Published online Dec 27, 2023. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v15.i12.1294

Peer-review started: September 6, 2023

First decision: October 25, 2023

Revised: November 7, 2023

Accepted: November 24, 2023

Article in press: November 24, 2023

Published online: December 27, 2023

Processing time: 109 Days and 18.3 Hours

Liver cirrhosis (LC) is a prevalent and severe disease in China. The burden of LC is changing with widespread vaccination of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and antiviral therapy. However, the recent transition in etiologies and clinical features of LC cases requiring hospitalization is unclear.

To identify the transition in etiologies and clinical characteristics of hospitalized LC patients in Southern China.

In this retrospective, cross-sectional study we included LC inpatients admitted between January 2001 and December 2020. Medical data indicating etiological diagnosis and LC complications, and demographic, laboratory, and imaging data were collected from our hospital-based dataset. The etiologies of LC were mainly determined according to the discharge diagnosis, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), portal vein thrombosis, hepatorenal syndrome, and acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) were considered LC-related complications in our study. Changing trends in the etiologies and clinical characteristics were investigated using logistic regression, and temporal trends in proportions of separated years were investigated using the Cochran-Armitage test. In-hospital prognosis and risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality were also investigated.

A total of 33143 patients were included in the study [mean (SD) age, 51.7 (11.9) years], and 82.2% were males. The mean age of the study population increased from 51.0 years in 2001-2010 to 52.0 years in 2011-2020 (P < 0.001), and the proportion of female patients increased from 16.7% in 2001-2010 to 18.2% in 2011-2020 (P = 0.003). LC patients in the decompensated stage at diagnosis decreased from 68.1% in 2001-2010 to 64.6% in 2011-2020 (P < 0.001), and the median score of model for end-stage liver disease also decreased from 14.0 to 11.0 (P < 0.001). HBV remained the major etiology of LC (75.0%) and the dominant cause of viral hepatitis-LC (94.5%) during the study period. However, the proportion of HBV-LC decreased from 82.4% in 2001-2005 to 74.2% in 2016-2020, and the proportion of viral hepatitis-LC decreased from 85.2% in 2001-2005 to 78.1% in 2016-2020 (both P for trend < 0.001). Meanwhile, the proportions of LC caused by alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis and mixed etiology increased by 2.5%, 0.8% and 4.5%, respectively (all P for trend < 0.001). In-hospital mortality was stable at 1.0% in 2011-2020, whereas HCC and ACLF manifested the highest increases in prevalence among all LC complications (35.8% to 41.0% and 5.7% to 12.4%, respectively) and were associated with 6-fold and 4-fold increased risks of mortality (odds ratios: 6.03 and 4.22, respectively).

LC inpatients have experienced changes in age distribution and etiologies of cirrhosis over the last 20 years in Southern China. HCC and ACLF are associated with the highest risk of in-hospital mortality among LC complications.

Core Tip: The etiologies and clinical characteristics of liver cirrhosis (LC) in hospitalized patients changed during the 2001-2020 period in Southern China. The mean age and female proportion have increased but the disease severity at LC diagnosis has alleviated over time. The proportion of hepatitis B virus-LC has decreased, while proportions of LC caused by alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis and mixed etiology have increased gradually. Among all complications of LC, hepatocellular carcinoma and acute-on-chronic liver failure manifest the highest increase in prevalence and are associated with the highest risk of in-hospital mortality.

- Citation: Wang X, Luo JN, Wu XY, Zhang QX, Wu B. Study of liver cirrhosis over twenty consecutive years in adults in Southern China. World J Hepatol 2023; 15(12): 1294-1306

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v15/i12/1294.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v15.i12.1294

Liver cirrhosis (LC) is the end stage of progressive liver fibrosis and causes more than 1.3 million deaths worldwide annually, whereas the underlying etiologies, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and alcohol intake, negatively impact 1.5 billion people[1-3]. China accounts for a large proportion of the regional burden of LC, with an estimated 7 million cirrhotic patients, and the annual incident cases are approximately 220000[4,5].

Because of widespread HBV vaccination and the development of potent antiviral treatment for HBV and HCV, the LC mortality rate has greatly decreased from 20.0 per 100000 person-years in the 1980s to 15.8 per 100000 person-years in the 2010s globally[2]. However, there have been 10%-20% increases in LC incidence from 2000 to 2015 in North America, Europe, and East Asia[4,5]. Meanwhile, hospital-based studies from North America and Japan found that the proportion of viral hepatitis LC decreased, whereas non-viral etiologies, including LC caused by alcoholic liver disease (ALD), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), increased over the years[6,7]. Previous studies in China also reported similar changing trends[8,9], but the recent transition in etiologies of LC patients is unclear. Continuous work investigating the trend of newly diagnosed LC is urgent and critical to facilitate clinical practice and evidence-based policy-making. Furthermore, most previous studies defined ‘cirrhosis’ as LC and chronic liver diseases together, whereas data addressing clinically diagnosed LC cases, especially cases requiring hospitalization with detailed clinical features, were scant[1,2]. In this context, we conducted this study to investigate changing trends in etiologies, clinical features and in-hospital prognosis of LC inpatients. Moreover, we compared the recent data to our previous study to explore the etiological evolution of LC over 20 years[8].

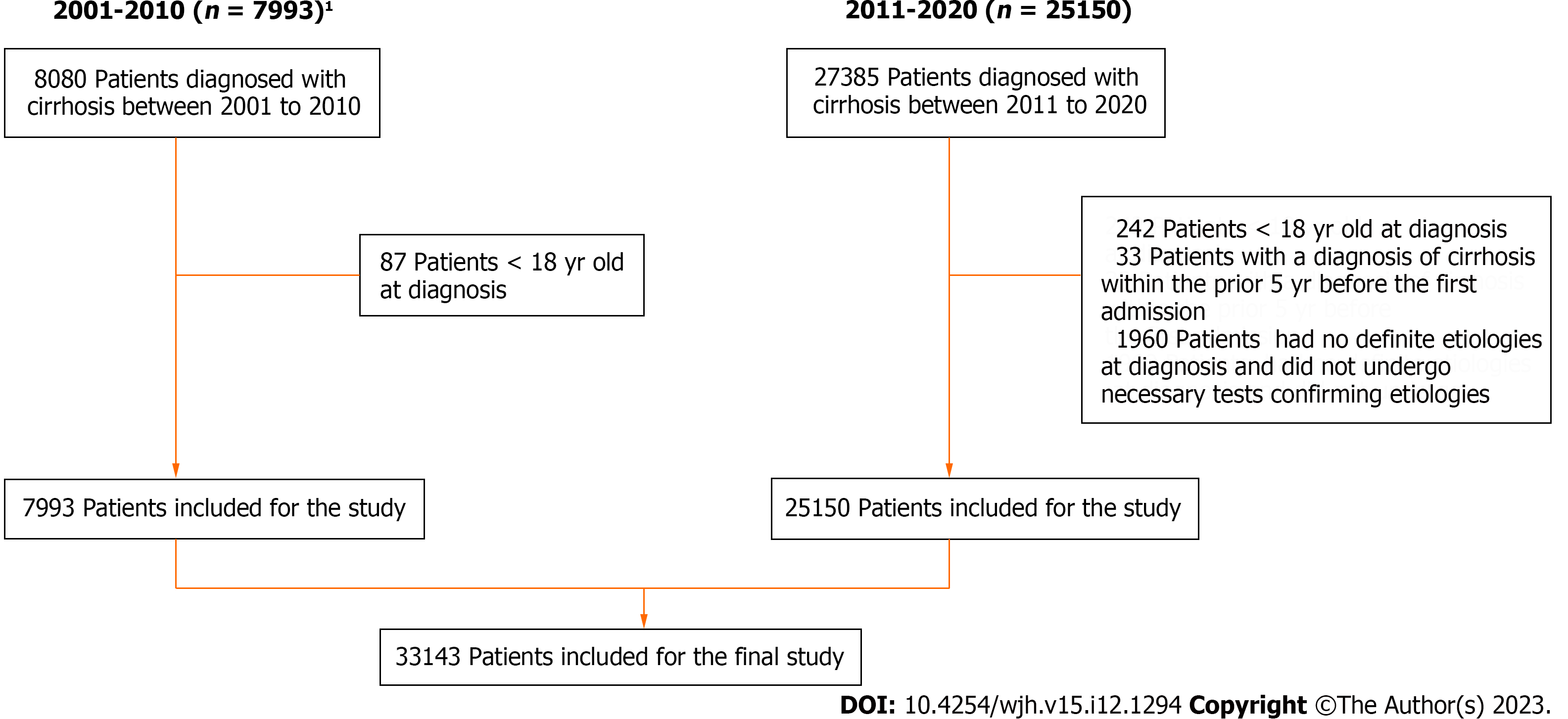

We performed this retrospective cross-sectional study based on data extracted from the electronic dataset of medical records of our hospital, which is a university-affiliated, tertiary medical center and specialized liver center in Southern China. The diagnosis of LC was based on the discharging diagnosis code established according to the International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision. Hospitalization records with a diagnostic code of cirrhosis (K70, K71, K74) or discharge diagnosis of LC admitted from Jan 2011 to Dec 2020 were extracted. In clinical practice, LC diagnosis is established according to clinical manifestations of impaired liver function and/or portal hypertension in combination with typical biochemical and radiological findings or liver biopsies[7,10]. Patients were included if they were aged 18 years or older at the time of diagnosis. To ensure that these were incident cases, we only collected the first admission record during the study period, and patients with a diagnosis of cirrhosis within the prior 5 years before the first admission were excluded. Moreover, we excluded patients who had no definite etiologies at diagnosis and did not undergo necessary laboratory tests to confirm etiologies. The patient selection flowchart is shown in Figure 1. This study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013. Informed consent was waived because we used deidentified retrospective data. This article follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines[11].

The etiologies of LC were mainly determined according to the discharge diagnosis in the medical record. If the etiology was not confirmed in the discharge diagnosis, further screening of the collected data was performed to confirm the etiology according to the criteria elaborated in our previous work[8]. Generally, viral hepatitis was diagnosed according to universally accepted serological criteria, including positivity of HBs antigen for HBV infection and positivity of HCV antibodies or HCV RNA for HCV infection. The diagnosis of ALD was based on established criteria[8,12]. Considering other non-viral etiologies, several classifications require attention as follows: (1) LC caused by primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis or biliary cirrhosis secondary to biliary tract obstruction was classified as cholestatic LC; (2) LC caused by Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis, MASLD, glycogen storage disease, or amyloidosis was classified as genetic or metabolic LC; and (3) LC caused by more than one etiology was classified as LC of mixed etiology, except for HBV-HCV overlap LC, which was classified as HBV + HCV LC[7,8].

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), variceal bleeding, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), portal vein thrombosis (PVT), hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), and acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) were considered LC-related complications in our study. UGIB and variceal bleeding were diagnosed according to discharge diagnosis, or symptoms of hematemesis or melena, in combination with esophageal varices/gastric varices in the diagnosis or procedure code for band ligation, injective sclerotherapy or tissue glue injection[10]. Ascites was diagnosed according to discharge diagnosis, procedure code for paracentesis, or corresponding imaging findings. HE, HCC and PVT were diagnosed according to discharge diagnosis or corresponding imaging findings. ACLF was diagnosed according to discharge diagnosis, or acute aggravation of bilirubinemia and coagulation dysfunction on the basis of chronic liver disease per Chinese guideline[13]. SBP and HRS were diagnosed based on discharge diagnosis[6]. Liver decompensation was defined as the presence of any one of ascites, variceal bleeding, HE, or jaundice[14].

Demographic, clinical and laboratory data at the index admission were extracted along with imaging reports of abdominal ultrasound, computerized tomography or magnetic resonance. Moreover, variables associated with etiologies and complications were also collected. Outcome variables, including deaths and liver transplantation (LT) during hospitalization and intensive care unit (ICU) admission, were only collected during the 2011-2020 period. Data from adult patients in our previous study[8] were collected to delineate the evolution of etiologies, clinical features, and complications of LC from 2001 to 2020 (Figure 1).

Categorical variables were described using counts and percentages, and comparisons were performed with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. Quantitative variables were described using means ± SD or medians and interquartile range (IQR), and Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test were performed as applicable. The trend of etiological proportion every 5 years was investigated using ordered logistic regression, and temporal trends in proportions of separated years were assessed using the Cochran-Armitage test. Moving average analysis and univariable linear regressions were performed to investigate trends in the mean ages of the study population, and the coefficient of determination (R square) was used to measure the strength of the correlation between mean ages and diagnosis years. Logistic regressions were used to explore risk factors for in-hospital mortality. Two-tailed P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using R statistics version 4.2.0 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

A total of 33143 patients were included in the study from Jan 2001 to Dec 2020 (7993 patients in 2001-2010 and 25150 patients in 2011-2020). Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age at diagnosis was 51.7 years, and 82.2% of patients were men. The median (IQR) model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was 12 (8.0, 18.0), and 31.7% of patients had MELD scores of 15 or above. As many as 65.5% of patients were in the decompensated stage, and the most prevalent complications were ascites (50.3%), HCC (36.7%) and UGIB (14.3%). During the 2011-2020 period, 6.8% of patients were referred from the emergency room, and 54.0% of patients were reimbursed by medical insurance for hospitalization (Supplementary Table 1).

| Characteristic | Total population, n = 33143 | 2001-2010, n = 7993 | 2011-2020, n = 25150 | P value |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 51.7 (11.9) | 51.0 (12.3) | 52.0 (11.8) | < 0.001 |

| Gender (male, %) | 27237 (82.2) | 6658 (83.3) | 20579 (81.8) | 0.003 |

| Laboratory test (mean ± SD) | ||||

| Albumin (g/L) | 34.1 (6.3) | 33.4 (6.4) | 34.2 (6.2) | < 0.001 |

| Bilirubin (umol/L) | 87.7 (139.4) | 98.3 (148.9) | 85.4 (137.1) | < 0.001 |

| Prothrombin INR | 1.45 (0.65) | 1.53 (0.65) | 1.44 (0.65) | < 0.001 |

| MELD score (Median, IQR) | 12.0 (8.0,18.0) | 14.0 (10.0, 19.0) | 11.0 (8.0,18.0) | < 0.001 |

| Decompensation1 (n,%) | 21701 (65.5) | 5443 (68.1) | 16258 (64.6) | < 0.001 |

| Complications | ||||

| UGIB | 4729 (14.3) | 998 (12.5) | 3731 (14.8) | < 0.001 |

| Ascites | 16656 (50.3) | 4444 (55.6) | 12212 (48.6) | < 0.001 |

| HE | 1901 (5.7) | 535 (6.7) | 1366 (5.4) | 0.007 |

| HCC | 12159 (36.7) | 2392 (29.9) | 9767 (38.8) | < 0.001 |

| PVT | 2449 (7.4) | 403 (5.0) | 2046 (8.1) | < 0.001 |

| HRS | 713 (2.2) | 291 (3.6) | 422 (1.7) | < 0.001 |

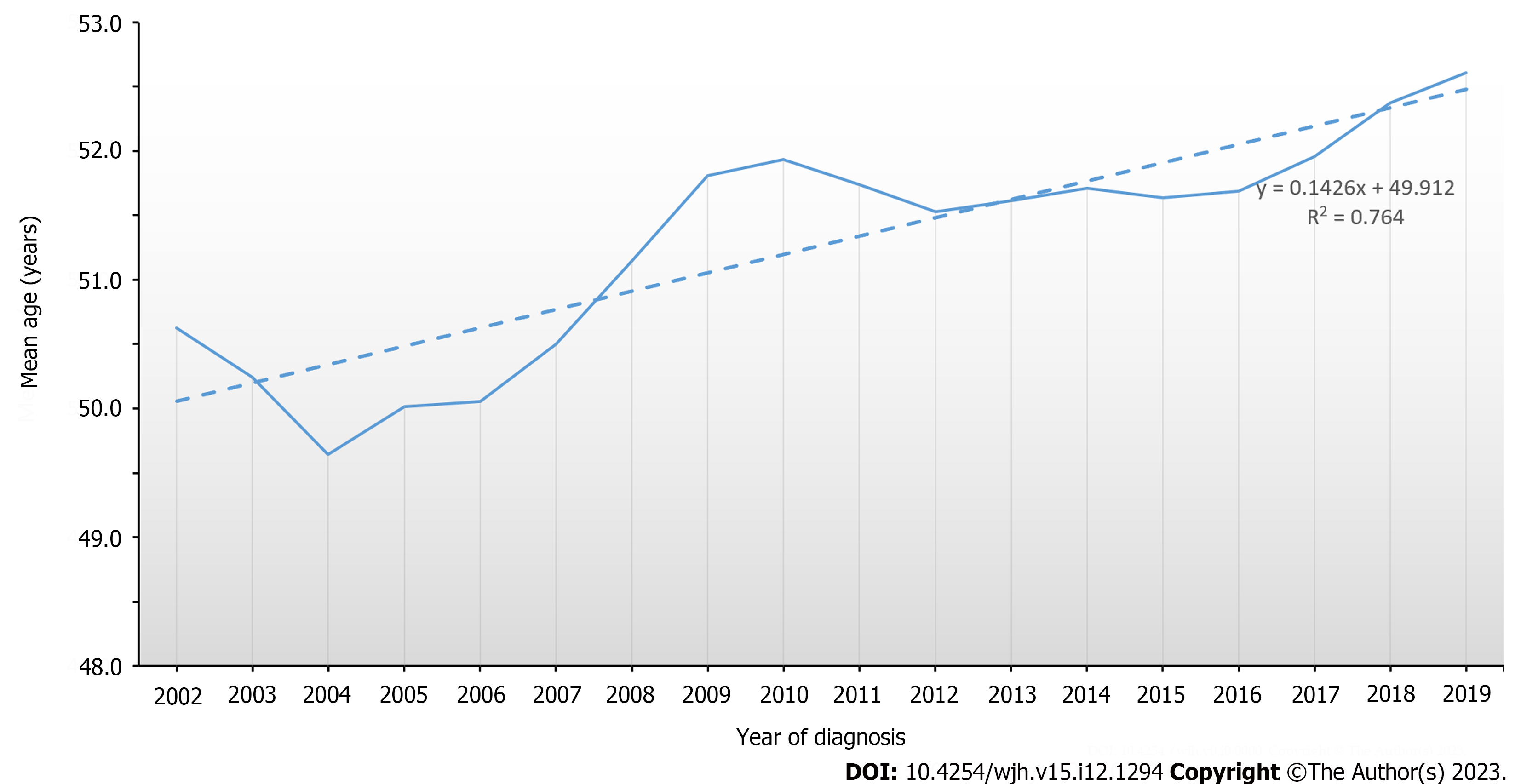

The mean age of LC inpatients increased from 51.0 years in 2001-2010 to 52.0 years in 2011-2020 (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Three-year moving average analysis showed that the increasing trend was continuous, and the value increased linearly from 50.6 years in 2001-2003 to 52.6 years in 2018-2020 (R2 = 0.764, Figure 2). The proportion of female patients increased from 16.7% in 2001-2010 to 18.2% in 2011-2020 (P = 0.003). During the 2001-2020 period, the proportion of patients in the decompensated stage decreased from 68.1% to 64.6% (P < 0.001), and the median MELD score also decreased from 14.0 to 11.0 (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Meanwhile, HCC and UGIB increased by nearly 10% and over 2%, respectively (both P < 0.001). During the 2011-2020 period, the proportion of patients with ACLF and patients referred from the emergency department increased dramatically from 5.7% to 12.4% and 5.1% to 8.1%, respectively (both P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 1).

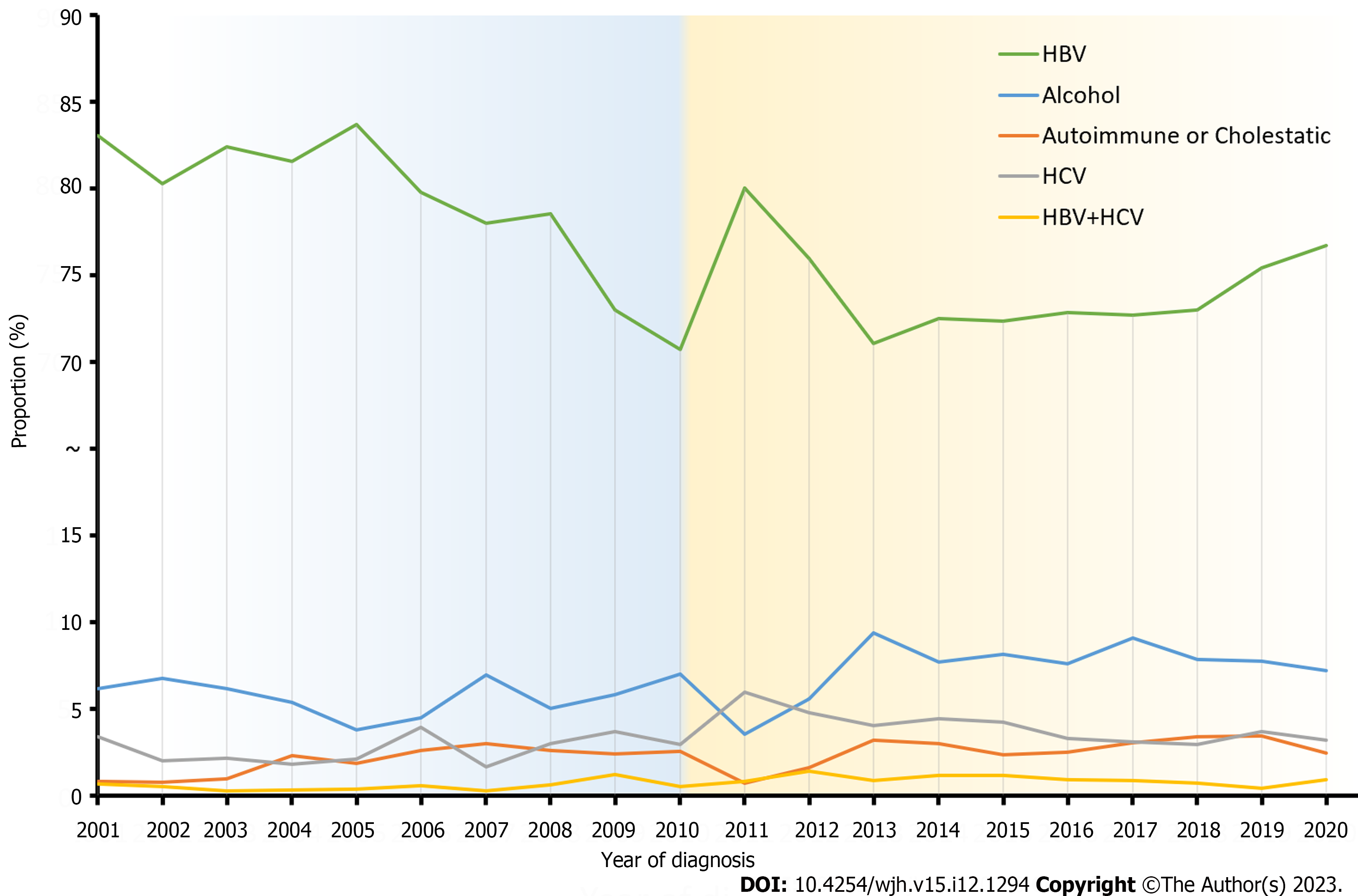

The top three causes of LC were viral hepatitis (79.3%), ALD (7.1%) and mixed etiology (7.6%) in the entire population, and this pattern of constitution did not change over the 20 years (Table 2). HBV cirrhosis accounted for 75.0% of the entire population, and 94.5% of the patients had viral hepatitis. HCV and HBV + HCV etiologies accounted for 3.6% and 0.8%, respectively. The etiology distribution is presented in Table 2.

| Etiology | 2001-2005, n = 2870 | 2006-2010, n = 5123 | 2011-2015, n = 10538 | 2016-2020, n = 14612 | P value1 | P value2 |

| Viral hepatitis | 2444 (85.2) | 4046 (79.0) | 8385 (79.6) | 11418 (78.1) | < 0.001 | 0.780 |

| HBV | 2366 (82.4) | 3852 (75.2) | 7788 (73.9) | 10835 (74.2) | < 0.001 | 0.747 |

| HCV | 66 (2.3) | 159 (3.1) | 484 (4.6) | 474 (3.2) | 0.951 | 0.912 |

| HBV + HCV | 12 (0.4) | 35 (0.7) | 113 (1.1) | 109 (0.7) | 0.685 | 0.932 |

| Alcohol | 155 (5.4) | 304 (5.9) | 753 (7.1) | 1155 (7.9) | < 0.001 | 0.869 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 12 (0.4) | 41 (0.8) | 87 (0.8) | 170 (1.2) | < 0.001 | 0.875 |

| Cholestatic | 29 (1.0) | 92 (1.8) | 154 (1.5) | 266 (1.8) | 0.005 | 0.925 |

| Genetic or Metabolic | 21 (0.7) | 62 (1.2) | 105 (1.0) | 191 (1.3) | 0.019 | 0.923 |

| Mixed etiology | 102 (3.6) | 374 (7.3) | 864 (8.2) | 1188 (8.1) | < 0.001 | 0.771 |

| Cryptogenic | 74 (2.6) | 153 (3.0) | 70 (0.7) | 36 (0.2) | < 0.001 | 0.746 |

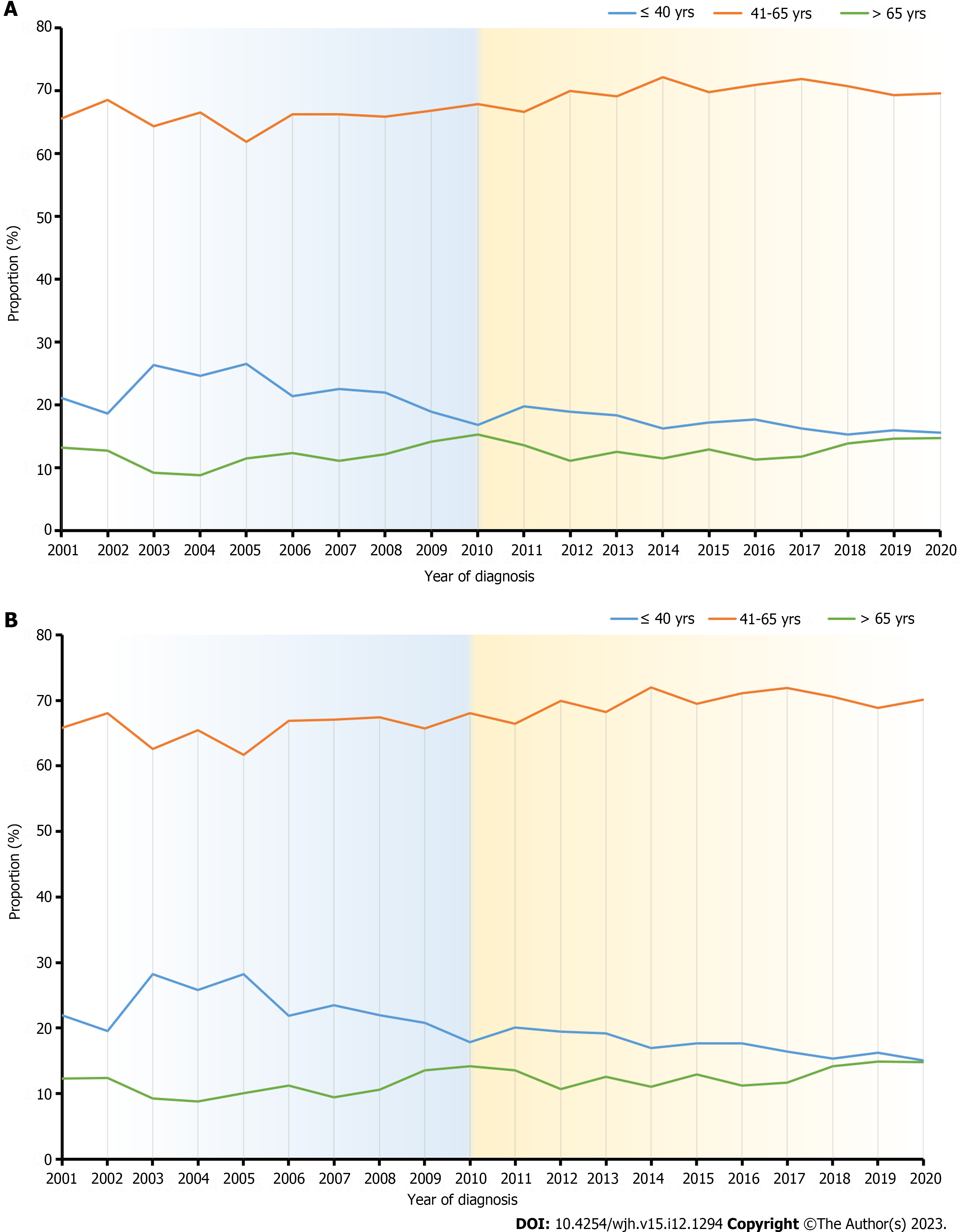

To determine the transition in etiology over the 20-year study period, we divided the study population into four groups, which were defined as 2001 to 2005, 2006 to 2010, 2011 to 2015 and 2016 to 2020. As shown in Table 2, proportions of the top three etiologies changed dramatically over the years. Viral hepatitis decreased from 85.2% to 78.1%, and ALD and mixed etiology increased by 2.5% and 4.5%, respectively (all P for trend < 0.001). Meanwhile, AIH and cholestatic etiology steadily increased from 0.4% to 1.2% (P for trend < 0.001) and 1.0% to 1.8% (P for trend = 0.018), respectively. As the major cause of viral hepatitis LC, HBV cirrhosis also decreased from 82.4% to 74.2% during the period (P for trend < 0.001). When comparing the proportions of separated years, the Cochran-Armitage test for P trend (CAP) found no statistical significance (CAP values > 0.05) (Table 2). Temporal trends of the major etiologies are illustrated in Figure 3. When comparing the proportion of different age groups (≤ 40 years as the young-age group, 41-65 years as the middle-age group, and > 65 years as the old-age group) in different etiologies, the proportion of young-aged patients gradually decreased from 21.2% in 2001 to 15.7% in 2020, whereas the proportion of middle-aged patients and old-aged patients increased from 65.6% to 69.6% and 13.3% to 14.7%, respectively (Figure 4A). Similar patterns of trends were also observed when restricting the population to HBV LC (Figure 4B). CAP found no statistical significance when comparing the proportions of separated years (CAP values > 0.05).

A total of 264 (1.0%) patients died during the index hospitalization. Over 80% of deaths were caused by liver-related diseases, including 107 cases (40.5%) of liver failure, 63 cases (23.9%) of HCC, and 27 cases (10.2%) of UGIB. The in-hospital mortality was stable at approximately 1% during the 2011-2020 period (P = 0.372). Meanwhile, 242 patients (1.0%) received LT, and the rate of LT increased by 3.0% during the last ten years (P < 0.001). A total of 1010 patients (4.0%) were admitted to the ICU, and the ICU admission rate increased from 2.7% to 5.0% during the last ten years (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 2). In multivariable regression, as shown in Table 3, transferring from the emergency department resulted in a nearly 3-fold increased risk of in-hospital mortality (adjusted OR: 2.97, 95%CI: 2.01-4.38). MELD scores of 15 or above and older age also increased the risk of mortality (OR: 3.55, 95%CI: 2.24-5.64, and OR: 1.90, 95%CI: 1.28-2.80, respectively). LC complications associated with increased mortality were ascites (OR: 1.74, 95%CI: 1.18-2.56), UGIB (OR: 2.35, 95%CI: 1.59-3.46), HCC (OR: 6.03, 95%CI: 4.07-8.94), ACLF (OR: 4.22, 95%CI: 2.70-6.59), and HE (OR: 3.27, 95%CI: 2.20-4.84). Meanwhile, male gender, LC etiology, medical insurance, LT, and residential areas of patients were not associated with in-hospital mortality (Table 3).

| Characteristics, n = 25150 | Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | ||

| OR | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age2 | 1.49 | 0.011 | 1.90 (1.28-2.80) | 0.001 |

| Gender | 1.25 | 0.230 | 0.93 (0.58-1.49) | 0.761 |

| Etiology | ||||

| Viral hepatitis | 1.10 | 0.583 | -- | -- |

| Alcohol | 0.89 | 0.721 | -- | -- |

| Other etiologies | Reference | -- | -- | -- |

| Referring site | ||||

| Emergency | 6.11 (4.67-7.99) | < 0.001 | 2.97 (2.01-4.38) | < 0.001 |

| Clinic | Reference | -- | Reference | -- |

| Insurance status3 | 1.09 (0.84-1.41) | 0.558 | ||

| MELD4 | 6.85 (5.15-9.09) | < 0.001 | 3.55 (2.24-5.64) | < 0.001 |

| Liver transplantation | 1.22 (0.57-2.63) | 0.764 | -- | -- |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural area | 3.40 (0.84-13.73) | 0.070 | 3.33 (0.81-13.73) | 0.096 |

| Urban area | Reference | -- | Reference | -- |

| Complications | ||||

| Ascites | 2.70 (2.06-3.53) | < 0.001 | 1.74 (1.18-2.56) | 0.005 |

| UGIB | 2.13 (1.62-2.81) | < 0.001 | 2.35 (1.59-3.46) | < 0.001 |

| HE | 10.63 (8.22-13.74) | < 0.001 | 3.27 (2.20-4.84) | < 0.001 |

| HCC | 1.42 (1.15-1.81) | 0.005 | 6.03 (4.07-8.94) | < 0.001 |

| SBP | 4.06 (3.15-5.23) | < 0.001 | 1.34 (0.92-1.96) | 0.123 |

| ACLF | 8.60 (6.73-11.00) | < 0.001 | 4.22 (2.70-6.59) | < 0.001 |

This large sample cross-sectional study showed the transition in etiologies and characteristics of newly diagnosed LC in our medical center during the past two decades. We found that HBV remained the most prevalent cause of LC throughout the study period, but the percentage decreased gradually, especially in people younger than 40 years old. Meanwhile, LC cases caused by ALD and AIH are increasing over time. Regarding clinical characteristics, LC patients are aging and less likely to be decompensated at diagnosis. Moreover, we found that the in-hospital mortality rate was relatively low, and emergency referral, a higher MELD score and LC complications were associated with in-hospital mortality. Since a considerable proportion (52%) of patients are from regions of Southern China other than Guangdong Province, our single-center-based findings may suggest the changing trend of LC etiologies and clinical features in entire Southern China[8].

The viral hepatitis-predominant pattern in etiology in our study is consistent with a global report (42% HBV infection and 21% HCV infection in LC) and some recent studies from other East Asian regions[15,16]. Meanwhile, the > 70% HBV contribution indicated that China is still a highly endemic area of HBV infection. However, the continuous decreases in the proportion of patients with HBV cirrhosis measured every 5-year period in our study reflected an overall descending trend of HBV contribution to LC, which was in line with recent studies from other regions of China[9,17]. The descending proportion should be attributed to the widespread HBV vaccination and the subsequent declining prevalence of HBV in China[4]. Contrast to our results, there was a slight increase of 5.5% in HBV-related LC incidence in China (7.7/100000 in 2000 vs. 8.1/100000 in 2015) according to Global Burden of Disease 2015 study data[5]. However, the same study reported a 38% and 8.8% increase in the incidence of alcoholic-related LC and non-viral non-alcoholic LC, respectively, which would actually result in a relative decrease in the proportion of HBV-related LC when added up. Furthermore, HBV-related LC data in the above study included cases of HBV overlapping with other etiologies, whereas our study defined HBV-LC as mono HBV infection. Considering the difference in etiology definition, our study is supposed to be more accurate to reflect the trend of HBV LC. Given the low prevalence of HBV carriers of only 1.0% among children born after 1999 in China, newly diagnosed cases of HBV LC are expected to decline continuously in the future[18].

Our data showed a continuous increase in the alcoholic LC proportion during the last two decades, while the percentage increased from 5.7% in the 2000s to 7.6% in the 2010s. Alcohol-use disorder is one of the main causes of liver disease-related mortality and accounts for approximately 50% of LC cases worldwide[19]. In China, ALD has become the second leading cause of end-stage liver disease and possesses the highest percentage change in age-standardized incidence among all LC etiologies[5,20]. Significant increases in admissions and the proportion of alcoholic cirrhosis have recently been reported in LC inpatients, and our data are consistent with the data from Northern China[9,17]. Regarding the increasing trend in alcohol consumption over the last three decades in China[21], alcoholic LC cases are expected to continue rising in the future. Our data support the allocation of more resources to reduce the burden of alcohol use disorder.

It is interesting to note that our data showed an increasing trend in the age of LC patients; in addition, a slight but significant increase in the female proportion was also observed (1.5% increase, P = 0.003). Our findings are consistent with a recent nationwide survey from Japan showing a mean age nearly 2 years older when comparing patients from 2015-2017 to patients from 2008-2010 (68.2 years vs. 66.4 years)[7]. Moreover, a hospital-based study from Southwest China reported a nonsignificant increase in the mean age of LC patients from 52.3 years in 2003 to 52.7 years in 2013[22]. Plausible explanations are as follows: first, decreased HBV incidence in young adults and improved survival of LC patients, which resulted in an increased proportion of older patients and more patients admitted at an older age[6]; second, increased incidence of non-viral LC cases, especially alcoholic and autoimmune liver diseases, who were older at diagnosis compared to HBV LC (Supplementary Table 3). Population-based studies in North America have shown decreasing mortality rates of LC, whether for in-hospital mortality or for 1-year mortality, and the benefits may largely be due to improved care[23]. For hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, timely endoscopic treatment and paracentesis and available LT and intensive care have been linked to improved survival[10,24,25]. On the other hand, the increased female proportion can be explained by the decreased proportion of viral hepatitis LC, which has more male patients, and the increased proportion of non-viral LC, especially for AIH LC, which affects more female patients. Moreover, improved health resources to women may also contribute to the increasing female proportion (Supplementary Table 1).

Another notable finding is that the decreasing trend in the HBV proportion is most prominent in patients ≤ 40 years, while the proportions of both young LC patients and young HBV-LC patients are decreasing significantly (Figure 4). Our data are likely to be the outcome of a low prevalence of HBV infection in young adults in China and are also in line with observations from North America[6]. Importantly, the transition has implications for the future because viral hepatitis, especially CHB, is highly associated with liver decompensation and liver cancer[26,27]. Reducing new diagnoses in young people may greatly reduce the burden of end-stage liver disease and liver cancer in the future.

Apart from illustrating the transition of etiologies and clinical features of LC, we also investigated in-hospital outcomes and associated risk factors. The overall in-hospital mortality was 1.0% in our study, which is similar to that in nationwide and regional studies in China[25,28]. In contrast to a decline of 17.6% in the mortality rate of cirrhosis and chronic liver disease in China from 1990 to 2016, we did not observe a descending trend in in-hospital mortality in our study[20]. However, considering the dramatic increase in liver decompensation, LC complications, and ICU admissions in our study population, which indicates an increase in disease severity over time, the observed stable in-hospital mortality is reasonable. In-hospital mortality is considered a hard endpoint of inpatient prognosis and varies across countries. In the 2010s, the reported mortality rates were 5.4% to 7.6% in the United States, 9.1% in Korea, and 11.6% in Spain[23,29-31]. The discrepancy between data from other hospitals and ours may be due to differences in patient selection and criteria for patient admission. Moreover, well-equipped service of intensive care and increased LTs may also contribute to improving patient prognosis[10,23]. Our results are of clinical significance to report satisfactory inpatient care in Southern China.

Reported risk factors for in-hospital mortality included older age, HE, HCC, gastrointestinal bleeding, and sepsis from previous studies[29,31], and our data supported the observation by finding that all major LC complications are associated with poor outcomes. In addition, we emphasized that HCC and ACLF were associated with the highest risk of in-hospital mortality (OR 6.0 and 4.6, respectively) and increased faster than other complications (Supplementary Table 1). Our data are consistent with the increasing trend of HCC and ACLF in China[1,32]. With the rising burden of HCC and ACLF, more attention should focus on early diagnosis and timely treatment of the two severe complications[33,34].

In this study, we revealed the evolution of etiologies and clinical characteristics of hospitalized LC patients over the last 20 years in a large-sample dataset. Meanwhile, we filled the knowledge gap to reveal in-hospital mortality and associated risk factors, which were scarcely reported in China previously. However, there are several limitations to this study. First, as a retrospective study, although we searched cases using both diagnosis codes and literal discharge diagnosis, there are still possibilities of missing cases of LC due to the lack of LC-indicative diagnosis in the original database. Moreover, the retrospective design in HBV endemic region may also result in the underestimation of MASLD, and therefore this study cannot reveal the trend of MASLD-derived LC. Second, different from manual data extraction in the 2001-2010 dataset, data extraction in 2011-2020 is automatic from a single admission note, whereas there are no subsequent data to supplement the diagnosis when the primary etiology cannot be confirmed. The consequent case exclusion due to uncertain etiologies may explain the turbulence in temporal trends in the 2011-2020 period, especially the variance in the proportion of HBV LC between 2010 and 2011. Third, the cross-sectional study did not include follow-up data after patient discharge, so the actual mortality rate over time is unclear. Future studies focusing on trend of prognosis of LC are highly needed. Fourth, the epidemiological indications based on our single-center study are limited, and care should be taken when applying our findings to other countries or regions.

In conclusion, our study showed a decreased ratio of viral hepatitis LC, especially HBV LC, and an increased ratio of alcoholic and AIH LC in real-world inpatients over the past two decades. In-hospital mortality has been low over the last 10 years, and HCC and ACLF are the strongest risk factors for mortality. Further multicenter studies are needed to reveal the actual incidence of LC in China, and more attention should be given to the rising burden of HCC and ACLF in LC patients.

Liver cirrhosis (LC) is the end stage of chronic liver disease and is associated with significant morbidity, mortality and healthcare utilization. China accounts for a large proportion of the regional burden of LC. Thanks to widespread hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination and the potent antiviral treatment for HBV and hepatitis C virus, the LC mortality has greatly decreased.

In the context of changing burden of LC, the recent transition in etiologies and clinical features of LC is unclear in China.

Our main objective was to identify the transition in etiologies and clinical characteristics of hospitalized LC patients in Southern China. Furthermore, in-hospital prognosis and associated risk factors were also investigated.

We included LC inpatients admitted from 2001 to 2020 in this retrospective, cross-sectional study. The etiologies of LC were mainly determined according to the discharge diagnosis, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), portal vein thrombosis, hepatorenal syndrome, and acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) were considered LC-related complications. Changing trends in the etiologies and clinical characteristics were investigated using logistic regression, and temporal trends in proportions of separated years were investigated using the Cochran-Armitage test.

The study included a total of 33143 patients and the mean age increased from 51.0 years in 2001-2010 to 52.0 years in 2011-2020 (P < 0.001). In the meantime, proportion of decompensated LC and the score of model for end-stage liver disease decreased. During the study period, HBV remained the major etiology of LC (75.0%), but the proportion of HBV-LC decreased from 82.4% in 2001-2005 to 74.2% in 2016-2020 (P for trend < 0.001). Meanwhile, the proportions of LC caused by alcoholic liver disease and autoimmune hepatitis both increased slightly (both P for trend < 0.001). In-hospital mortality was low, and HCC and ACLF were associated with 6-fold and 4-fold increased risks of mortality.

Our study showed a decreased ratio of HBV LC, and an increased ratio of alcoholic and autoimmune hepatitis LC in real-world inpatients over the past two decades. HCC and ACLF were identified as the strongest risk factors for in-hospital mortality.

Our large sample cross-sectional study showed the transition in etiologies and characteristics of newly diagnosed LC in our medical center over the past twenty years and the findings may reflect the changing trend of LC in entire Southern China. Future multicenter studies are needed to reveal the changing incidence of LC in China, and more attention should be given to the rising burden of HCC and ACLF in LC patients.

We thank every physician in the Department of Gastroenterology, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University for discussing the manuscript. We thank Tianpeng Technology Co., Ltd. for their contributions and assistance in terms of data extraction.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ferraioli G, Italy; Norton PA, United States S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | GBD 2017 Cirrhosis Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:245-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1158] [Cited by in RCA: 1014] [Article Influence: 202.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Moon AM, Singal AG, Tapper EB. Contemporary Epidemiology of Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2650-2666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 805] [Cited by in RCA: 720] [Article Influence: 144.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liu X, Tan S, Liu H, Jiang J, Wang X, Li L, Wu B. Hepatocyte-derived MASP1-enriched small extracellular vesicles activate HSCs to promote liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2023;77:1181-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xiao J, Wang F, Wong NK, He J, Zhang R, Sun R, Xu Y, Liu Y, Li W, Koike K, He W, You H, Miao Y, Liu X, Meng M, Gao B, Wang H, Li C. Global liver disease burdens and research trends: Analysis from a Chinese perspective. J Hepatol. 2019;71:212-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 64.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Wong MCS, Huang JLW, George J, Huang J, Leung C, Eslam M, Chan HLY, Ng SC. The changing epidemiology of liver diseases in the Asia-Pacific region. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:57-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 6. | Orman ES, Roberts A, Ghabril M, Nephew L, Desai AP, Patidar K, Chalasani N. Trends in Characteristics, Mortality, and Other Outcomes of Patients With Newly Diagnosed Cirrhosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e196412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Enomoto H, Ueno Y, Hiasa Y, Nishikawa H, Hige S, Takikawa Y, Taniai M, Ishikawa T, Yasui K, Takaki A, Takaguchi K, Ido A, Kurosaki M, Kanto T, Nishiguchi S; Japan Etiology of Liver Cirrhosis Study Group in the 54th Annual Meeting of JSH. Transition in the etiology of liver cirrhosis in Japan: a nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:353-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang X, Lin SX, Tao J, Wei XQ, Liu YT, Chen YM, Wu B. Study of liver cirrhosis over ten consecutive years in Southern China. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13546-13555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chang B, Li B, Sun Y, Teng G, Huang A, Li J, Zou Z. Changes in Etiologies of Hospitalized Patients with Liver Cirrhosis in Beijing 302 Hospital from 2002 to 2013. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:5605981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang X, Luo J, Liu C, Liu Y, Wu X, Zheng F, Wen Z, Tian H, Wei X, Guo Y, Li J, Chen X, Tao J, Qi X, Wu B. Impact of variceal eradication on rebleeding and prognosis in cirrhotic patients undergoing secondary prophylaxis. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1495-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3667] [Cited by in RCA: 6888] [Article Influence: 626.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li YM, Fan JG, Wang BY, Lu LG, Shi JP, Niu JQ, Shen W; Chinese Association for the Study of Liver Disease. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of alcoholic liver disease: update 2010: (published in Chinese on Chinese Journal of Hepatology 2010; 18: 167-170). J Dig Dis. 2011;12:45-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Society of Hepatology. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of liver failure. Chin J Hepatol. 2019;27:18-26. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | D'Amico G, Bernardi M, Angeli P. Towards a new definition of decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2022;76:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Alberts CJ, Clifford GM, Georges D, Negro F, Lesi OA, Hutin YJ, de Martel C. Worldwide prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among patients with cirrhosis at country, region, and global levels: a systematic review. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:724-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Sarin SK, Kumar M, Eslam M, George J, Al Mahtab M, Akbar SMF, Jia J, Tian Q, Aggarwal R, Muljono DH, Omata M, Ooka Y, Han KH, Lee HW, Jafri W, Butt AS, Chong CH, Lim SG, Pwu RF, Chen DS. Liver diseases in the Asia-Pacific region: a Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology Commission. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:167-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 74.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bao XY, Xu BB, Fang K, Li Y, Hu YH, Yu GP. Changing trends of hospitalisation of liver cirrhosis in Beijing, China. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2015;2:e000051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liang X, Bi S, Yang W, Wang L, Cui G, Cui F, Zhang Y, Liu J, Gong X, Chen Y, Wang F, Zheng H, Guo J, Jia Z, Ma J, Wang H, Luo H, Li L, Jin S, Hadler SC, Wang Y. Evaluation of the impact of hepatitis B vaccination among children born during 1992-2005 in China. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:39-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Singal AK, Bataller R, Ahn J, Kamath PS, Shah VH. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcoholic Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:175-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 80.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Li M, Wang ZQ, Zhang L, Zheng H, Liu DW, Zhou MG. Burden of Cirrhosis and Other Chronic Liver Diseases Caused by Specific Etiologies in China, 1990-2016: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Biomed Environ Sci. 2020;33:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hu A, Jiang H, Dowling R, Guo L, Zhao X, Hao W, Xiang X. The transition of alcohol control in China 1990-2019: Impacts and recommendations. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;105:103698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xiong J, Wang J, Huang J, Sun W, Chen D. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-related liver cirrhosis is increasing in China: a ten-year retrospective study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2015;70:563-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Kanwal F, Tansel A, Kramer JR, Feng H, Asch SM, El-Serag HB. Trends in 30-Day and 1-Year Mortality Among Patients Hospitalized With Cirrhosis From 2004 to 2013. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1287-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang X, Wu B. Endoscopic sequential therapy for portal hypertension: Concept and clinical efficacy. Liver Res. 2021;5:7-10. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang W, Huang Y, Xiang H, Zhang L, Yuan L, Wang X, Dang T, Zhang G, Hu S, Liu C, Zhang X, Peng L, Gao M, Xia D, Li J, Song Y, Zhou X, Qi X, Zeng J, Tan X, Deng M, Fang H, Qi S, He S, He Y, Ye B, Wu W, Shao J, Wei W, Hu J, Yong X, He C, Bao J, Zhang Y, Ji R, Bo Y, Yan W, Li H, Wang Y, Li M, Lian J, Wu Y, Gu Y, Cao P, Wu B, Ren L, Pan H, Liang Y, Tian S, Lu L, Fang Y, Jiang P, Liu Z, Liu A, Zhao L, Li S, Qiao J, Sun L, Fang C, Chen H, Tian Z, Lin G, Huang X, Chen J, Deng Y, Lv M, Liao J, Lu J, Wu S, Yang X, Guo W, Wang J, Chen C, Huang E, Yu Y, Yang M, Cheng S, Yang Y, Wu X, Rang L, Han P, Li X, Wang F, McAlindon ME, Seto WK, Lv C, Rockey DC. Timing of endoscopy for acute variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis (CHESS1905): A nationwide cohort study. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wan S, Lei Y, Li M, Wu B. A prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma patients based on signature ferroptosis-related genes. Hepatol Int. 2022;16:112-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lei Y, Xu X, Liu H, Chen L, Zhou H, Jiang J, Yang Y, Wu B. HBx induces hepatocellular carcinogenesis through ARRB1-mediated autophagy to drive the G(1)/S cycle. Autophagy. 2021;17:4423-4441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chang B, Li B, Huang A, Sun Y, Teng G, Wang X, Liangpunsakul S, Li J, Zou Z. Changes of four common non-infectious liver diseases for the hospitalized patients in Beijing 302 hospital from 2002 to 2013. Alcohol. 2016;54:61-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Schmidt ML, Barritt AS, Orman ES, Hayashi PH. Decreasing mortality among patients hospitalized with cirrhosis in the United States from 2002 through 2010. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:967-977.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kim HY, Kim CW, Choi JY, Lee CD, Lee SH, Kim MY, Jang BK, Wo HY. Complications Requiring Hospital Admission and Causes of In-Hospital Death over Time in Alcoholic and Nonalcoholic Cirrhosis Patients. Gut Liver. 2016;10:95-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Vergara M, Clèries M, Vela E, Bustins M, Miquel M, Campo R. Hospital mortality over time in patients with specific complications of cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2013;33:828-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yang Y, Li M, Luo J, Yu H, Tian H, Wang X. Non‐hemodynamic effects: Repurposing of nonselective beta‐blockers in cirrhosis? Port Hypertens Cirrhos. 2022;1:153-156. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64686] [Article Influence: 16171.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (177)] |

| 34. | Wang FS, Fan JG, Zhang Z, Gao B, Wang HY. The global burden of liver disease: the major impact of China. Hepatology. 2014;60:2099-2108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 985] [Cited by in RCA: 944] [Article Influence: 85.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |