Published online Jan 27, 2022. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v14.i1.274

Peer-review started: March 17, 2021

First decision: May 2, 2021

Revised: June 8, 2021

Accepted: December 28, 2021

Article in press: December 28, 2021

Published online: January 27, 2022

Processing time: 309 Days and 17.2 Hours

In December 2019, the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) emerged and rapidly spread worldwide, becoming a global health threat and having a tremendous impact on the quality of life (QOL) of individuals.

To evaluate the awareness of patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) regarding the COVID-19 emergency and how it impacted on their QOL.

Patients with an established diagnosis of CLD (cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis) who had been evaluated at our Outpatient Liver Disease Clinic during the 6-mo period preceding the start of Italian lockdown (March 8, 2020) were enrolled. Participants were asked to complete a two-part questionnaire, administered by telephone according to governmental restrictions: The first section assessed patients’ basic knowledge regarding COVID-19, and the second evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 emergency on their QOL. We used the Italian version of the CLD questionnaire (CLDQ-I). With the aim of evaluating possible changes in the QOL items addressed, the questionnaire was administered to patients at the time of telephone contact with the specific request to recall their QOL perceptions during two different time points. In detail, patients were asked to recall these perceptions first during time 0 (t0), a period comprising the 2 wk preceding the date of ministerial lockdown decree (from February 23 to March 7, 2020); then, in the course of the same phone call, they were asked to recall the same items as experienced throughout time 1 (t1), the second predetermined time frame encompassing the 2 wk (from April 6 to April 19) preceding our telephone contact and questionnaire administration. All data are expressed as number (%), and continuous variables are reported as the median (interquartile range). The data were compared using the Wilcoxon paired non-parametric test.

A total of 111 patients were enrolled, of whom 81 completed the questionnaire. Forty-nine had liver cirrhosis, and all of them had compensated disease; 32 patients had autoimmune liver disease. The majority (93.8%) of patients were aware of COVID-19 transmission modalities and on how to recognize the most common alarm symptoms (93.8%). Five of 32 (15.6%) patients with autoimmune liver disease reported having had the need to receive more information about the way to manage their liver disease therapy during lockdown and nine (28.2%) thought about modifying their therapy without consulting their liver disease specialist. About the impact on QOL, all CLDQ-I total scores were significantly worsened during time t1 as compared to time t0.

The COVID-19 epidemic has had a significant impact on the QOL of our population of patients, despite a good knowledge of preventive measure and means of virus transmission.

Core Tip: Although negative mental health outcomes in the Italian general population during coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) lockdown have already been reported, our study was among one of the first investigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with chronic liver disease and addressing the subpopulation of patients with autoimmune chronic hepatitis.

- Citation: Zannella A, Fanella S, Marignani M, Begini P. COVID-19 emergency: Changes in quality of life perception in patients with chronic liver disease-An Italian single-centre study. World J Hepatol 2022; 14(1): 274-286

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v14/i1/274.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i1.274

The World Health Organization defines health as "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity"[1]: This is the multidimensional target which healthcare professionals pursue. The coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic strongly impacted on this definition at many levels, affecting both health and psychological well-being[1]. In Italy, in response to this worldwide emergency, measures were enforced, aimed at the reduction of inappropriate access to healthcare centres, which were considered as environments at a potential risk of crowding and viral infection spread. Outpatient visits were thus limited to emergencies or to supply life-saving medications, considering that even if all individuals are susceptible to COVID-19, those with underlying conditions, such as patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) or reduced immune functions, have been recognized to be at an increased risk to experience a more severe disease course and increased mortality rates[2].

As a result, all patients affected by CLD experienced a substantial change in their usual routine care. As emerged from the survey by the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver[3], the reorganization of the health-care system, which followed the pandemic phase, has severely affected the management of liver diseases in Italy.

It is well known from previous studies that patients suffering from CLD, especially cirrhosis, have been shown to experience a significantly impaired health related quality of life (HRQOL) when compared to patients without liver disease[4]. These issues encompass mental impairment and determine limitations which affect patients’ ability to perform normal daily activities. Collecting information on HRQOL has been shown to be helpful in assessing the multidimensional impact of liver disease on patients’ well-being. The issue of quality of life (QOL) among patients with chronic diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the subject of clinical studies in different countries and clinical settings. During the pandemic and because of it, the presence of a chronic health problem has generally been shown to represent per se a risk factor for a worsening in the QOL. In a study from Singapore, analyzing QOL among patients with cardiovascular disease, a significant worsening of mental health related issues was described[5]. In another study from Poland, conducted among stage III and IV oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy, a questionnaire was administered including questions about QOL during the COVID-19 pandemic: The study showed a significant reduction in cognitive (P < 0.0001) and social (P < 0.0001) functioning, as well as worsening of symptoms such as fatigue, insomnia, and appetite[6]. In the study by Falcone et al[7] patients with thyroid cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic followed in a single endocrine cancer centre in Italy received two questionnaires to evaluate changes in QOL. Some patients were contacted by phone and answered questions during a single call. Others, instead, had access to the questionnaires by links provided by mail. The research team produced ex novo the first questionnaire, which was developed ad hoc to explore and measure the emotional impact of the rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic given the absence in the literature of a similar instrument, while the second questionnaire was a validated Italian translation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire. In that study, HRQOL appeared to be affected by the COVID-19 pandemic among this cohort of patients, regardless of their disease severity or current health-care needs[7]. Nevertheless, diverging results have been described among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), both by Azzam et al[8] and Algahtani et al[9] in two different studies from Saudi Arabia. In the latter, as explored and analyzed by means of a questionnaire submitted through various online communication channels including email, organizational portals, and social media platforms (WhatsApp, Twitter, and Facebook), HRQOL appeared to be unaffected by the COVID-19 pandemic. In that study, evaluating HRQOL among patients with IBD pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic using the IBD-disk questionnaire in a Saudi Arabia tertiary care IBD centre, HRQOL appeared to be unaffected by the COVID-19 pandemic among this cohort of patients. These results suggest that different diseases, patients’ samples, and investigative methods adopted might account for the diverging results observed in these latter IBD studies.

