Published online Feb 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i2.226

Peer-review started: October 16, 2018

First decision: November 15, 2018

Revised: December 13, 2018

Accepted: January 9, 2019

Article in press: January 9, 2019

Published online: February 27, 2019

Processing time: 133 Days and 19.1 Hours

Necrolytic acral erythema (NAE) is a rare dermatological disorder, which is associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection or zinc deficiency. It is characterized by erythematous or violaceous lesions occurring primarily in the lower extremities. The treatment includes systemic steroids and oral zinc supplementation. We report a case of NAE in a 66-year-old human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/HCV co-infected woman with NAE. NAE is rarely reported in co-infected patients and the exact mechanisms of pathogenesis are still unclear.

A 66-year-old HIV/HCV co-infected female patient presented with painless, non-pruritic rash of extremities for one week and underwent extensive work-up for possible rheumatologic disorders including vasculitis and cryoglobulinemia. Punch skin biopsies of right and left thigh revealed thickened parakeratotic stratum corneum most consistent with NAE. Patient was started on prednisone and zinc supplementation with resolution of the lesions and improvement of rash.

Clinicians should maintain high clinical suspicion for early recognition of NAE in patients with rash and HCV.

Core tip: Necrolytic acral erythema (NAE) is a rare dermatological entity associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and zinc deficiency. Aim of the case report is to describe the occurrence of NAE in a human immunodeficiency virus/HCV coinfected patient, elucidate the clinical characteristics, pathophysiologic mechanisms and increase clinician awareness about diagnosis and management.

- Citation: Oikonomou KG, Sarpel D, Abrams-Downey A, Mubasher A, Dieterich DT. Necrolytic acral erythema in a human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus coinfected patient: A case report. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(2): 226-233

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i2/226.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i2.226

Necrolytic acral erythema (NAE) is a rare dermatological entity. While the disease is frequently associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection or zinc deficiency[1-4], the pathogensis is poorly understood. NAE is characterized by erythematous lesions, violaceous papules, bullae and superficial skin erosions occurring primarily in the lower extremities and dorsal feet. Associated symptoms include pruritus, pain, burning and dysesthesia. NAE is an infrequent extrahepatic manifestation of hepatitis C with a much less frequent overall prevalence of 1.7% compared to cryoglobulinemia, porphyria cutanea tarda, lichen planus[5,6]. Additionally, NAE has been reported in patients with zinc deficiency and less frequently in association with vaccination against hepatitis B[2,7]. NAE should be differentiated from psoriasis and eczematous dermatitis, lichen simplex chronicus, hypertrophic lichen planus, acrokeratoelastoidosis, and acrokeratosis paraneoplastica. Zinc supplementation and treatment of underlying hepatitis C have been related to favorable response. We describe a case of a patient with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C co-infections diagnosed with NAE.

A 66-year-old woman, with past medical history of well-controlled HIV infection on antiretroviral (ARV) therapy with azatanavir/ritonavir and abacavir/lamivudine and untreated chronic hepatitis C (Genotype 1b) with cirrhosis, who presented with chief complaint of painless, non-pruritic rash for one week. The rash began as diffuse, patchy erythematous lesions of bilateral lower extremities, starting at her feet but progressing up her legs to her thighs. She noted associated edema, but denied fevers, chills, joint pain, oral lesions or ulcers and weakness or numbness in her extremities. She was not sexually active and denied any allergies. Patient was recently discharged from the hospital after a COPD exacerbation. She was discharged on a brief oral prednisone taper, which she completed prior to presentation, but was still taking when the rash developed. On admission patient was afebrile and hemodynamically stable.

Her physical exam revealed dusky erythematous patches of non-blanching palpable petechiae and purpura on bilateral calves and thighs as well as on her right forearm. She also had vesiculobullous lesions on bilateral lower extremities with several scattered erosions, without lesions on palms or soles and no oral or genital lesions (Figure 1). Nikolsky sign was negative. Patient underwent extensive work-up for possible rheumatologic disorders including vasculitis and cryoglobulinemia.

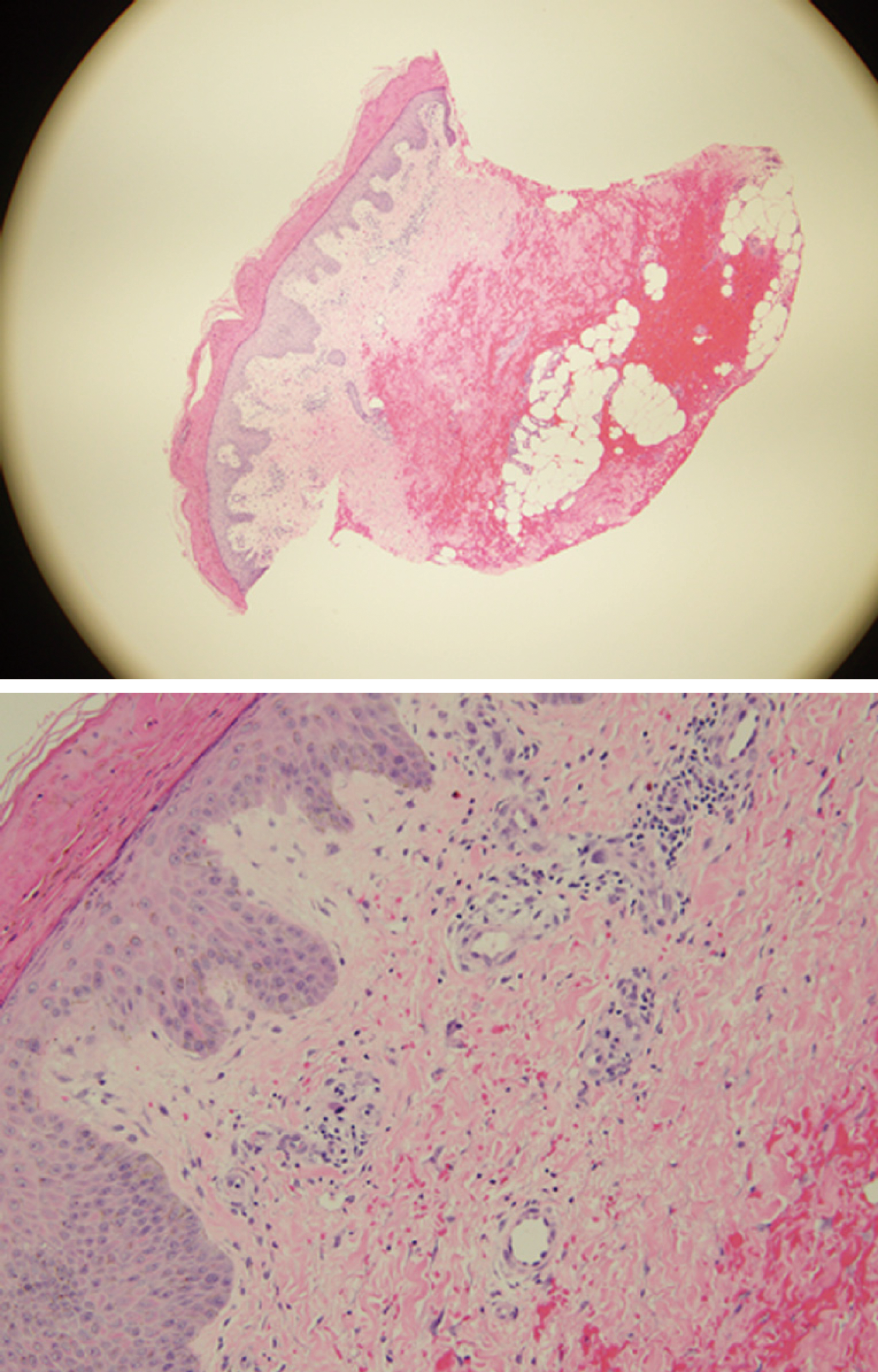

Laboratory findings are shown in Table 1. Dermatology consulted during her hospital stay and performed punch skin biopsies of right and left thigh. Pathology reported thickened parakeratotic stratum corneum most consistent with NAE (Figure 2).

| Parameters | Reference range |

| White blood cell count - 15.3 | 4.5-11 K/uL |

| Hematocrit - 44.5 | 34%-47% |

| Hemoglobin – 13.6 | 11.7-15 g/dL |

| Platelet count – 376000 | 150-450 K/uL |

| Blood urea nitrogen - 42 | 7-20 mg/dL |

| Creatinine – 1.28 | 0.5-1.1 mg/dL |

| AST - 17 | < 36 U/L |

| ALT - 23 | < 46 U/L |

| Total bilirubin - 2.0 | 0.1-1.2 mg/dL |

| Direct bilirubin – 1.0 | < 0.9 mg/dL |

| gGT - 145 | 0-60 IU/L |

| Total protein – 6.4 | 6-8.3 g/dL |

| Albumin – 2.6 | 3.5-5.0 g/dL |

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation rate - 68 | (0-24 mm/h) |

| C-reactive protein – 78.32 | < 5.1 mg/L |

| INR – 1.0 | 0.9-1.1 |

| C3 - 156 | 90-180 mg/dL |

| cANCA - negative | Negative |

| pANCA - negative | Negative |

| Rheumatoid factor - < 15 | 0-15 IU/mL |

| Anti-SSA – negative | Negative |

| Anti-SSB – negative | Negative |

| Anti-CCP – negative | Negative |

| RPR – non-reactive | Non-reactive |

| Cryoglobulins – negative | Negative |

| Antinuclear antibodies - negative | Negative |

| AntidsDNA – negative | Negative |

| HIV RNA – undetectable | < 20 copies/mL |

| CD4 – 564/25% | Cells/mL |

| HCV-RNA – 346755 genotype 1B | < 15 IU/mL |

NAE in an HIV/HCV co-infected patient.

Patient was started on prednisone 20 mg daily along with zinc supplementation given her low serum zinc levels. She had resolution of her vesiculobullous lesions and improvement of erythema. Unfortunately, no clinical images were obtained after her clinical improvement.

Patient was discharged to follow-up with her infectious diseases provider for initiation of hepatitis C treatment. She was initiated on sofosbuvir/veltapasvir and her ARV was transitioned to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide to avoid any drug drug interactions.

Necrolytic erythemas include NAE, necrolytic migratory erythema, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and various dermopathies due to nutrient deficiencies[8]. NAE was first described by El-Ghandour et al[4] in a cohort of Egyptian patients. NAE is observed most commonly in women and with age of onset around 40 years[2]. In early stages, skin changes consist of erythematous papules and plaques with early skin erosion. During the second stage, there is increasing thickness of the papules and lichenification followed by hyperpigmentation often associated with necrosis of superficial epidermis. In the late stage hyperpigmentation becomes more prominent. The most common location of lesions is the back of the feet and toes, and also in lower extremities along the surface of the Achilles tendon, the malleoli, legs and knees. Histological characteristics include acanthosis, spongiosis in early stages of the disease process along with psoriasiform hyperplasia in the later stages. In advanced disease, parakeratosis and possible necrosis of keratinocytes can be seen. These histopathological findings are non-specific and high clinical suspicion is required for early diagnosis[9].

The pathogenesis of NAE is unknown and several mechanisms have been proposed. Potential etiologies include the metabolic changes associated with liver dysfunction and diabetes[10-12]. Hypoalbuminemia, hypoaminoacidemia and hyperglucagonemia are all associated with inducing inflammatory responses[13].

Other proposed mechanisms include mineral deficiencies, primarily zinc. Moneib et al[10] reported that serum levels of zinc are low in patients with NAE. Zinc deficiency causes a reduction in serum transport proteins, such as retinol-binding protein and prealbumin, which impair delivery of the vitamin A, major factor for epidermal proliferation and differentiation[9]. The significance of zinc deficiencies in NAE is further limited by the role of blood measurements for the detection of zinc. Determination levels of zinc levels in future patients with NAE is indicated[11,12].

Additional association has been reported in the setting of hepatitis C. Hepatitis C viral load and genotype may be related to the etiopathogenesis of NAE[13,14]. Although no clear correlation with genotype has been reported in the literature, most article reports describe patients with genotypes 1 and 4[5]. Moreover, in setting of HCV, it seems that there is correlation between severity of lesions and liver damage. While the exact role of zinc deficiency in NAE is unknown and controversial[12].

The treatment of NAE is challenging due to the lack of available data. There are no prospective randomized control trials regarding optimal treatment and most available information is provided from retrospective case series. Regarding treatment of NAE lesions after zinc supplementation, the current literature data are inconsistent. Oral zinc supplementation showed a variable response rate. Zinc with topical tacrolimus, vitamin B1, and vitamin B6 subcutaneous interferon alpha was also reported with variable rates of response and inconsistent benefits[8].

Similarly, there are controversial data about topical or systemic corticosteroids, and zinc supplementation ranging from no response to complete resolution[1]. A trial of brief systemic steroids and oral zinc supplementation and close monitoring for clinical resolution is usually warranted in patients with clinical manifestations of NAE regardless of the serum zinc levels.

In HCV-associated NAE complete or partial resolution has been demonstrated previously with interferon alpha-2b and/or ribavirin, and also with combinations of interferon α-2b and zinc[8]. Interferon free direct acting antiviral regimens have also been shown to be effective and should be offered to chronic HCV patients with the goal of sustained viral response.

It is interesting to note that zinc dysregulation and metabolic alterations can also occur as a result of hepatitis C and HIV infections[2], but to our knowledge case reports of NAE in HCV/HIV co-infected patients are rare. Najarian et al[12] reported a case of NAE in a woman with well controlled HIV and untreated HCV. Patient presented with well-demarcated, painful, pruritic plaques with a distinctive erythematous rim and a distinctive sandal-like pattern of bilateral lower extremities. She was found to have low zinc levels and was treated successfully with oral zinc supplementation. One of the proposed mechanisms for the pathogenesis of NAE in co-infected patients is the increased zinc loss with urine that can be observed with both HCV and HIV. In our patient, urine zinc levels were not routinely checked, and zinc levels after treatment with zinc supplementation were not available.

It is well known that patients with HIV/HCV co-infection have accelerated fibrosis progression due to multiple mechanisms and perhaps this may play a role in NAE. In addition these patients have higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TGF-beta and IFN gamma along with higher levels of lipopolysacchrides which all can enhance inflammatory response. Perhaps this also plays a role in NAE in HIV/HCV co-infected patients.

In terms of appearance of lesions and distribution, there is no significant difference in HCV/HIV co-infected versus mono-infected patients with HCV, or in seronegative patients with isolated zinc deficiency. Skin biopsy can be a powerful tool, but given characteristics of skin lesions, NAE can also be a clinical diagnosis. Table 2 describes the reported cases of NAE, the serologic profiles of patients, and the methods of diagnosis and treatment.

| HCV | HIV | Zinc deficiency | Diagnosis | Treatment | |

| Srisuwanwattana et al[1] | Yes | NA | No | Skin biopsy | Zinc supplementation and topical steroids |

| Kapoor et al[2] | Yes | NA | Yes | Clinical diagnosis | Oral zinc supplementation |

| Jakubovic et al[3] | No | NA | Yes | Skin biopsy | Nutritional Supplementation |

| Abdallah et al[5] | Yes | NA | No | Skin biopsy | Zinc supplementation |

| Pernet et al[7] | No | NA | No | Skin biopsy | Resolved spontaneously |

| Tabibian et al[8] Case 1 | Yes | NA | Yes | Skin biopsy | Zinc supplementation |

| Tabibian et al[8] Case 2 | Yes | NA | Yes | Skin biopsy | Zinc supplementation |

| Das et al[9] | No | NA | NA | Skin biopsy | Zinc supplementation |

| Najarian et al[12] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Skin biopsy | Zinc supplementation |

| Shumez et al[15] | Yes | NA | Yes | Skin biopsy | Zinc supplementation |

| Shaikh et al[16] | Yes | NA | No | Skin biopsy | Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir |

| Wu et al[17] | No | NA | NA | Skin biopsy | Systemic steroids |

| Rahman et al[18] | Yes | NA | NA | Skin biopsy | Systemic steroids and zinc supplementation |

| Botelho et al[19] | Yes | NA | Yes | Skin biopsy | Zinc supplementation |

| Panta et al[20] | No | NA | Low normal levels | Skin biopsy | Oral zinc supplementation and topical steroids |

| Pandit et al[21] Case 1 | No | NA | Yes | Skin biopsy | Oral zinc supplementation |

| Pandit et al[21] Case 2 | No | NA | Yes | Clinical diagnosis | Oral zinc supplementation |

The early diagnosis of NAE is crucial, regardless of the underlying disorder, and early and effective treatment can improve patients quality of life and limit secondary infections through skin lesions. The interpretation of skin histopathology should be performed by experienced pathologists, in order to avoid misinterpretation of the results. Kapoor et al[2] reported a case of NAE in a 44-year-old man with history of HCV, who had findings consistent with eczema or psoriasis on skin biopsy. Patient received multiple courses of treatment with immunosuppressants without significant improvement, was hospitalized multiple times with episodes of cellulitis and suicidal ideation, and after nine years he was treated successfully with oral zinc supplementation with improvement of lesions, pain and functional status[4].

NAE as a rare skin disorder often represents clinical manifestation of underlying and frequently undiagnosed hepatitis C. The etiology is likely multifactorial, as demonstrated in our patient who had both untreated hepatitis C cirrhosis as well as documented zinc deficiency. This case highlights the importance of clinical recognition of NAE and early skin biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. Additionally, this case provides further cause for the expedient treatment of HCV, particularly in HIV/HCV co-infected patients. High clinical suspicion, physician awareness and early diagnosis play a pivotal role in appropriate management and optimal clinical outcomes.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Qi XS, Rezaee-Zavareh MS, Roohvand F S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Srisuwanwattana P, Vachiramon V. Necrolytic Acral Erythema in Seronegative Hepatitis C. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kapoor R, Johnson RA. Necrolytic acral erythema. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1479-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jakubovic BD, Zipursky JS, Wong N, McCall M, Jakubovic HR, Chien V. Zinc deficiency presenting with necrolytic acral erythema and coma. Am J Med. 2015;128:e3-e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | El-Ghandour TM, Sakr MA, El-Sebai H, El-Gammal TF, El-Sayed MH. Necrolytic acral erythema in Egyptian patients with hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1200-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, Hafez AM, Hiatt KM, Smoller BR, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ko HM, Hernandez-Prera JC, Zhu H, Dikman SH, Sidhu HK, Ward SC, Thung SN. Morphologic features of extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:740138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pernet C, Guillot B, Araka O, Dereure O, Bessis D. Necrolytic acral erythema following hepatitis B vaccination. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1255-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tabibian JH, Gerstenblith MR, Tedford RJ, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Abuav R. Necrolytic acral erythema as a cutaneous marker of hepatitis C: report of two cases and review. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2735-2743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Das A, Kumar P, Gharami RC. Necrolytic Acral Erythema in the Absence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:96-99. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Moneib HA, Salem SA, Darwish MM. Evaluation of zinc level in skin of patients with necrolytic acral erythema. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:476-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fielder LM, Harvey VM, Kishor SI. Necrolytic acral erythema: case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2008;81:355-360. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Najarian DJ, Lefkowitz I, Balfour E, Pappert AS, Rao BK. Zinc deficiency associated with necrolytic acral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:S108-S110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, El-Assar O, Assaf M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:916-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Iyengar S, Chang S, Ho B, Fung MA, Konia TH, Prakash N, Sharon VR. Necrolytic acral erythema masquerading as cellulitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:pii: 13030/qt0dn443r7. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Shumez H, Prasad PVS, Kaviarasan PK, Viswanathan P. Necrolytic acral erythema: high degree of suspicion for diagnosis. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2015;4:435-438. |

| 16. | Shaikh G, Fruchter R, Yagerman S and Franks AG. Successful Treatment of Necrolytic Acral Erythema with Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir. J Clin Dermatol Ther. 2015;3:016. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu YH, Tu ME, Lee CS, Lin YC. Necrolytic acral erythema without hepatitis C infection. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:355-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rahman A, Mulianto I, Julianto I, Oyong P, Mawardi P, Widhiati S. Necrolytic Acral Erythema Case Report. Int J Clin Expl Dermatol. 2017;2:1-4. |

| 19. | Botelho LF, Enokihara MM, Enokihara MY. Necrolytic acral erythema: a rare skin disease associated with hepatitis C virus infection. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:649-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Panda S, Lahiri K. Seronegative necrolytic acral erythema: a distinct clinical subset? Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:259-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pandit VS, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Seronegative necrolytic acral erythema: A report of two cases and literature review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:304-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |