Published online Mar 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i3.98021

Revised: November 11, 2024

Accepted: February 8, 2025

Published online: March 16, 2025

Processing time: 271 Days and 20.1 Hours

Hemostatic powders have been used as primary or salvage therapy to control gastrointestinal bleeding in a number of scenarios. PuraStat® is a novel, self-assembling peptide gel that has properties that differ from hemostatic powders. It is transparent, can be used in narrow spaces and combined with other modalities. Also, it is pre-filled in a syringe ready to use and easy to handle and deliver. PuraStat® has been shown to be effective and safe in treating gastrointestinal bleeding lesions. But, its role as a hemostatic agent in all bleeding indications remains to be clarified.

To evaluate PuraStat® efficacy and its applications, feasibility and safety in treating gastrointestinal bleeding lesions.

We performed a retrospective single-centre analysis of all consecutive patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, that required endoscopic treatment and where PuraStat® was applied, from June 2020 to October 2022. Demographics, bioche

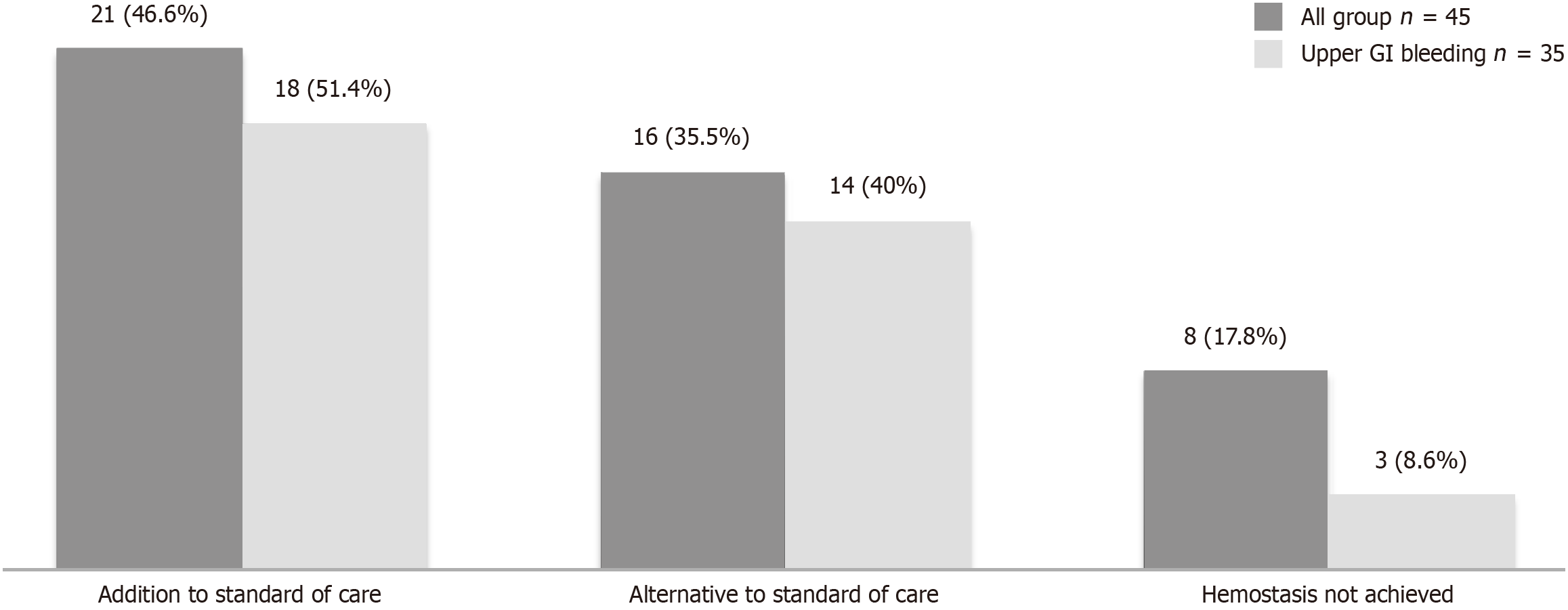

In total 45 patients were included, and 17/45 (37.8%) females. The mean age was 65.8 years. Charlson score was > 2 in 27/45 (60%) and 26/45 (57.8%) required transfusion. The procedures were gastroscopy (77.8%), colonoscopy (15.5%), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (4.4%) and enteroscopy (2.2%). The most common bleeding lesion was peptic ulcer (33.3%). PuraStat® was used alone in 36% of the cases. One hundred percent achieved initial hemostasis and no complications were documented. There were no significant differences between the use of PuraStat® alone or in combination in terms of re-bleeding (P = 0.64) or mortality (P = 0.69). In 46.6% of cases, the reason for applying PuraStat® was as addition to standard of care, in 35.5% as an alternative because standard of care was not possible and in 17.8% as a rescue therapy.

PuraStat® is an effective therapy for multiple etiologies and is considered very easy to use in the majority. Its role as front line agent should be considered in the future.

Core Tip: This study shows that PuraStat® is safe, effective and easy to use as hemostatic agent in multiple gastrointestinal bleeding sources, including lesions responsible for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. This is significant because many times, the standard of care treatment, such as sclerosant agents, hemoclips or soft coagulation forceps are not available or cannot be applied due to the lesions are placed in difficult positions, or there is underlying fibrosis of a diffuse bleeding.

- Citation: Ballester R, Costigan C, O'Sullivan AM, Sengupta S, McNamara D. Efficacy and applications for PuraStat® use in the management of unselected gastrointestinal bleeding: A retrospective observational study. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(3): 98021

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i3/98021.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i3.98021

Endoscopic therapy is the accepted first-line treatment modality in the management of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing the rate of re-bleeding, the need for surgical intervention, and overall mortality. The standard therapy used to control bleeding in non-variceal upper GI bleeding (UGIB), depends on the type of bleeding lesion and includes injection therapy, thermal therapy, mechanical therapy with clips or a combination[1,2]. These modalities of treatment are not all widely available in all countries and their use can often be challenging due to the anatomic position of the target lesion, underlying fibrotic tissue or the presence of diffuse bleeding.

Hemostatic powders have been used as primary or rescue therapy to control GI bleeding in a number of scenarios. They are also being used increasingly in the management of UGIB. These topical agents, in comparison to other modalities, have the advantage of ease of use due to a lack of need for precise targeting, easier access to lesions in difficult locations, and the ability to treat a larger surface area. In general, hemostatic powders have been shown to be effective, with reported immediate efficacy of between 86% to 100%[3-10].

The most significant theoretical limitation of hemostatic powders, as opposed to other modalities, is that they only bind to sites with active bleeding and usually wash away within 12-24 hours; leading to possible re-bleeding rates as high as 19% at 72 hours when used to treat non-variceal UGIB[11]. Another drawback of these hemostatic powders is that they are opaque, once administered they do not allow visualisation of the underlying mucosa hence limiting further endoscopic assessment and treatments. Moreover, there is an increasing concern about its use can damage the scopes. Thus, they are traditionally seen as a temporary measure[2].

PuraStat® (3-D Matrix Europe SAS. France) is a novel viscous solution of synthetic peptides. The peptides self-assemble to form a 3-dimensional matrix upon a change in pH caused by exposure to an ionic solution such as blood, peritoneal fluid or other bodily secretions. It is presented in a pre-filled syringe and applied via a dedicated endoscopic catheter (PuraStat® Nozzle System Type-E. 2.8 mm. TOP Corporation. Tokyo. Japan). This catheter can be introduced through the working channel of any diagnostic or therapeutic endoscope.

PuraStat® has some properties that differ from hemostatic powders. It is transparent, it does not block the field of view, so it is possible to check the post-therapy bleeding status and continue with further intervention if necessary. It is also versatile, can be used in narrow spaces and as an adjunct with other modalities of treatment. Finally, it is user-friendly, as it is a pre-filled syringe ready to use and easy to handle and deliver.

To date published data on the role of PuraStat® as hemostatic agent has mostly been in a surgical setting. When it comes to endoscopy, the majority of publications refer to role of PuraStat® in post- endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or post- endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) bleeding control, and in the acceleration of the wound healing. Subramaniam et al[12], showed PuraStat® was effective as a single agent in controlling intraprocedural bleeding in 75% of cases. Later, the same author published a randomized clinical trial showing that PuraStat® is an effective hemostatic agent, that can reduce the need for heat therapy for bleeding during ESD and that has an interesting role in improving the healing[13].

Three published studies assessed the efficacy of PuraStat® as a hemostatic agent in UGIB. This agent was used as a primary or salvage therapy, alone or in combination with other modalities. The hemostasis was achieved in more than 90% of the cases with re-bleeding rates between 10% and 18%respectively and with a high safety profile[14-16]. The results are promising, but its role as a hemostatic agent in all bleeding indications, its efficacy (particularly long term) and usability remains to be confirmed.

We conducted a retrospective observational study at a single teaching public hospital (Tallaght University Hospital, Tallaght, Dublin 24) serving a catchment of 650000 people. In the Endoscopy unit, between 10 to 15 endoscopies per month are performed because of GI bleeding. We enrolled all consecutive patients that underwent an endoscopy treatment because of bleeding, where PuraStat® was applied from June 2020 to October 2022. We excluded those patients with bleeding lesions where PuraStat® was not used or when data was incomplete or unavailable. The patients were identified from the Endoscopy Department Database. The identification was performed in a daily basis at the end of the working day.

All procedures were performed or supervised by consultant gastroenterologists with more than 5 years of experience in the management of GI bleeding. Antithrombotic and anticoagulant agents are managed similarly in all the patients per protocol, following the ESGE guidelines[2]. The standard of care (SOC) treatment included: Injection (sclerosing agents and/or Adrenaline), hemoclips, Argon Plasma Coagulation and banding. The decision to apply PuraStat® was at the endoscopist discretion based on each patient individual condition. PuraStat® had already been approved and introduced in our hospital as hemostatic agent. We collected demographics, clinical and biochemical data as well as endoscopic findings from the electronic patient record. The Charlson score index was calculated for all the patients[17]. We requested the endoscopists to specify the reason why they used PuraStat® and were classify in three categories: hemostasis not achieved with SOC (salvage therapy); SOC not possible to apply because difficult position, fibrosis or large surface area to treat; or as addition to SOC when the endoscopist felt that the SOC was not sufficient and there was a high risk of bleeding recurrence. Endoscopists were also asked to provide their experience of using PuraStat® in a scale: Very easy (no difficulties encountered), intermediate (some difficulties with mild effort needed to apply the gel) or difficult (need more effort or skills to apply the gel). Indications for endoscopy, findings and outcomes were recorded. Forrest classification was used for gastric and duodenal ulcers[18]. Initial hemostasis was considered achieved when active bleeding ceased completely, and persistent bleeding was the continuance of active bleeding despite the application of hemostatic modalities. ‘Re-bleeding’ was defined as recurrence of haematemesis, melaena and/or haematochezia; recurrence tachycardia (heart rate > 100 ppm) or hypotension (blood pressure < 100 mmHg) after having reached hemodynamic stability; or a reduction in haemoglobin (Hb) ≥ 2 g/dL after a stable Hb value had been attained. Both ‘re-bleeding’ and survival rates at 30 days post PuraStat® application were assessed. The occurrence of adverse events related to the use of PuraStat® or to the endoscopic procedure were also registered.

The primary outcome of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of PuraStat® at achieving initial hemostasis and at preventing re-bleeding. Also we aimed to assess its applications, feasibility and safety in treating GI bleeding lesions.

Means with SD and/or interquartile ranges were used to describe continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. For associations between variables and outcome, χ2 or Fisher´s exact test were used for categorical, and Student t-test or ANOVA/Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis test, for continuous variables. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the primary outcome measure. Risk ratio (RR) Wald and Fisher test were used to test relative risks. The statistics analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics® software (Version 24; IBM Corp., Aemink, NY, United States)

This study was approved by the Saint James’s Hospital and Tallaght University Hospital Joint Research and Ethics Committee (No. 2395), Dublin, Ireland. The requirement for the acquisition of informed consent from patients was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study.

In total 45 patients were identified and recruited, representing the 15% of total GI bleeding cases during the study period (1 patient in 2020, 14 patients in 2021 and 30 patients in 2022). Of 17 (37.8%) were female and the mean age was 65.8 years. The general demographic, biochemical and endoscopic data are shown in Table 1. As patients with active bleeding can deteriorate over time, we registered clinical parameters on admission and at 24 hours. Charlson score was > 2 in the majority of the patients (27/45, 60%) and more than half required blood transfusion (26/45, 57.8%). The most common procedure was gastroscopy (n = 35) followed by colonoscopy (n = 7). All the colonoscopies were cases of polyp EMR. Peptic ulcer (n = 15) and post-EMR bleeding (n = 8) were the most common sources of bleeding. Nine cases included findings of angiodysplasia (n = 2), post variceal banding scar (n = 2), Dieulafoy lesion (n = 1), Mallory Weiss tear (n = 2) and surgical anastomosis (n = 2).

| Variable | Value |

| Demographic data | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 65.8 ± 13.2 |

| Gender | Female 17 (37.8)/male 28 (62.2) |

| Antiplatelet (aspirin 4, aspirin + clopidogrel 1, clopidogrel 1, prasugel 1) | 7 (15.6) |

| Anticoagulant (DOAC 8, Warfarin 2, Heparin 1) | 12 (26.7) |

| PPI | 27 (60) |

| Charlson index score | |

| 0 | 7 (15.6) |

| 1-2 | 11 (24.4) |

| 3-4 | 18 (40) |

| ≥ 5 | 9 (20) |

| Transfusion | 26 (57.8) |

| Type of episode | |

| First episode | 31 (68.9) |

| Re-bleeding | 13 (28.9) |

| Second look | 1 (2.2) |

| Biological data (mean ± SD) | |

| BP initial | 113 ± 24.4 |

| BP lower 24 hours | 107 ± 23.1 |

| HR initial | 91.7 ± 21.7 |

| HR higher 24 hours | 95.9 ± 21.3 |

| Hb initial | 9.2 ± 2.6 |

| Hb lower 24 hours | 8.3 ± 2.6 |

| Endoscopic data | |

| Type of procedures | |

| Gastroscopy | 35 (77.7) |

| Colonoscopy | 7 (15.5) |

| ERCP | 2 (4.4) |

| Enteroscopy | 1 (2.2) |

| Type of lesions | |

| Peptic ulcer | 15 (33.3) |

| Postpolypectomy bleeding | 8 (17.8) |

| Neoplasia | 6 (13.3) |

| Peptic oesophagitis | 5 (11.1) |

| Post-sphincterotomy | 2 (4.4) |

| Others | 9 (20) |

PuraStat® was used alone in 16 cases (36%) (14 in UGIB and in 2 cases post-EMR) and in 29 patients (64%) was used in combination with other modalities of treatment (Adrenaline injection in 13 cases, Adrenaline + hemoclip in 7, hemoclip in 5, Argon Plasma Coagulation in 2, hemoclip + Argon Plasma coagulation in 1 case and banding in 1 case). The mean amount of PuraStat® applied was 2.9 mL (SD 1.1).

Analysis of initial hemostasis rate, re-bleeding rate and mortality was performed in the whole cohort as well as in the subgroup with UGIB.

Overall, initial haemostasis success was achieved in all cases and no intra-procedural complications were documented with the application of PuraStat® or with other treatments. In all, 5 patients re-bled within 30 days (11.1%). Of those, one patient with a duodenal ulcer underwent surgery and one with neoplasia required arterial embolization via interventional radiology.

A total of 8 patients (17.8%) had died within 30 days of endoscopic treatment, leading an overall survival of 82.2% (95%CI: 67.9%-92.0%).

All patients that re-bled and/or died were patients that presented with UGIB. Among the patients that died, the cause of death in 4 cases was comorbidities exacerbated by the bleeding, and the other 4, because of unrelated underlying comorbidities.

There were no statistically significant differences between the use of PuraStat® alone or in combination with other modalities in terms of re-bleeding (6.25% vs 13.8%, with a RR of 0.45 and 95%CI: 0.06-3.72, P = 0.64) or mortality (12.5% vs 20.7%, with a RR of 0.6 and 95%CI: 0.14-2.65, P = 0.69).

However, the survival was significantly lower in patients that received blood transfusion (69.2% vs 100%, RR of 0.69, P = 0.014), that re-bled (20% vs 90%, RR of 0.22, P = 0.002) and patients with a Charlson score > 2 (70.2% vs 100%, RR of 0.702, P = 0.01; Table 2).

| Mortality yes/no | P value | |

| All patients outcome, n = 45 | ||

| PuraStat® alone | 2 (12.5)/14 (87.5) | 0.69 |

| In combination | 6 (20.7)/23 (79.3) | |

| Blood transfusion | ||

| Yes | 8 (30.8)/18 (69.2) | 0.014 |

| No | 0 (0.0)/19 (100) | |

| Rebleeding | ||

| Yes | 4 (80)/1 (20) | 0.002 |

| No | 4 (10)/36 (90) | |

| Charlson score (mean ± SD) | 4.67 ± 2.8/2.69 ± 2.0 | 0.081 |

| Charlson score | ||

| ≤ 2 | 0 (0.0)/18 (100) | 0.01 |

| > 2 | 8 (29.8)/19 (70.2) | |

| Subgroup UGIB n = 35 | ||

| PuraStat® alone | 2 (14.3)/12 (85.7) | 0.43 |

| In combination | 6 (28.6)/15 (71.4) | |

| Charlson score | 0.046 | |

| ≤ 2 | 0 (0.0)/13 (100) | |

| > 2 | 8 (36.4)/14 (63.6) |

The 35 patients presenting with UGIB underwent gastroscopy. The specifics of this subgroup are shown in Table 3. The re-bleeding rate in this subgroup within 30 days was 14.3% (5 patients). The survival rate in this group within 30 days was 77% (8 patients died) (95%CI: 25.3-29.7). Again, in this group there where no statistically significant differences between the use of PuraStat® alone or in combination with other modalities in regard re-bleeding (7.1% vs 19%, with a RR of 0.38 and 95%CI: 0.05-3.01, P = 0.63) or mortality (14.3% vs 28.6%, with a RR of 0.5 and 95%CI: 0.12-2.13, P = 0.43). In this subgroup, also patients only with Charlson score > 2, compared to score ≤ 2, showed a significant higher mortality (36.4% vs 0%, P = 0.046; Table 2).

| Variable | Value |

| Demographic data | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 65.8 ± 13.7 |

| Gender | Female 15 (42.9)/male 20 (57.1) |

| Antiplatelet (aspirin 3, clopidogrel 1) | 4 (11.4) |

| Anticoagulant (DOAC 8, warfarin 2, heparin 1) | 10 (28.6) |

| Charlson index score | |

| 0 | 5 (14.3) |

| 1-2 | 8 (22.9) |

| 3-4 | 13 (37.1) |

| ≥ 5 | 9 (25.7) |

| Transfusion | 26 (74.3) |

| Type of episode | |

| First episode | 22 (62.9) |

| Re-bleeding | 12 (34.3) |

| Second look | 1 (2.9) |

| Biological data (mean ± SD) | |

| BP initial | 111 ± 25.5 |

| BP lower 24 hours | 103 ± 22.9 |

| HR initial | 94.2 ± 22.8 |

| HR higher 24 hours | 98.5 ± 22.6 |

| Hb initial | 8.5 ± 3.6 |

| Hb lower 24 hours | 7.6 ±2.6 |

| Endoscopic data | |

| Type of lesions | |

| Peptic ulcer | 15 (42.8) |

| Neoplasia | 6 (17.1) |

| Peptic oesophagitis | 5 (14.3) |

| Vascular | 3 (8.5) |

| Post polypectomy bleeding | 1 (2.9) |

| Others | 5 (14.3) |

| Ulcer Forrest | Ib 3 (20), Ia 6 (40), IIb 3 (20), IIc1 (6.7), III 2 (13.3) |

In the 2 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) cases, one was a bleeding post-sphincterotomy and another after pre-cut. In both cases the reason from applying PuraStat® was because hemostasis was not achieved with the initial treatment applied (Adrenaline injection and/or hemoclip. No rebleeding or mortality was documented in these two cases.

The reasons why PuraStat® was used overall and in the UGIB subgroup are shown in Figure 1. In the majority of the cases (22/45 and 18/35 in the whole cohort and UGIB cohort respectively), the reason for applying the gel was as addition to SOC; in 16/45 and 14/35 cases as an alternative because SOC was not possible and in 8/45 and 3/35 cases (two cases of angiodysplasia and one ulcer Forrest IIb), as a rescue therapy because hemostasis was not achieved with SOC.

This subgroup of 16 cases (35.5%) included 14 gastroscopies (87.5%) and 2 colonoscopies (12.5%). The gastroscopy findings were: 3 peptic oesophagitis (18.8%) with oozing bleeding, 4 duodenal ulcers (25%) (Forrest IIa, IIb, IIc and III), 4 neoplasias (26%) with diffuse bleeding and 1 post-banding scar, 1 Mallory Weiss tear and 1 anastomosis with oozing bleeding. 2 cases were bleeding post colonic EMR.

The use of PuraStat® was reported to be “very easy” or “intermediate” in almost all the cases (40/45, 88.9%). No catheter clogging or kinking was encountered and no procedure related complications were registered either.

This study shows that PuraStat® is effective in achieving hemostasis in different bleeding scenarios, that is feasible, safe and that its use is being increased in recent years.

Our cohort of patients in terms of demographics and endoscopic findings is representative of the real general population that normally attends hospital with a GI bleeding. A quarter of the patients were on anticoagulant therapy (26.7%), 57.8% had required blood transfusion, and 60% had a Charlson score greater than 2, representing a high risk of mortality due to underlying comorbidities.

The efficacy of PuraStat® in controlling the initial bleeding was 100% in this series, although 5 patients re-bleed, representing 11.1% and the 14.3% in the whole group and UGIB sub-group respectively. In terms of initial hemostasis success, this study is comparable to previous studies that analysed PuraStat®. A retrospective, observational consecutive case series study, analysed different types of lesions and procedures (gastroscopy, ERCP and EMR). PuraStat® succeed in achieving hemostasis in 90.4% of the cases with a re-bleeding rate of 10.4%[14]. A prospective multicentre observational study, reported up to 94% of initial hemostasis succeed after primary application of PuraStat® although no cases of spurting bleeding were included. The overall re-bleeding at 30th day of follow up was 16%[15]. A retrospective analysis recently published with a small cohort, reported an efficacy of 92%[16].

The mortality reported in our study was 17.8% in the whole group and 22.8% in the UGIB group. This is slightly increased compared with the mortality normally reported in this setting (around 10%) and unchanged over the last 50 years[19,20]. Nevertheless, we analyzed the risk factors associated with the mortality in this series and were blood transfusion (P = 0.014), presence of rebleeding (P = 0.002) and Charlson score > 2 (P = 0.01). All the patients that died, re-bled beforehand and had a high Charlson score. Hence, we believe that the prognosis in this cohort of patients with GI bleeding was influenced by many factors besides the type of endoscopic treatment.

Unlike other studies, our study details the reasons why the gel was used. In most cases, PuraStat® was applied as an addition to the SOC, which make sense, as PuraStat® is not accepted as an initial single therapy. However, is quite significant that up to 40% of the cases with UGIB was used as alternative to SOC because SOC was not possible. This highlight one of the advantages of PuraStat® over the SOC: It can be applied in very difficult locations where the application of hemoclip or even a thermal probe is difficult to reach. Of note, in 3 cases in the UGIB subgroup (two angiodysplasias and one ulcer) it was applied as a rescue therapy and was effective in achieving initial hemostasis.

PuraStat® was considered very easy to use in the majority of cases. The few cases that was considered difficult were cases where the lesion was placed in the upper part of the lumen. The difficulty had nothing to do with the gel application, was due to the fact that with gravity the gel slipped and did not remain entirely on the site.

There are few drawbacks in this study. The retrospective nature is notable, however, this is a novel treatment and its use is still not widespread. Thus the experience in using this agent as treatment for GI lesions is limited and only small case series or retrospectives studies are currently available. In addition, little data has previously been reported with the use of PuraStat® alone, and our study shows the results in 16 patients. Another limitation is the variety of sources of bleeding. However, we made a sub-analysis in only patients with UGIB to homogenize the cases and to improve the accuracy. In any case, the variety of bleeding sources reflects the real practice and how versatile this gel is as it can be used in multiples settings.

In our study, PuraStat® has been shown to be a promising hemostatic tool whose use is increasing. Its main strength compared to previous powders and to the SOC modalities is its easy use and transparency and the ability to reach difficult positions. Future studies are necessary to validate its role in specific bleeding lesions and to confirm its efficacy in both, immediate and permanent hemostasis.

| 1. | Pedroto I, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T. Is timely endoscopy the answer for cost-effective management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding? Endoscopy. 2012;44:721-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gralnek IM, Stanley AJ, Morris AJ, Camus M, Lau J, Lanas A, Laursen SB, Radaelli F, Papanikolaou IS, Cúrdia Gonçalves T, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Awadie H, Braun G, de Groot N, Udd M, Sanchez-Yague A, Neeman Z, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2021. Endoscopy. 2021;53:300-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 66.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Haddara S, Jacques J, Lecleire S, Branche J, Leblanc S, Le Baleur Y, Privat J, Heyries L, Bichard P, Granval P, Chaput U, Koch S, Levy J, Godart B, Charachon A, Bourgaux JF, Metivier-Cesbron E, Chabrun E, Quentin V, Perrot B, Vanbiervliet G, Coron E. A novel hemostatic powder for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a multicenter study (the "GRAPHE" registry). Endoscopy. 2016;48:1084-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rodríguez de Santiago E, Burgos-Santamaría D, Pérez-Carazo L, Brullet E, Ciriano L, Riu Pons F, de Jorge Turrión MÁ, Prados S, Pérez-Corte D, Becerro-Gonzalez I, Martinez-Moneo E, Barturen A, Fernández-Urién I, López-Serrano A, Ferre-Aracil C, Lopez-Ibañez M, Carbonell C, Nogales O, Martínez-Bauer E, Terán Lantarón Á, Pagano G, Vázquez-Sequeiros E, Albillos A; TC-325 Collaboration Project, Endoscopy Group of the Spanish Association of Gastroenterology. Hemostatic spray powder TC-325 for GI bleeding in a nationwide study: survival and predictors of failure via competing risks analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:581-590.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baracat FI, de Moura DTH, Brunaldi VO, Tranquillini CV, Baracat R, Sakai P, de Moura EGH. Randomized controlled trial of hemostatic powder versus endoscopic clipping for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:317-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Alzoubaidi D, Hussein M, Rusu R, Napier D, Dixon S, Rey JW, Steinheber C, Jameie-Oskooei S, Dahan M, Hayee B, Gulati S, Despott E, Murino A, Subramaniam S, Moreea S, Boger P, Hu M, Duarte P, Dunn J, Mainie I, McGoran J, Graham D, Anderson J, Bhandari P, Goetz M, Kiesslich R, Coron E, Lovat L, Haidry R. Outcomes from an international multicenter registry of patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding undergoing endoscopic treatment with Hemospray. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:96-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Beg S, Al-Bakir I, Bhuva M, Patel J, Fullard M, Leahy A. Early clinical experience of the safety and efficacy of EndoClot in the management of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E605-E609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Prei JC, Barmeyer C, Bürgel N, Daum S, Epple HJ, Günther U, Maul J, Siegmund B, Schumann M, Tröger H, Stroux A, Adler A, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Jürgensen C, Wentrup R, Wiedenmann B, Binkau J, Hartmann D, Nötzel E, Domagk D, Wacke W, Wahnschaffe U, Bojarski C. EndoClot Polysaccharide Hemostatic System in Nonvariceal Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Results of a Prospective Multicenter Observational Pilot Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:e95-e100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vitali F, Naegel A, Atreya R, Zopf S, Neufert C, Siebler J, Neurath MF, Rath T. Comparison of Hemospray(®) and Endoclot(™) for the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:1592-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Park JS, Kim HK, Shin YW, Kwon KS, Lee DH. Novel hemostatic adhesive powder for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E1763-E1767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen YI, Barkun AN. Hemostatic Powders in Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Systematic Review. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2015;25:535-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Subramaniam S, Kandiah K, Thayalasekaran S, Longcroft-Wheaton G, Bhandari P. Haemostasis and prevention of bleeding related to ER: The role of a novel self-assembling peptide. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Subramaniam S, Kandiah K, Chedgy F, Fogg C, Thayalasekaran S, Alkandari A, Baker-Moffatt M, Dash J, Lyons-Amos M, Longcroft-Wheaton G, Brown J, Bhandari P. A novel self-assembling peptide for hemostasis during endoscopic submucosal dissection: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2021;53:27-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | de Nucci G, Reati R, Arena I, Bezzio C, Devani M, Corte CD, Morganti D, Mandelli ED, Omazzi B, Redaelli D, Saibeni S, Dinelli M, Manes G. Efficacy of a novel self-assembling peptide hemostatic gel as rescue therapy for refractory acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2020;52:773-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Branchi F, Klingenberg-Noftz R, Friedrich K, Bürgel N, Daum S, Buchkremer J, Sonnenberg E, Schumann M, Treese C, Tröger H, Lissner D, Epple HJ, Siegmund B, Stroux A, Adler A, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Autenrieth D, Leonhardt S, Fischer A, Jürgensen C, Pape UF, Wiedenmann B, Möschler O, Schreiner M, Strowski MZ, Hempel V, Huber Y, Neumann H, Bojarski C. PuraStat in gastrointestinal bleeding: results of a prospective multicentre observational pilot study. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:2954-2961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Murakami T, Kamba E, Haga K, Akazawa Y, Ueyama H, Shibuya T, Hojo M, Nagahara A. Emergency Endoscopic Hemostasis for Gastrointestinal Bleeding Using a Self-Assembling Peptide: A Case Series. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32099] [Cited by in RCA: 38306] [Article Influence: 1008.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Forrest JA, Finlayson ND, Shearman DJ. Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet. 1974;2:394-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 594] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Lowe D, Travis SP, Murphy MF, Palmer KR. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60:1327-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Saydam ŞS, Molnar M, Vora P. The global epidemiology of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding in general population: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:723-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |