INTRODUCTION

Carcinoids, also termed well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), are the most common neuroendocrine tumor of the gastrointestinal tract[1]. The incidence and prevalence of carcinoid tumors have increased quickly and steadily worldwide over the past few decades[2]. Rectal carcinoids are typically small, localized, nonfunctioning tumors that rarely metastasize[2]. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry database of the National Cancer Institute showed that the age-adjusted incidence of rectal carcinoids has increased from approximately 0.2 per 100000 in 1973 to 0.86 per 100000 in 2004[2,3]. The increased incidence can be partially explained by widespread colorectal cancer screening, heightened awareness, and improved diagnostic modalities. Rectal carcinoids comprise 12.6% of all carcinoid tumors and represent the third largest group of the gastrointestinal carcinoids in Western countries[1]. The frequency of rectal carcinoids is higher in studies from South Korea (48%) and Taiwan (25%) compared to Western countries[4,5]. The causes of racial/ethnic differences in NETs by site are unclear and require further investigation.

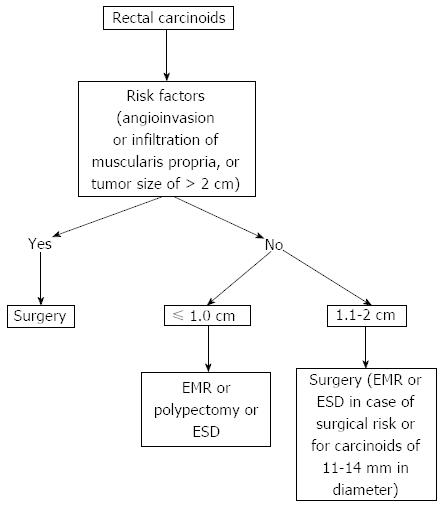

The treatment of rectal carcinoids depends on the tumor size (Figure 1). Recent consensus guidelines on the management of rectal carcinoids suggests that small tumors (< 1-2 cm) confined to the mucosa or submucosa can be managed with endoscopic resection due to their low risk of metastatic spread[6]. Rectal carcinoids estimated endoscopically as < 10 mm in diameter without atypical features and confined to the submucosal layer without lymphovascular invasion rarely metastasize. Therefore, these tumors are considered good candidates for local excision, including endoscopic resection. A variety of endoscopic techniques are used to treat rectal carcinoids. Those techniques include conventional polypectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), cap-assisted EMR (EMR-C or aspiration lumpectomy), endoscopic submucosal resection with ligating device (ESMR-L), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), and transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM). Due to a lack of controlled prospective studies, the management of small rectal carcinoid tumors has been a matter of debate. In this Technical Advances article, we review the efficacy and safety of various endoscopic treatments for small rectal carcinoid tumors.

Figure 1 Treatment of rectal carcinoids.

EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection.

CONVENTIONAL POLYPECTOMY OR EMR

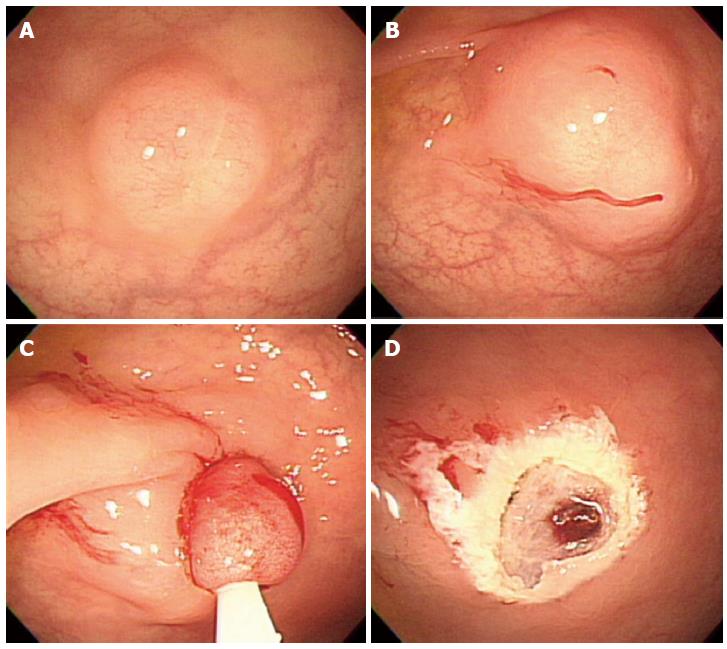

Endoscopic resection of rectal carcinoids with conventional polypectomy or EMR is a simple procedure (Figure 2)[7-9]. However, it is difficult to achieve histologically complete resection with these techniques because 76% of rectal carcinoids extend into the submucosal layer[9,10]. In addition, crush injury of resected specimens could lead to difficulty in pathologic evaluation[7]. The histologically complete resection rate of conventional polypectomy varies from 28.6% to 100% according to previous studies[11]. Incomplete resection of the tumors often requires additional surgical intervention.

Figure 2 Endoscopic mucosal resection.

A: An approximately 6 mm rectal carcinoid tumor; B: Injection of submucosal saline solution; C: Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) procedure; D: A clear, post-EMR ulcer.

POLYPECTOMY OR EMR USING TWO-CHANNEL COLONOSCOPY

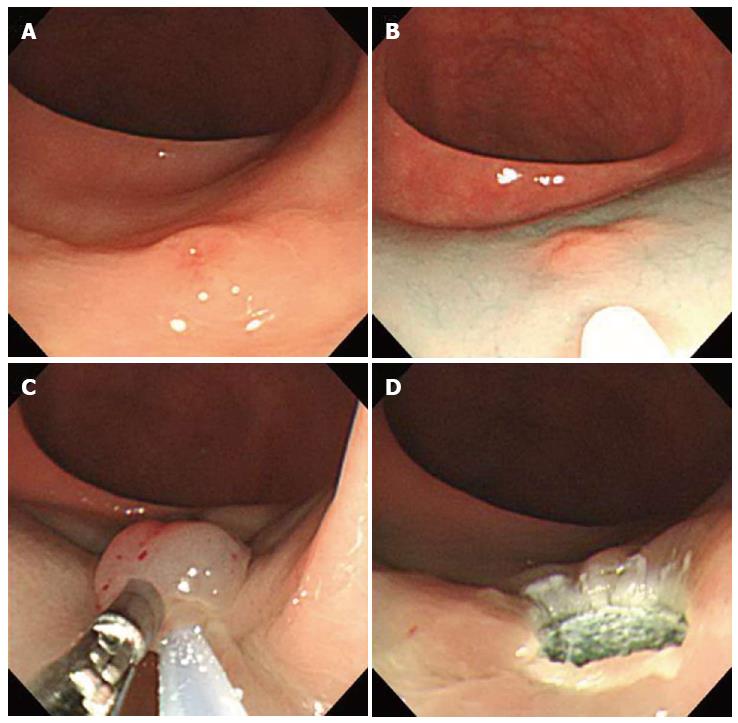

Using a two-channel colonoscope, both grasping forceps and a polypectomy snare can be inserted into the gastrointestina lumen simultaneously. Therefore, rectal carcinoids can be pulled toward the center of the lumen and resected by electrocoagulation (Figure 3). Iishi et al[12] demonstrated that the complete resection rate of rectal carcinoids with a two-channel colonoscopy (9 of 10 tumors, 90%) was significantly higher than with a one-channel colonoscopy (2 of 7 tumors, 29%). In addition, there were no complications during or after endoscopic treatment. Polypectomy or EMR using the two-channel method are expected to have a deeper vertical resection margin and lead to a curative resection. However, a recent study showed a positive resection margin in 11 (26%) of 58 EMR samples collected using the two-channel method. Furthermore, the complete resection rate of this method was not different from conventional EMR[13]. Another limitation is that the mucosa can be torn before the tumor is adequately elevated with the grasping forceps[14].

Figure 3 Endoscopic mucosal resection using two-channel colonoscopy.

A: An approximately 5 mm rectal carcinoid tumor; B: Injection of submucosal saline solution into the base of the lesion using needle forcep; C: Pulling the lesion with grasping forcep and snare resection; D: A clear, post-endoscopic mucosal resection ulcer.

EMR-C OR ASPIRATION LUMPECTOMY

Aspiration lumpectomy is an endoscopic approach for a tumor that can be easily resected by lifting the mucosa away from the submucosa with saline injection, followed by aspirating the lesion into a transparent cap or cylinder[15]. In 1996, Imada-Shirakat et al[16] reported that histologically complete resection was achieved in eight patients with rectal carcinoids less than 10 mm and located within the submucosal layer using this technique. There were no recurrences or distant metastasis found during the mean observation period of 13.3 mo. Nagai et al[14] demonstrated that the rate of complete resection with aspiration lumpectomy (100%) was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than with saline assisted snare resection (termed ‘strip biopsy’) in a small series of consecutive patients with rectal carcinoids. Jeon et al[17] used this technique for secondary endoscopic treatment to remove the remnant tumor after primary EMR or polypectomy, which is technically difficult due to submucosal fibrosis of residual tissue. This study demonstrated that EMR-C is a useful method for salvage treatment of a failed en bloc resection of rectal carcinoids after primary EMR or polypectomy. One of the interesting findings of this study is that all 7 patients had positive microscopic margins after primary EMR but negative endoscopic and histological findings based on a biopsy of the scarred tissue. The pathologic findings from all tissue obtained by salvage resection showed the existence of remnant tumor. This result suggests that a negative biopsy in a surveillance examination does not prove the absence of a remnant tumor and that false negative results might be due to embedding or the residual remnant tumor during tissue healing after the primary resection

ENDOSCOPIC SUBMUCOSAL RESECTION WITH LIGATING DEVICE

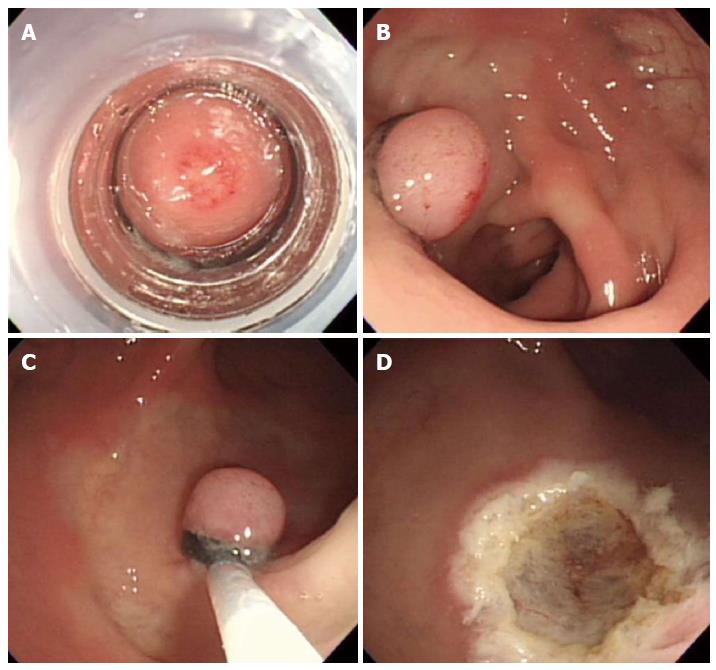

In 1999, Berkelhammer et al[18] first introduced the band-snare resection as a method of EMR for small rectal carcinods. This method may provide a more appropriate resection margin compared to standard polypectomy (Figure 4). A randomized controlled study comparing ESMR-L to EMR showed that the complete resection rate of ESMR-L (100%, 8/8) was significantly higher than EMR (57.1%, 4/7), and all patients were followed-up for 3 years without any recurrence[19]. In a large case series including 61 patients, the complete resection rate of ESMR-L was 95.2% (60 out of 63 lesions)[20]. The complete resection rate for lesions located in the lower rectum was 98.3%, which was significantly higher than lesions in the upper rectum and rectosigmoid colon (50%). In a large-scale study comparing ESMR-L (45 lesions) and EMR (55 lesions) including 100 cases, the overall ESMR-L complete resection rate was higher than EMR (93.3% vs 65.5%, respectively, P = 0.001)[21]. In addition, this study demonstrated that the location of the tumors had no influence on the complete resection rate when ESMR-L was performed, in contrast to the results of EMR. Recently, Moon et al[22] introduced EMR using a double ligation technique (ESMR-DL) to treat 11 patients with small rectal carcinoids. The lesion was aspirated into the ligating device, and an elastic band was placed around the base. Then, a detachable snare was used to perform a ligation below the elastic band, and the lesion was removed with snare resection above the band. After ESMR-DL, there were no immediate or delayed complications such as bleeding or perforation.

Figure 4 Endoscopic submucosal resection with ligating device.

A: Aspiration of a carcinoid tumor into the ligating device; B: Deployed elastic band; C: Snare resection performed below the band; D: A clear, post-endoscopic submucosal resection with ligating device ulcer.

ESD

Endoscopic submucosal dissection is considered a valuable endoscopic treatment for early gastric cancer and large superficial gastric neoplasms. This technique provides a higher en bloc and histologically complete resection rate than EMR, enables accurate pathologic diagnoses, and is less invasive than surgery (Figure 5)[23]. Recently, ESD has been applied to the treatment of large colorectal neoplasms and has been reported to be more effective than either EMR or EMR-precutting[24]. However, ESD has the disadvantage of a considerably higher risk for perforation because the technique involves dissection of the submucosal tissue beneath the lesion. In addition, highly trained endoscopists are required. Thus, the safety issues associated with this technique must be solved. As a result, ESD is not yet widely accepted for the treatment of colorectal neoplasms[25].

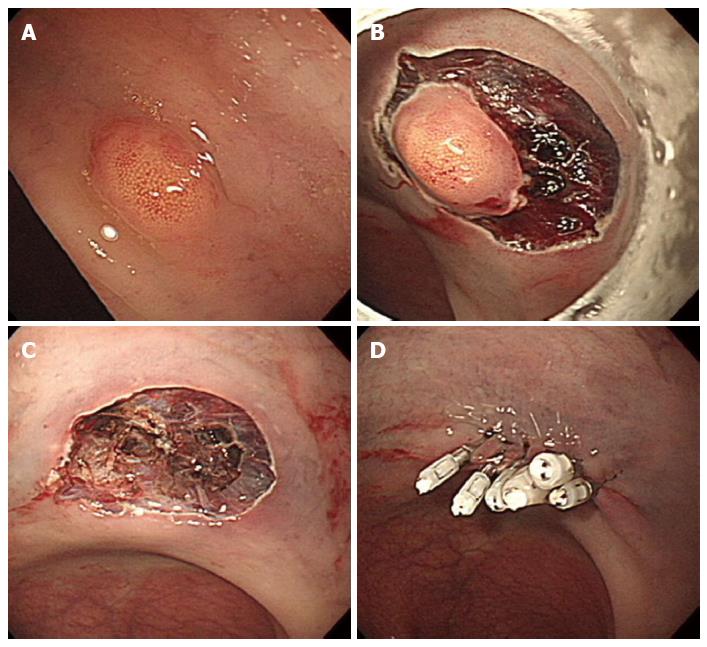

Figure 5 Endoscopic submucosal dissection.

A: An approximately 5 mm rectal carcinoid tumor; B: Mucosal incision and submucosal dissection; C: A clear, post-endoscopic submucosal dissection ulcer; D: Endoscopic closure of the ulcer floor with endoclips.

There have been few studies reporting the efficacy and safety of ESD for the resection of rectal carcinoids. Recently, Onozato et al[26] reported that ESD was technically feasible in five cases with rectal carcinoids less than 10 mm. In addition, no complications were observed, and all lesions were completely resected histologically. In a meta-analysis including four studies[27-30], ESD was a more effective procedure for the treatment of rectal carcinoids and had a higher complete resection rate than EMR[31]. ESD was more effective than EMR in complete histological resection [odds ratio, 0.29; 95%CI: 0.14-0.58; P = 0.000]. Additionally, ESD was as safe as EMR (rate difference, -0.01; 95%CI: -0.07 - 0.05; P = 0.675). The recurrence rate did not differ significantly between the EMR and ESD groups. The duration of ESD was longer than EMR. Because the rectum is fixed in the retroperitoneum, the risk of peritonitis following perforation is lower than in other parts of the colon. One of limitations of ESD with a knife is the inability to fix the knife to the target lesion, which leads to high complications such as bleeding and perforation. New grasping type scissor forceps, which can grasp and incise the targeted tissue using an electrosurgical current, may reduce these complications[32]. More recently, there have been a few studies comparing ESD to other endoscopic treatment modalities besides EMR. Kim et al[33] reported a large retrospective analysis including 115 patients, which were classified into an EMR group (n = 33), ESMR-L group (n = 40), and ESD group (n = 44). The curative resection rate in the EMR group was 77.4%, which was significantly lower than that of the ESMR-L (95%) and ESD groups (97.7%). This result suggests that ESMR-L and ESD may be superior to conventional EMR. A recent study by Choi et al[25] comparing ESMR-L (n = 29) with ESD (n = 31) for the endoscopic treatment of rectal carcinoids showed that the complete resection rate was 80.6% in the ESD group and 82.8% in the ESMR-L group (P = 0.833). The resection time was significantly longer in the ESD group than in the ESMR-L group. The authors concluded that ESMR-L might be considered the treatment of choice for small rectal carcinoid tumors because of reduced procedure time. A small comparative study by a Japanese group[34] also showed a similar result to the above study. A retrospective analysis of 3 types of endoscopic resection technique by Zhao et al[35] demonstrated that complete resection rates using the EMR, EMR-C, and ESD were 80%, 100%, and 100%, respectively. The average procedure time was the shortest in the EMR-C group. This study concluded that EMR-C might be the best endoscopic excision method, considering the clinical efficacy, surgical time, and complication rate.

TEM

Transanal endoscopic microsurgery was originally designed by Buess et al[36] in the 1980s. The procedure allows full thickness excisions as high as 20 cm from the anal verge to be performed using a 40-mm operating rectoscope. Although TEM is not superior to conventional transanal excision (TAE) for resecting lesions in the lower rectum, it has distinct advantages for removing lesions in the mid and upper rectum[37]. In addition to improved access to more proximal lesions, TEM provides several advantages over TAE, including improved visualization with better exposure, higher likelihood of achieving clear resection margins, and lower recurrence rates[38]. The application of TEM for rectal carcinoids has been described in several small case series[6]. Kinoshita et al[39] reported clinical experience including 27 patients with rectal carcinoids treated by TEM. In this study, TEM was performed as a primary excision (n = 14) or as completion surgery after incomplete resection by endoscopic polypectomy (n = 13). Negative margins were obtained in all cases. There was no additional radical surgery performed, and patients were followed-up for 70 mo without recurrence. The largest series in the United States included 24 patients over a 12-year period[40]. There were 6 (25%) primary surgical resections, and 18 (75%) resections were performed after incomplete snare excisions during colonoscopy. This study showed all negative margins, a similar zero rate of recurrence and a similarly low morbidity rate. In addition to its usefulness in primary surgical resection of rectal carcinoids especially in the mid and upper rectum, TEM can be used as a salvage treatment after incomplete resection by endoscopic polypectomy. The possible complications of TEM include bleeding and perforation. In addition, transient soiling can occur due to the large width of the rectoscope tube[37].

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES AND CONCLUSIONS

In rectal carcinoids estimated endoscopically as < 10 mm in diameter, endoscopic treatment is a feasible option. Although endoscopic resection of rectal carcinoids with conventional polypectomy or EMR is a simple procedure, it is difficult to achieve histologically complete resection. EMR-C, ESMR-L, and ESD showed similar efficacy and safety. However, there are currently limited comparative data to recommend a specific endoscopic treatment. Therefore, the choice of treatment modalities for small rectal carcinoids depends on the degree of endoscopic or surgical expertise at a given facility. Furthermore, any one of the above treatment methods could have a favorable clinical outcome if performed by gastroenterologists or surgeons with special techniques.

Endoscopic treatment for rectal carcinoid requires special techniques for a deeper resection to achieve clear margins. For this purpose, lesions are usually lifted using submucosal injection with saline solution with or without epinephrine. In addition, adequate submucosal injection is important for the reduction of thermal damage to tissue as well as the prevention of complication such as bleeding or perforation. Although electrocauterization during endoscopic resection could destroy remnant tumor, its burning or coagulation artifact may make the pathologic examination of resection margin difficult. Therefore, to separate the margin of carcinoid tumor from the underlying muscle layer adequately could provide better pathological assessment of radial margins and the depth of invasion[41].

EMR-C and TEM can be used as a salvage treatment after incomplete resection by conventional polypectomy or EMR. However, the efficacy of ESMR-L and ESD for salvage treatment requires further investigation. Endoscopic tattooing of colonic lesions helps to localize polypectomy sites that may difficult to identify with repeat endoscopy[42]. In cases with positive resection margin after endoscopic treatment of rectal carcinoids, tattooing the area of resection will help facilitate the lesion site location for further resection.

Newly developed over-the-scope clip (OTSC) has a higher compression force and the capacity to capture a larger volume of tissue than the through-the-scope clip[43]. Recent prospective study has shown that perforations occurring after full- thickness resection of gastric subepithelial tumors less than 3 cm could be managed by OTSC closure[44]. Although further prospective clinical trial is required, this study suggests that endoscopic full-thickeness resection with OTSC closure can be applied to selected patients with colonic subepithelial lesions to have malignant potential. Finally, a prospective large-scale study is warranted for the assessment of therapeutic efficacy of various endoscopic treatments and long-term outcome.

P- Reviewer Königsrainer AA S- Editor Ma YJ L- Editor A E- Editor Liu XM