Copyright

©The Author(s) 2017.

World J Gastrointest Endosc. Feb 16, 2017; 9(2): 55-60

Published online Feb 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i2.55

Published online Feb 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i2.55

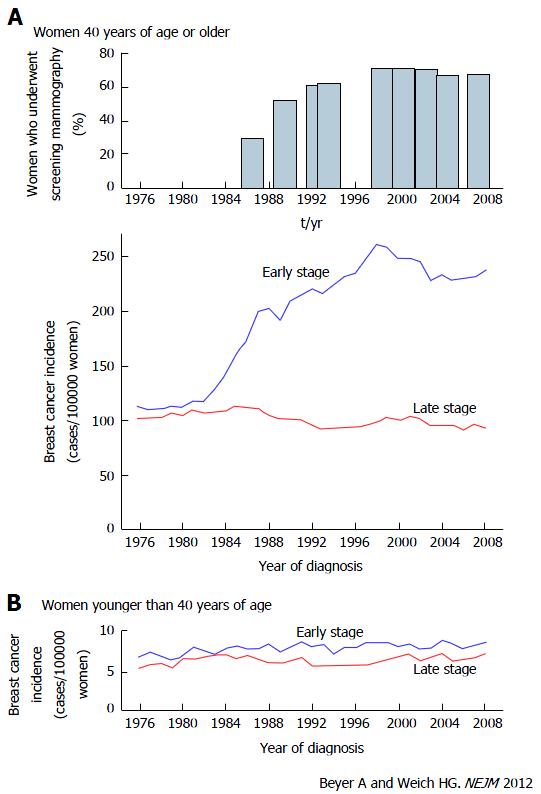

Figure 1 Trends of breast cancer incidence before and after mammographic screenings in the United States.

A: Use of mammographic screening and incidence of stage-specific breast cancer among women 40 years of age and older; B: Incidence of stage-specific breast cancer among women younger than 40 years of age[12].

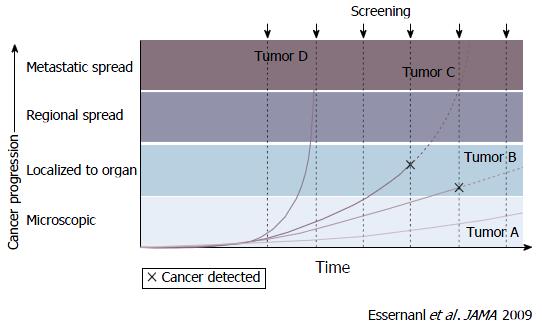

Figure 2 Screen detection capability based on tumor biology and growth rates[13].

The growth rates of cancer vary and are divided into 4 categories: Rapid, slow, very slow, and non-progressive. Periodic screening detects slow-growing (Tumor B) and non-progressive (Tumor A) cancers early, and finds some progressive cancer (Tumor C) early. Tumor A remains undetectable and causes no morbidity during the patients’ lifetime without screening. However, rapid-growing cancer (Tumor D) which is a fatal tumor is not screened earlier and can cause death even with treatment.

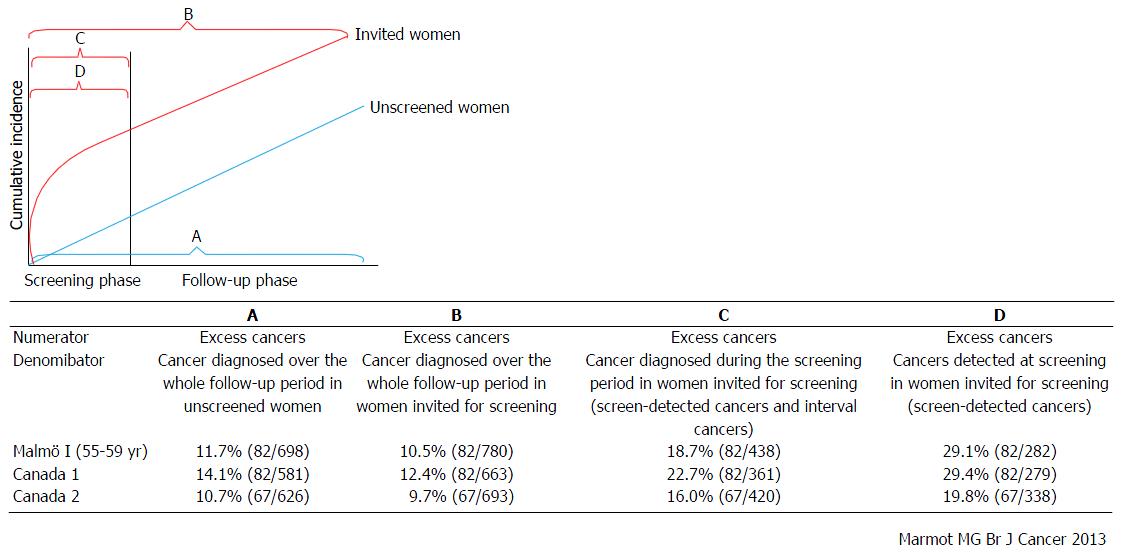

Figure 3 Estimation of frequency of overdiagnosis on the basis of the results of Malmö and Canadian studies.

The frequency of overdiagnosis was calculated on the basis of 2 randomized controlled trials for mammographic screening using 4 methods with different denominators as follows: A: Excess cancers as the frequency of cancers diagnosed over the whole follow-up period in unscreened women; B: Excess cancers as the frequency of cancers diagnosed over the whole follow-up period in women invited for screening; C: Excess cancers as the frequency of cancers diagnosed during the screening period in women invited for screening; D: Excess cancers as the frequency of cancers detected at screening in women invited for screening[16].

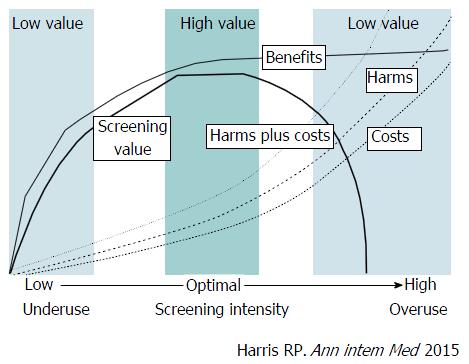

Figure 4 A value framework for cancer screening.

The value of cancer screening strategies is linked to the screening intensity (population screened, frequency, and sensitivity of the test used) and is determined by the balance among benefits (e.g., cancer mortality reduction), harms (e.g., anxiety from false-positive test results, harms of diagnostic procedures, labeling, and overdiagnosis leading to overtreatment), and costs. The value of cancer screening is determined by a trade-off between benefits vs harms and costs. As the intensity increases, the benefits of screening rapidly increase. However, as the intensity increases beyond an optimal level, the increase in benefits slows down whereas harms and costs increase rapidly, and the value decreases[14].

- Citation: Hamashima C. Overdiagnosis of gastric cancer by endoscopic screening. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(2): 55-60

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i2/55.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i2.55