Published online Sep 28, 2015. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i21.2344

Peer-review started: April 22, 2015

First decision: July 25, 2015

Revised: August 19, 2015

Accepted: September 7, 2015

Article in press: September 8, 2015

Published online: September 28, 2015

Processing time: 155 Days and 13.3 Hours

Rituximab is currently used not only in the treatment of B-cell lymphoma but also for various other diseases, including autoimmune diseases, post-transplant graft vs host disease, and rejection following kidney transplants. Due to rituximab’s widespread use, great progress has been made regarding research into complications that arise from its use, one of the most serious being the reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV), and efforts continue to establish guidelines for preventive treatment against this occurrence. This report discusses preventive measures against rituximab-induced HBV reactivation and future objectives.

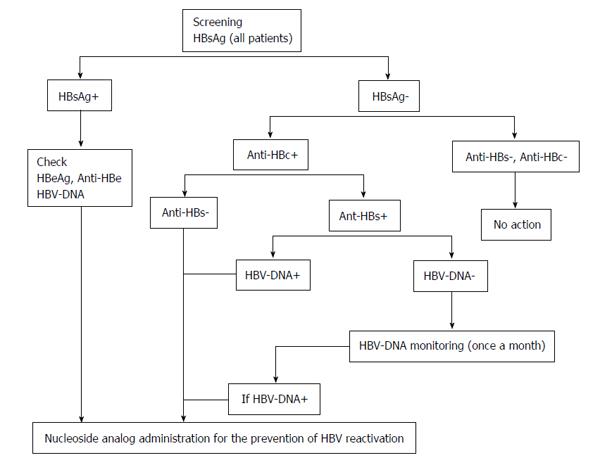

Core tip: For preventive measures against hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation during rituximab treatment, hepatitis B surface (HBs) antigen positive and HBc antibody positive/HBs antibody negative patients are subject to prophylactic treatment with nucleoside analogs. During rituximab treatment, the HBV-DNA levels of patients who are HBc antibody positive (HBs antibody positive or negative) are ideally monitored with PCR once a month. If the PCR results are positive, the administration of nucleoside analogs is initiated. However, since monitoring HBV-DNA levels is expensive, it might be preferable to follow the HBs antibodies instead. Due to wide differences in the insurance situations in each country, including the follow-up intervals, further research must determine ideal follow-up intervals. However, no standard exists for the timing of this treatment’s termination. For HBs antigen negative patients who also receive nucleoside analog treatment, it will be necessary in the future to evaluate the possibility of switching to a vaccine when a patient becomes HBs antibody positive.

- Citation: Tsutsumi Y, Yamamoto Y, Ito S, Ohigashi H, Shiratori S, Naruse H, Teshima T. Hepatitis B virus reactivation with a rituximab-containing regimen. World J Hepatol 2015; 7(21): 2344-2351

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v7/i21/2344.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i21.2344

Rituximab, which improves the prognosis of CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma, is generally indispensable for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma[1-3]. Rituximab inhibits the production of various antibodies by targeting CD20 positive B-cells and is effective for a range of conditions, including diopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, chronic rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis with applications to other diseases as well[4-7]. On the other hand, extensive studies have also recently been conducted on rituximab’s side effects, which include reports not only of typical infusion reactions but also various infectious diseases due to its immune suppressive effects: Cytomegalovirus, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, parvovirus infection, and Herpes zoster[8-11]. Although hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation has been previously reported to be a complication of chemotherapy[12-16], this phenomenon has drawn greater attention due to reports that argue that the frequency of reactivation is higher in patients treated with rituximab than those who only received chemotherapy[17-24]. The best way to deal with HBV reactivation is to prevent it[25,26]. In this review, we describe the prevention and treatment of HBV reactivation based on previous reports and discuss a summary and future objectives.

After HBV infection, HBV-DNA synthesis is initially suppressed by cytokine production from NK and other cells. A subsequent cytotoxic T-cell (CTL) reaction occurs due to the presence of CD8-positive T lymphocytes. Because hepatitis is triggered by CTLs, a time lag likely exists between the HBV infection and the manifestation of hepatitis[27,28]. On the other hand, rituximab induces CD4 lymphopenia[29,30]. In a mouse model, B-cell depletion reduced the number and the fraction of CD4 memory T-cells and impaired immunity against virus infection[31]. A reduction in CD20 Bcells shifted the CD4 effector phenotype to that of enhanced interferon-γ, interleukin (IL)-2, and tumor necrosis factor. Perhaps the depletion of CD20 positive B-cells reduces the production of IL-7 and IL-15, both of which are critical for memory T-cell survival, from monocytes or stromal cells[31]. Furthermore, HBV replication is likely accelerated by the indirect effects of B-cell depletion on immune globulin production. It has been reported that rituximab treatment induces a change in CD8 distribution[30]. This might reduce the number of CD8-positive cells and the subsequent acceleration of HBV replication. Once the number of CD8-positive T-cells recovers, cells are produced that specifically target HBV. However, since memory T-cells are impaired by their reduced numbers, CD8-positive T-cells randomly attack HBV, resulting in severe hepatitis[31].

Rituximab not only affects B-cells but T-cells as well and accelerates HBV replication. This is a primary factor in the induction of HBV reactivation by the administration of rituximab alone.

When combined with chemotherapy, the HBV reactivation rate during rituximab treatment has been reported to be 20%-55% overall and 3% in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) negative patients[32-36]. HBV reactivation can be caused by chemotherapy alone. However, rituximab more easily induces HBV reactivation independently upon combined treatment with chemotherapy or steroid treatment[18,26]. The frequency of HBV reactivation is also higher with combination treatments including rituximab compared to chemotherapy alone or a combination chemotherapy and steroid treatment[18,37]. Risk factors for HBV reactivation in patients receiving chemotherapy include being male, lack of HBs antibody, HBs antigen positivity, presence of a precore mutant, HBV-DNA level, anthracycline/steroid use, transplantation, second/third line treatment, youth, and the presence of lymphoma[35,37-39]. However, when rituximab is used, the risk factors for HBV reactivation are narrowed to a lack of HBs antibody, youth, and being male[37]. All the above reports are retrospective analyses of patients who were HBs antigen positive and who therefore were subject to prophylactic nucleoside analog therapy. In the future, patient groups must be identified who tend to experience reactivation even when receiving such therapy.

Many remaining problems must be addressed. One is whether the attending physician performs antibody or DNA tests before initiating chemotherapy or a rituximab/chemotherapy combination. This issue is rather basic; yet a surprising report by Méndez-Navarro et al[40] in 2011 showed that serological screening of HBV is only done in less than 40% of cases before treatment. In some cases, HBV reactivation went undetected because no HBV screening was conducted. Zurawska et al[41] analyzed the effect of HBsAg screening by dividing patients into three groups: screening, non-screening, and only screening of high-risk patients. Their results showed that the group that was screened before treatment had the highest prevention rate of HBV reactivation (10-fold); screening the high-risk patient group was the most cost effective measure. When comparing the screening and non-screening groups, the former was more cost effective. Screening prevents HBV reactivation.

Another problem is the screening method. Some patients were diagnosed as HBc antibody negative when using the EIA method (AxSYM Assay: Abbot Laboratories, Chiba, Japan, 2005), but they were diagnosed as HBc antibody positive with the CLIA method (Architect Assay: Abbott Laboratories, Chiba, Japan, 2013). Thus, in the past, we overlooked an HBV reactivation risk factor since our treatment was based on AxSYM results. Therefore, reports on HBV reactivation cannot be compared since the results were biased by the screening method. This affects the evaluation of risk factors and prophylactic administration. International standardization of screening methods is needed.

The risk factors for HBV reactivation include being male, lack of HBs antibody, HBs antigen positive, presence of precore mutant, HBV-DNA level, anthracycline/steroid combination therapy, transplantation, second/third line treatments, youth, and the presence of lymphoma; When rituximab is used, the risk factors are narrowed down to a lack of HBs antibody, youth, and being male; Currently, the screening rate for HBV is only 30%-40%; Standardization of screening methods is a future task.

HBV-DNA mutations must be considered when assessing the potential difficulties in the treatment of HBV using nucleoside analogs. Pelizzari et al[42] reported that the mutation rate in HBV-DNA with lamivudine is lower than the rate during treatment for hepatitis B. However, in their study, the observation period was short and they analyzed too few cases. Several mutations were reported in HBV reactivated patients. Main of these mutations were developed in immune-active HBsAg regions, such as M103I-L109I-T118K-P120A-Y134H-S143L-D144E-S171F. In other patients, C48G-V96A-L175S-G185E-V190A mutations were observed whose function escaped the T-cell-mediated responses for HBV. An N-linked glycosylation site was observed in a major hydrophilic loop in HBV reactivated patients without HBsAg[43]. Compared to treatment with standard chemotherapy with or without rituximab, the mutation rate during the prophylactic treatment of HBV-DNA with lamivudine was approximately 15%-20%. Therefore, this indicates no significant difference in the HBV-DNA mutation rate with lamivudine between the prophylactic and standard HBV hepatitis treatment periods[44,45]. A fatal case was also described in which HBV reactivation was caused by HBV-DNA mutation during R-CHOP treatment, although not at an early stage[46]. Recently, encouraging results have been reported on the effectiveness of entecavir in the prevention of HBV reactivation[47]. Due to the low frequency of the emergence of a resistant HBV strain with entecavir use, this is the first choice for the prophylactic treatment of patients with high viral load or patients who require a long prophylactic treatment period[47].

Lamivudine resistance was induced early when a nucleoside analog such as fludarabine was used with rituximab[48]. Similar reports have been noted for the induction of HBV-DNA mutations by nucleoside analogs when steroids or fludarabine were used with rituximab[49]. Note that the combined use of such purine analogs as fludarabine and cladribine with rituximab tends to induce HBV-DNA mutations. A report on HBV reactivation with bendamustine (an alkylating agent) as well as a nucleoside analog has also been published. However, HBV-DNA mutations with these agents were not evaluated and their effectiveness in this regard remains unknown[50].

With regard to HBV-DNA mutations, entecavir is desirable for prophylactic treatment in the event of HBV reactivation due to its poor ability to induce mutations in HBV-DNA. However, its cost is problematic, and measures must be enacted that are suitable for different countries.

The presence of HBV mutations corresponds to the frequency of the emergence of resistant strains with standard nucleoside analogs.

Perhaps HBV mutations will increase with a combination treatment of steroids or anti-cancer drugs such as purine analogs that have a strong immune suppressive effect.

There is an international consensus that nucleoside analog administration is necessary in HBs antigen positive patients since prophylactic treatment is effective for the prevention of HBV reactivation and reduces mortality in this group[51-53]. Guidelines for each analog are shown in Table 1. When referring to the guideline treatments for HBs antigen positive chronic hepatitis, entecavir use is desirable when the HBV-DNA concentration exceeds 20000 IU/mL, while lamivudine use is adequate if the HBV-DNA concentration falls under 20000 IU/mL. In addition, in HBV-DNA-positive cases, the possible existence of YMDD mutations must be determined beforehand. If such mutations are detected, using tenofovir or the combined use of two nucleoside analogs might become necessary. As mentioned previously, entecavir is more desirable for the prevention of HBV reactivation due to its low induction of resistant strains during treatment. Ideally, it is desirable to start prophylactic treatment two weeks after the administration of nucleoside analogs since the drugs are most effective during this period. However, there is no standard protocol regarding the starting time for treatment since the specific condition of each individual patient often plays a role. In our clinic, steroids are not used on patients who are HBs antigen positive. A fatality was previously observed in a group of patients who were receiving steroid/rituximab combination therapy that caused HBV-DNA mutation and HBV reactivation even though the patient was HBs antigen negative. We believe that the use of steroids should be avoided, at least in HBs antigen positive patients[47].

| AASLD | Subject to preventive treatment if HBsAg positive or anti-HBc positive and HBV-DNA positive. If HBV-DNA concentration is less than 20000 IU or for a shortened treatment (< 1 yr), lamivudine or telbivudine is desirable. If HBV-DNA concentration exceeds 20000 IU and long-term treatment is necessary, entecavir or tenofovir is desirable. lf HBV-DNA concentration remains less than 2000 IU six months after the completion of treatment, the treatment should be discontinued; otherwise treatment shall continue (2009) |

| APASL | There are no guidelines (2005) |

| EASL | HBsAg cases are subject to treatment, and HBV-DNA is measured in these cases, although there is no defined value in which treatment recommendations can be made. Lamivudine is most commonly used; however, it is best used in cases with low HBV-DNA concentration or when resistant strains are less likely to emerge. In high HBV-DNA concentration cases or when there is a high risk of resistance, entecavir is desirable. Careful follow-up of HBV-DNA concentration and liver function is necessary for HBsAg negative, Anti-HBc positive, and HBV-DNA negative cases. Vaccination is recommended in HBV seronegative cases (2009) |

| JAPAN | Subject to nucleoside analog treatment if HBsAg positive or if HBsAg negative, and anti-HBs or HBc positive plus HBV-DNA positive. If HBV-DNA is negative, HBV-DNA is monitored monthly and nucleoside analogs are administered when HBV-DNA becomes positive. Entecavir is recommended as the nucleoside analog. The timing of the termination of the nucleoside analog treatment shall be determined in accordance with the treatment for type B chronic hepatitis if HBsAg is positive. If the patient is anti-HBs or anti-HBc positive, a nucleoside analog is administered for 12 mo after the completion of immunosuppressive therapy or chemotherapy. During this time, nucleoside analog treatment will be discontinued if HBV-DNA is negative and ALT is normal. Patients are closely observed for 12 mo after treatment with nucleoside analogs (2009) |

For HBs antigen positive patients, treatment with nucleoside analogs is necessary to prevent HBV reactivation.

Although from the point of view of preventing drug resistant HBV emergence, using entecavir as the initial treatment is advantageous, due to its excessive cost, substitution with lamivudine is acceptable.

Treatment based on the guidelines might be helpful.

The HBc antibody positive/HBs antigen negative serotype is further divided into naïve (HBs antibody positive) and occult types (HBs antibody negative). However, since HBV reactivation is often observed in HBc antibody positive/HBs antigen negative cases, it may be preferable to divide HBc antibody positive/HBs antigen negative cases based on whether they are positive or negative for HBs antibodies. For HBc antibody positive patients, perhaps HBV reactivation is induced by rituximab. Although Hui et al[36] reported a 3%-25% reactivation rate, prophylactic treatment may be desirable since the mortality is relatively high (30%-38%) after reactivation occurs[36,54-56]. In 2013, Huang et al[47] conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of the prophylactic administration of entecavir on the frequency of HBV reactivation in HBc antibody positive patients. In their report, unlike in retrospective analyses, the prophylactic administration of entecavir was the most important factor, at least for HBc antibody positive patients[47]. Furthermore, Seto et al[57] recently reported frequent reactivation of HBV in patients with 10 mIU/mL HBs antibody prior to rituximab treatment. In HBc antibody positive patients, prophylactic treatment is necessary, at least for those who are antibody negative prior to rituximab treatment (occult type). We believe that the prophylactic administration of a nucleic acid analog is preferable in HBc antibody positive/HBs antigen negative/HBs antibody negative cases.

HBc antibody positivity can cause HBV reactivation. Attention is required since mortality is high after reactivation occurs.

Patients who are both HBc antibody positive and HBs antibody negative are subjected to prophylactic treatment with nucleoside analogs.

There are reports of HBV reactivation in HBc-ab negative/HBs-ag positive/HBs-ab positive cases[21,32,36], and reactivation occurred in 6.9% of them[43]. HBV reactivation in HBc antibody negative/HBs antigen negative/HBs antibody positive cases has also been reported (albeit in small numbers)[21,36], and reactivation was reported in 3.4% of them[43].

We previously reported decreased HBs and HBc antibodies as well as induced reactivation after combination rituximab/chemotherapy in HBs antibody positive patients[17,24,25,58-60]. HBs antibody in particular decreased in patients with < 300 mIU/mL and disappeared in patients with < 100 mIU/mL after combination therapy with rituximab and chemotherapy[58-60]. For patients who were originally HBc antibody positive/HBs antibody positive but became HBs antibody negative after continuous treatment with rituximab, perhaps HBV reactivation can be induced by maintenance therapy with rituximab. Therefore, the possibility of HBV reactivation must be evaluated for group receiving maintenance therapy with rituximab. Since a case has been documented in which HBV reactivation occurred even though the patient had an HBs antibody titer of 868 mIU/mL, monthly follow-ups must be conducted during treatment for HBV-DNA positive patients[20]. However, such prophylactic treatment is expensive and HBV reactivation remains a possibility. At present, HBV-DNA follow-up is deemed adequate if the follow-up of HBs and HBc antibodies is extended to once a month. We must identify those who require prophylactic treatment from among HBc antibody positive/HBs antigen negative/HBs antibody positive and HBc antibody negative/HBs antigen negative/HBs antibody positive patients.

Particular attention must be paid to patients with < 300 mIU/mL of HBs antibody during maintenance treatment with rituximab since the HBs antibody status might become negative (follow-up of HBs antibody concentration is required).

Since HBV reactivation was reported even in patients with a high HBs antibody titer, HBs antibody follow-up is not sufficient for detecting the occurrence of reactivation. Monthly follow-up for the presence of HBV-DNA is necessary during treatment.

As for the prophylactic administration to prevent HBV reactivation, low HBV drug resistance is desirable. Although different guidelines exist, 0.5 mg of entecavir might be desirable with regard to both effectiveness and minimizing drug resistance. Depending on the cost of the drug and individual financial circumstances, 100 mg of lamivudine is also acceptable, although drug resistant strains are induced more easily. In this case, various guidelines are helpful in the selection of appropriate prophylactic drugs[51-53]. If HBV reactivation occurs, the patient should be dealt with based on the treatment of acute hepatitis B. Although the first choice for treatment is 0.5 or 100 mg of lamivudine, interferon is usually employed as well for acute hepatitis since nucleoside analogs do not take effect immediately upon HBV reactivation. However, in the case of HBV reactivation, interferon is difficult to apply since reactivation occurs after rituximab or chemotherapy treatment and prolonged bone marrow suppression might occur. Interferon’s administration is also undesirable because it can exacerbate liver damage[61]. In our clinic, liver protective drugs (glycyrrhizic and ursodeoxycholic acids) are used together, although they might remain insufficient. If resistance develops to entecavir or lamivudine, 10 mg of adefovir or 200 mg of tenofovir should be used[52,53,61,62]. However, great caution is required since switching treatment drugs may induce further HBV drug resistance[63]. Tenofovir has been reported to be effective for lamivudine as well as adefovir resistant HBV strains[64-66].

We must evaluate whether to discontinue nucleoside analog administration in patients receiving those drugs that promote HBV reactivation. Since HBs antibody might become negative during rituximab treatment, discontinuation should be considered after the treatment’s completion. An additional problem exists with regard to determining the duration of the discontinuation period. Cases of HBV reactivation even after long periods of discontinuation have been documented. For example, even after HBs antibody became temporarily positive, it disappeared later and HBV reactivation was induced[60,67]. If nucleoside analog treatment is given to HBs antibody negative patients who later become antibody positive, such treatment can be discontinued[53]. On the other hand, HBV vaccination is unable to suppress HBV reactivation[68]. If rituximab is administered continuously, HBs antibody may not be induced even after HBV vaccination. It is necessary to evaluate not only the induction of HBs antibody after HBV vaccination but also diseases that are appropriate for the discontinuation of nucleoside analog treatment. Based on the above discussion, Figure 1 shows the modified guidelines from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Although entecavir is the first choice for prophylactic treatment against HBV reactivation, the decision to use it might also be based on financial conditions, and the guidelines should be referred to when selecting the appropriate drug.

When lamivudine resistance emerges, the treatment drug should be switched to adefovir or tenofovir.

Since nucleoside analogs do not take effect immediately upon HBV reactivation, combination treatment with interferon should be considered. However, bone marrow suppression must be considered for patients with hematological disorders.

The discontinuation of nucleoside analogs must be considered in the future. For HBs antigen negative patients, the discontinuation of nucleoside analog treatment may be possible through a vaccine.

Regarding the prevention of HBV reactivation, based on results from clinical studies conducted so far, not only HBs antigen positive patients but also those who are HBs antibody negative/HBc antibody positive might be eligible for prophylactic treatment. By employing combination rituximab/chemotherapy, safer treatment for malignant lymphomas is possible. On the other hand, HBV reactivation during maintenance therapy with rituximab must be considered. The discontinuation of nucleoside analog treatment may be possible through combined administration of an HBV vaccine in patients who are receiving nucleoside analogs as a preventive treatment against HBV reactivation (primarily for antibody negative cases).

P- Reviewer: Frider B, Yoo BC S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Maloney DG, Liles TM, Czerwinski DK, Waldichuk C, Rosenberg J, Grillo-Lopez A, Levy R. Phase I clinical trial using escalating single-dose infusion of chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (IDEC-C2B8) in patients with recurrent B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1994;84:2457-2466. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Maloney DG, Grillo-López AJ, White CA, Bodkin D, Schilder RJ, Neidhart JA, Janakiraman N, Foon KA, Liles TM, Dallaire BK. IDEC-C2B8 (Rituximab) anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in patients with relapsed low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood. 1997;90:2188-2195. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Maloney DG, Grillo-López AJ, Bodkin DJ, White CA, Liles TM, Royston I, Varns C, Rosenberg J, Levy R. IDEC-C2B8: results of a phase I multiple-dose trial in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:3266-3274. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Khellaf M, Charles-Nelson A, Fain O, Terriou L, Viallard JF, Cheze S, Graveleau J, Slama B, Audia S, Ebbo M. Safety and efficacy of rituximab in adult immune thrombocytopenia: results from a prospective registry including 248 patients. Blood. 2014;124:3228-3236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close DR, Stevens RM, Shaw T. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2572-2581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1803] [Cited by in RCA: 1861] [Article Influence: 88.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Castillo-Trivino T, Braithwaite D, Bacchetti P, Waubant E. Rituximab in relapsing and progressive forms of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Petrarca A, Rigacci L, Caini P, Colagrande S, Romagnoli P, Vizzutti F, Arena U, Giannini C, Monti M, Montalto P. Safety and efficacy of rituximab in patients with hepatitis C virus-related mixed cryoglobulinemia and severe liver disease. Blood. 2010;116:335-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bermúdez A, Marco F, Conde E, Mazo E, Recio M, Zubizarreta A. Fatal visceral varicella-zoster infection following rituximab and chemotherapy treatment in a patient with follicular lymphoma. Haematologica. 2000;85:894-895. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Sharma VR, Fleming DR, Slone SP. Pure red cell aplasia due to parvovirus B19 in a patient treated with rituximab. Blood. 2000;96:1184-1186. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Suzan F, Ammor M, Ribrag V. Fatal reactivation of cytomegalovirus infection after use of rituximab for a post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Goldberg SL, Pecora AL, Alter RS, Kroll MS, Rowley SD, Waintraub SE, Imrit K, Preti RA. Unusual viral infections (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and cytomegalovirus disease) after high-dose chemotherapy with autologous blood stem cell rescue and peritransplantation rituximab. Blood. 2002;99:1486-1488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Galbraith RM, Eddleston AL, Williams R, Zuckerman AJ. Fulminant hepatic failure in leukaemia and choriocarcinoma related to withdrawal of cytotoxic drug therapy. Lancet. 1975;2:528-530. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Hoofnagle JH, Dusheiko GM, Schafer DF, Jones EA, Micetich KC, Young RC, Costa J. Reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection by cancer chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:447-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Thung SN, Gerber MA, Klion F, Gilbert H. Massive hepatic necrosis after chemotherapy withdrawal in a hepatitis B virus carrier. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1313-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lau JY, Lai CL, Lin HJ, Lok AS, Liang RH, Wu PC, Chan TK, Todd D. Fatal reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection following withdrawal of chemotherapy in lymphoma patients. Q J Med. 1989;73:911-917. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Liang RH, Lok AS, Lai CL, Chan TK, Todd D, Chiu EK. Hepatitis B infection in patients with lymphomas. Hematol Oncol. 1990;8:261-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tsutsumi Y, Kanamori H, Mori A, Tanaka J, Asaka M, Imamura M, Masauzi N. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus with rituximab. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4:599-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tsutsumi Y, Shigematsu A, Hashino S, Tanaka J, Chiba K, Masauzi N, Kobayashi H, Kurosawa M, Iwasaki H, Morioka M. Analysis of reactivation of hepatitis B virus in the treatment of B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Hokkaido. Ann Hematol. 2009;88:375-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Skrabs C, Müller C, Agis H, Mannhalter C, Jäger U. Treatment of HBV-carrying lymphoma patients with Rituximab and CHOP: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Leukemia. 2002;16:1884-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Westhoff TH, Jochimsen F, Schmittel A, Stoffler-Meilicke M, Schafer JH, Zidek W, Gerlich WH, Thiel E. Fatal hepatitis B virus reactivation by an escape mutant following rituximab therapy. Blood. 2003;102:1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dervite I, Hober D, Morel P. Acute hepatitis B in a patient with antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen who was receiving rituximab. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:68-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ng HJ, Lim LC. Fulminant hepatitis B virus reactivation with concomitant listeriosis after fludarabine and rituximab therapy: case report. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:549-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jäeger G, Neumeister P, Brezinschek R, Höfler G, Quehenberger F, Linkesch W, Sill H. Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) as consolidation of first-line CHOP chemotherapy in patients with follicular lymphoma: a phase II study. Eur J Haematol. 2002;69:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yang SH, Kuo SH. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus during rituximab treatment of a patient with follicular lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:325-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tsutsumi Y, Tanaka J, Kawamura T, Miura T, Kanamori H, Obara S, Asaka M, Imamura M, Masauzi N. Possible efficacy of lamivudine treatment to prevent hepatitis B virus reactivation due to rituximab therapy in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:58-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tsutsumi Y, Kawamura T, Saitoh S, Yamada M, Obara S, Miura T, Kanamori H, Tanaka J, Asaka M, Imamura M. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in a case of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and rituximab: necessity of prophylaxis for hepatitis B virus reactivation in rituximab therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:627-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Guidotti LG, Rochford R, Chung J, Shapiro M, Purcell R, Chisari FV. Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science. 1999;284:825-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 949] [Cited by in RCA: 913] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Webster GJ, Reignat S, Maini MK, Whalley SA, Ogg GS, King A, Brown D, Amlot PL, Williams R, Vergani D. Incubation phase of acute hepatitis B in man: dynamic of cellular immune mechanisms. Hepatology. 2000;32:1117-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Besada E, Koldingsnes W, Nossent JC. Long-term efficacy and safety of pre-emptive maintenance therapy with rituximab in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: results from a single centre. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52:2041-2047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mélet J, Mulleman D, Goupille P, Ribourtout B, Watier H, Thibault G. Rituximab-induced T cell depletion in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: association with clinical response. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2783-2790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Misumi I, Whitmire JK. B cell depletion curtails CD4+ T cell memory and reduces protection against disseminating virus infection. J Immunol. 2014;192:1597-1608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lok AS, Liang RH, Chiu EK, Wong KL, Chan TK, Todd D. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in patients receiving cytotoxic therapy. Report of a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:182-188. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Nakamura Y, Motokura T, Fujita A, Yamashita T, Ogata E. Severe hepatitis related to chemotherapy in hepatitis B virus carriers with hematologic malignancies. Survey in Japan, 1987-1991. Cancer. 1996;78:2210-2215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kumagai K, Takagi T, Nakamura S, Sawada U, Kura Y, Kodama F, Shimano S, Kudoh I, Nakamura H, Sawada K. Hepatitis B virus carriers in the treatment of malignant lymphoma: an epidemiological study in Japan. Ann Oncol. 1997;8 Suppl 1:107-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, Ho WM, Steinberg JL, Tam JS, Hui P, Leung NW, Zee B, Johnson PJ. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol. 2000;62:299-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hui CK, Cheung WW, Zhang HY, Au WY, Yueng YH, Leung AY, Leung N, Luk JM, Lie AK, Kwong YL. Kinetics and risk of de novo hepatitis B infection in HBsAg-negative patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:59-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NW, Lam WY, Mo FK, Chu MT, Chan HL, Hui EP, Lei KI, Mok TS. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:605-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Yeo W, Zee B, Zhong S, Chan PK, Wong WL, Ho WM, Lam KC, Johnson PJ. Comprehensive analysis of risk factors associating with Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1306-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kim HY, Kim W. Chemotherapy-related reactivation of hepatitis B infection: updates in 2013. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14581-14588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Méndez-Navarro J, Corey KE, Zheng H, Barlow LL, Jang JY, Lin W, Zhao H, Shao RX, McAfee SL, Chung RT. Hepatitis B screening, prophylaxis and re-activation in the era of rituximab-based chemotherapy. Liver Int. 2011;31:330-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zurawska U, Hicks LK, Woo G, Bell CM, Krahn M, Chan KK, Feld JJ. Hepatitis B virus screening before chemotherapy for lymphoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3167-3173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Pelizzari AM, Motta M, Cariani E, Turconi P, Borlenghi E, Rossi G. Frequency of hepatitis B virus mutant in asymptomatic hepatitis B virus carriers receiving prophylactic lamivudine during chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies. Hematol J. 2004;5:325-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Salpini R, Colagrossi L, Bellocchi MC, Surdo M, Becker C, Alteri C, Aragri M, Ricciardi A, Armenia D, Pollicita M. Hepatitis B surface antigen genetic elements critical for immune escape correlate with hepatitis B virus reactivation upon immunosuppression. Hepatology. 2015;61:823-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 44. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update of recommendations. Hepatology. 2004;39:857-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2001;34:1225-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 642] [Cited by in RCA: 639] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Win LL, Powis J, Shah H, Feld JJ, Wong DK. Death from Liver Failure despite Lamivudine Prophylaxis during R-CHOP Chemotherapy due to Rapid Emergence M204 Mutations. Case Reports Hepatol. 2013;2013:454897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Huang YH, Hsiao LT, Hong YC, Chiou TJ, Yu YB, Gau JP, Liu CY, Yang MH, Tzeng CH, Lee PC. Randomized controlled trial of entecavir prophylaxis for rituximab-associated hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with lymphoma and resolved hepatitis B. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2765-2772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Picardi M, Pane F, Quintarelli C, De Renzo A, Del Giudice A, De Divitiis B, Persico M, Ciancia R, Salvatore F, Rotoli B. Hepatitis B virus reactivation after fludarabine-based regimens for indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: high prevalence of acquired viral genomic mutations. Haematologica. 2003;88:1296-1303. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Miyagawa M, Minami M, Fujii K, Sendo R, Mori K, Shimizu D, Nakajima T, Yasui K, Itoh Y, Taniwaki M. Molecular characterization of a variant virus that caused de novo hepatitis B without elevation of hepatitis B surface antigen after chemotherapy with rituximab. J Med Virol. 2008;80:2069-2078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Tsutsumi Y, Ogasawara R, Miyashita N, Tanaka J, Asaka M, Imamura M. HBV reactivation in malignant lymphoma patients treated with rituximab and bendamustine. Int J Hematol. 2012;95:588-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1794] [Cited by in RCA: 1778] [Article Influence: 98.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Liaw YF, Leung N, Guan R, Lau GK, Merican I, McCaughan G, Gane E, Kao JH, Omata M. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2005 update. Liver Int. 2005;25:472-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1152] [Cited by in RCA: 1154] [Article Influence: 72.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Coppola N, Tonziello G, Pisaturo M, Messina V, Guastafierro S, Fiore M, Iodice V, Sagnelli C, Stanzione M, Capoluongo N. Reactivation of overt and occult hepatitis B infection in various immunosuppressive settings. J Med Virol. 2011;83:1909-1916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Ji D, Cao J, Hong X, Li J, Wang J, Chen F, Wang C, Zou S. Low incidence of hepatitis B virus reactivation during chemotherapy among diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients who are HBsAg-negative/ HBcAb-positive: a multicenter retrospective study. Eur J Haematol. 2010;85:243-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Sagnelli E, Pisaturo M, Martini S, Filippini P, Sagnelli C, Coppola N. Clinical impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection in immuno–suppressed patients. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:384-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Seto WK, Chan TS, Hwang YY, Wong DK, Fung J, Liu KS, Gill H, Lam YF, Lie AK, Lai CL. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients with previous hepatitis B virus exposure undergoing rituximab-containing chemotherapy for lymphoma: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3736-3743. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Tsutsumi Y, Ogasawara R, Kamihara Y, Ito S, Yamamoto Y, Tanaka J, Asaka M, Imamura M. Rituximab administration and reactivation of HBV. Hepat Res Treat. 2010;2010:182067. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Tsutsumi Y, Yamamoto Y, Tanaka J, Asaka M, Imamura M, Masauzi N. Prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation under rituximab therapy. Immunotherapy. 2009;1:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Tsutsumi Y, Yamamoto Y, Shimono J, Ohhigashi H, Teshima T. Hepatitis B virus reactivation with rituximab-containing regimen. World J Hepatol. 2013;5:612-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Abaalkhail F, Elsiesy H, AlOmair A, Alghamdi MY, Alalwan A, AlMasri N, Al-Hamoudi W. SASLT practice guidelines for the management of hepatitis B virus. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Chang TT, Gish RG, Hadziyannis SJ, Cianciara J, Rizzetto M, Schiff ER, Pastore G, Bacon BR, Poynard T, Joshi S. A dose-ranging study of the efficacy and tolerability of entecavir in Lamivudine-refractory chronic hepatitis B patients. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1198-1209. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Fung SK, Andreone P, Han SH, Rajender Reddy K, Regev A, Keeffe EB, Hussain M, Cursaro C, Richtmyer P, Marrero JA. Adefovir-resistant hepatitis B can be associated with viral rebound and hepatic decompensation. J Hepatol. 2005;43:937-943. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Peters MG, Hann Hw Hw, Martin P, Heathcote EJ, Buggisch P, Rubin R, Bourliere M, Kowdley K, Trepo C, Gray Df Df. Adefovir dipivoxil alone or in combination with lamivudine in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:91-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 466] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Pérez-Roldán F, González-Carro P, Villafáñez-García MC. Adefovir dipivoxil for chemotherapy-induced activation of hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:310-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Tillmann HL, Wedemeyer H, Manns MP. Treatment of hepatitis B in special patient groups: hemodialysis, heart and renal transplant, fulminant hepatitis, hepatitis B virus reactivation. J Hepatol. 2003;39 Suppl 1:S206-S211. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Dai MS, Chao TY, Kao WY, Shyu RY, Liu TM. Delayed hepatitis B virus reactivation after cessation of preemptive lamivudine in lymphoma patients treated with rituximab plus CHOP. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:769-774. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Awerkiew S, Däumer M, Reiser M, Wend UC, Pfister H, Kaiser R, Willems WR, Gerlich WH. Reactivation of an occult hepatitis B virus escape mutant in an anti-HBs positive, anti-HBc negative lymphoma patient. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:83-86. [PubMed] |