Published online Apr 27, 2023. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v15.i4.564

Peer-review started: January 7, 2023

First decision: February 21, 2023

Revised: February 24, 2023

Accepted: March 27, 2023

Article in press: March 27, 2023

Published online: April 27, 2023

Processing time: 102 Days and 8.4 Hours

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is frequently seen in patients with liver cirrhosis. However, current lite

To identify trends and clinical outcomes of PUD in NAFLD hospitalizations in the United States.

The National Inpatient Sample was utilized to identify all adult (≥ 18 years old) NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD in the United States from 2009-2019. Hospitalization trends and outcomes were highlighted. Furthermore, a control group of adult PUD hospitalizations without NAFLD was also identified for a comparative analysis to assess the influence of NAFLD on PUD.

The total number of NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD increased from 3745 in 2009 to 3805 in 2019. We noted an increase in the mean age for the study population from 56 years in 2009 to 63 years in 2019 (P < 0.001). Racial differences were also prevalent as NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD increased for Whites and Hispanics, while a decline was observed for Blacks and Asians. The all-cause inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD increased from 2% in 2009 to 5% in 2019 (P < 0.001). However, rates of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and upper endoscopy decreased from 5% in 2009 to 1% in 2019 (P < 0.001) and from 60% in 2009 to 19% in 2019 (P < 0.001), respectively. Interestingly, despite a significantly higher comorbidity burden, we observed lower inpatient mortality (2% vs 3%, P = 0.0004), mean length of stay (LOS) (11.6 vs 12.1 d, P < 0.001), and mean total healthcare cost (THC) ($178598 vs $184727, P < 0.001) for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD compared to non-NAFLD PUD hospitalizations. Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract, coagulopathy, alcohol abuse, malnutrition, and fluid and electrolyte disorders were identified to be independent predictors of inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD.

Inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD increased for the study period. Howe

Core Tip: Due to dietary and lifestyle changes, the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is on the rise worldwide. Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is commonly seen in patients with liver cirrhosis. However, data on PUD in NAFLD hospitalizations is currently lacking. In this study, we noted an increase in inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD in the United States. The rates of Helicobacter pylori infection and upper endoscopy for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD were on the decline. Despite a higher comorbidity burden, inpatient mortality, mean length of stay, and mean total healthcare cost were lower for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD compared to the non-NAFLD cohort.

- Citation: Dahiya DS, Jahagirdar V, Ali H, Gangwani MK, Aziz M, Chandan S, Singh A, Perisetti A, Soni A, Inamdar S, Sanaka MR, Al-Haddad M. Peptic ulcer disease in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease hospitalizations: A new challenge on the horizon in the United States. World J Hepatol 2023; 15(4): 564-576

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v15/i4/564.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v15.i4.564

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) encompasses a wide range of conditions primarily characterized by the presence of hepatic steatosis which is identified on radiological imaging or histology after other secondary causes of fat deposition have been excluded[1]. Based on histological findings, it is further subdivided into NAFL, which is hepatic steatosis without hepatocellular injury, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) characterized by hepatic steatosis and inflammation with hepatocyte injury. NAFLD usually progresses linearly from steatosis and hepatitis to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and ultimately hepatocellular carcinoma. Risk factors commonly implicated in the development of NAFLD include obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, and metabolic syndrome[2]. The global prevalence of NAFLD is estimated to be 25% and is expected to rise further due to the rising incidence and prevalence of obesity worldwide[3]. In the United States, approximately 80 million people have NAFLD, with NASH being the second leading cause of liver transplant[4].

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) involves acid-induced mucosal disruption in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, usually in the stomach or proximal duodenum. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and the excessive use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the leading causes of PUD[5]. Additionally, increasing age, smoking, alcohol use, and obesity have a strong association with PUD[6]. Although the prevalence of self-reported physician-diagnosed ulcer disease in the United States was as high as 10% at the end of the 20th century, there has been a decrease in prevalence and hospitalizations for PUD in the last few decades, primarily due to advancements in H. pylori eradication and increasing utilization of proton pump inhibitors for acid suppression[7,8].

The association between alcoholic liver disease and PUD has been well established with studies reporting a higher prevalence of PUD in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis[9]. Additionally, a study by Nojkov and Cappell noted that PUD was the most common cause of non-variceal hemorrhage in cirrhotics and carried a higher rate of re-bleeding, delayed ulcer healing, and recurrence when compared to the general population[10]. However, there continue to be significant knowledge gaps on PUD in NAFLD hospitalizations. Hence, we addressed the knowledge gaps in current literature as we identified hospitalization trends, outcomes, and predictors of mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD. Furthermore, we also performed a comparative analysis between NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD and non-NAFLD PUD hospitalizations to determine the influence of NALFD on PUD.

The study cohort was derived from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database which is one of the largest, publicly available, multi-ethnic databases in the United States. The NIS, part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project group of databases, consists of data on inpatient admissions submitted by hospitals across the United States to state-wide data organizations, covering 97% of the United States population[11]. It approximates a 20-percent stratified sample, and the dataset is weighted to obtain national estimates[12]. For the 2009-2019 study period, the NIS database was coded using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9/10 coding systems.

We utilized the NIS to obtain all adult (≥ 18 years) NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD in the United States from 2009-2019. Furthermore, a control group of all adult PUD hospitalizations without NAFLD were identified for comparative analysis.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) while accounting for the weights in the stratified survey design. The weights were considered during statistical estimation by incorporating variables for strata, clusters, and weight to discharges in the NIS. Descriptive statistics were provided, including mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and count (percentage) for categorical variables. To test for the trend for proportions of binary variables in years, the Cochran-Armitage trend test was implemented. The trend for the averages of continuous variables in years was examined using linear regression. The Rao-Scott design-adjusted chi-square test, which takes the stratified survey design into account, examined the association between two categorical variables. All analytical results were statistically significant when the P-values ≤ 0.05.

The NIS database lacks any patient and hospital-specific identifiers. Hence, this study was exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review as per guidelines put forth by our institutional IRB for research on database studies.

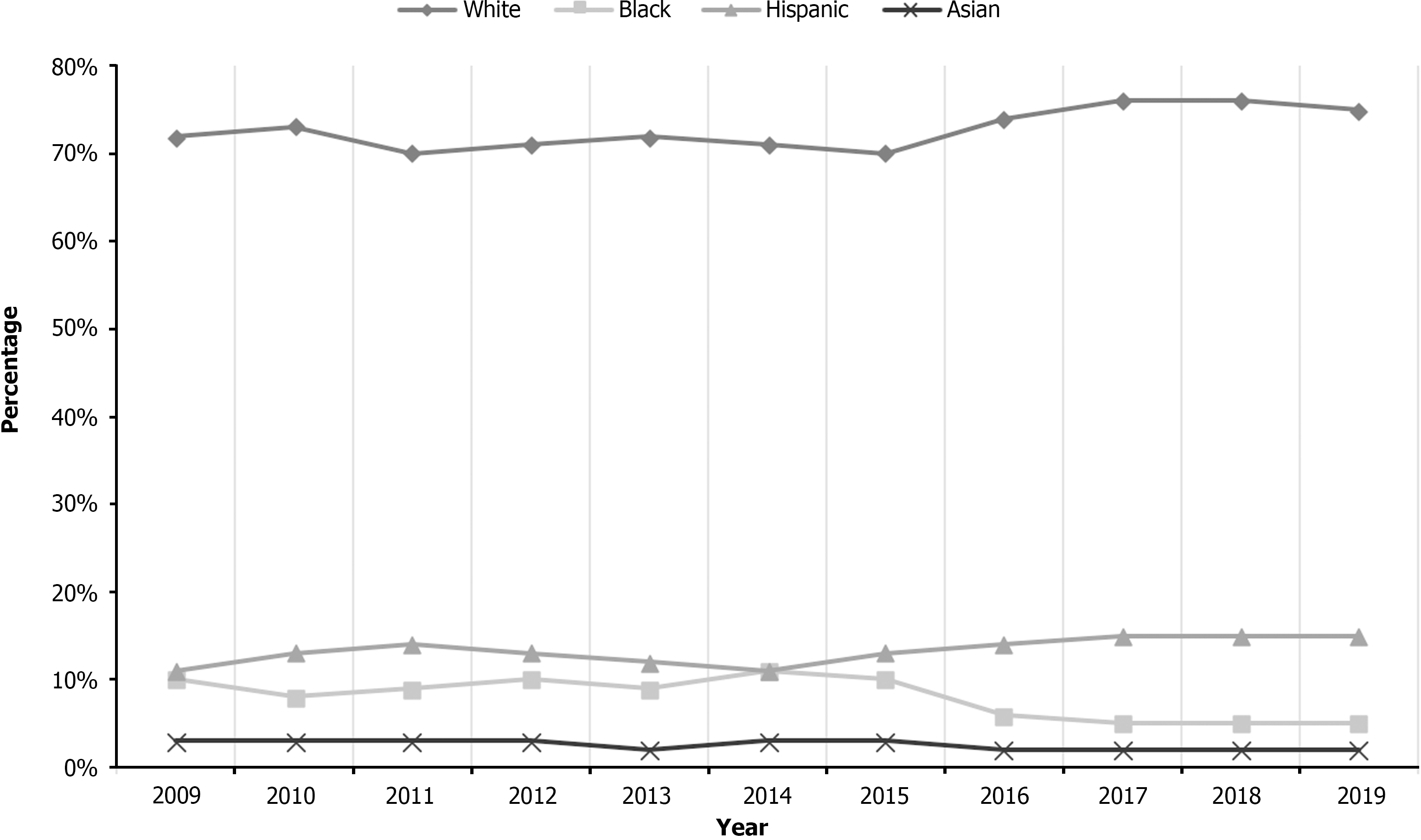

Overall, there was no decline in the total number of NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD (3745 in 2009 to 3805 in 2019, with a peak of 6885 in 2014) (Table 1). The mean age increased from 56.0 years in 2009 to 63.0 years in 2019 (P < 0.001), with a significant increase noted for the 65-79 age group (26% in 2009 to 46% in 2019). A majority of NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD were for females and Whites. Racial differences were also noted as there was a declining trend of NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD for Blacks from 10% in 2009 to 5% in 2019 (P = 0.01) and Asians from 3% in 2009 to 2% in 2019 (P = 0.01), while Whites and Hispanics had a rising trend (Table 1 and Figure 1). Furthermore, rates of H. pylori infection and upper endoscopy decreased from 2009 to 2019 (Table 1). Most NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD were at large hospitals, and admissions in urban teaching hospitals increased from 40% in 2009 to 80% in 2019 (P < 0.001). Overall, Medicare was the largest insurer for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD.

| Variable | Years | |||||||||

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Total hospitalizations | 3745 | 4563 | 5230 | 5655 | 5759 | 6885 | 5745 | 2880 | 3070 | 3430 |

| Mean age (yr) | 56.01 ± 0.8 | 57.07 ± 0.75 | 56.68 ± 0.81 | 57.1 ± 0.14 | 57.1 ± 0.41 | 57.4 ± 0.59 | 57.5 ± 0.97 | 62.4 ± 0.41 | 62.8 ± 0.8 | 63.7 ± 0.74 |

| Age groups, yr (%) | ||||||||||

| 18-34 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| 35-49 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 12 | 11 | 15 |

| 50-64 | 39 | 42 | 41 | 39 | 42 | 42 | 39 | 44 | 40 | 36 |

| 65-79 | 26 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 28 | 32 | 42 | 44 | 47 |

| ≥ 80 | < 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Gender (%) | ||||||||||

| Male | 45 | 42 | 43 | 43 | 44 | 44 | 45 | 36 | 40 | 40 |

| Female | 55 | 48 | 57 | 58 | 56 | 56 | 55 | 64 | 60 | 50 |

| Race (%) | 0.01 | |||||||||

| White | 72 | 73 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 71 | 70 | 74 | 76 | 76 |

| Black | 10 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Hispanic | 11 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 15 |

| Asian | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Native American | 1 | < 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| CCI (%) | ||||||||||

| CCI = 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CCI = 1 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 32 | 32 | 31 | 31 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| CCI = 2 | 27 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 25 | 13 | 8 | 10 |

| CCI ≥ 3 | 39 | 44 | 43 | 47 | 46 | 47 | 44 | 86 | 86 | 86 |

| Hospital region (%) | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 13 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 16 |

| Midwest | 24 | 24 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 28 | 29 | 29 |

| South | 39 | 41 | 43 | 21 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 38 | 37 | 35 |

| West | 24 | 23 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 21 | 19 |

| Hospital bed-size (%) | ||||||||||

| Small | 8 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 16 |

| Medium | 25 | 25 | 22 | 29 | 26 | 32 | 29 | 24 | 25 | 28 |

| Large | 67 | 64 | 67 | 59 | 63 | 52 | 55 | 61 | 59 | 56 |

| Hospital location and teaching status (%) | ||||||||||

| Rural | 8 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Urban non-teaching | 47 | 50 | 45 | 41 | 37 | 26 | 27 | 21 | 20 | 14 |

| Urban teaching | 46 | 40 | 44 | 49 | 53 | 67 | 66 | 73 | 75 | 81 |

| Primary payer | ||||||||||

| Medicare | 41 | 42 | 41 | 44 | 43 | 44 | 44 | 53 | 60 | 60 |

| Medicaid | 13 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 11 | 11 |

| Private | 36 | 35 | 35 | 33 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 30 | 25 | 26 |

| Other | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Median household income (%) | ||||||||||

| 1st (0-25th) | 26 | 27 | 30 | 28 | 31 | 28 | 31 | 31 | 27 | 29 |

| 2nd (26th-50th) | 25 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 26 | 29 | 24 | 27 | 32 | 32 |

| 3rd (51st-75th) | 30 | 24 | 24 | 26 | 24 | 23 | 26 | 24 | 25 | 21 |

| 4th (76th-100th) | 19 | 24 | 21 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 17 | 15 | 18 |

| Upper endoscopy (%) | 60 | 59 | 62 | 58 | 59 | 59 | 62 | 20 | 22 | 18 |

We noted a rising trend of all-cause inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD from 2% in 2009 to 5% in 2019 (P < 0.001) (Table 2). However, inpatient mortality for Whites declined from 81% in 2009 to 64% in 2019 (P = 0.04) within the race analysis. We did not find a statistically significant trend for mean length of stay (LOS) and mean total healthcare cost (THC). Furthermore, the rates of GI tract perforation decreased [33% (2009) to 8% (2019), P = 0.02] but the proportion of patients with GI bleeding increased [0% (2009) to 11% (2019), P = 0.04].

| Outcome | Years | Pvalue | ||||||||||

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| Inpatient mortality (%) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | < 0.001 |

| Gender-specific inpatient mortality (%) | 0.2 | |||||||||||

| Male | 25 | 21 | 28 | 57 | 53 | 38 | 40 | 37 | 52 | 32 | 31 | |

| Female | 75 | 79 | 72 | 43 | 47 | 62 | 60 | 63 | 48 | 48 | 48 | |

| Race-specific inpatient mortality (%) | 0.4 | |||||||||||

| White | 81 | 53 | 89 | 48 | 79 | 73 | 73 | 71 | 81 | 61 | 64 | |

| Black | 7 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 11 | |

| Hispanic | 12 | 47 | 11 | 19 | 16 | 19 | 7 | 17 | 8 | 19 | 14 | |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 6 | |

| Native American | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 6 | |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 0 | |

| Age-group specific inpatient mortality (%) | 0.1 | |||||||||||

| 18-34 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 35-49 | 13 | 26 | 16 | 13 | 0 | 17 | 14 | 9 | 22 | 14 | 6 | |

| 50-64 | 51 | 36 | 33 | 31 | 29 | 34 | 36 | 41 | 52 | 31 | 48 | |

| 65-79 | 28 | 24 | 36 | 56 | 71 | 41 | 50 | 50 | 26 | 48 | 45 | |

| ≥ 80 | 0 | 13 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Length of stay (d) | 17.1 ± 0.59 | 11.8 ± 0.76 | 16.3 ± 0.58 | 9.2 ± 0.85 | 9.0 ± 0.01 | 8.2 ± 0.68 | 10.1 ± 0.33 | 9.6 ± 0.49 | 17.3 ± 0.33 | 9.2 ± 0.90 | 11.2 ± 0.22 | 0.06 |

| Total hospital charge ($) | 182296 ± 760 | 104265 ± 620 | 215085 ± 130 | 172837 ± 170 | 157079 ± 890 | 105031 ± 760 | 136876 ± 800 | 134573 ± 730 | 373045 ± 450 | 143284 ± 940 | 174044 ± 550 | 0.8 |

| Complications (%) | ||||||||||||

| Bleeding | 0 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 17 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 0.4 |

| Perforation | 33 | 12 | 35 | 29 | 16 | 3 | 13 | 17 | 11 | 3 | 8 | 0.02 |

NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD were younger (58.6 vs 65.3 years, P < 0.001), and had more Whites and Hispanics compared to the non-NAFLD subgroup (Table 3). A Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) ≥ 3 was noted in a higher proportion of NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD (55%) compared to non-NAFLD PUD hospitalizations (49%) (P < 0.001). Although NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD had a higher proportion of patients that underwent upper endoscopy (49% vs 41%, P < 0.001), the rates of H. pylori infection was not statistically different between the cohorts (Table 3).

| NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD | Non-NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD | P value | |

| Total hospitalizations | 50769 (1%) | 4624628 (99%) | |

| Mean age (yr) | 58.6 ± 0.27 | 65.3 ± 0. 80 | < 0.001 |

| Age group, yr (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| 18-34 | 6 | 6 | |

| 35-49 | 21 | 15 | |

| 50-64 | 40 | 33 | |

| 65-79 | 32 | 40 | |

| ≥ 80 | 1 | 6 | |

| Gender (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 42 | 49 | |

| Female | 48 | 51 | |

| Race (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| White | 72 | 70 | |

| Black | 9 | 14 | |

| Hispanic | 13 | 9 | |

| Asian | 3 | 3 | |

| Native American | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 3 | 3 | |

| CCI (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| CCI = 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CCI = 1 | 25 | 30 | |

| CCI = 2 | 20 | 22 | |

| CCI ≥ 3 | 55 | 49 | |

| Upper endoscopy (%) | 49 | 41 | < 0.001 |

| H. pylori (%) | 3 | 3 | 0.5 |

| Hospital region (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Northeast | 14 | 18 | |

| Midwest | 24 | 23 | |

| South | 41 | 39 | |

| West | 21 | 20 | |

| Hospital bed size (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Small | 14 | 16 | |

| Medium | 27 | 28 | |

| Large | 59 | 56 | |

| Hospital location and teaching status (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Rural | 8 | 10 | |

| Urban nonteaching | 32 | 34 | |

| Urban teaching | 60 | 56 | |

| Expected primary payer (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 47 | 61 | |

| Medicaid | 14 | 12 | |

| Private | 32 | 21 | |

| Other | 7 | 5 | |

| Median household income (quartile) (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| 1st (0-25th) | 29 | 31 | |

| 2nd (26th-50th) | 27 | 26 | |

| 3rd (51st-75th) | 25 | 24 | |

| 4th (76th-100th) | 20 | 19 |

Despite a higher CCI score, the all-cause inpatient mortality was lower (2% vs 3%, P = 0.0004), for NAFLD-PUD hospitalizations compared to the non-NAFLD-PUD hospitalizations (Table 4). Furthermore, the mean LOS was shorter (11.6 vs 12.1 d, P < 0.001), the and mean THC was lower ($178598 and $184727, P < 0.001) for NAFLD-PUD hospitalizations compared to non-NAFLD-PUD hospitalizations (Table 4). There was no statistical difference in the proportion of patients with complications such as GI bleeding and perforation between the 2 groups.

| Outcomes | NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD | Non-NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD | P value |

| Inpatient mortality (%) | 2 | 3 | 0.0004 |

| Gender-specific inpatient mortality (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 38 | 54 | |

| Female | 62 | 46 | |

| Race-specific inpatient mortality (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| White | 70 | 72 | |

| Black | 6 | 12 | |

| Hispanic | 16 | 9 | |

| Asian | 3 | 4 | |

| Native American | 3 | 1 | |

| Others | 3 | 3 | |

| Age-group specific inpatient mortality (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| 18-34 | 1 | 2 | |

| 35-49 | 13 | 7 | |

| 50-64 | 39 | 30 | |

| 65-79 | 44 | 49 | |

| ≥ 80 | 2 | 12 | |

| Length of stay (d) | 11.6 | 12.1 | < 0.001 |

| Total healthcare cost ($) | 178598 | 184727 | < 0.001 |

| Complications (%) | |||

| Bleeding | 8 | 6 | 0.2 |

| Perforations | 14 | 18 | 0.1 |

Significant predictors of all-cause inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD included GI tract perforation (aHR = 2.71, 95%CI: 1.37-5.35, P = 0.004), coagulopathy (aHR = 2.24, 95%CI: 0.74-0.84, P < 0.001), fluid and electrolyte disorders (aHR = 1.92, 95%CI: 1.82-2.01, P < 0.001), alcohol abuse (aHR = 1.51, 95%CI: 1.42-1.61, P < 0.001), and protein-calorie malnutrition (aHR = 1.16, 95%CI: 1.11-1.22, P < 0.001) (Table 5).

| Variable | Adjusted hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value |

| Coagulopathy | 2.24 | 2.14-2.34 | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 0.79 | 0.74-0.84 | < 0.001 |

| Protein calorie malnutrition | 1.16 | 1.11-1.22 | < 0.001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorder | 1.92 | 1.82-2.01 | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.51 | 1.42-1.61 | < 0.001 |

| Perforation | 2.71 | 1.37-5.35 | 0.004 |

PUD is believed to be the most common cause of non-variceal GI bleeding in liver cirrhosis patients. However, data on PUD in NAFLD hospitalizations is lacking. Ours is the only study in current literature that evaluates the trends of hospitalization characteristics and outcomes for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD and further compares NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD to non-NAFLD PUD hospitalizations using the NIS database. In this study, we did not find a decline in the total number of NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD. The all-cause inpatient mortality increased from 2% in 2009 to 5% in 2019 in the United States. However, the rates of upper endoscopy and H. pylori infection declined for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD. Furthermore, NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD had lower mortality, LOS, and THC compared to the non-NAFLD group, despite a higher comorbidity burden. An understanding of the trends, outcomes, and influence of NAFLD on PUD is crucial as it may help gastroenterologists identify individuals at the greatest risk of adverse outcomes and complications, thereby preventing morbidity and mortality.

Recent studies have demonstrated a dramatic increase in the prevalence and hospitalization rates for patients with NAFLD, which could have led to the slightly increased number of hospitalizations noted in our study[13,14]. This is despite the fact that there has been an overall decline in hospitalization rates for PUD in the United States[15]. Furthermore, racial differences have also been noted in NAFLD hospitalizations for ethnic minorities. Per current literature, the highest and lowest rates of NAFLD hospitalizations are for Hispanics and African Americans, respectively[13,16]. This has been attributed to dietary habits, lifestyle, and genetics as Hispanics have an allele of the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) that favors hepatic fat storage, while African Americans possess a different allele of the same gene associated with lower hepatic fat content[17,18]. Our study echoed similar findings as we noted a rising trend of NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD for Hispanics from 11% in 2009 to 15% in 2019 (P = 0.01) and a declining trend for Blacks from 10% in 2009 to 5% in 2019 (P = 0.01). These racial differences are important as we advocate for the need for aggressive public health measures for Hispanic populations to increase awareness about the burden of PUD in those who have NAFLD. Moreover, hospitalists and gastroenterologists who take care of NAFLD hospitalizations should have a high degree of suspicion of PUD in these patients.

In the United States, there has been a significant increase in inpatient mortality for NAFLD-cirrhosis by 32% between 2005-2015, despite a decrease in the inpatient mortality rates for patients with all other causes of liver cirrhosis[19]. However, there has been a significant decline in inpatient PUD mortality due to the increasing use of therapeutic endoscopic procedures for bleeding ulcers[20]. In our study, there was a rising trend of all-cause inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD (Table 2). From a race perspective, we noted an increasing trend of all-cause inpatient mortality for Blacks and Hispanics, while a decline was observed for Whites. The exact reasons for these findings are unknown, but they may, in part, be attributed to a higher comorbidity burden and the increasing mean age for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD, particularly for ethnic minorities i.e., Blacks and Hispanics (Table 1), leading to greater severity of disease and adverse outcomes. Interestingly, we noted lower all-cause inpatient mortality, mean LOS, and mean THC for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD compared to non-NAFLD PUD hospitalizations, despite a higher comorbidity burden. But there was no statistical difference in the proportion of patients with complications such as GI bleeding and perforation between the two groups. The exact reason for this protective effect of NAFLD is unclear and needs further investigation by multi-center prospective studies.

There has been a rapid decline in H. pylori infection rates in the western world secondary to higher standards of living and improved hygiene[21]. An analysis of outpatient endoscopy centers in the United States noted a significant fall in H. pylori infections from 11% in 2009 to 9% in 2018[22]. However, a recent cross-sectional study identified a positive relationship between H. pylori infection and NAFLD in females after adjusting for metabolic variables, gastrin factors, and liver enzymes[23]. This implies that rates of H. pylori infection may rise with an increasing prevalence of NAFLD. Our study contradicts these findings as we observed a declining trend of H. pylori infection in NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD (Table 1). Furthermore, we also noted a decline in the trends of utilization of upper endoscopy from 60% in 2009 to 19% in 2019. This may be due to increased adherence to guideline-directed management which advocates for non-endoscopic testing for uninvestigated dyspepsia without alarm features in individuals < 60 years of age[24]. However, due to an increasing trend of all-cause inpatient mortality in this subset population, it may be justified to perform upper endoscopy at an early stage to prevent adverse clinical outcomes. Interestingly, NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD had a higher proportion of patients that underwent upper endoscopy compared to non-NAFLD PUD hospitalizations. The exact reason for this is currently unknown and needs further investigation.

Our study has numerous strengths and some limitations. A key strength of this study is the study population, which is derived from one of the largest, publicly available, all-payer, multi-ethnic databases in the United States. An analysis over the 11-year study period allowed us to obtain meaningful information on the trends of hospitalization characteristics and outcomes for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD, adding to scarce literature. Moreover, through our unique and multifaceted comparative analysis, we were able to determine the influence of NAFLD on PUD. Furthermore, as the NIS database covers 97% of the United States population, the results of our study are applicable to almost all NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD, offering a national perspective. However, we do acknowledge the limitations associated with our study. This was a retrospective study design which is subject to all biases associated with retrospective studies. The NIS database does not contain information on the severity, time from hospitalization to discharge, hospital course, and other treatment aspects of the disease. Lastly, the NIS is an administrative database maintained through data collection organizations that use the ICD coding system to store inpatient data. Hence, the possibility of human coding errors cannot be excluded. However, despite these limitations, we believe that the large sample size and a comprehensive analysis technique help us better understand the trends, characteristics, and outcomes of NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD, and promote future research on the topic.

NAFLD is a public health concern and places a significant burden on the United States healthcare system. There is a significant knowledge gap on PUD in patients with NAFLD who are admitted to the hospital. We noted an increase the all-cause inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD in the United States between 2009-2019. There was a rising trend of NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD for Hispanics, reflecting the need for urgent public health measures to increase awareness in this subset population. Compared to non-NAFLD PUD hospitalizations, NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD had lower inpatient mortality, mean LOS, and mean THC despite a higher comorbidity burden. However, there was no statistical difference in GI bleeding and perforation between the two groups. Perforation of the GI tract, coagulopathy, alcohol abuse, malnutrition, and fluid and electrolyte disorders were identified to be independent predictors of all-cause inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD. Additional multi-center prospective studies are needed to further confirm these findings.

The association between peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and liver cirrhosis has been thoroughly investigated. However, there are knowledge gaps on PUD in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) hospitalizations. As the prevalence of NAFLD continues to rise across the globe and in the United States, it is vital to identify individuals with NAFLD at high risk of adverse clinical outcomes from PUD.

In current literature, there is a knowledge gap on PUD in NAFLD hospitalizations. Hence, this study was designed to help fill the knowledge gaps that currently exist in this subset population.

Our main objective was to identify national trends in hospitalization characteristics, clinical outcomes, and complications for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD. We also performed a comparative analysis between NAFLD and non-NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD to assess the influence of NAFLD on PUD.

The National Inpatient Sample was used from 2009-2019 to identify all adult (≥ 18 years) NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD in the United States. Furthermore, a control group of all adult PUD hospitalizations without NAFLD were identified for comparative analysis. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS 9.4. To test for the trend for proportions of binary variables, the Cochran-Armitage trend test was implemented. The trend for the averages of continuous variables in years was examined using linear regression. The Rao-Scott design-adjusted chi-square test examined the association between two categorical variables.

NAFLD-PUD hospitalizations increased from 3745 (2009) to 3805 (2019). Racial differences were noted as NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD increased for Whites and Hispanics, while a decline was observed for Blacks and Asians. There was an increase in all-cause inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD from 2% in 2009 to 5% in 2019 (P < 0.001). However, the rates of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and upper endoscopy decreased during the study period. Despite a high comorbidity burden, we observed lower inpatient mortality, mean length of hospital stay, and mean total healthcare cost (THC) for NAFLD-PUD hospitalizations vs the non-NAFLD-PUD cohort. Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract, coagulopathy, alcohol abuse, malnutrition, and fluid and electrolyte disorders were identified as independent predictors of inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD.

Between 2009-2019, inpatient mortality for NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD increased. However, there was a significant decline in H. pylori infections and esophagogastroduodenoscopy for NAFLD-PUD hospitalizations. After a comparative analysis, NAFLD-PUD hospitalizations had lower rates of mortality, mean length of hospital stay, and mean THC vs the non-NAFLD-PUD cohort despite a higher comorbidity burden.

This is one of the few national studies which investigates trends, clinical outcomes, and complications of NAFLD hospitalizations with PUD, using one of the largest, multi-ethnic databases in the United States. Future research should be directed toward identifying the underlying cause of racial disparities for this subset population.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: American College of Gastroenterology; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; American Gastroenterological Association.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shiryajev YN, Russia; Sitkin S, Russia; Thapar P, India S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Puri P, Sanyal AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Definitions, risk factors, and workup. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2012;1:99-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Duseja A, Chalasani N. Epidemiology and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Hepatol Int. 2013;7 Suppl 2:755-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5322] [Cited by in RCA: 7533] [Article Influence: 837.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, Perumpail RB, Harrison SA, Younossi ZM, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:547-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1211] [Cited by in RCA: 1382] [Article Influence: 138.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Lee SP, Sung IK, Kim JH, Lee SY, Park HS, Shim CS. Risk Factors for the Presence of Symptoms in Peptic Ulcer Disease. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:578-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lau JY, Sung J, Hill C, Henderson C, Howden CW, Metz DC. Systematic review of the epidemiology of complicated peptic ulcer disease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion. 2011;84:102-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sonnenberg A, Everhart JE. The prevalence of self-reported peptic ulcer in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:200-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xie X, Ren K, Zhou Z, Dang C, Zhang H. The global, regional and national burden of peptic ulcer disease from 1990 to 2019: a population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Siringo S, Burroughs AK, Bolondi L, Muia A, Di Febo G, Miglioli M, Cavalli G, Barbara L. Peptic ulcer and its course in cirrhosis: an endoscopic and clinical prospective study. J Hepatol. 1995;22:633-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nojkov B, Cappell MS. Distinctive aspects of peptic ulcer disease, Dieulafoy's lesion, and Mallory-Weiss syndrome in patients with advanced alcoholic liver disease or cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:446-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Introduction to the HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS). [cited 3 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_Introduction_2018.jsp. |

| 12. | Houchens R, Ross, D, Elixhauser A. Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Redesign Final Report (2014). [cited 3 December 2022]. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/methods.jsp. |

| 13. | Adejumo AC, Samuel GO, Adegbala OM, Adejumo KL, Ojelabi O, Akanbi O, Ogundipe OA, Pani L. Prevalence, trends, outcomes, and disparities in hospitalizations for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States. Ann Gastroenterol. 2019;32:504-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Doycheva I, Watt KD, Alkhouri N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adolescents and young adults: The next frontier in the epidemic. Hepatology. 2017;65:2100-2109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Feinstein LB, Holman RC, Yorita Christensen KL, Steiner CA, Swerdlow DL. Trends in hospitalizations for peptic ulcer disease, United States, 1998-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1410-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Arshad T, Paik JM, Biswas R, Alqahtani SA, Henry L, Younossi ZM. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Prevalence Trends Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States, 2007-2016. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:1676-1688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Saab S, Manne V, Nieto J, Schwimmer JB, Chalasani NP. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Latinos. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:5-12; quiz e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, Boerwinkle E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1461-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2701] [Cited by in RCA: 2596] [Article Influence: 152.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zou B, Yeo YH, Jeong D, Park H, Sheen E, Lee DH, Henry L, Garcia G, Ingelsson E, Cheung R, Nguyen MH. A Nationwide Study of Inpatient Admissions, Mortality, and Costs for Patients with Cirrhosis from 2005 to 2015 in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:1520-1528. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang YR, Richter JE, Dempsey DT. Trends and outcomes of hospitalizations for peptic ulcer disease in the United States, 1993 to 2006. Ann Surg. 2010;251:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Parsonnet J. The incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9 Suppl 2:45-51. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Sonnenberg A, Turner KO, Genta RM. Low Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori-Positive Peptic Ulcers in Private Outpatient Endoscopy Centers in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:244-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang J, Dong F, Su H, Zhu L, Shao S, Wu J, Liu H. H. pylori is related to NAFLD but only in female: A Cross-sectional Study. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:2303-2311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 1018] [Article Influence: 127.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |