Published online Nov 26, 2011. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v3.i11.96

Revised: October 23, 2011

Accepted: October 29, 2011

Published online: November 26, 2011

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity throughout the world. To a significant extent, current conventional cancer therapies are symptomatic and passive in nature. The major obstacle to the development of effective cancer therapy is believed to be the absence of sufficient specificity. Since the discovery of the tumor-oriented homing capacity of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), the application of specific anticancer gene-engineered MSCs has held great potential for cancer therapies. The dual-targeted strategy is based on MSCs’ capacity of tumor-directed migration and incorporation and in situ expression of tumor-specific anticancer genes. With the aim of translating bench work into meaningful clinical applications, we describe the tumor tropism of MSCs and their use as therapeutic vehicles, the dual-targeted anticancer potential of engineered MSCs and a putative personalized strategy with anticancer gene-engineered MSCs.

- Citation: Sun XY, Nong J, Qin K, Warnock GL, Dai LJ. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated cancer therapy: A dual-targeted strategy of personalized medicine. World J Stem Cells 2011; 3(11): 96-103

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v3/i11/96.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v3.i11.96

Cancer is one of the top life-threatening diseases, accounting for an estimated one in four human deaths in all age groups in the Untied States in 2010[1]. Current conventional cancer therapies (surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy) are, to a significant extent, symptomatic and passive in nature. Despite improved treatment models, many tumors remain unresponsive to traditional therapy. When fatalities occur, the majority of cancer patients die from the recurrence of metastasis or therapy-related life-threatening complications. The major obstacle limiting the effectiveness of conventional therapies for cancer is their tumor specificity. Therefore, it is critical to explore efficient remedial strategies specifically targeting neoplasms.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are the first type of stem cells to be utilized in clinical regenerative medicine. In addition to their capability of multipotent differentiation, MSCs show many other therapeutically advantageous features, such as easy acquisition, fast ex vivo expansion, the feasibility of autologous transplantation and a powerful paracrine function. More recently, the specific tumor-oriented migration and incorporation of MSCs have been demonstrated in various pre-clinical models, revealing the potential for MSCs to be used as ideal vectors for delivering anticancer agents. With the discovery of specific anticancer genes and the revelation of MSCs’ capacity of tumor-directed migration and incorporation, a new research field has been inspired with the aim of achieving efficient therapy for cancer using engineered MSCs. In the present review, following a general description of MSCs we describe the interactions of MSC with cancers and the dual-targeted anticancer potential of engineered MSCs. We also proposed a putative personalized strategy with anticancer gene-engineered MSCs to treat patients with cancers.

MSCs are a group of adult stem cells naturally found in the body. They were first identified in the stromal compartment of bone marrow by Friedenstein and colleagues in 1960s[2,3]. The exact nature and localization of MSCs in vivo remain poorly understood. In addition to bone marrow, MSCs have been shown to be present in a number of other adult and fetal tissues, including amniotic fluid, heart, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, synovial tissue, pancreas, placenta, cord blood and circulating blood. It has been assumed that basically all organs containing connective tissue also contain MSCs[4]. Among adult stem cells, MSCs are the most studied and the best characterized stem cells. MSCs are primitive cells originating from the mesodermal germ layer and were classically described as giving rise to connective tissues, skeletal muscle cells, and cells of the vascular system. MSCs can differentiate into cells of the mesodermal lineage, such as bone, fat and cartilage cells, but they also have endodermic and neuroectodermic differentiation potential. Indeed, bone marrow-derived MSCs are a heterogeneous rather than homogeneous population[5]. As a result of their supposed capacity of self-renewal and differentiation, bone marrow-derived stromal cells were first considered as stem cells by Caplan and named MSCs[6], although there is some controversy regarding their nomenclature[7]. MSCs have generated considerable biomedical interest since their multilineage potential was first identified in 1999[8].

Owing to their easy acquisition, fast ex vivo expansion, and the feasibility of autologous transplantation, MSCs became the first type of stem cells to be utilized in the clinical regenerative medicine. MSCs can differentiate to several cell types and produce important growth factors and cytokines. They may provide important cues for cell survival in damaged tissues, with or without direct participation in long-term tissue repair[9]. MSCs also have the ability to modify the response of immune cells and are thereby associated with immune-related disorders, especially autoimmune diseases[10,11]. More detailed information on their characterization, tissue distribution and therapeutic potential is described in recent reviews[7,12].

Recently, the specific tumor-oriented migration and incorporation of MSCs have been demonstrated in various pre-clinical models, demonstrating the potential for MSCs to be used as ideal carriers for anticancer agents[13]. In addition to bone marrow-derived MSCs cells obtained from other tissues, such as adipose tissue, can also be potentially used as anticancer gene vehicles for cancer therapy[14,15]. As discussed in the following section, MSCs possess both pro- and anti-cancer properties[16]. It is not an overstatement to describe MSCs as a “double-edged sword” in their interaction with tumors. However, if MSCs are suitably engineered with anticancer genes they could be employed as a valuable “single-edged sword” against cancers.

The first evidence of the tropism of MSCs to tumors was demonstrated by implantation of rat MSCs into rats bearing syngeneic gliomas[17]. Since then, an increasing number of studies have verified MSC tropism toward primary and metastatic tumor locations. Tumors can be characterized as “wounds that never heal”, serving as a continuous source of cytokines, chemokines and other inflammatory mediators[18]. These signals are capable of recruiting respondent cell types including MSCs. Tumor-directed migration and incorporation of MSCs were evidenced in a number of pre-clinical studies in vitro using transwell migration assays and in vivo using animal tumor models. The homing capacity of MSCs has been demonstrated with almost all tested human cancer cell lines, such as lung cancer[19], malignant glioma[20-22], Kaposi’s sarcoma[23], breast cancer[24,25], colon carcinoma[26], pancreatic cancer[27,28], melanoma[29] and ovarian cancer[24]. High frequency of MSC migration and incorporation was observed in in vitro co-culture and in vivo xenograft tumors respectively. These findings were consistent, independent of tumor type, immuno-competence, and the route of MSC delivery. The tropism of MSCs for tumor microenvironment is obvious, but the molecular mechanisms underlying the tumor-directed migration of MSCs have not been fully elucidated. The preconditions for this phenomenon are the production of chemo-attractant molecules from tumor tissue and the expression of corresponding receptors in MSCs[12]. The complex multistep process by which leukocytes migrate to peripheral sites of inflammation has been proposed as a paradigm. The possible pathways and prospective models have been summarized in recent reviews[7,13,30].

Although it is undisputable that MSCs migrate and integrate toward tumor tissues, their fate and function inside the tumor seems ambiguous and sometimes paradoxical, attributable to the complexities of both MSCs and tumor microenvironments. In order to make pertinent use of MSCs, it is essential to understand their advantages and disadvantages with regard to tumorigenesis. Native MSCs have been shown to suppress tumor growth in models of glioma[17], Kaposi’s sarcoma[23], malignant melanoma[31], Lewis lung carcinoma[31], and colon carcinoma[32]. The release of soluble factors by MSCs has also been shown to reduce tumor growth and progression of glioma[17], melanoma and lung carcinoma models[31], and conditioned media from MSCs have been sown to cause the downregulation of NFκB in hepatoma and breast cancer cells resulting in a decrease in their in vitro proliferation[33]. While the precise mechanism underlying the intrinsic antitumor properties of MSCs has not been fully investigated, it is presumably related to the down-regulation of Akt, NFκB and Wnt signaling pathways[13]. On the other hand, several studies have demonstrated that MSCs can augment tumor growth[34-36]. Promotion of tumor growth is possibly mediated by MSC production of immunosuppressive factors and by the contribution of MSCs to tumor stroma and tumor vascularization. The intrinsic anti- and pro-tumorigenic effects of MSCs were summarized in our recent review[12].

Since the discovery of their tumor-directed homing capacity, MSCs have been considered as ideal therapeutic vehicles to deliver anticancer agents. In addition to their tumor-homing properties, MSCs are also easily transduced by integrating vectors due to their high levels of amphotropic receptors[37] and offer long-term gene expression without alteration of phenotype[38,39]. To date, a number of anticancer genes have been successfully engineered into MSCs, which then demonstrate anticancer effects in various carcinoma models. Table 1 summarizes experimental models using MSCs as therapeutic vehicles to deliver anticancer agents.

| Anticancer agent | Anticancer mechanism | Tumor model | Route of MSC admi-nistration | Species: MSC/tumor/host | Ref. |

| CX3CL1 | Immunostimulatory | Lung | iv | Mouse/mouse/mouse | [40] |

| CD | Prodrug converting | Prostate | sc/iv | Human/human/mouse | [41] |

| Colon | sc/iv | Human/human/mouse | [14] | ||

| HSV-tk | Glioma | it | Rat/rat/rat | [42] | |

| Pancreas | iv | Mouse/mouse/mouse | [28] | ||

| IFNα | Immunostimulatory and apoptosis indcing | Melanoma | iv | Mouse/mouse/mouse | [43] |

| Glioma | it/ic | Mouse/mouse/mouse | [44] | ||

| IFNβ | Breast | sc/iv | Human/human/mouse | [29,45] | |

| Pancreas | ip | Human/human/mouse | [27] | ||

| IL2 | Glioma | it/ic | Rat/rat/rat | [17] | |

| IL7 | Immunostimulatory | Glioma | it | Rat/rat/rat | [46] |

| IL12 | Activates cytotoxic lymphocyte and NK cells | Melanoma | iv | Mouse/mouse/mouse | [47] |

| Hepatoma | iv | Mouse/mouse/mouse | [47] | ||

| Breast | iv | Mouse/mouse/mouse | [47] | ||

| IL18 | Immunostimulatory | Glioma | it | Rat/rat/rat | [48] |

| NK4 | Inhibits angiogenesis | Colon | iv | Mouse/mouse/mouse | [49] |

| TRAIL | Induces apoptosis | Glioma | it | Human/human/mouse | [20] |

| Glioma | ic | Human/human/mouse | [50] | ||

| Glioma | iv | Human/human/mouse | [22,51] | ||

| Lung | iv | Human/human/mouse | [52] | ||

| Breast, lung | sc/iv | Human/human/mouse | [53] | ||

| Colon | sc | Human/human/mouse | [54,55] | ||

| Pancreas | iv | Human/human/mouse | [56] |

MSCs can also be utilized to deliver prodrug-converting enzymes. A pioneer example is the combination of herpes simplex virus-thymidine kinase (HSV-tk) (Table 1) gene-engineered MSCs and systemic administration of ganciclovir[57]. Within tumors, HSV-tk is released by engineered MSCs and converts (phosphorylates) the prodrug ganciclovir into its toxic form, thereby inhibiting DNA synthesis and leading to cell death. In addition, there is a substantial bystander effect that leads to the death of neighboring cells. This therapeutic regimen has been successfully employed in glioma[58] and pancreatic cancer[28] experimental models. MSCs have been used to deliver another prodrug-converting enzyme, cytosine deaminase. Following systemic administration, the prodrug 5-fluorocytosine is converted into the highly toxic active drug 5-fluorouracil in tumors. This system has shown therapeutic effectiveness in animal cancer models, such as melanoma[59], colon carcinoma[14], and prostate cancer[41].

The methods of MSC administration has been classified as directional, semi-directional and systemic[60]. For MSC-based cancer therapy, MSCs have been delivered to a variety of tumor models using a number of methods. Systemic delivery methods include intravenous (iv)[29] and intra-arterial[61] injection, whereas, intratumoral implantation[17], intraperitoneal[62] and intracerebral[61] injections, and intratracheal administration[63] are respectively considered as directional and semi-directional deliveries. The selection of delivery route for MSCs is based on consideration of factors, such as the type, location and stage of cancer, and the feasibility of surgical interventions.

As described above, the major limitation on the effectiveness of conventional therapies for cancer treatment is their lack of tumor specificity. Advanced drug targeting of tumor cells is often impossible when treating highly invasive and infiltrative tumors, because of the high level of migration and invasiveness of tumor cells. Uncontrolled drug distribution in the body, resulting in insufficient concentration at the tumor site and toxic concentration on normal cells, is the cause of anticancer inefficacy, and is often the direct cause of side effects and sometimes life-threatening complications. Targeting solid tumors with antitumor gene therapy has also been hindered by systemic toxicity, low efficiency of delivery and nominal temporal expression. However, MSC-mediated anticancer therapies can overcome these limitations, mainly through preferentially homing to sites of primary and metastatic tumors and delivering antitumor agents. Anticancer gene-engineered MSCs are capable of specifically targeting and acting on tumors through multiple selections. The first selection is attributable to the tumor-directed migration and incorporation of MSCs. This phenomenon is independent of tumor type, immunocompetence, and the route of MSC delivery. In addition to the intrinsic anticancer effects of MSCs, the presence of MSCs in the tumor microenvironment allows the agents which are delivered by MSCs to exert their anticancer function locally and constantly. Therefore, the systemic and organ-specific side effects of anticancer agents can be greatly minimized by using this cell-based vector system.

The second level of selection lies in the cancer-specific agents being carried or expressed by MSCs. The research using MSCs as a vehicle for delivering agents to treat cancer has been greatly stimulated by the advances in study on specific anticancer genes. As indicated in Table 1, a number of anticancer genes have been engineered into MSCs, resulting in anticancer effects on various carcinoma models. In the tumor microenvironment, engineered MSCs could serve as a constant source of anticancer agent production, and locally release anticancer agents, which act on adjacent tumor cells thereby efficiently inducing tumor growth inhibition or apoptosis.

Additional selection can be achieved by modifying the vector construction according to organ-specific protein expression. For example, pancreas- or insulinoma-specific anticancer gene-bearing vectors can be made by employing an insulin promoter. Similarly, the unique expression of albumin by hepatocytes, neurotransmitter expression by neurons and surfactant expression by pulmonary alveoli can also be used to construct organ-specific expression vectors. If engineered with organ-specific vectors, MSCs express anticancer proteins only when they home to tumors located in the corresponding organs or to metastatic sites with the same type of cells.

It is worth noting that different types of viral vectors have been used to deliver the targeted genes in cancer gene therapy, including retrovirus, lentivirus, adenovirus and poxvirus. Retrovirus-induced oncogenesis remains the major concern in relation to retrovirus use in clinical applications. The targeted sites of integration, the most crucial factor associated with oncogenicity, are distinct for different retroviruses. In addition to insertional effects on protein-coding genes, insertional activation of non-coding sequences, such as microRNAs, should be carefully examined[64]. One effective and novel approach in the virus-mediated treatment of cancer is the use of conditionally replicating adenoviruses (CRAds), which can replicate in tumor cells but not in normal cells. Upon lysis of infected tumor cells, CRAds are released and can infect neighboring tumor cells. The current approaches targeting CRAds specifically to cancer cells were described in a recent review[65]. More recently, this field was further stimulated by the clinical report of Breitbach et al[66] who constructed a multi-mechanistic cancer-targeted oncolytic poxvirus and successfully applied it to patients with cancers. However, anti-viral immunity may theoretically attenuate the efficiency of viral vector-mediated therapy. As described in the following section, MSC-mediated gene therapy has unique advantages especially in terms of tumor-targeting selections.

The greatest benefit of MSCs in clinical application is their suitability for autologous transplantation. Autotransplantation of MSCs has been used in a numerous clinical studies, most of most of them in regenerative medicine applications, such as myocardial infarction[67,68], traumatic brain injury[60], and liver disease[69]. MSCs also represent an advantageous cell type for allogeneic transplantation. A number of different studies have demonstrated that MSCs avoid allogeneic rejection in humans and in different animal models[70,71]. MSCs are immune-privileged, characterized by low expression of MHC-I with no expression of MHC-II and co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80, CD86 and CD40[72]. Due to their limited immunogenicity, MSCs are poorly recognized by HLA-incompatible hosts. This opens up a much broader range of uses for MSCs in transplantation, compared to cells from autologous sources only.

Pre-determination of the sensitivity of particular carcinoma to any given anticancer agents is a critical step in developing personalized medicine. During ex vivo expansion, MSCs can be engineered with a variety of anticancer agents and assessed in vitro. Transwell co-culture and/or real-time monitoring techniques can be applied to this detection. The cells isolated from clinical tumor biopsy are the most practically meaningful targets. Once a sensitive anticancer agent is selected, engineered MSCs can be prepared on a large scale for the treatment.

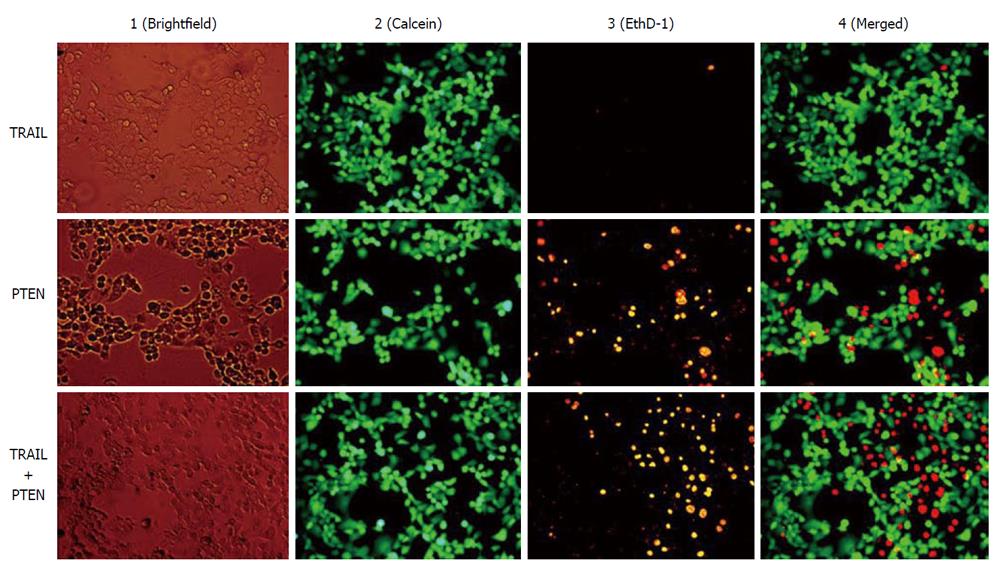

In addition to the therapeutic specificity of anticancer agents, the development of drug resistance of tumor cells is another factor contributing to inefficient cancer therapy. Since the beginning of cancer chemotherapy the frequent lack of drug response in solid tumors has been a major problem. In nearly 50% of all cancer cases, resistance to chemotherapy already exists before drug treatment starts (intrinsic resistance), and in a large proportion of remaining cases drug resistance develops during the treatment (acquired resistance)[73]. The mechanisms contributing to multidrug resistance phenotype and the challenges facing molecular targeted therapy were discussed in a recent review[74]. MSC-based cancer therapy is capable of providing multiple anticancer agents synchronously, which may potentiate therapeutic efficiency. For example, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) has gained attention in cancer gene therapy because of its capacity to induce apoptosis specifically in tumor cells. Cancer specificity is determined by the differential expression of death receptors (DR4 and DR5). Dominant expression of DR4 and/or DR5 is a determinant factor for the sensitivity of target tumor cells to TRAIL. The expression of death receptors varies with tumor type and stage as well as the therapy utilized, and the sensitivity of tumor cells to TRAIL is not particularly consistent even under apparently identical conditions[75,76]. Recent work of our group demonstrates that TRAIL-insensitive Panc-1 cell can be suppressed by transducing a death receptor-independent anticancer gene phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) (Figure 1). PTEN is a phosphatidylinositol phosphatate phosphatase and is frequently inactivated in human cancers[77]. Loss of PTEN function is associated with constitutive survival signaling through the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinas/Akt pathway. PTEN has also been demonstrated to sensitize tumor cells to death receptor-mediated apoptosis induced by TRAIL[78,79] and non-receptor mediated apoptosis induced by a kinase inhibitor staurosporine and chemotherapeutic agents mitoxantrone and etoposide[78]. The MSC-mediated therapeutic spectrum can be dramatically broadened by using multiple anticancer gene-engineered MSCs, and theoretically, a synergistic effect can be achieved via application of multiple anticancer agents simultaneously.

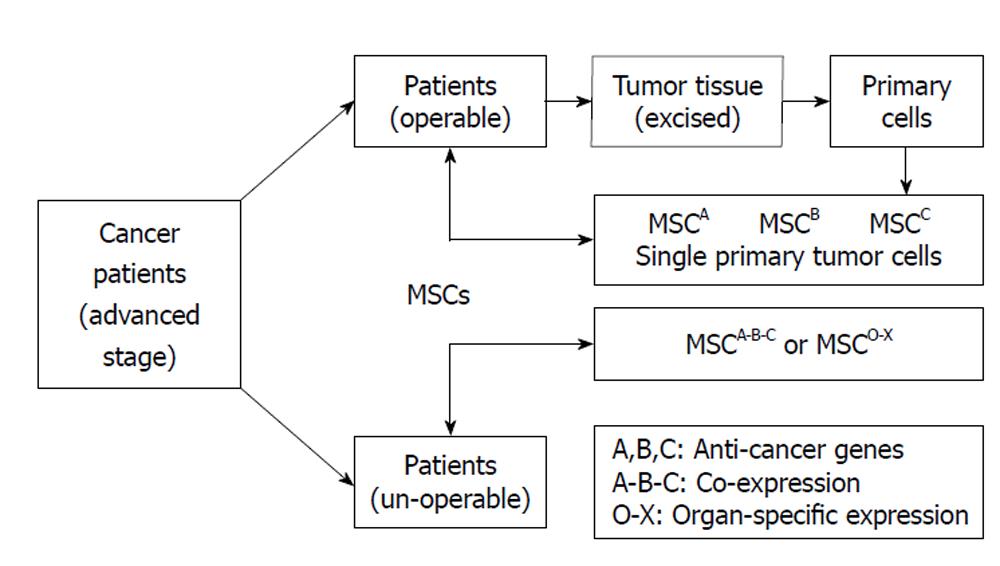

MSCs can be acquired from the patients’ own body, quickly expanded in vitro and easily transduced with expression vectors. The exhibition of the powerful tumor-directed migration capacity of MSCs makes them suitable for use in anticancer therapies. Anticancer-engineered MSCs could be eventually used as an alterative treatment for cancer patients without the concern of rejection or other ethical problems. Since there is a great deal of variation amongst the cancer patient population with respect to degree of carcinogenic differentiation and preparation of human MSCs, it is unlikely that a single fixed therapeutic model will be found that would successfully perform on different types of cancers. In order to translate bench research into real clinical applications, it will be necessary to develop a specific personalized treatment for each individual patient. Figure 2 illustrated putative personalized strategy with anticancer gene-engineered MSCs.

There is a pressing clinical demand for more efficient remedies to replace existing symptomatic anticancer therapies. The extensive achievements of MSCs and anticancer agent studies have laid the foundation for the exploitation of MSC-based cancer therapies. MSCs possess powerful capabilities of tumor-directed migration and incorporation, giving them the potential of acting as optimal vehicles to deliver anticancer agents. Although MSCs have both positive and negative effects on tumor progression, profound anticancer effects have been demonstrated by using apropriately engineered MSCs. MSC-mediated anticancer therapy relies on tumor-specific selectivity provided by MSCs and MSC-carried anticancer agents. Homed directly at the tumor microenvironment, engineered MSCs are able to express and/or release anticancer agents constantly, acting on the adjacent tumor cells. To date, however, almost all of the available findings are confined to cell culture and/or animal cancer models, and more well-designed pre-clinical studies are definitely required before applying this strategy to real clinical settings.

In conclusion, the recent progress in both stem cell and anticancer gene studies has great potential for exploitation in new efficient cancer therapies. The combination of human MSCs and specific anticancer genes can selectively act upon targeted tumor cells. Further translational studies could lead to novel and effective treatments for cancer. Hopefully, the utilization of dual-targeted anticancer gene-engineered MSCs will be of great benefit to future cancer patients.

The authors are grateful to Crystal Robertson for her assistance in preparing the manuscript and English proof reading.

Peer reviewers: Margherita Maioli, PhD, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Division of Biochemistry, University of Sassari, Sassari 07100, Italy; Nishit Pancholi, MS, Hektoen Institute of Medicine, Chicago, IL 60612, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10002] [Cited by in RCA: 10453] [Article Influence: 696.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Friedenstein AJ, Piatetzky-Shapiro II, Petrakova KV. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1966;16:381-390. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Friedenstein AJ, Petrakova KV, Kurolesova AI, Frolova GP. Heterotopic of bone marrow. Analysis of precursor cells for osteogenic and hematopoietic tissues. Transplantation. 1968;6:230-247. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Väänänen HK. Mesenchymal stem cells. Ann Med. 2005;37:469-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:726-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2360] [Cited by in RCA: 2697] [Article Influence: 168.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:641-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3539] [Cited by in RCA: 3298] [Article Influence: 97.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bexell D, Scheding S, Bengzon J. Toward brain tumor gene therapy using multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell vectors. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1067-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15372] [Cited by in RCA: 15195] [Article Influence: 584.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Le Blanc K, Pittenger M. Mesenchymal stem cells: progress toward promise. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:36-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fiorina P, Jurewicz M, Augello A, Vergani A, Dada S, La Rosa S, Selig M, Godwin J, Law K, Placidi C. Immunomodulatory function of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in experimental autoimmune type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2009;183:993-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nauta AJ, Fibbe WE. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. Blood. 2007;110:3499-3506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1289] [Cited by in RCA: 1334] [Article Influence: 74.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Dai LJ, Moniri MR, Zeng ZR, Zhou JX, Rayat J, Warnock GL. Potential implications of mesenchymal stem cells in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:8-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Loebinger MR, Janes SM. Stem cells as vectors for antitumour therapy. Thorax. 2010;65:362-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kucerova L, Altanerova V, Matuskova M, Tyciakova S, Altaner C. Adipose tissue-derived human mesenchymal stem cells mediated prodrug cancer gene therapy. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6304-6313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Morizono K, De Ugarte DA, Zhu M, Zuk P, Elbarbary A, Ashjian P, Benhaim P, Chen IS, Hedrick MH. Multilineage cells from adipose tissue as gene delivery vehicles. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:59-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mishra PJ, Mishra PJ, Glod JW, Banerjee D. Mesenchymal stem cells: flip side of the coin. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1255-1258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nakamura K, Ito Y, Kawano Y, Kurozumi K, Kobune M, Tsuda H, Bizen A, Honmou O, Niitsu Y, Hamada H. Antitumor effect of genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells in a rat glioma model. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1155-1164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1650-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3033] [Cited by in RCA: 3096] [Article Influence: 79.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Loebinger MR, Kyrtatos PG, Turmaine M, Price AN, Pankhurst Q, Lythgoe MF, Janes SM. Magnetic resonance imaging of mesenchymal stem cells homing to pulmonary metastases using biocompatible magnetic nanoparticles. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8862-8867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sasportas LS, Kasmieh R, Wakimoto H, Hingtgen S, van de Water JA, Mohapatra G, Figueiredo JL, Martuza RL, Weissleder R, Shah K. Assessment of therapeutic efficacy and fate of engineered human mesenchymal stem cells for cancer therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4822-4827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sonabend AM, Ulasov IV, Tyler MA, Rivera AA, Mathis JM, Lesniak MS. Mesenchymal stem cells effectively deliver an oncolytic adenovirus to intracranial glioma. Stem Cells. 2008;26:831-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yang B, Wu X, Mao Y, Bao W, Gao L, Zhou P, Xie R, Zhou L, Zhu J. Dual-targeted antitumor effects against brainstem glioma by intravenous delivery of tumor necrosis factor-related, apoptosis-inducing, ligand-engineered human mesenchymal stem cells. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:610-24; discussion 624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khakoo AY, Pati S, Anderson SA, Reid W, Elshal MF, Rovira II, Nguyen AT, Malide D, Combs CA, Hall G. Human mesenchymal stem cells exert potent antitumorigenic effects in a model of Kaposi's sarcoma. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1235-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 587] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kidd S, Spaeth E, Dembinski JL, Dietrich M, Watson K, Klopp A, Battula VL, Weil M, Andreeff M, Marini FC. Direct evidence of mesenchymal stem cell tropism for tumor and wounding microenvironments using in vivo bioluminescent imaging. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2614-2623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 532] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Patel SA, Meyer JR, Greco SJ, Corcoran KE, Bryan M, Rameshwar P. Mesenchymal stem cells protect breast cancer cells through regulatory T cells: role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2010;184:5885-5894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Menon LG, Picinich S, Koneru R, Gao H, Lin SY, Koneru M, Mayer-Kuckuk P, Glod J, Banerjee D. Differential gene expression associated with migration of mesenchymal stem cells to conditioned medium from tumor cells or bone marrow cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:520-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kidd S, Caldwell L, Dietrich M, Samudio I, Spaeth EL, Watson K, Shi Y, Abbruzzese J, Konopleva M, Andreeff M. Mesenchymal stromal cells alone or expressing interferon-beta suppress pancreatic tumors in vivo, an effect countered by anti-inflammatory treatment. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:615-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zischek C, Niess H, Ischenko I, Conrad C, Huss R, Jauch KW, Nelson PJ, Bruns C. Targeting tumor stroma using engineered mesenchymal stem cells reduces the growth of pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;250:747-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Studeny M, Marini FC, Champlin RE, Zompetta C, Fidler IJ, Andreeff M. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells as vehicles for interferon-beta delivery into tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3603-3608. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Salem HK, Thiemermann C. Mesenchymal stromal cells: current understanding and clinical status. Stem Cells. 2010;28:585-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 607] [Cited by in RCA: 692] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Maestroni GJ, Hertens E, Galli P. Factor(s) from nonmacrophage bone marrow stromal cells inhibit Lewis lung carcinoma and B16 melanoma growth in mice. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:663-667. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Ohlsson LB, Varas L, Kjellman C, Edvardsen K, Lindvall M. Mesenchymal progenitor cell-mediated inhibition of tumor growth in vivo and in vitro in gelatin matrix. Exp Mol Pathol. 2003;75:248-255. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Qiao L, Zhao TJ, Wang FZ, Shan CL, Ye LH, Zhang XD. NF-kappaB downregulation may be involved the depression of tumor cell proliferation mediated by human mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:333-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, Sullivan A, Brooks MW, Bell GW, Richardson AL, Polyak K, Tubo R, Weinberg RA. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2555] [Cited by in RCA: 2441] [Article Influence: 135.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Coffelt SB, Marini FC, Watson K, Zwezdaryk KJ, Dembinski JL, LaMarca HL, Tomchuck SL, Honer zu Bentrup K, Danka ES, Henkle SL. The pro-inflammatory peptide LL-37 promotes ovarian tumor progression through recruitment of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3806-3811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Djouad F, Plence P, Bony C, Tropel P, Apparailly F, Sany J, Noël D, Jorgensen C. Immunosuppressive effect of mesenchymal stem cells favors tumor growth in allogeneic animals. Blood. 2003;102:3837-3844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 876] [Cited by in RCA: 836] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ehtesham M, Kabos P, Kabosova A, Neuman T, Black KL, Yu JS. The use of interleukin 12-secreting neural stem cells for the treatment of intracranial glioma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5657-5663. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Pisati F, Belicchi M, Acerbi F, Marchesi C, Giussani C, Gavina M, Javerzat S, Hagedorn M, Carrabba G, Lucini V. Effect of human skin-derived stem cells on vessel architecture, tumor growth, and tumor invasion in brain tumor animal models. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3054-3063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Moore XL, Lu J, Sun L, Zhu CJ, Tan P, Wong MC. Endothelial progenitor cells' "homing" specificity to brain tumors. Gene Ther. 2004;11:811-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Xin H, Kanehira M, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, Kikuchi T, Nukiwa T, Saijo Y. Targeted delivery of CX3CL1 to multiple lung tumors by mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1618-1626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Cavarretta IT, Altanerova V, Matuskova M, Kucerova L, Culig Z, Altaner C. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells expressing prodrug-converting enzyme inhibit human prostate tumor growth. Mol Ther. 2010;18:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Miletic H, Fischer Y, Litwak S, Giroglou T, Waerzeggers Y, Winkeler A, Li H, Himmelreich U, Lange C, Stenzel W. Bystander killing of malignant glioma by bone marrow-derived tumor-infiltrating progenitor cells expressing a suicide gene. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1373-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ren C, Kumar S, Chanda D, Chen J, Mountz JD, Ponnazhagan S. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells producing interferon-alpha in a mouse melanoma lung metastasis model. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2332-2338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Sato H, Kuwashima N, Sakaida T, Hatano M, Dusak JE, Fellows-Mayle WK, Papworth GD, Watkins SC, Gambotto A, Pollack IF. Epidermal growth factor receptor-transfected bone marrow stromal cells exhibit enhanced migratory response and therapeutic potential against murine brain tumors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005;12:757-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Ling X, Marini F, Konopleva M, Schober W, Shi Y, Burks J, Clise-Dwyer K, Wang RY, Zhang W, Yuan X. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Overexpressing IFN-β Inhibit Breast Cancer Growth and Metastases through Stat3 Signaling in a Syngeneic Tumor Model. Cancer Microenviron. 2010;3:83-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Gunnarsson S, Bexell D, Svensson A, Siesjö P, Darabi A, Bengzon J. Intratumoral IL-7 delivery by mesenchymal stromal cells potentiates IFNgamma-transduced tumor cell immunotherapy of experimental glioma. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;218:140-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chen X, Lin X, Zhao J, Shi W, Zhang H, Wang Y, Kan B, Du L, Wang B, Wei Y. A tumor-selective biotherapy with prolonged impact on established metastases based on cytokine gene-engineered MSCs. Mol Ther. 2008;16:749-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Xu G, Jiang XD, Xu Y, Zhang J, Huang FH, Chen ZZ, Zhou DX, Shang JH, Zou YX, Cai YQ. Adenoviral-mediated interleukin-18 expression in mesenchymal stem cells effectively suppresses the growth of glioma in rats. Cell Biol Int. 2009;33:466-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kanehira M, Xin H, Hoshino K, Maemondo M, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Nukiwa T, Saijo Y. Targeted delivery of NK4 to multiple lung tumors by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14:894-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Menon LG, Kelly K, Yang HW, Kim SK, Black PM, Carroll RS. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells expressing S-TRAIL as a cellular delivery vehicle for human glioma therapy. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2320-2330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kim SM, Lim JY, Park SI, Jeong CH, Oh JH, Jeong M, Oh W, Park SH, Sung YC, Jeun SS. Gene therapy using TRAIL-secreting human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells against intracranial glioma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9614-9623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Loebinger MR, Eddaoudi A, Davies D, Janes SM. Mesenchymal stem cell delivery of TRAIL can eliminate metastatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4134-4142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Grisendi G, Bussolari R, Cafarelli L, Petak I, Rasini V, Veronesi E, De Santis G, Spano C, Tagliazzucchi M, Barti-Juhasz H. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells as stable source of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand delivery for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3718-3729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Mueller LP, Luetzkendorf J, Widder M, Nerger K, Caysa H, Mueller T. TRAIL-transduced multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (TRAIL-MSC) overcome TRAIL resistance in selected CRC cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Gene Ther. 2011;18:229-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Luetzkendorf J, Mueller LP, Mueller T, Caysa H, Nerger K, Schmoll HJ. Growth inhibition of colorectal carcinoma by lentiviral TRAIL-transgenic human mesenchymal stem cells requires their substantial intratumoral presence. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2292-2304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Mohr A, Albarenque SM, Deedigan L, Yu R, Reidy M, Fulda S, Zwacka RM. Targeting of XIAP combined with systemic mesenchymal stem cell-mediated delivery of sTRAIL ligand inhibits metastatic growth of pancreatic carcinoma cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:2109-2120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Pulkkanen KJ, Yla-Herttuala S. Gene therapy for malignant glioma: current clinical status. Mol Ther. 2005;12:585-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Uchibori R, Okada T, Ito T, Urabe M, Mizukami H, Kume A, Ozawa K. Retroviral vector-producing mesenchymal stem cells for targeted suicide cancer gene therapy. J Gene Med. 2009;11:373-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kucerova L, Matuskova M, Pastorakova A, Tyciakova S, Jakubikova J, Bohovic R, Altanerova V, Altaner C. Cytosine deaminase expressing human mesenchymal stem cells mediated tumour regression in melanoma bearing mice. J Gene Med. 2008;10:1071-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Zhang ZX, Guan LX, Zhang K, Zhang Q, Dai LJ. A combined procedure to deliver autologous mesenchymal stromal cells to patients with traumatic brain injury. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:134-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Nakamizo A, Marini F, Amano T, Khan A, Studeny M, Gumin J, Chen J, Hentschel S, Vecil G, Dembinski J. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of gliomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3307-3318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 780] [Cited by in RCA: 808] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Komarova S, Kawakami Y, Stoff-Khalili MA, Curiel DT, Pereboeva L. Mesenchymal progenitor cells as cellular vehicles for delivery of oncolytic adenoviruses. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:755-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Xin H, Sun R, Kanehira M, Takahata T, Itoh J, Mizuguchi H, Saijo Y. Intratracheal delivery of CX3CL1-expressing mesenchymal stem cells to multiple lung tumors. Mol Med. 2009;15:321-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Nair V. Retrovirus-induced oncogenesis and safety of retroviral vectors. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2008;10:431-438. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Jiang G, Xin Y, Zheng JN, Liu YQ. Combining conditionally replicating adenovirus-mediated gene therapy with chemotherapy: a novel antitumor approach. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:263-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Breitbach CJ, Burke J, Jonker D, Stephenson J, Haas AR, Chow LQ, Nieva J, Hwang TH, Moon A, Patt R. Intravenous delivery of a multi-mechanistic cancer-targeted oncolytic poxvirus in humans. Nature. 2011;477:99-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 432] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Assmus B, Honold J, Schächinger V, Britten MB, Fischer-Rasokat U, Lehmann R, Teupe C, Pistorius K, Martin H, Abolmaali ND. Transcoronary transplantation of progenitor cells after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1222-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 755] [Article Influence: 39.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Strauer BE, Brehm M, Zeus T, Bartsch T, Schannwell C, Antke C, Sorg RV, Kögler G, Wernet P, Müller HW. Regeneration of human infarcted heart muscle by intracoronary autologous bone marrow cell transplantation in chronic coronary artery disease: the IACT Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1651-1658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Dai LJ, Li HY, Guan LX, Ritchie G, Zhou JX. The therapeutic potential of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on hepatic cirrhosis. Stem Cell Res. 2009;2:16-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105:1815-1822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3271] [Cited by in RCA: 3276] [Article Influence: 156.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Götherström C, Hassan M, Uzunel M, Ringdén O. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2044] [Cited by in RCA: 2027] [Article Influence: 96.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Immunoregulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2566-2573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Lippert TH, Ruoff HJ, Volm M. Current status of methods to assess cancer drug resistance. Int J Med Sci. 2011;8:245-253. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Shekhar MP. Drug resistance: challenges to effective therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:613-623. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Jeong M, Kwon YS, Park SH, Kim CY, Jeun SS, Song KW, Ko Y, Robbins PD, Billiar TR, Kim BM. Possible novel therapy for malignant gliomas with secretable trimeric TRAIL. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Xu J, Zhou JY, Wei WZ, Wu GS. Activation of the Akt survival pathway contributes to TRAIL resistance in cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Chalhoub N, Baker SJ. PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:127-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 996] [Cited by in RCA: 1141] [Article Influence: 71.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Yuan XJ, Whang YE. PTEN sensitizes prostate cancer cells to death receptor-mediated and drug-induced apoptosis through a FADD-dependent pathway. Oncogene. 2002;21:319-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Opel D, Westhoff MA, Bender A, Braun V, Debatin KM, Fulda S. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibition broadly sensitizes glioblastoma cells to death receptor- and drug-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6271-6280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |