Published online Nov 16, 2022. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v14.i11.684

Peer-review started: August 28, 2022

First decision: September 12, 2022

Revised: September 28, 2022

Accepted: October 27, 2022

Article in press: October 27, 2022

Published online: November 16, 2022

Processing time: 77 Days and 18.6 Hours

Endoscopic resection for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) is still considered a great challenge with a high risk of complications, including per

To assess the effectiveness and safety of endoscopic resection for duodenal GISTs.

Between January 2010 and January 2022, 11 patients with duodenal GISTs were treated with endoscopic resection. Data were extracted for the incidence of com

The incidence of successful complete resection of duodenal GISTs was 100%. Three cases (27.3%) had suspected positive margins, and the other 8 cases (72.7%) had negative vertical and horizontal margins. Perforation occurred in all 11 patients. The success rate of perforation closure was 100%, while 1 patient (9.1%) had suspected delayed perforation. All bleeding during the procedure was managed by endoscopic methods. One case (9.1%) had delayed bleeding. Postoperative infection occurred in 6 patients (54.5%), including 1 who developed septic shock and 1 who developed a right iliac fossa abscess. All 11 patients recovered and were discharged. The mean hospital stay was 15.3 d. During the follow-up period (14-80 mo), duodenal stenosis occurred in 1 case (9.1%), and no local recurrence or distant metastasis were detected.

Endoscopic resection for duodenal GISTs appears to be an effective and safe minimally invasive treatment when performed by an experienced endoscopist.

Core Tip: This study presents the findings on endoscopic resection for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Endoscopic resection of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors is a great challenge. This study aimed to assess the effectiveness and safety of endoscopic resection for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors. The rate of successful complete resection was 100%. Intraoperative perforation occurred in all 11 patients. The success rate of perforation closure was 100%. All 11 patients recovered. During the follow-up period (14-80 mo), duodenal stenosis occurred in 1 case (9.1%), and no local recurrence or distant metastases were detected.

- Citation: Wang ZZ, Yan XD, Yang HD, Mao XL, Cai Y, Fu XY, Li SW. Effectiveness and safety of endoscopic resection for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A single center analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2022; 14(11): 684-693

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v14/i11/684.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v14.i11.684

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are rare digestive mesenchymal tumors, characterized by differentiation towards the interstitial cells of Cajal[1]. They can occur in any part of the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly in the stomach (60%) and small intestine (30%), but only 4%-5% occur in the duodenum[2]. GISTs have a variety of clinical behaviors with potentially malignant tendency. Currently, the treatment strategy for GISTs is somewhat controversial[3]. Some studies show that active surveillance was a safe option for GISTs smaller than 20 mm or even 30 mm (excision is only considered when the tumor grows)[4,5]. However, GISTs have inherent potential for malignancy, and the real risk stratification of the lesions is only known after resection[6]. Therefore, several societies recommend resection if a diagnosis of GIST is made, unless a major morbidity is expected[7-9].

In comparison to gastric GISTs, duodenal GISTs have a higher risk of malignancy. In addition, the duodenum has special anatomical features. Once the tumor grows, the difficulty of the operation increases accordingly, increasing the risk of combined organ resection. Therefore, resection should be performed for localized or potentially resectable duodenal GISTs. Traditional surgical treatment methods include pancreaticoduodenectomy and local resection of duodenal lesions. However, these operations are traumatic and prone to serious complications, such as delayed bleeding, pancreatic leakage, bile leakage, or abdominal infection[10,11]. Furthermore, pancreaticoduodenectomy or segmental duodenectomy will inevitably reduce the patient’s quality of life. GISTs have unique biological characteristics and rarely have lymph node metastasis[9], which makes endoscopic resection of lesions an alternative. In recent years, the development of endoscopic minimally invasive technologies, such as endoscopic submucosal dissection, endoscopic submucosal excavation, and endoscopic full-thickness resection, has brought attention to endoscopic minimally invasive treatment of duodenal GISTs.

Thus far, there are few studies about endoscopic resection of duodenal GISTs, most of which have been case reports. A few studies have reported small series of cases[12,13]. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of endoscopic resection for duodenal GISTs.

From January 2010 to January 2022, 11 consecutive patients with pathologically confirmed duodenal GIST underwent endoscopic resection in our center. All patients were examined preoperatively by computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). In all cases, there were no signs of lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis, no other malignant tumors, and no coagulation dysfunction, and it was considered that the patient could tolerate endotracheal intubation and general anesthesia. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Taizhou Hospital of Zhejiang Province (Approval No. K20210611).

A single-accessory channel endoscope (Q260J; Olympus) and/or a dual-channel endoscope (GIF-2T240, Olympus) were used during the procedures. A transparent cap (ND-201-11802; Olympus) was attached to the tip of the endoscope. An insulated-tip knife (KD-611L, IT2; Olympus), hook knife (KD-620LR; Olympus), dual knife (KD-650Q; Olympus), or hybrid knife (ERBE, Tübingen, Germany) was used to dissect the submucosal layer and peel the tumor. A titanium clip (HX-600-135; Olympus and M00522600), an endoloop (Leo Medical Co., Ltd, Changzhou, China), and an over-the-scope clip (OTSC) (12/6 t-type, Ovesco Endoscopy AG) were used for wound closure. Other devices and accessories that were used included a high-frequency electronic cutting device (ICC 200; ERBE), an argon plasma coagulation unit (APC 300; ERBE, Tübingen, Germany), a hot biopsy forceps (FD-410LR; Olympus), a foreign body forceps (FG-B-24, Kangjin, Changzhou, China), a snare (SD-230U-20; Olympus), and a carbon dioxide insufflator (Olympus).

All operations were performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation by experienced endoscopists. All patients were fasted for ≥ 6-8 h with no water for 2 h before the operation. Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered.

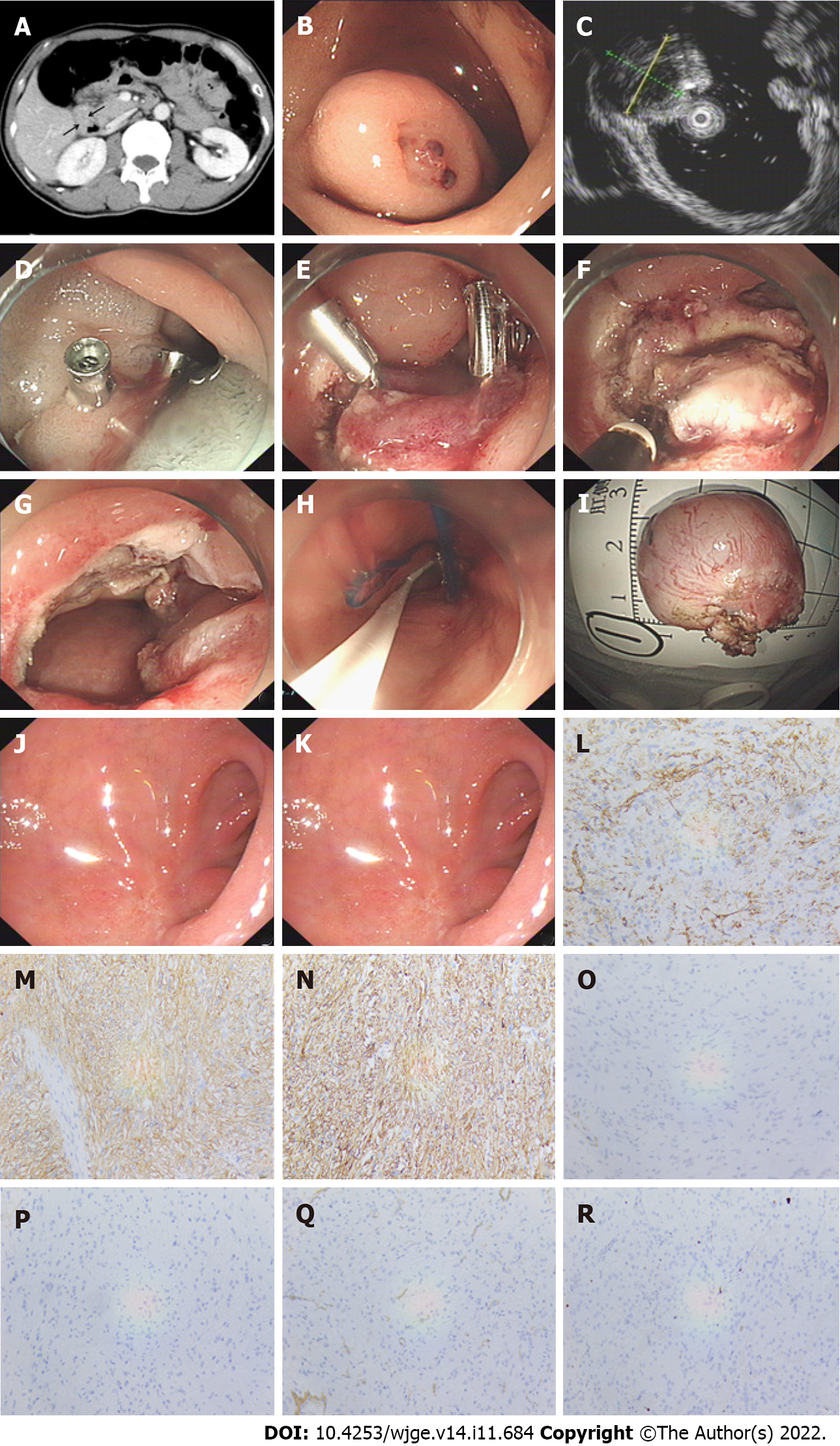

Endoscopic resection was conducted as follows (Figure 1A-K): (1) Several dots were marked around the lesion; (2) A mixture solution (100 mL normal saline +1 mL epinephrine + 2 mL indigo carmine) was then injected to elevate the submucosa; (3) Subsequently, a circumferential incision was made outside the border to expose the pseudo capsule; (4) Next, the submucosa and muscularis propria (MP) around the lesion were circumferentially dissected. After complete excision, the lesion was removed with a snare or foreign body forceps and sent for histopathological examination; and (5) The wound was closed with titanium clips, an OTSC, or an endoloop. If perforation occurred, a 20-gauge needle was used intraoperatively and postoperatively to relieve pneumoperitoneum.

A jejunal nutrition tube with the tip near the duodenal wound and a gastric tube were placed for drainage and detection of any postoperative hemorrhage. After the procedure, all patients were fasted and treated with a proton-pump inhibitor and prophylactic antibiotics. Oral intake was gradually resumed according to wound recovery.

After the operation, the resected specimens were observed and measured, and their size, shape, and envelope integrity were recorded. Then the specimens were immersed in 4% formaldehyde solution and fixed. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry were performed routinely. A diagnosis of GIST was confirmed if microscopic spindle cell proliferation was seen in the fasciculate, with staggered arrangement and positivity for CD117 or DOG-1 and CD34 (Figure 1L-R). The risk of recurrence after resection of GISTs was assessed according to the National Institutes of Health risk stratification system (2008 modified)[14].

Complete resection was considered if the lesion was resected en bloc with no obvious residual tumor at the resection site and with tumor-free margins according to histopathological examination[15]. Complications included intraoperative perforation, delayed perforation, intraoperative bleeding, delayed bleeding, and perioperative infection. Intraoperative perforation was considered if an extra-duodenal structure was visualized, retroperitoneal pneumatosis occurred, or free gas was detected by CT examination immediately after resection of the lesion[16]. Delayed perforation was considered if the patient experienced sudden abdominal pain after the procedure with a duodenal defect found under endoscopy or surgery. Intraoperative bleeding was regarded as a complication if one of the following criteria was met: (1) During the procedure, bleeding affected the visual field and could not be managed by endoscopic methods; (2) There was a significant reduction in hemoglobin (> 2 mg/dL); or (3) Blood transfusion was required[17]. Delayed bleeding was defined as hemorrhage from a post-procedure ulcer[18]. Local recurrence was defined as the detection of a lesion located on or adjacent to the scar of the previous endoscopic resection, which was then pathologically confirmed by biopsy[15].

Every patient underwent EUS at 3 mo after the operation to evaluate wound healing and check for residual lesions. The second surveillance endoscopy procedure was performed at 6 mo. Subsequently, gastroscopy and/or EUS was performed to detect tumor recurrence, and CT and/or abdominal ultr

Data were presented as the mean, median, number of cases, and percentage. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software program (version 20.0; SPSS Inc, Armonk, NY, United States).

The patient and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 11 patients (male, n = 9; female, n = 2) with duodenal GISTs underwent endoscopic resection at our center. The median age was 55 years (range: 33–74 years). Eight patients (72.7%) were symptomatic at presentation, with melena in 6 patients (54.5%), abdominal pain in 1 patient (9.1%), and abdominal distension in 1 patient (9.1%). Three tumors (27.3%) were detected incidentally during endoscopy for other reasons. All patients were negative for immunologic series and tumor markers (AFP, CEA, CA199, and CA125). Patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhaging showed fecal occult blood positivity and had anemia, with a minimum hemoglobin level of 36 g/L. All patients showed duodenal mass on abdominal CT before operation, which was enhanced after enhancement.

| Patient | Sex | Age, yr | Clinical presentation | Location | Size of maximum diameter, cm | Growth pattern | EUS appearance | Risk assessment | Specimen margin | Postoperative hospital stay, d | Follow-up, mo |

| 1 | M | 57 | Melena | Duodenal bulb | 2.2 | Mainly extraluminal growth | MP, hypoecho, uniform echo | Low risk | Negative | 9 | 14 |

| 2 | M | 56 | No symptoms | Descending junction of duodenal bulb | 2.0 | Intraluminal growth | MP, hypoecho, uniform echo | Very low risk | Negative | 15 | 19 |

| 3 | M | 68 | No symptoms | Descending duodenum | 3.0 | Partially extraluminal growth | MP, hypoecho, uniform echo | Low risk | Negative | 11 | 22 |

| 4 | M | 63 | Melena | Descending duodenum | 5.0 | Mainly extraluminal growth | MP, hypoecho, uniform echo | Low risk | Suspiciously positive | 16 | 30 |

| 5 | M | 52 | Melena | Descending duodenum | 1.5 | Intraluminal growth | MP, mixed echo, uneven echo | Very low risk | Negative | 8 | 33 |

| 6 | M | 53 | Melena | Descending junction of duodenal bulb | 3.5 | Mainly extraluminal growth | MP, hypoecho, uniform echo | Low risk | Suspiciously positive | 15 | 36 |

| 7 | M | 54 | Melena | Descending duodenum | 4 | Intraluminal growth | MP, hypoecho, uniform echo | Low risk | Suspiciously positive | 24 | 43 |

| 8 | M | 74 | Melena | Descending junction of duodenal bulb | 3.0 | Intraluminal growth | MP, hypoecho, uniform echo | Low risk | Negative | 26 | 50 |

| 9 | F | 33 | Abdominal pain | Descending duodenum | 3.0 | Intraluminal growth | MP, hypoecho, uniform echo | Low risk | Negative | 14 | 51 |

| 10 | F | 42 | No symptoms | Descending junction of duodenal bulb | 1.5 | Intraluminal growth | MP, hypoecho, uniform echo | Very low risk | Negative | 13 | 75 |

| 11 | M | 55 | Abdominal distension | Duodenal bulb | 2.0 | Intraluminal growth | MP, hypoecho, uniform echo | Very low risk | Negative | 12 | 80 |

The lesions were single in all 11 patients. The lesion was detected in the duodenal bulb in 2 cases (18.2%), in the descending junction of the duodenal bulb in 4 cases (36.4%), and in the descending part in 5 cases (45.4%). All lesions originated from the MP layer with intraluminal growth in 6 cases (54.5 %), partially extraluminal growth in 2 cases (18.2%), and mainly extraluminal growth in 3 cases (27.3%). EUS revealed hypoechoic structures in 10 cases (90.9%) and a mixed echoic structure in 1 case (9.1%). The median maximal diameter of these lesions was 3.0 cm (range: 1.5-5.0 cm). Immunohistochemistry of all lesions showed that CD34, CD117, and Dog-1 were positive, and Desmin and S-100 were negative. Nine cases (81.8%) were SMA positive. Four cases (36.4%) were Ki-67 < 1%, 3 cases (27.3%) were Ki-67 1%+, 3 cases (27.3%) were Ki-67 2%+, and 1 case (9.1%) was Ki-67 3%+.

Complete resection was successful in 100% of cases. Four patients (36.4%) were classified as very low risk, and 7 patients (63.6%) were classified as low risk. Among the 11 patients, a positive resection margin was suspected in 3 cases (27.3%) (tumor tissue was found at the electrocautery margin); all cases were pathologically low risk. The remaining 8 cases (72.7%) had negative lateral and basal margins. All 11 patients recovered and were discharged.

Perforation was detected in all 11 patients during the operation. The duodenal wall defect was occluded with several titanium clips + an endoloop in 1 case (9.1%), an OTSC in 6 cases (54.5%), and an OTSC + several titanium clips + an endoloop in 4 cases (36.4%). Intraoperative perforation closure was successfully performed in 100% of cases. Delayed perforation was suspected in 1 patient (9.1%) (as described below).

All 11 patients had bleeding during the procedure and were treated successfully using argon plasma coagulation and a hot biopsy forceps. A little coffee-colored liquid was drained from the gastrointestinal decompression tube in 1 case (9.1%) on the 1st d after the procedure, which improved after str

Six patients (54.5%) developed postoperative abdominal infection, and their anti-infection treatment was strengthened. Among them, 1 patient developed severe abdominal pain and septic shock on the day after endoscopic resection of a 3.0 cm × 2.5 cm tumor in the descending junction of the duodenal bulb. Emergency surgical exploratory laparotomy was performed immediately for suspected delayed perforation. During the operation, obvious edema was observed on the wound, but no obvious perforation was detected. This patient received peritoneal lavage and distal subtotal gastrectomy with resection of the duodenal bulb. Another patient developed a right iliac fossa abscess, which improved after puncture and drainage. One patient (9.1%) suffered malignant arrhythmia 5 d after the procedure and was transferred to the intensive care unit. All 11 patients recovered and were discharged. The mean time to the recovery of food intake after the operation was 8.1 d (range: 4-14 d). The mean postoperative hospital stay was 15.3 d (range: 8-26 d).

The wound healed well in all patients, and no recurrence or distant metastasis was detected during the follow-up period (median: 36 mo; range: 14-80 mo). Duodenal stenosis occurred in 1 patient (9.1%) whose previous tumor was in the descending junction of the duodenal bulb, and the wound was closed by an OTSC. The OTSC was found to block the lumen, and the endoscope could not pass through at 3 mo after the procedure. The patient was followed up, as he had no symptoms of obstruction. During endoscopic surveillance at 12 mo after the procedure, the OTSC detached spontaneously, and the lumen stenosis improved.

Endoscopic resection of duodenal lesions, especially subepithelial lesions, is still considered a cha

For localized GISTs, complete excision is the standard treatment. R0 resection is the goal in any case. A post hoc observational study showed that among patients with GISTs, when tumor rupture was excluded, there was no significant difference in overall survival of patients who received R0 and R1 resection[19]. Some studies also indicated that the recurrence rate of patients who received R1 resection did not differ from that of patients who received R0 resection[20,21]. Thus, if R0 resection is difficult to achieve, R1 resection (microscopically positive margins) may also be performed for low-risk GISTs in unfavorable locations[7]. If R1 resection was already performed, routine re-excision is not recommended[7], and the microscopic margin status should not be used to dictate adjuvant medical therapy decisions[19]. In our study, there were 3 cases in which microscopic involvement of the resection margins was suspected; all were low risk. No recurrence or distant metastasis was found during follow-up (30 mo, 36 mo, and 43 mo) without re-excision or adjuvant medical therapy.

Tumor rupture is an important adverse prognostic factor for the recurrence of GIST. It is defined by tumor spillage or fracture in the abdominal cavity, piecemeal resection, incisional biopsy, gastric or intestinal perforation to the abdominal cavity, blood-stained ascites at laparotomy, or transperitoneal microscopic infiltration of an adjacent organ[7]. In our study, the maximal diameter of all tumors was ≤ 5 cm and were resected en bloc. When the tumor size is > 5 cm in diameter, it is very difficult to resect it completely and take it out as a whole through the cardia, esophagus, and pharynx. Thus, for tumors larger than 5 cm, especially in intermediate- and high-risk cases, conventional surgery or laparoscopic and endoscopic cooperative surgery may be more appropriate.

In comparison to other parts of the digestive tract, the muscular layer of the duodenum is much thinner, and intraoperative perforation is prone to occur during endoscopic operations. In addition, digestive fluids, such as bile and pancreatic juice, can corrode the wound, and delayed perforation may subsequently occur. Injury to the duodenal muscularis and serosa should be avoided as far as possible in the case of perforation. However, when the lesion is closely associated with the MP or serosal layer of the duodenum, perforation is almost inevitable. Most duodenal GISTs originate from the MP, and the strategy “active perforation” is often adopted, resulting in a well-defined edge and mild edema. In some studies, perforation that could be closed by endoscopic methods during the endoscopic operation was not regarded as a complication[22,23].

With the development of endoscopic suture technology and the invention of OTSC, the OverStitch endoscopic suturing (ES) device and other suture devices, the success rate of wound suturing has been greatly improved. An OTSC has the following advantages: (1) It has great holding strength[24,25]; thus, it can grasp more tissue and clamp the entire wall of the lumen; (2) It is a bear trap-like, large clip with a wingspan of 12 mm, which can close full-thickness perforations of up to 3 cm in diameter[26]; and (3) The gap between the teeth of an OTSC allows blood to pass through to avoid tissue necrosis.

A systematic review showed that the rate of successful closure of the perforation by OTSC closure was 85.3%[27]. In our previous study, OTSC successfully closed the perforation after endoscopic re

In addition, purse-string suture technique, which is also widely used in iatrogenic digestive tract perforation, shows a high rate of successful sealing. Our previous study suggested that the closure rate of purse-string suture in endoscopic treatment of duodenal subcutaneous lesions was 100% (including 5 cases of perforation)[31]. In this study, duodenal wall defects were all successfully closed using OTSC, titanium, or purse-string suture according to the size of wound and wall defect. We placed two tubes, one with the tip in the gastric cavity to attract gas and gastric juice, and the other with the tip next to the duodenal wound to attract pancreatic juice and bile. Lessening tension of the wound and reducing the corrosion of digestive juice to the wound could effectively decrease the occurrence of delayed per

Another serious complication of endoscopic resection of duodenal GISTs is perioperative infection followed by perforation. In this study, 6 patients had postoperative abdominal infection, including 1 who developed septic shock and another who developed an abscess in the right iliac fossa. During the procedure, suction should be carried out in a timely manner in order to prevent excessive blood, intestinal contents, and digestive juices flowing into the retroperitoneum. The wound should be closed as soon as possible after the lesion is removed. When a large volume of liquid has overflowed into the retroperitoneum, timely flushing and drainage can also reduce the incidence of infection. Besides, if the lesion is really difficult to remove endoscopically, timely conversion to surgery or laparoscopic-assisted resection may be a wiser option.

In addition, it should be noted that the duodenal lumen is relatively narrow, especially in the de

The present study was associated with some limitations. First, this was a single center retrospective study with a relatively small sample size, and a selection bias may have been present. Second, there was a lack of randomized and controlled samples. Third, the follow-up period of some cases was relatively short.

Endoscopic resection for duodenal GISTs appears to be effective and safe in selected cases. The pro

Currently, endoscopic resection of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) is a challenging procedure with a high risk of complications.

Traditional surgical treatment methods for duodenal GISTs are traumatic and prone to serious complications. Endoscopic resection of duodenal GISTs is an alternative. However, there are few reports on endoscopic treatment for duodenal GISTs.

We aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of endoscopic resection for duodenal GISTs.

This was a retrospective study. We collected data of 11 consecutive patients with duodenal GISTs who were treated with endoscopic resection and analyzed the rate of complete resection, bleeding, perforation, postoperative infection, recurrence, and distant metastasis.

All lesions were completely resected, while three cases (27.3%) had suspected positive margins. No local recurrence or distant metastasis were detected during the follow-up period in any of the patients.

Endoscopic resection for duodenal GISTs appears to be an effective and safe treatment by an ex

We need to expand the sample size to further confirm the effectiveness and safety of endoscopic re

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nishida T, Japan; Vij M, India; Weerasinghe KD, Sri Lanka S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Kallen ME, Hornick JL. The 2020 WHO Classification: What's New in Soft Tissue Tumor Pathology? Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45:e1-e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:70-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1244] [Cited by in RCA: 1300] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 3. | Deprez PH, Moons LMG, OʼToole D, Gincul R, Seicean A, Pimentel-Nunes P, Fernández-Esparrach G, Polkowski M, Vieth M, Borbath I, Moreels TG, Nieveen van Dijkum E, Blay JY, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic management of subepithelial lesions including neuroendocrine neoplasms: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2022;54:412-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 64.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Song JH, Kim SG, Chung SJ, Kang HY, Yang SY, Kim YS. Risk of progression for incidental small subepithelial tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 2015;47:675-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kushnir VM, Keswani RN, Hollander TG, Kohlmeier C, Mullady DK, Azar RR, Murad FM, Komanduri S, Edmundowicz SA, Early DS. Compliance with surveillance recommendations for foregut subepithelial tumors is poor: results of a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1378-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Landi B, Blay JY, Bonvalot S, Brasseur M, Coindre JM, Emile JF, Hautefeuille V, Honore C, Lartigau E, Mantion G, Pracht M, Le Cesne A, Ducreux M, Bouche O; «Thésaurus National de Cancérologie Digestive (TNCD)» (Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD); Fédération Nationale de Centres de Lutte Contre les Cancers (UNICANCER); Groupe Coopérateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie (GERCOR); Société Française de Chirurgie Digestive (SFCD); Société Française de Radiothérapie Oncologique (SFRO); Société Française d’Endoscopie Digestive (SFED); Société Nationale Française de Gastroentérologie (SNFGE). Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs): French Intergroup Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatments and follow-up (SNFGE, FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO). Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:1223-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bovee JVMG, Brodowicz T, Broto JM, Buonadonna A, De Álava E, Dei Tos AP, Del Muro XG, Dileo P, Eriksson M, Fedenko A, Ferraresi V, Ferrari A, Ferrari S, Frezza AM, Gasperoni S, Gelderblom H, Gil T, Grignani G, Gronchi A, Haas RL, Hassan B, Hohenberger P, Issels R, Joensuu H, Jones RL, Judson I, Jutte P, Kaal S, Kasper B, Kopeckova K, Krákorová DA, Le Cesne A, Lugowska I, Merimsky O, Montemurro M, Pantaleo MA, Piana R, Picci P, Piperno-Neumann S, Pousa AL, Reichardt P, Robinson MH, Rutkowski P, Safwat AA, Schöffski P, Sleijfer S, Stacchiotti S, Sundby Hall K, Unk M, Van Coevorden F, van der Graaf WTA, Whelan J, Wardelmann E, Zaikova O, Blay JY; ESMO Guidelines Committee and EURACAN. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv68-iv78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Nishida T, Hirota S, Yanagisawa A, Sugino Y, Minami M, Yamamura Y, Otani Y, Shimada Y, Takahashi F, Kubota T; GIST Guideline Subcommittee. Clinical practice guidelines for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in Japan: English version. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:416-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li J, Ye Y, Wang J, Zhang B, Qin S, Shi Y, He Y, Liang X, Liu X, Zhou Y, Wu X, Zhang X, Wang M, Gao Z, Lin T, Cao H, Shen L; Chinese Society Of Clinical Oncology Csco Expert Committee On Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Chinese consensus guidelines for diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Chin J Cancer Res. 2017;29:281-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Chung JC, Chu CW, Cho GS, Shin EJ, Lim CW, Kim HC, Song OP. Management and outcome of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the duodenum. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:880-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chok AY, Koh YX, Ow MY, Allen JC, Jr, Goh BK. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing pancreaticoduodenectomy vs limited resection for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(11):3429-3438.. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ren Z, Lin SL, Zhou PH, Cai SL, Qi ZP, Li J, Yao LQ. Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) without laparoscopic assistance for nonampullary duodenal subepithelial lesions: our clinical experience of 32 cases. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:3605-3611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yuan XL, Liu XW, Hu B. Endoscopic full-thickness resection for a duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2019;20:211-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1411-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 862] [Article Influence: 50.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ye LP, Zhang Y, Luo DH, Mao XL, Zheng HH, Zhou XB, Zhu LH. Safety of Endoscopic Resection for Upper Gastrointestinal Subepithelial Tumors Originating from the Muscularis Propria Layer: An Analysis of 733 Tumors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:788-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tsujii Y, Nishida T, Nishiyama O, Yamamoto K, Kawai N, Yamaguchi S, Yamada T, Yoshio T, Kitamura S, Nakamura T, Nishihara A, Ogiyama H, Nakahara M, Komori M, Kato M, Hayashi Y, Shinzaki S, Iijima H, Michida T, Tsujii M, Takehara T. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Endoscopy. 2015;47:775-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Tomizawa Y, Iyer PG, Wong Kee Song LM, Buttar NS, Lutzke LS, Wang KK. Safety of endoscopic mucosal resection for Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1440-7; quiz 1448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lépilliez V, Chemaly M, Ponchon T, Napoleon B, Saurin JC. Endoscopic resection of sporadic duodenal adenomas: an efficient technique with a substantial risk of delayed bleeding. Endoscopy. 2008;40:806-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gronchi A, Bonvalot S, Poveda Velasco A, Kotasek D, Rutkowski P, Hohenberger P, Fumagalli E, Judson IR, Italiano A, Gelderblom HJ, van Coevorden F, Penel N, Kopp HG, Duffaud F, Goldstein D, Broto JM, Wardelmann E, Marréaud S, Smithers M, Le Cesne A, Zaffaroni F, Litière S, Blay JY, Casali PG. Quality of Surgery and Outcome in Localized Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors Treated Within an International Intergroup Randomized Clinical Trial of Adjuvant Imatinib. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:e200397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hølmebakk T, Bjerkehagen B, Boye K, Bruland Ø, Stoldt S, Sundby Hall K. Definition and clinical significance of tumour rupture in gastrointestinal stromal tumours of the small intestine. Br J Surg. 2016;103:684-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McCarter MD, Antonescu CR, Ballman KV, Maki RG, Pisters PW, Demetri GD, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Brennan MF, McCall L, Ota DM, DeMatteo RP; American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Intergroup Adjuvant Gist Study Team. Microscopically positive margins for primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors: analysis of risk factors and tumor recurrence. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:53-9; discussion 59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang Y, Mao XL, Zhou XB, Yang H, Zhu LH, Chen G, Ye LP. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic resection for small (≤ 4.0 cm) gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3030-3037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Andalib I, Yeoun D, Reddy R, Xie S, Iqbal S. Endoscopic resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer in North America: methods and feasibility data. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:1787-1792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Singhal S, Changela K, Papafragkakis H, Anand S, Krishnaiah M, Duddempudi S. Over the scope clip: technique and expanding clinical applications. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:749-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mori H, Shintaro F, Kobara H, Nishiyama N, Rafiq K, Kobayashi M, Nakatsu T, Miichi N, Suzuki Y, Masaki T. Successful closing of duodenal ulcer after endoscopic submucosal dissection with over-the-scope clip to prevent delayed perforation. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:459-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Basford PJ, George R, Nixon E, Chaudhuri T, Mead R, Bhandari P. Endoscopic resection of sporadic duodenal adenomas: comparison of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) with hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) techniques and the risks of late delayed bleeding. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1594-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bartell N, Bittner K, Kaul V, Kothari TH, Kothari S. Clinical efficacy of the over-the-scope clip device: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:3495-3516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 28. | Wang ZZ, Zhou XB, Wang Y, Mao XL, Ye LP, Yan LL, Chen YH, Song YQ, Cai Y, Xu SW, Li SW. Effectiveness and safety of over-the-scope clip in closing perforations after duodenal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:5958-5966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Fujihara S, Mori H, Kobara H, Nishiyama N, Matsunaga T, Ayaki M, Yachida T, Masaki T. Management of a large mucosal defect after duodenal endoscopic resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6595-6609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chung J, Wang K, Podboy A, Gaddam S, K Lo S. Endoscopic Suturing for the Prevention and Treatment of Complications Associated with Endoscopic Mucosal Resection of Large Duodenal Adenomas. Clin Endosc. 2022;55:95-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ye LP, Mao XL, Zheng HH, Zhang Y, Shen LY, Zhou XB, Zhu LH. Safety of endoscopic resection for duodenal subepithelial lesions with wound closure using clips and an endoloop: an analysis of 68 cases. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:1070-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |