Published online May 27, 2022. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v14.i5.896

Peer-review started: February 24, 2021

First decision: June 15, 2021

Revised: June 29, 2021

Accepted: April 8, 2022

Article in press: April 8, 2022

Published online: May 27, 2022

Processing time: 453 Days and 15.3 Hours

It is increasingly recognised that collecting patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) data is an important part of healthcare and should be considered alongside traditional clinical assessments. As part of a more holistic view of healthcare provision, there has been an increased drive to implement PROM collection as part of routine clinical care in hepatology. This drive has resulted in an increase in the number of PROMs currently developed to be used in various liver conditions. However, the development and validation of a new PROM is time-consuming and costly. Therefore, before deciding to develop a new PROM, researchers should consider identifying existing PROMs to assess their appropriateness and, if necessary, make adaptations to existing PROMs to ensure their rigour when used with the target population. Little is written in the literature on how to identify and adapt the existing PROMs in hepatology. This article aims to provide a summary of the current literature and guidance regarding identifying and adapting existing PROMs in clinical practice.

Core Tip: In the last few years, there has been a rapid increase in the number of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in hepatology and, therefore, the choice between which of these PROMs to use can be difficult. This paper aims to illustrate ways of identifying existing PROMs and outlines key considerations and good practice with respect to their adaptation in clinical practice or research in hepatology.

- Citation: Alrubaiy L, Hutchings HA, Hughes SE, Dobbs T. Saving time and effort: Best practice for adapting existing patient-reported outcome measures in hepatology. World J Hepatol 2022; 14(5): 896-910

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v14/i5/896.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i5.896

Patients are treated by healthcare providers with the primary goal of improving their health and well-being. Historically this improvement in health has been judged by improvement in biochemical, histological, radiological or clinical assessments. This approach does not always correlate with improvement from the patient perspective. From a patient perspective improving health is reflected in the documentation of their symptoms and experience of healthcare provision, which are more appropriately collected directly from the patient[1]. With a move towards shared-decision making and patient-centred care, there is growing recognition within the healthcare community of the importance of the patient perspective and the need to consider patient reported outcomes (PRO) as a key component of a holistic approach to patient care.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines a PRO as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else”[2]. The European Medicines Agency state that “Any outcome evaluated directly by the patient himself and based on the patient’s perception of a disease and its treatment(s) is called a patient-reported outcome (PRO)”[3]. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) can be broadly classified as generic or disease-specific instruments. Generic PROMs assess general aspects of health and can be applied across multiple conditions. Disease-specific PROMs, on the other hand, assess specific aspects that are related to a particular condition. PROMs are designed to measure aspects of health that can neither be directly observed or are not feasible to observe[4]. Broadly speaking, collection of PROMs from the patient can be classified into three main categories based on the outcomes measured: Health status and quality of life: patients’ health and well-being as indicated by patient report; Patient satisfaction: patient-reported satisfaction with their medical treatment or care; Resource use: patients’ reported use of health services and resources; Patient knowledge questionnaires: patients’ understanding of medical conditions and the treatment.

PROMs were initially developed for research use and many regulatory authorities such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the FDA advocate their use[2,5,6]. Recent consensus guidance also recommends the inclusion of PROMs in clinical trial designs[7]. The collection of PROMs aligns well with the increased drive within healthcare organisations for value based healthcare, whereby organisations aim to achieve the best possible outcomes for patients with the available resources[8]. As more clinicians recognise the benefit of collecting PROMs in addition to measuring clinical outcomes, PROMs have seen an increased use in routine clinical practice[9].

As a consequence of the drive to collect PROMs, there has also been an increase in the number of PROMs developed, validated, and used. The King’s Fund report reflects on this as ‘‘a growing recognition throughout the world that the patient’s perspective is highly relevant to efforts to improve the quality and effectiveness of health care’’ and that PROMs are likely to become ‘‘a key part of how all health care is funded, provided, and managed’’[10]. This has been illustrated in the United Kingdom when, in 2009, the United Kingdom Government implemented the routine collection of PROMs in England for four routine elective surgical procedures — hip and knee replacement, groin hernia repair, and varicose vein surgery (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-tools-and-services/data-services/patient-reported-outcome-measures-proms), in order to compare performance between providers. It is likely that routine PROMs collection will be extended to more conditions in the future.

In order to identify relevant literature regarding best practice and guidance for the adaptation of existing PROMs we undertook a scoping review of the literature. This scoping review aimed to explore the extent of the literature within the PROMs field regarding best practice/guidance for PROM adaptation without describing findings in detail[11,12].

We undertook a review of the literature to identify key papers/guidelines for the adaptation of existing PROMs. We searched PubMed and the Cochrane database (https://www.cochrane.org/). In order to limit the search, we searched for literature in the English language published within the last 10 years. Reference lists of relevant identified publications were also hand searched to identify further relevant literature. We also undertook a GoogleTM search to identify relevant publications.

Details of the search strategy are presented in Table 1. The searches were conducted on 17 February 2020. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 2.

| Keyword combinations | ||

| Patient Reported Outcome Measures OR patient reported outcome measure1 OR PROM1OR PRO1 OR patient reported outcome1 OR patient outcome1 OR clinical outcomes assessment | AND | Guidance OR guidelineOR recommend1 OR good practice OR best practice OR instrument development OR adapt1 OR modif1 OR develop1 OR establish1 OR efficien1 OR standard1 OR measurement properties |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| (1) Articles presenting guidance and recommendations for use or adaptation of existing PROMs; and (2) PROMs methodology papers | (1) Papers detailing development and validation of new PROMs; (2) Papers not presenting guidance or recommendation for adaptation of PROMs; (3) Study protocols; (4) Papers that focus on implementation of PROMs in research or clinical practice; (5) Conference abstracts; (6) Not published in English; or (7) Published longer than 10 yr ago |

We carried out an initial title screening, then abstract screening to identify relevant papers that fitted the inclusion criteria, which we then reviewed fully. We identified specific themes related to the adaptation of existing PROMs which we regarded as recommendations/good practice and have structured the paper according to these identified themes.

Supplementary Table 1 illustrates the publications identified as part of the scoping review of the literature. The guidance identified within these publications is organised under the specific headings of: defining the requirements of a PROM, identifying and appraising existing tools, adapting existing PROMs, issues of content validity and getting the right people involved.

In order to provide meaningful information, PROMs need to be appropriately developed and validated according to robust criteria. The psychometric validation of PROMs can be complex and time-consuming and requires evidence of numerous facets including validity, reliability and responsiveness[13,14]. Given the growth in the number of available PROMs, even within the same condition, the old adage “don’t reinvent the wheel” should be the first principle applied before taking the decision to embark on the development of a new PROM. Consequently, to enable researchers to appraise the quality of existing measures with the aim of ascertaining whether a new measure is needed, researchers must first establish a clear definition of what is required of the PROM.

The requirements of the PROM need to be identified at the outset[15]. Consideration should include what the PROM aims to measure, whether the PROM should be generic or disease specific, the clinical condition of interest, the specific population for which the PROM will be applied and whether it will used as part of routine clinical care or research. These factors will help to determine whether existing PROMs are suitable or can be adapted. A useful overview and starting point for deliberations is provided by Luckett and King[16].

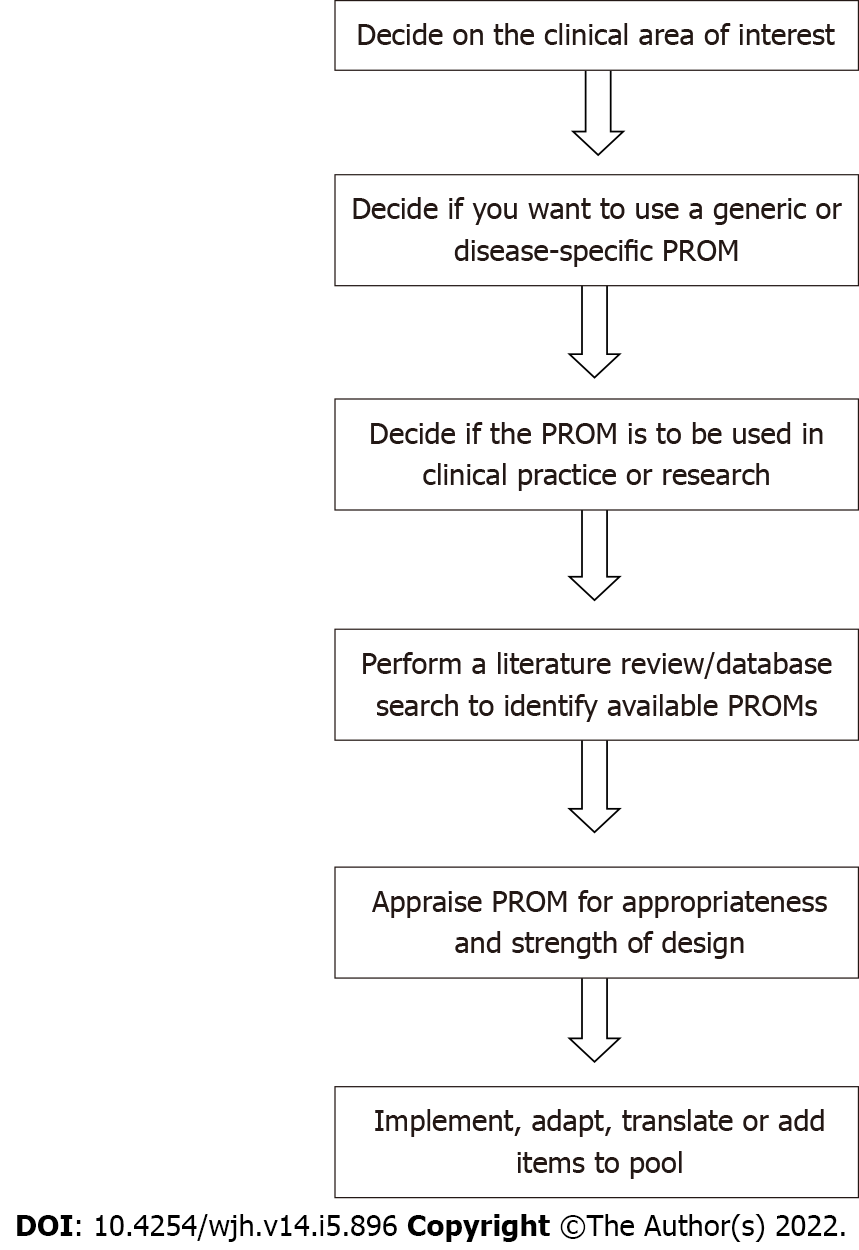

A generic PROM may allow comparison of patient outcomes across different conditions, however it will have less focus on specific symptoms relating to a condition. A disease-specific PROM will have a more defined focus on the condition itself and will be more sensitive to changes in the condition over time and its associated symptoms but may be longer and therefore the burden to the patient may be greater. If a disease-specific PROM is required, one needs to define the specific population. For example, a PROM developed to measure pruritus in primary biliary cholangitis may not be suitable for measuring pruritus in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy as the patient experience of dyspnea may differ across these two clinical conditions[2,16]. It is also important to consider whether the PROM will be used within a routine clinical setting or a research setting[17]. In a clinic setting where time may be limited, the burden to the patient and the feasibility of completing the PROM need consideration. Within a research setting, time may not be as limited and longer, more detailed PROMs can be considered[17]. The proposed method of administration of the PROM is also important and authors planning on using a PROM should ensure that it has been appropriately validated for their proposed administration method[2]. Issues such as respondent and administrator burden — length, formatting, font size, instructions, privacy, literacy levels etc. also need to be considered[2]. Figure 1 provides an overview of the first steps required before choosing to develop a new PROM.

Luckett et al[16], have provided useful principles to consider when selecting a PROM: Selection of PROMs should be considered early during study design — selection should be driven by the research objectives, samples, treatment and available resources; For the primary outcome, choose as ‘proximal’ a PROM as will add to knowledge and inform practice — ‘proximal’ (symptoms) vs ‘distal’ (overall quality of life); Identify candidate PROMs primarily on the basis of scaling and content — which items/scales offer best coverage of the impacts of interest and which aspects of score distribution will be most meaningful to consider? Appraise the reliability, validity and ‘track record’ of candidate PROMs — look beyond articles that focus on evidence of validity and reliability; Look ahead to practical considerations — patient and staff burden, methods of administration, cost, availability of translated versions, guidelines for scoring and interpretation; Take a minimalist approach to ad hoc items — where content is similar, PROMs with proven psychometric properties are preferable to ad hoc measures developed by the researcher[17].

The EAPC[17] have provided guidance regarding the selection and measurement of PROMs in palliative care. This guidance reflects on the content of the PROM and the feasibility of its collection within the clinical environment. Some of the points made are particularly useful when considering adapting existing measures and can be usefully applied to other conditions: Use PROMs that have been validated with relevant populations and make sure these are sufficiently brief and straightforward; Use multi-dimensional measures; Use measures that have sound psychometric properties; Use measures that are suited to the clinical task being delivered and are also suited to the aims of your clinical work and the population you work with; Use valid and reliable measures in research that are relevant to the research question and consider patient burden when using measures[17,18].

Once one has defined the scope of the PROM, possible candidate measures can be identified. This process will determine whether there is a need for a new PROM. It will also allow for the identification of PROMs that could, be adapted, shortened, translated or expanded.

Given the large number of available PROMs, there are several ways in which possible candidate PROMs may be identified. Identifying systematic reviews of PROMs for a particular clinical area may prove to be particularly fruitful as good reviews will assess the methodological quality[13-16] of the PROMs identified and provide a summary of the PROMs that offer the most promise. In addition to undertaking literature reviews, there are also databases and online resources that can be searched to identify existing PROMs. Some of these resources are generic and cover many conditions, whilst others provide a resource for disease-specific PROMs. Table 3 provides some examples of resources that can be used to identify candidate PROMs for adaptation.

| Resource name and web address | Resource Information |

| ePROVIDETM (https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/) | This is an online service provided by Mapi Research Trust and is the official licensor and distributor of more than 450 clinical outcome assessments (or PROMs). This resource allows you to search for PROMs within a specific clinical area and presents: a summary of each tool; the authors of the tool; different version of the questionnaire; the copyright owner; the specific condition/disease in which the PROM has been used; the original language the PROM was developed in; references to the original PROM development publications; and a list of any validated translations of the original questionnaire. If a PROM is deemed appropriate but no valid translation exists, there is also an opportunity to submit a request to undertake a linguistic validation of the questionnaire |

| COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) (https://database.cosmin.nl/) | The COSMIN initiative (https://www.cosmin.nl/) aims to “develop methodology and practical tools for selecting the most suitable outcome measurement instrument). Their mission statement is: “to improve the selection of outcome measurement instruments of health outcomes by developing and encouraging the use of transparent methodology and practical tools for selecting the most suitable outcome measurement instrument in research and clinical practice”. The COSMIN website provides a link to the COSMIN Database for Systematic Reviews which can be searched to identify literature reviews that have been undertaken within specific clinical areas. The database provides a summary of the review and the PROMs that formed part of the review and links to the original publications. Examination of these reviews is useful in assessing whether an existing PROM may be appropriate to use. Many of these reviews will also present a synthesis of each PROM with an assessment of its methodological quality and validity according criteria outline in more or more of the guidance documents available[2,44,61-65] |

| International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement (ICHOM) (https://www.ichom.org/) | As part of a wider initiative ICHOM publish Standard Sets. ICHOM Standard Sets are defined as ‘standardized outcomes, measurement tools and time points and risk adjustment factors for a given condition. Developed by a consortium of experts and patient representatives in the field, our Standard Sets focus on what matters most to the patient’ |

| Measures for Person Centred Coordinated Care (http://p3c.org.uk/about) | Set-up as a result of an NHS England funded project. This online resource describes itself as providing information “about measures for Person Centred Coordinated Care (“P3C”) for people with long-term conditions (LTCs), multiple-LTCs, and those at the end of their life (EoL)”. It provides a compendium of measures — defined as PROMs and patient reported experience measures (PREMs) — that can be utilised within programs that aim to deliver or evaluate P3C in the target populations” |

| European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) (https://www.eortc.org/tools/) | Amongst other resources, the EORTC website provides a list quality of life questionnaires that have been developed and validated for cancer patients that are available for academic use |

| Oxford University Innovation/University of Oxford Clinical Outcomes Assessments (https://innovation.ox.ac.uk/clinical-outcomes/patient-reported-outcomes-measures/) | The PRO portfolio is made up of condition-specific questionnaires aimed at assessing the outcome for patients being treated for a range of medical conditions |

If these strategies do not identify any PROMs, conducting a new systematic review may uncover PROMs for consideration or items/questions in existing PROMs that could be included in the development of a new PROM[14]. Prinsen et al[13], have formulated a useful ten step process for conducting such systematic reviews of PROMs[13,14]. Such a systematic review should be conducted in accordance with the guidelines outlined by internationally recognised COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN). COSMIN provide detailed information and tools to aid this process on their website (https://www.cosmin.nl/tools/guideline-conducting-systematic-review-outcome-measures/). This will ensure that the methodological rigor of the PROMs identified is appropriately appraised.

Once PROMs have been identified, the tools should be reviewed for their content and appropriateness for the desired application[13,14-22]. This process will also help to identify relevant questions/ items that could be used to develop a new PROM or adapt an existing one.

Researchers need to consider the existing PROM literature to determine whether an adequate instrument exists to assess and measure the concepts of interest. If no PROM exists, a new PROM can be developed or in some situations, a PROM can be adapted by modifying an existing instrument[2].

Examples of instrument modifications include: (1) Making minor cultural/Language adaptations within the same source language; (2) Undertaking a cross-cultural adaptation that includes translation into a different language; (3) Including additional items/questions; and (4) Shortening the original instrument. Such PROM modification may be necessary to enable the PROM to be used with a different population or with a different population age group (for example, modification of an adult PROM for a paediatric population), to facilitate its use in a different language, for use in a different disease stage or treatment (for example cancer stage, or for a newly diagnosed condition rather than a pre-existing condition), or to reduce patient burden.

The FDA state that when a PROM is modified, evidence of adequacy for its new intended use should be provided and that “additional qualitative work may be adequate” to test such modifications[2]. Such changes include: Changing an instrument from paper to electronic format; Changing the application to a different setting, population or condition; Changing the order of items, item wording, response options, or recall period or deleting portions of a questionnaire; Changing the instructions or the placement of instructions within the PROM.

Snyder et al[21], outline some requirements to revalidate a PROM when changes such as these are made to an existing PROM.

The search for PROMs may identify existing instruments that have proven validity for the population being studied and can be applied without requiring any adaptation. Alternatively, a PROM may be identified that appears appropriate but requires modification. Before engaging in any adaptation, it is important first to contact the PROM developer/copyright holder to ask for permission to make changes to the original PROM. Wild et al[22], have recently published guidance from the International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL) Translation and Cultural Adaptation Special Interest Group (TCA-SIG) regarding copyright of PROMs. Failure to gain appropriate permissions for use and adaptation may result in legal challenges due to breaches in copyright. The authors present recommendations to prevent future conflict that includes: Protecting the copyright of the original PROM; Writing a contract; Taking care when publishing; Establishing rules; Making the copyright notice visible; Maintaining copyright of the PROM and any derivatives with the original author; Centralising distribution; Getting legal counsel; Clarifying the copyright situation with respect to legacy PROMs.

It is therefore prudent for researchers considering the adaptation (including the translation of existing PROMs) to identify and obtain agreement from the copyright holder prior to any adaptation[22].

If a suitable PROM is identified and has appropriate content validity for the population of interest, but was developed and validated in a different language, cross cultural adaptation represents an efficient way of adapting an existing PROM. Cross-cultural adaptation manages language translation and cultural adaptation issues with the aim of ensuring a PROM is sensitive to the linguistic and cultural needs of the target population[22]. A PROM that has undergone rigorous cross-cultural adaptation is suitable for use in multinational and multicultural studies.

It is important that any cross-cultural adaptations of PROMs are undertaken rigorously. Guidance regarding the process of cross-cultural adaptation has been described in a wide range of publications[22-25]. The lack of ‘gold standard’ guidance for cross-cultural validation prompted the Patient Reported Outcome (PRO) Consortium, to update and develop further guidelines for best practice in the translation process[26]. These guidelines are based on the ISPOR Task Force guidelines, updated with greater detail through a further consensus process[22].

The aim of cross-cultural adaptation is to provide equivalence between the source PROM and the adapted version. Equivalence has many definitions; however, most current guidelines follow the universalist approach proposed by Harachi et al[27], which gives consideration to the influence of culture on how people respond to any given item on a questionnaire. Questions therefore not only require linguistic translation, but they must also be adapted to fit culturally to the target country[26]. For example, a question about difficulty using a fork in eating may not be applicable in a country where a fork is not used in eating[28]. Equivalence can be divided into five categories plus a summary category[22,28] (see Table 4), and this has formed the basis of many guidelines for the cross-cultural adaptation of outcome measures.

| Categories | |

| Conceptual equivalence | The domains of the questionnaire have the same relevance, meaning and importance in both cultures |

| Item equivalence | Individual items have the same relevance in both cultures |

| Semantic equivalence | The meaning of the items is the same in both cultures |

| Operational equivalence | The questionnaire can be used in the same way by the target population in both cultures |

| Measurement equivalence | The two versions have similar psychometric properties |

| Functional equivalence | This is meant as a summary category of the preceding five categories. It is an overall statement that identifies if both versions “do what they are supposed to do equally as well” |

Ultimately, all of the available guidelines are broadly based on a core set of principles that need to be considered when cross-culturally adapting an existing PROM: (1) Preparation. The initial stage of the process is to identify the team that will be responsible for the work, identify suitable translators and gain permission from the original instrument design team to carry out a translation process; (2) Forward translation. Translation of the original language version into the new, target language. It is considered best practice for this to be performed at least twice by different translators from the target country; (3) Reconciliation. Comparison of multiple forward translations and merging them into one translated version; (4) Back translation. The newly translated version is translated back into the original source language; (5) Back translation review. The back-translated version is compared to the original version to assess for equivalence in text and meaning; (6) Harmonisation. All translated versions are reviewed for consistency in language and conceptual meaning; (7) Proofreading. All copies of the questionnaire are proofread to remove mistakes; (8) Cognitive interviewing. The newly translated questionnaire is piloted on a minimum of five people in the target population. Cognitive interviews are performed to identify problems with the questionnaire, difficulties in understanding and meaning of items and any other concerns; (9) Cognitive interview review. Results of the cognitive interviews are reviewed and changes made to the questionnaire if required; (10) Final review and publication. The final version of the translated questionnaire is agreed upon and published for use in the target population; and (11) Cross-cultural validation. Following the production of a culturally and linguistically valid and similar version of the original questionnaire, the adapted questionnaire must then be psychometrically validated against internationally recognised criteria[28,29].

The degree of cross-cultural adaptation required varies depending on the proposed use of the adapted PROM. The intended use of the PROM may influence the number of steps of the above that require completion[29]. Table 5 illustrates five different scenarios where differing adaptation needs are required[25,29]. These range from a situation in which no adaptation is required (i.e., the questionnaire used in the same population, in the same culture and language as originally designed), to full translation and cross-cultural adaptation (i.e., where the questionnaire is to be used in a different country and language).

| Results in a change in | Adaptation required | ||||

| Culture | Language | Country of use | Translation | Cultural adaptation | |

| Use in same population. No change in culture, language or country | - | - | - | - | - |

| Use in established immigrants in source country | Yes | -- | - | - | Yes |

| Use in another country, but same language | Yes | - | - | - | Yes |

| Use in new immigrants, not source language speaking but in the source country | Yes | Yes | - | Yes | Yes |

| Use in another country and another language | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

If an existing PROM is identified as largely meeting the requirement for the population of interest but following patient and expert consultation and/or exploration of the literature it is perceived to be missing in one or more key areas, there is the potential to adapt the PROM by adding new questions/items. There are various ways in which items can be sourced[17,28]: By asking patients. Patients can be asked to identify additional items and domains that do not exist in the current version of the PROM. Patients are essential to item generation, ensuring item content is both relevant and provides full coverage of the target construct. Qualitative methods such as patient focus groups, interviews and surveys are useful for generating potential new items[30-32]; By evaluating the PROMs identified as a result of reviewing the literature or online resources. This can be an efficient way to generate new items. There are benefits to sourcing items in this way, most notably that there are likely to be a limited number of ways to ask questions about a specific problem such as abdominal pain, vomiting, etc. Moreover, items in existing PROMs have been repeatedly used and validated in many studies and trials; By identifying possible items from clinical observations. These items can be derived by clinicians based on their experience; By asking experts. This is a commonly used approach to generate new items. Similar methods (for example interviews, focus groups and surveys) to those used with patients can be used for gathering information about possible items for inclusion. Although useful for generating items, expert involvement should be used in tandem with other methods and should not be used in place of patient input; By utilising item banks. Item banks are a source of validated items that can be added to existing PROMs. One such item bank, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMISTM) initiative was established in 2004, with the main goal of developing and evaluating, for the clinical research community, a set of publicly available, efficient and flexible measurements of PROs[33]. PROMISTM (http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis/List-of-adult-measures) provides item banks that offer the potential for PRO measurement that is efficient (minimizes item number without compromising reliability), flexible (enables optional use of interchangeable items), and precise (has minimal error in estimate) measurement of commonly-studied PROs[33]. The PROMIS group has developed and tested several hundred items measuring 11 health domains[33]. These core PROMIS domains reflect common, generic symptoms and experiences that are likely to apply to people in a variety of contexts or with a variety of diseases[33]. With additional validation, these banks may provide a common metric of represented constructs across a range of patient groups, thereby reducing the large number of different measures currently used in research and allowing researchers to compare these constructs across patient groups in different studies[33].

Although many single-item and short-form symptom measures exist, one reason for adapting an existing PROM is to shorten it and reduce the number of items included in it. This can result in reduced patient burden and facilitate the use of a PROM as part of routine clinical care. As with other aspects of adaptation, it is essential to ensure that a shortened PROM is comprehensible to patients, includes all the relevant items and is fit for purpose. Like cross-cultural adaptation and adding existing items to a PROM, shortening will require further psychometric testing according to recognised criteria[30].

Where any adaptation is planned, the PROM will still need to show evidence that it is ‘fit for purpose’ with the intended population[33]. In 2007, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Health Science Policy Council recommended that an ISPOR Patient-Reported Outcomes taskforce on the use of existing instruments and their modifications be established. This resulted in the publication in 2009 of their report detailing good research practices[16]. A major aspect of this report related to the content validity of PROMs, and stated “evidence of content validity should be obtained from an analysis of the relationship between the instrument’s content and the construct it intends to measure”[16]. This report highlights the key issues relating to content validity issues that should be considered when selecting and modifying existing PROMs[16]: Name and define the concept; Target population and end point; Identify candidate PROMs; Identify or formulate a conceptual framework for the PROM; Assemble and evaluate information on development methods — elicitation focus groups and interviews; cognitive interviews; transcripts; Conduct any needed qualitative work; Assess adequacy of content validity for purpose; Determine the need for modifications or new PROM development.

This guidance has since been updated to include further recommendations from the ISPOR good practice task force[34]. Additional guidance regarding content validity and its consideration with respect to PROM development and adaptation have also been published and includes best practices for undertaking qualitative research to explore content validity, including differences between establishing content validity for new measures compared with existing measures[14,35].

Assessment of PROM content is an important process when adapting an existing PROM and this should involve engagement with, most importantly, patients and also clinicians.

Having identified a candidate PROM for adaptation it is important to ensure that it is appropriate for the patient population being studied. This is particularly important to undertake if the PROM is being adapted for use with a new clinical population. Pre-testing the PROM with patients, clinicians, and subject-matter experts will provide evidence of the PROM’s content validity and help to ensure that any problems are rectified prior to applying the PROM in a large-scale study or implementing the instrument in routine clinical practice.

In 2009 FDA guidance suggested that an important first step in establishing that a measure is fit for purpose is to develop a conceptual framework for the PROM and generate relevant items on the basis of direct input from patients with the clinical disease[2,34,35].

Recent guidance[36,37] highlights the various roles that patients and patient advocates can play in PROM studies. These include: PROM design and selection — bringing knowledge of the disease, symptoms and attributes of care with the greatest impact on patients’ lives; PROM implementation and administration — the patient can bring insights based on their experience to guide practical decisions around PROM administration and implementation; Linguistic and cultural input — patients can contribute to the language used in the PROM to ensure it is straightforward and understandable to patients.

Guidance regarding how the patients can be recruited to PROM studies, how to engage with patients, defining the role, provision of training and remuneration[38] has also been provided.

In addition, a framework for fully incorporating public involvement (PI) into PROMs has recently been published[38] which illustrates the extent to which patients can be involved in the adaptation process (see Table 6).

| Stage | How can PI be involved |

| Establishing a need for a new or refined PROM | Review existing PROMs; Critique existing PROMs; Determine whether a new PROM is needed |

| Development of a conceptual model | Review of conceptual model to ensure validity |

| Identifying item content | Input on study design; Input on culturally appropriate issues; Input on participant facing documents; Input on ethics and governance issues |

| Item development | Analysis and interpretation of qualitative interviews; Advice and input on wording of potential items |

| Item reduction | Identify potentially redundant items; Identify items that could benefit from rewording; Input and advice on ordering of items |

| Pre-testing of items (cognitive interviews/debriefing) | Input on study design, methodology, recruitment, design and content of public facing documents and conducting the interviews; Analyse and/or interpret results |

| Selection of items for the PROM | Advice on final selection of items; Consideration of number of items to be included; Advice and input into how PROM may be used in clinical settings |

| Design of the PROM | Advice and input on format and layout of PROM; Advice on instructions of how to complete the PROM, framing of questions, wording of response options, and order of items |

Existing measures can be reviewed to ensure they match the domains of interest and if further modification may be required[16]. Recent research that explored the level of involvement of patients in the development of PROMs has concluded that what patients consider important can differ from what health-professionals regard as important[30,31]. Content validity is often cited as a PROM’s most important measurement property as unless the PROM can be shown to be measuring the construct of interest from the patient perspective, all other measurement properties may be considered inconsequential[13]. This highlights the importance of engaging with patients as part of the PROM adaptation process.

A variety of qualitative methods can be used by researchers to engage with patients with the aim of maximising a candidate PROM’s content validity (relevance and comprehensiveness) and to pre-test an adapted PROM for comprehensibility and acceptability of instructions to respondents, its items and response format(s). In a recent study examining the developers’ perspective of including patients, the methods used were interviews and/or focus groups, cognitive interviews and feedback questionnaires[30,31]. Maitland and Presser advocate a diverse range of methods, both qualitative and quantitative, for appraising the quality of PROM items and the ability of the items to generate reliable and valid responses[39].

Interview and focus groups are often used to gain insight into the experiences of the target population in relation to the construct of interest and, therefore can be used to generate content for new or additional questions. Cognitive interviews, on the other hand, are normally used to refine item candidates and their response scales. Cognitive interviews capture problems with the cognitive processes associated with item response[40], thereby enabling the developers to evaluate the relevancy, comprehensiveness, comprehensibility and acceptability of the instrument’s items and response scales.

Feedback questionnaires can also provide patients insight regarding their experience of using a health status questionnaire. The QQ10 is one such validated, self-completed questionnaire. It is made up of 10-items scored using a 5-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree) covering two factors, “value” and “burden”. It contains specific items developed to assess a PROM’s content validity (i.e., relevance, comprehensiveness) from the patient perspective[41,42].

The assessment of a candidate PROM from the expert clinical, researcher and academic perspective is also important. This can be achieved via focus groups and interviews, by questionnaire survey methods or by employing expert review panels[34]. Ideally, these panels should include clinicians with experience of treating the defined population, PROMs methodologists and researchers. The COSMIN standards recommend a minimum sample size of seven professionals for studies evaluating a PROM’s content validity[14].

Experts can also be utilised to calculate content validity indices (CVI) based on ratings of item relevance. A minimum of three experts is recommended for the purposes of calculating a CVI[43]. A CVI is a consensus indicator of the content validity of an item or scale[44]. It represents the proportion of reviewers who agree that an item is content valid, adjusted for chance agreement. If all reviewers are in agreement, the CVI value for an item (I-CVI) will be 1.00.

Employing different psychometric methods to PROMs development and adaptation

Traditionally the development and psychometric evaluation of PROMs has been based on classical test theory (CTT). CTT is probably still the most commonly applied method in validation studies[20,45]. CTT assumes that the expected value of all the random error will equal zero[46]. There are, however, some disadvantages with CTT, such as sample dependency. This is where the item and scale statistics can only in theory, apply to the specific group of patients who took the test and as such further validation is required for a different population[29]. There is also the assumption of item equivalence, where it is assumed that all items contribute equally to the final test score and no item weightings are applied[46,47].

As a result of the disadvantages of CTT, modern psychometric methods of item response theory (IRT) and Rasch measurement theory (RMT) have been developed[48]. Rather than considering the questionnaire as a whole, as in the case of CTT, these methods allow analysis at the individual item level[49]. They also provide sample-free measurements (i.e., the results are applicable to all similar groups once the validation process has occurred). In IRT, additional model parameters are used to model the relationship between the individual’s trait, the item property and the probability of endorsing an item. The assumption in IRT is that the “probability of answering any item in the positive direction is unrelated to the probability of answering any other item positively for people with the same amount of the trait” [28,29]. RMT differs somewhat in that the data are assessed to see if they fit the Rasch model. RMT allows for the creation of linear, interval-level measurement from categorical data. In the case of non-fitting data (items or persons), data can be further examined to understand why they do not fit or removed from the data set. Rasch analysis can be used to examine the properties of previously constructed scales as well as in the construction of new scales, and is important in making interval scales[50].

Although there has been a general shift towards using IRT in more recent years for developing and validating a PROM, there are some drawbacks to its use over CTT. One issue relates to the sample size required. It is recommended that sample sizes based on CTT should be large enough for the descriptive and exploratory pursuit of meaningful estimates from the data, starting with a sample of 30 to 50 subjects may be reasonable in some circumstances[51]. At later stages of psychometric testing, various recommendations have been given for exploratory factor analyses with recommendations of at least five cases per item and a minimum of 300 cases or to enlist a sample size of at least 10 times the number of items being analysed, so a 20-item questionnaire would require at least 200 subjects[51]. For IRT, sample sizes of a minimum of 150-250 patients has been proposed, with around 500 patients recommended for the latter stages of validation[51,52].

In addition to the inflated sample size recommendations for IRT, additional expertise in the study team is often required, and this may consequently result in greater development costs. Furthermore, strict assumptions in the model can mean that items may be rejected even when they have good content validity if they do not fit the IRT model. CTT should therefore not be disregarded and indeed, most authorities will agree that aspects of both CTT and IRT have a role to play in the validation process of a modern PROM.

Most health providers treat patients with the aim of improving radiological, biochemical, histological and clinical assessments[1]. Historically, health outcomes have focused on death or clinical indicators such as infection rates, readmissions, re-operations and adverse events[10]. Many of the symptoms that are experienced by patients in hepatology may be undetected by clinical tests or underestimated by clinicians[53]. The need to assess the impact of health treatment on patients and to demonstrate the value of the care provided to the patient by the provider is now recognised[9]. There is constant pressure on healthcare providers to improve the quality of healthcare provided and make it more patient-centered[54]. Given how much money is spend on treatment, it is important to assess if the treatment given offers value for the money. Clinical applications of PROMs can be divided into: Clinical research and trials: Health regulatory bodies such as the FDA and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) require PROMs to be incorporated into the assessment of new treatments, health technologies or medical devices; Quality improvement projects: PROMs can be very helpful in assessing the impact of a new service or project from the patient perspective. However, PROMs must be integrated into clinical practice with strong incentives to encourage their routine use in such quality improvement projects; Clinical practice: Measuring PROMs in clinical practice contributes to patient-centeredness and measures clinical effectiveness from a patient perspective.

There has been widespread adoption of PROMs use within the research field, especially since FDA and EMA recommended that PROMs should form part of the outcome assessment for new drug trials[2,5]. Reporting guidance for PROMs has also now been incorporated as an extension to CONSORT reporting for trials[7]. The value of collecting PROMs data routinely is now recognised as an important part of driving the delivery and organisation of healthcare and can thereby help to improve healthcare quality[9].

Although individual hospitals and clinicians have started to implement routine PROM collection, widespread adoption is largely restricted to England, Sweden and parts of the United States[9,55]. PROMs have now been implemented in England for the routine collection following some elective surgery (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-tools-and-services/data-services/patient-reported-outcome-measures-proms). Their potential to be used in other clinical areas, such as oncology[56,57], multiple sclerosis is now also recognised. The routine collection of PROMs is not without its challenges however[1,9,55-60].

Some of the practical challenges to routine integration include: the selection of the most appropriate tool; difficulties with patient completion (for example, lack of comprehension, elderly and frail or sick populations); clinical reluctance; achieving high rates of patient participation; operational difficulties; lack of clarity about the PROM; times pressure for patients and clinicians; lack of human resources; recognition of the three dimensions of quality (safety, effectiveness and experience); attributing outcomes to the quality of care; providing meaningful outputs from PROMs data for differing audiences; and avoiding misuse of PROMs[1,9,55,59-65].

McDowell and Jenkinson[66], have developed a series of key strategic priorities that should be considered when implementing PROMs in real-world situations: Ensure international collaboration across multiple stakeholders to agree on a standardised approach to PROM assessment; Develop a comprehensive standard set of recommendations, methods and tools that are applicable to the generation of real-world evidence; Formulate a clear governance process including an ethical framework for how patients should be consented, who selects patients, who has access to data and how data will be used; Establish standard sets of PROMs, electronic tools and administration schedules; Develop and use electronic PROMs where possible; Minimise workload and technical complexity for patients and clinicians; Consider the objectives of the PROM assessment, timings, length of follow-up, strategies for managing missing data and inclusion of diverse patient populations; Ensure data collection adheres to the FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable) guidance; Provide guidance on interpretation and use of the data; Ensure both patients and clinicians gain value from PROM collection to tailor their needs.

With new treatment and technologies, mortality is reducing and more patients are living with their illness for longer. As such, there is a growing need to develop and implement PROMs to facilitate the translation of clinical research into practice and, in keeping with the principles of shared clinical decision-making as part of routine clinical practice.

The increased use of digital media presents an exciting opportunity for PROM capture and adaptation. By utilising new technologies to aid PROMs capture and support interpretation, more clinicians may be encouraged to use PROMs as part of their routine clinical care. For example, innovative delivery methods using app or web-based based technology [for example, through data platforms such as REDCap- Research Electronic Data Capture (https://www.project-redcap.org/)] are helping to streamline data capture from patients by facilitating PROM completion on tablets, mobile phones and the internet.

Employing digital media also allows novel methods such as ecological momentary assessment (EMA)[64-68] to be used. EMA refers to a collection of methods often used in behavioural medicine research where a patient repeatedly reports on, for example, their symptoms or quality of life close in time to when they experience them and in their own environment[64]. EMA data can be collected in various ways, including written diaries, electronic diaries and telephone. EMA using mobile phones, for example, could facilitate the collection of PROM data in real-time and overcomes some of the inherent problems of PROMs, such as patient recall accuracy.

The burden of data collection associated with the routine collection of PROMs data in practice can be reduced by simplifying data collection using techniques such as computerised adaptive testing (CAT). CAT involves using a computer to administer a PROM, one question at a time. The CAT then uses an algorithm to choose the subsequent question based on the previous answer given. For example if a PROM is assessing hand function and in response to the first question a patient answers that their hand function is ‘normal’, then there is little to be gained from asking increasingly granular questions about hand problems, which may be more appropriate to someone who has ‘non-normal’ hand function. By pre-selecting questions, the PROM score can be determined without having to ask all of the questions[61,62,69,70].

Another future technology is that CAT and electronic PROMs could be administered by virtual assistants (such as Siri or Alexa, or similar) using voice recognition software to avoid the need for manual form filling to further reduce the manpower required for data collection[59-62].

The process of developing a new PROM is often a complex and resource-intensive process. If possible, researchers should first consider whether any existing PROMs could be suitable candidates for use, or if they could be adapted. This review provides a general introduction to PROMs and some background regarding the recent drive to collect PROM data. It then reports on findings from a scoping review that identified good practice and issues that should be considered prior to adapting existing PROMs. These issues are organised under the specific headings of: defining the requirements of a PROM, identifying and appraising existing tools, adapting existing PROMs, issues of content validity and getting the right people involved. The review ends with some insights into different psychometric methods, clinical use of PROMs and future PROMs developments.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: British Society of Gastroenterology.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gholamrezaei A, Australia; Gram-Hanssen A, Denmark S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gao CC

| 1. | Hutchings HA, Alrubaiy L. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Routine Clinical Care: The PROMise of a Better Future? Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1841-1843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. [cited 5 November 2019]. In: U.S. Food and Drug Administration [Internet]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. |

| 3. | Downing J, Namisango E, Harding R. Outcome measurement in paediatric palliative care: lessons from the past and future developments. Ann Palliat Med. 2018;7:S151-S163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Davidson M, Keating J. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): how should I interpret reports of measurement properties? Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:792-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | European Medicines Agency. Reflection paper on th regulatory guidance for the use of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQL) measures in the evaluation of medicinal products. [cited 5 November 2019]. In: European Medicines Agency [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-regulatory-guidance-use-healthrelated-quality-life-hrql-measures-evaluation_en.pdf. |

| 6. | Revicki DA; Regulatory Issues and Patient-Reported Outcomes Task Force for the International Society for Quality of Life Research. FDA draft guidance and health-outcomes research. Lancet. 2007;369:540-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Calvert M, Kyte D, Mercieca-Bebber R, Slade A, Chan AW, King MT; the SPIRIT-PRO Group, Hunn A, Bottomley A, Regnault A, Chan AW, Ells C, O'Connor D, Revicki D, Patrick D, Altman D, Basch E, Velikova G, Price G, Draper H, Blazeby J, Scott J, Coast J, Norquist J, Brown J, Haywood K, Johnson LL, Campbell L, Frank L, von Hildebrand M, Brundage M, Palmer M, Kluetz P, Stephens R, Golub RM, Mitchell S, Groves T. Guidelines for Inclusion of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Clinical Trial Protocols: The SPIRIT-PRO Extension. JAMA. 2018;319:483-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 554] [Article Influence: 79.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Porter ME, Larsson S, Lee TH. Standardizing Patient Outcomes Measurement. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:504-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 455] [Article Influence: 50.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ. 2013;346:f167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 971] [Cited by in RCA: 1269] [Article Influence: 105.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Devlin NJ, Appleby J. Getting the most out of PROMs. Putting health outcomes at the heart of NHS decision-making. London: The Kings Fund, 2010. |

| 11. | Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19-32. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. Cochrane Update. 'Scoping the scope' of a cochrane review. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33:147-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in RCA: 692] [Article Influence: 49.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, de Vet HCW, Terwee CB. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1147-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 937] [Cited by in RCA: 1935] [Article Influence: 276.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, et al COSMIN methodology for assessing the content validity of PROMs. User manual. Version 1.0. [cited 5 November 2019]. In: COSMIN [Internet]. Available from: https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-methodology-for-content-validity-user-manual-v1.pdf. |

| 15. | van der Wees PJ, Verkerk EW, Verbiest MEA, Zuidgeest M, Bakker C, Braspenning J, de Boer D, Terwee CB, Vajda I, Beurskens A, van Dulmen SA. Development of a framework with tools to support the selection and implementation of patient-reported outcome measures. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2019;3:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Luckett T, King MT. Choosing patient-reported outcome measures for cancer clinical research--practical principles and an algorithm to assist non-specialist researchers. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:3149-3157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bausewein C, Daveson BA, Currow DC, Downing J, Deliens L, Radbruch L, Defilippi K, Lopes Ferreira P, Costantini M, Harding R, Higginson IJ. EAPC White Paper on outcome measurement in palliative care: Improving practice, attaining outcomes and delivering quality services - Recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Task Force on Outcome Measurement. Palliat Med. 2016;30:6-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Francis DO, McPheeters ML, Noud M, Penson DF, Feurer ID. Checklist to operationalize measurement characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures. Syst Rev. 2016;5:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Greenhalgh J, Long AF, Brettle AJ, Grant MJ. Reviewing and selecting outcome measures for use in routine practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 1998;4:339-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | DeVellis RF. Classical test theory. Med Care. 2006;44:S50-S59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Snyder CF, Watson ME, Jackson JD, Cella D, Halyard MY; Mayo/FDA Patient-Reported Outcomes Consensus Meeting Group. Patient-reported outcome instrument selection: designing a measurement strategy. Value Health. 2007;10 Suppl 2:S76-S85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, Erikson P; ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8:94-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3263] [Cited by in RCA: 3289] [Article Influence: 164.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | World Health Organization. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. [cited 5 November 2019]. In: World Health Organization [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/. |

| 24. | Kuliś D, Bottomley A, Velikova G, Greimel E, Koller M; on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. EORTC Quality of Life Group Translation Procedure. [cited 5 November 2019]. In: EORTC Quality of Life Group Translation Procedure [Internet]. Available from: https://qol.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/translation_manual_2017.pdf. |

| 25. | Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3186-3191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6161] [Cited by in RCA: 7582] [Article Influence: 303.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Eremenco S, Pease S, Mann S, Berry P; PRO Consortium’s Process Subcommittee. Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Consortium translation process: consensus development of updated best practices. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;2:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Harachi TW, Choi Y, Abbott RD, Catalano RF, Bliesner SL. Examining equivalence of concepts and measures in diverse samples. Prev Sci. 2006;7:359-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Alrubaiy L, Hutchings HA, Williams JG. Assessing patient reported outcome measures: A practical guide for gastroenterologists. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2:463-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales. A practical guide to their development and use. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. |

| 30. | Wiering B, de Boer D, Delnoij D. Asking what matters: The relevance and use of patient-reported outcome measures that were developed without patient involvement. Health Expect. 2017;20:1330-1341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wiering B, de Boer D, Delnoij D. Patient involvement in the development of patient-reported outcome measures: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2017;20:11-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wiering B, de Boer D, Delnoij D. Patient involvement in the development of patient-reported outcome measures: The developers' perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, Amtmann D, Bode R, Buysse D, Choi S, Cook K, Devellis R, DeWalt D, Fries JF, Gershon R, Hahn EA, Lai JS, Pilkonis P, Revicki D, Rose M, Weinfurt K, Hays R; PROMIS Cooperative Group. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2547] [Cited by in RCA: 3704] [Article Influence: 246.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, Ring L. Content validity--establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1--eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14:967-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 630] [Cited by in RCA: 792] [Article Influence: 56.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, Abetz L, Arnould B, Bayliss M, Crawford B, Rosa K. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:1087-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Addario B, Geissler J, Horn MK, Krebs LU, Maskens D, Oliver K, Plate A, Schwartz E, Willmarth N. Including the patient voice in the development and implementation of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. Health Expect. 2020;23:41-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Butt Z, Reeve B. Enhancing the patient's voice: Standards in the deign and selection of patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) for use in patient-centred outcomes research. Methodology committee report: Patient centredness workshop, 2012. |

| 38. | Zibrowski E, Carr T, McDonald S, Thiessen H, van Dusen R, Goodridge D, Haver C, Marciniuk D, Stobart C, Verrall T, Groot G. A rapid realist review of patient engagement in patient-oriented research and health care system impacts: part one. Res Involv Engagem. 2021;7:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Maitland A, Presser S. How Accurately Do Different Evaluation Methods Predict the Reliability of Survey Questions? J Surv Stat Methodol. 2016;4:362-381. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 40. | Willis G. Analysis of the Cognitive Interview in Questionnaire Design. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. |

| 41. | Tourangeau R. Cognitive science and survey methods: a cognitive perspective. In: Jabine T, Straf M, Tanur J, Tourangeau R. Cognitive Aspects of Survey Design: Building a Bridge Between the Disciplines. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1984: 73-100. |

| 42. | Moores KL, Jones GL, Radley SC. Development of an instrument to measure face validity, feasibility and utility of patient questionnaire use during health care: the QQ-10. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24:517-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Res Nurs Health. 2007;30:459-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1658] [Cited by in RCA: 2413] [Article Influence: 134.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Streiner DL. A checklist for evaluating the usefulness of rating scales. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38:140-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Petrillo J, Cano SJ, McLeod LD, Coon CD. Using classical test theory, item response theory, and Rasch measurement theory to evaluate patient-reported outcome measures: a comparison of worked examples. Value Health. 2015;18:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Hobart J, Cano S. Improving the evaluation of therapeutic interventions in multiple sclerosis: the role of new psychometric methods. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:iii, ix-ix, 1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Cano SJ, Hobart JC. The problem with health measurement. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:279-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Hays RD, Morales LS, Reise SP. Item response theory and health outcomes measurement in the 21st century. Med Care. 2000;38:II28-II42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Pusic AL, Lemaine V, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Cano SJ. Patient-reported outcome measures in plastic surgery: use and interpretation in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:1361-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Vanhoutte EK, Hermans MC, Faber CG, Gorson KC, Merkies IS, Thonnard JL; PeriNomS Study Group. Rasch-ionale for neurologists. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2015;20:260-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Cappelleri JC, Jason Lundy J, Hays RD. Overview of classical test theory and item response theory for the quantitative assessment of items in developing patient-reported outcomes measures. Clin Ther. 2014;36:648-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD, Granger CV, Hamilton BB. The structure and stability of the Functional Independence Measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:127-132. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Pakhomov SV, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, Roger VL. Agreement between patient-reported symptoms and their documentation in the medical record. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:530-539. [PubMed] |

| 54. | The Kings Fund. From vision to action: making patient-centred care a reality. [cited 5 November 2019]. In: The Kings Fund [Internet]. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/vision-action-making-patient-centred-care-reality. |

| 55. | Nelson EC, Eftimovska E, Lind C, Hager A, Wasson JH, Lindblad S. Patient reported outcome measures in practice. BMJ. 2015;350:g7818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 47.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Anatchkova M, Donelson SM, Skalicky AM, McHorney CA, Jagun D, Whiteley J. Exploring the implementation of patient-reported outcome measures in cancer care: need for more real-world evidence results in the peer reviewed literature. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2018;2:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Wintner LM, Sztankay M, Aaronson N, Bottomley A, Giesinger JM, Groenvold M, Petersen MA, van de Poll-Franse L, Velikova G, Verdonck-de Leeuw I, Holzner B; EORTC Quality of Life Group. The use of EORTC measures in daily clinical practice-A synopsis of a newly developed manual. Eur J Cancer. 2016;68:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | D'Amico E, Haase R, Ziemssen T. Review: Patient-reported outcomes in multiple sclerosis care. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;33:61-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Øvretveit J, Zubkoff L, Nelson EC, Frampton S, Knudsen JL, Zimlichman E. Using patient-reported outcome measurement to improve patient care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29:874-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Calvert MJ, O'Connor DJ, Basch EM. Harnessing the patient voice in real-world evidence: the essential role of patient-reported outcomes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:731-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Dobbs TD, Rodrigues J, Hart AM, Whitaker IS. Improving measurement 1: Harnessing the PROMise of outcome measures. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2019;72:363-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Moskowitz DS, Young SN. Ecological momentary assessment: what it is and why it is a method of the future in clinical psychopharmacology. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31:13-20. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Upchurch Sweeney CR. Ecological Momentary Assessment. In: Gellman MD, Turner JR. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. New York, NY: Springer, 2013. |

| 64. | Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2845] [Cited by in RCA: 3483] [Article Influence: 204.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Valderas JM, Ferrer M, Mendívil J, Garin O, Rajmil L, Herdman M, Alonso J; Scientific Committee on "Patient-Reported Outcomes" of the IRYSS Network. Development of EMPRO: a tool for the standardized assessment of patient-reported outcome measures. Value Health. 2008;11:700-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | McDowell I, Jenkinson C. Development standards for health measures. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1996;1:238-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Bombardier C, Tugwell P. Methodological considerations in functional assessment. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1987;14 Suppl 15:6-10. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5565] [Cited by in RCA: 7307] [Article Influence: 384.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Jensen RE, Snyder CF, Basch E, Frank L, Wu AW. All together now: findings from a PCORI workshop to align patient-reported outcomes in the electronic health record. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5:561-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Acaster S, Cimms T, Lloyd A. The design and selection of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for use in patient centred outcomes research. [cited for-Use-in-Patient-Centered-Outcomes-Research1.pdf (date of access]. In: Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute [Internet]. Available from: https://www.pcori.org/assets/The-Design-and-Selection-of-Patient-Reported-Outcomes-Measures-for-Use-in-Patient-Centered-Outcomes-Research1.pdf. |