Published online Dec 27, 2023. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v15.i12.1338

Peer-review started: September 13, 2023

First decision: October 16, 2023

Revised: October 21, 2023

Accepted: November 29, 2023

Article in press: November 29, 2023

Published online: December 27, 2023

Processing time: 102 Days and 15.4 Hours

Strongyloides sterocoralis is a parasitic infection caused by a roundworm that is transmitted through soil contaminated with larvae. It can infrequently cause hepatic abscesses in immunocompromised patients and is rarely reported to form hepatic lesions in immunocompetent hosts.

We present a case study of a 45-year-old female who presented with right upper quadrant abdominal pain and constitutional symptoms for several weeks. Cross-sectional imaging identified several malignant-appearing liver masses. Further investigation, including serological testing and histopathologic examination, revealed the presence of serum Strongyloides antibodies and hepatic granulomas with extensive necrosis. Following treatment with ivermectin for 2 wk, there was complete resolution of the liver lesions and associated symptoms.

This case highlights the importance of considering parasitic infections, such as Strongyloides, in the differential diagnosis of hepatic masses. Early recognition and appropriate treatment can lead to a favorable outcome and prevent unnecessary invasive procedures. Increased awareness among clinicians is crucial to ensure the timely diagnosis and management of such cases.

Core Tip: Hepatic pseudotumor is a clinical entity that can mimic malignant tumors of the liver. We report a rare case of hepatic pseudotumor caused by Strongyloides sterocoralis. Combined with a review of cases indexed in PubMed, we summarize the infectious causes of hepatic pseudotumor. Recognition of hepatic mass-forming parasitic infections may expedite prompt medical management.

- Citation: Gialanella JP, Steidl T, Korpela K, Grandhi MS, Langan RC, Alexander HR, Hudacko RM, Ecker BL. Hepatic pseudotumor associated with Strongyloides infection: A case report. World J Hepatol 2023; 15(12): 1338-1343

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v15/i12/1338.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v15.i12.1338

Inflammatory pseudotumors are mass-like lesions that have been described in various solid organs that mimic the appearance of a neoplasm[1]. Inflammatory pseudotumors represent a heterogeneous group of lesions of both infectious and inflammatory etiology, characterized histologically by the presence of fibroblasts or myofibroblasts and inflammatory cells and the lack of neoplastic cells. When occurring in the liver, hepatic pseudotumor often presents as a solitary, well-defined mass[1]. Due to its radiographic similarity to malignant liver tumors, potential misdiagnosis and unnecessary invasive interventions can occur. Given the variety of clinical presentations, including the absence of symptoms, the incidence of hepatic pseudotumor is not well characterized. It may account for 1% of all resected hepatic tumors[2], highlighting the importance of accurate diagnosis to prevent unneeded surgical resection. The pathogenesis of hepatic pseudotumor is poorly characterized but may be secondary to an exaggerated inflammatory response within the liver[1,3], as they often arise in the setting of infection, autoimmune disease, or recent trauma or surgery[1,3].

Strongyloidiasis is a parasitic infection known to infect the liver and biliary tree[3]. It is caused by the nematode Strongyloides sterocoralis, which is endemic in regions of West Africa, the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia – where the prevalence may be as high as 40%[4]. The parasitic larvae penetrate the skin and most commonly distribute to the gastrointestinal and pulmonary systems[5]. Less commonly, disseminated strongyloidiasis occurs when additional organs, including the liver, are involved[5,6]. Disseminated strongyloidiasis with hepatic infection has been primarily described in immunocompromised patients[7] but has rarely been observed in immunocompetent hosts[8].

Herein, we present a rare case of strongyloidiasis with hepatic involvement in an immunocompetent patient leading to the formation of a pseudotumor. By review of this case and the published literature, we summarize the incidence, diagnosis and treatment of Strongyloides pseudotumor.

A 45-year-old female was referred from the emergency room to hepatopancreatobiliary clinic for evaluation of liver lesions. She described several weeks of weight loss, decreased appetite, early satiety, fatigue, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain.

The patient was initially evaluated in the emergency room, where she reported a 15 lb weight loss secondary to abdominal pain and anorexia. The patient denied any change in bowel habits, sick contacts, or recent travel. The patient reported that her partner had immigrated from West Africa and that she had traveled there with him approximately 5 years earlier. She had also lived for several years in South Carolina, where Strongyloides may be endemic.

The patient had a history of hepatic steatosis, uterine fibroids, and morbid obesity. Upper and lower endoscopy had been performed 3 years earlier and were both found to be within normal limits.

The patient denied any family history of malignancy.

The vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 36.5°C; blood pressure, 136/76 mmHg; heart rate, 82 beats per min; and respiratory rate, 12 breaths per min. Abdominal exam was notable for tenderness in the right upper quadrant. There was no hepatosplenomegaly. There were no skin lesions present.

Laboratory examination was notable for marked eosinophilia [0.9 × 103/mL (range 0.0-0.40)] and an elevated sedimentation rate (Westergren; 94 mm/h). Tumor markers were normal (alpha-fetoprotein < 1.8 ng/mL; carbohydrate antigen 19-9 16 U/mL; carcinoembryonic antigen 2.1 ng/mL). Liver function tests were normal, and hepatitis serologies were consistent with previous hepatitis B immunization. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody (Ab)/p24 antigen screen, rapid plasma reagin, coccidioides Ab panel, cryptococcus antigen, and quantiFERON-TB Gold Plus were negative. Autoimmune markers were negative (anti-myeloperoxidase Ab < 0.2 units; anti-proteinase 3 Ab < 0.2 units; cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic Ab (ANCA) < 1:2 titer; perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) < 1:20 titer; atypical p-ANCA < 1:20 titer; angiotensin converting enzyme, serum 42 U/L; anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide Ab, immunoglobulin G (IgG)/IgA 2 U; rheumatoid factor < 10.0 IU/mL; antinuclear Ab direct-negative).

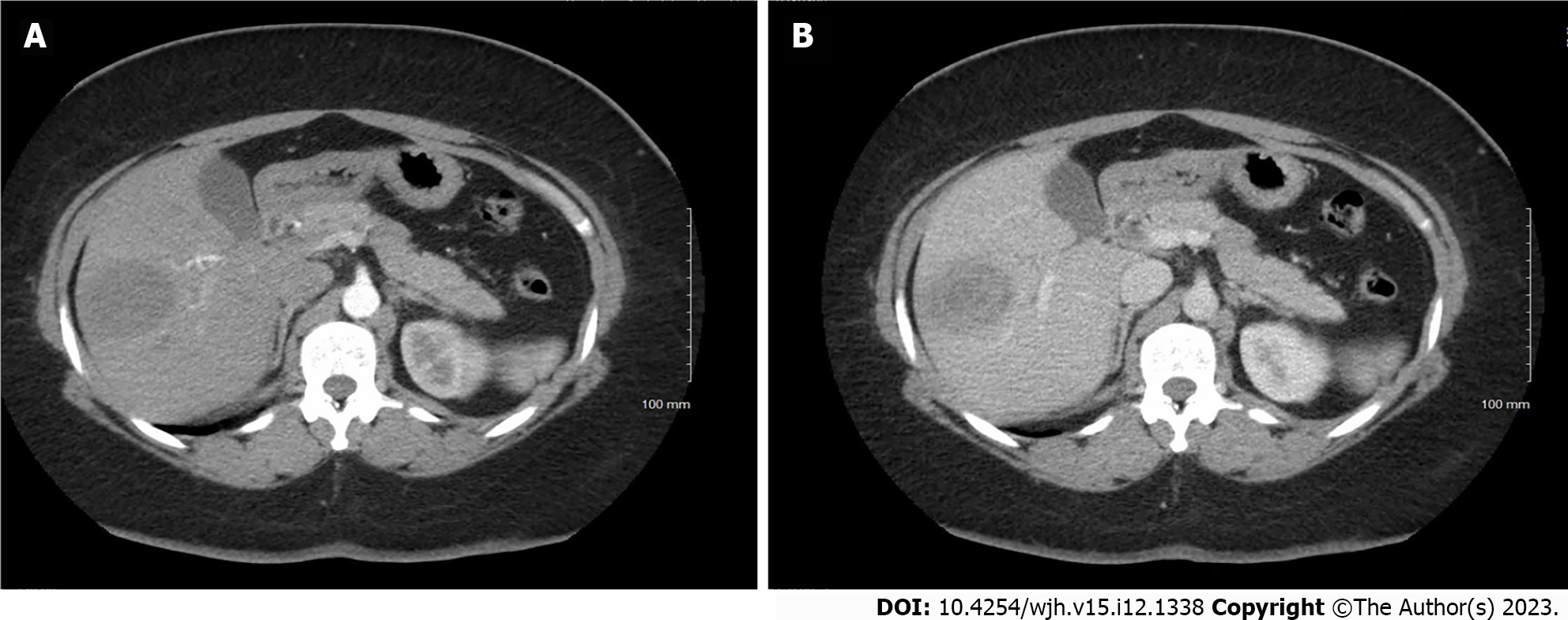

An abdominal ultrasound performed in the emergency room noted a focal hypoechoic area within the right hepatic lobe centrally measuring 2.5 cm × 1.6 cm × 1.3 cm. Subsequently, a gadolium-enhanced magnetic resonance image demonstrated a non-cirrhotic liver with a peripherally T2 hyperintense and centrally T2 hypointense 3.7 cm × 3.2 cm × 3.7 cm lesion (Figure 1). Signal characteristics raised suspicion for a malignancy, but the rapid interval growth (from ultrasound-estimated size) suggested possible infection. A computerized tomography scan through the abdomen (Figure 2) demonstrated a low-density mass within the right hepatic lobe measuring up to 4.5 cm × 4.9 cm in the largest dimensions. There was peripheral enhancement with centripetal filling atypical for a hemangioma.

The final diagnosis was hepatic pseudotumor caused by S. sterocoralis.

The treatment provided to the patient was ivermectin 24 mg by mouth daily for 2 wk.

Liver lesions and systemic symptoms both resolved shortly after treatment (Figure 3).

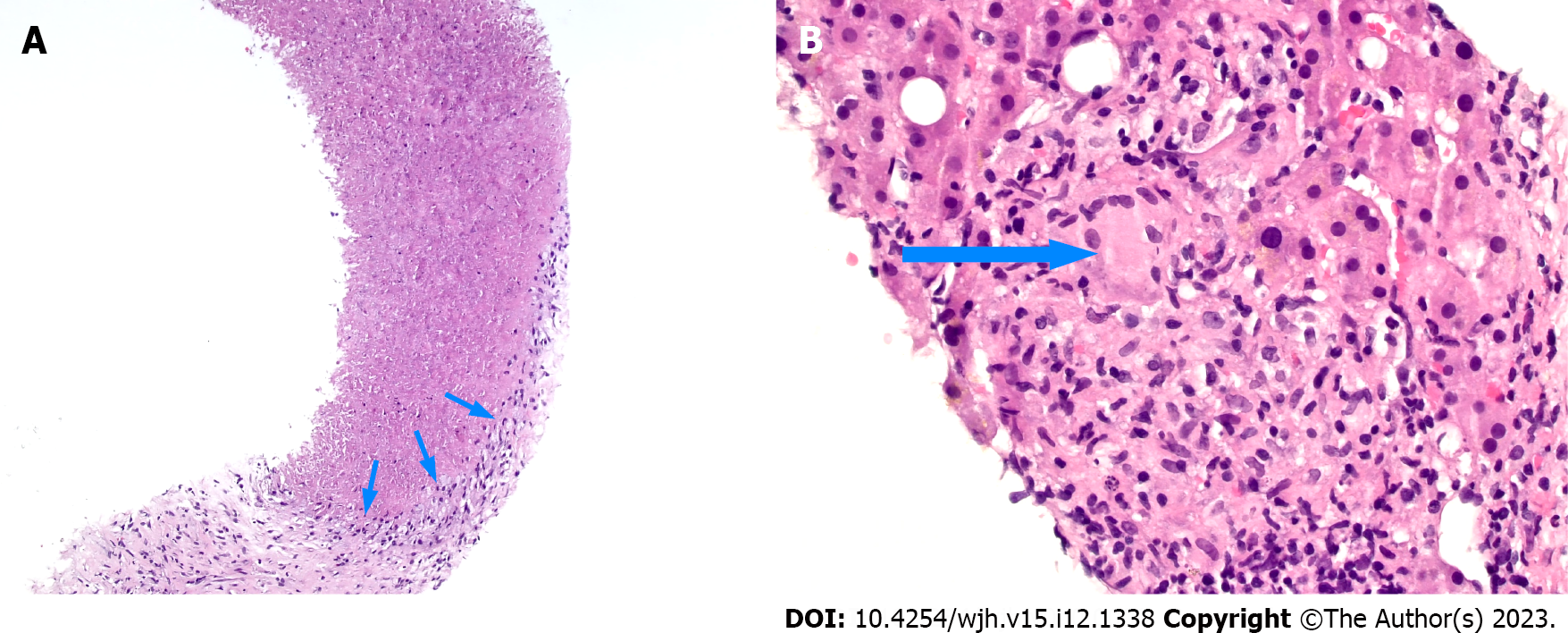

Inflammatory pseudotumor can be idiopathic, infectious, or inflammatory in nature; yet, there are several clinical features of hepatic pseudotumors that suggest an infectious etiology. We present a case of infectious hepatic pseudotumor caused by S. sterocoralis. The systemic symptoms of anorexia and malaise, coupled with marked eosinophilia, positive Strongyloides serum antibodies, and the presence of granulomas with necrosis on pathologic evaluation, along with clinical improvement with antihelminth therapy, support this rare diagnosis and highlight the importance of considering such infectious etiologies in the management of hepatic masses.

To date, the medical literature includes only two published reports of Strongyloides hepatic pseudotumor[7,8], which were diagnosed in patients with immunocompromise secondary to HIV or steroid use, respectively. While expected to be rare in the United States, the true prevalence of Strongyloides is not known. In the southeastern United States, particularly Appalachia, Strongyloides seroprevalence may approach 2%, and may be as high as 10% in South Carolina[9] - where the patient had previously resided. More commonly, Strongyloides is endemic to the soil of tropical and subtropical countries, where the nematode larvae migrate through the skin into human hosts and mature to the adult stage[10-12]. Strongyloides can perpetually reinfect a patient as the rhabditiform larvae develop into infective filariform larvae and pass into the feces. Strongyloidiasis may remain asymptomatic for many years in immunocompetent patients[10], whereas hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated strongyloidiasis are more common among immunosuppressed hosts[11,12]. In healthy individuals, nematodes have been shown to stay in the body for over 50 years without causing symptoms. It is plausible that this particular case represents a delayed presentation of a clinical exposure years prior with a long period of asymptomatic infection.

Other etiologies of infectious hepatic pseudotumor include Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Brucella, Bartonella, syphilis, Candida, and Actinomyces. Tuberculosis can cause a localized hepatic lesion, either as a tuberculoma with confluent granulomas and few organisms in immune competent individuals, or a tuberculous abscess, which is often suppurative and contains numerous organisms in immunocompromised hosts[13]. A Brucelloma is typically seen in the context of reactivation of remote infection, usually originating from animals or animal products from high-risk regions, typically surrounding the Mediterranean[14].The clinical presentation of hepatic Brucelloma overlaps with many of the symptoms of brucellosis, typically chronic, undulating fevers, malaise, and anorexia. There may be right upper quadrant pain. Diagnosis of hepatic Brucelloma is validated by serological positivity and positive cultures on blood or tissue samples. Hepatic cat scratch disease, caused by B. henselae, may present with abdominal lymphadenopathy and skin papules. It can form irregular stellate hepatic abscesses, histologically characterized by palisading histiocytes, lymphocytes, and a rim of fibrosis[13]. Hepatic syphilis can occur in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients[15-17]. Immunohistochemical stain for Treponema pallidum highlights the organisms in these pseudotumors; additionally, there is often periductal edema and neutrophilic pericholangitis in portal tracts outside the mass lesion. Hepatic candidiasis is most often observed in immunocompromised patients[18] and on histologic examination, may show granulomas or abscesses containing pseudohyphae and/or yeast forms[13]. Lastly, Actinomycosis can cause hepatic fibrotic masses containing characteristic sulfur granules and colonies of filamentous organisms[19,20]. In summary, patient history and exposures are important considerations when considering these infectious causes of hepatic pseudotumor in order to guide further testing for diagnostic confirmation.

While most hepatic pseudotumors are presumed to be a response to infection, the causative agent is not always identified. Additionally, there are several malignancies and inflammatory diseases that must be considered. Beyond primary (i.e. cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma) and metastatic liver tumors, there are several neoplasms that particularly resemble hepatic pseudotumor. These include inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT), follicular dendritic cell tumor, and less commonly, Hodgkin lymphoma. When in question, further testing on tissue samples can help distinguish these diagnoses (IMT with ALK or ROS1 expression; follicular dendritic cell tumor with in situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus; Hodgkin lymphoma with immunohistochemical analysis). Non-infectious inflammatory hepatic pseudotumor can be observed in IgG4-related disease. While most commonly manifested as a form of sclerosing cholangitis and thus a mimic of cholangiocarcinoma, IgG4-related hepatic pseudotumors can form adjacent to involved ducts[21,22]. Histologically, IgG4-related hepatic pseudotumors are characterized by numerous IgG4-positive plasma cells on immunohistochemical staining.

Several limitations warrant emphasis. For this case, the Strongyloides IgG Ab titer was not available, and was only reported by the laboratory as a binary (i.e. positive/negative); thus, we cannot comment on the degree of elevation that may be observed with this subset of hepatic disease. Second, for completeness of the presentation of the history and evaluation of this case, we hoped to include a representative image of the Strongyloides larvae from the stool examination, but this could not be provided by the commercial laboratory involved.

Hepatic masses are a heterogenous pathology of malignant, inflammatory and infectious etiologies. This rare case study of hepatic pseudotumor caused by strongyloidiasis infection highlights the broad diversity of diagnoses that need be considered, even in geographic regions and patient cohorts not typical of opportunistic infections. Moreover, the clinical presentation – namely, eosinophilia, positive serum antibodies and necrotic granulomas – review the typical features of Strongyloides-induced pseudotumor. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying biology of hepatic pseudotumor formation and improve diagnostic accuracy. Recognizing the pivotal role of infections in the differential diagnosis of hepatic pseudotumor is paramount for safeguarding patients from undergoing unnecessary invasive procedures. This approach not only facilitates accurate diagnosis and timely initiation of appropriate treatments but also prevents unwarranted interventions, underscoring the significance of a comprehensive consideration of infections in the diagnostic algorithm of hepatic pseudotumor cases.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Leowattana W, Thailand S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Lin C

| 1. | Ntinas A, Kardassis D, Miliaras D, Tsinoglou K, Dimitriades A, Vrochides D. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Torbenson M, Yasir S, Anders R, Guy CD, Lee HE, Venkatesh SK, Wu TT, Chen ZE. Regenerative hepatic pseudotumor: a new pseudotumor of the liver. Hum Pathol. 2020;99:43-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pascariu AD, Neagu AI, Neagu AV, Băjenaru A, Bețianu CI. Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular dendritic cell tumor: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15:410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Mahmoud AA. Strongyloidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:949-52; quiz 953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Centers of Disease Control and Prevention: Resources for Health Professionals. Oct 5, 2023. [cited 3 August 2023]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/strongyloides/health_professionals/index.html. |

| 6. | Rodriguez-Hernandez MJ, Ruiz-Perez-Pipaon M, Cañas E, Bernal C, Gavilan F. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection transmitted by liver allograft in a transplant recipient. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2637-2640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gulbas Z, Kebapci M, Pasaoglu O, Vardareli E. Successful ivermectin treatment of hepatic strongyloidiasis presenting with severe eosinophilia. South Med J. 2004;97:907-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strongyloidiasis Infection FAQs. Jul 3, 2023. [cited 29 July 2023]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/strongyloides/gen_info/faqs.html. |

| 9. | Cleveland Clinic. Strongyloidiasis. [cited 29 July 2023]. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/14074-strongyloidiasis. |

| 10. | Carpio ALM, Meseeha M. Strongyloides stercoralis Infection. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2023. |

| 11. | Mora Carpio AL, Meseeha M. Strongyloides stercoralis Infection. 2023 Feb 7. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Schär F, Trostdorf U, Giardina F, Khieu V, Muth S, Marti H, Vounatsou P, Odermatt P. Strongyloides stercoralis: Global Distribution and Risk Factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 485] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Masia R, Misdraji J. Liver and Bile Duct Infections. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease. 2018;272-322. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barutta L, Ferrigno D, Melchio R, Borretta V, Bracco C, Brignone C, Giraudo A, Serraino C, Baralis E, Grosso M, Fenoglio LM. Hepatic brucelloma. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:987-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Malvar G, Cardona D, Pezhouh MK, Adeyi OA, Chatterjee D, Deisch JK, Lamps LW, Misdraji J, Stueck AE, Voltaggio L, Gonzalez RS. Hepatic Secondary Syphilis Can Cause a Variety of Histologic Patterns and May Be Negative for Treponeme Immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2022;46:567-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | DeRoche TC, Huber AR. The Great Imitator: Syphilis Presenting as an Inflammatory Pseudotumor of Liver. Int J Surg Pathol. 2018;26:528-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hagen CE, Kamionek M, McKinsey DS, Misdraji J. Syphilis presenting as inflammatory tumors of the liver in HIV-positive homosexual men. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1636-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Moazzam Z, Yousaf A, Iqbal Z, Tayyab A, Hayat MH. Hepatic Candidiasis in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Diagnostic Challenge. Cureus. 2021;13:e13935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kaplan K, Sarıcı KB, Usta S, Özdemir F, Işık B, Yılmaz S. Primary Hepatic Actinomycosis Mimicking Neuroendocrine Tumor. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2023;54:294-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kothadia JP, Samant H, Olivera-Martinez M. Actinomycotic Hepatic Abscess Mimicking Liver Tumor. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:e86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zen Y, Harada K, Sasaki M, Sato Y, Tsuneyama K, Haratake J, Kurumaya H, Katayanagi K, Masuda S, Niwa H, Morimoto H, Miwa A, Uchiyama A, Portmann BC, Nakanuma Y. IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis with and without hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor, and sclerosing pancreatitis-associated sclerosing cholangitis: do they belong to a spectrum of sclerosing pancreatitis? Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1193-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Oseini AM, Chaiteerakij R, Shire AM, Ghazale A, Kaiya J, Moser CD, Aderca I, Mettler TA, Therneau TM, Zhang L, Takahashi N, Chari ST, Roberts LR. Utility of serum immunoglobulin G4 in distinguishing immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54:940-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |