Published online Mar 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i3.111

Revised: August 14, 2012

Accepted: January 23, 2013

Published online: March 16, 2013

AIM: To investigate the feasibility of double-balloon endoscopy (DBE) to detect jejunoileal lymphoma, compared with fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET).

METHODS: Between March 2004 and January 2011, we histologically confirmed involvement of malignant lymphoma of the jejunoileum in 31 patients by DBE and biopsy. In 20 patients of them, we performed with FDG-PET. We retrospectively reviewed the records of these 20 patients. Their median age was 64 years (range 50-81). In the 20 patients, the pathological diagnosis of underlying non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) comprised follicular lymphoma (FL, n = 12), diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL, n = 4), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL, n = 2), enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma (ETL, n = 1) and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL, n = 1).

RESULTS: Ten cases showed accumulation by FDG-PET (50%). FDG-PET was positive in 3 of 12 FL cases (25%) while in 7 of 8 non-FL cases (88%, P < 0.05). Intestinal FL showed a significantly lower rate of positive FDG-PET, in comparison with other types of lymphoma. Cases with endoscopically elevated lesions (n = 10) showed positive FDG-PET in 2 (20%), but those with other type NHL did in 8 of 10 (80%, P < 0.05). When the cases having elevated type was compared with those not having elevated type lesion, the number of cases that showed accumulation of FDG was significantly smaller in the former than in the latter.

CONCLUSION: In a significant proportion, small intestinal involvement cannot be pointed out by FDG-PET. Especially, FL is difficult to evaluate by FDG-PET but essentially requires DBE.

- Citation: Ibuka T, Araki H, Sugiyama T, Nakanishi T, Onogi F, Shimizu M, Hara T, Takami T, Tsurumi H, Moriwaki H. Diagnosis of the jejunoileal lymphoma by double-balloon endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(3): 111-116

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i3/111.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i3.111

The clinical stage of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is usually determined by imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). FDG-PET has become a routine measure for staging and follow-up of patients with malignant lymphoma[1]. Staging parameters include extranodal involvement, and the gastrointestinal tract is the most common site. Although the actual incidence of small intestinal involvement is unknown, surgical pathology estimates that small intestinal lymphoma accounts for 4%-12% of all reported NHL[2-4]. Since small intestinal involvement of NHL easily leads to perforation, peritonitis, and subsequent poor outcome after chemotherapy, investigations into the small intestine are important to determine the most appropriate treatment strategy for patients with NHL. However, there is a limitation in the diagnosis by FDG-PET for this aim, since biologic characteristics of specific histologic subtypes of lymphoma result in different degrees of FDG uptake[5]. Capsule endoscopy or double-balloon endoscopy (DBE) can detect such lesions of lymphoma, but biopsy samples can be obtained only by using DBE. DBE is a novel diagnostic and therapeutic modality that was originally described by Yamamoto et al[6]. The procedure allows high-resolution images, as well as diagnostic sampling and therapeutic interventions in all segments of the small intestine. Thus, DBE developed non-surgical evaluation of the small intestine. Here, we examined the feasibility of DBE to detect small intestinal involvement of NHL, in comparison with FDG-PET.

Between March 2004 and January 2011, we histologically confirmed involvement of malignant lymphoma of the jejunoileum in 31 patients by DBE and biopsy. In 20 patients of them, we performed with FDG-PET. We retrospectively reviewed the records of these 20 patients. Their median age was 64 years (range 50-81 years). Their demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. In the 20 patients, the pathological diagnosis of underlying NHL comprised follicular lymphoma (FL, n = 12), diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL, n = 4), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL, n = 2), enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma (ETL, n = 1) and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL, n = 1) (Table 2).

| Total number of patients | 20 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 |

| Female | 6 |

| Median age (yr) | 64 |

| (range) | (50-81) |

| Observation | |

| Jejunum + ileum | 11 |

| Jejunum | 4 |

| Ileum | 5 |

| Location | |

| Jejunum + ileum | 9 |

| Jejunum | 6 |

| Ileum | 5 |

| Number of lesions | |

| Solitary | 2 |

| Multiple | 16 |

| Diffuse | 2 |

| FDG-PET | P value | |||

| All cases | Positive | Negative | ||

| All cases | 20 | 10 | 10 | |

| Histology | ||||

| FL | 12 | 3 | 9 | |

| DLBCL | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| MCL | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| ETL | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| ALCL | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| FL | 12 | 3 | 9 | < 0.051 |

| Others | 8 | 7 | 1 | |

| Endoscopic findings | ||||

| Elevated | 5 | 1 | 4 | |

| Ulcerative | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| MLP | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Diffuse infiltration | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Diffuse infiltration + ulcerative | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Elevated + MLP | 5 | 1 | 4 | |

| Including elevated | 10 | 2 | 8 | < 0.051 |

| Not including elevated | 10 | 8 | 2 | |

| Clinical Stage | ||||

| I | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| II | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| III | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| IV | 9 | 5 | 5 | |

| I/II | 6 | 4 | 3 | NS |

| III/IV | 12 | 6 | 7 | |

| Abdominal symptom | ||||

| Present | 6 | 5 | 1 | NS |

| Absent | 14 | 5 | 9 | |

| B symptom | ||||

| Present | 10 | 5 | 5 | NS |

| Absent | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| Other gastrointestinaltract lesions | ||||

| Absent | 10 | 6 | 4 | NS |

| Present | 10 | 4 | 6 | |

| Esophagus | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Stomach | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Duodenum | 12 | 5 | 7 | |

| Colon | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| PS | ||||

| 0 | 18 | 9 | 9 | NS |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||

| Median | 13.7 | 13.1 | 14.1 | NS |

| (range) | (7.8-17.1) | (7.8-16.3) | (12.1-17.1) | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (IU/L) | ||||

| Median | 196 | 197 | 187 | NS |

| (range) | (108-1195) | (108-342) | (126-1195) | |

| Soluble interleukin-2 receptor (U/mL) | ||||

| Median | 1350 | 2302 | 802 | NS |

| (range) | (363-7410) | (371-6880) | (363-7410) | |

Eligibility criteria for DBE in lymphoma patients were: (1) lymphoma infiltration of the stomach, duodenum or colon proven by gastrointestinal endoscopy or colonoscopy which are routine evaluation of lymphoma patients in our institution; (2) intraabdominal lesion suspected from CT or gallium-scintigraphy/FDG-PET imaging; or (3) any gastrointestinal symptoms such as a bloated sensation in the abdomen, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, protein-losing syndrome or hematochezia. Exclusion criterion was poor performance status of grade 3 or 4 assessed by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group classification[7]. We conducted DBE from both oral and anal routes in principle. However, in the patients who did not give consent to this dual approach mainly due to the examination burden, we selected only one-sided insertion according to the information of preceding gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy.

We observed jejunum and ileum in 11 cases by the combination of both oral and anal approach, only jejunum in 4 cases by oral approach, and only ileum in 5 cases by anal approach. Six, five and nine patients had lesions in the jejunum, ileum, and in both, respectively. We observed multiple lesions in 16 cases, solitary lesion in 2 cases, and diffuse lesion in 2 cases.

DBE was carried out in the Endoscopy Unit of Gifu University Hospital using a Fujinon system (EN450-T5/W, Fujinon Corporation, Saitama, Japan). The whole procedure is similar to that described in detail elsewhere[8-10]. In brief, the system comprises an endoscope and a flexible overtube that are both provided with soft latex balloons connected through a built-in air route to a controlled pump system. Patients ingested 2 L of a polyethylene glycol-based solution on the day before the examination. The small intestine was examined endoscopically using a combination of anterograde (oral) and retrograde (anal) DBEs. We obtained biopsy specimens of all lesions detected during the procedure.

Pretreatment characteristics were compared between FDG-PET-positive and -negative patients by the Fisher’s exact test or Student’s t-test. P values of < 0.05 indicated significance.

Ten of 20 cases with malignant lymphoma confirmed by DBE showed accumulation by FDG-PET (50%). In these 10 cases, histopathological classification was FL in 3 cases, DLBCL in 3, MCL in 2, ETL in 1 and ALCL in 1. In the cases which did not show FDG accumulation, histopathological classification was FL in 9 cases and DLBCL in 1. Thus, intestinal FL showed a significantly lower rate of positive FDG-PET, in comparison with other types of lymphoma (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Macroscopically, 5 tumors were classified as elevated type (5 FL cases), 5 as ulcerative type (4 DLBCL cases, 1 FL case), 3 as multiple lymphomatoid polyposis (MLP) type (2 MCL cases, 1 FL case), 1 as diffuse-infiltrating type (1 ETL case), 1 as diffuse infiltration+ulcerative (1 ALCL case) and 5 as elevated + MLP type (5 FL cases). Thus, the cases with elevated type all belonged to FL.

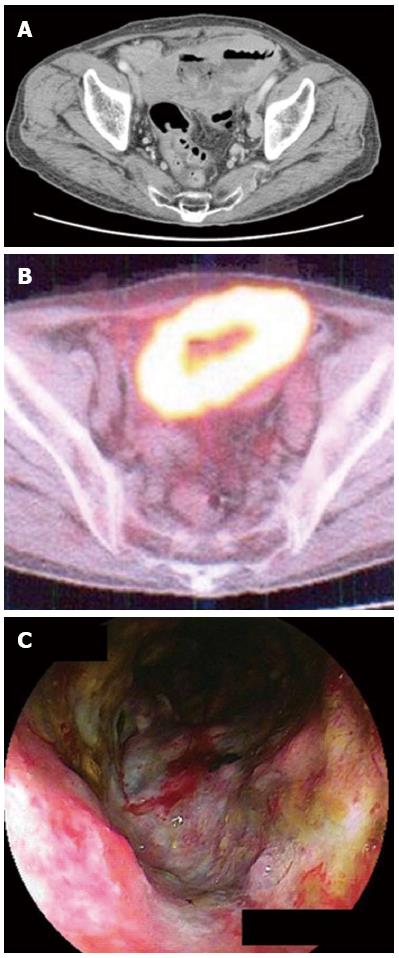

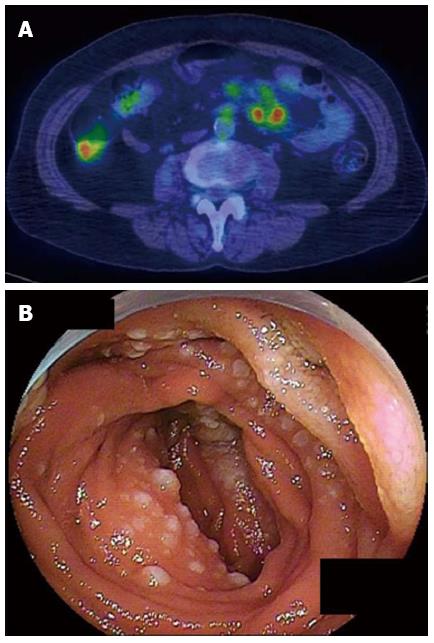

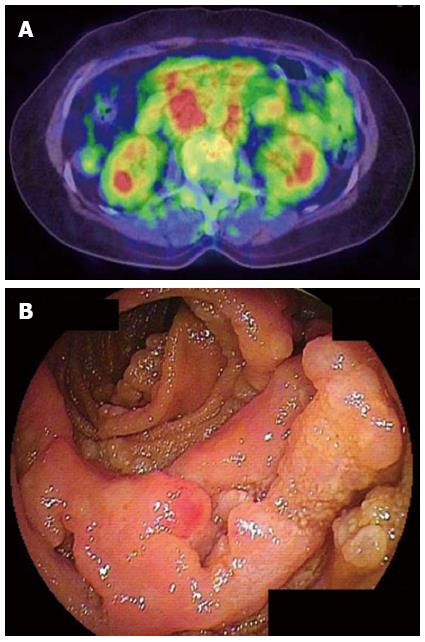

In the 10 cases that showed accumulation of FDG, 4 tumor was classified as ulcerative type (Figure 1), 2 as MLP type, 1 as elevated type (Figure 2), 1 as diffuse-infiltrating type, 1 as diffuse infiltration+ulcerative and 1 as elevated + MLP type. In other 10 cases that did not show accumulation of FDG, 4 tumors were classified as elevated type (Figure 3), 1 as ulcerative type, 1 as MLP type, and 4 as elevated + MLP type. When the cases having elevated type was compared with those not having elevated type lesion, the number of cases that showed accumulation of FDG was significantly smaller in the former than in the latter (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Clinical stage, abdominal symptom, B symptom, other gastrointestinal tract lesions, performance status (PS), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), hemoglobin (Hb) or soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) did not produce significant difference in the accumulation of FDG (Table 2).

We had no complications associated with DBE in all twenty cases.

NHL frequently involves the gastrointestinal tract and forms multiple tumors[11-14]. Since the small intestine is a preferential site of such involvement[2-4] and could be complicated with perforation following chemotherapy, it is important to diagnose NHL invasion into the small intestine in advance. For this aim, DBE is invasive while FDG-PET is not. Thus, FDG-PET is now a routine measure for staging and follow-up of patients with malignant lymphoma[1], since it has been proven as useful to clinically evaluate these patients[15]. In our study, however, FDG-PET could not detect small intestinal involvement in 10 (50%) of the 20 patients with confirmed small intestinal involvement. Therefore, we emphasize that DBE is essential for the diagnosis of such involvement of lymphoma and for the subsequent management of the patients. Less invasive capsule endoscopy can image the entire gastrointestinal tract and thus might also be useful to detect small intestinal involvement of lymphoma[16,17]. However, application of this method is limited, because biopsy specimens cannot be obtained. Although invasive, DBE is the sole endoscopic approach that enables biopsy of small intestine.

The good diagnostic ability of FDG-PET for extranodal lymphoma lesions has been demonstrated with sensitivity of 67%-100%[18-22]. Our sensitivity of FDG-PET was lower than previous reports, probably because the number of FL cases was large.

Yamamoto et al[23] reported that in 14 of 16 FL cases of the small intestine, there were no obvious accumulations of 18F-FDG in the primary lesions, giving a low diagnostic sensitivity of 12.5%. In our study, the proportion of patients with positive FDG-PET was significantly lower in FL cases when compared to other types of lymphoma (Table 2). On the other hand, it is reported that FDG-PET detected disease on at least one site in 98% of FL patients[5], supporting its usefulness for staging of patients with FL[24]. However, in another report of duodenal FL, 18F-FDG accumulated in the mesenteric lymph nodes but not in the primary duodenal site[25]. Hoffmann et al[26] also reported that FDG-PET is not useful for clinical assessment of primary duodenal FL. Higuchi et al[27] further reported that increased uptake of 18F-FDG was not observed in the confirmed jejunoileal FL lesions in their 6 patients. We also experienced FL case that 18F-FDG accumulated in the intraabdominal lymph nodes, whereas there was no obvious uptake in the jejunoileum site (Figure 3). We thus think that FDG-PET is not useful for clinical assessment of jejunoileum FL and DBE is essential to diagnose the gastrointestinal involvement of FL. Thus, as reported by Tanaka et al[28], intestinal FL seems to have distinct clinicopatholigical characteristics from other intestinal lymphoma.

The morphological features of small intestinal involvement were basically the same as those in the stomach or duodenum[11-14]. We identified a variety of morphologies, such as ulcerative, MLP, diffuse infiltration, and elevated types. The most typical finding in FL was multiple whitish small nodules. Nakamura et al[29] showed that endoscopic findings of primary intestinal FL by DBE were varied, including mass formation, swelling of folds, and stenosis of intestine. In our analysis, multiple whitish small nodules, mass formation and swelling of folds were included in elevated type.

In the cases including elevated type, accumulation of FDG appeared in significantly fewer cases than in those without elevated type (Table 2). For the reason, we suppose that majority of FL patients showed elevated type of small intestinal involvement.

Although we had no complications associated with DBE in all twenty cases, it is reported that 40 adverse events were experienced in 2362 DBE procedure (1.7%)[30], including pancreatitis in 7 patients (0.3%), bleeding in 19 patients (0.8%), perforation in 6 patients (0.3%), and others in 8 (0.3%). However, only regarding diagnostic DBE (1728 patients), the incidence of complication was 0.8%[30]. We think that DBE is a safe and well-tolerated method, but it is necessary to take care about adverse events.

In conclusion, in a significant proportion of lymphoma cases, small intestinal involvement cannot be pointed out by FDG-PET. Especially, the small intestinal FL is difficult to evaluate by FDG-PET but essentially requires DBE.

Presence of small intestinal involvement is important to determine the clinical stage and subsequent most appropriate treatment strategy in patients with malignant lymphoma. However, there is a limitation in the currently recommended diagnostic modality of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). Here, the authors examined the feasibility of double-balloon endoscopy (DBE) to detect small intestinal involvement of lymphoma, in comparison with FDG-PET.

The good diagnostic ability of FDG-PET for extranodal lymphoma lesions has been generally agreed. However, the diagnostic power of FDG-PET is significantly low for primary duodenal follicular lymphoma.

Many papers report the usefulness of FDG-PET to detect the small intestinal involvement of lymphoma, but limitation also exists as described above. The authors examined the feasibility of DBE to detect small intestinal involvement of lymphoma in comparison with FDG-PET and broke-through that limitation.

In a significant proportion of lymphoma cases, small intestinal involvement cannot be pointed out by FDG-PET. Especially, the small intestinal follicular lymphoma is difficult to evaluate by FDG-PET but essentially requires DBE.

DBE is an innovative fiber endoscopy equipped with double balloon function that enables observation and biopsy of deep small intestine. DBE actually covers the whole small intestine when used with both oral and anal insertion routes. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) shares about 95% of malignant lymphoma in Japan. Major subtypes of NHL include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma.

In this article, the authors described the better diagnostic yield of using DBE than using PET scan in the diagnosis of small bowel follicular lymphoma. The results are interesting and potentially clinically meaningful.

P- Reviewers Yan SL, Girelli CM S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Kumar R, Maillard I, Schuster SJ, Alavi A. Utility of fluorodeoxyglucose-PET imaging in the management of patients with Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:1083-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rosenberg SA, Diamond HD, Jaslowitz B, Craver LF. Lymphosarcoma: a review of 1269 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1961;40:31-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 749] [Cited by in RCA: 657] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer. 1972;29:252-260. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bush RS. Primary lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract. JAMA. 1974;228:1291-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Elstrom R, Guan L, Baker G, Nakhoda K, Vergilio JA, Zhuang H, Pitsilos S, Bagg A, Downs L, Mehrotra A. Utility of FDG-PET scanning in lymphoma by WHO classification. Blood. 2003;101:3875-3876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, Ido K, Sugano K. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 861] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7038] [Cited by in RCA: 7981] [Article Influence: 190.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | May A, Nachbar L, Wardak A, Yamamoto H, Ell C. Double-balloon enteroscopy: preliminary experience in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding or chronic abdominal pain. Endoscopy. 2003;35:985-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamamoto H, Kita H, Sunada K, Hayashi Y, Sato H, Yano T, Iwamoto M, Sekine Y, Miyata T, Kuno A. Clinical outcomes of double-balloon endoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of small-intestinal diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1010-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yamamoto H, Kita H. Double-balloon endoscopy. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yoshino T, Miyake K, Ichimura K, Mannami T, Ohara N, Hamazaki S, Akagi T. Increased incidence of follicular lymphoma in the duodenum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:688-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shia J, Teruya-Feldstein J, Pan D, Hegde A, Klimstra DS, Chaganti RS, Qin J, Portlock CS, Filippa DA. Primary follicular lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinical and pathologic study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:216-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Damaj G, Verkarre V, Delmer A, Solal-Celigny P, Yakoub-Agha I, Cellier C, Maurschhauser F, Bouabdallah R, Leblond V, Lefrère F. Primary follicular lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a study of 25 cases and a literature review. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:623-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma in Japan: a clinicopathologic analysis of 455 patients with special reference to its time trends. Cancer. 2003;97:2462-2473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schöder H, Meta J, Yap C, Ariannejad M, Rao J, Phelps ME, Valk PE, Sayre J, Czernin J. Effect of whole-body (18)F-FDG PET imaging on clinical staging and management of patients with malignant lymphoma. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1139-1143. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1994] [Cited by in RCA: 1383] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Flieger D, Keller R, May A, Ell C, Fischbach W. Capsule endoscopy in gastrointestinal lymphomas. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1174-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bangerter M, Moog F, Buchmann I, Kotzerke J, Griesshammer M, Hafner M, Elsner K, Frickhofen N, Reske SN, Bergmann L. Whole-body 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) for accurate staging of Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:1117-1122. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Jerusalem G, Warland V, Najjar F, Paulus P, Fassotte MF, Fillet G, Rigo P. Whole-body 18F-FDG PET for the evaluation of patients with Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Nucl Med Commun. 1999;20:13-20. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Buchmann I, Reinhardt M, Elsner K, Bunjes D, Altehoefer C, Finke J, Moser E, Glatting G, Kotzerke J, Guhlmann CA. 2-(fluorine-18)fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography in the detection and staging of malignant lymphoma. A bicenter trial. Cancer. 2001;91:889-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moog F, Bangerter M, Diederichs CG, Guhlmann A, Merkle E, Frickhofen N, Reske SN. Extranodal malignant lymphoma: detection with FDG PET versus CT. Radiology. 1998;206:475-481. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Sasaki M, Kuwabara Y, Koga H, Nakagawa M, Chen T, Kaneko K, Hayashi K, Nakamura K, Masuda K. Clinical impact of whole body FDG-PET on the staging and therapeutic decision making for malignant lymphoma. Ann Nucl Med. 2002;16:337-345. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Yamamoto S, Nakase H, Yamashita K, Matsuura M, Takada M, Kawanami C, Chiba T. Gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma: review of the literature. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:370-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Le Dortz L, De Guibert S, Bayat S, Devillers A, Houot R, Rolland Y, Cuggia M, Le Jeune F, Bahri H, Barge ML. Diagnostic and prognostic impact of 18F-FDG PET/CT in follicular lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:2307-2314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tanaka F, Tominaga K, Ochi M, Yamada T, Sasaki E, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Fujiwara Y, Uchida T, Oshitani N. Primary duodenal lymphoma: successful rituximab treatment and evaluation by FDG-PET. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1658-1661. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Hoffmann M, Chott A, Püspök A, Jäger U, Kletter K, Raderer M. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) does not visualize follicular lymphoma of the duodenum. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:276-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Higuchi N, Sumida Y, Nakamura K, Itaba S, Yoshinaga S, Mizutani T, Honda K, Taki K, Murao H, Ogino H. Impact of double-balloon endoscopy on the diagnosis of jejunoileal involvement in primary intestinal follicular lymphomas: a case series. Endoscopy. 2009;41:175-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Takata K, Okada H, Ohmiya N, Nakamura S, Kitadai Y, Tari A, Akamatsu T, Kawai H, Tanaka S, Araki H. Primary gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma involving the duodenal second portion is a distinct entity: a multicenter, retrospective analysis in Japan. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1532-1536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Umeno J, Yanai S, Shono Y, Suekane H, Hirahashi M, Yao T, Iida M. Endoscopic features of intestinal follicular lymphoma: the value of double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E26-E27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mensink PB, Haringsma J, Kucharzik T, Cellier C, Pérez-Cuadrado E, Mönkemüller K, Gasbarrini A, Kaffes AJ, Nakamura K, Yen HH. Complications of double balloon enteroscopy: a multicenter survey. Endoscopy. 2007;39:613-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |