Published online Mar 26, 2016. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v8.i3.73

Peer-review started: September 6, 2015

First decision: November 11, 2015

Revised: December 24, 2015

Accepted: January 27, 2016

Article in press: January 29, 2016

Published online: March 26, 2016

Processing time: 205 Days and 2.2 Hours

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are currently being investigated for use in a wide variety of clinical applications. For most of these applications, systemic delivery of the cells is preferred. However, this requires the homing and migration of MSCs to a target tissue. Although MSC homing has been described, this process does not appear to be highly efficacious because only a few cells reach the target tissue and remain there after systemic administration. This has been ascribed to low expression levels of homing molecules, the loss of expression of such molecules during expansion, and the heterogeneity of MSCs in cultures and MSC culture protocols. To overcome these limitations, different methods to improve the homing capacity of MSCs have been examined. Here, we review the current understanding of MSC homing, with a particular focus on homing to bone marrow. In addition, we summarize the strategies that have been developed to improve this process. A better understanding of MSC biology, MSC migration and homing mechanisms will allow us to prepare MSCs with optimal homing capacities. The efficacy of therapeutic applications is dependent on efficient delivery of the cells and can, therefore, only benefit from better insights into the homing mechanisms.

Core tip: Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are currently under investigation for use in a variety of clinical applications. In most studies, MSCs are administered systemically. This requires efficient homing and migration of the MSCs to a target tissue. However, the homing mechanisms of MSCs are not completely understood. Moreover, the in vivo homing and migration of MSCs does not appear to be highly efficient. Therefore, different methods have been investigated to improve homing. Here, we will review the current knowledge of bone marrow homing of MSCs, as well as the different strategies that might improve the homing capacity of these stem cells.

- Citation: De Becker A, Riet IV. Homing and migration of mesenchymal stromal cells: How to improve the efficacy of cell therapy? World J Stem Cells 2016; 8(3): 73-87

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v8/i3/73.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v8.i3.73

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are non-haematopoietic cells that were first derived from the bone marrow and described approximately 40 years ago by Friedenstein et al[1]. In 2006, the International Society for Cell Therapy defined the minimal criteria to define human MSCs. They must adhere to plastic in culture and differentiate into osteocytes, chondrocytes and adipocytes. Additionally they must express CD105, CD90 and CD73 and lack expression of CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, CD79alpha or CD19, and HLA-DR surface molecules[2].

There is great interest in using these cells in a wide variety of clinical domains, such as Neurology, Orthopaedics, Cardiology and Haematology[3-6]. This interest arises from the following MSC characteristics: They have immunomodulatory capacities, they are multipotent and are thus possible effectors for tissue regeneration, and they tend to migrate to sites of tissue injury/inflammation[7-11]. Additionally MSCs might escape immune recognition, although conflicting observations about this particular phenotype have been published. MSCs do not express MHC class II antigens, but the expression of these molecules can be upregulated after exposure to inflammatory cytokines or during MSC differentiation[12]. The data from animal studies suggest that MSCs can elicit allogeneic immune responses and be rejected[13-16]. On the other hand, there is also a report of MSCs that overcame this allogeneic immune response due to their immunomodulatory capacities[17]. von Bahr et al[18] addressed this issue and published follow-up data of patients treated with MSCs, showing that there was no correlation between the MSC source (donor-derived or third party) and the patients’ response to the MSC treatment. The clinical applications of these cells have been extensively studied in Orthopaedics, where MSCs are used to repair large bone defects, and in Haematology for the treatment of graft-vs-host disease and support for the engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells[4,6,19]. In recent years, MSCs have been studied as vehicles to deliver anti-cancer treatments because there is evidence that MSCs home to tumour sites. They can be induced to express anti-cancer proteins [e.g., interleukin (IL) 2], to produce pro-drug activating enzymes, which ensures that the active drug will only be localized in the tumour, or to deliver oncolytic viruses[20-23]. For these applications, the homing and persistence of MSCs in the target tissue are desirable[24].

When MSCs are used in clinical applications, different modes of administration are possible: Systemic administration [intravenous (IV) or intra-arterial (IA) injection] or local administration [intracoronary (IC) injection or direct injection into the tissue of interest]. Of these different options, IV injection is the most widely used because it is minimally invasive, the infusions can be readily repeated and the cells will remain close to the oxygen- and nutrient-rich vasculature after extravasation into the target tissue[25]. However, after IV injection, the cells appear to be trapped in the lungs, and thus efficient homing to the target tissues might be compromised. IA administration requires an invasive procedure that has a higher risk of complications than IV. Although IA injections might improve tissue-specific homing compared to IV, there is a concern that microthrombi might occur as a result of trapping large MSCs in the microvasculature. One example is the concern regarding IC injections of MSCs to treat myocardial infarction[26]. Similar concerns have been raised in studies that used MSCs to treat stroke[27,28]. A true local injection of MSCs might require a surgical intervention, such as that used in the repair of bone defects. In this setting, the MSCs are immediately delivered to the target tissue; however, the cells’ survival might be compromised due to a lack of oxygen or nutrients[25]. Currently, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is performed via an IV infusion. Intra-bone marrow transplantation is a more complex procedure, but evidence from an animal model suggests that this might improve the outcome of the treatment[29]. Finally, some animal models of systemic administration, such as intracardiac injection, cannot readily be performed in patients.

The systemic infusion of cells for therapeutic applications implies and requires efficient migration and homing to the target site. Although there is ample evidence of MSC homing, this process appears to be inefficient because only a small percentage of the systemically administered MSCs actually reach the target tissue[30]. The mechanisms by which the MSCs migrate and home are not yet clearly understood.

Currently, in Haematology, MSCs are mainly being tested for their ability to control graft-vs-host disease and to support haematopoiesis after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Chemo- and radio-therapy can damage the haematopoietic niche. MSCs are part of this niche and secrete a number of haematopoietic growth factors. To facilitate the engraftment of haematopoietic stem cells and stimulate blood formation, the MSCs should successfully home to and persist in the bone marrow[31]. In this review, we discuss current knowledge about MSC homing, specifically focusing on bone marrow homing (based on both in vitro and in vivo data), and we review the efforts that different groups have undertaken to improve the homing efficiency of these cells.

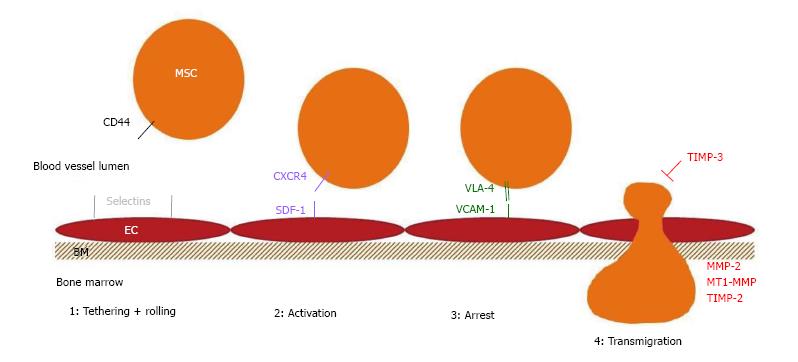

The exact mechanisms used by MSCs to migrate and home to tissues have not been fully elucidated. It is generally assumed that these stem cells follow the same steps that were described for leukocyte homing. In the first step, the cells come into contact with the endothelium by tethering and rolling, resulting in a deceleration of the cells in the blood flow. In the second step, the cells are activated by G-protein-coupled receptors, followed by integrin-mediated, activation-dependent arrest in the third step. Finally, in the fourth step, the cells transmigrate through the endothelium and the underlying basement membrane[32].

The first studies addressing MSC homing examined the origin of the bone marrow MSCs after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Those groups all concluded that the haematopoietic cells were provided by the donor, but the stromal cells were provided by the recipient[33-35]. However, in these studies, the patients received marrow transplants containing only a limited number of MSCs - approximately 1/250000 nucleated cells at 35 years of age - in contrast to the purified MSC product that is used in the majority of clinical trials[36].

Since then, several studies in animal models and patients have shown that MSCs are capable of migrating and homing to a variety of tissues. Early studies of intra-uterine MSC transplantations in animal models showed that donor-derived non-haematopoietic cells were present in the bone marrow, thymus, spleen and liver[37,38]. Devine et al[30] and Chapel et al[7] performed MSC transplantations in non-human primates and observed MSCs in a variety of tissues, with highest numbers in the gastro-intestinal tract. The percentage of MSCs in the different tissues was estimated between 0.1% and 2.7%[7,30]. Erices et al[39] described the homing and survival of human cord blood-derived MSCs in the bone marrow of immunodeficient (nude) mice after systemic infusion[39]. Several studies in patients have also shown MSC homing[40-43].

A few groups have analysed the dynamics of MSC migration after systemic infusion using different techniques. Immediately after infusion, the MSCs are trapped in the lungs, and, subsequently, the cells are cleared from the lungs and distributed to other tissues[44,45]. The cells could be injected intravenously or intra-arterially for systemic infusion. The former is the least invasive method and the easiest to perform; however, as the MSCs were trapped in the lungs, different administration routes were examined. IA injection, which is already more risky because of the arterial puncture, also appears to entail a risk of development of microvascular occlusions called passive entrapment[27,46]. In addition, there have been reports that MSCs have a procoagulant activity[26,47]. A few years ago, a group from the Karolinska Institute reported that MSCs, particularly those that had been subjected to extended passaging and co-culture with activated lymphocytes, exhibited increased prothrombotic capacities; this effect was dose-dependent[47]. Gleeson et al[26] reported that MSCs express functionally active tissue factor. When MSCs were injected in the coronary arteries of a porcine myocardial infarction model, it resulted in a decreased coronary flow reserve. This effect could be reversed by the co-administration of heparin, an antithrombin agent[26].

Kyriakou et al[48] have studied the factors influencing short-term bone marrow homing of MSCs. The stem cells were observed in the bone marrow, spleen, liver and lungs 24 h after IV injection. It was observed that homing increased in younger animals and after irradiation but decreased with increasing passage numbers of the cells[48]. Several other groups have also shown that MSC homing improves after irradiation[7,8,30,49-52].

The expression of molecules involved in MSC migration, homing and functionality has been widely studied.

Different molecules are involved/necessary for the different steps in the homing process. The selectins on the endothelium are primarily involved in the first step. For bone marrow homing in particular, the expression of haematopoietic cell E-/L-selectin ligand (HCELL), a specialized glycoform of CD44 on the migrating cell, is very important[53]. Although MSCs express CD44, they do not express HCELL[54].

The G-protein coupled receptors that are involved in the activation step are typically chemokine receptors. It has been extensively demonstrated that the CXCR4-stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1) axis is critical for bone marrow homing[55]. Both molecules are very physiologically important, as knock-outs are lethal due to bone marrow failure and abnormal heart and brain development[56,57]. The expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 on MSCs is controversial. Some groups did not observe expression of the receptor, while other studies demonstrated that CXCR4 was expressed, albeit at low levels on the membrane, which affected migration in response to SDF-1[58-70].

Integrins are important players in the stable activation-dependent arrest in the third step of homing. It has been shown that the inhibition of integrin β1 can abrogate MSC homing[71]. Integrins form dimers that bind to adhesion molecules on the endothelial cells. Integrin α4 and β1 combine to form very late antigen 4 (VLA-4), which interacts with vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1). It has been shown that the VCAM-1-VLA4 interaction is functionally involved in MSC homing[72,73].

In the final step of diapedesis or transmigration through the endothelial cell layer and the underlying basement membrane, lytic enzymes, such as the matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), are required to cleave the components of the basement membrane. In particular, the gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 have important roles in this step because they preferentially degrade collagen and gelatin, two of the major components of the basement membrane[74,75]. We have shown that MSC migration is regulated by MMP-2 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 3 (TIMP-3)[76]. Membrane type 1 MMP (MT1-MMP) has also been reported to play a role in MSC migration[63]. MMPs are secreted as pro-enzymes. ProMMP-2 is activated by interactions with MT1-MMP and TIMP-2 and is inhibited by TIMP-1. This explains why the MMP-2, MT1-MMP or TIMP-2 knock-down decreased the invasive capacity of MSCs, and why TIMP-1 knock-down resulted in increased invasion in the study of Ries et al[77].

Table 1 gives an overview all of the migration and homing molecules that are reported to be expressed on human MSCs. Figure 1 shows a schematic overview of the molecules involved in human MSC bone marrow homing.

| Group | Molecule | Source | Transcript | Protein | Functional assay |

| Chemokine receptors | CCR1[70,77-82] | BM[70,77-79,81] | Yes[70,77,79,80] | Yes[70,77-82] | In vitro migration[70,77,78,80], in vivo tail vein injection in mice for tissue distribution[77] |

| WJ[79] | |||||

| AT[80] | |||||

| PB[82] | |||||

| CCR2[68,78,81,82] | BM[68,78,81,82] | Yes[68,82] | Yes[68,78,81,82] | In vitro migration[68,78,82] | |

| CCR3[68,78,81-83] | BM[68,78,81,83] | Yes[68] | Yes[68,78,81,82,83] | In vitro migration[68,78] | |

| PB[82] | |||||

| CCR4[68,77,78,82] | BM[68,77,78,82] | Yes[68,77,82] | Yes[68,77,78] | In vitro migration[68,77,78,82], in vivo tail vein injection in mice for tissue distribution[77] | |

| No[82] | |||||

| CCR5[68,78,81-83] | BM[68,78,81,83] | Yes[68] | Yes[68,78,81,82] | In vitro migration[68,78] | |

| PB[82] | |||||

| CCR6[78,81,83] | BM[78,81,83] | Yes[82] | Yes[78,82] | In vitro migration[78] | |

| CCR7[70,78,80-83] | BM[70,78,81,83] | Yes[70,80,83] | Yes[70,78,80-83] | In vitro migration[70,78,83] | |

| AT[80] | |||||

| PB[82] | |||||

| CCR8[78,82,83] | BM[78,83] | Yes[82] | Yes[78,82,83] | In vitro migration[78] | |

| PB[82] | |||||

| CCR9[70,78,81-83] | BM[70,78,81,83] | Yes[70,83] | Yes[70,78,81-83] | In vitro migration[70,78] | |

| PB[82] | |||||

| CCR10[77,78,81,83] | BM[77,78,81,83] | Yes[77,83] | Yes[77,78,81] | In vitro migration[77,78], in vivo tail vein injection in mice for tissue distribution[77] | |

| CXCR1[78,81,82,84] | CB[84] | Yes[83,84] | Yes[78,81,82,84] | In vitro migration[78,83,84], in vivo injection in brain[84] | |

| BM[78,81,82] | |||||

| PB[82] | |||||

| CXCR2[62,78,81-83] | BM[62,78,81,83] | Yes[62,83] | Yes[62,78,81-83] | In vitro migration[62,78,83], in vivo lung metastasis model[62] | |

| PB[82] | |||||

| CXCR3[78,81-83] | BM[78,81,83] | Yes[83] | Yes[78,81-83] | In vitro migration[78] | |

| PB[82] | |||||

| CXCR4[60,62,65,66,68,70,76,78,80-83,85,90] | BM[60,62,68,70,76,78,81,83,85] | Yes[60,62,66,68,70,76,80,83,85] | Yes[62,65,66,68,70,76,78,80-83,85,90] | In vitro migration[60,62,65,66,68,70,76,78,80,83,85,90], in vivo lung metastasis model[62], tail vein injection in sublethally irradiated mice[66] | |

| CB[65,85,90] | |||||

| Foetal BM[66] | |||||

| AT[80] | |||||

| PB[82] | |||||

| CXCR5[68,70,77-83] | BM[68,70,77,78,81,83] | Yes[68,70,77,79,80,83] | Yes[68,70,77-83] | In vitro migration[68,70,77,78,80], in vivo tail vein injection in mice for tissue distribution[77] | |

| WJ[79] | |||||

| AT[80] | |||||

| PB[82] | |||||

| CXCR6[70,78,80-83] | BM[70,78,81,83] | Yes[70,80,83] | Yes[70,78,80-83] | In vitro migration[70,78,80] | |

| AT[80] | |||||

| PB[82] | |||||

| CXCR7[60,82] | BM[60] | Yes[60] | Yes[82] | In vitro migration[60] | |

| PB[82] | |||||

| CX3CR[82] | BM[82] | Yes[82] | Yes[82] | ||

| PB[82] | |||||

| XCR[82,82] | BM[82] | Yes[82] | Yes[82] | ||

| PB[82] | |||||

| Adhesion molecules | VCAM-1[74,85,86] | BM[74,85,86] | Yes[85] | Yes[85,86] | In vitro migration[74] |

| CB[86] | |||||

| AT[86] | |||||

| ICAM-2[85] | BM[85] | Yes[85] | Yes[85] | ||

| CD62[11,17,54,86-89] | BM[11,54,86-89] | Yes[11,17,54,86-89] | In vivo homing in a mouse model[54] | ||

| CB[17,86,87,89] | |||||

| AT[86-89] | |||||

| Skin[87] | |||||

| LFA-3[85] | BM[85] | Yes[85] | Yes[85] | ||

| Integrin α1[11,85,87] | BM[11,85,87] | Yes[85] | Yes[11,85,87] | ||

| CB[87] | |||||

| AT[87] | |||||

| Skin[87] | |||||

| Integrin α2[85] | BM[85] | Yes[85] | Yes[85] | ||

| Integrin α3[11,85] | BM[11,85] | Yes[85] | Yes[11,85] | ||

| Integrin α5[11,85] | BM[11,85] | Yes[85] | Yes[11,85] | ||

| Integrin α6[85] | BM[85] | Yes[85] | Yes[85] | ||

| MT1-MMP[68,77,85] | BM[68,77,85] | Yes[68,77,85] | Yes[68,77,85] | In vitro migration[68,77,85] | MT1-MMP[68,77,85] |

| CB[85] | |||||

| TIMP-1[68,77,90] | BM[68,77,90] | Yes[68,77,90] | Yes[68,77,90] | In vitro migration[68,77,90] | TIMP-1[68,77,90] |

| TIMP-2[68,90] | BM[68,77,90] | Yes[68,77,90] | Yes[68,77,90] | In vitro migration[68,77,90] | TIMP-2[68,90] |

| TIMP-3[76] | BM[76] | Yes[76] | Yes[76] | In vitro migration[76] | TIMP-3[76] |

| c-met (HGF-R)[68,80,85] | BM[68,85] | Yes[68,80,85] | Yes[68,85] | In vitro migration[85,68] | c-met (HGF-R)[68,80,85] |

| CB[85] | No[80] | ||||

| AT[80] | |||||

| PDGFRα[68,80,87] | BM[68,87] | Yes[68,80] | Yes[68,80,87] | In vitro migration[68,80] | PDGFRα[68,80,87] |

| AT[80,87] | |||||

| CB[87] | |||||

| Skin[87] | |||||

| PDGFRβ[68,80,87] | BM[68,87] | Yes[68,80] | Yes[68,80,87] | In vitro migration[68,80] | PDGFRβ[68,80,87] |

| AT[80,87] | |||||

| CB[87] | |||||

| Skin[87] | |||||

| FGF-R1[80] | AT[80] | Yes[80] | Yes[80] | In vitro migration[80] | FGF-R1[80] |

| FGF-R2[68] | BM[68] | Yes[68] | Yes[68] | In vitro migration[68] | FGF-R2[68] |

| EGF-R[68,78] | BM[68,78] | Yes[68,80] | Yes[68,80] | In vitro migration[68,80] | EGF-R[68,78] |

| AT[80] | |||||

| IGF-R1[68] | BM[68] | Yes[68] | Yes[68] | In vitro migration[68] | IGF-R1[68] |

| TIE-2[68] | BM[68] | Yes[68] | Yes[68] | In vitro migration[68] | TIE-2[68] |

| TGFRB2[80] | AT[80] | Yes[80] | Yes[80] | In vitro migration[80] | TGFRB2[80] |

| TNFRSF1A[80] | AT[80] | Yes[80] | Yes[80] | In vitro migration[80] | TNFRSF1A[80] |

In addition to the expression of classic homing molecules, different groups have also described the expression of growth factor receptors on MSCs. Several studies have shown that growth factors can also induce MSC migration. For example, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) AB and BB can induce MSC migration in vitro[68,80,91]. Another growth factor involved in MSC migration is hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which binds to c-met[63,68,80]. Both PDGF-BB and HGF have been loaded on gels or scaffolds as a means to improve the in vitro migration of MSCs[92,93].

Several groups have demonstrated MSC homing and migration, but only a small proportion of systemically administered MSCs actually reaches and remains in the target tissue[30]. Several factors are assumed to be involved. First, the expression of homing molecules on MSCs is limited. For example, the membrane expression of CXCR4, a critical receptor for homing to bone marrow, is very low, and some groups even claim there is no CXCR4 expression at all[58-70]. Another concern is that the MSCs appear to lose the expression of homing molecules during in vitro expansion[70,94]. Additionally, there is also heterogeneous expression of homing molecules in MSC cultures and in MSCs derived from different tissues (adipose tissue vs bone marrow), which show a different expression profile of homing molecules[95].

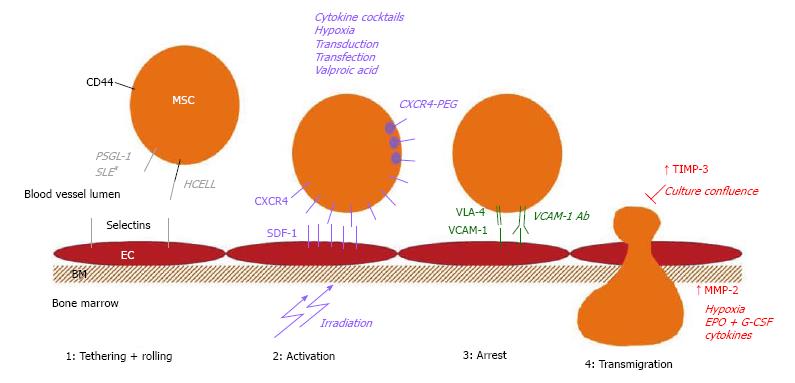

Because improving the homing efficiency to and retention of MSCs in a target tissue after systemic administration would improve their therapeutic effects, many groups are investigating methods to achieve this goal. Different strategies have been developed: the mode of administration could be modified, the MSC culture conditions can be adapted to optimize the expression of homing molecules, the cell surface receptors could be engineered to improve homing or the target tissue could be modified to better attract the MSCs. Again, we will mainly focus on the strategies that might improve the bone marrow homing of MSCs. The homing molecules involved in homing to bone marrow can also be of importance in homing to other organs or sites of injury, such as the CXCR4-SDF-1 interaction for homing to the injured myocardium[96]. However, we believe that methods that can upregulate or induce the expression of the homing molecules that are involved in bone marrow homing of MSCs are valuable. They show a potential means for improving bone marrow homing, even though the data supporting/proving this are not yet available. Figure 2 provides an overview of the methods that could be used to improve the bone marrow homing of MSCs.

In vivo studies have repeatedly shown that MSCs are trapped in the lung after intravenous injection. When mice were treated with a vasodilator prior to MSC infusion, there was a clear decrease in the number of trapped MSCs in the lungs and a significant increase in MSC homing to the marrow of the long bones[44]. Yukawa et al[97] transplanted MSCs in combination with heparin treatment and found that this strategy also significantly decreased MSC trapping in the lungs.

Because MSCs appear to downregulate homing molecule expression during expansion, many groups are investigating different ways to induce or upregulate the expression of important homing molecules.

Much effort has been focused on increasing CXCR4 expression on the membrane. One way to achieve this is by adding cytokines or cytokine cocktails to the culture medium during expansion. Shi et al[66] showed that exposure to a combination of flt3 ligand, stem cell factor (SCF), IL 3, IL 6 and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) increased both the intracellular and membrane expression of CXCR4 on cultured MSCs. More of the pretreated cells migrated towards an SDF-1 gradient, and there was no effect of the pretreatment on the function of the MSCs in supporting haematopoiesis. In vivo homing experiments where MSCs were intravenously injected into sublethally irradiated mice revealed a significant increase in bone marrow homing after the cytokine treatment[66]. Other molecules that have been shown to increase CXCR4 expression are insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα), IL 1β, interferon γ (IFNγ)[68,98-100]. CXCR4 expression could also be upregulated by treating cultured MSCs with glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) inhibitors, resulting in an improved in vitro migration capacity, without affecting cell viability[101]. Exposure to complement 1q (C1q) has been shown to increase MSC migration towards SDF-1, although there was no significant increase in CXCR4 expression. Therefore, it was postulated that C1q exposure increases the MSCs’ ability to sense SDF-1 gradients[65].

Treatments with GSK-3β inhibitors and C1q also increase MMP expression in MSCs, which are important for the degradation of the basement membrane during extravasation[60,101]. A combination of the haematopoietic growth factors erythropoietin (EPO) and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) has also been reported to increase MMP-2 expression in MSCs and improve their motility[102].

There is also evidence that the epigenetic modulation induced by a short-term exposure to valproic acid results in increased expression of CXCR4 and MMP-2 in cultured MSCs and an increase in their migration towards SDF-1. There was no impact of this priming on the differentiation capacity of the cells[103].

Another approach that is under investigation is culturing MSCs under hypoxic conditions. Several groups have shown that these conditions result in increased CXCR4 expression and an improvement in MSC migration both in vitro and in vivo. This effect of hypoxia not only appears after short-term exposure but also in response to continuous culture in hypoxic conditions[104-108]. The increase in CXCR4 expression is reported to be regulated by an increase in hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) 1α[108]. Hypoxia also leads to differential expression of MMPs. For example, a decrease in MMP-2 secretion and an increase in MT1-MMP secretion and activity has been described in MSCs cultured under hypoxic conditions[104]. However, one could be concerned that culturing MSCs under hypoxia might change their behaviour. Valorani et al[109] reported that adipose tissue-derived MSCs cultured under hypoxic conditions exhibited an increased adipogenic or osteogenic differentiation capacity[109]. Crowder et al[110] reported that concurrent exposure to extreme hypoxia (0.5%) and a carcinogenic metal (nickel) induces carcinogenic changes in late passage MSCs. They did not observe these changes in early passage control cells[110].

A simpler modification of culture conditions is to maintain lower confluence. Our group found that MSCs that were cultured to complete confluence had a lower migration capacity than MSCs maintained at a low confluence. The cells cultured at higher confluence secrete more TIMP-3, an inhibitor of MMPs, which decreases migration compared to the MSCs cultured at low confluence[76].

Finally, MSCs are a heterogeneous cell population, and a particular subset of MSCs might have better homing abilities. MSCs were separated based on their expression of Stro1 and cultured further; these cells exhibited different migration capacities in NOD/SCID transplantation experiments. The amount of Stro1- MSCs was higher than the amount of Stro1+ MSCs in the target tissues of the mice, such as the bone marrow and spleen, after systemic administration via the retro-orbital plexus[111].

As already mentioned, MSCs express low levels of CXCR4, if any at all[58,59]. Because the CXCR4-SDF1 axis is important for bone marrow homing[20,112], many groups have designed transfection or transduction experiments in which CXCR4 expression plasmids are either nonvirally or virally introduced into the cells. Viral transduction is the most efficient method for obtaining high and stable expression levels in the target cells. CXCR4 overexpression resulted in improved MSC homing to the bone marrow after intracardiac injection into a NOD/SCID transplant model[112]. In a similar model, the overexpression of integrin α4, a subunit of VLA4 that interacts with VCAM-1, also resulted in increased bone marrow homing[113]. However, there are some draw-backs to this technique. Most importantly, there is the concern that the use of viral vectors to introduce the plasmid DNA poses a risk of insertional oncogenesis. Techniques for site-directed integration have been developed to circumvent this problem[114]. Moreover, there is also a risk of adverse immune reactions and the production costs are high[115].

Different modes of non-viral transfection of plasmid DNA have been developed. One group overexpressed CXCR4 in MSCs using mRNA nucleofection. They obtained 90% expression of the surface receptor, but cell viability was only 62% and no increase in MSC homing could be observed[96]. Another group investigated the feasibility of inserting a short interfering RNA in MSCs using ultrasound and microbubbles to promote survival. A significant knock-down of the target (PTEN) could be obtained, but the cells were damaged after the manipulation[116].

Different modes of chemical, non-viral transfection have been studied, including the use of lipid agents. Although these techniques are easier to scale up and less expensive than viral transduction, they come with a price. The transfection efficiencies are significantly lower because approximately 35% of the MSCs express the transfected protein compared to over 90% of the cells after viral transduction[20].

A method to improve homing efficiency of MSCs that has garnered interest in recent years is cell surface engineering, i.e., a transient modification of the cell surface. Because transmigration through the activated endothelium takes 1-2 h, these transient alterations can be instrumental in improving MSC homing[117]. It has been shown that these modifications do not impact cell viability, proliferation, adhesion or differentiation[118-121]. For cell surface engineering, most groups focus on improving the first step of the homing process, tethering and rolling, by modulating the expression of adhesion molecules[54,118,120,121]. Since the first publications, many groups have developed different techniques for the cell surface modifications of MSCs.

A seminal paper in this field was published in 2008, when Sackstein et al[54] reported that they had converted the native CD44, which is readily expressed on MSCs, into the haematopoietic cell E-selectin/L-selectin ligand (HCELL) glycoform ex vivo[54]. E-selectin plays a key role in haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) homing to the bone marrow; however, MSCs do not express P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) or HCELL, the two E-selectin ligands that are required for HSC bone marrow homing, thus impairing their homing capacity to the bone marrow[54,122]. MSCs natively express CD44. In this study, Sackstein et al[54] were able to alter sialofucosylation ex vivo and transform CD44 into the HCELL glycoform. This treatment had no effect on the viability or phenotype of the cells. In vivo homing experiments that injected MSCs into the tail veins of NOD/SCID mice showed that the HCELL+ MSCs homed to the bone marrow, even in the absence of CXCR4, in contrast to the unmanipulated MSCs[54].

Sialyl Lewis X (SLEX) is the active site of PSGL-1. Therefore, introducing this molecule into the MSC cell membrane should also lead to improved MSC homing. Sarkar et al[118] used biotinylated microvesicles to modify the MSCs. When the vesicles were brought into contact with the MSCs, they integrated into the cell membrane, thus generating biotinylated MSCs. Using a streptavidin linker, biotinylated SLEX could be immobilized on the cell surface. The accessibility of the lipids integrated in the cell membrane was assessed and the researchers found they could still be detected after 4 h, but the intensity had already decreased to 50% compared with that at 0 h. After 8 h, all signals were lost, confirming that the modification is indeed transient. In vitro tests showed that the SLEX-expressing MSCs exhibited improved adhesion under shear stress compared to the sham-treated MSCs[118].

Cheng et al[120] described a rapid (30 min) procedure to conjugate peptide K, an E-selectin binding peptide, to the MSC membrane. The MSC viability and proliferation rates were normal after engineering and their differentiation capacity was also maintained. In an in vitro model of inflamed endothelium, they subsequently demonstrated that the engineered MSCs adhered better than the control MSCs under shear stress[120].

Lo et al[121] described yet another engineering method to improve MSC binding to selectins and facilitate tethering and rolling. The first 19 amino acids of PSGL-1 (Fc19) were combined with an IgG tail and with an SLEX glycan to engineer a pan-selectin-binding ligand. Tests in flow chambers showed that these MSCs were indeed capable of adhesion under shear stresses[121].

However, adhesion molecules are not the sole targets of the cell surface engineers. There is also interest in conjugating antibodies to the cell surface. Protein painting is a technique that binds antibodies to the cell surface. First, the palmitated proteins acting as docking stations for the antibodies are integrated into the cell membrane, and, subsequently, antibodies can be bound to the cell without losing affinity and with no impact on the viability and differentiation potential of the engineered cells[123]. One example using this technique is the binding of intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 antibodies to MSCs, which increased the binding of these cells to endothelial cells[124]. This same protein painting technique has been applied to express VCAM-1 antibodies on MSCs, resulting in improved homing. In this study, the target tissues were the mesenteric lymph nodes and the colon. However, this technique might also be applied to improve homing to other organs, such as the bone marrow, because VCAM-1 is implicated in the bone marrow homing of MSCs[125].

Recently, a method was also described in which recombinant CXCR4 is bound to the cell surface of MSCs using lipid-PEG. In a one-step mixture procedure, recombinant CXCR4 could be transiently expressed on MSCs, leading to migration towards SDF-1 in a concentration-dependent manner[119].

Finally, MSC migration and homing can be influenced by modifying the target tissue. In early homing studies, it was already shown that altering the target tissue by irradiation increases MSC homing[7,8]. After chemo- and radio-therapy, there are increased levels of SDF-1 in the bone marrow, thus increasing its attraction for HSCs and MSCs[126]. There are also reports of manipulating MSC migration with ultrasound or magnetic or electric fields[127-129]. However, these techniques do not appear to be very practical and they need adequate expression of homing molecules. For example, application of electrical fields could induce heat and electrochemical products near the electrodes. On the other hand, ultrasound-guided delivery might be more challenging in deep organs. Finally, homing directed by a magnetic field might require the implantation of a magnet in or near the tissue of interest[127-129].

In animal models and clinical studies, only limited engraftment or no engraftment at all is often observed, raising the question of whether tissue-specific homing is required for the therapeutic effect of MSCs[30,42]. A study on the use of systemically administered MSCs for the treatment of stroke in an animal model also showed very limited migration of MSCs to the tissue of interest, the brain. However, the researchers found that MSC homing to the spleen was important and correlated with a reduced infarct size and peri-infarct inflammation. They propose that MSCs exert a beneficial effect by abrogating secondary, inflammation-related cell death[130]. These data show that tissue-specific MSC homing is important, even though the target tissue is not the brain, as one would expect in a stroke model. Fernández-García et al[131] performed cotransplantation studies with MSCs and HSCs and found that cotransplantation improves short- and long-term haematopoietic reconstitution. This was the result of MSC and HSC interactions, and they propose that MSCs act as carriers that facilitate HSC homing to the bone marrow[131].

Manipulating stem cells, such as MSCs, to improve their homing capacities might not only change their migratory capacities but also have other consequences. For example, Liu et al[132] claim that the CXCR4-SDF-1 axis plays an important role in MSC survival because MSCs pretreated with SDF-1 exhibited significantly improved survival and proliferation. These effects could be partially inhibited by AMD3100, an inhibitor of CXCR4[132]. The pretreatment of MSCs with cytokines also revealed some conflicting observations. In a recently published paper, Kavanagh et al[133] report that licensing murine MSCs with inflammatory cytokines does not improve homing to the injured gut in an ischaemia/reperfusion model in their hands. More importantly, they found that while the untreated MSCs improved tissue perfusion, this effect was abrogated with the pretreated MSCs[133]. However, another group reported positive effects of pretreatment on the biological functions of the MSCs. Szabó et al[134] found that licensing murine MSCs with pro-inflammatory cytokines resulted in a significant reduction in the variability in immunosuppressive capacities of these MSCs. This reduction in variability was due to an increased immunosuppression of clones that were poor inhibitors of T-cell proliferation prior to licensing[134].

The pretreatment of MSCs with different factors or conditions, e.g., hypoxia and inflammatory cytokines, could also modify their response to these treatments. Naaldijk et al[135] found that the oxygen concentration (normoxia vs hypoxia) alters the response of rat and human AT MSCs. They also found that the migration of MSCs isolated from older donors (rat and human) was not significantly impaired compared with the MSCs from young donors[135]. In contrast to this last finding, Choudery described that MSCs from aged mice exhibit diminished effectiveness and increased expression of apoptotic and senescent genes[136].

In this review, we have described different techniques for improving MSC homing and the expression of homing molecules on MSCs. Importantly, however, the expression of homing molecules and the resulting migration, homing and biological functions of MSCs might easily be altered unintentionally. Currently, many different protocols are used to expand MSCs for in vitro, animal and clinical studies. These variables can have a major impact on the expression of the homing molecules and the biological functions of MSCs; we will briefly discuss this below.

MSCs were first isolated from bone marrow. Since then, MSCs have been isolated from a wide variety of tissues, including adipose tissue (AT), umbilical cord blood (CB), Wharton’s jelly (WJ), etc.[59,79,80,82]. Several groups have reported differences in the expression of homing molecules in human MSCs isolated from different sources; these are listed in Table 1. Additionally, the MSCs derived from different sources also exhibit differences in their biological functions. For example, AT MSCs might have better immunosuppressive capacities than bone marrow MSCs[95]. On the other hand, bone marrow MSCs appear to be the only MSCs that are capable of forming a haematopoietic niche that can support human haematopoietic tissue in an in vivo model[87].

When using MSCs for organ-specific treatments, one might choose to induce differentiation in vitro before transplantation. However, in vitro differentiation might not always result in a clinical benefit during MSC therapy. In a study using human CB MSCs in a mouse model for liver disease, the researchers found that hepatic differentiated MSCs performed worse than the undifferentiated MSCs. The differentiated MSCs showed decreased expression of the homing molecules and decreased in vivo migration after IV infusion. Additionally, their immunosuppressive capacity was decreased and the expression of HLA DR was increased, thus increasing their immunogenicity[137]. Ullah et al[138] also found that chondrogenic differentiated human MSCs exhibited a significantly reduced in vitro migration capacity than undifferentiated MSCs. However, CCR9 expression and in vitro migration to its ligand, CCL25, were retained in the differentiated MSCs[138].

Many parameters in MSC cultures vary between different research groups, including seeding density, number of passages, basal medium, and growth supplements [foetal bovine serum (FBS) vs platelet lysate (PL)]. All of these factors might have an important impact on MSC function and migration. For example, Cholewa et al[139] found that PL increased MSC proliferation and increased the number of population doublings before senescence compared to FBS. However, they also showed that seeding MSCs at lower densities selected a highly migratory MSC population[139]. There are also reports of MSCs losing their migratory capacity and/or expression of homing molecules after ex vivo expansion[48,94]. After culture, MSCs are harvested with trypsin to detach them for passaging. Chamberlain et al[140] reported that the cell surface expression of chemokine receptors was decreased when the cells were detached with trypsin.

As described above, there is currently substantial variability in the isolation and expansion protocols for MSCs. Research on MSC homing and migration would clearly benefit from standardized MSC expansion protocols. What appears to be a rather minor aspect of the expansion protocol might have a significant impact on MSC function and/or migration. Thus, standardizing MSC expansion protocols would minimize unintentional modifications of the homing molecules. Of course, different culture conditions should be compared to create an optimal expansion protocol. Once this protocol is defined, it will also be easier to evaluate therapeutic efficacy of MSCs in clinical settings. It may be that different clinical applications require different expansion protocols to obtain the desired therapeutic effect.

We summarized the strategies for improving MSC homing. Many of these methods have not yet been validated in vivo. Before they can be translated to the clinic, the techniques with the most promising results should be first validated using in vivo homing models. In these experiments, the migration of engineered MSCs should be compared with the migration of untreated cells, and the therapeutic efficacy of the treated MSCs can also be assessed in animal disease models.

Although MSCs are widely studied and used in many clinical trials in a variety of clinical domains, little is known about the exact mechanisms by which MSCs exert certain therapeutic effects and their homing to certain tissues. Further studies would benefit from a better understanding of MSC biology. Understanding whether and where MSC migration or homing is necessary can help to define the optimal expansion protocols.

Finally, when transitioning to clinical trials, all conditions should be strictly defined, and, ideally, randomized controlled trials would be designed.

MSCs are interesting effector cells that can be used in a variety of therapeutic applications. Systemic administration is often the preferred route of delivery. However, this approach requires that adequate numbers of MSCs migrate and home to the target tissue(s). MSCs do not express many homing receptors, which impairs their migration capacity and hampers their therapeutic efficacy. Studies are ongoing and are needed to further elucidate the MSC homing mechanisms. A better understanding of MSC homing, as well as the factors influencing this process, will allow researchers to optimize the migration capacities of these stem cells and their therapeutic effects in a target tissue.

P- Reviewer: Chapel A, Lui PPY, Mustapha N, Phinney DG S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhyan RK, Latsinik NV, Panasyuk AF, Keiliss-Borok IV. Stromal cells responsible for transferring the microenvironment of the hemopoietic tissues. Cloning in vitro and retransplantation in vivo. Transplantation. 1974;17:331-340. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Prockop Dj, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315-317. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Wang C, Fei Y, Xu C, Zhao Y, Pan Y. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate neurological deficits and blood-brain barrier dysfunction after intracerebral hemorrhage in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:4715-4724. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bashir J, Sherman A, Lee H, Kaplan L, Hare JM. Mesenchymal stem cell therapies in the treatment of musculoskeletal diseases. PM R. 2014;6:61-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chou SH, Lin SZ, Kuo WW, Pai P, Lin JY, Lai CH, Kuo CH, Lin KH, Tsai FJ, Huang CY. Mesenchymal stem cell insights: prospects in cardiovascular therapy. Cell Transplant. 2014;23:513-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | De Becker A, Van Riet I. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy in Hematology: From Laboratory to Clinic and Back Again. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:1713-1729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chapel A, Bertho JM, Bensidhoum M, Fouillard L, Young RG, Frick J, Demarquay C, Cuvelier F, Mathieu E, Trompier F. Mesenchymal stem cells home to injured tissues when co-infused with hematopoietic cells to treat a radiation-induced multi-organ failure syndrome. J Gene Med. 2003;5:1028-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mouiseddine M, François S, Semont A, Sache A, Allenet B, Mathieu N, Frick J, Thierry D, Chapel A. Human mesenchymal stem cells home specifically to radiation-injured tissues in a non-obese diabetes/severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model. Br J Radiol. 2007;80 Spec No 1:S49-S55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nasef A, Mathieu N, Chapel A, Frick J, François S, Mazurier C, Boutarfa A, Bouchet S, Gorin NC, Thierry D. Immunosuppressive effects of mesenchymal stem cells: involvement of HLA-G. Transplantation. 2007;84:231-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nasef A, Chapel A, Mazurier C, Bouchet S, Lopez M, Mathieu N, Sensebé L, Zhang Y, Gorin NC, Thierry D. Identification of IL-10 and TGF-beta transcripts involved in the inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation during cell contact with human mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Expr. 2007;13:217-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nasef A, Zhang YZ, Mazurier C, Bouchet S, Bensidhoum M, Francois S, Gorin NC, Lopez M, Thierry D, Fouillard L. Selected Stro-1-enriched bone marrow stromal cells display a major suppressive effect on lymphocyte proliferation. Int J Lab Hematol. 2009;31:9-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Le Blanc K, Ringdén O. Immunobiology of human mesenchymal stem cells and future use in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:321-334. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Isakova IA, Lanclos C, Bruhn J, Kuroda MJ, Baker KC, Krishnappa V, Phinney DG. Allo-reactivity of mesenchymal stem cells in rhesus macaques is dose and haplotype dependent and limits durable cell engraftment in vivo. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Eliopoulos N, Stagg J, Lejeune L, Pommey S, Galipeau J. Allogeneic marrow stromal cells are immune rejected by MHC class I- and class II-mismatched recipient mice. Blood. 2005;106:4057-4065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 429] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nauta AJ, Westerhuis G, Kruisselbrink AB, Lurvink EG, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Donor-derived mesenchymal stem cells are immunogenic in an allogeneic host and stimulate donor graft rejection in a nonmyeloablative setting. Blood. 2006;108:2114-2120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 520] [Cited by in RCA: 523] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Poncelet AJ, Vercruysse J, Saliez A, Gianello P. Although pig allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells are not immunogenic in vitro, intracardiac injection elicits an immune response in vivo. Transplantation. 2007;83:783-790. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Oh W, Kim DS, Yang YS, Lee JK. Immunological properties of umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Cell Immunol. 2008;251:116-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | von Bahr L, Sundberg B, Lönnies L, Sander B, Karbach H, Hägglund H, Ljungman P, Gustafsson B, Karlsson H, Le Blanc K. Long-term complications, immunologic effects, and role of passage for outcome in mesenchymal stromal cell therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:557-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fouillard L, Chapel A, Bories D, Bouchet S, Costa JM, Rouard H, Hervé P, Gourmelon P, Thierry D, Lopez M. Infusion of allogeneic-related HLA mismatched mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of incomplete engraftment following autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2007;21:568-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Park JS, Suryaprakash S, Lao YH, Leong KW. Engineering mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative medicine and drug delivery. Methods. 2015;84:3-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Qiao B, Shui W, Cai L, Guo S, Jiang D. Human mesenchymal stem cells as delivery of osteoprotegerin gene: homing and therapeutic effect for osteosarcoma. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:969-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hammer K, Kazcorowski A, Liu L, Behr M, Schemmer P, Herr I, Nettelbeck DM. Engineered adenoviruses combine enhanced oncolysis with improved virus production by mesenchymal stromal carrier cells. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:978-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ďuriniková E, Kučerová L, Matúšková M. Mesenchymal stromal cells retrovirally transduced with prodrug-converting genes are suitable vehicles for cancer gene therapy. Acta Virol. 2014;58:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | François S, Usunier B, Douay L, Benderitter M, Chapel A. Long-Term Quantitative Biodistribution and Side Effects of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (hMSCs) Engraftment in NOD/SCID Mice following Irradiation. Stem Cells Int. 2014;2014:939275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sarkar D, Spencer JA, Phillips JA, Zhao W, Schafer S, Spelke DP, Mortensen LJ, Ruiz JP, Vemula PK, Sridharan R. Engineered cell homing. Blood. 2011;118:e184-e191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gleeson BM, Martin K, Ali MT, Kumar AH, Pillai MG, Kumar SP, O’Sullivan JF, Whelan D, Stocca A, Khider W. Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Have Innate Procoagulant Activity and Cause Microvascular Obstruction Following Intracoronary Delivery: Amelioration by Antithrombin Therapy. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2726-2737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Walczak P, Zhang J, Gilad AA, Kedziorek DA, Ruiz-Cabello J, Young RG, Pittenger MF, van Zijl PC, Huang J, Bulte JW. Dual-modality monitoring of targeted intraarterial delivery of mesenchymal stem cells after transient ischemia. Stroke. 2008;39:1569-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Misra V, Ritchie MM, Stone LL, Low WC, Janardhan V. Stem cell therapy in ischemic stroke: role of IV and intra-arterial therapy. Neurology. 2012;79:S207-S212. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Ikehara S. A novel BMT technique for treatment of various currently intractable diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2011;24:477-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Devine SM, Cobbs C, Jennings M, Bartholomew A, Hoffman R. Mesenchymal stem cells distribute to a wide range of tissues following systemic infusion into nonhuman primates. Blood. 2003;101:2999-3001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 568] [Cited by in RCA: 554] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fouillard L, Francois S, Bouchet S, Bensidhoum M, Elm’selmi A, Chapel A. Innovative cell therapy in the treatment of serious adverse events related to both chemo-radiotherapy protocol and acute myeloid leukemia syndrome: the infusion of mesenchymal stem cells post-treatment reduces hematopoietic toxicity and promotes hematopoietic reconstitution. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2013;14:842-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2222] [Cited by in RCA: 2145] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Agematsu K, Nakahori Y. Recipient origin of bone marrow-derived fibroblastic stromal cells during all periods following bone marrow transplantation in humans. Br J Haematol. 1991;79:359-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Santucci MA, Trabetti E, Martinelli G, Buzzi M, Zaccaria A, Pileri S, Farabegoli P, Sabattini E, Tura S, Pignatti PF. Host origin of bone marrow fibroblasts following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1992;10:255-259. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Koç ON, Peters C, Aubourg P, Raghavan S, Dyhouse S, DeGasperi R, Kolodny EH, Yoseph YB, Gerson SL, Lazarus HM, Caplan AI, Watkins PA, Krivit W. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells remain host-derived despite successful hematopoietic engraftment after allogeneic transplantation in patients with lysosomal and peroxisomal storage diseases. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:1675-1681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Caplan AI. The mesengenic process. Clin Plast Surg. 1994;21:429-435. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Almeida-Porada G, Porada CD, Tran N, Zanjani ED. Cotransplantation of human stromal cell progenitors into preimmune fetal sheep results in early appearance of human donor cells in circulation and boosts cell levels in bone marrow at later time points after transplantation. Blood. 2000;95:3620-3627. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Liechty KW, MacKenzie TC, Shaaban AF, Radu A, Moseley AM, Deans R, Marshak DR, Flake AW. Human mesenchymal stem cells engraft and demonstrate site-specific differentiation after in utero transplantation in sheep. Nat Med. 2000;6:1282-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 929] [Cited by in RCA: 848] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Erices AA, Allers CI, Conget PA, Rojas CV, Minguell JJ. Human cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells home and survive in the marrow of immunodeficient mice after systemic infusion. Cell Transplant. 2003;12:555-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Meleshko A, Prakharenia I, Kletski S, Isaikina Y. Chimerism of allogeneic mesenchymal cells in bone marrow, liver, and spleen after mesenchymal stem cells infusion. Pediatr Transplant. 2013;17:E189-E194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Koç ON, Day J, Nieder M, Gerson SL, Lazarus HM, Krivit W. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell infusion for treatment of metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) and Hurler syndrome (MPS-IH). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;30:215-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 462] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Horwitz EM, Gordon PL, Koo WK, Marx JC, Neel MD, McNall RY, Muul L, Hofmann T. Isolated allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells engraft and stimulate growth in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: Implications for cell therapy of bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8932-8937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1315] [Cited by in RCA: 1202] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ringdén O, Uzunel M, Sundberg B, Lönnies L, Nava S, Gustafsson J, Henningsohn L, Le Blanc K. Tissue repair using allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells for hemorrhagic cystitis, pneumomediastinum and perforated colon. Leukemia. 2007;21:2271-2276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Gao J, Dennis JE, Muzic RF, Lundberg M, Caplan AI. The dynamic in vivo distribution of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells after infusion. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:12-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 700] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Bentzon JF, Stenderup K, Hansen FD, Schroder HD, Abdallah BM, Jensen TG, Kassem M. Tissue distribution and engraftment of human mesenchymal stem cells immortalized by human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:633-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Karp JM, Leng Teo GS. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:206-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1012] [Cited by in RCA: 1086] [Article Influence: 67.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Moll G, Rasmusson-Duprez I, von Bahr L, Connolly-Andersen AM, Elgue G, Funke L, Hamad OA, Lönnies H, Magnusson PU, Sanchez J. Are therapeutic human mesenchymal stromal cells compatible with human blood? Stem Cells. 2012;30:1565-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kyriakou C, Rabin N, Pizzey A, Nathwani A, Yong K. Factors that influence short-term homing of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a xenogeneic animal model. Haematologica. 2008;93:1457-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | François S, Bensidhoum M, Mouiseddine M, Mazurier C, Allenet B, Semont A, Frick J, Saché A, Bouchet S, Thierry D. Local irradiation not only induces homing of human mesenchymal stem cells at exposed sites but promotes their widespread engraftment to multiple organs: a study of their quantitative distribution after irradiation damage. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1020-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Sémont A, François S, Mouiseddine M, François A, Saché A, Frick J, Thierry D, Chapel A. Mesenchymal stem cells increase self-renewal of small intestinal epithelium and accelerate structural recovery after radiation injury. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;585:19-30. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Klopp AH, Spaeth EL, Dembinski JL, Woodward WA, Munshi A, Meyn RE, Cox JD, Andreeff M, Marini FC. Tumor irradiation increases the recruitment of circulating mesenchymal stem cells into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11687-11695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Benderitter M, Gourmelon P, Bey E, Chapel A, Clairand I, Prat M, Lataillade JJ. New emerging concepts in the medical management of local radiation injury. Health Phys. 2010;98:851-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Sackstein R. The bone marrow is akin to skin: HCELL and the biology of hematopoietic stem cell homing. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:215-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Sackstein R, Merzaban JS, Cain DW, Dagia NM, Spencer JA, Lin CP, Wohlgemuth R. Ex vivo glycan engineering of CD44 programs human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell trafficking to bone. Nat Med. 2008;14:181-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 464] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Moll NM, Ransohoff RM. CXCL12 and CXCR4 in bone marrow physiology. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3:315-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, Takakura N, Nishikawa S, Kitamura Y, Yoshida N, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature. 1996;382:635-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1845] [Cited by in RCA: 1781] [Article Influence: 61.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Zou YR, Kottmann AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature. 1998;393:595-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1914] [Cited by in RCA: 1890] [Article Influence: 70.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Wynn RF, Hart CA, Corradi-Perini C, O’Neill L, Evans CA, Wraith JE, Fairbairn LJ, Bellantuono I. A small proportion of mesenchymal stem cells strongly expresses functionally active CXCR4 receptor capable of promoting migration to bone marrow. Blood. 2004;104:2643-2645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 579] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Von Lüttichau I, Notohamiprodjo M, Wechselberger A, Peters C, Henger A, Seliger C, Djafarzadeh R, Huss R, Nelson PJ. Human adult CD34- progenitor cells functionally express the chemokine receptors CCR1, CCR4, CCR7, CXCR5, and CCR10 but not CXCR4. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:329-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Gao H, Priebe W, Glod J, Banerjee D. Activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 and focal adhesion kinase by stromal cell-derived factor 1 is required for migration of human mesenchymal stem cells in response to tumor cell-conditioned medium. Stem Cells. 2009;27:857-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Wang Y, Fu W, Zhang S, He X, Liu Z, Gao D, Xu T. CXCR-7 receptor promotes SDF-1α-induced migration of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in the transient cerebral ischemia/reperfusion rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2014;1575:78-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Lourenco S, Teixeira VH, Kalber T, Jose RJ, Floto RA, Janes SM. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor-CXCR4 is the dominant chemotactic axis in human mesenchymal stem cell recruitment to tumors. J Immunol. 2015;194:3463-3474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Son BR, Marquez-Curtis LA, Kucia M, Wysoczynski M, Turner AR, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ, Janowska-Wieczorek A. Migration of bone marrow and cord blood mesenchymal stem cells in vitro is regulated by stromal-derived factor-1-CXCR4 and hepatocyte growth factor-c-met axes and involves matrix metalloproteinases. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1254-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Ryu CH, Park SA, Kim SM, Lim JY, Jeong CH, Jun JA, Oh JH, Park SH, Oh WI, Jeun SS. Migration of human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells mediated by stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 axis via Akt, ERK, and p38 signal transduction pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Qiu Y, Marquez-Curtis LA, Janowska-Wieczorek A. Mesenchymal stromal cells derived from umbilical cord blood migrate in response to complement C1q. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:285-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Shi M, Li J, Liao L, Chen B, Li B, Chen L, Jia H, Zhao RC. Regulation of CXCR4 expression in human mesenchymal stem cells by cytokine treatment: role in homing efficiency in NOD/SCID mice. Haematologica. 2007;92:897-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Yu Q, Liu L, Lin J, Wang Y, Xuan X, Guo Y, Hu S. SDF-1α/CXCR4 Axis Mediates The Migration of Mesenchymal Stem Cells to The Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Lesion in A Rat Model. Cell J. 2015;16:440-447. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Ponte AL, Marais E, Gallay N, Langonné A, Delorme B, Hérault O, Charbord P, Domenech J. The in vitro migration capacity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: comparison of chemokine and growth factor chemotactic activities. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1737-1745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 694] [Cited by in RCA: 723] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Bhakta S, Hong P, Koc O. The surface adhesion molecule CXCR4 stimulates mesenchymal stem cell migration to stromal cell-derived factor-1 in vitro but does not decrease apoptosis under serum deprivation. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2006;7:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Honczarenko M, Le Y, Swierkowski M, Ghiran I, Glodek AM, Silberstein LE. Human bone marrow stromal cells express a distinct set of biologically functional chemokine receptors. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1030-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Ip JE, Wu Y, Huang J, Zhang L, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. Mesenchymal stem cells use integrin beta1 not CXC chemokine receptor 4 for myocardial migration and engraftment. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2873-2882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Segers VF, Van Riet I, Andries LJ, Lemmens K, Demolder MJ, De Becker AJ, Kockx MM, De Keulenaer GW. Mesenchymal stem cell adhesion to cardiac microvascular endothelium: activators and mechanisms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1370-H1377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Rüster B, Göttig S, Ludwig RJ, Bistrian R, Müller S, Seifried E, Gille J, Henschler R. Mesenchymal stem cells display coordinated rolling and adhesion behavior on endothelial cells. Blood. 2006;108:3938-3944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Steingen C, Brenig F, Baumgartner L, Schmidt J, Schmidt A, Bloch W. Characterization of key mechanisms in transmigration and invasion of mesenchymal stem cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:1072-1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Nagase H, Woessner JF. Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21491-21494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3230] [Cited by in RCA: 3153] [Article Influence: 121.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | De Becker A, Van Hummelen P, Bakkus M, Vande Broek I, De Wever J, De Waele M, Van Riet I. Migration of culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells through bone marrow endothelium is regulated by matrix metalloproteinase-2 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3. Haematologica. 2007;92:440-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Ries C, Egea V, Karow M, Kolb H, Jochum M, Neth P. MMP-2, MT1-MMP, and TIMP-2 are essential for the invasive capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells: differential regulation by inflammatory cytokines. Blood. 2007;109:4055-4063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Smith H, Whittall C, Weksler B, Middleton J. Chemokines stimulate bidirectional migration of human mesenchymal stem cells across bone marrow endothelial cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:476-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Balasubramanian S, Venugopal P, Sundarraj S, Zakaria Z, Majumdar AS, Ta M. Comparison of chemokine and receptor gene expression between Wharton’s jelly and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:26-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Baek SJ, Kang SK, Ra JC. In vitro migration capacity of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells reflects their expression of receptors for chemokines and growth factors. Exp Mol Med. 2011;43:596-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Chamberlain G, Wright K, Rot A, Ashton B, Middleton J. Murine mesenchymal stem cells exhibit a restricted repertoire of functional chemokine receptors: comparison with human. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Hemeda H, Jakob M, Ludwig AK, Giebel B, Lang S, Brandau S. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha differentially affect cytokine expression and migration properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:693-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Ringe J, Strassburg S, Neumann K, Endres M, Notter M, Burmester GR, Kaps C, Sittinger M. Towards in situ tissue repair: human mesenchymal stem cells express chemokine receptors CXCR1, CXCR2 and CCR2, and migrate upon stimulation with CXCL8 but not CCL2. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:135-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Kim SM, Kim DS, Jeong CH, Kim DH, Kim JH, Jeon HB, Kwon SJ, Jeun SS, Yang YS, Oh W. CXC chemokine receptor 1 enhances the ability of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells to migrate toward gliomas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;407:741-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Majumdar MK, Keane-Moore M, Buyaner D, Hardy WB, Moorman MA, McIntosh KR, Mosca JD. Characterization and functionality of cell surface molecules on human mesenchymal stem cells. J Biomed Sci. 2003;10:228-241. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Kern S, Eichler H, Stoeve J, Klüter H, Bieback K. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1294-1301. [PubMed] |

| 87. | Reinisch A, Etchart N, Thomas D, Hofmann NA, Fruehwirth M, Sinha S, Chan CK, Senarath-Yapa K, Seo EY, Wearda T. Epigenetic and in vivo comparison of diverse MSC sources reveals an endochondral signature for human hematopoietic niche formation. Blood. 2015;125:249-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Al-Nbaheen M, Vishnubalaji R, Ali D, Bouslimi A, Al-Jassir F, Megges M, Prigione A, Adjaye J, Kassem M, Aldahmash A. Human stromal (mesenchymal) stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue and skin exhibit differences in molecular phenotype and differentiation potential. Stem Cell Rev. 2013;9:32-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Peng L, Jia Z, Yin X, Zhang X, Liu Y, Chen P, Ma K, Zhou C. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, cartilage, and adipose tissue. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:761-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Tondreau T, Meuleman N, Stamatopoulos B, De Bruyn C, Delforge A, Dejeneffe M, Martiat P, Bron D, Lagneaux L. In vitro study of matrix metalloproteinase/tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase production by mesenchymal stromal cells in response to inflammatory cytokines: the role of their migration in injured tissues. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:559-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Forte G, Minieri M, Cossa P, Antenucci D, Sala M, Gnocchi V, Fiaccavento R, Carotenuto F, De Vito P, Baldini PM. Hepatocyte growth factor effects on mesenchymal stem cells: proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:23-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | van de Kamp J, Jahnen-Dechent W, Rath B, Knuechel R, Neuss S. Hepatocyte growth factor-loaded biomaterials for mesenchymal stem cell recruitment. Stem Cells Int. 2013;2013:892065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Phipps MC, Xu Y, Bellis SL. Delivery of platelet-derived growth factor as a chemotactic factor for mesenchymal stem cells by bone-mimetic electrospun scaffolds. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Rombouts WJ, Ploemacher RE. Primary murine MSC show highly efficient homing to the bone marrow but lose homing ability following culture. Leukemia. 2003;17:160-170. [PubMed] |

| 95. | Strioga M, Viswanathan S, Darinskas A, Slaby O, Michalek J. Same or not the same? Comparison of adipose tissue-derived versus bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem and stromal cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2724-2752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 540] [Cited by in RCA: 602] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Wiehe JM, Kaya Z, Homann JM, Wöhrle J, Vogt K, Nguyen T, Rottbauer W, Torzewski J, Fekete N, Rojewski M. GMP-adapted overexpression of CXCR4 in human mesenchymal stem cells for cardiac repair. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2073-2081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |