INTRODUCTION

The pancreaticobiliary junction is a complex structure composed of the biliary and pancreatic ducts, and is surrounded by the sphincter of Oddi. Although the sphincter of Oddi precludes the reflux of pancreatic juice into the bile duct, pancreaticobiliary reflux (PBR) may occur in case where the functioning of the sphincter of Oddi is impaired[1,2].

An anatomically abnormal pancreaticobiliary junction is termed as a “pancreaticobiliary maljunction” (PBM), and is characterized by the joining of the pancreatic and bile ducts outside the duodenal wall[3,4]. This deformity was first reported in 1916 in case with a choledochal cyst[5]. PBM is an important pathological condition as many studies have indicated that it may be associated with biliary malignancies[6].

Futhermore, several studies have been assessed the reflux of pancreatic juice into the bile duct in the absence of morphological PBM, and the relationship of such cases with biliary diseases, including biliary malignancies, is gaining prominence[2,7-12].

In this editorial, the current knowledge and diagnostic advancements concerning PBR are described.

ETIOLOGY

Anatomy and physiology

The ampulla of Vater is composed of the confluence of the biliary and pancreatic ducts, and the duodenum, and marks the transition from the embryologic foregut to the midgut. The ampulla includes the junction of the common bile duct and the pancreatic duct, the surrounding sphincter of Oddi, the fenestra choledochae, and the duodenal papilla. Although the arrangement of these intersections has some variability, the reported structural relation are common and predictable[13].

The sphincter of Oddi, the regulator of biliary and pancreatic drainage that enable intermittent biliary drainage, originates separately from the duodenal musculature and the periductal mesenchyme, and subseqently becomes incorporated into the duodenal wall. Anatomical studies suggest that the papilla and the duodenal wall contained components specific to the common channel, as well as components specific to the pancreatic and common bile duct that extend outside the duodenal wall.

The common channel is present in 55%-90% of cases[14-16]. The common channel ranges in length from 1 to 12 mm, with an a mean length of approximately 4 mm[14,17,18]. In addition to controlling secretion into the duodenum, the sphincter of Oddi also preclude the mixing of bile and pancreatic juice within the duct system. The long common channels with PBM may cause to become the sphincter mechanism impair and induce the reflux of pancreatic juice, as the pressure of the pancreatic duct is higher than that of the bile duct[2].

However, PBR in patients without PBM is being increasingly recognized[2,7-12], and may develop due to a number of reasons: dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi, periamupullary diverticula, endoscopic sphincterotomy, and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation. Of these, most cases of PBR without PBM seem to be caused by dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi[2].

Etiology of cancer

Although the etiology of biliary cancer in patients with PBR is not yet fully understood, PBR is believed to play an important role in bile duct carcinoma. Once PBR occurs in the pancreaticobiliary junction, the pancreatic and bile juices become mixed and regurgitated mutually, and stagnate in the gallbladder and the bile duct. As a result, activated pancreatic enzymes induce chronic inflammation of the biliary tree and lead to proliferation of the biliary epithelium; moreover this can even cause the expression of carcinogenic substances in the biliary system[19-22]. Therefore, the carcinogenesis process in cases of biliary cancer with PBR is believed to involve the hyperplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence. Several factors that are reportedly related to carcinogenesis in case of biliary cancer have been identified including p53 mutations, microsatellite instability, Bcl-2, and k-Ras point mutations[6,23-28].

CLASSIFICATION

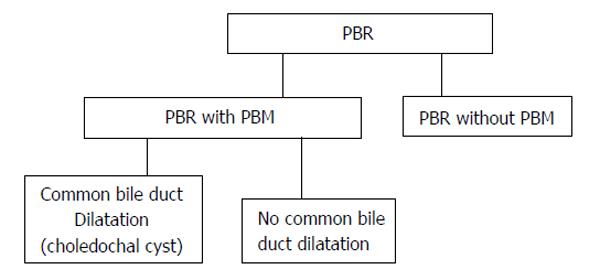

PBR can be divided into two categories on the presence or absence of PBM. PBM can also be divided into two categories on the presence or absence of common bile duct dilatation (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Classification of pancreaticobiliary reflux.

PBR: Pancreaticobiliary reflux; PBM: Panceraticobiliary maljunction.

PBM with choledochal cysts

Choledochal cysts are rare congenital biliary tract anomalies formed by biliary tree dilatation. Although the relative frequency of this abnormality in the Western population is 1 in 100000-150000 live births, it is markedly high frequency in Asian countries, particularly Japan, where it may be observed in up to 1 in 1000[29]. The main clinical symptoms include abdominal pain, vomiting, jaundice, and fever. Although the incidence of cholangitis is unclear, cholangitis was observed as a preoperative symptom in 13.2% of patients[6]. Choledochal cysts are commonly divided into several categories on the anatomical features. In 1959, Alonso-lej et al[30] devised a classification for choledochal cysts that was modified in 1977 by Todani et al[31]. According to Todani’s system, choledochal cysts can be divided into five main types. Neverthless, in this system, almost all patients with choledochal cysts fall into three categories (Todani’s type Ia, Ic and IV-A), and are related with PBM.

PBR may contribute to dilatation of the biliary tree[32,33]. Babbit[34] suggested an etiological mechanism for choledochal cyst shaping; it was proposed that enzymes activated in refluxed pancreatic juice induce inflammation, and finaly lead to damage and cystic dilatation of the biliary wall. This theory, however, does not explain the development of all choledochal cysts, as showed by choledochal cysts of newbone infant, which are known to be congenital rather than degenerative.

Biliary tract malignancies are noted in 21.6% of patients with choledochal cysts who are aged > 15 years, whereas biliary malignancies are much rarer in children who present aged < 15 years (0.1%)[6]. Immediate and exact diagnosis of a choledochal cyst, followed by surgical treatment, is crucial consequently.

PBM without choledochal cysts

PBM without a choledochal cyst may result in the reflux of pancreatic juice into the bile duct and may present clinical symptoms similar to those observed in case with PBM with a choledochal cyst. Cholangitis was observed as a preoperative symptom in 8.9% of patients[6]. However, only few patients with PBM without a choledochal cyst have symptoms in childhood; thus, in these patients, PBM tends to be diagnosed at a later stage than in those with a choledochal cyst[6,35]. Pancreatic juice is often refluxed into the biliary duct in PBM patients, and this may be associated with a high frequency of biliary cancer among such patients. While both PBM patients with and those without choledochal cysts are at a risk for biliary malignancies, they differ in the site of malignancy in the biliary tract[6].

In a previous study, biliary cancer was noted in 21.6% of adult patients with choledochal cysts, and in 42.2% of patients with PBM without biliary dilatation. Of all cases of biliary cancer associated with PBM without biliary dilatation, 88.1% were cancers of the gallbladder[6].

PBR without PBM

Lately, several researches on the reflux of pancreatic juice into the bile duct in case without PBM have been published, and the relationship of such a condition with biliary diseases, especially biliary malignancies, is attracting considerable attention[1,2,7-12,36-38]. However, these cases do not present specific clinical symptoms and also could not be acculately detected by using current available imaging modalities based on the morphological changes. Thus, it was difficult to predict and detect PBR without PBM. Generally, PBR in these patients is diagnosed on the basis of elevated pancreatic enzyme levels in bile juice samples, or by using magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) after secretin injection.

Anderson et al[9] demonstrated that elevated amylase levels in bile juice taken from indwelling T-tubes, suggestive of PBR were found in 81% (21 of 26) of patients with biliary disease without PBM. Horaguchi et al[8] presented that elevated amylase levels in bile juice after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) were found in 26% (46 of 178) of patients with a normal junction. Similarly, Sakamoto et al[38] detected elevated amylase levels in bile juice juice in 20% (39 of 196) of patients undergoing cholecystectomy without PBM[33]. Kamisawa et al[2] focused on the hypothesis that a relatively long common channel without PBM may be related to PBR. They defined a high confluence of the pancreaticobiliary ducts as a common channel length of more than 6 mm, in which communication may be sustained even when the sphincter of Oddi is contracted. They reported that a high confluence of the pancreaticobiliary ducts was found in 1.9% (65 of 3459) of patients who underwent ERCP in their single institute, and that the incidences of gallbladder cancer in patients with a high confluence of the pancreaticobiliary ducts was very high compared to that in controls.

Recently, a multi-center trial in Japan revealed that elevated amylase levels in bile juice after ERCP were found in 5.5% (23 of 420) of patients with a normal junction[36]. This trial showed that the presence of a relative long common channel (not shorter than 5 mm) was the only significant factor for PBR in multivariate analysis, and that the incidence of high amylase levels was significantly higher in patients with gallbladder cancer than in those without gallblader cancer.

DIAGNOSIS

PBM

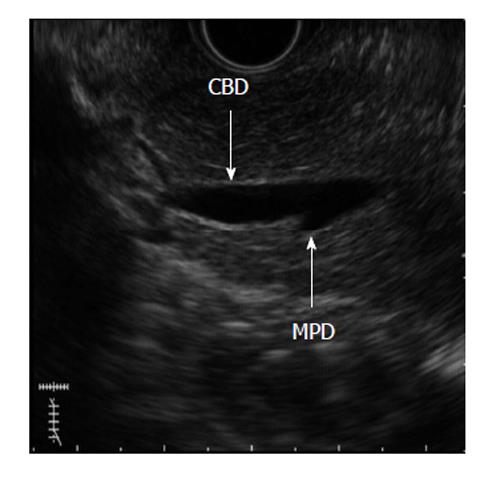

PBM can be detected with ERCP, ultrasonography (US), endoscopic US (EUS), computed tomography and MRCP. ERCP is the gold standard method for diagnosis of PBM, and pancreatography through the minor duodenal papilla can directly demonstrate pancreatobiliary reflux in PBM patients. When the contrast medium is injected endoscopically through the minor duodenal papilla, it is possible to monitor the reflux of contrast medium into the bile duct through the common channel without outflow into the duodenum[2]. Although ERCP is the diagnostic standard method for PBM, it is somewhat invasive and has a non-negligible risk of morbidity. US can detect choledochal cysts as well as abnormalities of the gallbladder that are possibly associated with PBM. However, because US cannot directly detect PBM, it may be suitable for use only as a screening tool. Moreover, EUS has a high spatial resolution and therefore is another modality capable of detecting PBM (Figure 2). However, it is operator dependent and offers a less objective evaluation. In addition, MRCP is a completely non-invasive procedure and causes no adverse reactions due to the contrast medium; however, it may offer a slightly lower spatial resolution than ERCP.

Figure 2 A 56-year-old female with pancreaticobiliary maljunction without choledochal cyst.

Endoscopic ultrasound image shows pancreaticobiliary maljunction. CBD: Common bile duct; MPD: Main pancreatic duct.

PBR without PBM

Several researchers have described that elevated amylase levels in bile juice samples after ERCP or during the operation (which suggest reflux of pancreatic juice and contrast medium into the pancreatic duct during intraoperative cholangiography) are seen in patients without PBM[1,2,7-12,36]. The normal values of pancreatic enzymes in bile have yet to be fully elucidated. Many researchers use the normal values of pancreatic enzymes in plasma as a reference for detecting PBR without PBM. Some researchers have applyed radioimmunoassays of biliary trypsin in bile samples collected from a T-tube inserted into the common bile duct after surgery[9,39]. Among these methods, the most commonly used method involves the assessmente of bile sample taken directly from the gallbladder at the time of cholecystectomy or ERCP.

However, several researchers have reported that PBR without PBM can be diagnosed by using secretin-stimulating magnetic resonance imaging[10,37]. This method makes it possible to demonstrate pancreatic juice movement on changes in pancreatic or bile duct diameter in consequence of secretin injection. However, this does not visualize pancreatic juice movement directly, and a few controversial reports have therefore questioned the validity of pancreatic juice movement demonstrated by using this method[37,39-41]. Therefore, a robust method is still required.

Advanced diagnosis for detecting PBR without PBM

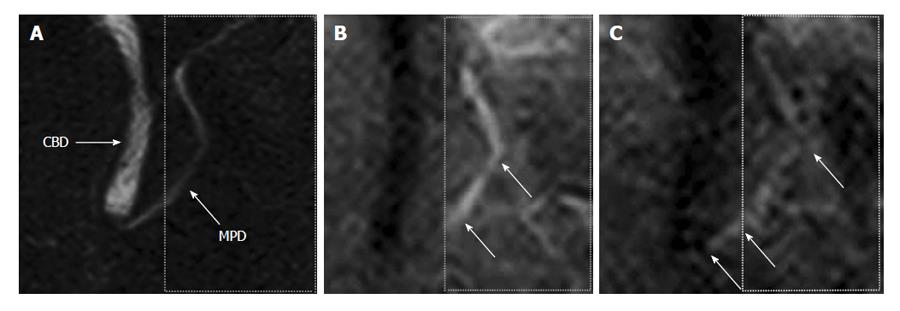

Recently, a new magnetic resonance-based method (time-SLIP) has been developed for direct visualization of pancreatic juice flow (Figure 3). Initially, this technique allowed the examination of blood flow in vessels to a region of interest[42,43]. This technique could enable the visualization of the flow of bile and pancreatic juices and may allow the evaluation of various pancreatico-biliary diseases based on this information[44,45]. This method revealed new knowledge regarding physiology of bile and pancreatic juices, and was applied for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.

Figure 3 A 47-year-old male with normal volunteer.

A: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image. Labelling pulse of pancreas juice is applying to box surrounded by dotted lines on pancreas juice in body and caudal portion of the 3) main pancreatic duct; B: Time-SLIP image is not showing movement of pancreatic juice; C: Flow of pancreatic juice from body of the pancreas into head of pancreas is noted by high signal intensity (arrows). Reprinted from Sugita et al[43] (by permission of Wiley Periodicals, Inc). CBD: Common bile duct; MPD: Main pancreatic duct.

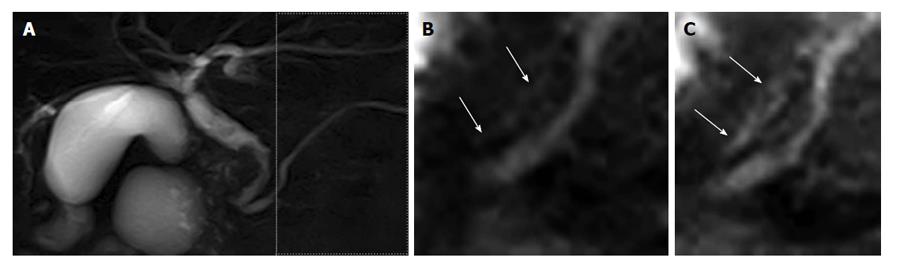

Moreover, this new technique enables the visualization of the reflux of pancreatic juice flow into the bile duct without PBM, although no clinical results have yet been reported (Figure 4). This technique, involving the use of the pancreatic juice as an intrinsic imaging agent, facilitates the examination of pancreatic juice movement similar to more physiolosical situation. In addition, this technique is not time consuming. Accordingly, the method can be easily adopted as a screening tool for PBR. Therefore, this new technique may reveal what proportion of patients without PBM have PBR, and whether reflux is related to biliary carcinogenesis. Further clinical studies are required.

Figure 4 A 75-year-old male with common bile duct carcinoma without pancreaticobiliary maljunction.

A: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows the irregular wall throughout the entire common bile duct, with bile duct carcinoma revealed by biopsy. During endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, amylase level was measured in the bile. The amylase level in the collected bile was 1415 IU/L, higher than the upper limit of serum amylase of 130 IU/L; B and C: Labeled pancreatic juice in the main pancreatic duct refluxing into the common bile duct. Reprinted from Sugita et al[43] (by permission of Wiley Periodicals, Inc).

THERAPY

Once PBM is diagnosed, preventive flow-diversion surgery (biloenteric anastomosis and bile duct resection) is excuted for patients with choledochal cysts[4,6]. These operations are often associated with complications such as anastomotic stricture, cholangitis, and secondary liver cirrhosis; therefore, careful follow-up is needed[46].

Nevertheless, any treatment for patients with PBM without biliary dilatation and biliary malignancy is controversial. Preventive cholecystectomy is first choise in many institutions because the majority of biliary malignancies that develop in PBM patients without biliary dilatation are cancers of the gallbladder[4,6,47,48]. On the other hand, excision of the extrahepatic bile duct along with the gallbladder is selected by some surgeons[4,24,49,50]. The treatment for patients with PBR without PBM is not defined because the pathology of PBR without PBM is less well understood. Moreover, strategies for the screening and prevention of PBR without PBM are not yet established.

CONCLUSION

PBR is an important pathologic state that can cause biliary malignancy. PBR can occur regardless of the presence of PBM. Although it has been possible to diagnose PBM by using various imaging modalities, PBR without PBM has remained difficult to assess. Thus, the pathological features of PBR without PBM have not yet been fully elucidated. Recently, a new method for diagnosing PBR without PBM has been introduced, and this would enable a better understanding the feature of PBR without PBM.