Given the scarcity of HRQOL data among patients with CLD during the COVID-19 pandemic, the present study aimed to assess patients’ grade of awareness about the current global emergency, and how this event impacted on their interaction with the healthcare system and planned follow-up programmes. We also explored patients’ grade of awareness about the COVID-19 emergency, assessing the effect of mandatory social limitations on their QOL.

All outpatients with an established diagnosis of CLD [cirrhosis and autoimmune liver diseases (ALD), i.e. autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis], ≥ 18 years of age, who had been attending our hepatology outpatient clinic (Sant’Andrea University Hospital, “Sapienza” University of Rome) during the 6 mo prior to introduction of the social lockdown strategies (March 8, 2020) were enrolled in this study. As part of the suggested telemedicine clinical approach, and in order to maintain contact with our CLD patients, we asked participants to complete a questionnaire on their awareness regarding the COVID-19 emergency, and how it had impacted on their QOL. Patients with either language or cognitive difficulties, and those unable to understand or complete the questionnaire were excluded. Considering the mandatory action of government-imposed lockdown strategy[10], and that the healthcare strategy of our department was switched from face-to-face to telehealth as requested by our Hospital upon Regional order, the questionnaire was completed by means of telephonic interviews.

The study was conducted according to Sant’Andrea Hospital directives following Latium Region order (No. 3405/2020 and 4888/2020, Regione.Lazio.Ufficiale UO54467/U0218196, 11/03/2020). All patients included in the study had already provided written consent to the use of their clinical data for research purposes at the time of their first hospital visit; verbal consent was also obtained at the beginning of the telephone interview. Patients were carefully informed about the purpose of our survey, and given the option to opt-out in case of refusal. We collected clinical information regarding age and aetiology of liver disease. The Child-Pugh score was calculated for each patient with liver cirrhosis based on laboratory tests no older than 3 mo.

The study protocol complied with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (6th revision, 2008), and was approved by our institution's human research committee.

A two-part questionnaire was used, and is fully available in Table 1.

| Questions |

| First part |

| 1 Are you aware that the novel coronavirus is transmitted to people? |

| 2 Are you aware that symptoms including fever, cough, and breathing difficulties are signs of alarm? |

| 3 Are you aware that people with chronic liver disease are at higher risk of developing a severe form of the disease? |

| 4 Are you aware that when you go out, you always have to use personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves? |

| 5 Do you always respect prevention and protection measures such as social distancing? |

| 6 Do you use adequate hygiene measures such as frequently washing your hands? |

| 7 During this period, did you need to contact your general physician for your liver disease? |

| 8 If you answered yes, did you have difficulty in contacting him/her? |

| 9 During this period, did you need to contact a gastroenterologist specialist for your liver disease? |

| 10 If you answered yes, did you have difficulty in contacting him/her? |

| 11 Have you received more detailed information about the management of your therapy? |

| 12 Do you know that immunosuppressed patients are more at risk of getting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection? |

| 13 Have you thought about modifying your immunosuppressive therapy on your own? |

| 14 Did you manage to perform the six-month follow-up ultrasound for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance? |

| Second part |

| 1 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you been troubled by a feeling of abdominal bloating? |

| 2 How much of the time have you been tired or fatigued during the last two weeks? |

| 3 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you experienced bodily pain? |

| 4 How often during the last two weeks have you felt sleepy during the day? |

| 5 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you experienced abdominal pain? |

| 6 How much of the time during the last two weeks has shortness of breath been a problem for you in your daily activities? |

| 7 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you not been able to eat as much as you would like? |

| 8 How much of the time in the last two weeks have you been bothered by having decreased strength? |

| 9 How often during the last two weeks have you had trouble lifting or carrying heavy objects? |

| 10 How often during the last two weeks have you felt anxious? |

| 11 How often during the last two weeks have you felt a decreased level of energy? |

| 12 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you felt unhappy? |

| 13 How often during the last two weeks have you felt drowsy? |

| 14 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you been bothered by a limitation of your diet? |

| 15 How often during the last two weeks have you been irritable? |

| 16 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you had difficulty sleeping at night? |

| 17 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you been troubled by a feeling of abdominal discomfort? |

| 18 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you been worried about the impact your liver disease has on your family? |

| 19 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you had mood swings? |

| 20 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you been unable to fall asleep at night? |

| 21 How often during the last two weeks have you had muscle cramps? |

| 22 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you been worried that your symptoms will develop into major problems? |

| 23 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you had a dry mouth? |

| 24 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you felt depressed? |

| 25 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you been worried about your condition getting worse? |

| 26 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you had problems concentrating? |

| 27 How much of the time have you been troubled by itching during the last two weeks? |

| 28 How much of the time during the last two weeks have you been worried about never feeling any better? |

The first part was specifically developed by our liver team and aimed to: (1) Investigate patients’ awareness about the COVID-19 emergency and explore how this event had impacted on their contact with the healthcare system and their planned hepatological follow-up programmes; (2) Investigate whether patients had used personal protective equipment (PPE) (i.e. surgical masks and gloves), and applied preventive/protection measures such as social distancing and adequate hygiene strategies (e.g. frequent hand washing), as indicated by the Italian Government following the advice of the Italian National Institute of Health; (3) Assess the basic knowledge of COVID-19, including its means of transmission, patients’ capacity to recognize alarm symptoms, and awareness of being at higher risk to develop a more severe clinical form since affected by liver disease; and (4) Explore whether patients had encountered difficulties in contacting their general physician and/or their liver diseases specialist. Adherence to the performance of liver ultrasound testing scheduled during the study period was also assessed among patients with either liver cirrhosis or advanced liver fibrosis. Three questions (Q) of this first section of the questionnaire (Q11 to 13) were addressed only to patients with ALD, in particular to investigate if, during the lockdown period, they had thought of independently modifying their therapy.

As suggested in the recent publication by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, regarding the development of questionnaires to be used as instruments to investigate the impact of COVID-19 pandemic, even if in different settings, the questionnaire was designed to be easily conducted in the same manner each time[11].

We have thus formulated closed-ended questions to make answering easier. We developed simple and clear questions in order to avoid misunderstandings, and asked the simplest questions initially and the most difficult at the end, so that the interviewees could feel more comfortable.

The response to each question was scored as either positive (yes) or negative (no).

This section was pre-tested and validated on a smaller-scale target group of 25 inpatients [15 (60.0%) men, mean age 64 years], affected by CLD and admitted to our hospital ward during March 2020, to verify its full comprehensibility and practical applicability as a tool to be administered over the phone. The results obtained in this test group were not included in the final analysis.

The second section was aimed at evaluating the impact of the COVID-19 emergency on the QOL of study patients, using the Italian version of the CLD questionnaire (CLDQ-I)[12]. With the aim of evaluating possible changes in the QOL items addressed, the questionnaire was administered to patients at the time of telephone contact with the specific request to recall their QOL perceptions during two different time periods. In detail, patients were asked to recall these perceptions first during time 0 (t0), a period comprising the 2 wk preceding the date of ministerial lockdown decree (from February 23 to March 7, 2020); then, in the course of the same phone call, they were asked to recall the same items as experienced throughout time 1 (t1), the second predetermined time frame encompassing the 2 wk (from April 6 to April 19) preceding our telephone contact and questionnaire administration. We formulated a total score that included each question regarding the same domain of interest for time t0 and time t1.

Total scores are summarized as main text tables. Data summarizing single scores regarding each item of all single domains are presented as tables in the supplementary data section (Supplementary Tables 1-12).

All data are expressed as number (%), and continuous variables are reported as the median ± interquartile range (IR). The data were compared using the Wilcoxon paired non-parametric test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data analyses was reviewed by our biomedical statistician. Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc Statistical Software version 19.0.4.

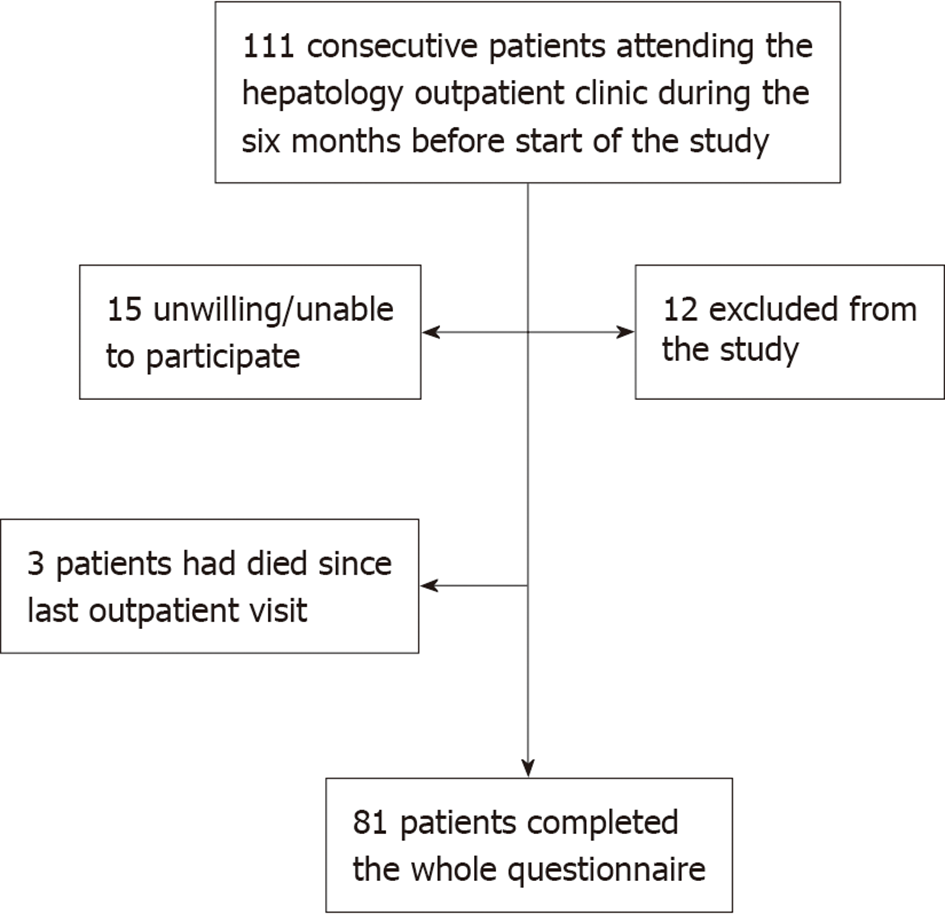

One hundred and eleven [54 males (48.6%) and 57 females (51.4%), average age 66.5 years] consecutive patients affected by CLD fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Out of these, 81 (73%) finally participated in the study as shown in the flowchart (Figure 1), and were equally distributed by gender [43 males (53%) and 38 females (47%); mean age was 65.6 ± 11.8 years]. Forty-nine (60.5%) patients had liver cirrhosis, and all of them had compensated disease (≤ 7). Thirty-two (39.5%) patients had ALD; of them, 13 had autoimmune hepatitis, 17 primary biliary cholangitis, and two primary sclerosing cholangitis. In the population with ALD, eight had liver cirrhosis. Clinical characteristics of the study patients are summarized in Table 2.

| Variable | n = 81 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 38 (47) |

| Female | 43 (53) |

| Aetiology, n (%) | |

| Cirrhosis | 49 |

| HBV | 7 (8.6) |

| HCV | 22 (27.2) |

| Cirrhosis Alcoholic-related | 9 (11.1) |

| Cirrhosis HBV + alcoholic-related | 1 (1.2) |

| Cirrhosis HCV + alcoholic-related | 1 (1.2) |

| Cirrhosis Metabolic-related | 9 (11.1) |

| AIH | 8 (9.9) |

| Cirrhosis AIH-related | 5 (6.2) |

| PBC | 14 (17.3) |

| Cirrhosis PBC-related | 3 (3.7) |

| PSC | 2 (2.5) |

| Child-Pugh score, n (%) | |

| A5 | 46 (80.7) |

| A6 | 6 (10.5) |

| B7 | 5 (8.8) |

Most of the patients (76/81 93.8%) reported being aware of both COVID-19 transmission modalities (Q1), and of its most common alarm symptoms (76/81 93.8%) (Q2).

Twelve (15%) of the 81 patients reported feeling the need to contact their family physicians during lockdown, and 11 of them (11/12, 91.6%) encountered difficulties in reaching them (Q7-8). The majority of these patients (10/12, 83%) had liver cirrhosis.

Questions 11, 12, and 13 were only addressed to the 32 patients with ALD, as they focused specifically on the impact of the infection among these patients. Examining the responses to Q11 to 13, asked only to the 32 patients with ALD, we observed that five (15.6%) of them reported having had the need to receive more information on how to manage their liver disease therapy during lockdown (Q11), and nine (28.2%) thought about modifying their therapy without consulting their liver disease specialist.

Finally, regarding the last question (Q14), out of 57 patients with liver cirrhosis, 49 (49/57, 85.9%) had a follow-up liver ultrasound scheduled for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance during the lockdown period; although most of them (29/49, 60%) were able to perform it, adhering to the scheduled timing, 40% (20/49) could not. The complete panel of questions and relative answers are summarized in Table 3.

| Questions | Patients’ answer “YES” number (%) | Patients’ answer “NO” number (%) |

| 1 Are you aware that the novel coronavirus is transmitted to people? | 76 (93.8) | 5 (6.2) |

| 2 Are you aware that symptoms including fever, cough, and breathing difficulties are signs of alarm? | 76 (93.8) | 5 (6.2) |

| 3 Are you aware that people with chronic liver disease are at higher risk of developing a severe form of the disease? | 69 (85) | 12 (15) |

| 4 Are you aware that when you go out, you always have to use personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves? | 77 (95) | 4 (5) |

| 5 Do you always respect prevention and protection measures such as social distancing? | 60 (74) | 21 (26) |

| 6 Do you use adequate hygiene measures such as frequently washing your hands? | 60 (74) | 21 (26) |

| 7 During this period, did you need to contact your general physician for your liver disease? | 12 (15%) | 69 (85) |

| 8 If you answered yes, did you have difficulty in contacting him/her? | 11 (91.7)1 | 1 (8.3) |

| 9 During this period, did you need to contact a Gastroenterologist specialist for your liver disease? | 12 (15%) | 69 (85) |

| 10 If you answered yes, did you have difficulty in contacting him/her? | 8 (67%)2 | 4 (33.3) |

| 11 Have you received more detailed information about the management of your therapy? | 5 (15.6) | 27 (84.4) |

| 12 Do you know that immunosuppressed patients are more at risk of getting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-infection? | 29 (90.6%) | 3 (9.4%) |

| 13 Have you thought about modifying your immunosuppressive therapy on your own? | 9 (28.2%) | 23 (71.8%) |

| 14 Did you manage to perform the six-month follow-up ultrasound for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance? | 29 (60%)3 | 20 (40%) |

All the 81 patients completing the first part of the questionnaire also fully completed the following CLDQ section. First, we collected the data of all patients enrolled. Patients with autoimmune CLD were then examined as a subgroup.

In each group, all CLDQ-I total scores were significantly worsened during time t1 as compared to time t0. Global data for all patients enrolled and for those with ALD are summarized and expressed as total scores in Tables 4 and 5.

| Items | Median, t0 | Range interquartile, t0 | Median, t1 | Range interquartile, t1 | P value |

| Abdominal symptoms: 1, 5, 17 | 1 | 1-2 | 1 | 1-2 | aP < 0.0001 |

| Fatigue: 2, 4, 8, 11, 13 | 2 | 1-2 | 2 | 1-2 | bP < 0.0001 |

| Systemic symptoms: 3, 6, 21, 23, 27 | 1 | 1-2 | 1 | 1-2 | cP < 0.0001 |

| Activity: 7, 9, 14 | 2 | 1-5 | 3 | 1-5 | dP = 0.0245 |

| Emotional function: 10, 12, 15, 16, 19, 20, 24, 26 | 2 | 1-2 | 2 | 1-3 | eP < 0.0001 |

| Worry: 18, 22, 25, 28 | 2 | 1-2 | 2 | 1-3 | fP < 0.0001 |

| Items | Median t0 | Range interquartile t0 | Median t1 | Range interquartile t1 | P value |

| Abdominal symptoms: 1, 5, 17 | 1 | 1-1 | 1 | 1-2 | aP = 0.0045 |

| Fatigue: 2, 4, 8, 11, 13 | 1 | 1-2 | 1 | 1-2 | bP < 0.0001 |

| Systemic symptoms: 3, 6, 21, 23, 27 | 1 | 1-2 | 1 | 1-2 | cP < 0.0004 |

| Activity: 7, 9, 14 | 2 | 1-5 | 2 | 1-5 | dP = 0.0938 |

| Emotional function: 10, 12, 15, 16, 19, 20, 24, 26 | 1 | 1-2 | 2 | 1-3 | eP < 0.0001 |

| Worry: 18, 22, 25, 28 | 1 | 1-2 | 2 | 1-3 | fP < 0.0001 |

Significant worsening in all answers regarding abdominal symptoms and systemic symptoms between the two-time frames (P < 0.0001; P < 0.0001) was observed (Table 4).

The second domain assessed perception of fatigue and total score regarding these questions, and a significant worsening was noted (P < 0.0001) (Table 4).

The fifth domain evaluated emotional function (total score, Table 4).

To provide a deeper insight on this latter domain, we listed single scores of each item composing it (single scores, Supplementary Table 5).

In detail, when observing single scores, a significant worsening of anxiety (P < 0.0001), and an increased perception of irritability (P < 0.0001) and depression (P < 0.0001) were detected. Mood swings were also significantly frequent (P < 0.0001), as well as the tendency to feel unhappy (P = 0.0066), and the difficulties in sleeping (P = 0.0002) and in falling asleep at night (P = 0.0001). The ability to concentrate was also perceived as being worsened (P = 0.0010) (Supplementary Table 5).

The sixth and last domains analysed the state of worry (total score, Table 4).

The items in this section identified a significant increase in worries about the impact of their liver disease on their family (P ≤ 0.0001) and a worsening of their symptoms (P < 0.0001).

The results also showed an increase in the time spent thinking about the possibility of a worsening of their condition (P < 0.0001) or of never getting better again (P = 0.0008) (Supplementary Table 6). Dataset analyzed in this study is included in the Supplementary Table 6.

Findings among patients with ALD differed minimally from those observed in the non-autoimmune group. In the former group, a worsening of total score regarding abdominal (P = 0.0045) and systemic symptoms (P < 0.0004) was observed (total score, Table 5).

In detail, perception of shortness of breath, itching, and the tendency to feel unhappy, which significantly increased during the second time period in the non-ALD group (P = 0.0004, 0.0259, and 0.0027, respectively), did not differ in the ALD subgroup (P = 0.7695, 0.0840, and 0.3054, respectively), suggesting, however, a role of sample size in determining such numeric differences.

Data regarding the autoimmune subgroup are available in the Supplementary Tables 7-12.

Although negative mental health outcomes in the Italian general population during COVID-19 lockdown have already been reported[13,14], our study is original since it investigated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with CLD, in addition addressing the subpopulation of patients with ALD.

The presence of CLD and cirrhosis, with the latter being a condition acknowledged to be associated with immune deregulation[15], have been proven to be significant comorbidities, identifying these liver disease patients as running an increased risk of more severe outcomes and complications in case of COVID-19[2,16]. A recent meta-analysis, published by Kovalic et al[17], showed that patients with CLD do not have an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 but, in case of infection, are more likely to experience a severe/critical COVID-19 related disease, with mortality rates higher than those without CLD.

Probably due to the capillary spread of information (media broadcast via television, internet, newspaper, etc.), and to the enforcement of government measures aimed at controlling spread of the pandemic, we observed that most of the patients evaluated in our study were aware of the main routes and means of transmission and of the most relevant alarm symptoms of COVID-19. The patients reported to correctly apply PPE, respect social distancing, and frequently wash their hands, in compliance with the governmental recommendations. Furthermore, it should be noted that most of the patients were aware of an increased risk of developing a more severe clinical form of COVID-19, because of their liver diseases. Our observation confirms how a correct and responsible communication campaign is able to effectively reach special populations including patients with specific medical problems, and to increase their awareness of the risks of emergent and unpredictable situations such as a pandemic, fostering the adoption of appropriate preventive strategies and promoting infection containment.

With regard to contacts with the health-care system, the rapid spread of the pandemic has posed critical challenges for public health, research, and medical communities[10]. Since the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, outpatient visits were reduced to avoid nosocomial contact and limit contaminations. Government agencies and scientific societies[3] supported a general indication to manage patients remotely, in particular for patients with CLD and cirrhosis, even if available resources at the beginning of the pandemic were not prepared for this switch. A telemedicine approach was adopted where feasible, contacting patients by phone. However, this approach is clearly incapable of reaching all patients in need of assistance, as suggested by the not negligible rate of patients (27%) unwilling/unable to participate in our alternative clinical contact. Nevertheless, among those who participated in the study, we observed how the pandemic had a significant impact on their daily activities and feelings and in particular on their scheduled face-to-face clinical controls. This observation is even more relevant when considering patients with autoimmune diseases. Indeed, only less than 1/3 of our patients with ALD (28%) had thought of modifying their treatment on their own. Therefore, most patients acted according to the indications provided by major immunology and liver disease scientific societies[3,18] which suggest maintaining treatments, fearing reactivation more than immunosuppression, especially in a historical period in which exacerbations had to be absolutely avoided in order to limit access to hospital facilities[2].

It is, however, to be underlined that, regarding overall adherence to treatment among patients with ALD, studies indicate that these patients usually display an overall adherence of 80% or more to prescribed medications[19,20]. Nevertheless, these studies also show how altered/depressed mood might interfere with adherence to medical treatments. Sockalingam et al[20] noted that in patients with ALD, overall treatment adherence was more than 80%, and that subjects with greater adherence were the less anxious and depressed. Accordingly, a recent review indicates that the co-presence of anxiety or depression, regardless of the stage of liver disease, significantly reduces QOL and may be associated with non-adherence to prescribed therapy regimens among patents with ALD[21]. Thus, early recognition of "more fragile" patients might increase adherence to treatments, and in the context of a policy aimed at maintaining and boosting physician-patient relationship, telemedicine contact in times of social distancing might help reaching out and support uncertain patients in making the correct decisions[22]. Their specialists should reassure patients during these difficult social health emergencies to maintain a solid and realistic vision of their disease in order to avoid developing altered perceptions of its potential consequences, and dangerous drifts such as those regarding chronic medical treatments. It can be thus speculated that providing continuous contact with the patients, even with a limited telephone approach, would help them maintain a better QOL and correctly follow medical prescriptions.

The difficulties in contacting the liver specialist, and to attend the biannual follow-up abdominal ultrasound, were a clear example of how the lockdown strategies impacted on the routine clinical follow-up programme of these patients. For instance, a possible impact on the future percentages of delayed incident HCC diagnoses might be predicted, considering the observed 40% of missed follow-up ultrasound testings.

Even more relevant, our study underlines how most of the participants have had negative mental health-related lifestyle changes. This suggests that the sudden and unforeseen availability of void time resulted in patients having more time to think about their diseases and related consequences, a negative subject with psychological consequences further magnified by social isolation and causing an inevitable increase in terms of generalized concern. This hypothesis is supported by the data resulting from the evaluation of patients’ emotional status, in which the specific items show how the state of anxiety worsened, along with the perception of a more frequent sensation of irritability and depression. Significant was also the patients’ heightened concern about the impact that their liver disease could have on their familial relationships and the increased time spent in thinking about a worsening of their health condition and the possibility of not getting better.

It is also interesting to note that these significant changes were observed in a population that was proven to be aware of the emergency and correctly informed on how to cope with it. This suggests that informative campaigns should not only aim at providing up-to-date information, but should also be integrated by conveying positive messages when possible. Younossi et al[4] observed that decompensated cirrhosis was associated with a variety of symptoms that impact profoundly and negatively on their HRQL. Our cohort of patients with CLD, in addition to non-cirrhotics, included only patients with compensated liver cirrhosis (CHILD A-B7), a condition in which disease has a limited impact on QOL. Therefore, our data suggests that the differences in QOL observed through this study are more likely to be a consequence of the radical social changes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, rather than a worsening of the liver disease status.

We acknowledge that the small number of patients enrolled and the potential suggestion effect of our questionnaire in the format that we have adopted might represent a limitation of our study. We were aware of potential suggestion effect of this part of the questionnaire as it was formulated; however, considering the peculiar and at times awkward modality of contact (telephone call) for which it was developed, which demands for a short, simple, and clear questions and answers format, grouped by category, we decided to opt for this potentially criticisable but straightforward and explicit format. Nevertheless, the novelty constituted by a global viral pandemic find researchers with limited dedicated instruments to study the event, thus we believe that these potential limitations are to be considered as an expected element of the studies addressing QOL.

In conclusion, the rapid outbreak of the pandemic worldwide has had a significant, worsening impact on the QOL of patients with CLD, especially on those psychological areas involving states of worry/concern, sadness, and anxiety. The slight, at times marginally statistically significant, differences in the QOL questionnaire observed in the ALD and non-ALD groups should be interpreted considering the small sample size of the former group, globally suggesting an overall similar effect of lockdown on the general well-being of the two subgroups.

Even if our experience is limited to patients with compensated liver cirrhosis and ALD managed on our outpatient’s service, we believe that the utmost observation emerging from our study is the importance of maintaining a contact with patients, guaranteeing them a continuity of care. The spread of telemedicine with video call, telephone, e-mail, fax made it possible to maintain a contact with them without the risk of infectious exposure inherent to the face-to face approach. This novel approach to patient-physician contact, as recommended by the Italian Society of Hepatology, has to be institutionalized by the hospital; however, ad hoc reimbursement codes are to be developed as well as dedicated booking agendas. This method can replace a face-to-face visit in many hepatological conditions such as compensated cirrhosis or in patients with ALD who have reached durable medical control of their disease, since in a scenario of substantial clinical stability, it is not necessary to carry out a physical examination of the patient but only to collect, even indirectly, clinical-laboratory parameters easily communicated by the patient himself. For patients with a more severe disease, or during the course of HCC follow-up, especially if a liver lesion is detected, we opted for a face-to face approach considering it to be remain the preferred follow-up modality; however, reorganization of resources favoring remote clinical evaluations over face-to-face visits in stable patients, helped in reallocating clinical resources and allowed for the identification of dedicated time slots and spaces to perform ultrasound and HCC follow-up visits. It would also be desirable to integrate general practitioners in this novel, telemedicine-based, patient-physician network.

Even if the results of this study might not be exhaustive, due to the small number of patients tested and the limited set of issues evaluated, they provide relevant insights and raise several issues that deserve to be expanded in future studies. Reaching out to patients and investing time in listening to their health concerns will contribute to limiting and containing the state of anxiety related to their liver diseases. This will also probably contribute to the optimization of healthcare resources, reducing unnecessary accesses to emergency departments, and the related risk of infection exposure.

In December 2019, the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) emerged and rapidly spread worldwide, becoming a global health threat and having a tremendous impact on the quality of life (QOL) of individuals. In Italy, measures were enforced aimed at the reduction of inappropriate access to healthcare centres, which were considered as environments at a potential risk of crowding and viral infection spread.

All patients affected by chronic liver disease (CLD) experienced a substantial change in their usual routine care. As emerged from the survey by the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver, the reorganization of the health-care system, which followed the pandemic phase, has severely affected the management of liver diseases in Italy.

We wanted to evaluate the awareness of patients with CLD regarding the COVID-19 emergency and how it impacted on their QOL, and on their interaction with the healthcare system and planned follow-up programmes. Furthermore, we assessed whether for patients with autoimmune liver diseases the lack of contact with the specialist weighed on the management of their therapy.

Participants were asked to complete a two-part questionnaire, administered by telephone according to governmental restrictions: The first section assessed patients’ basic knowledge regarding COVID-19; the second evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 emergency on their QOL. We used the Italian version of the CLD questionnaire (CLDQ-I). With the aim of evaluating possible changes in the QOL items addressed, the questionnaire was administered to patients at the time of telephone contact with the specific request to recall their QOL perceptions during two different time periods.

The majority (93.8%) of patients were aware of COVID-19 transmission modalities and on how to recognize the most common alarm symptoms (93.8%). Five (15.6%) of 32 patients with autoimmune liver disease reported having had the need to receive more information about the way to manage their liver disease therapy during lockdown and nine (28.2%) thought about modifying their therapy without consulting their liver disease specialist. About the impact on QOL, all CLDQ-I total scores were significantly worsened during time t1 as compared to time t0.

The rapid outbreak of the pandemic worldwide has had a significant, worsening impact on the QOL of patients with CLD, especially on those psychological areas involving states of worry/concern, sadness, and anxiety. We believe that the utmost observation emerging from of our study is the importance of maintaining a contact with patients, guaranteeing them a continuity of care. The spread of telemedicine with video call, telephone, e-mail, and fax made it possible to maintain a contact with them without the risk of infectious exposure inherent to the face-to-face approach.

The telemedicine has to be institutionalized by the hospital; however, ad hoc reimbursement codes are to be developed as well as dedicated booking agendas. This method can replace a face-to-face visit in many hepatological conditions such as compensated cirrhosis or in patients with ALD who have reached durable medical control of their disease, since in a scenario of substantial clinical stability, it is not necessary to carry out a physical examination of the patient but only to collect, even indirectly, clinical-laboratory parameters easily communicated by the patient himself.

We would like to thank Veronica Fortuzzi for her Excellent English language editing, Laura Conti for her statistical review, and Giulio Antonelli for his contribution in revising the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Koller T, Restin T, Rodrigues AT S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Forouzesh M, Rahimi A, Valizadeh R, Dadashzadeh N, Mirzazadeh A. Clinical display, diagnostics and genetic implication of novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemic. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:4607-4615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Boettler T, Newsome PN, Mondelli MU, Maticic M, Cordero E, Cornberg M, Berg T. Care of patients with liver disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: EASL-ESCMID position paper. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 66.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Aghemo A, Masarone M, Montagnese S, Petta S, Ponziani FR, Russo FP; Associazione Italiana Studio Fegato (AISF). Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on the management of patients with liver diseases: A national survey by the Italian association for the study of the Liver. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:937-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwi M, Boparai N, King D. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Lim SL, Woo KL, Lim E, Ng F, Chan MY, Gandhi M. Impact of COVID-19 on health-related quality of life in patients with cardiovascular disease: a multi-ethnic Asian study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ciążyńska M, Pabianek M, Szczepaniak K, Ułańska M, Skibińska M, Owczarek W, Narbutt J, Lesiak A. Quality of life of cancer patients during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychooncology. 2020;29:1377-1379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Falcone R, Grani G, Ramundo V, Melcarne R, Giacomelli L, Filetti S, Durante C. Cancer Care During COVID-19 Era: The Quality of Life of Patients With Thyroid Malignancies. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Azzam NA, Aljebreen A, Almuhareb A, Almadi MA. Disability and quality of life before and during the COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:256-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Algahtani FD, Hassan SU, Alsaif B, Zrieq R. Assessment of the Quality of Life during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica. Decreto Del Presidente Del Consiglio Dei Ministri 9 marzo 2020. Ulteriori disposizioni attuative del decreto-legge 23 febbraio 2020, n. 6, recante misure urgenti in materia di contenimento e gestione dell’emergenza epidemiologica da COVID-19, applicabili. 2020; decreto-legge 9 marzo 2020, n. 14. |

| 11. | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Best practices for developing surveys and questionnaires on the impacts of COVID-19 on fisheries and aquaculture. 2020 June Version 1.0. [cited 25 May 2021]. Available From: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwibuILyzcD1AhW. |

| 12. | Rucci P, Taliani G, Cirrincione L, Alberti A, Bartolozzi D, Caporaso N, Colombo M, Coppola R, Chiaramonte M, Craxi A, De Sio I, Floreani AR, Gaeta GB, Persico M, Secchi G, Versace I, Mele A. Validity and reliability of the Italian version of the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ-I) for the assessment of health-related quality of life. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:850-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, Mensi S, Niolu C, Pacitti F, Di Marco A, Rossi A, Siracusano A, Di Lorenzo G. COVID-19 Pandemic and Lockdown Measures Impact on Mental Health Among the General Population in Italy. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 709] [Cited by in RCA: 767] [Article Influence: 153.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moccia L, Janiri D, Pepe M, Dattoli L, Molinaro M, De Martin V, Chieffo D, Janiri L, Fiorillo A, Sani G, Di Nicola M. Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:75-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 76.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Albillos A, Lario M, Álvarez-Mon M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1385-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 691] [Cited by in RCA: 848] [Article Influence: 77.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Kushner T, Cafardi J. Chronic Liver Disease and COVID-19: Alcohol Use Disorder/Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease, Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease/Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis, Autoimmune Liver Disease, and Compensated Cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2020;15:195-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kovalic AJ, Satapathy SK, Thuluvath PJ. Prevalence of chronic liver disease in patients with COVID-19 and their clinical outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol Int. 2020;14:612-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Landewé RB, Machado PM, Kroon F, Bijlsma HW, Burmester GR, Carmona L, Combe B, Galli M, Gossec L, Iagnocco A, Isaacs JD, Mariette X, McInnes I, Mueller-Ladner U, Openshaw P, Smolen JS, Stamm TA, Wiek D, Schulze-Koops H. EULAR provisional recommendations for the management of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in the context of SARS-CoV-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:851-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Leoni MC, Amelung L, Lieveld FI, van den Brink J, de Bruijne J, Arends JE, van Erpecum CP, van Erpecum KJ. Adherence to ursodeoxycholic acid therapy in patients with cholestatic and autoimmune liver disease. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2019;43:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sockalingam S, Blank D, Abdelhamid N, Abbey SE, Hirschfield GM. Identifying opportunities to improve management of autoimmune hepatitis: evaluation of drug adherence and psychosocial factors. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1299-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pape S, Schramm C, Gevers TJ. Clinical management of autoimmune hepatitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:1156-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Weiler-Normann C, Lohse AW. Treatment adherence - room for improvement, not only in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1168-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |