Published online Jan 27, 2018. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v10.i1.134

Peer-review started: October 1, 2017

First decision: November 27, 2017

Revised: December 1, 2017

Accepted: December 13, 2017

Article in press: December 13, 2017

Published online: January 27, 2018

Processing time: 121 Days and 17.9 Hours

To examine the effect of center size on survival differences between simultaneous liver kidney transplantation (SLKT) and liver transplantation alone (LTA) in SLKT-listed patients.

The United Network of Organ Sharing database was queried for patients ≥ 18 years of age listed for SLKT between February 2002 and December 2015. Post-transplant survival was evaluated using stratified Cox regression with interaction between transplant type (LTA vs SLKT) and center volume.

During the study period, 393 of 4580 patients (9%) listed for SLKT underwent a LTA. Overall mortality was higher among LTA recipients (180/393, 46%) than SLKT recipients (1107/4187, 26%). The Cox model predicted a significant survival disadvantage for patients receiving LTA vs SLKT [hazard ratio, hazard ratio (HR) = 2.85; 95%CI: 2.21, 3.66; P < 0.001] in centers performing 30 SLKT over the study period. This disadvantage was modestly attenuated as center SLKT volume increased, with a 3% reduction (HR = 0.97; 95%CI: 0.95, 0.99; P = 0.010) for every 10 SLKs performed.

In conclusion, LTA is associated with increased mortality among patients listed for SLKT. This difference is modestly attenuated at more experienced centers and may explain inconsistencies between smaller-center and larger registry-wide studies comparing SLKT and LTA outcomes.

Core tip: Simultaneous liver kidney transplantation (SLKT) has doubled from 2002-2013. We studied the effect of transplant center volume on survival outcomes. There was a significant survival disadvantage for liver transplant alone (LTA) vs SLKT in centers performing 30 SLKT over the study period, although this disadvantage was slightly diminished with increasing center SLKT volume. Therefore, centers with higher transplant volume have a lesser mortality difference in LTA compared to SLKT than those centers with smaller volume.

- Citation: Modi RM, Tumin D, Kruger AJ, Beal EW, Hayes Jr D, Hanje J, Michaels AJ, Washburn K, Conteh LF, Black SM, Mumtaz K. Effect of transplant center volume on post-transplant survival in patients listed for simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation. World J Hepatol 2018; 10(1): 134-141

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v10/i1/134.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v10.i1.134

The debate over outcomes of simultaneous liver kidney transplantation (SLKT) vs liver transplantation alone (LTA) has intensified since the introduction of Model for End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) into the allocation system for donor livers. An unintentional byproduct of the implementation of the MELD score was an increase in the number of SLKT. From 2002 to 2013, the percentage of SLKT has increased from 4% to 8% of all liver transplants[1], contributing to a shortage of deceased donor kidney grafts for patients on the waitlist for deceased donor kidney transplantation. Since 2007, four guidelines have been proposed for SLKT listing by various societies, including one by the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN) and a more recent consensus report by Davis et al[2], Eason et al[3] and Nadim et al[4]. The current recommendations for SLKT include one of the following: (1) Renal replacement therapy (eGFR of 30 mL/min or less) for a minimum of 4-8 wk; (2) proteinuria > 2 g/d; and (3) biopsy-proven interstitial fibrosis or glomerulosclerosis[1,4].

A recent survey studied variations in practice among liver transplant centers in the United States and found that SLKT listing was influenced by center-size rather than aforementioned guidelines[5]. Of the 88 transplant centers that were surveyed, centers that performed greater than 10 SLKT annually were more likely to use lenient dialysis duration (4 wk vs 6 or 8 wk). This variability in center practice may contribute to the significant inconsistencies among numerous studies comparing the outcomes of SLKT vs LTA, including patient and graft survival[6-9]. A 2015 study using the United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) database showed LTA outcomes were inferior to SLKT in all patients listed for SLKT[10], while a 2016 re-analysis of UNOS data found the difference in survival was not statistically significant[11]. Similar to large registry analyses, single-center studies have reported mixed findings on the difference in mortality between SLKT and LTA. Many earlier studies showed no difference between outcomes comparing SLKT to LTA[12-14]; however, a recent single-center study found improved outcomes with SLKT vs LTA[15].

Studies have also suggested that larger centers attain more favorable transplant outcomes, even when involving higher-risk recipients or donors[16,17]. Therefore, the disadvantage of performing LTA in patients listed for SLKT (as reported by some prior studies) could be attenuated at the most experienced programs. However, the effect of transplant center volume on outcome differences between SLKT vs LTA has not been evaluated. This study examines the transplant center volume as a potential moderating factor in patients initially listed for SLKT. We hypothesized that the survival disadvantage associated with LTA (compared to SLKT) in patients listed for SLKT would be smaller in more experienced centers performing a greater number of SLKT.

Data were obtained from the OPTN Standard Transplant Analysis and Research Database[18]. The institutional review board at Nationwide Children’s Hospital exempted the study from review (IRB16-01193). The UNOS/OPTN database was queried for all patients ≥ 18 years of age who were listed for SLKT between February 2002 and December 2015 (post-MELD allocation era), and received either SLKT or LTA. Exclusion criteria were prior transplantation, donation from a non-heart beating donor, living donor liver transplant and receipt of a split liver transplant. The primary outcome was patient survival after LTA vs SLKT, among patients listed for SLKT.

Descriptive characteristics of patients meeting inclusion criteria were compared according to the type of transplant (LTA vs SLKT) using unpaired t-tests for continuous data and χ2 tests for categorical data. Among patients with known survival time, survival was compared according to transplant type using Kaplan-Meier curves with a log-rank test. Supplemental descriptive statistics and Kaplan-Meier survival curves included stratification of the study sample by tertiles of center SLKT volume, described below. Cases with complete data on covariates were entered in a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, where the baseline hazard was stratified across transplant centers. In this stratified Cox model, hazard ratios (HRs) represented differences in survival among patients belonging to the same stratum, meaning differences in survival between patients transplanted at the same center. Center volume was primarily defined as the total number of SLKT performed by each center over the study period (2/2002-12/2015). In supplemental analyses, we demonstrate the robustness of our results to using the total number of liver transplants over the study period, or the annual number of SLKT at a given center, as alternative measures of center volume.

In the Cox model, type of transplant (LTA vs SLKT) was interacted with continuous center volume to allow the HR of transplant type (i.e., estimated difference in survival between LTA and SLKT) to vary according to center volume[19]. The main effect of total center volume was not estimated in the stratified Cox model, as patients transplanted at the same center shared the same value for overall center volume. For model presentation, volume was centered at 30 total SLKT over the study period, approximately corresponding to the median center in the analytic sample, and divided by 10 (i.e., a value of 0 indicated 30 SLKT performed over the study period; a value of 1 indicated 40 SLKT performed, and so on). Therefore, the main effect (HR) of transplant type described the difference in survival between LTA and SLKT for a center performing 30 SLKT; while the interaction between transplant type and center volume described how this difference was reduced (if the interaction HR was < 1) in more experienced centers.

Covariates in the analysis included recipient age, gender, race, etiology of liver disease, diabetes, dialysis, body mass index (BMI), serum creatinine, serum bilirubin, serum albumin, international normalized ratio (INR), Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) according to Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation. Hepatic encephalopathy on the wait list, year of transplantation, and liver allograft cold ischemia time were also included. Analyses were performed using Stata/IC 13.1 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

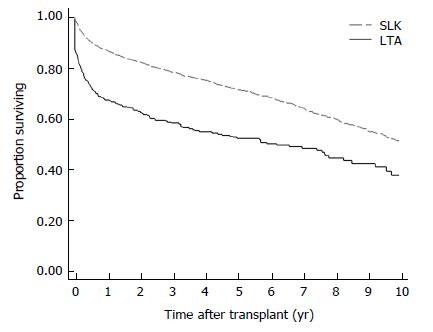

The analytic sample included 4580 patients listed for SLKT, of whom 393 (9%) received LTA and 4187 (91%) received SLKT. Among these patients, 4573 had known survival time and 4257 had complete data on covariates in the multivariable analysis. There were 121 transplant centers represented in this sample, with a median SLKT volume of 33 over the entire study period [range: 1-278; interquartile range (IQR): 15-62]. The median annual SLKT volume was 3 (range: 0-21; IQR: 2-6). The median center liver transplant volume was 561 over the entire study period (range: 4-2696; IQR: 214-986). Overall mortality occurred in 28% of cases (1287/4580). The Kaplan-Meier plot (Figure 1) and log-rank test (P < 0.001) demonstrate worse survival of LTA vs SLKT recipients among patients initially listed for SLKT. Actuarial 1, 3 and 5 year survival rates among the LTA and SLKT groups were 68% vs 87%, 59% vs 79%, and 53% vs 72%, respectively. Other characteristics are compared between the 2 types of transplant in Table 1.

| Variable1 | Cases missing data | Received LTA (n = 393) | Received SLK (n = 4187) | P value2 |

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | Mean (SD) or n (%) | |||

| Transplant center SLKT volume | 0 | 107 (± 83) | 91 (± 66) | < 0.001 |

| Transplant center LTA volume3 | 0 | 1187 (628) | 1111 (627) | 0.024 |

| Age (yr) | 0 | 54.2 (± 9.7) | 54.8 (± 9.6) | 0.279 |

| Male | 0 | 234 (60%) | 2778 (66%) | 0.007 |

| Race | 0 | 0.079 | ||

| White | 270 (69%) | 2648 (63%) | ||

| Black | 47 (12%) | 639 (15%) | ||

| Other | 76 (19%) | 900 (22%) | ||

| Etiology of liver disease | 0 | 0.004 | ||

| Viral | 114 (29%) | 1182 (28%) | ||

| Cryptogenic | 34 (9%) | 330 (8%) | ||

| Autoimmune | 31 (8%) | 197 (5%) | ||

| NASH | 43 (11%) | 454 (11%) | ||

| Alcoholic | 89 (23%) | 982 (23%) | ||

| HCC | 28 (7%) | 376 (9%) | ||

| AHN | 16 (4%) | 85 (2%) | ||

| Other | 38 (10%) | 581 (14%) | ||

| Diabetes | 65 | 123 (32%) | 1665 (40%) | 0.001 |

| Dialysis | 0 | 109 (28%) | 1963 (47%) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 5 | 29.0 (± 5.9) | 28.3 (± 5.9) | 0.044 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 5 | 2.8 (± 2.1) | 3.8 (± 2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 5 | 8.2 (± 11.7) | 5.7 (± 9.2) | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 6 | 3.0 (± 0.8) | 3.0 (± 0.7) | 0.074 |

| INR | 5 | 1.9 (± 1.4) | 1.6 (± 0.7) | < 0.001 |

| MELD score | 16 | 25.6 (± 10.5) | 25.2 (± 8.7) | 0.445 |

| eGFR | 5 | 37.5 (± 27.2) | 26.8 (± 22.4) | < 0.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy on wait list | 31 | 308 (79%) | 2882 (69%) | < 0.001 |

| Liver allograft cold ischemia time | 213 | 6.8 (± 2.6) | 6.8 (± 3.5) | 0.706 |

| Yr of transplant | 0 | 2009 (4) | 2010 (4) | < 0.001 |

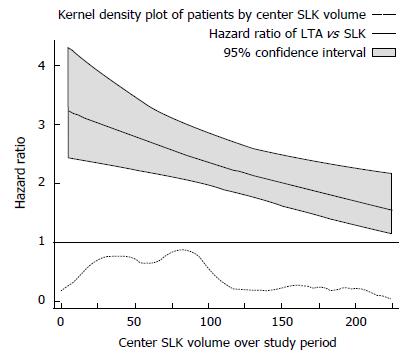

The main multivariable stratified Cox model is presented in Table 2. At a center performing 30 SLKT over the study period, the model estimates a significant survival disadvantage associated with receiving LTA vs SLKT (HR = 2.85; 95%CI: 2.21-3.66; P < 0.001). However, a statistically significant modification of this difference was observed as total center SLKT volume increased (interaction HR = 0.97; 95%CI: 0.95-0.99; P = 0.010), meaning that the survival disadvantage of LTA vs SLKT was attenuated by about 3% for each additional 10 SLKTs performed by a given center over the study period. Based on this model, estimated differences in survival (HR) between LTA and SLKT are plotted across center SLKT volume in Figure 2. For example, at a center performing a total of 15 SLKT over the study period (approximately the 25th percentile of centers), the HR of LTA compared to SLKT was 2.98 (95%CI: 2.26-3.92; P < 0.001); while at a center performing a total of 60 SLKT over the study period (approximately the 75th percentile of centers), this HR was reduced to 2.61 (95%CI: 2.11-3.23; P < 0.001).

| Variable1 | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Transplant received | |||

| SLK | ref. | ||

| LTA | 2.85 | (2.21, 3.66) | < 0.001 |

| Transplant center SLK volume2 | |||

| Interaction with receiving LTA vs SLK | 0.97 | (0.95, 0.99) | 0.010 |

| Age (yr) | 1.01 | (1.01, 1.02) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 1.08 | (0.94, 1.24) | 0.285 |

| Race | |||

| White | ref. | ||

| Black | 1.17 | (0.98, 1.39) | 0.089 |

| Other | 0.79 | (0.66, 0.94) | 0.007 |

| Etiology of liver disease | |||

| Viral | ref. | ||

| Cryptogenic | 0.77 | (0.61, 0.98) | 0.033 |

| Autoimmune | 0.57 | (0.41, 0.79) | 0.001 |

| NASH | 0.79 | (0.63, 1.01) | 0.060 |

| Alcoholic | 0.65 | (0.54, 0.77) | < 0.001 |

| HCC | 1.04 | (0.83, 1.30) | 0.721 |

| AHN | 1.10 | (0.75, 1.63) | 0.621 |

| Other | 0.77 | (0.62, 0.97) | 0.024 |

| Diabetes | 1.23 | (1.08, 1.40) | 0.002 |

| Dialysis | 1.41 | (1.19, 1.67) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.98 | (0.97, 0.99) | 0.003 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.97 | (0.93, 1.01) | 0.092 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.00 | (0.98, 1.01) | 0.394 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 0.88 | (0.81, 0.96) | 0.004 |

| INR | 0.92 | (0.81, 1.05) | 0.224 |

| MELD score | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.02) | 0.661 |

| eGFR | 1.00 | (1.00, 1.01) | 0.622 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy on wait list | 1.10 | (0.94, 1.28) | 0.221 |

| Liver allograft cold ischemia time | 1.00 | (0.98, 1.02) | 0.811 |

| Year of transplant | 0.98 | (0.96, 1.00) | 0.107 |

Our findings were consistent when using total liver transplant center volume as a measure of center expertise; with a survival disadvantage for LTA vs SLKT at centers performing approximately the median volume (500) of liver transplants over the study period (HR = 2.89; 95%CI: 2.18-3.83; P < 0.001). This disadvantage was diminished at centers that performed more liver transplants over the study period (interaction HR = 0.97; 95%CI: 0.94-1.00; P = 0.027). Despite this statistically significant interaction, a survival disadvantage of LTA vs SLKT was predicted for centers of all but the highest total liver transplant volumes (Supplemental Figure 1). Finally, the findings were robust when using a measure of annual, rather than total, SLKT volume (Supplemental Table 1; Supplemental Figure 2). Of note, the main effect of annual center volume in the stratified Cox model was not statistically significant (Supplemental Table 1: HR = 1.00; 95%CI: 0.98-1.02; P = 0.940). Therefore, year-to-year fluctuations in SLKT volume within a single center were not associated with survival outcomes of patients originally listed for SLKT.

Supplemental descriptive statistics according to center SLKT volume tertile are presented in Supplemental Table 2. A log-rank test found no difference in survival among patients in the study cohort according to tertile of center SLKT volume over the study period (P = 0.28; Supplemental Figure 3). However, there was marginally less mortality among patients who underwent LTA at larger centers, as illustrated in Supplemental Figure 4 (P = 0.05). The smaller survival difference between SLKT vs LTA in larger centers may be partially explained by a survival advantage of total center volume for SLKT-listed patients who received LTA.

Using a large national registry we found that center volume influenced the disparity in outcomes between LTA and SLKT, among patients initially listed for SLKT. More experienced centers achieved a smaller difference in mortality between the two types of transplant. With limited data investigating how center volume influences outcomes of multi-visceral organ transplantation, our findings suggest a survival disadvantage for LTA vs SLKT recipients at low volume centers, which is partially attenuated at higher volume centers. This influence of center volume on the effect of undergoing LTA after being listed for SLKT may also provide some insight into inconsistencies reported in literature on patients listed for SLKT.

While our study showed center volume influenced survival differences between SLKT and LTA, it is important to compare these findings to existing literature investigating this difference. A recent single-center study found improved overall 1- and 5- year survival rates among SLKT recipients compared to LTA recipients (92.3% and 81.6% vs 73.3% and 64.3% respectively)[15]. On the other hand, a previous single-center study at a larger center found no 1-year survival advantage in LTA vs SLKT recipients[13]. Difference in the size of these centers (according to Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients data from January 2013-June 2015) are consistent with our findings that the survival disadvantage of LTA among patients listed for SLKT is attenuated at larger centers.

Large database studies have also reached incongruous conclusions. Hmoud et al[10] recently used the UNOS database to show that LTA outcomes were inferior to SLKT in SLKT-listed patients. However, when comparing SLKT recipients to a propensity-matched subgroup of all liver transplant recipients, Sharma et al[11] demonstrated that differences in survival were not clinically significant. By using Cox regression stratified on the transplant center, we attempted to analyze comparable LTA and SLKT recipients (i.e., clusters of recipients transplanted at the same center), while preserving the constraint that all LTA patients must have been listed for SLKT. While our results show smaller differences in survival between LTA and SLKT at more experienced centers, there was no expertise threshold above which LTA outcomes were equal to SLKT outcomes in patients initially listed for SLKT.

With increasing rates of SLKT being performed, it is important to consider center expertise as variable influencing transplant outcomes. Existing literature has explored independent influences of center volume on liver transplant outcomes. A 2011 study indicated that the increased center volume led to reduced allograft rejection and improved recipient survival[16]. More recently, 5130 liver transplants were stratified by number of transplants performed, and transplantation at a higher volume center was associated with lower mortality, length of stay, and costs compared to centers performing fewer transplants[17].

We demonstrated a tendency to perform fewer LTA in patients listed for SLKT at larger centers, which could be due to multiple reasons. Compared to smaller centers, larger transplant centers have distinct advantages including a dedicated and experienced organ procurement team and adequate organ transportation and storage facility. Additionally, the increased number of transplants performed may result in a technical advantage and increased experience to adequately address intra-operative and post-procedural complications. The combination of adequate ancillary staff, resources, and patient referrals enable increased SLKT listing and subsequent transplantation at large programs. It is possible that higher LTA mortality at smaller centers was related to patients who could not wait for multi-organ transplantation; and that high volume centers are able to better manage this patient population. These non-measurable factors may influence center specific outcomes, as programs are dependent on outcomes measures to continue to expand their transplant practice.

With the rise in SLKT, there has been an unintentional reduction in available kidney donors candidates afflicted with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Due to this concomitant single organ donation, experts have suggested stricter criteria for the allocation of two allografts, especially considering limited access to kidneys compared to livers[6,13,20,21]. Recently, Cheng et al[22] outlined an important distinction of utility vs urgency based practice, where each SLKT resulted in a reduction of 1-year allograft lifespan to provide sicker patient populations access to dual organ transplantation. Our results indicate that patients listed for SLKT have worse outcomes when only receiving a liver allograft, indicating further discussion regarding standardizing national guidelines for SLKT listing is required. We recognize there is a real need for dual organ transplantation as the OPTN recently proposed a change in SLKT guidelines; however, improving the current allocation system between the ESRD and SLKT population is also needed[23-25]. Our study suggests when implementing national change, patients listed for SLKT should be evaluated with stricter criteria to ensure individuals listed for SLKT obtain both organs.

The current analysis is limited in several aspects, including the potential exclusion of confounding variables, missing data, and data entry errors. We were unable to assess important variables such as the duration of dialysis or renal impairment, biopsy proven renal interstitial fibrosis, or proteinuria. Although these factors influence the SLKT listing process, our focus was on post-transplant mortality differences between LTA and SLKT groups. Additionally, patients who received a LTA rather than SLKT may have had worsening clinical status, which could inherently bias estimating the difference in survival between the two procedures. Finally, while we used center volume as a measure of expertise, it is important to note it was not possible to assess peri-operative and post-operative management of patients as well as long-term medical management.

In summary, we demonstrated that centers with higher transplant volume achieve smaller difference in mortality with LTA as compared to SLKT among patients initially listed for SLKT. This finding may help reconcile controversy in the literature regarding center size and outcomes of LTA. These findings further demonstrate the need for standardization of SLKT listing guidelines.

There has been an increase in the number of simultaneous liver kidney transplantation (SLKT) performed over the past decade. Recently, it has been noted that SLKT listing was influenced by center-size rather than by guidelines. Inconsistent outcomes of SLKT vs liver transplantation alone (LTA) have been reported.

The effect of transplant center volume on outcome differences between SLKT vs LTA has not been evaluated. As such, the authors examined transplant center volume as a potential moderating factor in patients initially listed for SLKT.

The authors hypothesized that the survival disadvantage associated with LTA (compared to SLKT) in patients listed for SLKT would be smaller in more experienced centers performing a greater number of SLKT.

The United Network of Organ Sharing database was queried for patients ≥ 18 years of age listed for SLKT between February 2002 and December 2015. Post-transplant survival was evaluated using stratified Cox regression with interaction between transplant type (LTA vs SLKT) and center volume.

Overall, 393 of 4580 patients (9%) listed for SLKT underwent LTA. Mortality was higher among LTA recipients (180/393, 46%) than SLKT recipients (1107/4187, 26%). The Cox model predicted a significant survival disadvantage for patients receiving LTA vs SLKT (HR: 2.85; 95%CI: 2.21-3.66) in centers performing 30 SLKT over the study period. This disadvantage was modestly attenuated as center SLKT volume increased, with a 3% reduction (HR: 0.97; 95%CI: 0.95-0.99) for every 10 SLKs performed.

LTA is associated with increased mortality among patients listed for SLKT. This difference is modestly attenuated at more experienced centers and may explain inconsistencies between smaller-center and larger registry-wide studies comparing SLKT and LTA outcomes.

The findings of this study may help to reconcile the current controversy regarding center size and outcomes of LTA. Future research should focus on the apparent need for standardization of SLKT listing guidelines.

The data reported here have been supplied by the United Network for Organ Sharing as the contractor for the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the United States Government.

Manuscript source: Invited Manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fava G, Guo JS, Lopez V, Tao R S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Saxena V, Lai JC. Kidney Failure and Liver Allocation: Current Practices and Potential Improvements. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22:391-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Davis CL, Feng S, Sung R, Wong F, Goodrich NP, Melton LB, Reddy KR, Guidinger MK, Wilkinson A, Lake J. Simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation: evaluation to decision making. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1702-1709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Eason JD, Gonwa TA, Davis CL, Sung RS, Gerber D, Bloom RD. Proceedings of Consensus Conference on Simultaneous Liver Kidney Transplantation (SLK). Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2243-2251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nadim MK, Sung RS, Davis CL, Andreoni KA, Biggins SW, Danovitch GM, Feng S, Friedewald JJ, Hong JC, Kellum JA. Simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation summit: current state and future directions. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:2901-2908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nadim MK, Davis CL, Sung R, Kellum JA, Genyk YS. Simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation: a survey of US transplant centers. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:3119-3127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Locke JE, Warren DS, Singer AL, Segev DL, Simpkins CE, Maley WR, Montgomery RA, Danovitch G, Cameron AM. Declining outcomes in simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation in the MELD era: ineffective usage of renal allografts. Transplantation. 2008;85:935-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fong TL, Khemichian S, Shah T, Hutchinson IV, Cho YW. Combined liver-kidney transplantation is preferable to liver transplant alone for cirrhotic patients with renal failure. Transplantation. 2012;94:411-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jeyarajah DR, Gonwa TA, McBride M, Testa G, Abbasoglu O, Husberg BS, Levy MF, Goldstein RM, Klintmalm GB. Hepatorenal syndrome: combined liver kidney transplants versus isolated liver transplant. Transplantation. 1997;64:1760-1765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Martin EF, Huang J, Xiang Q, Klein JP, Bajaj J, Saeian K. Recipient survival and graft survival are not diminished by simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation: an analysis of the united network for organ sharing database. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:914-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hmoud B, Kuo YF, Wiesner RH, Singal AK. Outcomes of liver transplantation alone after listing for simultaneous kidney: comparison to simultaneous liver kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99:823-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sharma P, Shu X, Schaubel DE, Sung RS, Magee JC. Propensity score-based survival benefit of simultaneous liver-kidney transplant over liver transplant alone for recipients with pretransplant renal dysfunction. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:71-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Catalano G, Tandoi F, Mazza E, Simonato F, Tognarelli G, Biancone L, Lupo F, Romagnoli R, Salizzoni M. Simultaneous Liver-Kidney Transplantation in Adults: A Single-center Experience Comparing Results With Isolated Liver Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:2156-2158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ruiz R, Kunitake H, Wilkinson AH, Danovitch GM, Farmer DG, Ghobrial RM, Yersiz H, Hiatt JR, Busuttil RW. Long-term analysis of combined liver and kidney transplantation at a single center. Arch Surg. 2006;141:735-741; discussion 741-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mehrabi A, Fonouni H, Ayoub E, Rahbari NN, Müller SA, Morath Ch, Seckinger J, Sadeghi M, Golriz M, Esmaeilzadeh M, Hillebrand N, Weitz J, Zeier M, Büchler MW, Schmidt J, Schmied BM. A single center experience of combined liver kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2009;23 Suppl 21:102-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Doyle MB, Subramanian V, Vachharajani N, Maynard E, Shenoy S, Wellen JR, Lin Y, Chapman WC. Results of Simultaneous Liver and Kidney Transplantation: A Single-Center Review. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:193-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ozhathil DK, Li YF, Smith JK, Tseng JF, Saidi RF, Bozorgzadeh A, Shah SA. Impact of center volume on outcomes of increased-risk liver transplants. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:1191-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Macomber CW, Shaw JJ, Santry H, Saidi RF, Jabbour N, Tseng JF, Bozorgzadeh A, Shah SA. Centre volume and resource consumption in liver transplantation. HPB (Oxford). 2012;14:554-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | U.S. Department of Human and Health Services. United network for organ sharing / organ procurement and transplantation network standard transplant analysis and research database. 2016;. |

| 19. | Hayes D, Hartwig MG, Tobias JD, Tumin D. Lung Transplant Center Volume Ameliorates Adverse Influence of Prolonged Ischemic Time on Mortality. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:218-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sharma P, Goodrich NP, Zhang M, Guidinger MK, Schaubel DE, Merion RM. Short-term pretransplant renal replacement therapy and renal nonrecovery after liver transplantation alone. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1135-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chang Y, Gallon L, Shetty K, Chang Y, Jay C, Levitsky J, Ho B, Baker T, Ladner D, Friedewald J. Simulation modeling of the impact of proposed new simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation policies. Transplantation. 2015;99:424-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cheng X SM, Kim W, Tan J. Utility in treating renal failure in end-stage liver disease with simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2016;. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Unos/optn kidney transplantation committee. Simultaneous liver kidney (slk) allocation policy; 2015. . |

| 24. | Formica RN, Aeder M, Boyle G, Kucheryavaya A, Stewart D, Hirose R, Mulligan D. Simultaneous Liver-Kidney Allocation Policy: A Proposal to Optimize Appropriate Utilization of Scarce Resources. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:758-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wadei HM, Gonwa TA, Taner CB. Simultaneous Liver Kidney Transplant (SLK) Allocation Policy Change Proposal: Is It Really a Smart Move? Am J Transplant. 2016;16:2763-2764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |