Published online Jan 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i1.127

Peer-review started: September 4, 2018

First decision: October 15, 2018

Revised: December 2, 2018

Accepted: January 3, 2019

Article in press: January 4, 2019

Published online: January 27, 2019

Processing time: 145 Days and 11.1 Hours

Calciphylaxis is a form of vascular calcification more commonly associated with renal disease. While the exact mechanism of calciphylaxis is poorly understood, most cases are due to end stage kidney disease. However, it can also be found in patients without kidney disease and in such cases is termed non-uremic calciphylaxis for which have multiple proposed etiologies.

We describe a case of a thirty-year-old morbidly obese Caucasian female who had a positive history of alcoholic hepatitis and presented with painful calciphylaxis wounds of the abdomen, hips, and thighs. The hypercoagulability panel showed low levels of Protein C and normal Protein S, low Antithrombin III and positive lupus anticoagulant and negative anticardiolipin. Wound biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of non-uremic calciphylaxis in the setting of alcoholic liver disease. The calciphylaxis wounds did not improve when Sodium Thiosulfate was used alone. The patient underwent a series of bedside and surgical debridement. Broad spectrum antibiotics were also used for secondary wound bacterial infections. The patient passed away shortly after due to sepsis and multiorgan failure.

Non-uremic Calciphylaxis can occur in the setting of alcoholic liver disease. The treatment of choice is still unknown.

Core tip: In this case report, we present a patient with alcoholic liver disease and low levels of Protein C who developed calciphylaxis and died shortly after due to complications. The pathogenesis is not completely understood but the disruption of calcium-phosphate-byproduct has been implicated to play a role in the disease process. Liver dysfunction can lead to low levels of coagulation inhibitors specifically Protein C and Protein S. The aim of the medical treatment is to lower the calcium-phosphate-byproduct and decrease the vascular calcification. The use of surgical wound debridement is less established.

- Citation: Sammour YM, Saleh HM, Gad MM, Healey B, Piliang M. Non-uremic calciphylaxis associated with alcoholic hepatitis: A case report. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(1): 127-132

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i1/127.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i1.127

Calciphylaxis is a form of vascular calcification commonly associated with renal disease. Patients diagnosed with calciphylaxis usually face an unfavorable prognosis with most patients dying within 12 mo of diagnosis[1]. Although rare, calciphylaxis has an incidence rate of 35 per 10000 patients in the United States with around 70% of the patients being females and the average age of diagnosis being at 50-70 years[1]. The vascular calcification in calciphylaxis results in ischemic skin lesions that are very painful, treatment resistant, and predisposed to bacterial infections. Most patients with calciphylaxis have a diagnosis of end stage renal disease or other forms of kidney dysfunction including chronic kidney disease, kidney transplantation, or acute kidney injury. Some studies have reported calciphylaxis in patients with normal kidney function, termed non-uremic calciphylaxis[2,3]. Other non-uremic causes of calciphylaxis reported in the literature included primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy, connective tissue disease, and liver disease[1]. As the main clinical manifestation associated with calciphylaxis, the cutaneous lesions can range from minor painful induration to skin necrosis[3].

A thirty-year-old Caucasian female was transferred to our medical center for further management of painful wounds of the abdomen, hips, and thighs. She had a past medical history of alcoholic hepatitis, diagnosed four months earlier with a liver biopsy that showed steatohepatitis and stage 3 fibrosis rather than cirrhosis, and morbid obesity (BMI = 56) status post Roux-en-Y gastric bypass done twelve years ago (unknown pre-surgical BMI). History was negative for diabetes mellitus, kidney dysfunction, autoimmune diseases, hyperparathyroidism or Warfarin intake.

Eight weeks after the onset of alcoholic hepatitis, the patient developed tender erythema on her abdomen, hips, and thighs, which evolved into painful firm subcutaneous nodules.

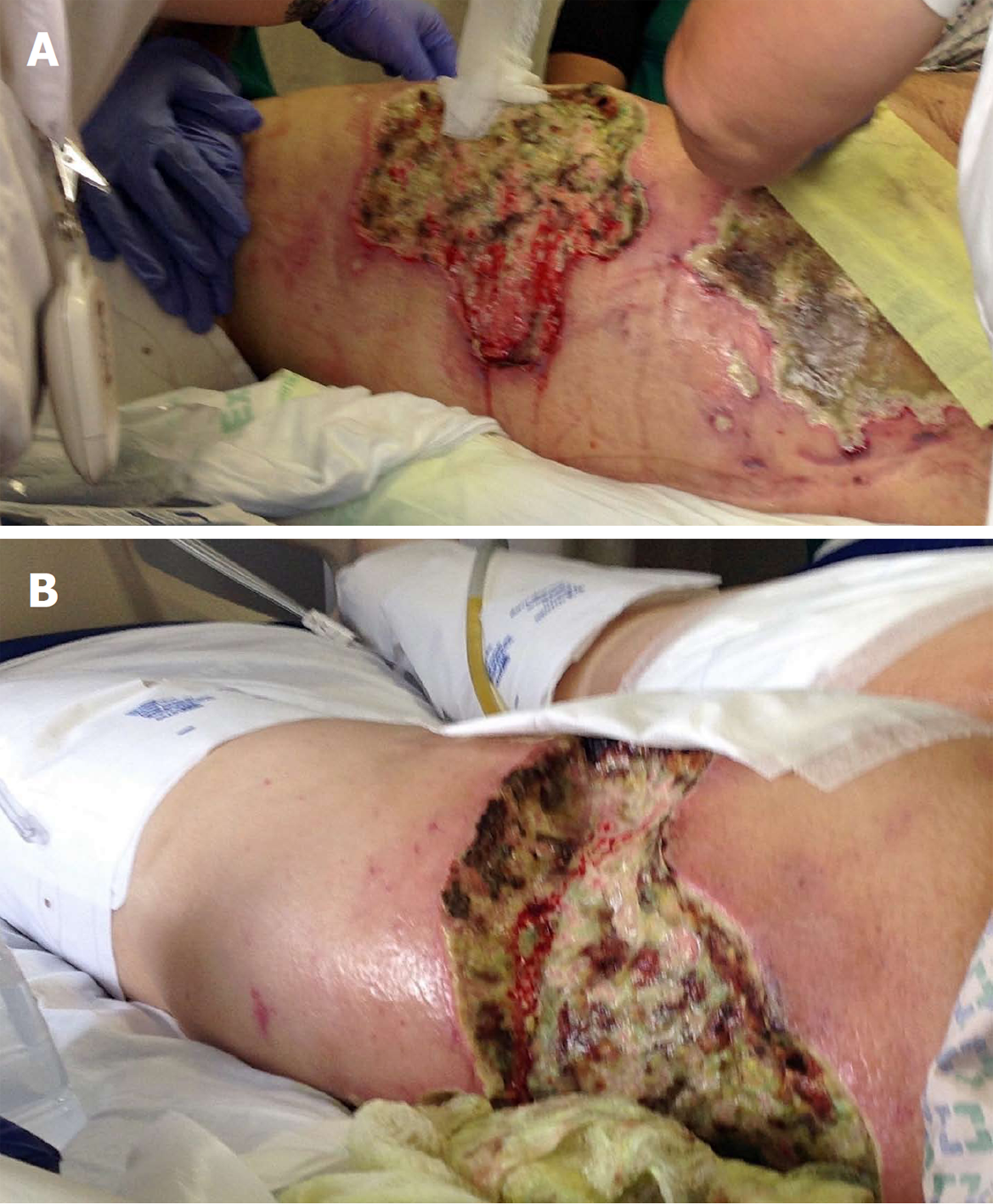

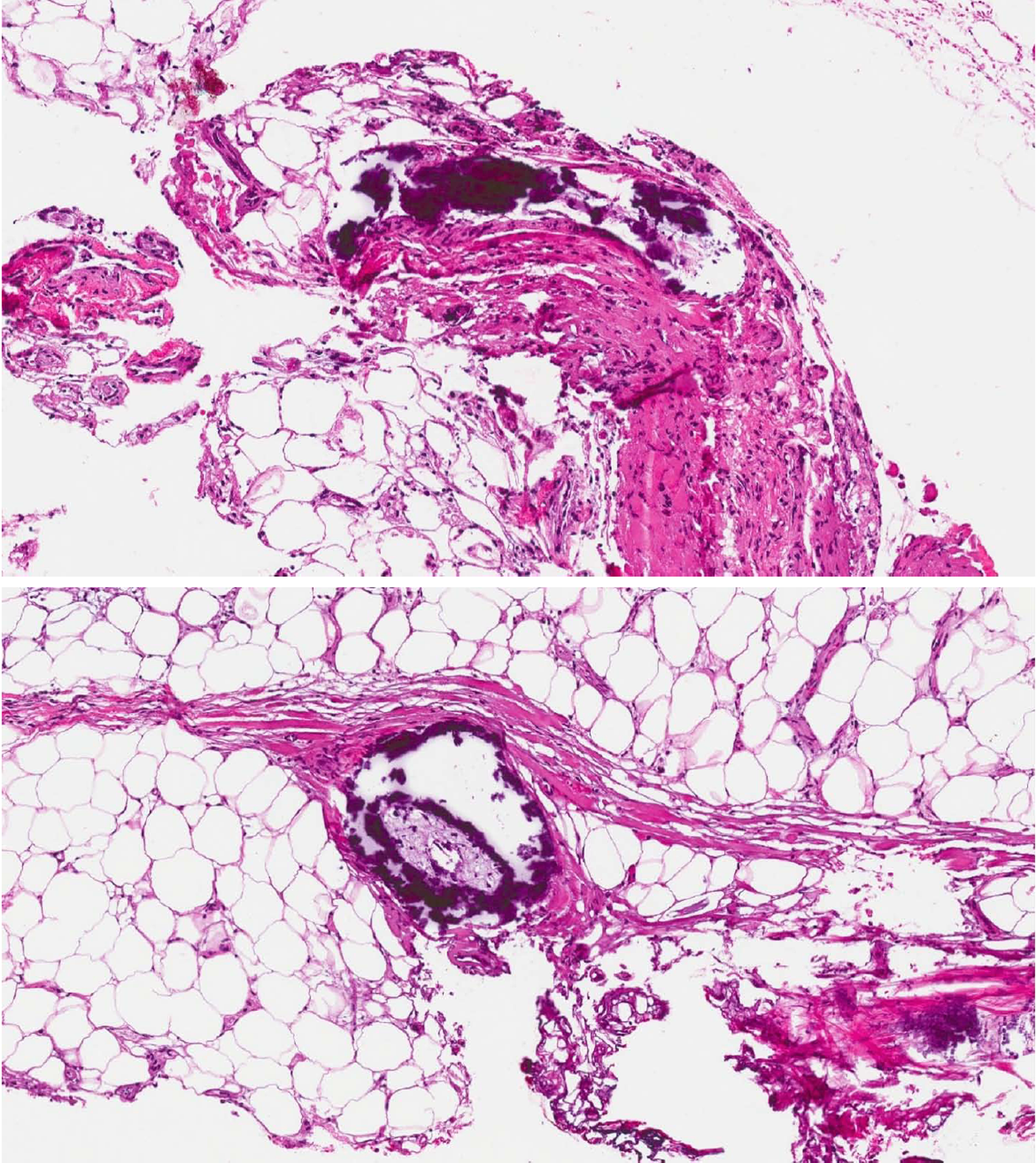

On admission to our hospital, vital signs were notable for temperature 36.7 °C (98.1 °F), blood pressure 98/41 mmHg, pulse 119 bpm, and respiratory rate 20/min. Physical examination showed woody, indurated, exquisitely tender erythematous plaques on the abdomen, hips, and thighs, with central stellate necrotic eschar and purpura (Figure 1A). She also had anterior abdominal wall edema and bilateral lower extremity pitting edema. Laboratory workup was significant for leukocytosis 24 × 109/L , with absolute neutrophil count 21.5 × 109/L , hemoglobin 7.2 g/dL, MCV 87.5 fL, total protein 6.1 g/dL, albumin 1.7 g/dL, AST 56 U/L, ALT 19 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 172 U/L, total bilirubin 1.8 mg/dL, PT 17.7 s, INR 1.6, APTT 37.3, BUN 15 mg/dL, creatinine 1.32 mg/dL, calcium 8.2 mg/dL, phosphorus 3.9 mg/dL, PTH 22 (normal), and 1,25 OH Vit D3 5.8 (low). The hypercoagulability panel showed low levels of Protein C 33 IU/dL (normal: 76-147), low normal levels of protein S 67 IU/dL (normal: 65-135), low antithrombin III levels, positive lupus anticoagulant and negative anticardiolipin. Wound biopsy showed dermal hemorrhage, dermal vascular occlusion, calcium deposition within the walls of large veins and the surrounding adipose tissue (Figure 2). These pathologic findings, correlated clinically, were most consistent with non-uremic calciphylaxis in the setting of alcoholic liver disease.

These pathologic findings, correlated clinically, were most consistent with non-uremic calciphylaxis in the setting of alcoholic liver disease.

Management consisted of sodium thiosulfate infusions, a series of bedside non-excisional and surgical excisional debridement (Figure 1B); in addition to broad spectrum antibiotic treatment for secondary pseudomonas aeruginosa and morganella morganii wound bacterial infections.

The patient was eventually transferred to a regional burn unit for specialized management of the extensive calciphylaxis wounds. Shortly after, the patient passed away due to sepsis and multiorgan failure.

We present a patient with alcoholic liver disease and low normal levels of protein C who developed calciphylaxis and died shortly thereafter from related complications.

The pathogenesis of non-uremic calciphylaxis is not completely understood, but disruption in the calcium-phosphate-byproduct has been implicated to play a role in the disease process[4]. Abnormalities of the Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor-B (RANK, NF-κB), RANK ligand, and osteoprotegerin may be involved. Factors such as liver disease, hyperparathyroidism and corticosteroid use are known to stimulate the expression of RANK ligand and decrease osteoprotegerin, thus activating NF-κB and ultimately leading to osseous mineral loss and extraosseous mineral deposits[5].

Liver dysfunction can lead to low levels of coagulation inhibitors, specifically protein C and S, which can lead to vascular injury[6] as well as thromboembolic manifestations such as deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Another theory behind the link between liver dysfunction and calciphylaxis could be related to Fetuin-A which is a protein synthesized in the liver that acts as a circulating inhibitor of vascular ossification-calcification. Its effects are mediated by ‘‘calciprotein particles’’, which clear the circulating calcium and phosphorus, and therefore selectively inhibit vascular ossification–calcification without affecting the bone mineralization. Another inhibitor of that pathway is the Matrix-GLA-Protein (MGP). Activated MGP, through Vitamin K dependent carboxylation, forms a complex with fetuin-A which inhibits the Bone-Morphogenetic-Protein-2 induced osteogenic differentiation. Thus, liver dysfunction induced vitamin K deficiency can lead to decreased MGP activity and increased vascular ossification-calcification. This mechanism may also explain the association between calciphylaxis and Warfarin-a Vitamin K antagonist[7]. Total uncarboxylated MGP (t-ucMGP) could reflect arterial calcification, with lower values being associated with more widespread calcium deposits[8]. However, its level was not assessed in our patient; its measurement in future studies may be required.

Gastric bypass surgery can also predispose to Vitamin D and Calcium deficiency with secondary hyperparathyroidism due to alterations in the digestive anatomy which could set up a suitable environment for calciphylaxis[9].

The abdomen and thighs are the commonest predilection sites for calciphylaxis lesions due to higher adipose tissue density. The lesions present as indurated plaques or nodules that may have ulcerations and eschar and can be associated with livedo reticularis[10]. A tissue biopsy is essential to confirm the diagnosis[11,12]. Histopathologic changes are similar in both uremic and non-uremic calciphylaxis. Microscopic findings include calcification of dermal vessels and diffuse dermal thrombi. Dermal angioplasia was frequently reported[13]. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like changes were also reported and described as thickened, fragmented and curled elastic fibers[14].

Non-uremic calciphylaxis usually has a poor prognosis with mortality that can reach 50%, most commonly due to sepsis[4]. When calciphylaxis affects proximal areas of the body, such as the abdomen, thighs and buttocks, the mortality rates can reach up to 63%. Distal calciphylaxis, however, is associated with lower mortality, being 23% as reported in one series. The presence of associated ulceration carries a mortality rate of greater than 80%[1,5].

The aim of medical treatment is to reduce the serum calcium-phosphate-byproduct, which can decrease the vascular calcification. Sodium thiosulfate increases the solubility of the calcium deposits and is considered a successful therapy for uremic calciphylaxis[1,2] but our non-uremic patient did not improve when sodium thiosulfate was used alone. Cases of calciphylaxis are usually treated with analgesics, wound care, and proper nutrition. Treatments that have been studied specifically for such cases include sodium thiosulfate, bisphosphonate, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The use of surgical wound debridement is less established and the decision is typically individualized based on the patient characteristics and presentation[1]. No effective treatment is available for non-uremic etiologies of calciphylaxis as the pathology remains unclear[6]. Few cases of non-uremic calciphylaxis were reported with alcoholic liver disease and were treated mainly by serial debridement procedures with wound care and sodium thiosulfate infusions[6,15].

Corticosteroid use was believed to be a predisposing factor for non-uremic calciphylaxis[3], however, Biswas et al[16] reported a case with acute non-uremic calciphylaxis that improved on systemic corticosteroids. Similarly, Elamin et al[17] described another case of calcifying panniculitis that was treated with a 10 d course of oral prednisone resulting in complete healing.

An increasing number of cases of calciphylaxis have been reported in the setting of alcoholic liver disease. The treatment of choice for those patients is still unknown. There is a gap in literature about the role of extensive debridement of the calciphylaxis wounds and whether it can lead to improvement of the outcomes or cause more complications such as sepsis. At this time, further research and interventional studies need to be done to better understand the mechanism of calciphylaxis in those patients, which can help us develop a more effective treatment regimen.

An increasing number of cases of calciphylaxis in the setting of liver failure have recently been reported, but no primary treatment option has been discovered. Surgical debridement and sodium thiosulfate were utilized in this patient, but success was unable to be evaluated as the patient passed from complications before healing could occur. Future studies should expand upon and investigate other therapeutic options for management of non-uremic calciphylaxis in the setting of liver failure.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Farshadpour F, Malnick SDH, Inoue K S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Nigwekar SU, Thadhani R, Brandenburg VM. Calciphylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1704-1714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chan SQ, Wagner I, Vittor GS. Calciphylaxis in the absence of renal failure and hyperparathyroidism in a nonagenarian. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, Hix JK. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hammadah M, Chaturvedi S, Jue J, Buletko AB, Qintar M, Madmani ME, Sharma P. Acral gangrene as a presentation of non-uremic calciphylaxis. Avicenna J Med. 2013;3:109-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sibai H, Ishak RS, Halawi R, Otrock ZK, Salman S, Abu-Alfa A, Kharfan-Dabaja MA. Non-uremic calcific arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma: a previously unreported association. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:e88-e90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shah N, Arshad HMS, Li Y, Silva R. Calciphylaxis in the Setting of Alcoholic Cirrhosis: Case Report and Literature Review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2017;5:2324709617710039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Oliveira TM, Frazão JM. Calciphylaxis: from the disease to the diseased. J Nephrol. 2015;28:531-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Epstein M. Matrix Gla-Protein (MGP) Not Only Inhibits Calcification in Large Arteries But Also May Be Renoprotective: Connecting the Dots. EBioMedicine. 2016;4:16-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Allegretti AS, Nazarian RM, Goverman J, Nigwekar SU. Calciphylaxis: a rare but fatal delayed complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:274-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hesse A, Herber A, Breunig M. Calciphylaxis in a patient without renal failure. JAAPA. 2018;31:28-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kramer ON, Garden BC, Altman I, Braniecki M, Aronson IK. The Signs Aligned: Nonuremic Calciphylaxis. Am J Med. 2017;130:1051-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fergie B, Valecha N, Miller A. A Case of Nonuremic Calciphylaxis in a Caucasian Woman. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2017;2017:6831703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Chen TY, Lehman JS, Gibson LE, Lohse CM, El-Azhary RA. Histopathology of Calciphylaxis: Cohort Study With Clinical Correlations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:795-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nathoo RK, Harb JN, Auerbach J, Guo R, Vincek V, Motaparthi K. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like changes in nonuremic calciphylaxis: Case series and brief review of a helpful diagnostic clue. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:1064-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Akhtar E, Parikh DA, Torok NJ. Calciphylaxis in a Patient With Alcoholic Cirrhosis. ACG Case Rep J. 2015;2:209-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Biswas A, Walsh NM, Tremaine R. A Case of Nonuremic Calciphylaxis Treated Effectively With Systemic Corticosteroids. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:275-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Elamin EM, McDonald AB. Calcifying panniculitis with renal failure: a new management approach. Dermatology. 1996;192:156-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |