Published online Mar 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i3.108

Peer-review started: September 13, 2019

First decision: September 26, 2019

Revised: December 28, 2019

Accepted: February 17, 2020

Article in press: February 17, 2020

Published online: March 27, 2020

Processing time: 192 Days and 12.7 Hours

Sickle cell hepatopathy (SCH) is an inclusive term referring to any liver dysfunction among patients with sickle cell disease. Acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis is one of the rarest and most fatal presentations of SCH. We present the 23rd reported case of liver transplantation (LT) for SCH; a rare case of acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis managed with LT from a hepatitis C virus (HCV) nucleic acid amplification test positive donor.

A 29-year-old male with a past medical history of sickle cell disease presented with vaso-occlusive pain crisis. On examination, he had jaundice and a soft, non-tender abdomen. Initially he was alert and fully oriented; within 24 h he developed new-onset confusion. Laboratory evaluation was notable for hyperbilirubinemia, leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, acute kidney injury and elevated international normalized ratio (INR). Imaging by ultrasound and computed tomography scan suggested a cirrhotic liver morphology with no evidence of biliary ductal dilatation. The patient was diagnosed with acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis after excluding competing etiologies of acute liver injury. He underwent LT from an HCV nucleic acid amplification test positive donor 9 d after initial presentation. The liver explant was notable for widespread sinusoidal dilatation with innumerable clusters of sickled red blood cells and cholestasis. On postoperative day 3, HCV RNA was detectable in the patient's peripheral blood and anti-HCV therapy with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir was initiated on postoperative day 23. He subsequently achieved sustained virologic response after completing 3 mo of therapy and has been followed clinically for 12 mo post-transplant.

This case highlights the utility of LT as a viable treatment option for acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis.

Core tip: Acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis is a rare and life-threatening form of sickle cell hepatopathy, with a mortality rate approaching 40%. Patients typically present with fever, abdominal pain and jaundice. Rarely, it may progress to an acute liver failure phenotype, commonly associated with multi-system organ failure. Diagnosis is made after excluding other causes of acute liver injury. Treatment options include exchange blood transfusion and liver transplantation.

- Citation: Alkhayyat M, Saleh MA, Zmaili M, Sanghi V, Singh T, Rouphael C, Simons-Linares CR, Romero-Marrero C, Carey WD, Lindenmeyer CC. Successful liver transplantation for acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis: A case report and review of the literature. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(3): 108-115

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i3/108.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i3.108

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common inherited blood disorder affecting up to 100000 Americans. It is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a point mutation in the beta chain of chromosome 11 with a substitution of glutamic acid to valine. This substitution with a hydrophobic amino acid allows hemoglobin S (HbS) to polymerize on deoxygenation, forming rod-like polymers and resulting in poorly deformable sickled cells. Decreased red blood cell (RBC) pliability precipitates hemolysis and increases RBC membrane adhesiveness with the endothelium, which predisposes to vaso-occlusion of small blood vessels, which is often followed by reperfusion injury[1].

Involvement of the hepatobiliary system is observed in 10%-40% of sickle cell crises[1]. Hepatobiliary involvement may be related to conditions that are not unique to SCD but are more commonly seen in this group of patients compared to the general population as a result of chronic hemolysis and the resultant need for frequent blood transfusions. These conditions include cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, acute cholangitis, pancreatitis, viral hepatitis and hemosiderosis. Hepatobiliary manifestations unique to patients with SCD include acute sickle cell hepatic crisis, acute hepatic sequestration and acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis (the result of RBC sickling inside the hepatic sinusoids) (Table 1).

| SCD manifestation | Pathophyiology of the disease | Histopathology | Clinical presentation | Amino-transferases | ALP | Bilirubin | Management |

| Acute sickle cell hepatic crises | Sickled RBCs obstruct liver sinusoids causing ischemic infarction | - Presence of sickle cell aggregates in the liver sinusoids | Fever, abdominal pain, jaundice and tender hepatomegaly | Elevated up to 3 fold the upper limit of normal followed by rapid resolution | Normal to slighly elevated | Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia up to 15 mg/dL, usually normalizes within 2 weeks | Supportive; hydration, oxygenation, pain control and blood exchange as needed |

| - Kupffer cell hypertrophy and centrilobular necrosis | |||||||

| Acute hepatic sequestration | Kupffer cell erythrophagocytosis traps sickled RBCs resulting in blood pooling within liver sinusoids | - Presence of dilated blood-filled liver sinusoids | Sudden severe RUQ pain and rapidly worsening anemia with appropriate reticulocytosis; severe cases can present with shock and hepatomegaly | Normal | Elevated; up to 650 U/L | Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia up to 24 mg/dL | Cautious blood transfuison or exchange transfusion; excessive transfusion can result in rapid rise of Hb during resolution phase precipitating stroke and heart failure |

| Acute intrahepatic cholestasis | Diffuse sickling in liver sinusoids leading to widespread ischemia as well as Kupffer cell hypertrophy and extramedullary hematopoiesis which contribute to cholestasis | - Presence of massively dilated blood sinusoids with clusters of sickled RBCs | Fever, RUQ pain, acute liver failure and multi-system organ failure | Elevated; typically > 1000 U/L | Normal or elevated up to >1000 U/L | Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia up to > 30 mg/dL | Supportive with exchange transfusion and LT |

| - Presence of intracanalicular and intraductal cholestasis | |||||||

| - Ballooning of hepatocytes, necrosis, inflammation | |||||||

| Sickle cell cholangiopathy | Incomplete occlusion of the peribiliary vascular plexus results in hypoxia and dilatation of the bile ducts; recurrent insults can result in ischemic stricture | - Presence of ischemic necrosis and fibrosis of the bile ducts | Jaundice and biliary stone compications, imaging can reveal non-obstructive bile duct dilatation and/or obstructive biliary strictures | Normal or elevated | Elevated | Elevated | ERCP stenting and balloon dilatation, LT |

A 29-year-old African American male with a past medical history of SCD (Hb SS), maintained with exchange transfusions every 4-6 wk, with resultant hemosiderosis and cirrhosis presented with vaso-occlusive pain crisis in his lower extremities and uncontrolled epistaxis. His outpatient medications included deferasirox, folic acid and oxycodone. He denied tobacco, alcohol or drug use.

On initial examination, his vital signs were within normal limits. He was markedly jaundiced and was alert and fully oriented. His abdomen was soft without tenderness or organomegaly and with normal bowel sounds. Within 24 h of presentation, he developed new-onset confusion attributed to hepatic encephalopathy.

Laboratory evaluation was notable for conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with a total serum bilirubin 57 mg/dL and direct serum bilirubin 30 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 306 U/L, aspartate transaminase 227 U/L, and alanine transaminase 54 U/L. White blood cell count was 38.6 k/µL, hemoglobin was 6.3 g/dL and platelet count was 39 k/µL. Coomb's testing was negative, fibrinogen was 412 mg/dL, and INR was 2.3. His model for end-stage liver disease-sodium score was 40.

An extensive workup for acute liver injury was undertaken. Acute and chronic viral hepatitis testing was negative. Serologic testing for autoimmune hepatitis and genetic causes of liver disease, including hereditary hemochromatosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and Wilson disease was negative. His ferritin was elevated at 1399 ng/mL. His arterial ammonia level was 72 µmol/L. He was diagnosed with an acute kidney injury with a serum creatinine of 3.48 mg/dL (baseline creatinine 0.6-0.7 mg/dL).

A liver vascular ultrasound revealed a cirrhotic liver morphology with patent hepatic vasculature and appropriate flow. An abdominal computed tomography scan showed changes consistent with cirrhosis without biliary ductal dilatation.

The patient was diagnosed with acute-on-chronic liver failure with multi-system organ failure secondary to acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis based on the presence of new-onset acute liver injury, encephalopathy, coagulopathy, and acute kidney injury.

He was admitted to the medical intensive liver unit for further management. He required intubation and mechanical ventilation for acute hypoxic respiratory failure secondary to acute chest syndrome; for this he was treated with empirical vancomycin and meropenem. An exchange transfusion was initiated with subsequent decrease of HbS level from 56.3 to 8.2 g/dL. Despite the exchange transfusion, his hepatic synthetic function did not improve; he was rapidly evaluated and subsequently listed with a model for end-stage liver disease-sodium score of 40 for urgent liver transplantation (LT) for acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis.

The pre-operative evaluation was coordinated by a multidisciplinary team involving hepatology, infectious disease, dermatology, dentistry, anesthesiology, transplant surgery, critical care and apheresis specialists. Nine days after initial presentation, the patient underwent LT from a brain dead, hepatitis C virus (HCV) nucleic acid test (NAT) positive donor utilizing standard piggyback technique and a duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis. The explanted liver was found to be enlarged, measuring 25.4 cm x 16.6 cm x 10.5 cm and weighing 2125.6 g. The capsule was focally micronodular predominantly on the posterior surface. On cut section, the parenchyma was red-brown and appeared congested with focal micronodular areas. The hepatic vasculature and bile ducts were normal.

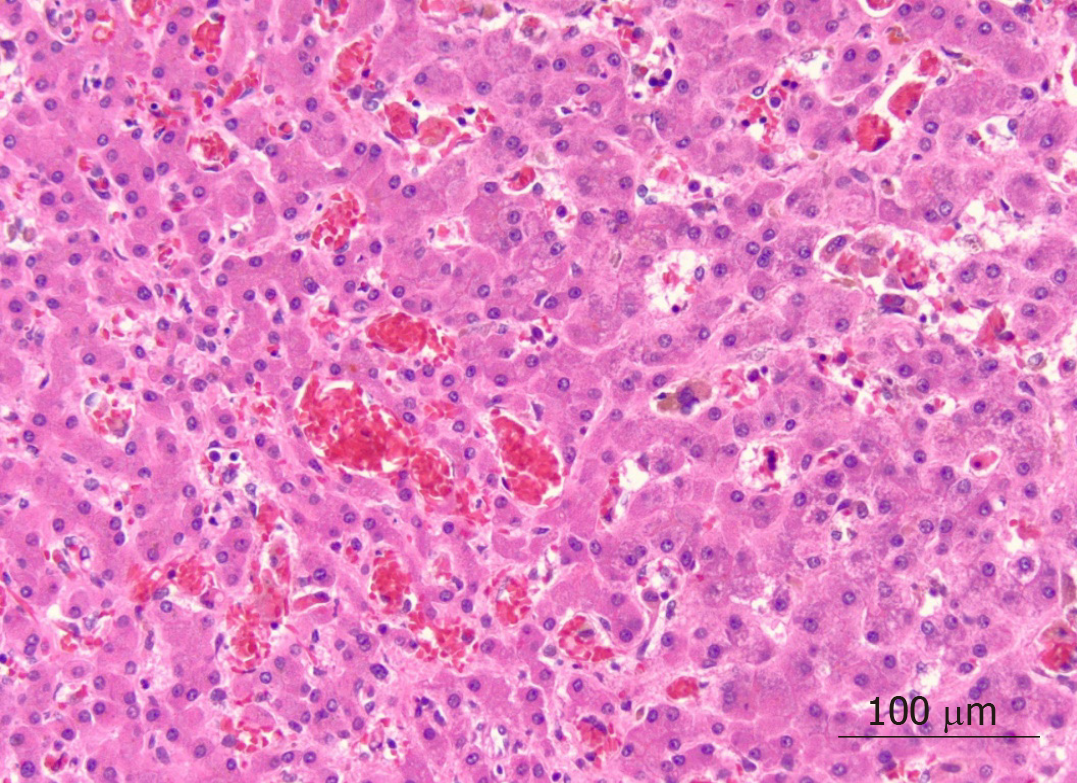

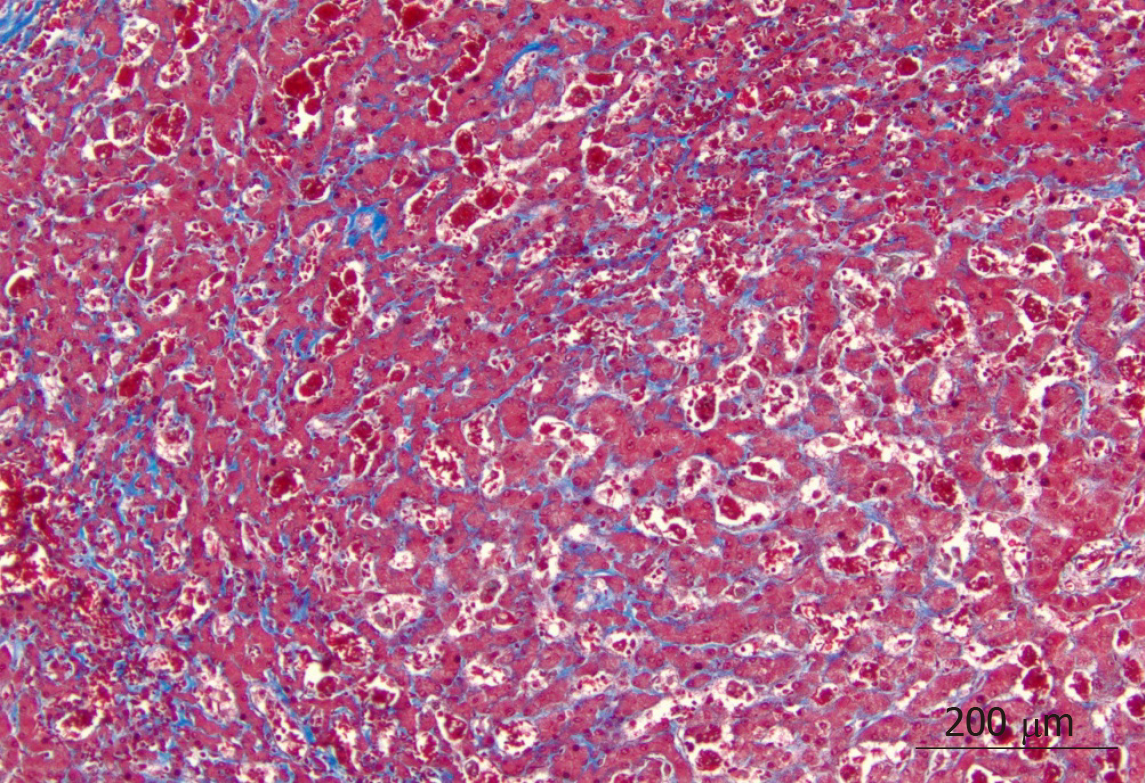

On microscopic examination, the liver parenchyma showed widespread sinusoidal dilatation with innumerable clusters of sickled red blood cells, scattered pigmented histiocytes and cholestasis. The trichrome stain highlighted extensive sinusoidal fibrosis and established portal-portal bridging fibrosis with evolution toward cirrhosis (stage 3-4, scale 0-4, Batts-Ludwig methodology). The iron stain was notable for patchy hepatocellular and Kupffer cell siderosis (2+) (Figures 1 and 2).

Immediately following LT, exchange transfusion was resumed and the patient was started on immunosuppression induction therapy with antithymocyte globulin. He was also initiated on mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus and a steroid taper for maintenance of immunosuppression. On postoperative day 3, HCV ribonucleic acid was found to be > 100000000 IU/mL. Genotyping revealed HCV genotype 1A; anti-HCV therapy with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir was started on post-operative day 23 after insurance approval. The patient progressed routinely and was discharged. He achieved sustained virologic response after completing 3 mo of anti-HCV therapy. At 12 mo post-operatively, his liver synthetic function is preserved on chronic tacrolimus immune suppressive therapy; he undergoes monthly exchange transfusions with a target HbS < 20%.

Only 22 cases of LT for SCH have been reported in the literature. The majority of transplants have been performed for acute liver failure (ALF) secondary to acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis. We report the 23rd LT for SCH; the first reported case of an HCV NAT positive donor that facilitated urgent LT for an HCV NAT negative patient with acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis. Our patient subsequently achieved sustained virologic response after being treated with 3 mo of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir.

Sickle cell hepatopathy (SCH) is an inclusive term referring to any liver dysfunction among patients with SCD. SCH can present with both acute or chronic liver dysfunction, but has primarily been used in the literature to describe the acute hepatic manifestations of SCD. At times, SCH has been used to denote acute intrahepatic cholestasis specifically[1-6].

Acute intrahepatic cholestasis related to SCD is the most severe, and often fatal, form of SCH, associated with a mortality rate approaching 40%. Patients may present with severe acute hepatic crisis with fever, right upper quadrant pain and leukocytosis; however, this condition is characteristically accompanied by significant jaundice and can rapidly progress into ALF. Patients typically experience a dramatic increase in conjugated bilirubin with reported levels ranging between 30 and 273 mg/dL. Hemolysis and acute kidney injury also contribute to hyperbilirubinemia. Liver biochemistries including the aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase and alkaline phosphatase levels may reach values exceeding1000 mg/dL; however, normal to only slightly elevated values are possible. Coagulopathy, evidenced by elevated prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, INR and hypo-fibrinoginemia, is typically seen. Multi-factorial acute kidney injury is commonly observed as well. To date, no cohesive list of diagnostic criteria has been proposed; we propose that multi-system organ failure with extreme hyperbilirubinemia and accompanied by altered mental status in patients with SCD should raise the clinical index of suspicion for acute intrahepatic cholestasis with an ALF phenotype[1,2].

Liver biopsy will typically demonstrate dilated blood sinusoids with clusters of sickled RBCs, associated with fibrosis and as intracanalicular and intraductal cholestasis[1,3,7]. Findings of extramedullary hematopoiesis and Kupffer cell hypertrophy with intracellular engulfed sickled RBCs have also been described in the literature[3]. According to the degree of hypoxic injury, ballooning of hepatocytes, and in more severe cases, widespread anoxic necrosis with areas of acute and chronic inflammation have also been reported[1,8]. Based on the described histopathologic characteristics, it is believed that this condition results from diffuse sickling in the blood sinusoids leading to widespread ischemia, hepatocyte injury and fibrosis[1]. Kupffer cell hypertrophy and extramedullary hematopoiesis may also contribute to liver sinusoidal obstruction with compression of the adjacent bile ducts, contributing to cholestasis.

A recent report in the literature of acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis by Kwun Lui et al[3] described a more complex histological pattern of injury, including a combination of centrizonal fibrosis, occasional occlusion and constriction of the central veins, and sinusoidal fibrosis. This pattern more closely resembles the histological findings of chronic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome and veno-occlusive disease. This finding prompts the suggestion that intrahepatic cholestasis in SCD may result from RBC-mediated damage of small vessel endothelium, resulting in endothelial cell death and subsequent fibrosis of the small hepatic veins and sinusoids. Progression of this process would result in obstruction and distention of the sinusoids. It has been therefore hypothesized that endothelial dysfunction is the direct consequence of ischemic RBC-mediated injury in the small outflow veins and sinusoids.

In patients with SCD and intra-hepatic cholestasis, cause of death is typically related to multi-system organ failure. Therapy is aimed at aggressive supportive measures, including exchange transfusions to replace HbS and correct anemia. Coagulopathy is usually treated with blood product and factor transfusions. Temporary renal replacement therapy may be required for acute kidney injury; renal function should correct with improvement of liver function[1]. If supportive measures fail, LT remains the only viable therapeutic option. Outcomes for patients with intrahepatic cholestasis undergoing LT are summarized in Table 2. Recurrence of this disease process has been reported after LT; the role of hydroxyurea to prevent sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis is uncertain[9,10].

| Ref. | Year | Number of cases | Age of the patient | Outcomes |

| Emre et al[15] | 2000 | 1 | 6 | First transplant was complicated by graft failure from veno-occlusive disease, required re-LT. |

| Second transplant was complicated by graft failure from hepatic artery thrombosis, required re-LT. | ||||

| The patient died 6 mo after third LT from sepsis. | ||||

| Ross et al[18] | 2002 | 1 | 49 | The patient died 22 mo after LT due to pulmonary embolism. |

| Gilli et al[19] | 2002 | 1 | 22 | The patient was alive 3 mo after LT. |

| Baichi et al[7] | 2005 | 1 | 27 | Post-LT course was complicated by sepsis, multiorgan failure, perihepatic hematoma and hemorrhagic ascites; the patient died 35 d after LT. |

| Mekeel et al[9] | 2007 | 2 | 8,17 | Patients were followed up over a mean period of 4.2 yr. |

| Patient 1 was alive at end of follow-up with mild recurrent HCV. | ||||

| Patient 2 had recurrent sickle cell hepatopathy post-transplant and died of cerebral complications 6 yr following LT. | ||||

| Hurtova et al[6] | 2011 | 5 | 32-47 | Patient 1 died of recurrent HCV-induced decompensated cirrhosis and sepsis 11 yr after LT. |

| Patient 2 had recurrent HCV with moderate fibrosis; died of ischemic cholangitis and sepsis after 4 yr after LT. | ||||

| Patient 3 had recurrent HCV infection. He was alive 8 yr after LT. | ||||

| Patient 4's post-operative course was complicated by posterior leukoencephalopathy; the patient died from sepsis 16 mo after LT. | ||||

| Patient 5 developed biliary strictures requiring stenting. The patient was alive 42 mo after LT. | ||||

| Blinder et al[20] | 2013 | 1 | 37 | Immediate post-LT course was complicated with seizure and respiratory failure. The patient had no post-operative SCD-related complications in the 12 mo after transplant and was maintained on hydroxyurea without need for exchange transfusion. |

| Lui et al[3] | 2018 | 1 | 29 | The patient was alive 7 mo after LT with no reported complications. |

In patients with SCD, an acute presentation of acute-on-chronic liver failure with an ALF phenotype has been reported in patients with underlying chronic liver disease related to chronic viral hepatitis and/or iron overload[3]. Vaso-occlusive events may also precipitate acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. Patients are at elevated risk of hepatic decompensation despite exchange transfusion given their low hepatic synthetic reserve; LT should accordingly be considered as a viable rescue therapy in selected patients[6].

Two case series describing LT for SCD patients are present in the literature. The first series described 6 patients with 1-, 5- and 10-year survival rates of 83.3%, 44.4% and 44.4% respectively[6]. The second series described 3 pediatric patients, followed for a mean of 4.3 years, with a reported survival rate of 66%[9].

The risk of vaso-occlusive crisis is increased peri-operatively, and crises may involve the transplanted liver. It has been recommended to initiate exchange transfusion before surgery with an HbS target of < 20%-30% and for the HbS level to be maintained between 8 and 10 g/dL post-operatively in the long term[6,9].

Iron overload is a risk factor for progression of hepatic fibrosis related to chronic HCV infection among transplanted liver organs. Hemosiderosis should be managed by minimizing simple blood transfusions as able, by considering exchange blood transfusion as an alternative, and with iron chelators as indicated. Total body iron stores should be monitored serologically on a regular basis. Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for determination of hepatic iron concentration, however; magnetic resonance imaging in combination with serum ferritin level has been proposed as a non-invasive alternative[11,12]. However, serum ferritin levels may vary over time in the setting of infectious or inflammatory processes, vaso-occlusive crises and liver dysfunction[13]. Chelation therapy is indicated in adults after receiving 20-30 blood units, in patients with a serum ferritin > 3000 ng/mL with a hepatic iron index of > 7-9 mg/g dry weight[14].

The evaluation of abnormal liver biochemistries after LT may be challenging in patients with SCD; it can be challenging to non-invasively differentiate acute and/or chronic rejection and infectious processes from the normal hepatic pathophysiology of SCD. As part of normal SCD physiology, kupffer cells will continue to engulf sickled RBCs, which can lead to congestion of the liver allograft and mild elevation of aminotransferases and bilirubin levels[15]. Furthermore, low grade fever and leukocytosis are commonly seen in patients with SCD during vaso-occlusive crises[16]. Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for evaluation of possible rejection following LT[17].

In conclusion, we present a rare case of acute sickle intrahepatic cholestasis managed with successful LT. This case represents the first report of an HCV NAT positive allograft being transplanted into an HCV negative SCD patient, and is the 23rd reported case of LT in SCD patients overall. Unfortunately, LT will not reverse the underlying pathophysiology of SCD; diligent post-transplant hematologic and immunosuppressive management care is needed in these cases. As our understanding of SCH evolves, paralleling technical advances in LT, post-LT management should be aimed at improving quality of life and optimizing survival.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Grawish M, Nkachukwu S S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Shah R, Taborda C, Chawla S. Acute and chronic hepatobiliary manifestations of sickle cell disease: A review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2017;8:108-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Friedman LS. Liver transplantation for sickle cell hepatopathy. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:483-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kwun Lui S, Krasinskas A, Shah R, Tracht JM. Orthotropic Liver Transplantation for Acute Intrahepatic Cholestasis in Sickle Cell Disease: Clinical and Histopathologic Features of a Rare Case. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:411-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Banerjee S, Owen C, Chopra S. Sickle cell hepatopathy. Hepatology. 2001;33:1021-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gardner K, Suddle A, Kane P, O'Grady J, Heaton N, Bomford A, Thein SL. How we treat sickle hepatopathy and liver transplantation in adults. Blood. 2014;123:2302-2307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hurtova M, Bachir D, Lee K, Calderaro J, Decaens T, Kluger MD, Zafrani ES, Cherqui D, Mallat A, Galactéros F, Duvoux C. Transplantation for liver failure in patients with sickle cell disease: challenging but feasible. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:381-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Baichi MM, Arifuddin RM, Mantry PS, Bozorgzadeh A, Ryan C. Liver transplantation in sickle cell anemia: a case of acute sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis and a case of sclerosing cholangitis. Transplantation. 2005;80:1630-1632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Greenberg M, Daugherty TJ, Elihu A, Sharaf R, Concepcion W, Druzin M, Esquivel CO. Acute liver failure at 26 weeks' gestation in a patient with sickle cell disease. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1236-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mekeel KL, Langham MR, Gonzalez-Peralta R, Fujita S, Hemming AW. Liver transplantation in children with sickle-cell disease. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:505-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malik A, Merchant C, Rao M, Fiore RP. Rare but Lethal Hepatopathy-Sickle Cell Intrahepatic Cholestasis and Management Strategies. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:840-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Adam R, Karam V, Cailliez V, O Grady JG, Mirza D, Cherqui D, Klempnauer J, Salizzoni M, Pratschke J, Jamieson N, Hidalgo E, Paul A, Andujar RL, Lerut J, Fisher L, Boudjema K, Fondevila C, Soubrane O, Bachellier P, Pinna AD, Berlakovich G, Bennet W, Pinzani M, Schemmer P, Zieniewicz K, Romero CJ, De Simone P, Ericzon BG, Schneeberger S, Wigmore SJ, Prous JF, Colledan M, Porte RJ, Yilmaz S, Azoulay D, Pirenne J, Line PD, Trunecka P, Navarro F, Lopez AV, De Carlis L, Pena SR, Kochs E, Duvoux C; all the other 126 contributing centers (www. eltr.org) and the European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). 2018 Annual Report of the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR) - 50-year evolution of liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2018;31:1293-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 47.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wun T, Hassell K. Best practices for transfusion for patients with sickle cell disease. Hematol Rep. 2010;1. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Harmatz P, Butensky E, Quirolo K, Williams R, Ferrell L, Moyer T, Golden D, Neumayr L, Vichinsky E. Severity of iron overload in patients with sickle cell disease receiving chronic red blood cell transfusion therapy. Blood. 2000;96:76-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Raghupathy R, Manwani D, Little JA. Iron overload in sickle cell disease. Adv Hematol. 2010;2010:272940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Emre S, Kitibayashi K, Schwartz ME, Ahn J, Birnbaum A, Thung SN, Miller CM. Liver transplantation in a patient with acute liver failure due to sickle cell intrahepatic cholestasis. Transplantation. 2000;69:675-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ahmed AE, Ali YZ, Al-Suliman AM, Albagshi JM, Al Salamah M, Elsayid M, Alanazi WR, Ahmed RA, McClish DK, Al-Jahdali H. The prevalence of abnormal leukocyte count, and its predisposing factors, in patients with sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia. J Blood Med. 2017;8:185-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Alpna R, Lisa R, Roberto J, Randazzo C, Licata A, Almasio PL. Liver Biopsy After Liver Transplantation. In: Randazzo C, Licata A, Almasio PL. Liver Biopsy - Indications, Procedures, Results. Randazzo C, Licata A, Almasio PL. London: IntechOpen, 2012. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Ross AS, Graeme-Cook F, Cosimi AB, Chung RT. Combined liver and kidney transplantation in a patient with sickle cell disease. Transplantation. 2002;73:605-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gilli SC, Boin IF, Sergio Leonardi L, Luzo AC, Costa FF, Saad ST. Liver transplantation in a patient with S(beta)o-thalassemia. Transplantation. 2002;74:896-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Blinder MA, Geng B, Lisker-Melman M, Crippin JS, Korenblat K, Chapman W, Shenoy S, Field JJ. Successful orthotopic liver transplantation in an adult patient with sickle cell disease and review of the literature. Hematol Rep. 2013;5:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |