Published online Apr 16, 2020. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v12.i4.128

Peer-review started: December 28, 2019

First decision: January 13, 2020

Revised: January 24, 2020

Accepted: March 22, 2020

Article in press: March 22, 2020

Published online: April 16, 2020

Processing time: 104 Days and 1.2 Hours

It is important to reduce patient discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Remedial measures can be taken to alleviate discomfort if the causative factors are determined; however, all the factors have not been elucidated yet.

To clearly determine the factors influencing discomfort in transoral esophagogastroduodenoscopy using a large-size cross-sectional study with readily available data.

Consecutive patients who underwent screening transoral esophagogastroduodenoscopy consecutively between August 2017 and October 2017 at a health check-up center were included. Discomfort was evaluated using a face scale between 0 and 10 with a 6-level questionnaire. Univariate and multiple regression analyses were performed to investigate the factors related to the discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Univariate analysis was performed in both the unsedated and sedated study groups. Age, sex, height, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol intake, hiatal hernia, history of gastrectomy, biopsy during examination, Lugol’s solution usage, administration of butylscopolamine with/without a sedative (pethidine, midazolam, or both), endoscope model, history of endoscopy, and endoscopists were considered as possible factors of discomfort.

Finally, 1715 patients were enrolled in this study. Overall, the median discomfort score was 2 and the interquartile range was 2-4. High discomfort (score ≥ 6) was recorded in 18% of the participants. According to univariate analysis, in the unsedated group, young age (P < 0.001), female sex (P < 0.001), and no history of endoscopy (P < 0.001) were factors associated with increased discomfort. Significant differences were also noted for height (P = 0.007), smoking status (P = 0.003), and endoscopists (P < 0.001). In the sedation group, young age (P < 0.001), female sex (P < 0.001), and no history of endoscopy (P = 0.004) were associated with increased discomfort; additionally, significant differences were found in smoking status (P < 0.001), type of sedation (P < 0.001), and endoscopists (P = 0.027). There was also a marginal difference due to alcohol intake (P = 0.055). Based on multiple regression analysis, young age, female sex, less height, current smoking status, and presence of hiatal hernia [regression coefficients of 0.08, P < 0.001 (for -1 years); 0.45, P = 0.013; 0.02, P = 0.024 (for -1 cm); 0.35, P = 0.036; and 0.34, P = 0.003, respectively] were factors that significantly increased discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Alternatively, sedation significantly reduced discomfort and pethidine (regression coefficient: -1.47, P < 0.001) and midazolam (regression coefficient: -1.63, P = 0.001) significantly reduced the discomfort both individually and in combination (regression coefficient: -2.92, P < 0.001). A difference in the endoscopist performing the procedure was also associated with discomfort.

Young age, female sex, and smoking are associated with esophagogastroduodenoscopy discomfort. Additionally, heavy alcohol consumption diminished the effects of sedation. These factors are easily obtained and are thus useful.

Core tip: It is essential to reduce discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy. The present study clearly identified the factors associated with discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy using a large-size cross-sectional study. Young age, female sex, and current smoking were identified as the contributive factors. Smoking status was a newly identified predictor of this study. Furthermore, heavy alcohol consumption was noted to diminish the effect of the sedative(s). These factors are useful because they can be easily obtained, and we can take remedial measures for reducing discomfort.

- Citation: Majima K, Shimamoto T, Muraki Y. Causative factors of discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy: A large-scale cross-sectional study. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2020; 12(4): 128-137

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v12/i4/128.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v12.i4.128

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy often causes discomfort in patients. Discomfort due to the endoscope contributes to a negative experience and reduces the patient’s satisfaction[1,2]. Therefore, it is important to reduce discomfort as much as possible. Sedation is mainly considered as a method to reduce such discomfort; however, due to the cost and risk of complications, the consensus is to perform endoscopy without sedation in appropriately selected patients[3]. To identify the patients who are likely to have marked discomfort, so that they can be considered for sedation, the predictive factors of discomfort must be ascertained. In previous studies, young age[4-7], female sex[4,5,8,9], anxiety before the examination[4,5,6,9], and pharyngeal sensitivity[6,7] were identified as factors that increased the discomfort of transoral esophagogastroduodenoscopy; however, all factors have not yet been elucidated. Most previous studies have conducted investigations only in several hundred subjects, which is a relatively small sample. The aim of this study was to elucidate the contributing factors of discomfort in transoral esophagogastroduodenoscopy by a large-scale cross-sectional study, using easily available information from a regular endoscopy examination practice.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kameda Medical Center. Since this was a retrospective observational study, using already existing data, and did not include invasive interventions, the requirement for informed consent from the study participants was waived by the Institutional Review Board. However, written informed consent for endoscopy was obtained at the time of the procedure. The study protocol was published on the hospital’s website. This study’s methods are in accordance with the Japanese “Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects”.

All consecutive patients who had undergone screening transoral esophagogastroduodenoscopy at a health check-up center associated with a general hospital between August 2017 and October 2017 were included. The discomfort experienced by the patients during examination was evaluated using a questionnaire subsequent to either completion of the examination or recovery from sedation. Originally, the questionnaires were intended for the improvement of hospital services to the patients; the questionnaire results and medical records of the patients were utilized for this study. Accordingly, participants with inadequate responses in the questionnaire were excluded. In order to increase the statistical accuracy of this study, the data was collected from the largest sample size possible.

In preparation for endoscopy, dimethicone (Barugin antifoam solution; Kaigen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Osaka, Japan) containing pronase (PronaseMS; Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan) and sodium bicarbonate (Yoshida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan) were administered orally. For topical pharyngeal anesthesia, 8% lidocaine spray (Xylocaine Pump Spray 8%; Aspen Japan Co., Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan) was administered. The decision to administer an antispasmodic agent depended on the endoscopist; when administered, intravenous injection of 10 mg butylscopolamine (Scopolamine butylbromide; Nichi-Iko Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan) was used. Sedatives were administered upon the request of the patients and with the permission of the doctor; accordingly, an intravenous injection of pethidine (Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan) was predominantly used, sometimes in combination with midazolam (Sandoz Co., Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan); however, midazolam was rarely used alone. Sedation was induced prior to scope insertion. Patients expected to drive were not administered any sedatives, even upon request. The endoscope used either the GIF-PQ260, GIF-Q260, or GIF-H290 (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The number of endoscopists who conducted the examination was 27. The esophagus, stomach, and partial duodenum were endoscopically observed. The mouthpiece for endoscopic examination had a tube capable of aspirating saliva continuously.

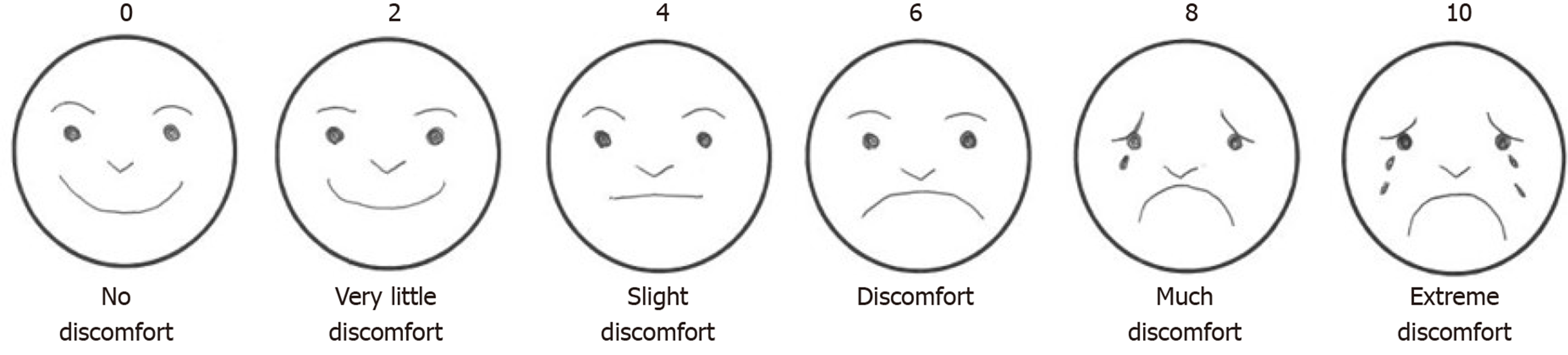

The questionnaire was distributed to the patients at a different location from the endoscopy unit, by staff other than the ones who performed the endoscopy. Discomfort was evaluated on a face scale of 0 to 10 on a 6-level questionnaire (Figure 1).

Since the discomfort scores had a non-normal distribution, the median and interquartile ranges were calculated for all cases. In addition, the proportion of high discomfort (score ≥ 6) was calculated. Age, sex, height, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol intake, hiatal hernia, history of gastrectomy, biopsy performed during examination, administration of Lugol’s solution, administration of butylscopolamine with/without a sedative (pethidine, midazolam, or both), endoscope model, history of endoscopy, and endoscopists were considered as probable factors of discomfort. Based on the smoking status to the participants were classified as current-smoker, past-smoker and non-smoker. Classification based on alcohol consumption included non-drinker, never to rare drinking; heavy drinker, ≥ 40 mg/d of alcohol for ≥ 3 d/wk; and the rest as normal drinker. GIF-Q260 and GIF-H290 with a diameter of 9.2 mm and 8.9 mm, respectively, defined as a normal diameter, and GIF-PQ260 with 7.9 mm, defined as a small diameter, were the endoscope models used. The participants were divided into subgroups: Sedated and non-sedated, which was expected to be strongly related to discomfort. The median discomfort score and the proportion of high discomfort (score ≥ 6) were calculated for each factor, and a univariate analysis was performed.

Furthermore, as an adjustment for bias, we implemented multiple regression analysis to clarify the factors associated with discomfort for the primary outcome. In this analysis, the objective variable was the discomfort score, and the explanatory variables were the probable factors relating to the discomfort.

In order to investigate the effect of heavy alcohol consumption on sedation, multiple regression analysis adjusted for the factors of discomfort was performed in the subgroups with and without sedation as an additional analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (ver1.37; Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

The number of participants were 1792. Seventy-seven patients were excluded due to inadequate questionnaire responses; finally, 1715 patients were enrolled in this study. Table 1 includes the demographics of all participants by possible factors relating to discomfort. We were able to obtain all the data for the factors without any gaps. Overall, the median discomfort score and the interquartile range were 2 and 2-4, respectively, and 18% of the participants had high discomfort levels (score ≥ 6).

| Possible factors relating to discomfort | Mean (SD) |

| Age | 59 (11) |

| BMI | 23.5 (3.6) |

| Height | 163.1 (8.8) |

| Possible factors relating to discomfort number (%) | |

| Age | |

| ≤ 39 | 80 (4.7) |

| 40-49 | 308 (18.0) |

| 50-59 | 431 (25.1) |

| 60-69 | 610 (35.6) |

| ≥ 70 | 286 (16.7) |

| Male sex | 950 (55%) |

| BMI ≥ 25 | 503 (29.3) |

| Height | |

| < 150 cm | 114 (6.7) |

| 150-160 cm | 546 (31.8) |

| 160-170 cm | 644 (37.6) |

| ≥ 170 cm | 411 (24.0) |

| Smoking status | |

| Non-smoker | 988 (57.6) |

| Past-smoker | 487 (28.4) |

| Current-smoker | 240 (14.0) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Non-drinker | 761 (44.4) |

| Normal drinker | 812 (47.4) |

| Heavy-drinker | 142 (8.3) |

| History of endoscopy | 1602 (93.4) |

| History of gastrectomy | 30 (1.8) |

| Butylscopolamine administration | 511 (29.8) |

| Biopsy performed | 49 (2.9) |

| Lugol’s solution use | 7 (0.4) |

| Small diameter endoscope | 1657 (96.6) |

| Hiatal hernia | 775 (45.2) |

| Sedative | |

| None | 774 (45.1) |

| Pethidine | 797 (46.5) |

| Midazolam | 19 (1.1) |

| Pethidine and midazolam | 125 (7.3) |

According to the univariate analysis in the non-sedated group, the factors associated with increased discomfort were young age (P < 0.001), female sex (P < 0.001), and no history of endoscopy (P < 0.001); additionally, significant differences were also found for height (P = 0.007), smoking status (P = 0.003), and endoscopist (P < 0.001) (Table 2). With reference to the proportion of high discomfort (score ≥ 6) in the non-sedated group, young age (P < 0.001), female sex (P = 0.03), and no history of endoscopy (P < 0.001) were the factors related to increased discomfort; significant differences were also found for smoking status (P = 0.033) and endoscopists (P = 0.011) (Table 2). For the sedated group, young age (P < 0.001), female sex (P < 0.001), and no history of endoscopy (P = 0.004) were the factors associated with increased discomfort; significant differences were also found for smoking status (P < 0.001), type of sedation (P < 0.001), and endoscopist (P = 0.027). There was a marginal difference based on alcohol consumption (P = 0.055) (Table 3). Additionally, for the proportion of high discomfort in this group, young age (P < 0.001) and no history of endoscopy (P = 0.018) were the factors associated with increased discomfort. Significant differences were also found based on alcohol intake (P = 0.001). However, there was only a marginal difference based on the smoking status (P = 0.055) (Table 3).

| Discomfort score value median (quartile ranges) | Proportion of high discomfort (score ≥ 6) | |||

| Age | ||||

| ≤ 39 | 6 (4-8) | P < 0.001 | 60.5% (23/38) | P < 0.001 |

| 40-49 | 4 (4-6) | Kruskal-Wallis test | 45.1% (51/113) | χ2 test |

| 50-59 | 4 (2-6) | 34.7% (66/190) | ||

| 60-69 | 4 (2-4) | 18.3% (48/262) | ||

| ≥ 70 | 2 (0-4) | 9.9% (17/171) | ||

| Male sex | 4 (2-4) | P < 0.001 | 23.5% (130/554) | P = 0.003 |

| Female sex | 4 (2-6) | Mann-Whitney U test | 34.1% (75/220) | χ2 test |

| BMI | ||||

| ≥ 25 | 4 (2-6) | P = 0.796 | 27.2% (62/228) | P = 0.773 |

| < 25 | 4 (2-6) | Mann-Whitney U test | 26.2% (143/546) | χ2 test |

| Height | ||||

| < 150 cm | 4 (2-5) | P = 0.007 | 25.7% (9/35) | P = 0.219 |

| 150-160 cm | 4 (2-6) | Kruskal-Wallis test | 29.4% (53/180) | χ2 test |

| 160-170 cm | 4 (2-4) | 22.7% (75/330) | ||

| ≥ 170 cm | 4 (2-6) | 29.7% (68/229) | ||

| Non-smoker | 4 (2-6) | P = 0.003 | 26.5% (104/393) | P = 0.033 |

| Past smoker | 4 (2-4) | Kruskal-Wallis test | 22.4% (57/255) | χ2 test |

| Current smoker | 4 (2-6) | 34.9% (44/126) | ||

| Non-drinker | 4 (2-6) | P = 0.098 | 29.4% (91/309) | P = 0.291 |

| Normal drinker | 4 (2-4) | Kruskal-Wallis test | 24.9% (96/386) | χ2 test |

| Heavy drinker | 4 (2-4) | 22.8% (18/79) | ||

| History of endoscopy (+) | 4 (2-4) | P < 0.001 | 24.8% (180/727) | P < 0.001 |

| History of endoscopy (-) | 6 (4-7) | Mann-Whitney U test | 53.2% (25/47) | χ2 test |

| History of gastrectomy (+) | 2 (2-4) | P = 0.202 | 16.7% (3/18) | P = 0.428 |

| History of gastrectomy (-) | 4 (2-6) | Mann-Whitney U test | 26.7% (202/756) | Fisher's exact test |

| Butylscopolamine (+) | 2 (2-4) | P = 0.115 | 20.6% (14/68) | P = 0.249 |

| Butylscopolamine (-) | 4 (2-6) | (Mann-Whitney U test | 27.1% (191/706) | χ2 test |

| Biopsy performed (+) | 4 (2-6) | P = 0.461 | 39.1% (9/23) | P = 0.163 |

| Biopsy performed (-) | 4 (2-6) | Mann-Whitney U test | 26.1% (196/751) | χ2 test |

| Lugol’s solution (+) | 4 (2-6) | P = 0.950 | 40.0% (2/5) | P = 0.612 |

| Lugol’s solution (-) | 4 (2-6) | (Mann-Whitney U test | 26.4% (203/769) | Fisher's exact test |

| Endoscope | ||||

| Normal diameter | 4 (2-6) | P = 0.737 | 28.6% (6/21) | P = 0.826 |

| Small diameter | 4 (2-6) | Mann-Whitney U test | 26.4% (199/753) | χ2 test |

| Hiatal hernia (+) | 4 (2-6) | P = 0.257 | 27.6% (113/410) | P = 0.472 |

| Hiatal hernia (-) | 4 (2-6) | Mann-Whitney U test | 25.3% (92/364) | χ2 test |

| Sedation agent | ||||

| No use | 4 (2-6) | - | 26.5% (205/774) | - |

| Pethidine alone | - | - | ||

| Midazolam alone | - | - | ||

| Pethidine and Midazolam | - | - | ||

| Discomfort score value median (quartile ranges) | Proportion of high discomfort (score 6 or higher) | |||

| Age | ||||

| ≤ 39 | 4 (2.5-6) | P < 0.001 | 40.5% (17/42) | P < 0.001 |

| 40-49 | 2 (2-4) | Kruskal-Wallis test | 17.9% (35/195) | χ2 test |

| 50-59 | 2 (0-4) | 10.8% (26/241) | ||

| 60-69 | 2 (0-4) | 6.0% (21/348) | ||

| ≥ 70 | 2 (0-2) | 3.5% (4/115) | ||

| Male sex | 2 (0-4) | P < 0.001 | 10.9% (43/396) | P = 0.942 |

| Female sex | 2 (2-4) | Mann-Whitney U test | 11.0% (60/545) | χ2 test |

| BMI | ||||

| ≥ 25 | 2 (0-4) | P = 0.155 | 11.3% (31/275) | P = 0.837 |

| < 25 | 2 (0-4) | Mann-Whitney U test | 10.8% (72/666) | χ2 test |

| Height | ||||

| < 150 cm | 2 (1-4) | P = 0.185 | 13.9% (11/79) | P = 0.109 |

| 150-160 cm | 2 (0-4) | Kruskal-Wallis test | 9.6% (35/366) | χ2 test |

| 160-170 cm | 2 (0-4) | 9.2% (29/314) | ||

| ≥ 170 cm | 2 (0-4) | 15.4% (28/182) | ||

| Non-smoker | 2 (0-4) | P < 0.001 | 10.1% (60/595) | P = 0.055 |

| Past smoker | 2 (0-4) | Kruskal-Wallis test | 9.9% (23/232) | χ2 test |

| Current smoker | 2 (2-4) | 17.5% (20/114) | ||

| Non-drinker | 2 (0-4) | P = 0.055 | 9.5% (43/452) | P = 0.001 |

| Normal drinker | 2 (0-4) | Kruskal-Wallis test | 10.3% (44/426) | χ2 test |

| Heavy drinker | 2 (1-5) | 25.4% (16/63) | ||

| History of endoscopy (+) | 2 (0-4) | P = 0.004 | 10.3% (90/875) | P = 0.018 |

| History of endoscopy (-) | 2 (2-4) | Mann-Whitney U test | 19.7% (13/66) | χ2 test |

| History of gastrectomy (+) | 2 (0-2.5) | P = 0.477 | 16.7% (2/12) | P = 0.631 |

| History of gastrectomy (-) | 2 (0-4) | Mann-Whitney U test | 10.9% (101/929) | Fisher's exact test |

| Butylscopolamine (+) | 2 (0-4) | P = 0.187 | 10.6% (47/443) | P = 0.755 |

| Butylscopolamine (-) | 2 (0-4) | Mann-Whitney U test | 11.2% (56/498) | χ2 test |

| Biopsy performed (+) | 2 (0-3.5) | P = 0.287 | 11.5% (3/26) | P = 0.757 |

| Biopsy performed (-) | 2 (0-4) | Mann-Whitney U test | 10.9% (100/915) | Fisher's exact test |

| Lugol’s solution (+) | 1 (0.5-1.5) | P = 0.35 | 0.0% (0/2) | P = 1.00 |

| Lugol’s solution (-) | 2 (0-4) | Mann-Whitney U test | 11.0% (103/939) | Fisher's exact test |

| Endoscope | ||||

| Normal diameter | 2 (2-4) | P = 0.197 | 10.8% (4/37) | P = 1.00 |

| Small diameter | 2 (0-4) | Mann-Whitney U test | 11.0% (99/904) | Fisher's exact test |

| Hiatal hernia (+) | 2 (0-4) | P = 0.891 | 12.3% (45/365) | P = 0.279 |

| Hiatal hernia (-) | 2 (0-4) | Mann-Whitney U test | 10.1% (58/576) | χ2 test |

| Sedation agent | ||||

| No use | - | - | ||

| Pethidine alone | 2 (0-4) | P < 0.001 | 11.7% (93/797) | P = 0.186 |

| Midazolam alone | 2 (0-4) | Kruskal-Wallis test | 10.5% (2/19) | Fisher's exact test |

| Pethidine and Midazolam | 0 (0-2) | 6.4% (8/125) | ||

Based on multiple regression analysis (Table 4), young age (regression coefficient for -1 years: 0.08, P < 0.001), female sex (regression coefficient: 0.45, P = 0.013), shorter height (regression coefficient for -1 cm: 0.02, P = 0.024), current smoking status (regression coefficient: 0.35, P = 0.036), and presence of hiatal hernia (regression coefficient: 0.34, P = 0.003) were the factors that significantly increased the discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy. The use of sedation significantly reduced discomfort. Pethidine (regression coefficient: -1.47, P < 0.001), midazolam (regression coefficient: -1.63, P = 0.001), and their combination (regression coefficient: -2.92, P < 0.001) were found to significantly reduce the discomfort. The individual endoscopist performing the procedure was also associated with the discomfort (regression coefficient estimates: Maximum 2.78 differences). According to the multiple regression analysis performed in both groups, the regression coefficient of heavy alcohol consumption was 0.90 (P = 0.001) in the sedation group and 0.008 (P = 0.78) in the non-sedation group. Therefore, under sedation, the discomfort experienced by a heavy drinker was greater than that experienced by a non-heavy drinker.

| Regression coefficient | Upper limit of 95%CI | Lower limit of 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (+ 1) | -0.08 | -0.09 | -0.07 | < 0.001 |

| Sex (male) | -0.45 | -0.79 | -0.10 | 0.013 |

| BMI (+ 1) | -0.002 | -0.03 | 0.03 | 0.903 |

| Height (+ 1) | -0.02 | -0.04 | -0.003 | 0.024 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Past smoker | -0.06 | -0.32 | 0.20 | 0.638 |

| Current smoker | 0.35 | 0.02 | 0.67 | 0.036 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Normal drinker | -0.05 | -0.27 | 0.18 | 0.680 |

| Heavy drinker | 0.20 | -0.21 | 0.61 | 0.337 |

| Has no endoscopic experience | 0.22 | -0.20 | 0.65 | 0.300 |

| History of gastrectomy | 0.36 | -0.41 | 1.14 | 0.362 |

| Butylscopolamine use | -0.04 | -0.35 | 0.27 | 0.802 |

| Biopsy performed | 0.11 | -0.51 | 0.72 | 0.729 |

| Lugol’s solution use | 1.02 | -0.61 | 2.64 | 0.221 |

| Normal diameter endoscope | 0.48 | -0.09 | 1.05 | 0.101 |

| Hiatal hernia | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.57 | 0.003 |

| Sedation agent | ||||

| Pethidine alone | -1.47 | -1.71 | -1.22 | < 0.001 |

| Midazolam alone | -1.63 | -2.61 | -0.66 | 0.001 |

| Pethidine and midazolam | -2.92 | -3.36 | -2.49 | < 0.001 |

Based on the multiple regression analysis, the factors associated with increased discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy were young age, female sex, short height, current smoking status, and hiatal hernia. Individual endoscopists were also related to the discomfort. Additionally, heavy alcohol consumption diminished sedation. This is consistent with the previous report that revealed young[4-7] and female patients[4,5,8,9] have higher levels of discomfort. The high discomfort in younger patients is considered to be mainly due to gag reflex[10]. The high discomfort in women is considered due to a low pain threshold[11]. Additionally, it is reported that vomiting, belching, or retching increases significantly in patients with hiatal hernia[10], which can be the cause of the high levels of discomfort in such cases.

The results of the present study suggest that current smokers have increased discomfort due to esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Although smoking is considered a cause of gag reflex[12], smoking was not identified as a significant factor of discomfort in the previous studies[7,9,10]. Thus, current smoking status associated with increased discomfort has been newly identified in the present study, which may be due to the larger sample size of the present study. It is reported that smokers have chronic laryngitis[13]; hence, chronic irritation to the throat may be the cause of gag reflex in smokers. Additionally, since there was no difference in the discomfort experienced between past-smokers and non-smokers, smoking cessation could help eliminate the increasing discomfort. Although previous studies only investigated the discomfort or gag reflex based on body mass index as a body-type factor in[5,9,10]; short height may be related to high discomfort levels because the scope diameter is relatively large. Therefore, in this study, height was also included as a factor and was found to be significantly related to discomfort. Although this is a new finding of interest, univariate analysis for high discomfort was not significantly different, and the regression coefficient in multiple regression analysis is relatively small and, therefore, has less clinical relevance.

Sedation was useful as it significantly reduced discomfort, and the use of either pethidine, midazolam, or their combination was effective. However, heavy alcohol consumption reduced the effect of sedation. Sedation is reported to be less effective in heavy drinkers[14]. Previous studies have shown that the requisite doses of benzodiazepines and the combination of benzodiazepine and opioid are higher for heavy drinkers than for others[15,16]. Unlike previous reports, in the majority of the cases in the present study, pethidine was used and was found to be less effective in heavy drinkers. Therefore, we believe that discomfort can be predicted from age, sex, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, which can be easily obtained before examination.

The limitation of this study is the possibility of a selection bias since it is a retrospective cross-sectional study from a single facility. However, various information was analyzed in connection with the health check-up data in many participants. Additionally, anxiety and pharyngeal sensitivity, which were identified as factors of discomfort in the previous studies, could not be analyzed before the examination[4-7,9]. However, anxiety and pharyngeal sensitivity are rarely evaluated in general practice; therefore, it is meaningful to investigate the factor of discomfort by the information obtained ordinarily in daily practice. The strengths of the present study are that it is a large-size study, and smoking status was identified for the first time as a contributing factor to discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

In conclusion, young and female patients experience more discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Furthermore, the discomfort in current smokers may increase. Additionally, heavy alcohol consumption reduces the effect of sedatives. These factors are useful because they can be easily obtained, and we can take remedial measures for reducing discomfort.

Discomfort due to esophagogastroduodenoscopy contributes to a negative experience and reduces the patients’ satisfaction. Therefore, it is important to reduce discomfort as much as possible. By identifying the factors that cause discomfort, we can take remedial measures such as using sedation.

However, not all factors of discomfort have been elucidated yet. Most previous studies have conducted investigations only in several hundred subjects, which is a relatively small sample.

The aim of this study was to elucidate the contributing factors of discomfort in transoral esophagogastroduodenoscopy by a large-scale cross-sectional study.

This study was a retrospective observational study using a questionnaire for the improvement of hospital services. Discomfort was evaluated using a face scale between 0 and 10 with a 6-level questionnaire. Univariate and multiple regression analyses were performed to investigate the factors related to the discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy. The primary outcome was the result of a multiple regression. In this analysis, the objective variable was the discomfort score and the explanatory variables were age, sex, height, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol intake, hiatal hernia, history of gastrectomy, biopsy during examination, Lugol’s solution usage, administration of butylscopolamine with/without a sedative (pethidine, midazolam, or both), endoscope model, history of endoscopy, and endoscopists.

Finally, 1715 patients were enrolled in this study. Based on multiple regression analysis, young age, female sex, shorter height, current smoking status, and presence of hiatal hernia [regression coefficients of 0.08, P < 0.001 (for -1 years); 0.45, P = 0.013; 0.02, P = 0.024 (for -1 cm); 0.35, P = 0.036; and 0.34, P = 0.003, respectively] were factors that significantly increased the discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Alternatively, sedation significantly reduced discomfort; pethidine (regression coefficient: -1.47, P < 0.001) and midazolam (regression coefficient: -1.63, P = 0.001) both individually and in combination (regression coefficient: -2.92, P < 0.001) significantly reduced the discomfort. A difference in the endoscopist performing the procedure was also associated with discomfort. Additionally, for the proportion of a high discomfort level (score ≥ 6) in the sedated group, significant differences were also found based on alcohol intake in univariate analyses (P = 0.001).

The present study clearly identified the factors associated with discomfort in esophagogastroduodenoscopy using a large-size cross-sectional study. Young age, female sex, and current smoking were identified as the contributive factors. Smoking status was a newly identified predictor of this study. Furthermore, heavy alcohol consumption was noted to diminish the effect of the sedative(s). These factors are useful because they can be easily obtained, and we can take remedial measures for reducing discomfort.

Prospective research is needed to clarify whether predicting discomfort and taking measures to alleviate it can effectively increase patient satisfaction.

We thank the medical staff of Kameda Medical Center for supporting us.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Figueiredo EG, M'Koma A S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Lee HY, Lim SM, Han MA, Jun JK, Choi KS, Hahm MI, Park EC. Assessment of participant satisfaction with upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in South Korea. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4124-4129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ko HH, Zhang H, Telford JJ, Enns R. Factors influencing patient satisfaction when undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:883-891, quiz 891.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cohen LB, Ladas SD, Vargo JJ, Paspatis GA, Bjorkman DJ, Van der Linden P, Axon AT, Axon AE, Bamias G, Despott E, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Fassoulaki A, Hofmann N, Karagiannis JA, Karamanolis D, Maurer W, O'Connor A, Paraskeva K, Schreiber F, Triantafyllou K, Viazis N, Vlachogiannakos J. Sedation in digestive endoscopy: the Athens international position statements. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:425-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Froehlich F, Schwizer W, Thorens J, Köhler M, Gonvers JJ, Fried M. Conscious sedation for gastroscopy: patient tolerance and cardiorespiratory parameters. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:697-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Campo R, Brullet E, Montserrat A, Calvet X, Moix J, Rué M, Roqué M, Donoso L, Bordas JM. Identification of factors that influence tolerance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:201-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mulcahy HE, Kelly P, Banks MR, Connor P, Patchet SE, Farthing MJ, Fairclough PD, Kumar PJ. Factors associated with tolerance to, and discomfort with, unsedated diagnostic gastroscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1352-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abraham N, Barkun A, Larocque M, Fallone C, Mayrand S, Baffis V, Cohen A, Daly D, Daoud H, Joseph L. Predicting which patients can undergo upper endoscopy comfortably without conscious sedation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:180-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ono S, Niimi K, Fujishiro M, Nakao T, Suzuki K, Ohike Y, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Yamazaki T, Koike K. Ultrathin endoscope flexibility can predict discomfort associated with unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:346-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Miyake K, Kusunoki M, Ueki N, Yamada A, Nagoya H, Kodaka Y, Shindo T, Kawagoe T, Gudis K, Futagami S, Tsukui T, Sakamoto C. Classification of patients who experience a higher distress level to transoral esophagogastroduodenoscopy than to transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:397-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Enomoto S, Watanabe M, Yoshida T, Mukoubayashi C, Moribata K, Muraki Y, Shingaki N, Deguchi H, Ueda K, Inoue I, Maekita T, Iguchi M, Tamai H, Kato J, Fujishiro M, Oka M, Mohara O, Ichinose M. Relationship between vomiting reflex during esophagogastroduodenoscopy and dyspepsia symptoms. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:325-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ono S, Niimi K, Fujishiro M, Takahashi Y, Sakaguchi Y, Nakayama C, Minatsuki C, Matsuda R, Hirayama-Asada I, Tsuji Y, Mochizuki S, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Ozeki A, Matsumoto L, Ohike Y, Yamazaki T, Koike K. Evaluation of preferable insertion routes for esophagogastroduodenoscopy using ultrathin endoscopes. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5045-5050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dickinson CM, Fiske J. A review of gagging problems in dentistry: I. Aetiology and classification. Dent Update. 2005;32:26-28, 31-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ban MJ, Kim WS, Park KN, Kim JW, Lee SW, Han K, Chang JW, Byeon HK, Koh YW, Park JH. Korean survey data reveals an association of chronic laryngitis with tinnitus in men. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Standards of Practice Committee of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Lichtenstein DR, Jagannath S, Baron TH, Anderson MA, Banerjee S, Dominitz JA, Fanelli RD, Gan SI, Harrison ME, Ikenberry SO, Shen B, Stewart L, Khan K, Vargo JJ. Sedation and anesthesia in GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:815-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cook PJ, Flanagan R, James IM. Diazepam tolerance: effect of age, regular sedation, and alcohol. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;289:351-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ominami M, Nagami Y, Shiba M, Tominaga K, Maruyama H, Okamoto J, Kato K, Minamino H, Fukunaga S, Sugimori S, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, Watanabe T, Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Prediction of Poor Response to Modified Neuroleptanalgesia with Midazolam for Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Digestion. 2016;94:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |