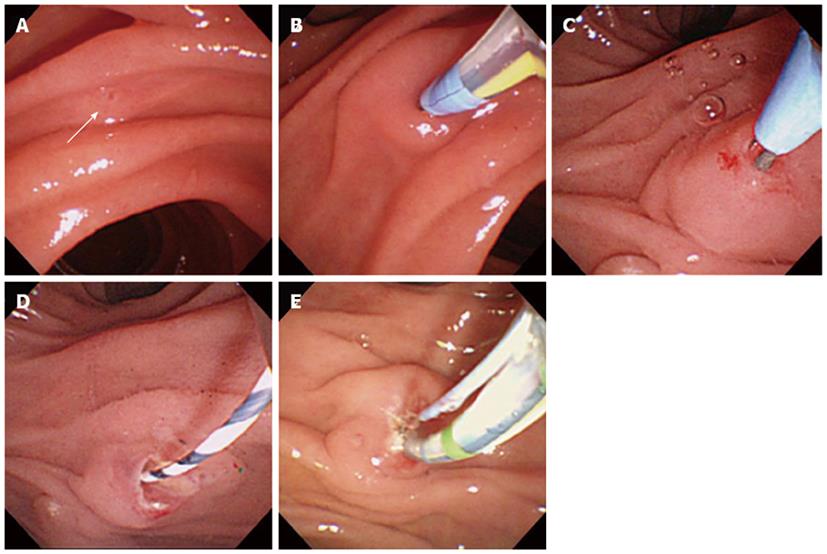

The minor papilla was usually cannulated using a tapered catheter (PR-9Q-1; Olympus Medical Systems) loaded with or without a guidewire (Jagwire; 0.025 inch in diameter, 450 cm in length; Boston Scientific). Since April 2009, we have employed wire-guided cannulation (WGC) to the minor papilla approach. For WGC, a guidewire was advanced into the orifice of the minor papilla, and then the wire was carefully advanced 10-20 mm into Santorini’s duct or until any resistance was encountered (Figure 1A and B)[11]. Subsequently, the cannula was lightly impacted on the minor papilla to obtain a dorsal pancreatogram. After we confirmed the course of Santorini’s duct and the distal MPD, we advanced the guidewire and catheter deeply into the tail of the pancreas.

EMP was performed using a needle-knife (RX Needleknife XL; Boston Scientific) or a pull-type sphincterotome (CleverCut; Olympus Medical Systems, or Autotome; Boston Scientific). A precut papillotomy with the needle-knife over a guidewire was typically performed because the orifice of the minor papilla was usually too small to deeply advance a pull-type sphincterotome (Figure 1C and D). However, when the orifice permitted passage of a pull-type sphincterotome, a standard sphincterotomy was performed (Figure 1E). The extent of the cut was determined by the size of the minor papilla, and generally ranged from 3 to 6 mm.

Following minor papillotomy, a 5 Fr to 7 Fr EPS (Geenen pancreatic stent, 5 to 9 cm in length; Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC) was inserted through the minor papilla as a therapeutic option. An endoscopic nasopancreatic drainage (ENPD) tube (5 Fr; Cook Medical) was inserted through the minor papilla for repeated cytology in diagnostic ERCP, or for pancreatic pseudocyst drainage in therapeutic ERCP. Peroral pancreatoscopy (POPS) (SpyGlass; Boston Scientific) through the minor papilla was performed for the diagnosis of a patient with main-duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN).

Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

From April 2007 to March 2012, 44 ERCPs through the minor papilla were attempted in 34 patients at our institution. Patient characteristics and procedure indications are summarized in Table 1. A total of 1418 ERCPs were performed in our department during the study period; therefore, the rate of approach through the minor papilla was 3.1%. Pancreas divisum was the most common cause of difficult access to the MPD through the major papilla (45%) (Figure 2). Of the 20 cases with pancreas divisum, 17 were complete pancreas divisum and 3 were incomplete pancreas divisum. Other causes of difficult access besides pancreas divisum were, in descending order, distortion (Figure 3), stenosis, and compression of Wirsung’s duct (Table 1). In these cases, a guidewire could not be advanced through the major papilla to the MPD in the tail of the pancreas (Figure 3B and D). Of the 44 ERCPs, 26 were diagnostic (59%) and 18 were therapeutic (41%). The most common indication for diagnostic ERCP was pancreatic cystic neoplasm, such as IPMN. Other indications were autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP), pancreas divisum, RAP, and pancreatic mass, etc. In 3 cases with pancreatic masses, including pancreatic cancer, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, and metastatic pancreatic tumor, it was difficult to make a definite diagnosis by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration, and we consequently performed diagnostic ERCP in these patients. Of the 19 diagnostic ERCP cases with successful cannulation of the minor papilla, 8 included a diagnostic pancreatogram only, 11 underwent aspiration of pure pancreatic juice for cytologic examination, including 4 cases with placement of an ENPD tube for repeated cytology, and 2 cases underwent POPS through the minor papilla and pancreatic juice cytology for the evaluation of main-duct type IPMN. In addition, therapeutic ERCP was performed in patients with chronic pancreatitis (CP), RAP, pancreatic pseudocysts, or MPD injury due to pancreatic trauma. EMP was performed in 17 of 34 patients (50%) with naive minor papilla by using a needle-knife (13 cases) or pull-type papillotome (4 cases).

| Number of patients | 34 |

| Mean age (range) | 55 (13–79) |

| Male/female | 19/15 |

| Patients with pancreas divisum | 16 |

| ERCP sessions through the minor papilla | 44 |

| Total ERCPs during the study period | 1418 |

| Rate of minor papilla approach | 3.10% |

| Causes of difficult access through the major papilla | 44 |

| Pancreas divisum (complete/incomplete) | 20 (17/3) |

| Distortion of Wirsung’s duct | 16 |

| Stenosis or compression of Wirsung’s duct | 6 |

| Other | 2 |

| Diagnostic ERCP | 26 |

| Indications | |

| Cystic neoplasm (IPMN/ MCN/ SCN) | 7 (5/1/1) |

| AIP | 5 |

| Pancreas divisum | 4 |

| RAP | 5 |

| Pancreatic mass | 3 |

| Others | 2 |

| Pancreatic juice cytology (with ENPD/ with POPS) | 11 (4/ 2) |

| Therapeutic ERCP | 18 |

| CP | 8 |

| RAP | 5 |

| Pancreatic pseudocyst | 4 |

| Pancreatic trauma | 1 |

| Minor papillotomy | 17 |

| Needle-knife | 13 |

| Pull-type papillotome | 4 |

Minor papilla cannulation was successful in 35 of 44 ERCPs (80%). After we included WGC in the minor papilla approach in April 2009, the success rate of cannulation showed significant improvement (conventional contrast cannulation vs WGC = 50% vs 86%, P = 0.04) (Table 2). Application of WGC to the minor papilla may be useful as well as biliary cannulation.

| Success | Failure | Total | Success rate | P value | |

| Before April 2009 (CC) | 4 | 4 | 8 | 50% | 0.04 |

| After April 2009 (WGC) | 31 | 5 | 36 | 86% | 0.04 |

| Total | 35 | 9 | 44 | 80% |

The clinical profiles of the 13 patients who underwent 18 sessions of therapeutic ERCP are summarized in Table 3. Therapeutic procedures were completed in 16 of 18 cases (89%). Of the 16 therapeutic ERCP cases with completed treatment procedures, 11 underwent minor papillotomy with placement of an EPS or ENPD tube. One case received balloon dilation of the minor papilla following a minor papillotomy, and 4 cases underwent exchange or removal of an EPS. In 1 case, it was difficult to perform the endoscopic treatment due to a MPD injury resulting from pancreatic trauma because a guidewire could not be advanced to the pancreatic tail.

| Patients | Age/sex | Session | Disease | Causes of difficult access through the major papilla | Intervention | Technical success/failure | Short-term outcome | Complication |

| 1 | 13/F | 1 | Trauma | MPD injury | Failure | NA | None | |

| 2 | 62/M | 2 | Pseudocyst | Compression of WD | EMP + ENPD | Success | Appropriate drainage | None |

| 3 | Pseudocyst | Compression of WD | Exchange of EPS | Success | Appropriate drainage | None | ||

| 4 | Pseudocyst | Compression of WD | Removal of EPS | Success | Collapse of pseudocyst | None | ||

| 3 | 69/M | 5 | CP | Distortion of WD | EMP + EPS | Success | Pain relief | None |

| 4 | 36/M | 6 | CP | Distortion of WD | EMP + EPS | Success | Pain relief | None |

| 5 | 69/M | 7 | CP | Divisum | EMP + EPS | Success | Pain relief | None |

| 8 | CP | Divisum | Balloon dilation | Success | Pain relief | None | ||

| 6 | 64/M | 9 | Pseudocyst | Compression of WD | EMP + ENPD | Success | Ineffective1 | None |

| 7 | 40/M | 10 | RAP | Stenosis of WD | EMP + EPS | Success | Appropriate drainage | PEP |

| 11 | RAP | Stenosis of WD | Exchange of EPS | Success | No recurrence | None | ||

| 8 | 36/M | 12 | RAP | Divisum | EMP + ENPD | Success | Appropriate drainage | None |

| 13 | RAP | Divisum | Exchange of EPS | Success | No recurrence | None | ||

| 9 | 62/M | 14 | CP | Divisum | EMP + EPS | Success | Pain relief | None |

| 10 | 74/M | 15 | CP | Divisum | EMP + EPS | Success | Pain relief | None |

| 11 | 42/M | 16 | CP | Distortion of WD | Failure | NA | None | |

| 12 | 68/F | 17 | CP | Distortion of WD | EMP + EPS | Success | Pain relief | None |

| 13 | 68/M | 18 | RAP | Distortion of WD | EMP + EPS | Success | No recurrence | None |

Of the 16 cases in which therapeutic procedures were completed, 15 (94%) achieved short-term improvement, i.e., pain relief in patients with CP, no recurrence in patients with RAP, or effective drainage in patients with pseudocyst. In 1 case of pancreatic pseudocyst, although an ENPD tube was successfully inserted into the pseudocyst through the minor papilla, the infection was not controlled. He underwent a surgical procedure (pseudocyst-jejunostomy), which resulted in immediate improvement. As a result, clinical improvement was achieved in 83% (15/18) of all therapeutic ERCP sessions.

There were no complications, such as bleeding or perforation, related to minor papillotomy or balloon dilation. However, 2 cases (4.5%) developed mild PEP. One case was a diagnostic ERCP for AIP and only a diagnostic pancreatogram was performed. The other was a therapeutic ERCP for a patient with RAP who underwent a minor papillotomy plus pancreatic stent placement through the minor papilla. In both cases, cannulation and contrast injection were attempted through the major papilla prior to the minor papilla approach. Conservative treatment promptly resolved PEP in both cases. No other complications, including problems in stent placement (migration or occlusion), occurred in the present study.

Endoscopic diagnosis or treatment of pancreatic diseases is usually performed through the major papilla. However, the major papilla approach is sometimes difficult for patients with pancreas divisum or distortion of the MPD. In those patients, an approach through the minor papilla is attempted as the only alternative for the management of pancreatic diseases, although minor papilla cannulation remains challenging even for experienced endoscopists. Inui et al[12] reported that an endoscopic approach through the minor papilla requires superior endoscopic skills, and the number of patients who require these procedures is relatively small, which should limit the use of this approach to select institutions with appropriate expertise. In this study, we reviewed patients who underwent procedures using an endoscopic minor papilla approach at our institution, evaluated the content, safety and outcome of this procedure.

In this study, minor papilla cannulation was successful in 35 of 44 ERCPs (80%). This result is lower than previously reported, as shown in Table 4.

| Ref. | No. of patients | Disease | Divisum | Cannulation method | Cannulation success | Intervention | Improvement | PEP |

| Borak et al[2] | 113 | RAP | 100% | NA | NA | EMP + EPS | 62% | 10.60% |

| Maple et al[3] | 64 | RAP | 100% | Endoscopists’ preference | 85 | EMP + EPS | NA | 14% |

| Chacko et al[4] | 57 | RAP/CP | 100% | Tapered catheter and guidewire | 86 | EMP + EPS | 58% | 10.70% |

| Attwell et al[5] | 184 | CP | 100% | Tapered catheter | NA | EMP + EPS | 72% | 6.50% |

| Song et al[9] | 11 | CP | 0% | Rendezvous technique or CC | 91 | EMP + ENPD, ESWL | 91% | 0% |

| Heyries et al[6] | 24 | RAP | 100% | Tapered catheter and guidewire | NA | EMP 8, EMP + EPS 16 | 92% | 12.50% |

| Maple et al[11] | 25 | RAP | 88% | Physician-controlled WGC | 96 | EMP + EPS | NA | 12% |

| Gerke et al[15] | 53 | RAP | 100% | NA | NA | EMP | 60.40% | 11.20% |

| Ertan et al[16] | 25 | RAP | 100% | Tapered catheter and guidewire | 74 | Dilation | 76% | 0% |

| Boerma et al[17] | 16 | CP | 100% | NA | NA | EPS with/without EMP | 69% | 6.30% |

| This study | 34 | RAP/CP | 45% | WGC or CC | 80 | EMP + EPS | 83% | 4.50% |

However, the cannulation success rate improved after we employed a WGC technique (50% to 86%). Wire-guided biliary cannulation has recently attracted attention, and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCT) have demonstrated a higher cannulation success and lower PEP when a wire-guided technique is used, than with conventional contrast methods[13,14]. However, the number of studies on the application of WGC to the minor papilla is very limited. Maple et al[11] reported that physician-controlled WGC in the minor papilla approach is an effective and safe technique. In agreement with the previous study, WGC or wire-assisted cannulation in the minor papilla approach improved the success rate. Although skill development due to the high number of patients may be another reason for the cannulation success rate improvement, application of WGC to the minor papilla approach may be useful as well as biliary cannulation. Maple et al[11] also stated that a highly experienced assistant was required for wire management. At our institution, 2 experienced endoscopists usually perform this procedure; 1 handles the endoscope while the other assists with the guidewire. We believe that insertion of the guidewire into Santorini’s duct is the most important step during the procedure, and it requires close corporation between the endoscopist manipulating the catheter and the assistant advancing the guidewire[12].

A summary of this study and recently published data on the minor papilla approach is shown in Table 4[2-6,9,11,15-17]. Most patients had pancreas divisum, which is the most common anatomical variation affecting the pancreatic ductal system[1]. Although most patients with pancreas divisum demonstrate no symptoms, relative outflow obstruction of the minor papilla and increased ductal pressure may result in pancreatitis, such as CP and RAP, which require surgical or endoscopic treatment[2]. Many studies have demonstrated the benefit of minor papillotomy for patients with pancreas divisum and RAP, with response rates as high as 90%[6,18,19]. In this study, 4 patients with pancreas divisum underwent minor papillotomy as a therapeutic option (Table 3) and all of them clinically responded, that is, they experienced pain relief or no recurrence of AP. Although we only obtained short-term outcomes, clinical improvement was achieved in 83% of all therapeutic procedures, which is nearly equal to that in previous studies, as shown in Table 4. Endoscopic intervention through the minor papilla can be an effective therapeutic option when it is difficult to access the MPD through the major papilla.

Several previous studies of endoscopic intervention through the minor papilla have reported an early complication rate with PEP of 10% to 14%[2-4,6,11,15]. Another report by Moffatt revealed that patients with pancreas divisum undergoing minor papilla cannulation with or without minor papillotomy should be considered at high risk for PEP (10.2% with papillotomy and 8.2% without)[20]. Therefore, endoscopic minor papilla intervention is regarded as somewhat more hazardous than typical ERCP techniques[5]. Minor papillotomy is usually performed using either a needle-knife or pull-type sphincterotome, however, which of these techniques is better remains uncertain. Attwell et al[5] reported that both techniques are equally safe and effective. At our institution, the needle-knife technique is used more often because the orifice of the minor papilla is usually too small to allow a pull-type sphincterotome to advance too deeply. We performed minor papillotomy with both techniques being careful not to cut too much, and the incision range was usually determined within the orifice of the minor papilla. Therefore, no major complications directly related to the incision such as bleeding and perforation were encountered. On the other hand, early complications with PEP occurred in 4.5% (2/44) of procedures in the present study. Both cases with PEP underwent major papilla cannulation and contrast injection prior to the minor papilla approach. In 1 case, a diagnostic ERCP was performed for AIP, and an EPS was not inserted through the minor papilla after ERCP. In the other case, a therapeutic ERCP was performed for RAP with minor papillotomy and EPS placement through the minor papilla. His pancreatogram revealed stenosis of Wirsung’s duct; therefore, the PEP may be related to the major papilla cannulation and contrast injection. Major papilla cannulation in these cases is inevitable because unanticipated findings of pancreas divisum or distortion of Wirsung’s duct may be revealed during ERCP; however, the procedure should be performed with greater caution. We should also consider prophylactic pancreatic stent placement through the minor papilla, even in diagnostic ERCP, for the prevention of PEP[8,21]. No other complications, such as bleeding or perforation, were observed in this study. Although this study was small compared to previous studies, the results were favorable. We believe that the endoscopic minor papilla approach is technically feasible and safe when performed in a high-volume referral center by experienced endoscopists.

This study confirmed the feasibility, benefit of WGC, and safety of endoscopic intervention through the minor papilla for the management of pancreatic diseases. However, a number of limitations must be considered while evaluating the results of this study. For example, these data were obtained in a retrospective study, not a comparative study. We only described a single-center experience; therefore, the number of patients was small, and may be inadequate to compare the therapeutic effects with different procedures for various pancreatic diseases. However, it is difficult to design a large-scale RCT due to the relatively small number of patients requiring a minor papilla approach. Nonetheless, further large-scale studies are required to definitively assess the efficacy of endoscopic interventions through the minor papilla in the management of pancreatic diseases.

When an endoscopic approach through the major papilla is difficult because of pancreas divisum, distortion of Wirsung’s duct, or other causes, the minor papilla approach is attempted as the alternative for the management of pancreatic diseases. However, the efficacy and safety of this procedure is not fully understood.

Minor papilla cannulation is challenging even for experienced endoscopists. Several previous studies revealed the success rate of minor papilla cannulation as approximately 70%-90%. Although the usefulness of wire-guided cannulation (WGC) for biliary tract has been reported, the number of studies on the application of WGC to the minor papilla is very limited. From the point of view of the endoscopic treatment through the minor papilla, several studies have demonstrated the benefit of minor papillotomy or endoscopic pancreatic stent placement in patients with pancreas divisum. However, endoscopic minor papilla intervention is regarded as somewhat more hazardous than typical endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) techniques because of the high rates of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP).

In this study, the most common cause for difficult access to the main pancreatic duct through the major papilla was pancreas divisum followed by distortion of Wirsung’s duct. The overall success rate of minor papilla cannulation was 80%, which showed significant improvement with WGC. Endoscopic minor papillotomy with pancreatic stent placement, which was the main therapeutic option for patients with chronic pancreatitis, recurrent acute pancreatitis, and pancreatic pseudocyst, resulted in short-term clinical improvement in 83% of patients. Mild PEP occurred as an early complication in 2 cases (4.5%). The authors could obtain the feasible results of clinical improvement and complications compared to previous studies.

Application of WGC to the minor papilla approach may be as useful in biliary cannulation as well. The best candidates for endoscopic interventions through the minor papilla are patients with symptomatic pancreas divisum. The endoscopic minor papilla approach is technically feasible, safe and effective when the procedure is performed in a high-volume referral center by experienced endoscopists.

This is a nicely written paper on an old subject; the discussion underlines old controversies on pancreas divisum source of chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic pain. WGC is a promising method for minor papilla cannulation.

P- Reviewers Chow WK, Rey JF S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Kamisawa T. Endoscopic approach to the minor duodenal papilla: special emphasis on endoscopic management on pancreas divisum. Dig Endosc. 2006;18:252-255. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Borak GD, Romagnuolo J, Alsolaiman M, Holt EW, Cotton PB. Long-term clinical outcomes after endoscopic minor papilla therapy in symptomatic patients with pancreas divisum. Pancreas. 2009;38:903-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Maple JT, Keswani RN, Edmundowicz SA, Jonnalagadda S, Azar RR. Wire-assisted access sphincterotomy of the minor papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:47-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chacko LN, Chen YK, Shah RJ. Clinical outcomes and nonendoscopic interventions after minor papilla endotherapy in patients with symptomatic pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:667-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Attwell A, Borak G, Hawes R, Cotton P, Romagnuolo J. Endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy for pancreas divisum by using a needle-knife or standard pull-type technique: safety and reintervention rates. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:705-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Heyries L, Barthet M, Delvasto C, Zamora C, Bernard JP, Sahel J. Long-term results of endoscopic management of pancreas divisum with recurrent acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:376-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2036] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Sofuni A, Maguchi H, Mukai T, Kawakami H, Irisawa A, Kubota K, Okaniwa S, Kikuyama M, Kutsumi H, Hanada K. Endoscopic pancreatic duct stents reduce the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in high-risk patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:851-88; quiz e110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Song MH, Kim MH, Lee SK, Lee SS, Han J, Seo DW, Min YI, Lee DK. Endoscopic minor papilla interventions in patients without pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:901-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Maple JT, Mansour L, Ammar T, Ansstas M, Coté GA, Azar RR. Physician-controlled wire-guided cannulation of the minor papilla. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2010;2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Inui K, Yoshino J, Miyoshi H. Endoscopic approach via the minor duodenal papilla. Dig Surg. 2010;27:153-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Ceroni L, Laterza L, Fabbri C, Bazzoli F. Can a wire-guided cannulation technique increase bile duct cannulation rate and prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis?: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2343-2350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cheung J, Tsoi KK, Quan WL, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Guidewire versus conventional contrast cannulation of the common bile duct for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1211-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gerke H, Byrne MF, Stiffler HL, Obando JV, Mitchell RM, Jowell PS, Branch MS, Baillie J. Outcome of endoscopic minor papillotomy in patients with symptomatic pancreas divisum. JOP. 2004;5:122-131. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Ertan A. Long-term results after endoscopic pancreatic stent placement without pancreatic papillotomy in acute recurrent pancreatitis due to pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Boerma D, Huibregtse K, Gulik TM, Rauws EA, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Long-term outcome of endoscopic stent placement for chronic pancreatitis associated with pancreas divisum. Endoscopy. 2000;32:452-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lans JI, Geenen JE, Johanson JF, Hogan WJ. Endoscopic therapy in patients with pancreas divisum and acute pancreatitis: a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:430-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fukumori D, Ogata K, Ryu S, Maeshiro K, Ikeda S. An endoscopic sphincterotomy of the minor papilla in the management of symptomatic pancreas divisum. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:561-563. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Moffatt DC, Coté GA, Avula H, Watkins JL, McHenry L, Sherman S, Lehman GA, Fogel EL. Risk factors for ERCP-related complications in patients with pancreas divisum: a retrospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:963-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mazaki T, Masuda H, Takayama T. Prophylactic pancreatic stent placement and post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2010;42:842-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |