Published online Jun 27, 2014. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i6.384

Revised: March 16, 2014

Accepted: May 31, 2014

Published online: June 27, 2014

Processing time: 218 Days and 17.7 Hours

Occult hepatitis B infection (OBI), is characterized by low level hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA in circulating blood and/or liver tissue. In clinical practice the presence of antibody to hepatitis B core antigen in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-/anti-HBs-negative subjects is considered indicative of OBI. OBI is mostly observed in the window period of acute HBV infection in blood donors and in recipients of blood and blood products, in hepatitis C virus chronic carriers, in patients under pharmacological immunosuppression, and in those with immunodepression due to HIV infection or cancer. Reactivation of OBI mostly occurs in anti-HIV-positive subjects, in patients treated with immunosuppressive therapy in onco-hematological settings, in patients who undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, in those treated with anti-CD20 or anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody, or anti-tumor necrosis factors antibody for rheumatological diseases, or chemotherapy for solid tumors. Under these conditions the mortality rate for hepatic failure or progression of the underlying disease due to discontinuation of specific treatment can reach 20%. For patients with OBI, prophylaxis with nucleot(s)ide analogues should be based on the HBV serological markers, the underlying diseases and the type of immunosuppressive treatment. Lamivudine prophylaxis is indicated in hemopoietic stem cell transplantation and in onco-hematological diseases when high dose corticosteroids and rituximab are used; monitoring may be indicated when rituximab-sparing schedules are used, but early treatment should be applied as soon as HBsAg becomes detectable. This review article presents an up-to-date evaluation of the current knowledge on OBI.

Core tip: In occult Hepatitis B infection (OBI), hepatitis B virus reactivation is more common in anti-HIV-positive subjects, in those in onco-hematological settings, in patients who undergo hemopoietic stem cell transplantation and in those treated with anti-CD20 or anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody. Reactivation may be severe and in nearly 20% of cases it may take a life-threatening course. The use of nucleot(s)ide analogues to prevent this reactivation is mandatory in hepatitis B surface antigen-negative/anti-hepatitis B core-positive patients in all conditions of strong and/or prolonged immunosuppression. We describe the characteristics of OBI in onco-hematological and rheumatological diseases, in solid cancers and in HIV infection.

- Citation: Sagnelli E, Pisaturo M, Martini S, Filippini P, Sagnelli C, Coppola N. Clinical impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection in immunosuppressed patients. World J Hepatol 2014; 6(6): 384-393

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v6/i6/384.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v6.i6.384

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major health problem in most countries, with approximately 2 billion people worldwide with serological evidence of previous exposure to the virus, of whom nearly 300 million have HBV chronic infection and over 1 million deaths per year are due to HBV-related cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1-6].

HBV infection is identified in most cases by the presence of circulating hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), but an HBsAg-negative HBV infection has also been described [Occult B infection (OBI)][7], characterized by low levels of HBV DNA in circulating blood[8,9] and/or in liver tissue[10]. OBI has also been described as a serological condition characterized by the presence of hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) in the absence of HBsAg and anti-HBs (isolated anti-HBc)[7,11-15]. OBI may be observed in the window period of acute HBV infection[16] in blood donors and in recipients of blood and blood products[9,17,18], in patients with HCV chronic infection[7,19], in cryptogenic chronic hepatitis, in patients under pharmacological suppression of the immune system[20,21] and in those with immunodepression due to HIV infection; it has also been associated to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma[22-30].

It has been shown that the hepatitis B virus maintains its pro-oncogenic properties in OBI[31] and that its presence in patients with chronic hepatitis C is associated with a higher risk of disease progression and HCC development[32-36] and with a reduced response to alfa interferon treatment[37-39]. The clinical importance of OBI is also underscored by the need for nucleot(s)ide treatment to prevent the recurrence of HBV infection in HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients in various immunosuppressive settings[40-42].

This review article presents an up-to-date evaluation of the current knowledge on OBI, focusing in particular on the clinical approach in onco-hematological and rheumatological diseases, solid cancers and HIV infection.

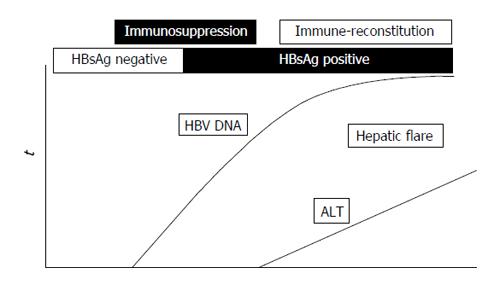

Reactivation of HBV infection in patients under immunosuppressive treatment is a well-known, life-threatening event described in HBsAg-positive patients (overt HBV infection) and in subjects with OBI[20,21,42-50]. The reactivation of HBV infection, overt or occult, is characterized by a marked enhancement of viral replication during immunosuppressive therapy, with a wide spread of HBV to uninfected hepatocytes and a substantial increase in the HBV DNA serum level followed by the restoration of the immune function after treatment withdrawal and consequent cytotoxic-T-cell-mediated necrosis of HBV-infected hepatocytes usually responsible for a hepatic flare and in some instances for liver failure and even death[42]. A schematic representation of the dynamics of serum HBV DNA and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) before and during the reactivation of OBI is shown in Figure 1.

Both in overt and occult infection the risk of HBV reactivation is estimated as high when immunosuppression is marked, particularly in onco-hematological patients (21%-67%), in those receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and in those treated with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab or with the monoclonal anti-CD52 antibody alemtuzumab, both responsible for profound, long-lasting immunosuppression[20,21,43,51-59]. Under these conditions HBV reactivation has a mortality rate close to 20%, due to a hepatic failure or to the progression of the underlying disease due to the discontinuation of specific treatment[51,60,61]. Besides host factors, also some virological characteristics have been described as possibly associated with HBV reactivation. In 7 of 84 HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients treated for hematological diseases or solid cancer, HBV reactivation was due to non-A HBV genotypes, core promoter and/or precore HBV mutants. In these 7 patients mutations known to impair HBsAg antigenicity were also detected[62]. A precore stop mutation (A1896) was detected in one patient with genotype Bj who developed fulminant liver failure[63]. Also sub-genotype D1 has been described as possibly associated with HBV reactivation in two studies, one from Egypt and one from Italy[21,64].

There is general agreement for the use of nucleos(t)ide analogues to prevent HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive immunosuppressed patients, whereas it is still a matter of debate whether subjects with occult HBV infection should be treated or closely monitored for early treatment once HBsAg positivity has developed.

A crucial role in the reactivation of OBI is played by the severity and duration of immunosuppression, which in turn reflects the extent of immunodepression due to the hematological disease and of the degree of immunosuppression induced by chemotherapy. The drugs commonly responsible for HBV reactivation are those used in hematological malignancy, such as fludarabine, anthracyclines, high dose corticosteroids[51,52] and, more recently, rituximab (anti-CD20) and alemtuzumab (anti-CD52)[53].

Evidence has become available in hematological malignancy that the reactivation of occult HBV infection is frequent in patients treated with rituximab or fludarabine in the absence of lamivudine prophylaxis[21,60,61]. However, due to the retrospective nature of most studies published, the geographical differences in HBV epidemiology and the genetic differences in HBV and the host have not been investigated, and the prevalence of HBV reactivation varies widely (from 3% to 45%)[21,48,52,65-69]. The first prospective study[65] on 244 occult HBV carriers with malignant lymphoma showed a reactivation in 8 (3.3%) cases, with a higher risk of reactivation in patients receiving rituximab plus corticosteroids than in those under a rituximab-sparing schedule. In a prospective study on patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), Yeo et al[20] reported reactivation of HBV infection in 5 of 21 (23.8%) patients treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) and in none of the 25 patients receiving only CHOP. Recently Fukushima et al[48] observed reactivation in 2 (4.1%) of 48 HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients. In addition, in 150 patients with lymphoma and a resolved HBV infection who received rituximab-based chemotherapy, Hsu et al[70] described an incidence of HBV reactivation and of HBV hepatic flares of 10.4 and 6.4, respectively, per person per year. Matsui et al[71] followed up for a median period of 20.5 mo 59 patients with isolated anti-HBc and lymphoma treated with rituximab-based chemotherapy and observed HBV reactivation in 4 (6.8%).

Lower prevalences of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative patients after rituximab-based therapy have been reported in two studies from eastern Asia, 1.5% and 4.2%, respectively[46,72]. In another Asian study only one (2.3%) of 43 DLBCL patients treated with an R-CHOP regimen showed reactivation of HBV replication[73], for which a remission was obtained with antiviral therapy with no need to discontinue chemotherapy. Koo et al[74] described HBV reactivation in two (3%) of 62 HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients treated with rituximab-based chemotherapy who did not undergo anti-HBV prophylaxis. More recently, the Asia Lymphoma Study Group investigated for HBV reactivation HBsAg-positive patients and HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients who received rituximab-based chemotherapy; the study was retrospective and performed on 340 patients, with a reactivation rate of 2.4% in subjects with OBI and 27.8% in HBsAg-positive patients[75].

The different frequency of cases with reactivation of occult HBV infection in different countries may explain, at least in part, the discordance in different national guidelines on lamivudine prophylaxis, some of which indicate the use of this nucleoside analogue for a pharmacological prophylaxis of HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients undergoing highly immunosuppressive treatment for onco-hematological diseases[76], and others conclude that the information available does not allow any routine prophylaxis to be recommended for these patients[77].

The data of a recent meta-analysis, however, suggest that rituximab-based chemotherapy increases the risk of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma[78], an observation of clinical importance to be taken into consideration for future guidelines.

Biological therapies targeting tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) have been used increasingly over the last decade to treat various immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and Crohn’s disease[42]. Studies carried out over this period showed that monoclonal antibodies against TNF-α (anti-TNF-α) and high doses of steroid treatment may induce HBV reactivation in patients with overt HBV infection[79-82], thus suggesting the need for anti-HBV pharmacological prophylaxis for inactive HBsAg carriers[83] and treatment for patients with HBsAg-positive chronic hepatitis.

The reactivation of OBI during anti-TNF therapy has not been extensively investigated and the data available are anecdotal and mostly from case reports. In a recent evaluation of the literature data, HBV reactivation was found in only 8 (1.7%) of 468 HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients with rheumatological diseases treated with anti-TNF[82]. In addition, none of 20 HBsAg-negative/HBV DNA-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients receiving anti-TNF-α for rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathy experienced reactivation of OBI during a 4-year follow up[84].

The literature data give evidence of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients treated with chemotherapy for solid tumors[85-87], and, consequently, pharmacological prophylaxis for inactive HBsAg carriers and therapy for patients with HBsAg-positive chronic hepatitis is recommended. Instead, the studies on HBV reactivation in patients with OBI are not conclusive, but so far no evidence of reactivation of OBI in these patients has emerged. The longitudinal study by Saitta et al[88] on 44 HBsAg-negative patients with solid tumors undergoing chemotherapy did not find cases with HBV reactivation. Further prospective studies are needed to improve our knowledge of the clinical importance of OBI in patients with solid cancers.

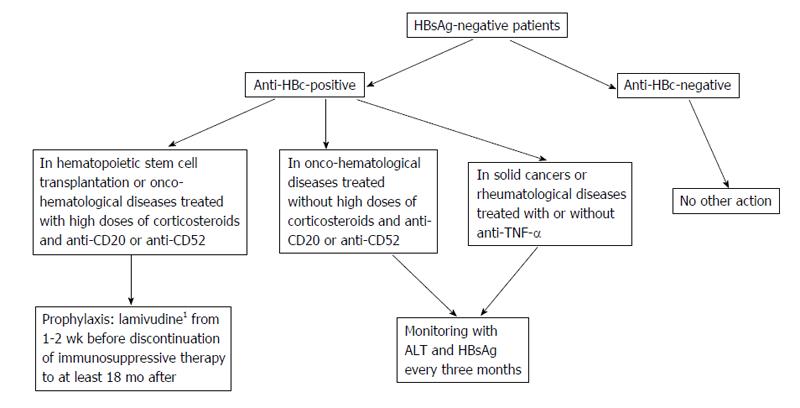

In patients with OBI, pharmacological prophylaxis with nucleot(s)ide analogues should be based on the HBV serological status (anti-HBc-positive or -negative), the underlying diseases (onco-hematological diseases, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or others) and the type of immunosuppressive treatment (rituximab, high doses of corticosteroids, anthracyclines, or others). In anti-HBc-positive patients, the prophylaxis with anti-HBV nucleos(t)ide analogues is indicated in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and in onco-hematological diseases when high doses of corticosteroids and rituximab are used, whereas monitoring is indicated in all other clinical conditions or when rituximab-sparing schedules are used (Figure 2). The literature data have shown the efficacy of lamivudine in preventing HBV reactivation in these subsets of patients[17,43,61]. Also entecavir has been proposed in the prophylaxis of reactivation of OBI. In a randomized controlled trial[89] 80 patients with CD20+ lymphoma and resolved hepatitis B were randomly assigned to a prophylactic schedule with entecavir, started before rituximab-based chemotherapy and stopped 3 mo after its discontinuation, or to be treated with entecavir once HBV reactivation and reversion to HBsAg positivity had occurred (control group). During an 18-mo follow up, HBV reactivation occurred in 2.4% of patients who underwent entecavir prophylaxis and in 17.9% of cases in the control group (P < 0.05).

Although the efficacy of lamivudine and entecavir in preventing the reactivation of OBI has never been compared in published studies, we can conclude, in agreement with current international guidelines[2,76], that lamivudine, despite of its low genetic barrier, remains the nucleos(t)ide analogue of choice for the prophylaxis of reactivation of OBI because of its low cost and of the low or absent HBV viremia in OBI. Instead, entecavir should replace lamivudine for patients with advanced liver diseases for whom reactivation of OBI might be life threatening.

Monitoring of pharmacological prophylaxis is not standardized and the widespread habit of determining HBsAg at three-monthly intervals is not the optimal strategy in all clinical conditions. In addition, it is not fully understood how long the pharmacological prophylaxis should last in order to prevent the reactivation of HBV infection. Observational studies suggest extending the prophylaxis to the 12th month after the discontinuation of immunosuppressive treatment, but in some case reports HBV reactivation occurred later, especially in patients treated with rituximab[39,90]. Recently, Tonziello et al[39] described a reactivation of OBI in an HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive woman with non-Hodgkin lymphoma occurring 20 mo after rituximab discontinuation despite lamivudine prophylaxis covering the 4 mo of rituximab administration and the 12 mo after its discontinuation. Concluding on this point, prospective studies are needed to ascertain whether the pharmacological prophylaxis should be extended to the 18th month after the discontinuation of immunosuppressive treatment in patients receiving rituximab-based chemotherapy.

Once reactivation has occurred, effective antiviral treatment should be immediately administered. Lamivudine monotherapy has been demonstrated to be ineffective in reducing mortality[21]. Consequently, patients should be treated with drugs of high potency and high genetic barrier such as entecavir or tenofovir.

As a consequence of the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which has determined a substantial improvement in the patients’ survival, viral hepatitis has become the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected subjects. In these patients particular attention should be paid to OBI since it may have a strong clinical impact because of damage to the immune system and its frequent occurrence in HIV-HCV coinfected patients.

The prevalence of OBI in HIV-infected patients is controversial, and the associated risk factors and the effect of HAART undefined. Also controversial is the role of the immune system in the genesis of OBI in HIV-positive patients. Some investigators never observed OBI in patients with CD4 counts > 500 cells/μL and concluded for a significant association of OBI with lower CD4 counts[91]. Other investigators, however, described no association of OBI with the CD4 count[92].

The prevalence of OBI in HIV-HCV coinfected patients varies in different studies from less than 1% to 40%[22,93-102].

OBI may also be observed in anti-HIV-positive patients with chronic HBV/HCV coinfection, due to an HBsAg serum clearance consequent to a strong inhibitory effect of the HCV genome on HBV replication[103].

In HIV subjects a strong association between OBI and HCV infection has been observed in several studies[28,101,104-106]. In contrast, Jardim et al[107] reported no significant difference in the rate of OBI in HIV-positive patients with or without HCV coinfection.

The discrepancies in the rate of OBI in the different studies most probably reflect differences in HBV, HCV and HIV epidemiology in different countries, a variation in the sensitivity of the assays used to detect HBV DNA and the retrospective nature of some of the studies.

Cassini et al[108] proposed a new approach to the detection of HBV DNA. By the genomic amplification of the partial S, X and precore/core regions, these Authors analyzed for the presence of HBV DNA the circulating blood, liver tissue and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). HBV DNA was never found in serum samples of the 24 HBsAg-negative patients investigated, but was detected in the liver tissue in 7 (29%) and in PBMC in 6 (86%) of these 7. The clinical value of these data should be confirmed in larger studies, but they suggest that the detection of HBV DNA in PBMC offers a useful tool to identify OBI. Morsica et al[104] analyzed 1593 anti-HIV-positive patients enrolled in the Italian Cohort of Antiretroviral Naïve patients and found 175 (11%) HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients: 27of these 175 (15%) patients had detectable HBV DNA in plasma. This prevalence was significantly higher (21%) in the 101 anti-HCV-positive than in the 74 (8%) anti-HCV-negative, regardless of the immune status, HIV load, or ART regimen.

The impact of OBI on the prognosis of HIV-positive patients is still unclear. In our previous study[22] on the clinical and virological impact of OBI in HIV-positive patients, we analyzed 115 HBsAg-negative patients, 86 of whom were observed in a long-term follow-up. A hepatic flare occurred more frequently in the 17 patients with occult HBV infection than in the 69 without (64.7% vs 24.6%; P < 0.005). These preliminary data still await confirmation in larger studies.

Lamivudine-based HAART is effective in suppressing HBV replication even in anti-HIV-positive patients with OBI, as most of these cases clear HBV DNA during treatment. However, in approximately half of the lamivudine-treated patients, occult HBV replication became detectable again after 12-40 mo of lamivudine treatment, always associated with a hepatic flare. Although the presence of YMDD mutants in patients who became HBV-DNA-positive under lamivudine was not detected, most probably because of the low levels of plasma HBV DNA, the hypothesis that lamivudine induced the selection of YMDD mutants in these anti-HIV-positive subjects with OBI cannot be ruled out. In another study the ALT and aspartate aminotransferase levels showed a tendency to increase more frequently in patients with OBI than in those without[104].

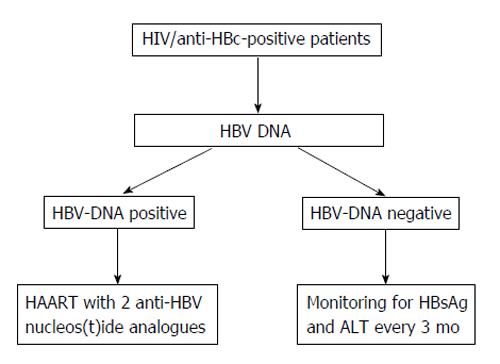

Concluding on this point, OBI seems relatively frequent in anti-HIV-positive patients, particularly in cases with HIV/HCV co-infection. This makes the clinical condition of HIV/HCV co-infection more complex since OBI may unfavorably affect the outcome of the liver disease. Lamivudine seems inadequate for a long-term prevention of hepatic flares in anti-HIV-positive patients with OBI and possibly in reducing the risk of HBV oncogenicity. Therefore, for these patients a high potency, high genetic barrier nucleos(t)ide analogue should be preferred (Figure 3).

Clinicians should pay careful attention to OBI since it has been demonstrated that it occurs with some frequency and may have clinical consequences.

Further studies are needed to better define the biological and clinical role of OBI and to identify new measures to prevent or limit its unfavorable clinical action. It would be of particular benefit to investigate the oncogenicity of OBI, particularly in anti-HIV-positive subjects, in order to devise new strategies for the prevention of HCC.

P- Reviewers: Sutti S, Tsuchiya A S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Lavanchy D. Worldwide epidemiology of HBV infection, disease burden, and vaccine prevention. J Clin Virol. 2005;34 Suppl 1:S1-S3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Murata K, Sugimoto K, Shiraki K, Nakano T. Relative predictive factors for hepatocellular carcinoma after HBeAg seroconversion in HBV infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6848-6852. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Ou DP, Yang LY, Huang GW, Tao YM, Ding X, Chang ZG. Clinical analysis of the risk factors for recurrence of HCC and its relationship with HBV. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2061-2066. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sagnelli E, Stroffolini T, Mele A, Imparato M, Sagnelli C, Coppola N, Almasio PL. Impact of comorbidities on the severity of chronic hepatitis B at presentation. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1616-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Borgia G, Carleo MA, Gaeta GB, Gentile I. Hepatitis B in pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4677-4683. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Torbenson M, Thomas DL. Occult hepatitis B. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:479-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 397] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Izmirli S, Celik DG, Yuksel P, Saribas S, Aslan M, Ergin S, Bahar H, Sen S, Cakal B, Oner A. The detection of occult HBV infection in patients with HBsAg negative pattern by real-time PCR method. Transfus Apher Sci. 2012;47:283-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Coppola N, Loquercio G, Tonziello G, Azzaro R, Pisaturo M, Di Costanzo G, Starace M, Pasquale G, Cacciapuoti C, Petruzziello A. HBV transmission from an occult carrier with five mutations in the major hydrophilic region of HBsAg to an immunosuppressed plasma recipient. J Clin Virol. 2013;58:315-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Raimondo G, Allain JP, Brunetto MR, Buendia MA, Chen DS, Colombo M, Craxì A, Donato F, Ferrari C, Gaeta GB. Statements from the Taormina expert meeting on occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2008;49:652-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 606] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bréchot C, Thiers V, Kremsdorf D, Nalpas B, Pol S, Paterlini-Bréchot P. Persistent hepatitis B virus infection in subjects without hepatitis B surface antigen: clinically significant or purely “occult”. Hepatology. 2001;34:194-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grob P, Jilg W, Bornhak H, Gerken G, Gerlich W, Günther S, Hess G, Hüdig H, Kitchen A, Margolis H. Serological pattern “anti-HBc alone”: report on a workshop. J Med Virol. 2000;62:450-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jilg W, Hottenträger B, Weinberger K, Schlottmann K, Frick E, Holstege A, Schölmerich J, Palitzsch KD. Prevalence of markers of hepatitis B in the adult German population. J Med Virol. 2001;63:96-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Weber B, Melchior W, Gehrke R, Doerr HW, Berger A, Rabenau H. Hepatitis B virus markers in anti-HBc only positive individuals. J Med Virol. 2001;64:312-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hu KQ. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and its clinical implications. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:243-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bréchot C, Jaffredo F, Lagorce D, Gerken G, Meyer zum Büschenfelde K, Papakonstontinou A, Hadziyannis S, Romeo R, Colombo M, Rodes J. Impact of HBV, HCV and GBV-C/HGV on hepatocellular carcinomas in Europe: results of a European concerted action. J Hepatol. 1998;29:173-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Baginski I, Chemin I, Hantz O, Pichoud C, Jullien AM, Chevre JC, Li JS, Vitvitski L, Sninsky JJ, Trepo C. Transmission of serologically silent hepatitis B virus along with hepatitis C virus in two cases of posttransfusion hepatitis. Transfusion. 1992;32:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | dos Santos Ade O, Souza LF, Borzacov LM, Villalobos-Salcedo JM, Vieira DS. Development of cost-effective real-time PCR test: to detect a wide range of HBV DNA concentrations in the western Amazon region of Brazil. Virol J. 2014;11:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jilg W, Sieger E, Zachoval R, Schätzl H. Individuals with antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen as the only serological marker for hepatitis B infection: high percentage of carriers of hepatitis B and C virus. J Hepatol. 1995;23:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NW, Lam WY, Mo FK, Chu MT, Chan HL, Hui EP, Lei KI, Mok TS. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:605-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Coppola N, Tonziello G, Pisaturo M, Messina V, Guastafierro S, Fiore M, Iodice V, Sagnelli C, Stanzione M, Capoluongo N. Reactivation of overt and occult hepatitis B infection in various immunosuppressive settings. J Med Virol. 2011;83:1909-1916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Filippini P, Coppola N, Pisapia R, Scolastico C, Marrocco C, Zaccariello A, Nacca C, Sagnelli C, De Stefano G, Ferraro T. Impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV patients naive for antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2006;20:1253-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Neau D, Winnock M, Jouvencel AC, Faure M, Castéra L, Legrand E, Lacoste D, Ragnaud JM, Dupon M, Fleury H. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-infected patients with isolated antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen: Aquitaine cohort, 2002-2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:750-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Paterlini P, Driss F, Nalpas B, Pisi E, Franco D, Berthelot P, Bréchot C. Persistence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C viral genomes in primary liver cancers from HBsAg-negative patients: a study of a low-endemic area. Hepatology. 1993;17:20-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kubo S, Tamori A, Ohba K, Shuto T, Yamamoto T, Tanaka H, Nishiguchi S, Wakasa K, Hirohashi K, Kinoshita H. Previous or occult hepatitis B virus infection in hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma without hepatic fibrosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2408-2414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sheu JC, Huang GT, Shih LN, Lee WC, Chou HC, Wang JT, Lee PH, Lai MY, Wang CY, Yang PM. Hepatitis C and B viruses in hepatitis B surface antigen-negative hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1322-1327. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Cacciola I, Raffa G, Craxi A, Farinati F, Missale G, Smedile A, Tiribelli C. Hepatitis B virus maintains its pro-oncogenic properties in the case of occult HBV infection. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:102-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Squadrito G, Pollicino T, Cacciola I, Caccamo G, Villari D, La Masa T, Restuccia T, Cucinotta E, Scisca C, Magazzu D. Occult hepatitis B virus infection is associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C patients. Cancer. 2006;106:1326-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Coppola N, Pisapia R, Tonziello G, Martini S, Imparato M, Piai G, Stanzione M, Sagnelli C, Filippini P, Piccinino F. Virological pattern in plasma, peripheral blood mononuclear cells and liver tissue and clinical outcome in chronic hepatitis B and C virus coinfection. Antivir Ther. 2008;13:307-318. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Sagnelli E, Imparato M, Coppola N, Pisapia R, Sagnelli C, Messina V, Piai G, Stanzione M, Bruno M, Moggio G. Diagnosis and clinical impact of occult hepatitis B infection in patients with biopsy proven chronic hepatitis C: a multicenter study. J Med Virol. 2008;80:1547-1553. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Sagnelli E, Pasquale G, Coppola N, Marrocco C, Scarano F, Imparato M, Sagnelli C, Scolastico C, Piccinino F. Liver histology in patients with HBsAg negative anti-HBc and anti-HCV positive chronic hepatitis. J Med Virol. 2005;75:222-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Orlando ME, Raimondo G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sagnelli E, Coppola N, Scolastico C, Mogavero AR, Filippini P, Piccinino F. HCV genotype and “silent” HBV coinfection: two main risk factors for a more severe liver disease. J Med Virol. 2001;64:350-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chemin I, Jeantet D, Kay A, Trépo C. Role of silent hepatitis B virus in chronic hepatitis B surface antigen(-) liver disease. Antiviral Res. 2001;52:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mrani S, Chemin I, Menouar K, Guillaud O, Pradat P, Borghi G, Trabaud MA, Chevallier P, Chevallier M, Zoulim F. Occult HBV infection may represent a major risk factor of non-response to antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1075-1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kitab B, Ezzikouri S, Alaoui R, Nadir S, Badre W, Trepo C, Chemin I, Benjelloun S. Occult HBV infection in Morocco: from chronic hepatitis to hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2014;34:e144-e150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Fukuda R, Ishimura N, Hamamoto S, Moritani M, Uchida Y, Ishihara S, Akagi S, Watanabe M, Kinoshita Y. Co-infection by serologically-silent hepatitis B virus may contribute to poor interferon response in patients with chronic hepatitis C by down-regulation of type-I interferon receptor gene expression in the liver. J Med Virol. 2001;63:220-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sagnelli E, Coppola N, Scolastico C, Mogavero AR, Stanzione M, Filippini P, Felaco FM, Piccinino F. Isolated anti-HBc in chronic hepatitis C predicts a poor response to interferon treatment. J Med Virol. 2001;65:681-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Tonziello G, Pisaturo M, Sica A, Ferrara MG, Sagnelli C, Pasquale G, Sagnelli E, Guastafierro S, Coppola N. Transient reactivation of occult hepatitis B virus infection despite lamivudine prophylaxis in a patient treated for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Infection. 2013;41:225-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Coppola N, Gentile I, Pasquale G, Buonomo AR, Capoluongo N, D’Armiento M, Borgia G, Sagnelli E. Anti-HBc positivity was associated with histological cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:20-26. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Jang JY, Park EJ. [Occult hepatitis B virus infection in chronic hepatitis C]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2013;62:154-159. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Mastroianni CM, Lichtner M, Citton R, Del Borgo C, Rago A, Martini H, Cimino G, Vullo V. Current trends in management of hepatitis B virus reactivation in the biologic therapy era. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3881-3887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Yeo W, Johnson PJ. Diagnosis, prevention and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation during anticancer therapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:209-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lau GK. Hepatitis B reactivation after chemotherapy: two decades of clinical research. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:152-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lubel JS, Angus PW. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy: diagnosis and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:864-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Watanabe T, Tanaka Y. Reactivation of hepatitis viruses following immunomodulating systemic chemotherapy. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Yağci M, Acar K, Sucak GT, Aki Z, Bozdayi G, Haznedar R. A prospective study on chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation in chronic HBs Ag carriers with hematologic malignancies and pre-emptive therapy with nucleoside analogues. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1608-1612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Fukushima N, Mizuta T, Tanaka M, Yokoo M, Ide M, Hisatomi T, Kuwahara N, Tomimasu R, Tsuneyoshi N, Funai N. Retrospective and prospective studies of hepatitis B virus reactivation in malignant lymphoma with occult HBV carrier. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:2013-2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Pei SN, Chen CH, Lee CM, Wang MC, Ma MC, Hu TH, Kuo CY. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus following rituximab-based regimens: a serious complication in both HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative patients. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:255-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Palmore TN, Shah NL, Loomba R, Borg BB, Lopatin U, Feld JJ, Khokhar F, Lutchman G, Kleiner DE, Young NS. Reactivation of hepatitis B with reappearance of hepatitis B surface antigen after chemotherapy and immunosuppression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1130-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Lalazar G, Rund D, Shouval D. Screening, prevention and treatment of viral hepatitis B reactivation in patients with haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:699-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Kusumoto S, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Ueda R. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus following systemic chemotherapy for malignant lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2009;90:13-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Liang R. How I treat and monitor viral hepatitis B infection in patients receiving intensive immunosuppressive therapies or undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113:3147-3153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Ustün C, Koç H, Karayalcin S, Akyol G, Gürman G, Ilhan O, Akan H, Ozcan M, Arslan O, Konuk N. Hepatitis B virus infection in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;20:289-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Lau GK, Leung YH, Fong DY, Au WY, Kwong YL, Lie A, Hou JL, Wen YM, Nanj A, Liang R. High hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA viral load as the most important risk factor for HBV reactivation in patients positive for HBV surface antigen undergoing autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2002;99:2324-2330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Ma SY, Lau GK, Cheng VC, Liang R. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients positive for hepatitis B surface antigen undergoing autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:1281-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Knöll A, Boehm S, Hahn J, Holler E, Jilg W. Reactivation of resolved hepatitis B virus infection after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:925-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Hui CK, Sun J, Au WY, Lie AK, Yueng YH, Zhang HY, Lee NP, Hou JL, Liang R, Lau GK. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in hematopoietic stem cell donors in a hepatitis B virus endemic area. J Hepatol. 2005;42:813-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Onozawa M, Hashino S, Izumiyama K, Kahata K, Chuma M, Mori A, Kondo T, Toyoshima N, Ota S, Kobayashi S. Progressive disappearance of anti-hepatitis B surface antigen antibody and reverse seroconversion after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with previous hepatitis B virus infection. Transplantation. 2005;79:616-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Aksoy S, Harputluoglu H, Kilickap S, Dede DS, Dizdar O, Altundag K, Barista I. Rituximab-related viral infections in lymphoma patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1307-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Francisci D, Falcinelli F, Schiaroli E, Capponi M, Belfiori B, Flenghi L, Baldelli F. Management of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with hematological malignancies treated with chemotherapy. Infection. 2010;38:58-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Borentain P, Colson P, Coso D, Bories E, Charbonnier A, Stoppa AM, Auran T, Loundou A, Motte A, Ressiot E. Clinical and virological factors associated with hepatitis B virus reactivation in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc antibodies-positive patients undergoing chemotherapy and/or autologous stem cell transplantation for cancer. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:807-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Sugauchi F, Tanaka Y, Kusumoto S, Matsuura K, Sugiyama M, Kurbanov F, Ueda R, Mizokami M. Virological and clinical characteristics on reactivation of occult hepatitis B in patients with hematological malignancy. J Med Virol. 2011;83:412-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Elkady A, Aboulfotuh S, Ali EM, Sayed D, Abdel-Aziz NM, Ali AM, Murakami S, Iijima S, Tanaka Y. Incidence and characteristics of HBV reactivation in hematological malignant patients in south Egypt. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6214-6220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Hui CK, Cheung WW, Zhang HY, Au WY, Yueng YH, Leung AY, Leung N, Luk JM, Lie AK, Kwong YL. Kinetics and risk of de novo hepatitis B infection in HBsAg-negative patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:59-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Li JM, Wang L, Shen Y, Xia ZG, Chen Y, Chen QS, Chen Y, Zeng XY, You JH, Qian Y. Rituximab in combination with CHOP chemotherapy for the treatment of diffuse large B cell lymphoma in Chinese patients. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:639-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Targhetta C, Cabras MG, Mamusa AM, Mascia G, Angelucci E. Hepatitis B virus-related liver disease in isolated anti-hepatitis B-core positive lymphoma patients receiving chemo- or chemo-immune therapy. Haematologica. 2008;93:951-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Hanbali A, Khaled Y. Incidence of hepatitis B reactivation following Rituximab therapy. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Matsue K, Kimura S, Takanashi Y, Iwama K, Fujiwara H, Yamakura M, Takeuchi M. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus after rituximab-containing treatment in patients with CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2010;116:4769-4776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Hsu C, Tsou HH, Lin SJ, Wang MC, Yao M, Hwang WL, Kao WY, Chiu CF, Lin SF, Lin J. Chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B reactivation in lymphoma patients with resolved HBV infection: A prospective study. Hepatology. 2014;59:2092-2100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Matsui T, Kang JH, Nojima M, Tomonari A, Aoki H, Yamazaki H, Yane K, Tsuji K, Andoh S, Andoh S. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus in patients with undetectable HBsAg undergoing chemotherapy for malignant lymphoma or multiple myeloma. J Med Virol. 2013;85:1900-1906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Koo YX, Tan DS, Tan IB, Tao M, Chow WC, Lim ST. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and role of antiviral prophylaxis in lymphoma patients with past hepatitis B virus infection who are receiving chemoimmunotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Ji D, Cao J, Hong X, Li J, Wang J, Chen F, Wang C, Zou S. Low incidence of hepatitis B virus reactivation during chemotherapy among diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients who are HBsAg-negative/ HBcAb-positive: a multicenter retrospective study. Eur J Haematol. 2010;85:243-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Koo YX, Tay M, Teh YE, Teng D, Tan DS, Tan IB, Tai DW, Quek R, Tao M, Lim ST. Risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in hepatitis B surface antigen negative/hepatitis B core antibody positive patients receiving rituximab-containing combination chemotherapy without routine antiviral prophylaxis. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:1219-1223. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Kim SJ, Hsu C, Song YQ, Tay K, Hong XN, Cao J, Kim JS, Eom HS, Lee JH, Zhu J. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in B-cell lymphoma patients treated with rituximab: analysis from the Asia Lymphoma Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3486-3496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Marzano A, Angelucci E, Andreone P, Brunetto M, Bruno R, Burra P, Caraceni P, Daniele B, Di Marco V, Fabrizi F. Prophylaxis and treatment of hepatitis B in immunocompromised patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:397-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507-539. [PubMed] |

| 78. | Dong HJ, Ni LN, Sheng GF, Song HL, Xu JZ, Ling Y. Risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients receiving rituximab-chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Clin Virol. 2013;57:209-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Zingarelli S, Frassi M, Bazzani C, Scarsi M, Puoti M, Airò P. Use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-blocking agents in hepatitis B virus-positive patients: reports of 3 cases and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1188-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Tamori A, Koike T, Goto H, Wakitani S, Tada M, Morikawa H, Enomoto M, Inaba M, Nakatani T, Hino M. Prospective study of reactivation of hepatitis B virus in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who received immunosuppressive therapy: evaluation of both HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative cohorts. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:556-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Kim YJ, Bae SC, Sung YK, Kim TH, Jun JB, Yoo DH, Kim TY, Sohn JH, Lee HS. Possible reactivation of potential hepatitis B virus occult infection by tumor necrosis factor-alpha blocker in the treatment of rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:346-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Lee YH, Bae SC, Song GG. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in rheumatic patients with hepatitis core antigen (HBV occult carriers) undergoing anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31:118-121. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Nathan DM, Angus PW, Gibson PR. Hepatitis B and C virus infections and anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy: guidelines for clinical approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1366-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Biondo MI, Germano V, Pietrosanti M, Canzoni M, Marignani M, Stroffolini T, Salemi S, D’Amelio R. Lack of hepatitis B virus reactivation after anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment in potential occult carriers with chronic inflammatory arthropathies. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:482-484. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Yeo W, Chan HL. Hepatitis B virus reactivation associated with anti-neoplastic therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:31-37. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Yeo W, Zee B, Zhong S, Chan PK, Wong WL, Ho WM, Lam KC, Johnson PJ. Comprehensive analysis of risk factors associating with Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1306-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Yeo W, Chan PK, Hui P, Ho WM, Lam KC, Kwan WH, Zhong S, Johnson PJ. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in breast cancer patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study. J Med Virol. 2003;70:553-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Saitta C, Musolino C, Marabello G, Martino D, Leonardi MS, Pollicino T, Altavilla G, Raimondo G. Risk of occult hepatitis B virus infection reactivation in patients with solid tumours undergoing chemotherapy. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:683-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Huang YH, Hsiao LT, Hong YC, Chiou TJ, Yu YB, Gau JP, Liu CY, Yang MH, Tzeng CH, Lee PC. Randomized controlled trial of entecavir prophylaxis for rituximab-associated hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with lymphoma and resolved hepatitis B. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2765-2772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Garcia-Rodriguez MJ, Canales MA, Hernandez-Maraver D, Hernandez-Navarro F. Late reactivation of resolved hepatitis B virus infection: an increasing complication post rituximab-based regimens treatment. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:673-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Cohen Stuart JW, Velema M, Schuurman R, Boucher CA, Hoepelman AI. Occult hepatitis B in persons infected with HIV is associated with low CD4 counts and resolves during antiretroviral therapy. J Med Virol. 2009;81:441-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Nebbia G, Garcia-Diaz A, Ayliffe U, Smith C, Dervisevic S, Johnson M, Gilson R, Tedder R, Geretti AM. Predictors and kinetics of occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-infected persons. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1464-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Rodríguez-Torres M, Gonzalez-Garcia J, Bräu N, Solá R, Moreno S, Rockstroh J, Smaill F, Mendes-Correa MC, DePamphilis J, Torriani FJ. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in the setting of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection: clinically relevant or a diagnostic problem. J Med Virol. 2007;79:694-700. [PubMed] |

| 94. | Pogány K, Zaaijer HL, Prins JM, Wit FW, Lange JM, Beld MG. Occult hepatitis B virus infection before and 1 year after start of HAART in HIV type 1-positive patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21:922-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Quarleri J, Moretti F, Bouzas MB, Laufer N, Carrillo MG, Giuliano SF, Pérez H, Cahn P, Salomon H. Hepatitis B virus genotype distribution and its lamivudine-resistant mutants in HIV-coinfected patients with chronic and occult hepatitis B. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:525-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Piroth L, Carrat F, Larrat S, Goderel I, Martha B, Payan C, Lunel-Fabiani F, Bani-Sadr F, Perronne C, Cacoub P. Prevalence and impact of GBV-C, SEN-V and HBV occult infections in HIV-HCV co-infected patients on HCV therapy. J Hepatol. 2008;49:892-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Lo Re V, Frank I, Gross R, Dockter J, Linnen JM, Giachetti C, Tebas P, Stern J, Synnestvedt M, Localio AR. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes for occult hepatitis B virus infection among HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:315-320. [PubMed] |

| 98. | Mphahlele MJ, Lukhwareni A, Burnett RJ, Moropeng LM, Ngobeni JM. High risk of occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-positive patients from South Africa. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Raffa G, Maimone S, Cargnel A, Santantonio T, Antonucci G, Massari M, Schiavini M, Caccamo G, Pollicino T, Raimondo G. Analysis of occult hepatitis B virus infection in liver tissue of HIV patients with chronic hepatitis C. AIDS. 2007;21:2171-2175. [PubMed] |

| 100. | Castro P, Laguno M, Nomdedeu M, López A, Plana M, Fumero E, Gallart T, Mallolas J, Gatell JM, García F. Clinicoimmunological progression and response to treatment of long-term nonprogressor HIV-hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:863-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Fabris P, Biasin MR, Giordani MT, Berardo L, Menini V, Carlotto A, Miotti MG, Manfrin V, Baldo V, Nebbia G. Impact of occult HBV infection in HIV/HCV co-infected patients: HBV-DNA detection in liver specimens and in serum samples. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6:173-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Ramezani A, Mohraz M, Aghakhani A, Banifazl M, Eslamifar A, Khadem-Sadegh A, Velayati AA. Frequency of isolated hepatitis B core antibody in HIV-hepatitis C virus co-infected individuals. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:336-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Filippini P, Coppola N, Pisapia R, Martini S, Marrocco C, Di Martino F, Sagnelli C, Filippini A, Sagnelli E. Virological and clinical aspects of HBV-HCV coinfection in HIV positive patients. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1679-1685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Morsica G, Ancarani F, Bagaglio S, Maracci M, Cicconi P, Cozzi Lepri A, Antonucci G, Bruno R, Santantonio T, Tacconi L. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in a cohort of HIV-positive patients: correlation with hepatitis C virus coinfection, virological and immunological features. Infection. 2009;37:445-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Ikeda K, Marusawa H, Osaki Y, Nakamura T, Kitajima N, Yamashita Y, Kudo M, Sato T, Chiba T. Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen and risk for hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:649-656. [PubMed] |

| 106. | Marque-Juillet S, Touzard A, Monnier S, Fernand-Laurent C, Therby A, Rigaudeau S, Harzic M. [Evaluation of cytomegalovirus quantification in blood by the R-gene real-time PCR test]. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2010;58:162-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Jardim RN, Gonçales NS, Pereira JS, Fais VC, Gonçales Junior FL. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in immunocompromised patients. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12:300-305. [PubMed] |

| 108. | Cassini R, De Mitri MS, Gibellini D, Urbinati L, Bagaglio S, Morsica G, Domenicali M, Verucchi G, Bernardi M. A novel stop codon mutation within the hepatitis B surface gene is detected in the liver but not in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of HIV-infected individuals with occult HBV infection. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:42-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |