Published online Oct 16, 2022. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v14.i10.597

Peer-review started: July 17, 2022

First decision: August 19, 2022

Revised: September 1, 2022

Accepted: September 21, 2022

Article in press: September 21, 2022

Published online: October 16, 2022

Processing time: 86 Days and 10.7 Hours

Gastric cancer significantly contributes to cancer mortality globally. Gastric inte

To investigate factors associated with GIM development over time in African American-predominant study population.

This is a retrospective longitudinal study in a single tertiary hospital in Wash

Of 2375 patients who had at least 1 EGD with gastric biopsy, 579 patients were included in the study. 138 patients developed GIM during the study follow-up period of 1087 d on average, com

An increase in age and non-Caucasian race/ethnicity are associated with an increased risk of GIM formation. The effect of H. pylori on GIM is limited in low prevalence areas.

Core Tip: Gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM) is a precancerous lesion, and previous literature showed a higher rate in the United States minorities. Our study highlighted the natural history of GIM over time. It was observed in the study that irrespective of being minorities, Non-Caucasian races/ethnicities have a higher risk for GIM. Gastritis and older age contribute to GIM formation. The effect of Helicobacter pylori infection was not significant in our population.

- Citation: Ahmad AI, Lee A, Caplan C, Wikholm C, Pothoulakis I, Almothafer Z, Raval N, Marshall S, Mishra A, Hodgins N, Kang IG, Chang RK, Dailey Z, Daneshmand A, Kapadia A, Oh JH, Rodriguez B, Sehgal A, Sweeney M, Swisher CB, Childers DF, O'Connor C, Sequeira LM, Cho W. Gastric intestinal metaplasia development in African American predominant United States population. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2022; 14(10): 597-607

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v14/i10/597.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v14.i10.597

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer mortality world

The Correa cascade proposed that intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma is formed from normal gastric mucosa that progresses through a series of transition stages: Chronic gastritis, atrophic gastritis, gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM), and dysplasia, which can progress to gastric adenocarcinoma[5,6]. The latter three histopathological findings are considered as gastric premalignant lesions. GIM is defined as the replacement of normal gastric epithelium with intestinal epithelium consisting of Paneth, goblet, and absorptive cells[7]. The replacement happens under chronic stressors like inflammation. The prevalence of GIM in the general United States population is estimated to be 5%-8%[7] with an 0.13%–0.25%[6,7] estimated annual risk of progression into gastric cancer and a median time to progression of around 6 years[6].

Currently, GIM is more recognized as the best pre-malignant stage for surveillance because identifying and treating these lesions can potentially prevent further progression to gastric cancer[2,5]. Multiple international guidelines recommend surveillance for gastric pre-malignant lesions including GIM[8,9]; on the contrary, the American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) recommends against such screening guidelines for GIM with some exceptions[2]. Multiple risk factors have been identified to help guide surveillance including smoking, alcohol use, ethnicity, family history of gastric cancer, and genetic factors[10]. However, long-term effect of surveillance is not well understood in countries with a low incidence of gastric cancer due to the limitation of the available studies. Furthermore, the lack of clear guidelines for GIM medical management after diagnosis has added to the challenge[2]. Thus, we designed this retrospective longitudinal study to investigate potential risk factors involved in GIM formation from normal mucosa in an African American predominant United States population.

This is a retrospective longitudinal study conducted at Medstar Washington Hospital Center. The study was reviewed and approved by the Medstar Health Research Institute and Georgetown University Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Patients with GIM were identified from the Pathology Department’s database at Medstar Washington Hospital Center. Patients included in the study had undergone two or more esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs) with gastric biopsy, with at least one EGD performed between January 2015 to December 2020. Exclusion criteria consisted of patients age < 18, pregnancy, previous diagnosis of gastric cancer, and missing data including pathology results or endoscopy reports. Patients with a baseline of no GIM were followed up longitudinally. The follow-up period ended at the event occ

Electronic medical records were reviewed to collect and analyze the following patient information: Demographics, medication use, EGDs findings, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) status, gastric biopsy reports, and laboratory findings. Patients’ H. pylori statuses were exclusively based on biopsy testing.

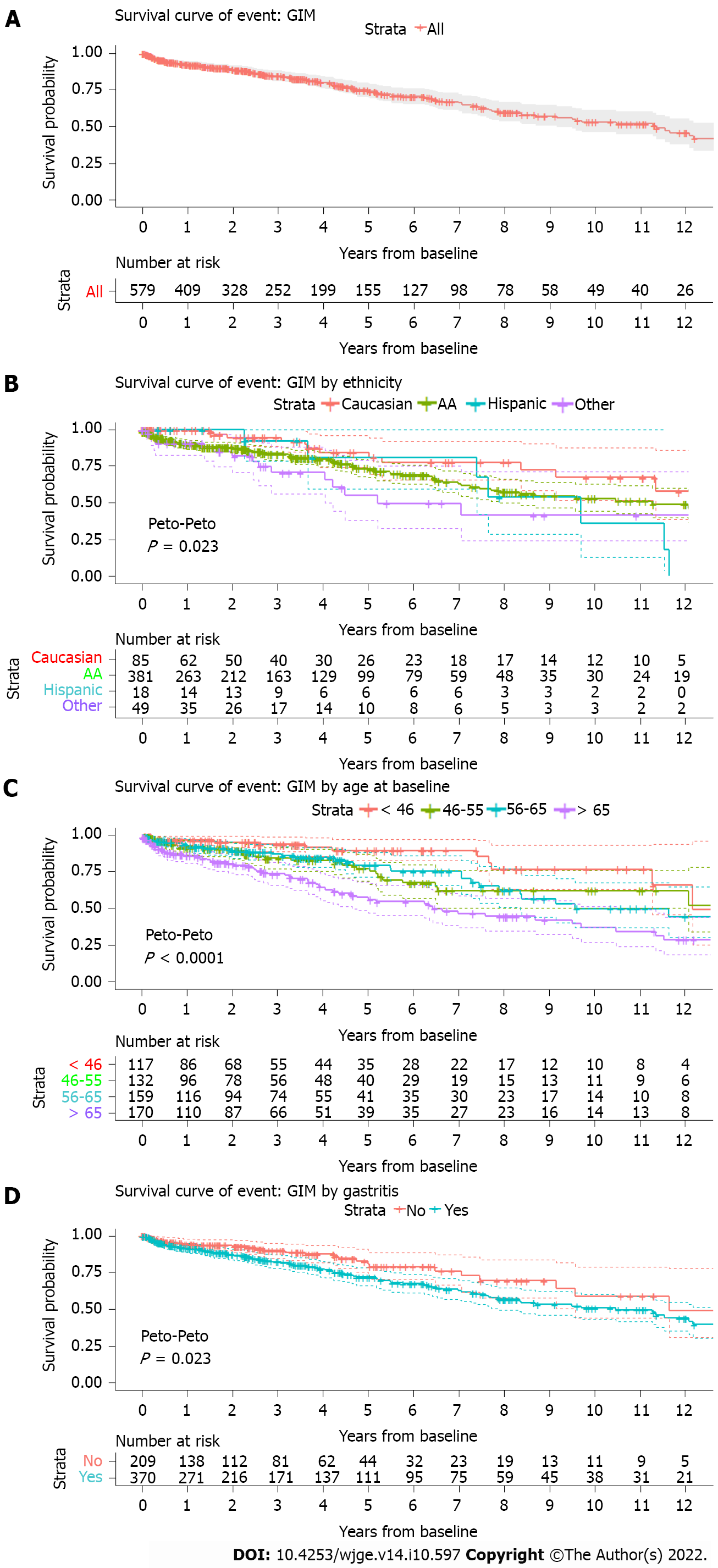

To present the data, we used frequency with percentage for categorical variables and median with first and third quartile (IQR) for non-normal continuous variables. The D'Agostino-Pearson test was used to test normality. Chi-square test with Yate’s correction or Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test was performed to compare the difference between the groups. Kaplan-Meier estimators were calculated, and the curves were plotted to show the probability of GIM at a respective time interval after the baseline. To detect the differences in survival, we used Peto-Peto's weighted Log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was performed to investigate how the predictors were associated with the risk of GIM over time. All unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios with 95 percent confidence intervals were presented, along with the unadjusted P values. Statistical significance was set at a P value less than 0.05 and all statistical analyses were conducted with R software. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Jiling Chou from MedStar Health Research institute.

Of 2375 patients who had at least 1 EGD with gastric biopsy during 2015 to 2020, 579 patients met our inclusion criteria. A total of 138 (23.8%) patients developed GIM during the follow-up period of 1087 days on average, compared to 857 d in patients without GIM (P = 0.247). The GIM group was older with an average age of 64 years compared to 56 years in the non-GIM group (P < 0.001). Female patients represented 60.7% (351 patients) of the total study population and there was not a significant difference between study groups (P = 0.208). Ethnicity was significantly different between the study groups (P = 0.032): African American, Caucasian, Hispanic and other ethnicities/races represented 72.9% (94 patients), 9.3% (12 patients), 5.4% (7 patients), and 12.4% (16 patients) of the GIM group respectively, compared to 71% (287 patients), 18.1% (73 patients), 2.7% (11 patients), and 8.2% (33 patients) in the non-GIM group respectively (Table 1).

| Level | Baseline no GIM | ||||

| Overall | No GIM | GIM | P value | ||

| 579 | 441 | 138 | |||

| Follow-up days [median (IQR)] | 885.0 (257.5, 1901.5) | 857.0 (259.0, 1834.0) | 1087.0 (260.5, 2307.3) | 0.247 | |

| Age baseline [median (IQR)] | 58.0 (49.0, 67.8) | 56.0 (46.8, 65.0) | 64.00 (54.0, 72.0) | < 0.001 | |

| Sex (%) | Male | 227 (39.3) | 166 (37.7) | 61 (44.2) | 0.208 |

| Female | 351 (60.7) | 274 (62.3) | 77 (55.8) | ||

| Ethnicity/Race (%) | Caucasian | 85 (15.9) | 73 (18.1) | 12 ( 9.3) | 0.032 |

| AA | 381 (71.5) | 287 (71.0) | 94 (72.9) | ||

| Hispanic | 18 ( 3.4) | 11 ( 2.7) | 7 ( 5.4) | ||

| Other | 49 ( 9.2) | 33 ( 8.2) | 16 (12.4) | ||

| Obesity (%) | BMI < 30 | 261 (56.7) | 191 (53.5) | 70 (68.0) | 0.013 |

| BMI > 30 | 199 (43.3) | 166 (46.5) | 33 (32.0) | ||

| Smoking status (%) | Never | 269 (54.8) | 207 (55.3) | 62 (53.0) | 0.198 |

| Previous | 119 (24.2) | 84 (22.5) | 35 (29.9) | ||

| Current | 103 (21.0) | 83 (22.2) | 20 (17.1) | ||

| Biopsy site (%) | ≤ 2 | 227 (39.2) | 190 (43.1) | 37 (26.8) | 0.001 |

| > 3 | 352 (60.8) | 251 (56.9) | 101 (73.2) | ||

| H. pylori at Baseline (%) | No | 499 (86.2) | 382 (86.6) | 117 (84.8) | 0.686 |

| Yes | 80 (13.8) | 59 (13.4) | 21 (15.2) | ||

| H. pylori at follow-up (%) | No | 536 (92.6) | 413 (93.7) | 123 (89.1) | 0.114 |

| Yes | 43 ( 7.4) | 28 ( 6.3) | 15 (10.9) | ||

| n | 80 | 59 | 21 | ||

| H. pylori at follow up with positive Baseline (%) | No | 65 (81.2) | 48 (81.4) | 17 (81.0) | 1 |

| Yes | 15 (18.8) | 11 (18.6) | 4 (19.0) | ||

| Gastritis (%) | No | 209 (36.1) | 180 (40.8) | 29 (21.0) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 370 (63.9) | 261 (59.2) | 109 (79.0) | ||

| Ulcer (%) | No | 534 (92.2) | 408 (92.5) | 126 (91.3) | 0.778 |

| Yes | 45 ( 7.8) | 33 ( 7.5) | 12 ( 8.7) | ||

| 81 mg Aspirin Use at Baseline (%) | No | 450 (77.7) | 347 (78.7) | 103 (74.6) | 0.379 |

| Yes | 129 (22.3) | 94 (21.3) | 35 (25.4) | ||

| 81 mg Aspirin use at follow up (%) | No | 453 (78.2) | 359 (81.4) | 94 (68.1) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 126 (21.8) | 82 (18.6) | 44 (31.9) | ||

| PPI usage at baseline (%) | No | 392 (67.7) | 285 (64.6) | 107 (77.5) | 0.006 |

| Yes | 187 (32.3) | 156 (35.4) | 31 (22.5) | ||

| PPI usage at follow up (%) | No | 318 (54.9) | 233 (52.8) | 85 (61.6) | 0.088 |

| Yes | 261 (45.1) | 208 (47.2) | 53 (38.4) | ||

| Blood type (%) | A | 72 (31.2) | 47 (28.7) | 25 (37.3) | 0.317 |

| B | 42 (18.2) | 28 (17.1) | 14 (20.9) | ||

| O | 109 (47.2) | 82 (50.0) | 27 (40.3) | ||

| AB | 8 ( 3.5) | 7 ( 4.3) | 1 ( 1.5) | ||

| Hemoglobin [median (IQR)] | 11.2 (9.2, 12.8) | 11.5 (9.5, 13.0) | 10.5 (9.0, 12.2) | 0.075 | |

| Hemoglobin Baseline [median (IQR)] | 10.8 (9.2, 12.8) | 11.8 (9.7, 13.1) | 9.60 (8.40, 11.00) | < 0.001 | |

Regarding medication use, a higher percentage of the GIM group [44 patients (31.9%)] was using 81 mg of aspirin on follow-up, compared to 82 patients (18.6%) in the non-GIM group (P = 0.001). A lower percentage of the GIM group [31 patients (22.5 %)] was using proton pump inhibitors (PPI) at baseline compared to 156 patients (35.4%) in the non-GIM group (P = 0.006). However, aspirin use at baseline and PPI use on follow up was not significantly different between study groups.

On follow-up EGDs, gastritis was observed more in the GIM group [109 patients (79.0 %)] compared to 261 patients (59.2%) with gastritis in the non-GIM group (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

H. pylori was positive in the baseline biopsies of 80 patients (13.2%), compared to those of 43 patients (7.4 %) on follow-up. Of this H. pylori positive group, 15 patients had positive H. pylori at both the baseline and follow-up, but this persistent H. pylori infection was not different between the two study groups. A detailed summary of the data is presented in Table 1.

In a group of patients with no GIM at baseline, adding one year in age increases the risk of GIM by 4% over time with a P value < 0.001. In comparison to the age group of 45 years or younger, patients have a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.13 (P = 0.028), 2.09 (P = 0.029), and 4.03 (P < 0.001) for age groups 46-55, 56-64, and ≥ 65 years respectively. Over time, African Americans, Hispanics, and other ethnicities/races had an increased risk of GIM compared to Caucasians with an HR of 2.12 (1.16, 3.87), 2.79 (1.09, 7.13), and 3.19 (1.5, 6.76) respectively. Gastritis on follow-up biopsy was associated with a higher risk of GIM with an HR of 1.62 (1.07, 2.44) (P = 0.022), while 81 mg aspirin use increased the risk of GIM by 49% (P = 0.031). Obesity at baseline had a 42% less risk of GIM (P = 0.010). Using the H. pylori-negative group at baseline and follow-up as a reference group, H. pylori infection at baseline or follow-up, as well as the persistence of H. pylori infection did not have significant effects on GIM risk over time. Subgroup analysis of patients with H. pylori present at baseline shows no major difference from the main study analysis (Table 2).

| Predictor | GIM | |

| HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.04 (1.02, 1.05) | < 0.001 |

| Age (ref: ≤ 45) | ||

| 46-55 | 2.13 (1.08, 4.19) | 0.028 |

| 56-65 | 2.09 (1.08, 4.03) | 0.029 |

| > 65 | 4.03 (2.17, 7.48) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 0.81 (0.58, 1.14) | 0.229 |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref: Caucasians) | ||

| African American | 2.12 (1.16, 3.87) | 0.015 |

| Hispanic | 2.79 (1.09, 7.13) | 0.032 |

| Other | 3.19 (1.50, 6.76) | 0.003 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | 0.58 (0.38, 0.88) | 0.010 |

| Gastritis | 1.62 (1.07, 2.44) | 0.022 |

| H. pylori (ref: Baseline: Neg, follow-up: Neg) | ||

| Baseline: Neg, follow-up: Pos | 0.88 (0.45, 1.7) | 0.695 |

| Baseline: Pos, follow-up: Neg | 1.16 (0.7, 1.94) | 0.563 |

| Baseline: Pos, follow-up: Pos | 1.02 (0.37, 2.8) | 0.966 |

| PPI Usage at follow-up | 0.81 (0.57, 1.14) | 0.225 |

| PPI Usage Baseline | 0.80 (0.54, 1.20) | 0.280 |

| Aspirin Use at follow-up (81 mg) | 1.49 (1.04, 2.14) | 0.031 |

| Aspirin Use Baseline (81 mg) | 1.45 (0.98, 2.13) | 0.063 |

| Smoking status (ref: Never) | ||

| Previous smoker | 1.35 (0.89, 2.04) | 0.161 |

| Current smoker | 1.01 (0.61, 1.68) | 0.972 |

| Blood group (ref: Group A) | ||

| Blood group B | 1.07 (0.56, 2.07) | 0.835 |

| Blood group O | 0.66 (0.38, 1.14) | 0.135 |

| Blood group AB | 0.24 (0.03, 1.77) | 0.161 |

| Haemoglobin level at follow-up | 1.00 (0.92, 1.09) | 0.962 |

| Haemoglobin level at baseline | 0.83 (0.74, 0.93) | 0.001 |

On multivariate Cox regression analysis, the age ≥ 65 group was continuously associated with a higher risk of GIM with an HR of 3.01 (P = 0.014). African Americans and other ethnicities have a higher risk of GIM with an HR of 3.4 (P = 0.026) and 7.46 (P = 0.001) when compared to Caucasians res

| HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age at baseline (ref: ≤ 45) | ||

| 46-55 | 1.75 (0.67, 4.58) | 0.255 |

| 56-65 | 1.44 (0.56, 3.68) | 0.445 |

| > 65 | 3.01 (1.25, 7.26) | 0.014 |

| Female | 0.8 (0.48, 1.33) | 0.384 |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref: Caucasians) | ||

| African American | 3.4 (1.16, 9.95) | 0.026 |

| Hispanic | 1.64 (0.28, 9.47) | 0.582 |

| Other | 7.46 (2.26, 24.67) | 0.001 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | 0.71 (0.42, 1.2) | 0.201 |

| Gastritis | 1.65 (0.97, 2.81) | 0.065 |

| H. pylori (ref: Baseline: Neg, follow-up: Neg) | ||

| Baseline: Neg, follow-up: Pos | 1.26 (0.53, 2.98) | 0.602 |

| Baseline: Pos, follow-up: Neg | 0.6 (0.26, 1.37) | 0.223 |

| Baseline: Pos, follow-up: Pos | 1.13 (0.34, 3.76) | 0.847 |

| Smoking (ref: Never) | ||

| Previous | 0.96 (0.56, 1.65) | 0.876 |

| Current | 0.74 (0.38, 1.47) | 0.398 |

We calculated the Kaplan-Meier survival estimate for GIM development over 12 years. The popu

GIM is a recognized gastric pre-malignant lesion with an increased risk for developing gastric cancer. The risk factors for GIM formation and evolution are significant clinical interest and thus currently under active investigation since these factors will likely help design optimal surveillance programs and management of GIM after diagnosis. Our study showed that the GIM group was older compared to the non-GIM group (Table 1). In multiple studies including ours, more advanced age was associated with an increased risk of GIM formation, progression, and gastric cancer development, which could be attributable to prolonged exposure of gastric mucosa to mutagenic factors and inflammation[1,4,11]. The average age at GIM diagnosis in low gastric cancer incident countries was 60 to 67 years, comparable to the average age of 64 in our GIM group (Table 1)[1,11,12]. A one-year increase in age was associated with a 4% increase in GIM risk in our population. Age groups of 45-54, 55-64, and > 65 were associated with an increased risk for GIM development compared to the < 45 age group (Table 2). The age group > 65 had the highest HR, and it was the only age group associated with an increased risk of GIM form

Although gastric cancer is known to be more common in males[14], GIM has equally affected both genders in our study and others[1,4]. In contrast, a cohort study in Puerto Rico showed a greater percentage of females affected by GIM compared to males[12], and in a Thai population, the male sex was a risk factor for GIM development[11]. The influence of gender on GIM development might be significant, but our study might have failed to detect it due to the small sample size. Alternatively, gender might have an isolated effect on GIM progression to gastric cancer rather than GIM development.

Non-cardia gastric cancer has a higher incidence rate in certain United States race/ethnicity min

Currently, the AGA recommends surveillance for ethnic/racial minorities only on a conditional basis[2]. Place of birth, rather than ethnicity, was shown to be a risk factor for GIM in one study, where only Hispanics born outside the United States carry a higher risk for GIM compared to Hispanics born in the United States regardless of H. pylori status[19]. The effect of place of birth and race on GIM needs further investigation, as it might be a potential factor that affects surveillance.

The impact of H. pylori infection on GIM formation and progression was extensively investigated, but the results in the literature were often conflicting thus suggesting the complex role of H. pylori in GIM and gastric cancer. H. pylori infection is thought to affect the development and progression of GIM[20], but few studies have shown either formation or progression but not both[17]. Ethnicity, genetic makeup, and H. pylori virulence factors are additional factors that can further influence the effect of H. pylori on GIM[10,18,21]. However, in the present study, no clear effect of H. pylori on GIM development was found as shown in other studies[4,19,22]. In our study population, only 13.8% of patients had H. pylori infection, which is lower than the reported average H. pylori infection in the United States and patients with positive H. pylori infection at baseline biopsy, follow-up biopsy, or both seem to have the same risk of developing GIM, not different from those who tested negative for H. pylori. However, given the known strong association between H. pylori and gastric cancer, we agree with the AGA recommendation for testing and treating H. pylori and confirming its eradication, especially if positive in GIM, even though our results did not show a direct effect of H. pylori on GIM formation.

Chronic gastritis is part of the Correa cascade, and it precedes GIM development. The long-term effect of H. pylori-negative chronic gastritis and its role in the development of GIM have been poorly studied. A prospective study in Thailand investigated 400 patients with chronic gastritis and showed that chronic gastritis is associated with an increased risk for progression regardless of H. pylori status[4]. Our study showed that gastritis is associated with GIM formation over time. The gastric inflammation, rather than the H. pylori infection itself, might be driving GIM formation. On the 12 years survival curve, a significant difference in GIM formation is shown between the group with and without gastritis, noticeable as early as 1 year (Figure 1D). Thus, early recognition and treatment of gastritis can impact GIM formation and possibly prevent GIM thus reducing gastric cancer risk.

The study is limited by its retrospective nature. All the patients in the study are from a single tertiary center in Washington, DC. The standard evaluation of GIM in our pathology lab does not involve further grading or classification, which added to the study's limitation. In spite of the retrospective nature of the study, the strength of our study is its unique study design and distinct study population to assess the longitudinal data over time between upper endoscopies in a single academic center with a predominantly African American population, which has not been adequately investigated in other studies. It is also notable that this study population has a low prevalence of H. pylori, thus allowing us to examine other risk factors involved in the development of GIM aside from H. pylori infection. Our limitations also include the low number of Asians in our study population who were included as the other ethnic/racial category in our study, thus limiting comparisons with other published studies from Asia.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that race is an important risk factor for GIM and ethnic/racial minorities in the United States carry a higher risk of GIM compared to Caucasians. Older age, especially age group > 65, was associated with higher GIM risk. Gastritis rather than H. pylori infection is also associated with GIM formation in our low H. pylori prevalent patient population. These risk factors identified in our study will serve as important components in developing risk stratification models for optimal surveillance programs for GIM and gastric cancer.

Gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM) is a form of gastric pre-malignant lesions. It falls on the spectrum of the Correa cascade. The cascade includes chronic gastritis, atrophic gastritis, GIM, and dysplasia.

We designed this study to investigate factors leading to GIM formation. There is a lack of literature about this topic in the United States, especially among ethnic minorities, which are considered high-risk populations.

We aimed to identify factors that increase GIM formation in high-risk populations. These factors would help guide the future surveillance of selected patients and possibly suggest treatment modalities.

This is a retrospective longitudinal study in a tertiary hospital in Washington, DC. The study includes patients with at least two upper endoscopies with gastric biopsies to assess the evolution of GIM over time. A Cox regression model was built to investigate the significant factors over the study time.

Our study confirms that Ethnicity-Race minorities have a higher rate of GIM formation. We found that gastritis increases GIM formation over time. Helicobacter pylori in low-prevalence areas might not be a strong risk factor. Our results emphasize on future surveillance of minorities and management of gastritis as a way to reduce the burden of gastric cancer.

In conclusion, our study suggests that older age, having gastritis, or being from ethnic-race minorities is associated with an increased risk of GIM.

Further studies are needed to clarify factors associated with GIM progression and regression. This would help form a complete picture of the development and progression of gastric pre-malignant lesions.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gingold-Belfer R, Israel; Li XB, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Lee JWJ, Zhu F, Srivastava S, Tsao SK, Khor C, Ho KY, Fock KM, Lim WC, Ang TL, Chow WC, So JBY, Koh CJ, Chua SJ, Wong ASY, Rao J, Lim LG, Ling KL, Chia CK, Ooi CJ, Rajnakova A, Yap WM, Salto-Tellez M, Ho B, Soong R, Chia KS, Teo YY, Teh M, Yeoh KG. Severity of gastric intestinal metaplasia predicts the risk of gastric cancer: a prospective multicentre cohort study (GCEP). Gut. 2022;71:854-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gupta S, Li D, El Serag HB, Davitkov P, Altayar O, Sultan S, Falck-Ytter Y, Mustafa RA. AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on Management of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:693-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11573] [Cited by in RCA: 13167] [Article Influence: 1881.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Aumpan N, Vilaichone RK, Pornthisarn B, Chonprasertsuk S, Siramolpiwat S, Bhanthumkomol P, Nunanan P, Issariyakulkarn N, Ratana-Amornpin S, Miftahussurur M, Mahachai V, Yamaoka Y. Predictors for regression and progression of intestinal metaplasia (IM): A large population-based study from low prevalence area of gastric cancer (IM-predictor trial). PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Correa P. Gastric cancer: overview. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:211-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Huang KK, Ramnarayanan K, Zhu F, Srivastava S, Xu C, Tan ALK, Lee M, Tay S, Das K, Xing M, Fatehullah A, Alkaff SMF, Lim TKH, Lee J, Ho KY, Rozen SG, Teh BT, Barker N, Chia CK, Khor C, Ooi CJ, Fock KM, So J, Lim WC, Ling KL, Ang TL, Wong A, Rao J, Rajnakova A, Lim LG, Yap WM, Teh M, Yeoh KG, Tan P. Genomic and Epigenomic Profiling of High-Risk Intestinal Metaplasia Reveals Molecular Determinants of Progression to Gastric Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:137-150.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Huang RJ, Choi AY, Truong CD, Yeh MM, Hwang JH. Diagnosis and Management of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia: Current Status and Future Directions. Gut Liver. 2019;13:596-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Banks M, Graham D, Jansen M, Gotoda T, Coda S, di Pietro M, Uedo N, Bhandari P, Pritchard DM, Kuipers EJ, Rodriguez-Justo M, Novelli MR, Ragunath K, Shepherd N, Dinis-Ribeiro M. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients at risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2019;68:1545-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 68.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Marcos-Pinto R, Areia M, Leja M, Esposito G, Garrido M, Kikuste I, Megraud F, Matysiak-Budnik T, Annibale B, Dumonceau JM, Barros R, Fléjou JF, Carneiro F, van Hooft JE, Kuipers EJ, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:365-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 712] [Cited by in RCA: 672] [Article Influence: 112.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nieuwenburg SAV, Mommersteeg MC, Eikenboom EL, Yu B, den Hollander WJ, Holster IL, den Hoed CM, Capelle LG, Tang TJ, Anten MP, Prytz-Berset I, Witteman EM, Ter Borg F, Burger JPW, Bruno MJ, Fuhler GM, Peppelenbosch MP, Doukas M, Kuipers EJ, Spaander MCW. Factors associated with the progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia: a multicenter, prospective cohort study. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E297-E305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aumpan N, Vilaichone RK, Nunanan P, Chonprasertsuk S, Siramolpiwat S, Bhanthumkomol P, Pornthisarn B, Uchida T, Vilaichone V, Wongcha-Um A, Yamaoka Y, Mahachai V. Predictors for development of complete and incomplete intestinal metaplasia (IM) associated with H. pylori infection: A large-scale study from low prevalence area of gastric cancer (IM-HP trial). PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cruz-Cruz JJ, González-Pons M, Cora-Morges A, Soto-Salgado M, Colón G, Alicea K, Rosado K, Morgan DR, Cruz-Correa M. Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia: Demographic and Epidemiological Characterization in Puerto Rican Hispanics (2012-2014). Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2021;2021:9806156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Leung WK, Lin SR, Ching JY, To KF, Ng EK, Chan FK, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Factors predicting progression of gastric intestinal metaplasia: results of a randomised trial on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gut. 2004;53:1244-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lou L, Wang L, Zhang Y, Chen G, Lin L, Jin X, Huang Y, Chen J. Sex difference in incidence of gastric cancer: an international comparative study based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e033323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gupta S, Tao L, Murphy JD, Camargo MC, Oren E, Valasek MA, Gomez SL, Martinez ME. Race/Ethnicity-, Socioeconomic Status-, and Anatomic Subsite-Specific Risks for Gastric Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:59-62.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nguyen TH, Tan MC, Liu Y, Rugge M, Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Prevalence of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia in a Multiethnic US Veterans Population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:269-276.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Huang RJ, Ende AR, Singla A, Higa JT, Choi AY, Lee AB, Whang SG, Gravelle K, D'Andrea S, Bang SJ, Schmidt RA, Yeh MM, Hwang JH. Prevalence, risk factors, and surveillance patterns for gastric intestinal metaplasia among patients undergoing upper endoscopy with biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:70-77.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fennerty MB, Emerson JC, Sampliner RE, McGee DL, Hixson LJ, Garewal HS. Gastric intestinal metaplasia in ethnic groups in the southwestern United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1992;1:293-296. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Tan MC, Jamali T, Nguyen TH, Galvan A, Sealock RJ, Khan A, Zarrin-Khameh N, Holloman A, Kampagianni O, Ticas DH, Liu Y, El-Serag HB, Thrift AP. Race/Ethnicity and Birthplace as Risk Factors for Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia in a Multiethnic United States Population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:280-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhou L, Sung JJ, Lin S, Jin Z, Ding S, Huang X, Xia Z, Guo H, Liu J, Chao W. A five-year follow-up study on the pathological changes of gastric mucosa after H. pylori eradication. Chin Med J (Engl). 2003;116:11-14. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Pilotto A, Rassu M, Bozzola L, Leandro G, Franceschi M, Furlan F, Meli S, Scagnelli M, Di Mario F, Valerio G. Cytotoxin-associated gene A-positive Helicobacter pylori infection in the elderly. Association with gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;26:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Almouradi T, Hiatt T, Attar B. Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia in an Underserved Population in the USA: Prevalence, Epidemiologic and Clinical Features. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:856256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |