INTRODUCTION

Gene targeting via homologous recombination (HR) presents a precise way to manipulate the mammalian genome at specific loci. Such legitimate site-directed gene targeting requires homology between the donor DNA and the endogenous chromosome, and results in the substitution of DNA between the homologous donor and the endogenous chromosomal sequence (Figure 1). Creating or correcting specific mutations in human stem cells provides great utility in stem cell research; for example, gene knock-in and knockout studies can be carried out to identify and study specific genes expressed and involved in stem cell fate decisions, as well as to create lineage-specific reporter cell lines to screen for signaling pathways in vitro and to monitor differentiation and proliferation of stem cells following transplantation in vivo[1-5]. Targeted gene mutations also facilitate the generation of models to investigate human developmental diseases and screen for potential therapies[6]. Therefore, mediating efficient gene targeting in human stem cells impacts the future application of these cells in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and high-throughput drug discovery and toxicology. Current strategies to manipulate the mammalian cell genome are mostly viral-based; several viral gene delivery systems, including adenovirus, retrovirus, and lentivirus provide high transduction efficiencies, integration into the host cell genome, and high levels of gene expression[7-9]. Lentiviral vectors in particular are highly efficient and result in stable, long-term transgene expression without gene silencing and have been extensively employed in studies of human stem cells[9]. However, viral approaches are often complicated by random vector integration into the host genome that results in genomic instability leading to increased risk of oncogenesis, a major concern for downstream clinical applications[10,11]. In contrast, non-viral methods, such as encapsulation of DNA by lipid or cationic polymer vesicles and naked DNA delivery by either physical (electroporation) or chemical methods, deliver DNA episomally and therefore can in principle avoid insertional mutagenesis due to random integration; however, their application for gene targeting is often restricted by inefficient delivery and by the inability to provide sustained gene expression[12,13]. Thus, despite the enormous potential of genetically modified stem cells in basic and translational research, low rates of targeted gene modifications in human stem cells have limited the realization of these applications.

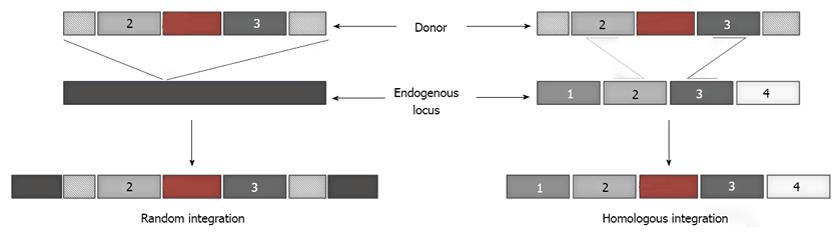

Figure 1 Random and homologous integration.

Introduction of a foreign gene into mammalian cells can either result in its random integration into the endogenous chromosomal DNA, or site-specific integration at the desired location dictated by the homology between the donor DNA and the endogenous target locus.

This review focuses on recent advances in gene targeting techniques, with particular emphasis on technologies that significantly enhance the rates of homology directed genetic engineering of human pluripotent and adult stem cells. These advances open up a range of experimental and therapeutic possibilities, including instruction of stem cell differentiation into therapeutically relevant cells and development of stem cell-based disease models for drug development.

BARRIERS TO GENE TARGETING

Low efficiencies of gene targeting can result from a combination of extracellular and intracellular barriers and increasing our understanding of the contributions of these barriers to gene targeting, as well as strategies to successfully overcome them will benefit the design of efficient vectors for enhanced gene transfer and targeting. The series of barriers that challenge the progress of the gene targeting constructs to the cell nucleus include inefficient transport across the cell membrane and the nuclear envelope, as well as diffusional and metabolic barriers of the cytoplasm that reduce the amount of intact donor DNA constructs that reach the nuclear envelope (Figure 2)[13-16]. Inside the nucleus, exogenous DNA can integrate at predetermined sites via homologous recombination into the genome, although in general the rates of random integration are far greater than those of homologous integration; this low spontaneous frequency of site-specific integration necessitates identification of the small fraction of cells undergoing homologous integration by a combination of positive and negative selection, which require considerable time and expertise[17,18].

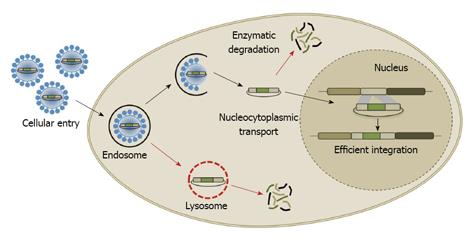

Figure 2 Barriers to gene targeting.

The different barriers that gene delivery vectors must overcome for successful gene targeting include cell binding and internalization, intracellular trafficking and endosomal escape, translocation through the nuclear envelope, and efficient site-specific integration.

Recent years have witnessed the emergence of two main strategies to overcome these barriers: (1) molecular engineering of viral vectors to improve their safety and efficiency and (2) artificial endonucleases that introduce site-specific DNA double-stranded breaks to stimulate targeted integration. Here we will review the use of these novel technologies to carry out homology directed gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and corrections in human stem cells and their potential for advancing basic and applied stem cell research.

MOLECULAR ENGINEERING OF VIRAL VECTORS

Lentivirus-based gene delivery vectors have been widely examined for in vivo and in vitro applications owing to their inherent advantages - specifically, they can efficiently transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells, can be pseudotyped to optimize tropism to a specific cell or tissue of interest, can transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells, and do not induce significant immune responses[19,20]. However, their broad applicability has been limited by the risk of mutagenesis associated with random vector integration into the target genome. Recently, it has been demonstrated that the random insertion event can be prevented by simply introducing mutations in the integrase protein of the virus that facilitates viral genome integration[21]. Such integrase-deficient lentiviral vectors (IDLV) represent new avenues for targeted genetic engineering of human stem cells due to their ability to deliver episomal donor DNA for homologous recombination, while retaining their unique ability to efficiently infect both dividing and non-dividing cells. For example, IDLV have been shown to efficiently transduce both dividing (human embryonic kidney 293) and non-dividing cells (primary neurons and astrocytes) in vitro. And the transgene expression, monitored using GFP fluorescence, was transient in dividing cells and stable in non-dividing cells, consistent with transcription from episomal genetic sequences. Moreover, residual integration activity studies confirmed significantly reduced occurrence (102-103 fold lower) of integration events compared to wild-type lentiviral vectors. IDLVs have also been used to provide clinical benefits for patients with X-Linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD)[22]. ALD is caused by a mutation in the ABCD1 gene encoding for the ALD protein, which leads to accumulation of abnormally high levels of very long chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) causing the adrenal cortex and the myelin membranes that surround nerves to cease functioning. A lentiviral vector encoding the wild-type ABCD1 was introduced into CD34+ cells obtained from ALD patients and the transformed cells were then re-infused into patients. Quantitative analysis using RT-PCR showed that the expression of ABCD1 transgene was four- to five-fold higher than the endogenous mutated ABCD1 gene. Furthermore, after 20-24 mo, the VLCFA levels in patients decreased by up to 39%. Finally, IDLVs encoding for cytokines have been used to induce human monocytes to differentiate into dendritic cells and the resulting induced dendritic cells were functional and capable of stimulating multivalent immune responses in vitro and in vivo[23]. In addition to developing non-integrative vectors, researchers are also pursuing approaches to engineer safer viral vectors by overriding the intrinsic preferences of viral genomic integration for transcriptional start sites (TSS); for example, Lim et al[24] discovered that the addition of DNA binding domains at key sites within retroviral vectors shifted their integration patterns toward regions where TSS are relatively rare. Another approach is the incorporation of Cre recombinase into lentiviral vectors for directed gene targeting[25]. Although this approach is limited by Cre’s specificity for loxP sites that are not native to the mammalian genome, researchers have reported the presence of pseudo loxP sites in the human genome that can be targeted by either wild-type Cre or Cre variants[26].

Recently, adeno-associated virus (AAV) based gene targeting vectors have attracted significant attention as an alternative to the more commonly used lentivirus- and adenovirus-based vectors, mainly because of their ability to deliver transgenes in episomal form and mediate long-term gene expression in dividing and non-dividing cells of numerous human tissues[27]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that AAV vectors can also be used to introduce site-specific genetic modifications in human cells with high efficiencies (up to 1%) that are 103-104-fold higher than plasmid constructs delivered using electroporation[28]. There is evidence supporting that AAV genome’s inverted terminal repeats facilitate its stable integration into the host cell genome using the RAD51/RAD54 pathway of HR in eukaryotes[29]. The ability of AAV to introduce targeted genetic modifications in human cells has been exploited in a variety of applications including the creation of isogenic (knock-in) cells that could be used to study cancer genes in a high-throughput manner. Di Nicolantonio et al[30] recently used this approach to evaluate the effect of drugs on isogenic breast epithelial cells expressing wild-type and mutant alleles of BRAF, KRAS, PIK3CA, and EGFR genes previously implicated in oncogenic pathways. Erlotinib and gefitinib (EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors) were shown to prevent cell proliferation and induce apoptosis selectively in cells carrying the EGFR delE746-A750 deletion, while the cells with KRAS or BRAF mutations were more resistant to these drugs.

AAV-based vectors have also been evaluated for their ability to perform HR mediated gene targeting in human stem cells, and these studies revealed that the gene-targeting frequency for AAV-based vectors was about 1 × 10-5; the low frequencies observed in this study could be attributed to low efficiency of naturally occurring AAV variants in mediating gene delivery to human stem cells[31,32]. Directed evolution approaches, therefore, have been applied to rapidly engineer AAV mutants with the capacity for high efficiency gene delivery to human adult and pluripotent stem cells. Unlike the more deliberate rational design approaches where the virus is modified based on an understanding of the mechanistic consequences of a particular set of changes, directed evolution is a rapid, high-throughput selection approach to create and isolate novel virus mutants with specific properties of interest through appropriate selection pressures from millions of genetic variants. Central to the approach is the highly evolvable AAV capsid that determines the viral infectivity and tropism. This approach employs iterative rounds of genetic diversification, either via error-prone PCR or DNA shuffling and artificial selection pressures to incrementally alter the desired phenotypes. For example, it has been demonstrated that directed evolution of AAV capsids can be used to select variants with the ability to evade antibody neutralization and deliver genes more efficiently that wild-type AAV[33] (Figure 3). Other successful examples include the isolation of AAV variants with altered receptor binding and cell tropism in vitro and in vivo, and enhanced gene delivery[34,35]. Using this approach, researchers have recently created a novel AAV variant - AAV r3.45 that mediates efficient gene delivery to both murine (infection efficiency > 40%) and human (infection efficiency > 30%) neural stem cells (NSCs) when compared to naturally occurring AAV variants (infection efficiency < 1%)[36]. More importantly, this increase in gene delivery efficiency was accompanied by up to 10-fold enhancement in the ability to repair single-base pair mutations in rat NSCs, relative to naturally occurring AAV. In a related study, researchers have also demonstrated the ability of directed evolution approaches to isolate a new AAV variant, AAV 1.9 that exhibited enhanced gene delivery to both human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (infection efficiencies: 40%-50%) that was accompanied by a corresponding increase in AAV 1.9’s capacity for gene targeting, with efficiencies as high as 0.12%, in human ESCs and iPSCs[37].

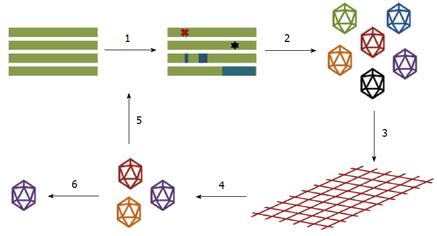

Figure 3 Schematic of steps in the directed evolution of adeno-associated virus.

The wild-type adeno-associated virus (AAV) cap genes are mutated to create large genetic libraries (1) and the mutant cap genes are packaged to generate libraries of AAV particles (2), with each AAV composed of a variant capsid surrounding a viral genome encoding that capsid. The resulting AAV libraries can be subjected to appropriate selective pressures (3) to isolate vectors with modified capsids that facilitate the AAV variants to efficiently surmount these pressures (4). Examples include isolation of AAV variants with the ability to evade neutralizing antibodies, altered receptor binding and cell tropism, and enhanced gene delivery. Successful AAV variants are amplified and recovered (6), or can be subjected to additional rounds of mutagenesis and selection (5). Adapted from Maheshri et al[33] and Bartel et al[35].

Another strategy that has been used to improve the ability of AAV vectors to deliver genes to human cells is to facilitate AAV’s intracellular trafficking (from the cytoplasm to the nucleus) following cellular uptake. Previous studies have shown that inhibition of the EGFR-PTK mediated phosphorylation of AAV capsid proteins at tyrosine residues results in decreased ubiquitination of AAV capsids and their proteasome-mediated degradation, thereby enabling nuclear transport of AAV vectors and improved gene delivery to the cell nucleus[38]. Based on these results, Zhong et al[39] hypothesized that substitution of surface-exposed tyrosine residues on AAV capsids may lead to the design of AAV vectors that facilitate efficient delivery of genes to the nucleus of target cells at lower doses. Consistent with this hypothesis, they observed that site-directed mutagenesis of surface-exposed tyrosine residues significantly improve the transduction efficiency of AAV vectors (about 10-fold increase) in human epithelial cells in vitro. It has also been demonstrated that tyrosine mutant AAV vectors display enhanced gene delivery efficiencies in vivo when compared to wild-type AAV vectors[40]. Although further investigation is warranted, such enhanced AAV vectors engineered through rational design to avoid cytoplasmic degradation could also potentially enhance the efficiencies of AAV-mediated gene targeting in human stem cells.

INTRODUCTION OF SITE-SPECIFIC DNA DOUBLE-STRANDED BREAKS

It has been previously demonstrated that the rate of homologous recombination with donor DNA can be enhanced by the introduction of double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in the mammalian genome using nucleases such as I-SceI[41]. Building upon this important prior work, scientists have recently developed highly specific nucleases such as zinc finger nucleases that can be in principle engineered to target and introduce DNA DSBs at any site in the genome and thus facilitate targeted modifications of endogenous genes. Zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) are synthetic proteins composed of a DNA-binding domain that can be engineered to target desired DNA sequences fused to a non-specific endonuclease domain usually derived from the FokI enzyme[42]. The zinc finger binding domain contains several amino acids stabilized by a zinc ion; such zinc finger domains used in tandem can guide the nonspecific DNA cleaving domain to create a double-strand break at a specific target site within a genome. The cleavage domain must dimerize in order to become active and cleave DNA, thus two ZFN subunits are assembled as heterodimers at the target cleavage site (Figure 4A). Such double-strand breaks are typically repaired by two cellular repair pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (Figure 4B and C).

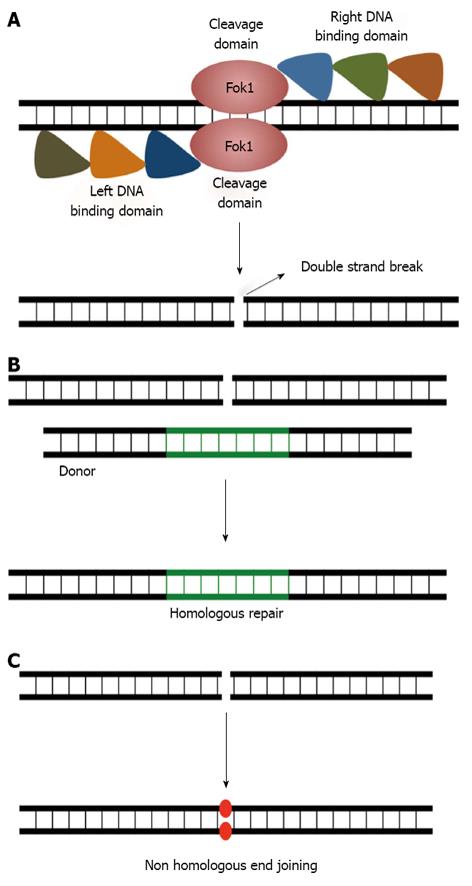

Figure 4 Gene editing using Zinc finger nucleases.

A: Schematic showing a zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) dimer bound to its target locus to introduce a site-specific double-stranded break (DSB) in the chromosome, each ZFN monomer consists of three to six zinc finger domains fused to the DNA-cleavage domain of the FokI endonuclease. B: The DNA DSB can be repaired via either the homologous recombination (HR), or C: the non-homologous end-joining pathway. HR requires a homologous DNA template to accurately repair DSBs in the chromosome, and ensures high fidelity DNA repair. In contrast, non-homologous end joining does not rely on sequence homology between the DNA ends for ligation and can be error-prone.

NHEJ is the major DNA DSB repair pathway in eukaryotic cells and it repairs DNA breaks by direct ligation without the need for a homologous template. Typically, this repair pathway does not create mutations if the two ends are compatible; however, when the two ends are not compatible then NHEJ is prone to cause mutations (insertion or deletion), thereby knocking out the gene (Figure 4C). The ability of ZFNs to facilitate targeted gene knockouts has been recently exploited to disrupt the CCR5 gene in human CD4+ T-cells[43]. CCR5 is a co-receptor used by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) to infect cells of the immune system; the disrupted gene produces malformed CCR5 proteins and confers resistance to HIV infection. The safety and efficacy of T-cells modified by ZFNs targeting the CCR5 gene are currently being evaluated in a clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00842634). Continuing to build upon this work, researchers have also used ZFNs to disrupt the CCR5 gene in human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells[44], and this approach may lead to providing individuals with a self-renewable and potentially lifelong source of HIV-resistant immune cells.

In contrast, DNA repair using the HR pathway relies on a homologous DNA sequence that promotes accurate repair of DSBs (Figure 4B). In addition to gene knockout, this approach also allows precise correction of mutated or dysfunctional human genes to restore normal function[45,46] and targeted gene addition into a specified location in the human cellular genome[47]. Correction of endogenous genes in human cells was first demonstrated in a study using ZFNs that recognize an X-linked severe combined immune deficiency mutation in the IL2Rγ gene, with targeting frequencies as high as 5.3% in human CD4+ T-cells[45]. Recently, it has also been demonstrated that ZFNs can enable targeted gene correction in human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells; in this study, the authors demonstrate gene targeting efficiencies of up to 0.24% when the cells were cotransfected with donor DNA and ZFNs specific to the target site, a > 2400-fold increase in the gene correction efficiencies when compared to without ZFNs (< 10-6). This ability of ZFNs to facilitate site-specific gene corrections has immense potential to facilitate the generation of genetically corrected, patient-derived cells for autologous transplantation therapies. Recently, Joung and coworkers demonstrated in situ correction of the disease causing mutation in iPSCs derived from sickle cell anemia patients[48]. Finally, homology directed gene addition has also been demonstrated in human pluripotent stem cells; ZFNs can be used to target both expressed (OCT4) and non-expressed (PITX3) genes in human pluripotent stem cells and knock-in reporter genes (eGFP) to create reporter cell lines[47]. ZFNs can also be used to knock-in mutations in the mammalian genome to generate in vitro models of human disease. For example, Soldner et al[49] reported the use of ZFNs to develop genetically defined human in vitro models of Parkinson’s disease (PD) by introducing PD-causing α-synuclein mutations into hESCs.

Despite the huge therapeutic potential for ZFNs there are complications with toxicity and specificity. Extensive testing of several variants of ZFNs is required to find the right ZFN pair to minimize off-target binding, therefore making the process both time-consuming and expensive. Recent discoveries of proteins in bacterial pathogens in plants have revealed new DNA binding domains: TAL effectors, which have tandem repeats of amino acids that bind to a single base pair of DNA. These TAL effectors in conjunction with the Fok1 nuclease (TALENs) have been shown to function similar to ZFNs[50,51]. The TALEN technology provides scientists with an increase in modularity allowing for the creation of many variants at little time and cost. Although in its infancy, this new technology has shown great promise; TALEN-mediated double-strand breaks have initiated HR at similar frequencies and precision as ZFNs in human stem cells. For example, Hockemeyer et al[52] demonstrated the use of TALENs to target three endogenous loci (PPP1R12C, OCT4, and PITX3) in hESCs and iPSCs at efficiencies comparable to those reported for ZFNs for the same loci. TALENs have also been recently used to generate human stem cell-based disease models. Cowan and co-workers reported the generation and use of TALEN pairs to efficiently generate mutant alleles of 15 genes in human somatic and pluripotent stem cells and observed minimal off-target events. Further, they demonstrated the utility of TALEN-mediated gene editing to develop detailed genotype-phenotype relationships for four genes known to be directly linked to various human disease conditions[53]. Despite these advances, further research is required to fully evaluate the potential of TALENs before they replace ZFNs for facilitating targeted gene modifications in human stem cells.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

This review highlights the development of two complementary approaches to efficiently modify the human stem cell genome. The first approach involves molecular engineering of viruses, either via rational design or directed evolution, to yield novel vectors that can mediate safe and efficient gene targeting in human stem cells. The second approach is the design of custom endonucleases to target unique predetermined sites in the human genome and facilitate efficient homologous recombination with donor DNA. Each approach individually has yielded remarkable enhancements in gene targeting efficiencies and it is possible that a combination of these complementary approaches can further enhance gene targeting. For example, it has recently been demonstrated that an evolved AAV variant can function effectively in conjunction with ZFNs to mediate highly efficient gene targeting (> 1%) in human pluripotent stem cells. In this study, it was observed that novel AAV vectors can be created to mediate efficient gene targeting in human pluripotent stem cells and in the presence of targeted DSBs generated by the evolved AAV mediated co-delivery of ZFNs, these efficiencies can be further enhanced[37]. The observed enhancements in gene targeting efficiencies of engineered viral vectors in the presence of local DSBs are not limited to AAV; researchers have also demonstrated that baculoviral and IDLV vectors can be used to co-deliver both ZFNs and DNA donor templates to induce efficient gene targeting in human stem cells[54-56]. In these cases, researchers observed high rates of homology directed gene targeting accompanied by low frequencies of random chromosomal integration.

Other strategies may explore the possibility of combining rational vector design with directed evolution - for example, can gene delivery efficiencies of engineered AAV vectors evolved to infect human stem cells be further improved by site-directed mutagenesis of surface-exposed tyrosine residues?

In summary, the considerable progress in enhancing the capacity for homology directed gene targeting bear profound implications on basic and applied human stem cell research. Combining complementary approaches and as-of-yet unexplored possibilities offered by such strategies will yield the next set of developments in this exciting and challenging field.

P- Reviewers Holan V, Thompson EW, Thomas X S- Editor Qi Y L- Editor A E- Editor Wang CH