Published online Mar 26, 2025. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v17.i3.103560

Revised: January 16, 2025

Accepted: February 17, 2025

Published online: March 26, 2025

Processing time: 118 Days and 17 Hours

Exosomes (Exos) are extracellular vesicles secreted by cells and serve as crucial mediators of intercellular communication. They play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis and progression of various diseases and offer promising avenues for therapeutic interventions. Exos derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have significant immunomodulatory properties. They effectively regulate immune responses by modulating both innate and adaptive immunity. These Exos can inhibit excessive inflammatory responses and promote tissue repair. Moreover, they participate in antigen presentation, which is essential for activating immune responses. The cargo of these Exos, including ligands, proteins, and microRNAs, can suppress T cell activity or enhance the population of immunosuppressive cells to dampen the immune response. By inhibiting lymphocyte proliferation, acting on macrophages, and increasing the population of regulatory T cells, these Exos contribute to maintaining immune and metabolic homeostasis. Furthermore, they can activate immune-related signaling pathways or serve as vehicles to deliver microRNAs and other bioactive substances to target tumor cells, which holds potential for immunotherapy applications. Given the immense therapeutic potential of MSC-derived Exos, this review comprehensively explores their mechanisms of immune regulation and therapeutic applications in areas such as infection control, tumor suppression, and autoimmune disease management. This article aims to provide valuable insights into the mechanisms behind the actions of MSC-derived Exos, offering theoretical references for their future clinical utilization as cell-free drug preparations.

Core Tip: Exosomes (Exos) are extracellular vesicles secreted by cells, and they serve as crucial mediators of intercellular communication, playing a pivotal role in the pathogenesis, progression, and therapeutic interventions for various diseases. Given the immense therapeutic potential of Exos derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC-Exos), this review article comprehensively explores mechanisms underlying their immune regulation as well as their therapeutic applications in infection control measures and tackling tumors or autoimmune diseases among others. This article aims to provide valuable insights into further investigations regarding the mechanism behind MSC-Exo actions while offering theoretical references for future clinical utilization of MSC-Exos as cell-free drug preparations.

- Citation: Yi YF, Fan ZQ, Liu C, Ding YT, Chen Y, Wen J, Jian XH, Li YF. Immunomodulatory effects and clinical application of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells. World J Stem Cells 2025; 17(3): 103560

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v17/i3/103560.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v17.i3.103560

Exosomes (Exos) were first discovered in 1983 as 50-nm vesicles released by reticulocytes carrying transferrin receptors extracellularly[1]. Since then, the understanding of the mechanisms and functions of Exos has exponentially expanded[2]. Exos are extracellular vesicles (EVs) with a diameter ranging from 40 to 160 nm (mean, ~100 nm) that originate from endosomes[3]. Depending on the specific cell type that they derive from, Exos contain various components such as DNA, RNA, lipids, metabolites, cytoplasmic contents, and cell-surface proteins[4]. The exact physiological role of Exo production by cells remains elusive and requires further investigation[5]. Due to their functional and targeted nature as cellular constituents, Exos play a crucial role in intercellular communication[6]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a class of adult stem cells first identified by Friedenstein in mouse bone marrow and characterized by their multilineage differentiation potential. Caplan subsequently coined the term “mesenchymal stem cells”[7], although their definitive stem cell properties have yet to be rigorously demonstrated in vivo[8]. MSCs have been shown to originate from perivascular and pericytic progenitors in almost all tissues[9]. These cells possess trilineage differentiation potential, enabling them to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes. They express positive cell surface markers CD90, CD105, and CD73, while lacking CD45, CD34, CD14, CD79a, and HLA-DR[10]. Under specific conditions, MSCs can also differentiate into other cell types, such as neurons and cardiomyocytes[11].

MSCs possess a certain self-renewal capacity and can be propagated through multiple generations in vitro while maintaining their phenotype and differentiation potential[12]. They secrete a variety of cytokines and growth factors, which inhibit the proliferation of B cells and T cells, suppress monocyte maturation, and promote the generation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and M2 macrophages[13]. These characteristics endow MSCs with immunomodulatory functions, forming the foundation for their application in treating various immune-related diseases. The primary clinical value of MSCs appears to stem from secreted EVs (including Exos) and a range of cytokines and growth factors[14]. The immunoregulatory effects of these secreted Exos have demonstrated therapeutic potential in numerous clinical studies. These studies encompass conditions such as myocardial infarction, stroke, graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Crohn’s disease, acute lung injury, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver cirrhosis, multiple sclerosis (MS), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and diabetes[15].

A substantial body of evidence suggests that MSCs exert their immunomodulatory functions primarily through paracrine pathways, particularly via Exos[16]. Exos derived from MSCs (MSC-Exos) exhibit comparable biological activities to MSCs and possess several advantageous characteristics such as rapid passage through capillaries, inherent stability, and robust information transfer capacity compared to MSCs[17]. Furthermore, the utilization of Exos can circumvent issues associated with ectopic osteogenesis, tumor formation, pulmonary capillary blockade, and immune rejection commonly encountered in cell therapy. The low immunogenicity and high stability of Exos make them a promising alternative strategy for cell therapy[18]. Notably, Exos play pivotal roles in inflammation, tumors, and autoimmune diseases, as well as graft rejection[19]. MSC-Exos have achieved several significant breakthroughs in recent years. Research has demonstrated their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, exert neuroprotective effects, and facilitate nerve regeneration. This approach offers novel insights and potential strategies for the treatment of brain injuries, stroke, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. MSC-Exos play a crucial role in immune regulation by modulating immune responses and mitigating inflammation, which holds potential for treating autoimmune diseases such as RA and SLE[20,21]. Additionally, MSC-Exos are being explored for cancer treatment, including metastatic cancers. Studies have demonstrated their utility as drug delivery vectors to enhance the efficacy of anticancer drugs while minimizing side effects. In cardiovascular disease and skin wound repair, MSC-Exos have exhibited the capacity to promote tissue repair and regeneration, supporting myocardial cell survival and functional recovery, as well as accelerating skin wound healing[22]. Recent technological advancements have improved the production efficiency and functional customization of MSC-Exos. For instance, genetic engineering and optimized culture conditions have enhanced specific therapeutic properties of Exos[23]. These innovations highlight the significant potential of MSC-Exos as a novel biologic therapeutic tool. Several clinical studies on Exos have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), including investigations into the molecular mechanisms of Exos in melanoma pathogenesis (FDA lot number: NCT02310451), the clinical correlation of glioma exosomal molecular abnormalities (FDA batch No.: NCT06116903), and the effect of Exo administration in preventing early leakage in patients with low anterior resection rectal cancer (FDA Lot No.: NCT06536712). As research progresses, the application prospects for MSC-Exos will continue to broaden[24]. Therefore, this article comprehensively reviews the mechanisms underlying immune regulation by MSC-Exos along with their therapeutic applications in infection control, tumor management, and autoimmune diseases. This article serves as a valuable reference for further investigations into the mechanisms governing MSC-Exo function while providing theoretical support for future clinical implementation of MSC-Exos as cell-free drug preparations.

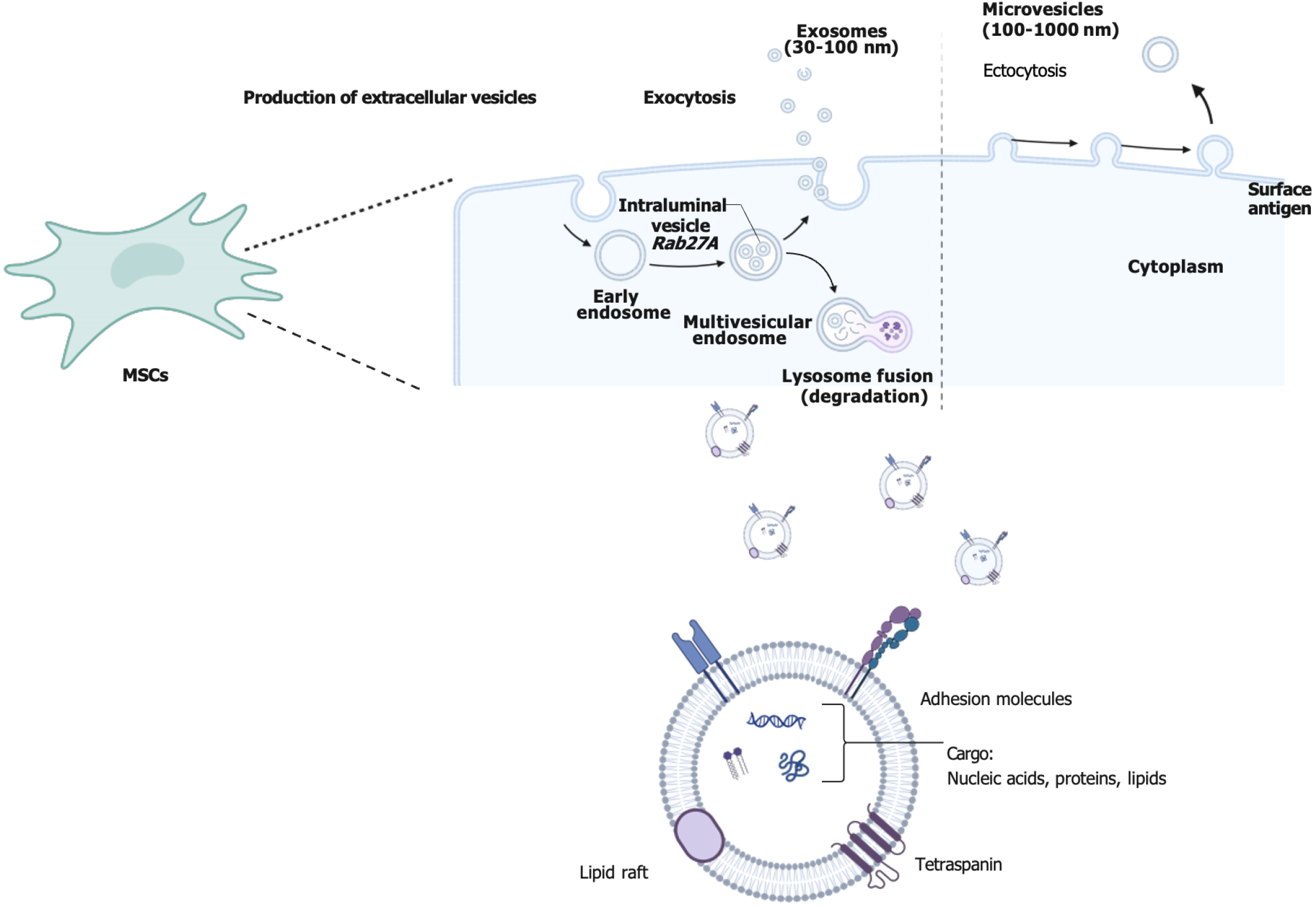

MSCs can be isolated from various tissues, and Exos derived from different tissues and cell types may carry distinct biomolecules that confer unique immune properties and potential therapeutic applications. MSC-Exos exhibit significant immunomodulatory effects, capable of downregulating inflammatory responses and promoting immune tolerance. They are widely utilized in the treatment of inflammatory diseases and autoimmune conditions such as SLE and RA, as well as in promoting tissue repair and regeneration[25]. Exos derived from tumor cells are frequently utilized as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for developing novel cancer immunotherapies and diagnostic approaches[26]. Exos secreted by cardiomyocytes can modulate cardiac inflammatory responses, enhance cardiomyocyte survival, and facilitate cardiac tissue regeneration. In studies of myocardial infarction and other cardiovascular diseases, these Exos have demonstrated potential therapeutic benefits[22]. Exos from adipose-derived stem cells are employed to treat conditions such as impaired wound healing and skin disorders, promoting the regeneration process. Exos derived from neural stem cells exhibit neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties, provide neurotrophic support, and regulate immune responses within the nervous system, showing promise in treating neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s[27,28]. These cells can be derived from diverse tissues depending on their origin. Exos are small vesicles released into the extracellular space following fusion between intracellular multivesicular bodies and the cellular membrane[29]. This secretory process involves recognition and trafficking of specific proteins and lipids[30], such as the ESCRT system (endosomal sorting complex)[31]. Exos typically range in size from 40 to 160 nm[32] with a lipid bilayer membrane structure that provides stability and protection[33], conferring them potential therapeutic utility due to their stable structure and precise targeting ability[34,35]. Exos transport distinct proteins and RNA molecules that mirror the cellular origin and exert an impact on the functionality of recipient cells[36]. They assume pivotal roles in intercellular communication by transferring informational molecules to regulate immune response, inflammation, and tissue repair, among other processes[37]. Consequently, owing to their inherent structural stability and precise targeting capabilities, Exos are regarded as promising therapeutic tools[38] (Figure 1).

MSC-Exos not only express protein markers commonly found in all Exos[39], but also exhibit specific membrane surface molecules on MSCs[40]. These Exos contain bioactive molecules such as microRNAs (miRNAs), mRNA, and proteins that play a crucial role in regulating gene expression and function in target cells. Lai et al[41] first investigated the role of MSC-Exos in a mouse model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in 2010, followed by studies conducted across various disease models[42]. MSC-Exos have been shown to facilitate tissue regeneration through intercellular communication, particularly following kidney, liver, cardiovascular, and nervous system injuries[43]. By secreting Exos, MSCs modulate immune responses by reducing inflammatory factors while increasing anti-inflammatory factor levels[44]. These Exos carry miRNAs and proteins that regulate apoptotic pathways to enhance the survival of target cells and mitigate oxidative stress damage[45]. In heart disease models specifically, MSC-Exos improve cardiac function and morphology by augmenting survival signaling pathways while suppressing inflammatory responses[46]. Therefore, the clinical potential for utilizing MSC-Exos as a cell replacement therapy is extensive. However, MSC-Exos encounter several practical challenges during the isolation process. For instance, Exo production can be influenced by multiple factors such as the diversity of cell sources, variations in culture conditions, and differences in cell states. This variability introduces uncertainty in Exo yield for each isolation procedure, thereby impacting its consistent supply[47]. Addi

MSC-Exos play a pivotal role in immunomodulation, which has been associated with their capacity to influence various immune cell functions[48]. MSC-Exos possess the ability to regulate both innate and adaptive immune responses. In terms of innate immunity, they modulate the polarization and cytokine secretion of macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) through interactions with these cells, thereby suppressing inflammatory responses[49]. Specifically, MSC-Exos can attenuate inflammatory damage by polarizing macrophages towards an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype rather than a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype[50]. Concerning adaptive immunity, MSC-Exos achieve immunosuppression by regulating the activity of T cells and B cells. They inhibit the proliferation and cytotoxic functions of T cells while promoting the generation of Tregs, which are crucial for maintaining immune tolerance and preventing autoimmune diseases[51]. Through these mechanisms, MSC-Exos are capable of maintaining immune tolerance and preventing or treating autoimmune diseases. This capability is especially valuable in scenarios where excessive immune responses must be modulated in disease states such as RA and other autoimmune conditions[52]. MSC-Exos also have the ability to modulate humoral immune responses by influencing the antibody-producing function of B cells[53]. The miRNAs, proteins, and other bioactive molecules encapsulated within MSC-Exos can transmit signals between cells via various pathways including direct targeting of specific mRNAs to regulate gene expression or activation/inhibition of immune signaling pathways[54]. MiRNAs are a class of short non-coding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression. MiRNAs encapsulated in Exos can modulate protein expression levels by targeting specific mRNAs, leading to their inhibition or degradation[55]. Specific miRNAs can influence both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways. For instance, certain miRNAs can downregulate the expression of pro-inflammatory factors in M1-type macrophages, thereby promoting their transition to the M2-type (anti-inflammatory) phenotype[56]. Notably, miRNAs such as miR-223 and miR-146a alter the functional state of macrophages by affecting key signaling nodes like nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB), signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B. NF-κB plays a crucial role in the development, differentiation, and responsiveness of immune cells. Exos can modulate the function of immune cells, including T cells, B cells, and macrophages, by regulating the NF-κB pathway. Exos secreted by tumor cells can promote tumor growth and immune escape through the activation of the NF-κB pathway, whereas Exos derived from stem cells may inhibit this pathway and enhance anti-tumor immunity[57]. By modulating the NF-κB signaling pathway, Exos regulate inflammatory responses. For instance, MSC-Exos can exert anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting NF-κB activity and reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1β[58]. Cytokines within Exos directly influence immune cell behavior; for example, anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 or transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) delivered via Exos can modulate immune responses and promote immune tolerance. Additionally, membrane proteins and signaling molecules in Exos can bind to receptors on target cells, initiate intracellular signaling cascades, and regulate cellular behavior. Specific proteins within Exos can directly modulate the immune response, such as by inhibiting immune cell activation or inducing immune cell apoptosis to achieve immune regulatory effects[59]. As natural vectors for signal transduction, MSC-Exos possess significant regulatory capabilities in controlling immune system homeostasis by inhibiting excessive inflammatory responses while promoting tissue repair.

In recent years, it has been discovered that MSCs play a crucial role in intercellular communication through the secretion of Exos[45]. These Exos possess the ability to modulate immune cell function and response. Through packaging and transportation of signaling molecules, a diverse range of bioactive compounds can be encapsulated within Exos, ensuring protection against degradation while enabling specific delivery to target cells[60]. Furthermore, Exo surfaces are adorned with various membrane proteins involved in target cell recognition and binding[61]. Upon fusion with the target cell membrane, the contents of Exos are released into the cytoplasm, thereby activating relevant signaling pathways[62]. MSC-Exos exhibit an abundance of miRNAs that specifically target and regulate immune-related gene expression[63]. Certain miRNAs have demonstrated their capability to shift macrophage polarization from proinflammatory M1 phenotype towards an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype by regulating Toll-like receptor and NF-κB signaling pathways, ultimately leading to inflammation reduction[64].

Proteins present in Exos, such as cytokines and signaling proteins, have a direct impact on the functionality of target cells. Exos can deliver anti-inflammatory cytokines to inhibit the proliferation of T cells and B cells or facilitate the generation of Tregs by delivering immunomodulatory proteins. Moreover, they can transport specific signaling molecules that activate or suppress signaling pathways in target cells, thereby influencing the cellular immune response[65]. This mechanism plays a crucial role in regulating immune system homeostasis and preventing potential damage caused by excessive immune activity[66]. The utilization of MSC-Exos offers novel insights and potential applications for treating various immune-related disorders through efficient delivery of diverse immunoactive substances while modulating immune system responses (Figure 1).

Immunosuppression refers to the process of suppressing or reducing immune system activity through various mechanisms. MSC-Exos modulate cytokines, such as IL-10 and prostaglandin E2, thereby regulating macrophage polarization from a pro-inflammatory M1 to an anti-inflammatory M2 type, which reduces inflammation and promotes tissue repair[67]. The role of MSC-Exos in immune regulation is primarily towards immunosuppression rather than activation[68]. These Exos contain a variety of molecules that can regulate T cell function, including specific miRNAs and proteins that downregulate T-cell receptor signaling, and inhibit T-cell proliferation and activation, thus reducing the intensity of the immune response[69].

Exos contain specific components that can impede the maturation and antigen presentation capacity of DCs, thereby diminishing their potential to activate T cells. Consequently, this effect mitigates the hyperactive response of the immune system towards tissues or grafts[70]. Additionally, MSC-Exos exhibit inhibitory effects on B cell proliferation, differentiation, and antibody production, thus contributing to the amelioration of pathological immune responses. Furthermore, MSC-Exos possess the ability to attenuate inflammation and tissue damage by suppressing the cytotoxic activity of natural killer cells and restraining aggressive behavior within their own tissues[71]. Although Exos can effectively suppress unwanted immune responses and aid in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, prolonged immunosuppression may render the body more susceptible to infections and certain diseases[72]. This is because some protective functions of the immune system may also be compromised. Excessive immunosuppression could negatively impact the body’s immune surveillance function, thereby increasing the risk of cancer or other abnormal cell proliferation. In cases of immune suppression, this function may be weakened. Additionally, different tissues may respond variably to Exo therapy. Improper immune regulation may result in incomplete or aberrant tissue repair. Long-term treatment might lead to a decrease in Exo adaptability and efficacy. In addition, there are dosing and delivery challenges: Determining the appropriate dose to avoid excessive suppression of immune system function remains a challenge. Efficiently delivering Exos to specific target cells is also technically challenging. Therefore, when developing Exo-based therapies, thorough research and clinical trials are essential to evaluate these potential risks and ensure their safety and efficacy for long-term applications. Despite these challenges, Exos remain promising candidates for treating tumor-related diseases and immune disorders such as autoimmune diseases, transplant rejection, and inflammatory diseases (Table 1).

| Source cell | Disease | Effect | Year | Ref. |

| Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells | Acute kidney injury | Promote renal tubular epithelial cell regeneration | 2017 | [42] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Ischemic myocardium | Cardioprotection | 2015 | [43] |

| Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal/stem cell | Acute graft-versus-host disease | Prolonged the survival of acute graft-versus-host disease mice and reduced pathological damage in multiple graft-versus-host disease target organs | 2018 | [52] |

| Tumor | Colorectal cancer | Promote liver metastasis | 2020 | [53] |

| Mesenchymal stromal cells | Myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion | Attenuate myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury | 2019 | [54] |

| Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | Acute lung injury | Ameliorate LPS-induced acute lung injury | 2024 | [56] |

| M1 macrophages | Tumor | Enhance antitumor immunity to inhibit tumor growth | 2021 | [57] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Multiple sclerosis | Reduce demyelination, decrease neuroinflammation, and increase the number of regulatory T cells in the spinal cord of EAE mice | 2019 | [63] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Acquired aplastic anemia | Play a key role in immune dysregulation | 2023 | [65] |

| Hypoxic mesenchymal stem cells | Bone fracture | Promote bone fracture healing | 2020 | [66] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Osteochondral defects | Mediate cartilage repair | 2018 | [67] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis | Alleviate temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis | 2019 | [69] |

| Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | Ulcerative colitis | Alleviate ulcerative colitis | 2019 | [74] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Ischemia/reperfusion injury | Alleviate ischemia/reperfusion injury | 2019 | [78] |

| Mesenchymal stromal cells | Pulmonary fibrosis | Alleviated the core features of pulmonary fibrosis and lung inflammation | 2019 | [79] |

| Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells | Nerve injury-induced pain | Possess anti-inflammatory and neurotrophic abilities | 2019 | [80] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Intrauterine adhesion | Modify intrauterine adhesion | 2022 | [81] |

| Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Prostate cancer | Restrained prostate cancer | 2022 | [89] |

| Wharton jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Cervical cancer | As drug delivery systems for cervical cancer | 2022 | [90] |

| Olfactory ecto-mesenchymal stem cells | Murine Sjögren’s syndrome | Ameliorate murine Sjögren’s syndrome | 2021 | [96] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Autoimmune uveoretinitis | Inhibit activation of antigen-presenting cells and suppress development of T helper 1 and 17 cells | 2017 | [97] |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | Islet transplantation | Improve islet transplantation | 2016 | [103] |

| Dendritic cells | Liver transplantation | Negatively regulate CD8+ T cells via inhibition of NLRP3 | 2022 | [104] |

| Endothelial cells | ARDS | Modulate the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells through IDH2/TET pathway in ARDS | 2024 | [107] |

MSC-Exos have the ability to mitigate inflammatory responses by modulating immune reactions in inflammatory diseases. They facilitate the transportation of anti-inflammatory molecules and inhibit the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby attenuating excessive immune responses triggered by bacterial or viral infections. These Exos express multiple adhesion molecules (CD29, CD44, and CD73), enabling them to home in on injured and inflamed tissues[15]. Several studies have indicated that macrophages are the primary cellular targets of MSC-Exos for reducing colonic inflammation. The activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in colonic macrophages induced by damage-associated molecular patterns released from damaged epithelial cells leads to increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, as well as elevated levels of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-1β, nitric oxide, and chemokines involved in lymphocyte and monocyte recruitment (CCL-17 and CCL-24)[55]. Macrophages are considered pivotal cells responsible for initiating colonic inflammation[73]. Cao et al’s study demonstrated that MSC-derived EVs significantly ameliorated dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice by inducing polarization towards immunosuppressive M2 phenotype in colonic macrophages[74]. The therapeutic effect exerted by these EVs on ulcerative colitis repair seems to be associated with JAK1/STAT1/STAT6 signaling[74]. Yang et al’s findings suggested that modulation of antioxidant/oxidative balance within the affected gut is accountable for MSC-EV-induced phenotypic and functional effects on macrophages[75]. Additionally, MSC-EV treatment resulted in a reduction in the cleavage of caspases-3, -8, and -9 as well as attenuated release of damage-associated molecular patterns from damaged intestinal epithelial cells. This led to the attenuation of NF-κB signaling pathway activation in colonic macrophages and subsequently promoted the generation of an immuno

MSC-Exos exhibit a protective effect on hepatocytes in cases of acute liver injury and fibrosis. In hepatitis, MSC-Exos inhibit natural killer T cells, CD4+ T lymphocytes, and hepatic stellate cells, thereby attenuating acute liver failure and fibrosis[76]. Furthermore, they safeguard stem cells by suppressing pyroptosis, inhibiting hepatocyte death, and reducing IL-1β- and IL-18-mediated inflammation[77]. Accumulating evidence suggests that MSC-Exos can shield lung epithelial cells from reactive oxidants and proteolytic enzymes released by infiltrating neutrophils and monocytes[78]. Mansouri et al[79] demonstrated that a single intravenous injection of Exos derived from human bone marrow-derived MSC (BM-MSC) significantly mitigated bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice through modulation of the phenotype and function of alveolar macrophages. Additionally, MSC-Exos alleviate inflammation at the site of nerve injury by inhibiting microglial production of inflammatory factors (TNF-α and IL-1β) while promoting synthesis of anti-inflammatory factors (IL-10 and TGF-β)[80].

The role of MSC-Exos in tumor immunity is dual, primarily determined by the bioactive molecular composition of the Exos and their interaction with the tumor microenvironment[81]. They can deliver immunosuppressive molecules that facilitate immune evasion by tumors, while also containing specific miRNAs and proteins that potentially exert immunostimulatory effects[82], enhancing immune recognition and cytotoxicity against tumor cells. MSC-Exos possess the ability to modulate the immune balance within the tumor microenvironment and shape its characteristics[83]. Consequently, their impact on tumor immunity is intricate and multifaceted, potentially providing both anti-tumor support or promoting tumorigenesis[84]. Biswas et al[85] demonstrated in vivo that MSC-Exos upregulate programmed death-ligand 1 expression in bone marrow cells while downregulating programmed cell death-1 expression in T cells, thereby suppressing protective antitumor immunity specifically in breast cancer models. Furthermore, MSC-Exos have been shown to suppress proinflammatory responses and oxidative stress mediated by immune system cells as well as humoral factors under both in vitro and in vivo conditions, creating a conducive environment for tissue regeneration[86].

Exos derived from human adipose-derived MSCs have been shown to exert inhibitory effects on ovarian cancer cells by inducing cell cycle arrest and activating mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic signaling pathways[87]. Exo miR-187 derived from human BM-MSCs was found to suppress malignant characteristics in prostate cancer cells[88] by targeting CD276, thereby inhibiting the JAK3-STAT3-Slug pathway in PCa[89]. Exos derived from human umbilical cord MSCs were utilized for paclitaxel loading and their effect on cervical cancer cell line (HeLa) was evaluated. These Exos accelerated cancer cell death through modulation of Bax, BCL2, cleaved Caspase-3, and cleaved Caspase-9 levels, while reducing chemotherapy resistance via regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related proteins such as TGF-β and catenin-β[90]. MSC-Exos have emerged as a valuable tool for cancer suppression, exhibiting the potential to inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma progression through blockade of the C5orf66-AS1/miR-127-3p/DUSP1/ERK axis[91].

It has been observed that MSC-Exos exhibit significant inhibitory effects on various effector cells involved in both innate and adaptive immune responses. Remarkable progress has been achieved in the treatment of autoimmune disorders, such as MS, SLE, type 1 diabetes mellitus, uveitis, and RA[92]. MSC-Exos demonstrate the ability to replicate MSC functionality while surpassing the limitations associated with conventional cell therapies.

MS is the most prevalent inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS). Microglia, as the primary immune cells in the CNS, play a crucial role in maintaining tissue homeostasis under normal physiological conditions[93]. Glial cells contribute to both neurodestructive and neuroprotective functions[94]. An imbalance between M1/M2 phenotypes inhibiting neuroprotective functions can promote MS development. Isik et al[95] demonstrated that treatment with BM-MSC-Exos suppressed microglial polarization towards the M1 phenotype while promoting polarization towards the M2 phenotype, leading to secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β. Notably, BM-MSC-Exos treatment significantly ameliorated neurobehavioral symptoms of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and alleviated inflammation and demyelination within the CNS.

Uveitis, a leading cause of global visual impairment, is believed to be primarily driven by autoimmunity. Numerous studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of MSC-Exos on inflammatory ocular diseases. In autoimmune uveitis mice, retinal photoreceptors exhibited severe damage accompanied by infiltration of inflammatory cells; however, when MSC-Exos were administered via tail vein injection in autoimmune uveitis mice, their retinas resembled those of normal mice with minimal structural damage and inflammatory infiltration[96,97]. Notably, T helper 1 (Th1) and Th17 cells play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of autoimmune uveitis. Treatment with MSC-Exos resulted in significantly reduced numbers of interferon-gamma+CD4+ cells (Th1) and IL-17+CD4+ cells (Th17) compared to phosphate buffered saline-treated mice[98]. These findings suggest that MSC-Exos possess the ability to suppress the development of autoimmune uveitis through inhibition of Th1 and Th17 cell responses.

RA is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by synovial hyperplasia and immune-cell infiltration, leading to joint destruction[99]. Studies have found that exosomal miRNAs also play an important role in alleviating the development of RA. MSC-Exos expressing miRNA-150-5p reduced the migration and invasion of RA fibroblast-like synoviocytes and downregulated human umbilical vein endothelial cell tube formation by targeting matrix metalloproteinase 14 and vascular endothelial growth factor[100]. MSC-EV provides new insights into the treatment of RA and may provide new opportunities and strategies for the treatment of this autoimmune disease. SLE is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by immune inflammation and multiple organ damage. The pathogenesis of SLE is extremely complex. With the help of follicular helper T (Tfh) cells, antinuclear antibodies are produced, leading to the deposition of immune complexes in important organs. It has been found that the infusion of human BM-MSCs into a mouse model of lupus nephritis improved the survival of mice and alleviated the clinical symptoms of glomerulonephritis by inhibiting the development of Tfh cells and reducing the levels of autoantibodies[87].

Immune rejection is a crucial factor limiting the prognosis of organ transplantation and represents an urgent problem that needs to be addressed. Previous studies have demonstrated that the inflammatory environment can influence the characteristics and expression of biomolecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids, within Exos. Conversely, stem cells can effectively modulate inflammatory responses by transferring genetic information, including miRNA, via Exos, thereby playing an immunomodulatory role in tissue repair processes. Exosomal miRNAs serve as key regulators of islet cell function encompassing insulin expression, processing, and secretion. These exosomal miRNAs act as valuable biomarkers for assessing islet cell function and survival with significant implications for the outcome of islet transplantation[101]. Furthermore, they may be closely associated with vascular remodeling and immune regulation following islet trans

Currently, the direct application of MSC-Exos in organ transplantation indicates a promising potential for MSCs in the field of organ transplantation. Graft-infiltrating DCs and CD8+ T lymphocytes play crucial roles in immune regulation following liver transplantation (LT). Exos also emerge as a significant factor involved in transplantation immunity. Exos derived from CD80+ DCs negatively regulate CD8 T cells by suppressing nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 expression, thereby playing an essential role in attenuating acute LT rejection. These findings unveil a novel function of Exos derived from CD80+ DCs associated with the induction of LT tolerance[104].

MSCs have been extensively utilized in cell therapy due to their potent immunomodulatory and regenerative properties[105]. The paracrine activity of MSCs, particularly the production of various factors through EVs, notably Exos, has been demonstrated as a crucial determinant of their primary efficacy after infusion[106]. MSC-Exos possess significant advantages over MSCs themselves and effectively mitigate adverse side effects such as infusion-related toxicity[107]. Consequently, MSC-Exos are emerging as a promising cell-free therapeutic tool with an increasing number of clinical studies evaluating their therapeutic efficacy in diverse diseases[48]. MSC-Exos exhibit immense potential for clinical application as cell-free agents[108].

MSC-Exos from diverse sources exhibit conserved biological functions; however, they may also display functional disparities[109]. For instance, adipose tissue-derived MSC-Exos demonstrate superior angiogenic capacity compared to those derived from bone marrow[110]. Conversely, BM-MSC-Exos possess immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting interferon-gamma secretion in T cells[111]. The route of administration is another crucial factor influencing the therapeutic efficacy of MSC-Exos, with various routes being evaluated. Although intravenous injection remains the most commonly employed route in preclinical studies[112], alternative approaches such as intraperitoneal and subcutaneous administration result in enhanced accumulation of MSC-Exos within organs like the pancreas[113].

MSC-Exos were evaluated as therapeutic agents for various conditions, including acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal disease, GvHD, osteoarthritis (OA), stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and type 1 diabetes[46].

In neoplastic diseases, MSC-Exos, as natural nanocarriers, can serve as effective delivery vehicles for anticancer drugs and gene therapy tools such as small interfering RNA or miRNA, directly targeting cancer cells. This approach enhances treatment precision and mitigates the side effects associated with conventional chemotherapy. By modulating immune cells within the tumor microenvironment, MSC-Exos can augment the immune system’s ability to recognize and attack tumors. Additionally, MSC-Exos can transport anti-tumor molecules that inhibit tumor cell proliferation or induce apoptosis[114]. Chronic kidney diseases are progressive and irreversible disorders that occur when renal function declines below a certain threshold[115]. Progressive tubulointerstitial fibrosis is a common characteristic of end-stage renal disease caused by chronic kidney disease. Nassar et al[116] utilized umbilical cord blood MSC-Exos to ameliorate the progression of the disease. The umbilical cord blood MSC-Exos group exhibited significant improvements in glo

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is a potentially life-saving treatment for patients with hematological malignancies. One of the most serious complications associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is acute or chronic GvHD. A study utilized Exos derived from bone marrow MSCs in patients with GvHD, resulting in reduced secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and significant improvement in symptoms, including a reduction in diarrhea and inhibition of skin and mucosal GvHD within 14 days. However, it should be noted that one patient died of pneumonia seven months after treatment. Nevertheless, these results are promising and demonstrate potential efficacy in the treatment of GvHD[118].

Exos derived from MSCs in infectious diseases mitigate tissue damage caused by excessive immune responses through immune regulation. These Exos can transport antibacterial molecules or regulatory factors that either directly exert antibacterial effects or enhance the body’s innate immunity, thereby enabling a more effective combat against pathogens[119]. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a respiratory disease caused by the coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, which was discovered in 2020[120]. Inhalation of Exos is believed to reduce inflammation and lung injury while inducing regenerative processes, suggesting a potential therapeutic role in treating COVID-19. In a clinical study using BM-MSC-Exos, lymphopenia significantly improved and CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells increased following MSC-Exos injection, indicating the immunomodulatory effects as the therapeutic mechanism of MSC-Exos[121]. Therefore, the authors consider MSC-Exos to hold promise as a treatment for COVID-19.

In autoimmune diseases, MSC-Exos can restore immune homeostasis and mitigate disease symptoms by suppressing hyperactive immune cells, including T cells and B cells, and promoting the generation of Tregs. The bioactive molecules within these Exos can attenuate chronic inflammatory responses in various autoimmune conditions, thereby alleviating symptoms associated with diseases such as arthritis and SLE[118]. OA is an arthritic condition affecting joints that leads to pain and stiffness. BM-MSC-Exos have been investigated as a therapeutic agent for OA across various joints. At six months post-infusion, both Brief Pain Scale scores along with Upper Extremity Function Scale and Lower Extremity Function Scale scores demonstrated improvement following treatment with BM-MSC-Exos. These findings indicate that utilizing BM-MSC-Exos effectively improves OA joint conditions while ensuring safety[122].

MSC-Exos have the ability to regulate immune responses through various mechanisms, including modulation of both innate and adaptive immune systems, inhibition of excessive inflammatory responses, and promotion of tissue repair. They exert their effects by delivering immunoactive substances such as miRNAs and proteins directly to target cells, playing a crucial role in maintaining immune system homeostasis. Additionally, Exos play a regulatory role in inflammatory diseases, tumors, autoimmune diseases, and organ transplantation. Due to their outstanding performance in regulating inflammatory responses, inhibiting tumor growth, and promoting immune tolerance, Exos hold great therapeutic potential for various pathological conditions as a cell-free therapy tool that offers higher safety and stability compared to traditional cell therapy (Figure 2).

However, challenges remain before clinical applications can be fully realized. These challenges include the standardization and characterization of Exos, optimization of preparation processes, and determining the optimal route for administration. Additionally, long-term safety and efficacy need to be thoroughly verified. Future research must focus on bridging these gaps by developing strategies such as engineering Exos to enhance their functionality or to target specific tissues more effectively.

To address these challenges, it will be essential to innovate methods for Exo engineering, enabling precise modulation of their cargo and surface properties for targeted delivery. Techniques such as genetic modification or surface marker manipulation could be employed to direct Exos specifically to disease sites, enhancing therapeutic outcomes. Further, large-scale production techniques need to be optimized to ensure consistency and quality in Exo preparations.

More preclinical and clinical studies are necessary to advance this novel cell-free therapy into clinical use. Future studies should continue exploring the mechanisms of action, optimizing production and preparation processes, and verifying efficacy through more rigorous clinical trials. By addressing these knowledge gaps and developing robust methodologies, the application of Exos as a novel cell-free therapy in clinical treatment can be promoted. Advancing their application in regenerative medicine and other fields will require ongoing research and development to unlock their full therapeutic potential.

| 1. | Zhang L, Yu D. Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis, and immunity. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2019;1871:455-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 662] [Article Influence: 110.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Krylova SV, Feng D. The Machinery of Exosomes: Biogenesis, Release, and Uptake. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:1337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tang J, Jia X, Li Q, Cui Z, Liang A, Ke B, Yang D, Yao C. A DNA-based hydrogel for exosome separation and biomedical applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:e2303822120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin-Smith GK, Ayre DC, Bach JM, Bachurski D, Baharvand H, Balaj L, Baldacchino S, Bauer NN, Baxter AA, Bebawy M, Beckham C, Bedina Zavec A, Benmoussa A, Berardi AC, Bergese P, Bielska E, Blenkiron C, Bobis-Wozowicz S, Boilard E, Boireau W, Bongiovanni A, Borràs FE, Bosch S, Boulanger CM, Breakefield X, Breglio AM, Brennan MÁ, Brigstock DR, Brisson A, Broekman ML, Bromberg JF, Bryl-Górecka P, Buch S, Buck AH, Burger D, Busatto S, Buschmann D, Bussolati B, Buzás EI, Byrd JB, Camussi G, Carter DR, Caruso S, Chamley LW, Chang YT, Chen C, Chen S, Cheng L, Chin AR, Clayton A, Clerici SP, Cocks A, Cocucci E, Coffey RJ, Cordeiro-da-Silva A, Couch Y, Coumans FA, Coyle B, Crescitelli R, Criado MF, D'Souza-Schorey C, Das S, Datta Chaudhuri A, de Candia P, De Santana EF, De Wever O, Del Portillo HA, Demaret T, Deville S, Devitt A, Dhondt B, Di Vizio D, Dieterich LC, Dolo V, Dominguez Rubio AP, Dominici M, Dourado MR, Driedonks TA, Duarte FV, Duncan HM, Eichenberger RM, Ekström K, El Andaloussi S, Elie-Caille C, Erdbrügger U, Falcón-Pérez JM, Fatima F, Fish JE, Flores-Bellver M, Försönits A, Frelet-Barrand A, Fricke F, Fuhrmann G, Gabrielsson S, Gámez-Valero A, Gardiner C, Gärtner K, Gaudin R, Gho YS, Giebel B, Gilbert C, Gimona M, Giusti I, Goberdhan DC, Görgens A, Gorski SM, Greening DW, Gross JC, Gualerzi A, Gupta GN, Gustafson D, Handberg A, Haraszti RA, Harrison P, Hegyesi H, Hendrix A, Hill AF, Hochberg FH, Hoffmann KF, Holder B, Holthofer H, Hosseinkhani B, Hu G, Huang Y, Huber V, Hunt S, Ibrahim AG, Ikezu T, Inal JM, Isin M, Ivanova A, Jackson HK, Jacobsen S, Jay SM, Jayachandran M, Jenster G, Jiang L, Johnson SM, Jones JC, Jong A, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Jung S, Kalluri R, Kano SI, Kaur S, Kawamura Y, Keller ET, Khamari D, Khomyakova E, Khvorova A, Kierulf P, Kim KP, Kislinger T, Klingeborn M, Klinke DJ 2nd, Kornek M, Kosanović MM, Kovács ÁF, Krämer-Albers EM, Krasemann S, Krause M, Kurochkin IV, Kusuma GD, Kuypers S, Laitinen S, Langevin SM, Languino LR, Lannigan J, Lässer C, Laurent LC, Lavieu G, Lázaro-Ibáñez E, Le Lay S, Lee MS, Lee YXF, Lemos DS, Lenassi M, Leszczynska A, Li IT, Liao K, Libregts SF, Ligeti E, Lim R, Lim SK, Linē A, Linnemannstöns K, Llorente A, Lombard CA, Lorenowicz MJ, Lörincz ÁM, Lötvall J, Lovett J, Lowry MC, Loyer X, Lu Q, Lukomska B, Lunavat TR, Maas SL, Malhi H, Marcilla A, Mariani J, Mariscal J, Martens-Uzunova ES, Martin-Jaular L, Martinez MC, Martins VR, Mathieu M, Mathivanan S, Maugeri M, McGinnis LK, McVey MJ, Meckes DG Jr, Meehan KL, Mertens I, Minciacchi VR, Möller A, Møller Jørgensen M, Morales-Kastresana A, Morhayim J, Mullier F, Muraca M, Musante L, Mussack V, Muth DC, Myburgh KH, Najrana T, Nawaz M, Nazarenko I, Nejsum P, Neri C, Neri T, Nieuwland R, Nimrichter L, Nolan JP, Nolte-'t Hoen EN, Noren Hooten N, O'Driscoll L, O'Grady T, O'Loghlen A, Ochiya T, Olivier M, Ortiz A, Ortiz LA, Osteikoetxea X, Østergaard O, Ostrowski M, Park J, Pegtel DM, Peinado H, Perut F, Pfaffl MW, Phinney DG, Pieters BC, Pink RC, Pisetsky DS, Pogge von Strandmann E, Polakovicova I, Poon IK, Powell BH, Prada I, Pulliam L, Quesenberry P, Radeghieri A, Raffai RL, Raimondo S, Rak J, Ramirez MI, Raposo G, Rayyan MS, Regev-Rudzki N, Ricklefs FL, Robbins PD, Roberts DD, Rodrigues SC, Rohde E, Rome S, Rouschop KM, Rughetti A, Russell AE, Saá P, Sahoo S, Salas-Huenuleo E, Sánchez C, Saugstad JA, Saul MJ, Schiffelers RM, Schneider R, Schøyen TH, Scott A, Shahaj E, Sharma S, Shatnyeva O, Shekari F, Shelke GV, Shetty AK, Shiba K, Siljander PR, Silva AM, Skowronek A, Snyder OL 2nd, Soares RP, Sódar BW, Soekmadji C, Sotillo J, Stahl PD, Stoorvogel W, Stott SL, Strasser EF, Swift S, Tahara H, Tewari M, Timms K, Tiwari S, Tixeira R, Tkach M, Toh WS, Tomasini R, Torrecilhas AC, Tosar JP, Toxavidis V, Urbanelli L, Vader P, van Balkom BW, van der Grein SG, Van Deun J, van Herwijnen MJ, Van Keuren-Jensen K, van Niel G, van Royen ME, van Wijnen AJ, Vasconcelos MH, Vechetti IJ Jr, Veit TD, Vella LJ, Velot É, Verweij FJ, Vestad B, Viñas JL, Visnovitz T, Vukman KV, Wahlgren J, Watson DC, Wauben MH, Weaver A, Webber JP, Weber V, Wehman AM, Weiss DJ, Welsh JA, Wendt S, Wheelock AM, Wiener Z, Witte L, Wolfram J, Xagorari A, Xander P, Xu J, Yan X, Yáñez-Mó M, Yin H, Yuana Y, Zappulli V, Zarubova J, Žėkas V, Zhang JY, Zhao Z, Zheng L, Zheutlin AR, Zickler AM, Zimmermann P, Zivkovic AM, Zocco D, Zuba-Surma EK. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7:1535750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6453] [Cited by in RCA: 7603] [Article Influence: 1086.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Arya SB, Collie SP, Parent CA. The ins-and-outs of exosome biogenesis, secretion, and internalization. Trends Cell Biol. 2024;34:90-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 141.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Théry C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:9-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1483] [Cited by in RCA: 2597] [Article Influence: 432.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:641-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3539] [Cited by in RCA: 3293] [Article Influence: 96.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bernardo ME, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:392-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 903] [Cited by in RCA: 1056] [Article Influence: 96.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Prockop DJ. Concise review: two negative feedback loops place mesenchymal stem/stromal cells at the center of early regulators of inflammation. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2042-2046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Samsonraj RM, Raghunath M, Nurcombe V, Hui JH, van Wijnen AJ, Cool SM. Concise Review: Multifaceted Characterization of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Use in Regenerative Medicine. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:2173-2185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 64.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Naji A, Eitoku M, Favier B, Deschaseaux F, Rouas-Freiss N, Suganuma N. Biological functions of mesenchymal stem cells and clinical implications. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76:3323-3348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 60.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ankrum JA, Ong JF, Karp JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: immune evasive, not immune privileged. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:252-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 872] [Cited by in RCA: 1124] [Article Influence: 102.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Al-Ghadban S, Bunnell BA. Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells: Immunomodulatory Effects and Therapeutic Potential. Physiology (Bethesda). 2020;35:125-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | de Castro LL, Lopes-Pacheco M, Weiss DJ, Cruz FF, Rocco PRM. Current understanding of the immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. J Mol Med (Berl). 2019;97:605-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shokri MR, Bozorgmehr M, Ghanavatinejad A, Falak R, Aleahmad M, Kazemnejad S, Shokri F, Zarnani AH. Human menstrual blood-derived stromal/stem cells modulate functional features of natural killer cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhu YG, Shi MM, Monsel A, Dai CX, Dong X, Shen H, Li SK, Chang J, Xu CL, Li P, Wang J, Shen MP, Ren CJ, Chen DC, Qu JM. Nebulized exosomes derived from allogenic adipose tissue mesenchymal stromal cells in patients with severe COVID-19: a pilot study. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liu Y, Li C, Wang S, Guo J, Guo J, Fu J, Ren L, An Y, He J, Li Z. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells confer potent immunosuppressive effects in Sjögren's syndrome by inducing regulatory T cells. Mod Rheumatol. 2021;31:186-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang Z, Yang C, Yan S, Sun J, Zhang J, Qu Z, Sun W, Zang J, Xu D. Emerging Role and Mechanism of Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Rheumatic Disease. J Inflamm Res. 2024;17:6827-6846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Harrell CR, Jovicic N, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles as New Remedies in the Therapy of Inflammatory Diseases. Cells. 2019;8:1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 87.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ala M. The beneficial effects of mesenchymal stem cells and their exosomes on myocardial infarction and critical considerations for enhancing their efficacy. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;89:101980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Giovannelli L, Bari E, Jommi C, Tartara F, Armocida D, Garbossa D, Cofano F, Torre ML, Segale L. Mesenchymal stem cell secretome and extracellular vesicles for neurodegenerative diseases: Risk-benefit profile and next steps for the market access. Bioact Mater. 2023;29:16-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yu H, Wang Z. Cardiomyocyte-Derived Exosomes: Biological Functions and Potential Therapeutic Implications. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cao Q, Huang C, Chen XM, Pollock CA. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies in Chronic Kidney Disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:816656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bian D, Wu Y, Song G, Azizi R, Zamani A. The application of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and their derivative exosome in skin wound healing: a comprehensive review. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 62.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fujii S, Miura Y. Immunomodulatory and Regenerative Effects of MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles to Treat Acute GVHD. Stem Cells. 2022;40:977-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Qiu G, Zheng G, Ge M, Wang J, Huang R, Shu Q, Xu J. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles affect disease outcomes via transfer of microRNAs. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhang H, Wang L, Li C, Yu Y, Yi Y, Wang J, Chen D. Exosome-Induced Regulation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Arabpour M, Saghazadeh A, Rezaei N. Anti-inflammatory and M2 macrophage polarization-promoting effect of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;97:107823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 67.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ocansey DKW, Zhang L, Wang Y, Yan Y, Qian H, Zhang X, Xu W, Mao F. Exosome-mediated effects and applications in inflammatory bowel disease. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2020;95:1287-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shen Z, Huang W, Liu J, Tian J, Wang S, Rui K. Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes on Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;12:749192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lin Z, Wu Y, Xu Y, Li G, Li Z, Liu T. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in cancer therapy resistance: recent advances and therapeutic potential. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Skotland T, Hessvik NP, Sandvig K, Llorente A. Exosomal lipid composition and the role of ether lipids and phosphoinositides in exosome biology. J Lipid Res. 2019;60:9-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 69.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pascual M, Ibáñez F, Guerri C. Exosomes as mediators of neuron-glia communication in neuroinflammation. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15:796-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yin T, Xin H, Yu J, Teng F. The role of exosomes in tumour immunity under radiotherapy: eliciting abscopal effects? Biomark Res. 2021;9:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Franco da Cunha F, Andrade-Oliveira V, Candido de Almeida D, Borges da Silva T, Naffah de Souza Breda C, Costa Cruz M, Faquim-Mauro EL, Antonio Cenedeze M, Ioshie Hiyane M, Pacheco-Silva A, Aparecida Cavinato R, Torrecilhas AC, Olsen Saraiva Câmara N. Extracellular Vesicles isolated from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Modulate CD4(+) T Lymphocytes Toward a Regulatory Profile. Cells. 2020;9:1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ou Q, Dou X, Tang J, Wu P, Pan D. Small extracellular vesicles derived from PD-L1-modified mesenchymal stem cell promote Tregs differentiation and prolong allograft survival. Cell Tissue Res. 2022;389:465-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lotfy A, AboQuella NM, Wang H. Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in clinical trials. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zheng G, Huang R, Qiu G, Ge M, Wang J, Shu Q, Xu J. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles: regenerative and immunomodulatory effects and potential applications in sepsis. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;374:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Qiu G, Zheng G, Ge M, Wang J, Huang R, Shu Q, Xu J. Functional proteins of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Keshtkar S, Azarpira N, Ghahremani MH. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: novel frontiers in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 87.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Lai RC, Arslan F, Lee MM, Sze NS, Choo A, Chen TS, Salto-Tellez M, Timmers L, Lee CN, El Oakley RM, Pasterkamp G, de Kleijn DP, Lim SK. Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2010;4:214-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1435] [Cited by in RCA: 1675] [Article Influence: 111.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Bruno S, Tapparo M, Collino F, Chiabotto G, Deregibus MC, Soares Lindoso R, Neri F, Kholia S, Giunti S, Wen S, Quesenberry P, Camussi G. Renal Regenerative Potential of Different Extracellular Vesicle Populations Derived from Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017;23:1262-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Yu B, Kim HW, Gong M, Wang J, Millard RW, Wang Y, Ashraf M, Xu M. Exosomes secreted from GATA-4 overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells serve as a reservoir of anti-apoptotic microRNAs for cardioprotection. Int J Cardiol. 2015;182:349-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kim YG, Choi J, Kim K. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes for Effective Cartilage Tissue Repair and Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Biotechnol J. 2020;15:e2000082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Rezaie J, Rahbarghazi R, Pezeshki M, Mazhar M, Yekani F, Khaksar M, Shokrollahi E, Amini H, Hashemzadeh S, Sokullu SE, Tokac M. Cardioprotective role of extracellular vesicles: A highlight on exosome beneficial effects in cardiovascular diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:21732-21745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Tan F, Li X, Wang Z, Li J, Shahzad K, Zheng J. Clinical applications of stem cell-derived exosomes. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Yang D, Zhang W, Zhang H, Zhang F, Chen L, Ma L, Larcher LM, Chen S, Liu N, Zhao Q, Tran PHL, Chen C, Veedu RN, Wang T. Progress, opportunity, and perspective on exosome isolation - efforts for efficient exosome-based theranostics. Theranostics. 2020;10:3684-3707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 707] [Cited by in RCA: 656] [Article Influence: 131.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Wang S, Lei B, Zhang E, Gong P, Gu J, He L, Han L, Yuan Z. Targeted Therapy for Inflammatory Diseases with Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Derived Exosomes: From Basic to Clinics. Int J Nanomedicine. 2022;17:1757-1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Yan L, Li J, Zhang C. The role of MSCs and CAR-MSCs in cellular immunotherapy. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21:187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Zhao Y, Zhong X, Du F, Wu X, Li M, Wen Q, Shen J, Chen Y, Zhang X, Yang Z, Deng Y, Liu X, Zou C, Du Y, Xiao Z. The Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cancer Immunotherapy. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;18:1056-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Ong HS, Riau AK, Yam GH, Yusoff NZBM, Han EJY, Goh TW, Lai RC, Lim SK, Mehta JS. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes as Immunomodulatory Therapy for Corneal Scarring. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:7456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Fujii S, Miura Y, Fujishiro A, Shindo T, Shimazu Y, Hirai H, Tahara H, Takaori-Kondo A, Ichinohe T, Maekawa T. Graft-Versus-Host Disease Amelioration by Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Is Associated with Peripheral Preservation of Naive T Cell Populations. Stem Cells. 2018;36:434-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Zhao S, Mi Y, Guan B, Zheng B, Wei P, Gu Y, Zhang Z, Cai S, Xu Y, Li X, He X, Zhong X, Li G, Chen Z, Li D. Tumor-derived exosomal miR-934 induces macrophage M2 polarization to promote liver metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 524] [Article Influence: 104.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Zhao J, Li X, Hu J, Chen F, Qiao S, Sun X, Gao L, Xie J, Xu B. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes attenuate myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury through miR-182-regulated macrophage polarization. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115:1205-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 543] [Article Influence: 108.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Jiao Y, Zhang T, Zhang C, Ji H, Tong X, Xia R, Wang W, Ma Z, Shi X. Exosomal miR-30d-5p of neutrophils induces M1 macrophage polarization and primes macrophage pyroptosis in sepsis-related acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2021;25:356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 82.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Xu H, Nie X, Deng W, Zhou H, Huang D, Wang Z. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes ameliorate LPS-induced acute lung injury by miR-223-regulated alveolar macrophage M2 polarization. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2024;38:e23568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Gunassekaran GR, Poongkavithai Vadevoo SM, Baek MC, Lee B. M1 macrophage exosomes engineered to foster M1 polarization and target the IL-4 receptor inhibit tumor growth by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages into M1-like macrophages. Biomaterials. 2021;278:121137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 72.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Ou X, Wang H, Tie H, Liao J, Luo Y, Huang W, Yu R, Song L, Zhu J. Novel plant-derived exosome-like nanovesicles from Catharanthus roseus: preparation, characterization, and immunostimulatory effect via TNF-α/NF-κB/PU.1 axis. J Nanobiotechnology. 2023;21:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Li C, Guo F, Wang X, Liu D, Wu B, Wang F, Chen W. Exosome-based targeted RNA delivery for immune tolerance induction in skin transplantation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2020;108:1493-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Mendt M, Rezvani K, Shpall E. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes for clinical use. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54:789-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 69.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Jahangiri B, Khalaj-Kondori M, Asadollahi E, Kian Saei A, Sadeghizadeh M. Dual impacts of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes on cancer cells: unravelling complex interactions. J Cell Commun Signal. 2023;17:1229-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Oveili E, Vafaei S, Bazavar H, Eslami Y, Mamaghanizadeh E, Yasamineh S, Gholizadeh O. The potential use of mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes as microRNAs delivery systems in different diseases. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Riazifar M, Mohammadi MR, Pone EJ, Yeri A, Lässer C, Segaliny AI, McIntyre LL, Shelke GV, Hutchins E, Hamamoto A, Calle EN, Crescitelli R, Liao W, Pham V, Yin Y, Jayaraman J, Lakey JRT, Walsh CM, Van Keuren-Jensen K, Lotvall J, Zhao W. Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes as Nanotherapeutics for Autoimmune and Neurodegenerative Disorders. ACS Nano. 2019;13:6670-6688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 68.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Naaldijk Y, Sherman LS, Turrini N, Kenfack Y, Ratajczak MZ, Souayah N, Rameshwar P, Ulrich H. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Macrophage Crosstalk Provides Specific Exosomal Cargo to Direct Immune Response Licensing of Macrophages during Inflammatory Responses. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2024;20:218-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Wang S, Huo J, Liu Y, Chen L, Ren X, Li X, Wang M, Jin P, Huang J, Nie N, Zhang J, Shao Y, Ge M, Zheng Y. Impaired immunosuppressive effect of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes on T cells in aplastic anemia. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14:285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Liu W, Li L, Rong Y, Qian D, Chen J, Zhou Z, Luo Y, Jiang D, Cheng L, Zhao S, Kong F, Wang J, Zhou Z, Xu T, Gong F, Huang Y, Gu C, Zhao X, Bai J, Wang F, Zhao W, Zhang L, Li X, Yin G, Fan J, Cai W. Hypoxic mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote bone fracture healing by the transfer of miR-126. Acta Biomater. 2020;103:196-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 56.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Zhang S, Chuah SJ, Lai RC, Hui JHP, Lim SK, Toh WS. MSC exosomes mediate cartilage repair by enhancing proliferation, attenuating apoptosis and modulating immune reactivity. Biomaterials. 2018;156:16-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 646] [Article Influence: 92.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Qiu W, Guo Q, Guo X, Wang C, Li B, Qi Y, Wang S, Zhao R, Han X, Du H, Zhao S, Pan Z, Fan Y, Wang Q, Gao Z, Li G, Xue H. Mesenchymal stem cells, as glioma exosomal immunosuppressive signal multipliers, enhance MDSCs immunosuppressive activity through the miR-21/SP1/DNMT1 positive feedback loop. J Nanobiotechnology. 2023;21:233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zhang S, Teo KYW, Chuah SJ, Lai RC, Lim SK, Toh WS. MSC exosomes alleviate temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis by attenuating inflammation and restoring matrix homeostasis. Biomaterials. 2019;200:35-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 65.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Del Papa B, Sportoletti P, Cecchini D, Rosati E, Balucani C, Baldoni S, Fettucciari K, Marconi P, Martelli MF, Falzetti F, Di Ianni M. Notch1 modulates mesenchymal stem cells mediated regulatory T-cell induction. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:182-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Kim JY, Park M, Kim YH, Ryu KH, Lee KH, Cho KA, Woo SY. Tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells (T-MSCs) prevent Th17-mediated autoimmune response via regulation of the programmed death-1/programmed death ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) pathway. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:e1022-e1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Bansal S, Rahman M, Ravichandran R, Canez J, Fleming T, Mohanakumar T. Extracellular Vesicles in Transplantation: Friend or Foe. Transplantation. 2024;108:374-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Lee SH, Kwon JE, Cho ML. Immunological pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Intest Res. 2018;16:26-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 55.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Cao L, Xu H, Wang G, Liu M, Tian D, Yuan Z. Extracellular vesicles derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attenuate dextran sodium sulfate-induced ulcerative colitis by promoting M2 macrophage polarization. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;72:264-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Yang J, Liu XX, Fan H, Tang Q, Shou ZX, Zuo DM, Zou Z, Xu M, Chen QY, Peng Y, Deng SJ, Liu YJ. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Protect against Experimental Colitis via Attenuating Colon Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Gazdic M, Simovic Markovic B, Vucicevic L, Nikolic T, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, Trajkovic V, Lukic ML, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal stem cells protect from acute liver injury by attenuating hepatotoxicity of liver natural killer T cells in an inducible nitric oxide synthase- and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-dependent manner. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:e1173-e1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Chen L, Lu FB, Chen DZ, Wu JL, Hu ED, Xu LM, Zheng MH, Li H, Huang Y, Jin XY, Gong YW, Lin Z, Wang XD, Chen YP. BMSCs-derived miR-223-containing exosomes contribute to liver protection in experimental autoimmune hepatitis. Mol Immunol. 2018;93:38-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Li JW, Wei L, Han Z, Chen Z. Mesenchymal stromal cells-derived exosomes alleviate ischemia/reperfusion injury in mouse lung by transporting anti-apoptotic miR-21-5p. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;852:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Mansouri N, Willis GR, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Reis M, Nassiri S, Mitsialis SA, Kourembanas S. Mesenchymal stromal cell exosomes prevent and revert experimental pulmonary fibrosis through modulation of monocyte phenotypes. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e128060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Shiue SJ, Rau RH, Shiue HS, Hung YW, Li ZX, Yang KD, Cheng JK. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes as a cell-free therapy for nerve injury-induced pain in rats. Pain. 2019;160:210-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Li J, Pan Y, Yang J, Wang J, Jiang Q, Dou H, Hou Y. Tumor necrosis factor-α-primed mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote M2 macrophage polarization via Galectin-1 and modify intrauterine adhesion on a novel murine model. Front Immunol. 2022;13:945234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Saadh MJ, K Abdulsahib W, Ashurova D, Sanghvi G, Ballal S, Sharma R, Kumar Pathak P, Aman S, Kumar A, Feez Sead F, Chaitanya MVNL. FLT3-mutated AML: immune evasion through exosome-mediated mechanisms and innovative combination therapies targeting immune escape. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2025;25:143-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Lee YJ, Shin KJ, Jang HJ, Ryu JS, Lee CY, Yoon JH, Seo JK, Park S, Lee S, Je AR, Huh YH, Kong SY, Kwon T, Suh PG, Chae YC. GPR143 controls ESCRT-dependent exosome biogenesis and promotes cancer metastasis. Dev Cell. 2023;58:320-334.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Harrell CR, Volarevic A, Djonov VG, Jovicic N, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal Stem Cell: A Friend or Foe in Anti-Tumor Immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:12429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Biswas S, Mandal G, Roy Chowdhury S, Purohit S, Payne KK, Anadon C, Gupta A, Swanson P, Yu X, Conejo-Garcia JR, Bhattacharyya A. Exosomes Produced by Mesenchymal Stem Cells Drive Differentiation of Myeloid Cells into Immunosuppressive M2-Polarized Macrophages in Breast Cancer. J Immunol. 2019;203:3447-3460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Börger V, Bremer M, Ferrer-Tur R, Gockeln L, Stambouli O, Becic A, Giebel B. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Their Potential as Novel Immunomodulatory Therapeutic Agents. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |